Abstract

Ischemia and reperfusion injury is an inevitable event in renal transplantation. The most important consequences are delayed graft function, longer length of stay, higher hospital costs, high risk of acute rejection, and negative impact of long-term follow-up. Currently, many factors are involved in their pathophysiology and could be classified into two different paradigms for education purposes: hemodynamic and immune. The hemodynamic paradigm is described as the reduction of oxygen delivery due to blood flow interruption, involving many hormone systems, and oxygen-free radicals produced after reperfusion. The immune paradigm has been recently described and involves immune system cells, especially T cells, with a central role in this injury. According to these concepts, new strategies to prevent ischemia and reperfusion injury have been studied, particularly the more physiological forms of storing the kidney, such as the pump machine and the use of antilymphocyte antibody therapy before reperfusion. Pump machine perfusion reduces delayed graft function prevalence and length of stay at hospital, and increases long-term graft survival. The use of antilymphocyte antibody therapy before reperfusion, such as Thymoglobulin™, can reduce the prevalence of delayed graft function and chronic graft dysfunction.

Keywords: Reperfusion injury, Ischemia, Delayed graft function, Graft rejection, Perfusion/utilization

INTRODUCTION

Acute kidney injury (AKI) of ischemic nature is the most common form of intrinsic renal disease in adults, and is associated with adverse clinical outcomes and high mortality rates.(1) The incidence of AKI in hospitalized patients varies from 2 to 7%, and can be higher than 10% in patients at intensive care units.(2) Currently, the mortality of AKI patients in native kidneys is approximately 50%, ranging from 30 to 70%.(3,4) In terms of pathophysiology, renal tubular ischemic disease was considered as resulting from tissue hypoxia.(5) hen observing that glomerular filtration would not start immediately after reestablishing oxygen supply to the damaged tissue, some studies demonstrated two important concepts. First, that reperfusion after ischemia was part of the pathophysiology of the lesion, by means of generation of free oxygen species, with modifications in the cell environment of the renal tubule. Second, that a determined time interval was necessary for recovery of the tubular structure.(1,5,6) In this way, the ischemia and reperfusion injury (IRI) became the central pathophysiologic mechanism of ischemic AKI, with the participation of various hormone systems.(5,6)

However knowledge about of the pathophysiology of IRI enhanced during the last decade, identifying components of the immune system as mediators of the lesion.(7-11) Thus, hypoxia is the initial insult and trigger of IRI, but the approach of a new paradigm for this lesion involves immune system cells, especially T cells and activation and cell adhesion molecules, that is, the immune paradigm. Despite not being frequent in native kidneys, IRI is an inevitable event in solid organ transplants. The relation between mortality and IRI is well established in native kidneys, but it is not clear in kidney transplantation. It is not possible to affirm that IRI is a factor independent from mortality in this mode of treatment, although it is related to increased risk of acute rejection (AR) and loss of renal graft in the long run. Therefore, some considerations about IRI in kidney transplant will be presented.

HEMODYNAMIC PARADIGM

The hemodynamic paradigm of IRI in organ transplants stems from the principle that the central factors involved in IRI are the imbalance between offer and consumption of oxygen in the graft, which involves management of the donor, especially the donor with encephalic death; the variables related to the removal of the organ; the manner of preservation; the time during which the organ remains without blood circulation; and the effects of reperfusion. The clinical results with kidney transplantation can be influenced by the prolonged storage of the organ, which is correlated with the initial delay in graft function, complications with managing immunosuppression and length of hospital stay, among other outcomes.(6)

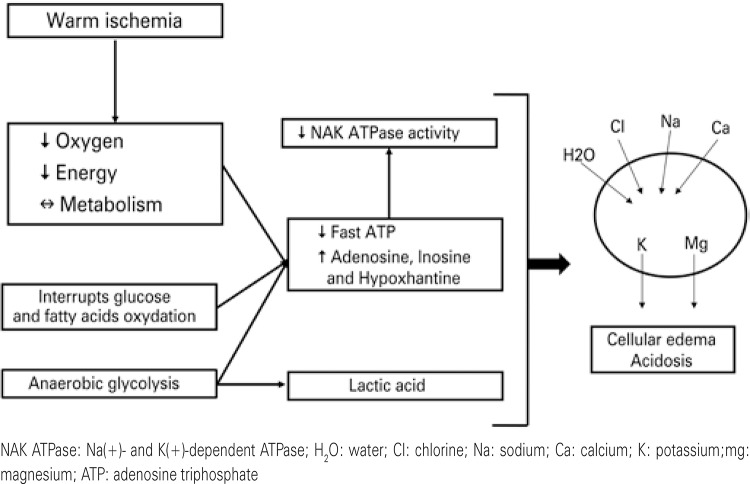

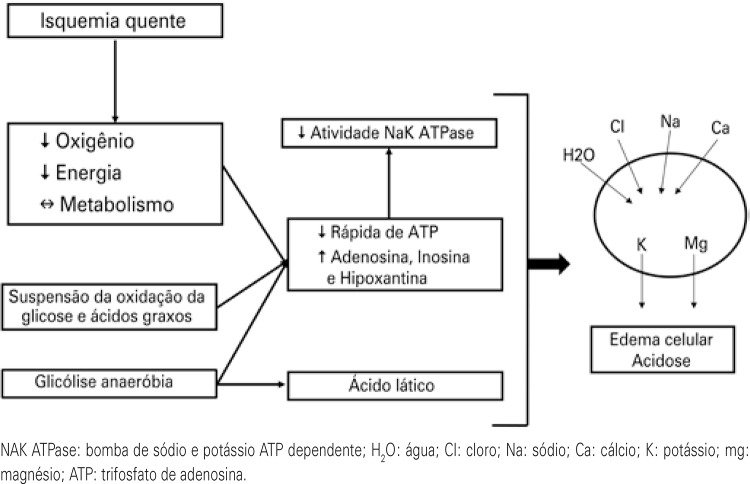

Between the removal of the dead donor organ until reperfusion in the receptor, the renal tissue is exposed to two different processes: warm ischemia and cold ischemia. The time of warm ischemia is defined by the period between clamping of the donor’s artery until perfusion with the preservation solution. This is the period in which cell damage is more evident. During warm ischemia, there is an abrupt interruption of the oxygen supply to the cells, with a consequent reduction of aerobic metabolism, suspension of glucose and fatty acid oxidation, and transfer of glycolysis to the anaerobic route, which significantly reduces the quantity of intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (Figure 1). With little ATP available, there is reduction of Na/K/ATPase activity, with a hydroelectrolyte imbalance between the intra- and extracellular space, favoring the formation of cellular edema. Additionally, the anaerobic metabolism substantially increases the quantity of lactic acid, causing a drop in intracellular pH. Studies show that kidneys exposed to more than one hour of warm ischemia become unviable, and when for more than five minutes, they are already associated with unfavorable outcomes of IRI.(1,6) The period corresponding to the graft perfusion until unclamping of the anastomosis in the receptor is the of cold ischemia time (CIT).

Figure 1. Impact of warm ischemia on the intracellular environment.

IMMUNE PARADIGM

There are at least five lines of evidence demonstrating the participation of T-lymphocytes and of their surface molecules in the lesion: (1) lymphocytes are found in tissues after ischemia;(10,11) (2) cytokines classically produced by these cells are amply expressed in tissue (upregulation) after the lesion;(12,13) (3) molecules such as CD11/CD18 and ICAM-1, responsible for leucocyte adhesion, are mediators of experimental IRI;(13-15) (4) the lymphocyte is the mediator of IRI in murine livers;(16) (5) blockage of lymphocyte costimulation routes, such as CD28-CD80, via CTLA4, significantly reduces the impacts of the lesion in experimental models.(17)

Corroborating this evidence, an elegant experiment performed in knockout mice for T CD4+/CD8+ cells demonstrated that, in the absence of the CD4+ phenotype, IRI was dramatically attenuated.(18) The proposed activation mechanisms of T-lymphocytes in IRI, on the other hand, follow three lines of evidence: (1) activation of the T-lymphocyte I an independent alloantigen manner; (2) mobilization of the T-lymphocyte from the circulation to the lesion site, by means of transendothelial migration; and (3) aggression to the target tissue of the initial insult.

It is speculated that the reactive species of oxygen could modify the structure of their own molecules, making them become antigens.(19) After reaching the lesion site, the role played by the lymphocyte is not known. Lai et al., however, demonstrated that the infiltration of T cells occurs in the first hour after the injury, remaining in the tissue for about 4 hours and leaving the tissue free after 24 hours, a model that has been called hit-and-run.(11)

CLINICAL ASPECTS

Clinically, IRI in kidney transplant is manifested as the delayed graft function (DGF), despite there not being a consensus for its clinical definition. In a study that analyzed 65 publications between 1984 and 2004, which covered the definition of DGF, the authors identified 18 different definitions based on two criteria: need for dialysis after transplant or the non-occurrence of creatinine reduction. However, the objective parameters, such as time of dialysis after the transplant or rate of creatinine reduction vary significantly (Table 1).(20) This absence of standardization in concepts has made it difficult to establish precise data, such as prevalence and its impact on short- and long-term outcomes.

Table 1. Different definitions used for delayed graft function.

| Definitions | Studies | Patients |

|---|---|---|

| Definitions based on dialysis | ||

| Need for dialysis in the first week after transplant | 41 | 259,251 |

| Need for dialysis in the first week after transplant, as long as the hyperacute rejection and vascular or urological complications are ruled out | 2 | 760 |

| Need for dialysis after transplant | 2 | 737 |

| Need for dialysis in the first 10 days after transplant | 1 | 41 |

| Absence of any type of renal function that might impose the need for 2 or more dialyses in the first week after transplant | 1 | 547 |

| Need for dialysis in the first week after transplant, having excluded a single dialysis immediately after transplant, if it was indicated for hyperkalemia | 1 | 319 |

| Return to maintenance dialysis in the first 4 days after transplant | 1 | 263 |

| Definitions based on creatinine | ||

| Increase in creatinine or reduction <10% in the 3 consecutive days after transplant | 5 | 1471 |

| Reduction in creatinine <30% and/or urinary creatinine <1,000mg on the second day of transplant | 2 | 401 |

| Creatinine >2.5mg/dL on the seventh day after transplant | 1 | 99 |

| Time necessary for clearance of creatinine to be >10mL/min superior to 1 week | 1 | 843 |

| Non-reduction of creatinine in the first 48 hours, in the absence of rejection | 1 | 291 |

| Combination | ||

| Non-reduction of serum creatinine at levels inferior to those pre-transplant, even with an adequate urinary volume | 1 | 158 |

| Increase in creatinine in the first 6-8 hours after the transplant or urinary volume <300 mL, despite adequate volemia and use of diuretics | 1 | 143 |

| Dialysis after transplant or creatinine >150 mcmol/L 8 days after the transplant | 1 | 112 |

| Urinary volume <1.0 L in 24 hours and <25% of reduction in creatinine in the first 24 hours after transplant | 1 | 244 |

| Urinary volume <75 mL/hour in the first 48 hours or non-reduction in creatinine >10% in the first 48 hours | 1 | 66 |

| Need for dialysis in the first week after transplant or non-reduction in creatinine in the first 24 hours after transplant | 1 | 104 |

DGF is the most common complication in the immediate post-transplant period with a deceased donor, and it affects 8 to 50% of this type of transplant in the United States; in Brazil, it reaches 80%.(21,22) In a study conducted by our group with patients transplanted with deceased kidney donors at the Hospital Israelita Albert Einstein and Universidade Federal de São Paulo, between 2000 and 2005, we observed a 58.6% prevalence of DGF. When we compared these patients to those who also received grafts from dead donors, but who had immediate function, we noted that patients with more than 50 months on dialysis before the transplant had a risk of DGF 42% greater than those with less time on dialysis, and that a CIT superior to 24 hours increased this risk by 57%.(23) Despite the time or warm ischemia being more damaging to the organ, currently, with skilled teams, this time rarely exceeds 5 minutes, and CIT is one of the primary variables related to DGF.(21-24) There is an increase in incidence of DGF of about 8% for each 6-hour increase in CIT.(23) Other factors, such as HLA (human leukocyte antigen) compatibility, donor with expanded criterion (or isolated age of the donor), race and gender of the receptor, have also been implicated in the association with intensity of the IRI after kidney transplant.(21,23-25)

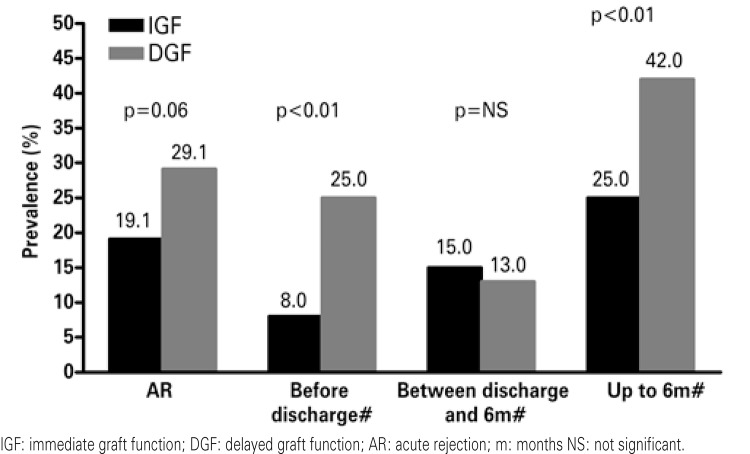

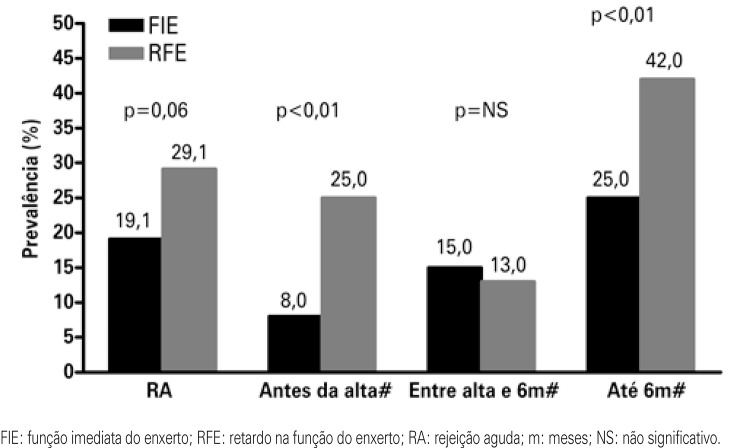

DGF causes prolonged hospitalization, increased costs and greater complexity in management of immunosuppressing drugs.(26-29) The longer length of stay add approximately US$ 25,000 per patient to the transplant cost.(29) Another immediate consequence is the difficulty in initial management of immunosuppressing agents, especially the calcineurin inhibitors and mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin).(30) It is also speculated that DGF is associated with the risk of AR, as well as chronic graft dysfucntion (CGD). Some studies showed a correlation of prevalence between DGF and AR, in which the risk of AR may be duplicated in patients that present with DGF.(21-23,24). Figure 2 shows the associations between DGF and AR, according to time of transplant. On the left bar the incidences of AR are shown as per DGF or immediate graft function among 628 patients transplanted in the city of São Paulo (SP).(23) On the other bars (demonstrated with the symbol # on figure 2), the incidences of AR between the transplant and hospital discharge, between discharge and 6 months after transplant, and the episodes of AR that occurred after the hospital discharge and up to 6 months after the transplant are shown.(21)

Figure 2. Correlation of prevalence between delayed graft function and acute rejection.

When the long-term outcomes are evaluated, such as CGD or graft survival, it is debatable as to whether DGF, alone, would have a negative impact or if the impact would be caused by the effect of the AR or of the two superimposed variables. We evaluated the influence of DGF in the kidney function of patients transplanted with a deceased donor and observed worse function, by means of creatinine clearance measures, for up to two years of follow-up.(23) It is still not yet clear if this difference in function, however, can compromise the survival of the graft. Troppman et al.(31) observed that DGF, in the absence of AR, had no influence on the clinical outcomes. Ojo et al.,(21) however, observed a 14% reduction in graft survival one year after transplant in patients with DGF who did not have AR.

STRATEGIES TO ATTENUATE THE EFFECTS OF ISCHEMIA AND REPERFUSION INJURY

From the hemodynamic point of view, adequate care with the donor, especially to avoid hemodynamic instability and need for large quantities of vasoactive drugs, avoid large electrolytic variations and reduce the CIT, are effective strategies in reducing the prevalence of IRI. Still as strategies of better hemodynamics, the adequate preservation of the organ has a positive impact. With the objective of attenuating the negative impact of the cellular effects of oxygen privation (Figure 1), preservation solutions and organ cooling are used. The preservation solutions try to mimic the electrolytic and osmotic intracellular environment, with the objective of stabilizing the plasma membrane, avoid edema, and reduce as much as possible the cell damage caused by ischemia and acidosis.(32) Additionally, the kidneys to be implanted are presented at temperatures as low as 4ºC, which reduces the metabolism rates by 90 to 95% and with this, decreases the consumption of ATP and the deviation of the metabolism to anaerobic routs.(1,24,32)

Two strategies of preservation solution perfusion may be used: static, in which the kidney is preserved with hypothermic solution and stored in a thermal protection recipient, or the continuous mechanical perfusion which, besides using the hypothermic preservation solution, maintains the pulsatile flow of this solution circulating in the graft, mimicking blood flow circulation.(33,34) Mechanical perfusion seem to be associated with the reduction of negative impacts on IRI. In a study conducted by Moers et al., 672 kidneys of 336 deceased donors were paired 1:1 for two different types of perfusion.(33) There was a reduction in the prevalence of DGF (30.1% to 22.9%; p=0.03), primary absence of the graft function (4.8% to 2.1%; p=0.08), and of the time in DGF (13 to 10 days; p=0,04), that is, the results were favorable to mechanical perfusion. In a multivariate analysis, the use of this strategy reduced by 43% the risk of DGF. At the end of one-year follow-up (94% versus 90%; p=0.04) and of 3 years (91% versus 87%; p=0.04), graft survival was significantly better in the patients who received kidneys from mechanical perfusion.(33,34)

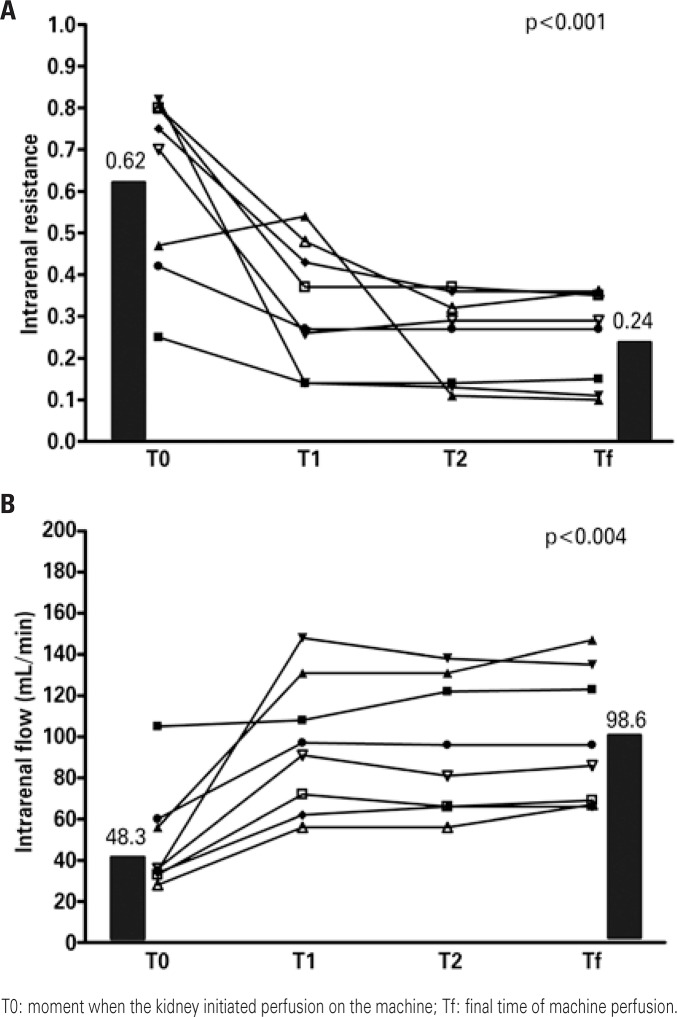

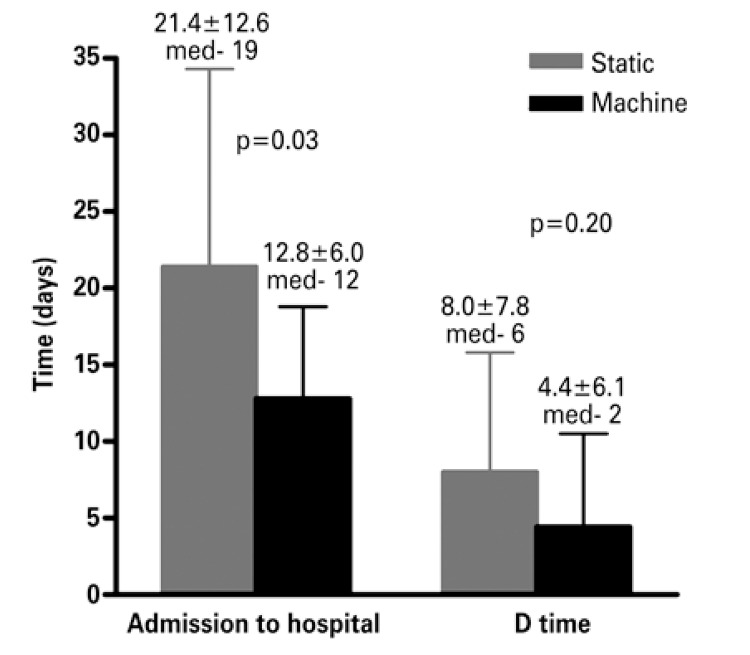

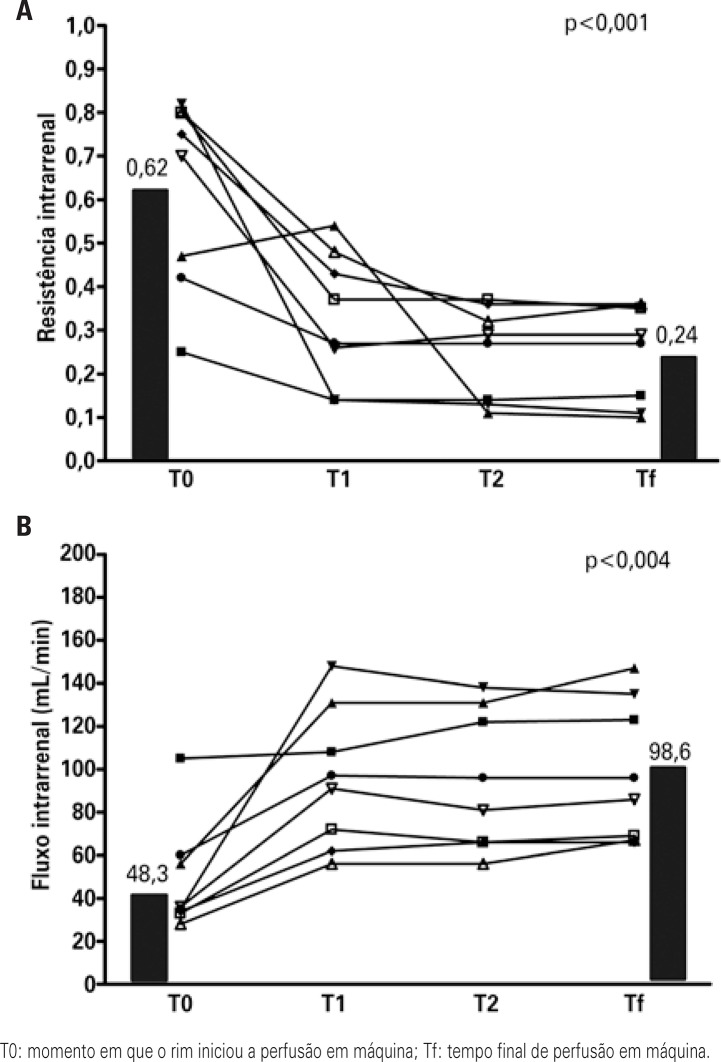

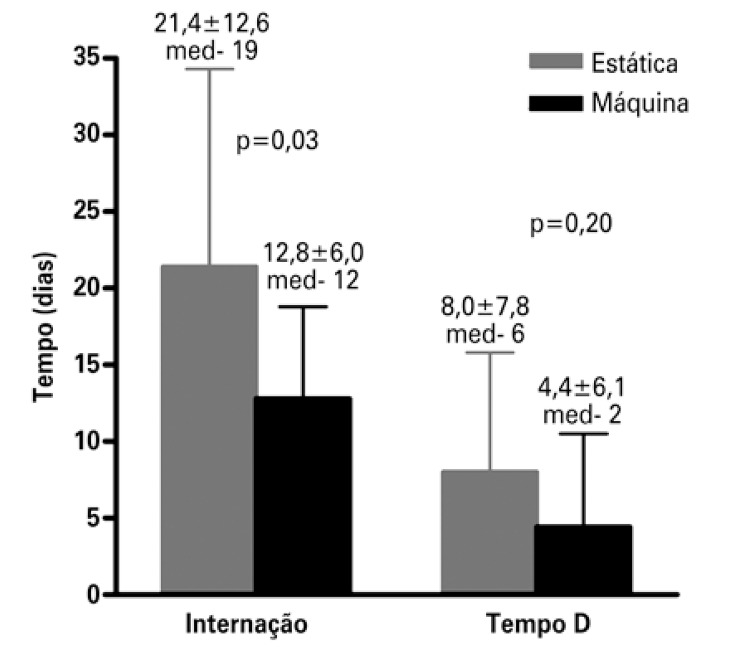

In Brazil, the prevention strategy used on a large scale is static perfusion. Recently, our group began to use a mixed strategy: we received the kidneys in static perfusion, which is the form in which they are distributed by the transplant center, and we maintained the kidney in pulsatile mechanical preservation until the time of surgery. The rationale for placing the kidney in the machine even after the static perfusion is that, within the hemodynamic paradigm, we observe regional alterations in blood flow, which can be confirmed by the increased intrarenal vascular resistance, with resulting reduction of plasma flow.(35) Analysis of the first transplants performed with this mixed strategy (placing the kidney in the machine after static perfusion) demonstrated a significant reduction in intrarenal resistance during the first 6 hours of mechanical perfusion (Figure 3A), and consequently presenting a significant increase in the intrarenal flow (Figure 3B). In both figures, T0 was the moment in which the kidney initiated machine perfusion, that is, the end of the CIT in static perfusion and Tf was the final time of machine perfusion. The time between T0 and Tf among these patients was 9.3 hours. We noted no reduction in prevalence of DGF, but in the first cases evaluated there was significant reduction in dialysis duration after the transplant, with consequent reduction in length of hospital stay (Figure 4). We noted a reduction in hospital stay from 21.4±12.6 days to 12.8±6.0 days (p=0.03), as well as a trend to reduced dialysis time from 8.0±7.8 days to 4.4±6.1 days (p=0.20).

Figure 3. Intrarenal hemodynamics after the use of perfusion machine.

Figure 4. Length of hospital stay and dialysis time (D time) after transplant with the perfusion machine.

Within the context of the immune paradigm, a series of studies, both experimental and clinical, demonstrated the benefit of using drugs that deplete leukocytes or antibodies directed against adhesion molecules, attenuating the effects of the IRI. Based on these concepts, Yokota et al., in an experimental study, demonstrated that the use of antibodies that deplete T CD4+ cells in mice attenuated IRI, and that this effect was potentiated by performing thymectomy prior to the lesion.(36) Since knowledge evolved on the primary mechanisms of action of the ALA antilymphocyte antibodies, especially in lymphocytic depletion and as T cell modulators, in parallel with the growing knowledge of the role of T cells in IRI, there has been interest in evaluating the benefit of these antibodies. The polyclonal antithymocyte antibody (ATG) is the most studied polyclonal antibody and has the characteristics of rapid action, antigen specificity, with consequent depletion and modulation of the immune response. The benefits of use of ATG in IRI would be supported by the reduction of the mass of circulating lymphocytes and by the blockage of the machinery necessary for the migration of the lymphocyte to the lesion site.(37)

Beiras-Fernandez et al., using a model of IRI in non-human primates, demonstrated that the use of ATG significantly reduced the infiltration of leukocytes in connective tissue, vessels, perivascular tissue, and muscle itself.(38) These findings were translated into lower lesion scores, with lower rates of necrosis, hemorrhage areas, and areas of diffuse infiltration, both in muscle tissue and in connective tissue of animals that used the drug. All these concepts gave support to the use of ATG with the objective of reducing the effects of IRI. Goggins et al. confirmed this hypothesis demonstrating that the use of the dose previous to unclamping the vascular anastomosis significantly reduced the occurrence of DGF (14.8% versus 35.5%), even though these results were not reproduced in other studies.(39) We compared two cohorts of paired patients, in which one received induction with Thymoglobulin® and the other, not, and we noted no reduction in the prevalence of DGF.(40)

CONCLUSION

The ischemia and reperfusion injury in kidney transplantation is currently understood in light of two different paradigms: hemodynamic and immune. In addition to the classic privation of circulation, with reduction of aerobic activity and of the lesion caused by the oxygen-free radicals in reperfusion and in involvement of hormone systems, the involvement of the immune system in the genesis of ischemia and reperfusion injury has been discussed, especially the central role of T cells and its surface molecules. The adequate management of donors, reduction in warm and cold ischemia time, and the more physiological strategies of storage of the kidneys are related to smaller impact of the ischemia and reperfusion injury in the evolution of kidney transplant. Likewise, the immune system block by means of activated T cell deprivation, as well as the neutralization of the surface molecules of these cells, with the use of polyclonal antibodies that deplete lymphocytes, may have a protective role on the grafts. This is still a field for further investigation on exploration to improve the short- and long-term outcomes, especially in kidney transplant of a deceased donor.

REFERENCES

- 1.Molitoris BA. Ischemic acute renal failure: exciting times at our fingertips. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1998;7(4):405–406. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199807000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waikar SS, Liu KD, Chertow GM. Diagnosis, epidemiology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3(3):844–861. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05191107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu CY, Chertow GM, McCulloch CE, Fan D, Ordoñez JD, Go AS. Nonrecovery of kidney function and death after acute on chronic renal failure. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(5):891–898. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05571008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipakmg, Garg AX, Parikh CR. Long-term risk of mortality and other adverse outcomes after acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53(6):961–973. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.11.034. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brady H, Singer GG. Acute renal failure. Lancet. 1995;346(8989):1533–1540. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92057-9. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tilney NL, Guttmann RD. Effects of initial ischemia/reperfusion injury on the transplanted kidney. Transplantation. 1997;64(7):945–947. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199710150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lucinskas FW, Ma S, Nusrat A, Parkos CA, Shaw SK. Leukocyte transendothelial migration: a junctional affaire. Semin Immunol. 2002;14(2):105–113. doi: 10.1006/smim.2001.0347. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rabb H, O’Maera YM, Maderna P, Coleman P, Brady HR. Leukocytes, cell adhesion molecules and ischemic acute renal failure. Kidney Int. 1997;51(5):1463–1468. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.200. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molitoris BA, Marss J. The role of cell adhesion molecules in ischemic acute renal failure. Am J Med. 1999;106(5):583–592. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00061-3. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pinheiro HS, Camara NOS, Noronha IL, Maugeri IL, Franco MF, Medina JO, et al. Contribution of CD4+ T cells to the early mechanisms of ischemia-reperfusion injury in a mouse model of acute renal failure. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40(4):557–568. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2007000400015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lai LW, Yong KC, Igarashi S, Lien YHH. A Sphingosine-1-phosphate type 1 receptor agonist inhibits the early T-Cell transient following renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Kid Int. 2007;71(12):1223–1231. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bacon KB, Permack BA, Gardner P, Schall TJ. Activation of dual T cell signaling pathways by the chemokine RANTES. Science. 1995;269(5231):1727–1730. doi: 10.1126/science.7569902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takada M, Nadeu KC, Shaw GD, Marquette KA, Tilney NL. The citokine-adhesion molecule cascade in ischemia-reperfusion injury of the rat kidney. Inhibition by a soluble P-selectin ligand. J Clin Invest. 1997;99(11):2682–2690. doi: 10.1172/JCI119457. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabb H, Mendiola CC, Saba SR, Dietz JR, Smith CW, Bonventre JV, et al. Antibodies to ICAM-1 protect kidneys in severe ischemic reperfusion injury. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;211(1):67–73. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kelly KJ, Williams WW, Colvin RB, Meehan SM, Springer TA, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1-deficient mice are protected against ischemic renal injury. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(4):1056–1063. doi: 10.1172/JCI118498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwacka RM, Zhang Y, Halldorson J, Schlossberg H, Dudus L, Engelhardt JF. CD4+ T-lymphocytes mediate ischemia/reperfusion-induced inflammatory responses in mouse liver. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(2):279–289. doi: 10.1172/JCI119533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takada M, Chandraker A, Nadeu KC, Sayeh MH, Tilney NL. The role of B7 costimulatory pathway in experimental cold ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(5):1199–1203. doi: 10.1172/JCI119632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burne MJ, Daniels F, Ghandour A, Mauiyyedi S, Colvin RB, O’Donnell MP. Identification of the CD4+ T Cell as a major pathogenic factor in ischemic acute renal failure. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(9):1283–1290. doi: 10.1172/JCI12080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Land WG. The role of postischemic reperfusion injury and other nonantigen-dependent inflammatory pathways in transplantation. Transplantation. 2005;79(5):505–514. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000153160.82975.86. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yarlagadda SG, Coca SG, Garg AX, Doshi M, Poggio E, Marcus RJ, et al. Marked variation in the definition and diagnosis of delayed graft function: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(9):2995–3003. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ojo AO, Wolf RA, Held PJ, Prot FK, Schmouder RL. Delayed graft function: risk factors and implications for renal allograft survival. Transplantation. 1997;63(7):968–974. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199704150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Azevedo LS, Castro MC, Carvalho DB. Incidência de função retardada do enxerto em transplantes renais no Brasil. J Bras Transp. 2004;7:82–85. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Requião-Moura LR, Durão Mde S, Tonato EJ, Matos AC, Ozaki KS, Câmara NO, et al. Effects of ischemia and reperfusion injury on long-term graft function. Transplantation Proceedings. 2011;43(1):70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfaff WW, Howard RJ, Patton PR, Adams VR, Rosen CB, Reed AI. Delayed graft function after renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;65(2):219–223. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199801270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shoskes DA, Halloran PF. Ischemic injury induces altered MHC gene expression in kidney by an interferon-gamma-dependent pathway. Pt 1Transplant Proc. 1991;23(1):599–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shoskes DA, Cecka JM. Deleterious effects of delayed graft function in cadaveric renal transplant recipients independent of acute rejection. Transplantation. 1998;66(12):1697–1701. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199812270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almond PS, Troppmann C, Escobar F, Frey DJ, Matas AJ. Economic impact of delayed graft function. Pt 2Transplant Proc. 1991;23(1): [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yokoyama I, Uchida K, Kobayashi T, Tominaga Y, Orihara A, Takagi H. Effect of prolonged delayed graft function on long-term graft outcome in cadaveric kidney transplantation. Pt 1Clin Transplant. 1994;8(2):101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedland SJ, Shokes DA. Economic impact of delayed graft function and suboptimal kidneys. Transplantation Rev. 1999;13(1):23–30. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cravedi AU, Codreanu I, Satta A, Turturro M, Sghirlanzoni M, Remuzi G, et al. Cyclosporine prolongs delayed graft function in kidney transplantation: are rabbit anti-human thymocyte globulin the answer? Nephron Clin Pract. 2005;101(2):c65–c71. doi: 10.1159/000086224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Troppman C, Gillingham KJ, Gruessner RW, Dunn DL, Payne WD, Najarian JS, et al. Delayed graft function in the absence of rejection has no long-term impact A study of cadaver kidney recipients with good graft function at 1 year after transplantation. Transplantation. 1996;61(9):1331–1337. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199605150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ploeg RJ. Kidney transplantation with the UW and Euro-Collins solutions. A preliminary report of a clinical comparison. Transplantation. 1990;49(2):281–284. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199002000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moers C, Smits JM, Maathuis M-HJ, Treckmann J, van Gelder F, Napieralski BP, et al. Machine perfusion or cold storage in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. N Eng J Med. 2009;360(1):7–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moers C, Pirenne J, Paul A, Ploeg RJ. Machine Preservation Trial Study Group. Machine perfusion or cold storage in deceased-donor kidney transplantation. N Eng J Med. 2012;366(8):770–771. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1111038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonventre JV, Yang L. Cellular pathophysiology of ischemic acute kidney injury. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(11):4210–4221. doi: 10.1172/JCI45161. Review. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yokota N, Daniles F, Crosson J, Rabb H. Protective effect of T cell depletion in murine renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation. 2002;74(6):759–763. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200209270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mueller TF. Thymoglobulin: an immunologic overview. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2003;8(4):305–312. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Beiras-Fernandez A, Chappell D, Hammer C, Thein E. Influence of polyclonal anti-thymocyte globulins upon ischemia-reperfusion injury in a non-human primate model. Transplant Immunology. 2006;15(4):273–279. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goggins W, Pascual M, Powelson J, Magee C, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Farrellm L, et al. A prospective, randomized, clinical trial of intraoperative versus postoperative thymoglobulin in adult cadaveric renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2003;76(5):798–802. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000081042.67285.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Requião-Moura LR, Ferraz E, Matos AC, Tonato EJ, Ozaki KS, Durão MS, et al. Comparison of long-term effect of thymoglobulin treatment in patients with a high risk of delayed graft function. Transplant Proc. 2012;44(8):2428–2433. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]