Highlights

-

•

‘SURE’ is a new patient reported outcome measure of recovery from drug and alcohol dependence.

-

•

‘SURE’ has been developed with significant input from people in recovery.

-

•

‘SURE’ has good face and content validity, acceptability and usability for people in recovery.

-

•

SURE’ comprises 21 items (5 factors) and is psychometrically valid, quick and easy-to-complete.

-

•

‘SURE’ can be used by individuals in private or in a therapeutic context

Keywords: Patient Reported Outcome Measure (PROM), addiction recovery, addiction service users, qualitative methods, psychometrics

Abstract

BACKGROUND

Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) assess health status and health-related quality of life from the patient/service user perspective. Our study aimed to: i. develop a PROM for recovery from drug and alcohol dependence that has good face and content validity, acceptability and usability for people in recovery; ii. evaluate the psychometric properties and factorial structure of the new PROM (‘SURE’).

METHODS

Item development included Delphi groups, focus groups, and service user feedback on draft versions of the new measure. A 30-item beta version was completed by 575 service users (461 in person [IP] and 114 online [OL]). Analyses comprised rating scale evaluation, assessment of psychometric properties, factorial structure, and differential item functioning.

RESULTS

The beta measure had good face and content validity. Nine items were removed due to low stability, low factor loading, low construct validity or high complexity. The remaining 21 items were re-scaled (Rasch model analyses). Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses revealed 5 factors: substance use, material resources, outlook on life, self-care, and relationships. The MIMIC model indicated 95% metric invariance across the IP and OL samples, and 100% metric invariance for gender. Internal consistency and test-retest reliability were granted. The 5 factors correlated positively with the corresponding WHOQOL-BREF and ARC subscales and score differences between participant sub-groups confirmed discriminative validity.

CONCLUSION

‘SURE’ is a psychometrically valid, quick and easy-to-complete outcome measure, developed with unprecedented input from people in recovery. It can be used alongside, or instead of, existing outcome tools.

1. INTRODUCTION

The term ‘recovery’ is widely used within international addictions literature, policy and practice (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment, 2006, Clark, 2008, Laudet, 2007, Laudet, 2009, Scott and Dennis, 2002, White, 1996). Although the concept was once almost exclusively associated with 12-step fellowships and abstinence (Laudet, 2009), there is growing recognition that recovery can be supported by appropriately prescribed medications (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2013, Recovery Orientated Drug Treatment Expert Group, 2012, White, 2012, White and Mojer-Torres, 2010). Recovery is also increasingly associated with achieving benefits in a wide range of life areas, including housing, health, employment, offending, relationships, self-care, use of time, community participation, and general well-being (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2013, HM Government, 2010, Neale et al., 2012, The Scottish Government, 2008). In 2009, Laudet identified a ‘critical’ need for an addiction recovery measure that would capture the multi-dimensional nature of recovery and the views of multiple stakeholder groups, including service users (Laudet, 2009).

Within many areas of medicine, assessment of patients’ views of their own health status is considered essential for improving the quality and cost effectiveness of services and interventions (Dawson, 2009). This has resulted in the development of self-completion questionnaires, rating scales and assessment forms, known as patient reported outcome measures (or PROMs). PROMs assess a patient’s health status or health-related quality of life at a single point in time, give priority to the patient’s − rather than the clinician’s − perspective, and focus on the quality rather than just the quantity of life (Dawson, 2009). This is important since professionals’ assessments of patients’ treatment needs and health status often differ from patients’ own assessments, and patients and professionals may disagree about the relative importance of specific outcomes (Jenkinson, 1994, Neale et al., 2015, Rose et al., 2006, Schwartz et al., 2005, Treloar et al., 2010).

Involving members of the target patient population in generating questions for a new PROM helps to ensure that the measure developed captures all relevant concepts in a meaningful way and that the questions asked are clear and interpretable (Neale et al., 2015, Neale and Strang, 2015, Patrick et al., 2008). Engagement of this kind is best achieved using qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews, focus groups or other open consultation processes (Lasch et al., 2010). After development, PROMs should be subjected to rigorous psychometric testing to ensure that they are reliable, valid, and measure health status and health-related outcomes as objectively as possible (Dawson, 2009, Neale and Strang, 2015).

This paper reports on a study that had two aims: i. to develop a PROM for recovery from drug and alcohol dependence that has good face and content validity, acceptability and usability for people in recovery; ii. to evaluate the psychometric properties and factorial structure of the PROM using suitable statistical techniques. The PROM developed is inherently different from existing outcome tools − such as the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al., 1980), Opiate Treatment Index (OTI; Darke et al., 1992), Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP; Marsden et al., 1998), Brief Treatment Outcome Measure (BTOM; Lawrinson et al., 2005), Treatment Outcomes Profile (TOP; Marsden et al., 2008), and Addiction Dimensions for Assessment and Personalised Treatment (ADAPT; Marsden et al., 2014). It is the first tool to focus specifically on the concept of ‘recovery’ and the only one developed with extensive service user input. Reflecting this, it prioritises outcomes deemed important by people in recovery (rather than clinicians or others) and is intended for self-completion.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

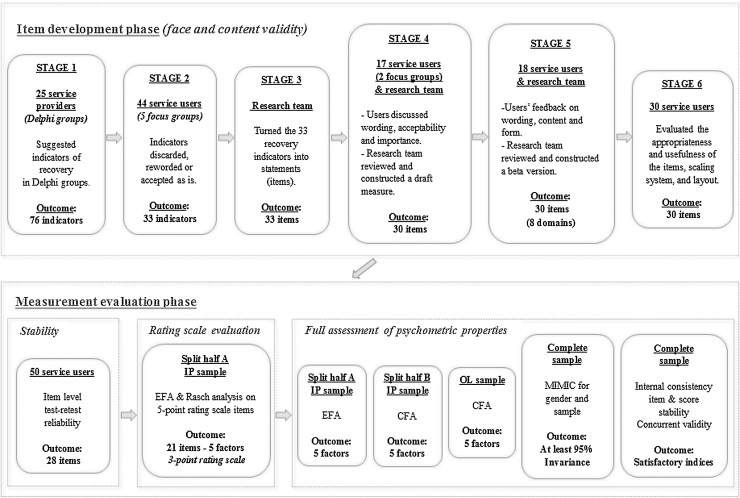

The study received ethical approval from the UK National Research Ethics Service (reference number: 13/LO/1584). Study aim i. (hereafter, ‘item development’) and study aim ii. (hereafter, ‘measurement evaluation’) were each undertaken in stages (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Item development and measurement evaluation.

2.1. Item development

Item development occurred between October, 2013 and January, 2015. The demographic characteristics of the individuals who participated in the various item development stages (25 service providers and 109 service users) are presented in Tables S1-S4 in the supplementary materials. Participating service users were recruited from across London, UK, and received a £15 voucher in compensation for their time; participating service providers received no financial compensation. Throughout the development process, the research team also received support and advice from a separate project advisory group comprising 11 addiction service users who were each paid £20 per consultation.

2.1.1. Stage 1

UK-based addiction psychiatrists, senior residential rehabilitation staff and senior inpatient detoxification staff (N = 25) were asked to identify indicators of recovery in online Delphi groups (Neale et al., 2014a). This had originally been intended as a separate study but the indicators identified were so wide-ranging that they provided a useful starting point for stage 2. At all subsequent developmental stages, service users were encouraged to add new indicators.

2.1.2. Stage 2

Indicators of recovery identified by the 25 service providers and the meaning of recovery more broadly were discussed within 5 focus groups of current and former drug and alcohol service users (N = 44 service users in total) (Neale et al., 2015). The research team discarded indicators that the focus group participants described as irrelevant, inappropriate or offensive and reworded indicators that group participants had deemed unacceptable due to terminology or language. The reworded indicators were combined with indicators that group participants had generally agreed were acceptable.

2.1.3. Stage 3

Members of the research team turned the revised recovery indicators into recovery statements (candidate PROM items)

2.1.4. Stage 4

Two further focus groups of current and former service users debated and ranked the candidate PROM items, focusing on wording, acceptability and importance. The research team then analysed the focus group discussions to produce a draft measure, which was discussed with members of the project advisory group.

2.1.5. Stage 5

A new sample of 18 current and former service users completed the draft measure in person, commenting on wording, content and form. The research team used the service user feedback to generate a beta version of the measure, again in consultation with the project advisory group.

2.1.6. Stage 6

A further 30 current and former services users completed the beta version of the measure in person, commenting on the appropriateness and usefulness of the items, scaling system, and layout. The research team analysed all feedback.

2.2. Measurement evaluation sample

Data collection for the measurement evaluation occurred between February, 2015 and June, 2015.

2.2.1. In Person (IP) sample

Current and former service users (N = 461) were recruited from community-based clinical services, third sector services, and peer support services across London (n = 329), Birmingham (n = 100) and West Sussex (n = 32), UK. These individuals completed a questionnaire that comprised basic demographic, drug use and recovery questions and the recovery measure. Participants were offered refreshments to compensate for their time.

The first 111 (London-based) participants additionally completed two validated measures: i. the WHOQOL-BREF − a quality of life assessment (Skevington et al., 2004), and ii. the ARC − a scale that assesses addiction recovery capital (Groshkova et al., 2013). Of these 111 individuals, the first 50 completed the questionnaire and validated measures a second time, 2–7 days later. These 111 individuals received a £10 supermarket voucher for each questionnaire completed.

2.2.2. Online (OL) sample

To expand the geographical reach of the data collection, an online version of the demographic, drug use and recovery questions and the recovery measure was created using the survey tool BOS (https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk/). The survey link was emailed to 14 recovery-focused organisations based across England and Scotland. No attempt was made to promote the survey more widely and no compensation was offered for completing the survey. In total, 114 individuals responded online from across the UK.

The descriptive indices of the IP and OL samples are presented and compared in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive indices by sample (in person vs online) and comparison.

| In person | Online | Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Males | 333 (86%) | 54 (14%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Females | 128 (68%) | 60 (32%) | 25.68 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Age | |||||

| Mean | 43.0 | 44.7 | t | df | p-value |

| SD | 10.0 | 9.1 | −1.680 | 572 | 0.093 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 362 (76.4%) | 112 (23.6%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Other | 99 (98%) | 2 (2%) | 24.55 | 1 | <0.001 |

| Last month | |||||

| Main substance used: None | 39 (9%) | 38 (34%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Drugs | 113 (25%) | 38 (34%) | 67.56 | 3 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol | 209 (45%) | 19 (17%) | |||

| Both | 100 (22%) | 16 (14%) | |||

| In recovery (self-rated): No | 54 (16%) | 5 (4%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 253 (72%) | 97 (85%) | 10.34 | 2 | <0.001 |

| Homeless: No | 394 (90%) | 110 (100%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 67 (10%) | 3 (0%) | 11.96 | 1 | 0.001 |

| In paid legal work: No | 406 (90%) | 67 (60%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 55 (10%) | 45 (40%) | 49.91 | 1 | <0.001 |

| In residential treatment: No | 317 (90%) | 110 (100%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 33 (10%) | 3 (0%) | 5.47 | 1 | 0.019 |

| In prison: No | 339 (100%) | 112 (100%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 11 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3.61 | 1 | 0.058 |

| Prescribed OPTa: No | 253 (50%) | 104 (90%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 208 (50%) | 10 (10%) | 51.90 | 1 | 0.001 |

| Prescribed medication for alcohol dependenceb: No | 331 (90%) | 103 (90%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 18 (10%) | 10 (10%) | 2.04 | 1 | 0.153 |

| Lifetime: | |||||

| Injected drug: No | 300 (70%) | 78 (70%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 160 (30%) | 36 (30%) | 0.42 | 1 | 0.518 |

| Attendance at mutual aid or support groups: No | 216 (60%) | 50 (40%) | χ2 | df | p-value |

| Yes | 134 (40%) | 63 (60%) | 10.66 | 1 | 0.001 |

aRefers to opioid pharmacotherapy treatment: e.g., methadone, burprenorphine/Subutex, Suboxone, morphine sulphate or diamorphine.

bRefers to: acamprosate or naltrexone.

2.3. Statistical analyses

The latent structure of the new measure was assessed via factor analysis for categorical data using the weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV; Muthén et al., 1997). The IP sample was randomly divided into split half samples; the first sub-sample was used in exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the second one in confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for categorical data. Both measures of absolute and relative fit were assessed, namely the relative chi-square (relative χ2: values close to 2 indicate close fit; Hoelter, 1983), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, values less than 0.8 are required for adequate fit; Browne and Cudeck, 1993), the Taylor-Lewis Index (TLI, values higher than 0.9 are required for close fit; Bentler and Bonett, 1980) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI, values higher than 0.9 are required for close fit; Bentler, 1990).

The adequacy of the rating scale was evaluated according to the recommendations described by Linacre (2004), both within each factor and for the complete set of items. Any item differential functioning (DIF) with respect to the data source (IP vs OL) and gender was assessed using multiple indicator multiple cause (MIMIC) structural equation models (Muthén, 1985).

The reliability of the scale in terms of internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach’s (1951) alpha coefficient. In terms of stability, test-retest reliability was assessed at item level using Cohen’s (1968) weighted Kappa coefficient (κ) and at score level using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC; Koch, 1982).

Concurrent convergent validity was evaluated via correlations with the WHOQOL-BREF and ARC subscale scores (Pearson’s r). Discriminative validity was assessed via score differences between participant sub-groups based on their responses to demographic, drug use and recovery questions in the questionnaire (t-test for 2 groups; one-way ANOVA for 3 or more groups).

Data analyses were conducted using R (R Core Team, 2013), Facets (Linacre, 2015), and Mplus (Muthén and Muthén, 1998) statistical packages.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Item development outcome

In Stage 1, the online Delphi groups with service providers generated 76 indicators of recovery that comprised 15 broad domains (Table S5; Neale et al., 2014a). The Stage 2 focus group participants identified multiple problems with the 76 indicators, suggesting that many were irrelevant, inappropriate, contradictory or offensive (Neale et al., 2015). Indicators were discarded, reworded or accepted accordingly, generating a new set of 33 recovery indicators. In Stage 3, the 33 recovery indicators were turned into 33 recovery statements (candidate items) by members of the research team (Table S6). Analyses from the two Stage 4 service user focus groups resulted in further rewording of items, deletion of items and the inclusion of some new items. This generated a draft recovery measure comprising 30 items (Table S7).

In Stage 5, the researchers used feedback from the next sample of 18 current and former service users to amend the items again, so generating a beta version of the measure (30 items across 8 domains) (Table S8). Each of the 30 items utilized a five-point, ordinal (polytomous) rating scale, with scores ranging from 0-4, except for the first four items which were reversed scored (total score range 0-120). An additional 8 questions at the end of the measure were not scored, but allowed individuals to rank each domain on a four-point Likert scale for its importance to them personally.

In the final development stage (Stage 6), 30 individuals completed the beta version recovery measure. In total, 29 (97%) reported the measure was easy to complete, 28 (93%) reported it was easy to understand, 25 (83%) reported the length was about right, and 21 (70%) reported that it covered everything important. Items that individuals identified as missing from the measure were reviewed, but all had already been considered within the earlier developmental stages and so were discounted. Time to complete the measure ranged from 4–15 minutes. Fourteen individuals (47%) volunteered that they had enjoyed completing it and none stated that they had disliked completing it. All of the domains were consistently ranked as ‘important’ or ‘very important’ by at least 28 (93%) participants. Good face and content validity, acceptability and usability for people in recovery were confirmed.

3.2. Measurement evaluation

3.2.1. Item refinement

Using the 5-point (0-4) rating scale, Cohen’s weighted κ coefficient was < 0.4 for 2 of the 30 items (‘I have abused medication prescribed to me by a doctor’ and ‘I have had enough company and spent enough time with other people’). These two items were therefore omitted from the measure on the grounds of low stability (Landis and Koch, 1977). This resulted in a shortened 28-item recovery measure that was used for the rating scale evaluation.

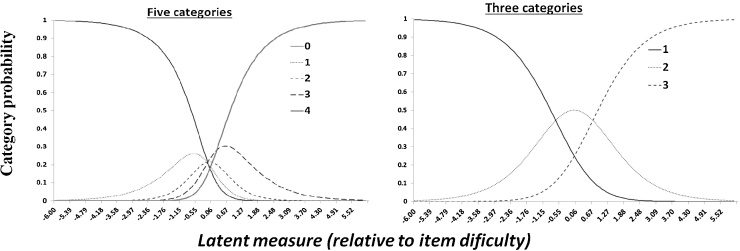

Following Linacre (2004), we first considered whether adjacent categories in the rating scale needed to be combined. As Rasch analysis assumes unidimensionality, an initial exploratory factor model was fitted and this indicated five factors. Analyses of each of the five factors and of the complete scale revealed that two pairs of categories (“0-1” and “3-4”) should be merged. This is illustrated in Fig. 2 which shows that, when five categories were used, the probability of responding “0” was higher than the probability of responding “1” at the lower end of the latent trait even when category “1” reached its peak. That is, at the point on the latent continuum where category “1” occurred more often than at any other point, participants were still more likely to choose “0”, making the distinction between the two response options redundant. Similarly, the probability of responding “4” was always higher than the probability of responding “3” at the higher end of the latent trait. This phenomenon is usually referred to as distorted thresholds (see Linacre, 2004 for details). In contrast, when a 3-point (1-3) rating scale was used, there was a natural transition on the ordered categories in terms of the amount of the latent trait (x-axis) and the probability of choosing each category (y-axis).

Fig. 2.

Category probabilities over the latent trait for the 5-point and for the 3-point rating scales.

The preliminary results were also used to omit items that: i. showed low loadings across all factors; ii. reduced the alpha coefficient of the total scale or within a factor (low construct validity); or iii. had very high loadings in multiple factors (high complexity) (Table S9). These additional omissions produced a final 21-item measure. Service users in the project advisory group confirmed that the 21-item measure retained good face and content validity, helped identify a name for the new measure, and facilitated wider face-to-face and online consultation with service users to confirm the name: ‘Substance Use Recovery Evaluator’ or ‘SURE’. Full psychometric assessment (reported below) was therefore undertaken using the final 21-item measure and a 3-point (1-3) rating scale.

3.2.2. Full assessment of psychometric properties

3.2.2.1. Factor structure

Exploratory factor analysis for categorical items was performed using a random half of the IP sample (N = 231). The first five eigenvalues were 9.6, 1.9, 1.5, 1.2, and 1.0. The five-factor solution demonstrated close fit to the data with RMSEA = 0.046, relative χ2 = 1.5 and RMSR = 0.041. Increasing the number of factors resulted in similar fit indices so, consistent with the parsimony axiom, the five-factor solution was accepted. Table 2 shows the loadings of the items on the factors (Promax rotation), according to which the underlying dimensions were named: “substance use” (SU), “material resources” (MR), “outlook on life” (OK), “self-care” (SC), and “relationships” (RE).

Table 2.

EFA loadings (Promax rotation) for the first random half of the IP sample (N = 231) and CFA loadings (in parentheses) for the second random half of the IP sample (N = 230).a

| No | Item | Substance Use (SU) | Material Resources (MR) | Outlook on Life (OK) | Self-care (SC) | Relationships (RE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Drunk too much | 0.79 (1.00) | −0.30 | |||

| 2 | Used street drugs | 0.52 (1.13) | ||||

| 3 | Had cravings | 0.44 (1.16) | ||||

| 5 | Coped with problemsb | 0.93 (1.58) | ||||

| 7 | Managed pains and ill healthb | 0.77 (1.70) | ||||

| 16 | Had non drug hobbies and interests | 0.59 (1.78) | ||||

| 12 | Had stable housing | 0.62 (1.00) | ||||

| 13 | Had a regular income | 0.87 (1.02) | ||||

| 14 | Been managing money | 0.57 (0.91) | ||||

| 17 | Felt happy with quality of life | 0.90 (1.00) | ||||

| 18 | Felt positive | 0.94 (1.02) | ||||

| 19 | Had realistic hopes and goals | 0.66 (0.91) | ||||

| 4 | Looked after mental health | 0.48 (1.00) | ||||

| 6 | Looked after physical health | 0.66 (1.41) | ||||

| 8 | Eaten a good diet | 0.95 (1.18) | ||||

| 9 | Slept well | 0.44 (1.10) | ||||

| 15 | Had a good daily routine | 0.31 | 0.42 (1.44) | |||

| 10 | Got on well with people | 0.45 (1.00) | ||||

| 11 | Felt supported by people | 0.40 | 0.43 (1.08) | |||

| 20 | Been treated with respect | 0.82 (1.10) | ||||

| 21 | Treated others with respect | 0.57 (0.75) |

All loadings presented were significant (p < 0.05).

Without drugs or alcohol.

Confirmatory factor analysis for categorical items was next performed using the second random half of the IP sample (N = 230). The first model implemented used the one factor solution to check that the scale was not unidimensional. As anticipated, the one factor solution did not show close fit to the data (relative χ2 = 3.2, with RMSEA = 0.098, TLI = 0.91, CFI = 0.92). In contrast, the EFA suggested solution did demonstrate close fit to the data (relative χ2 = 1.7, with RMSEA = 0.055, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.98). Thus, the 5-factor solution suggested by the EFA was confirmed by the CFA (CFA loadings are presented in Table 2). The five-factor model also had close fit in the OL sample (RMSEA = 0.055, relative χ2 = 1.3, TLI = 0.99, CFI = 0.99).

3.2.2.2. Differential item functioning

The next step in the analysis was to test whether the model was invariant across the two samples: IP and OL. The fit of the MIMIC model was adequate (relative χ2 = 2.8, RMSEA = 0.057, TLI = 0.97, CFI = 0.98). Only one direct effect was significant: individuals who completed the questionnaire OL had increased probability of scoring higher in “managed pains and ill health” than individuals who completed IP for the same levels of recovery (effect = 0.536, se = 0.2, p = 0.014). These results indicated metric invariance across the two groups for 95% of the items. For the DIF assessment of gender, the complete sample (IP and OL) was used. With respect to gender, none of the direct effects was significant (100% metric invariance, relative χ2 = 2.7, RMSEA = 0.055, TLI = 0.98, CFI = 0.98).

3.2.2.3. Descriptive indices and associations with sample characteristics

The descriptive indices for the five factors by gender and total score (TS) are presented in Table 3. Females, scored higher than males in the SU and MR factors. In terms of differences between the IP and OL samples, the OL sample scored significantly higher in all factors (p < 0.001 in all cases), adding up to a mean difference of 8 units (s.e.=0.91) for the total score (t = 8.59, df = 573, p < 0.01). The inter-correlations across the factors and total score were positive, significant and moderate to strong (Table 4). Age correlated weakly with the SU and MR factors as well as with the total score, indicating that individuals tended to have higher scores as age increased.

Table 3.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and score differences by gender.

| a | Females |

Males |

Complete Sample |

Comparison | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (Median) |

SD (min-max) |

Mean (Median) |

SD (min-max) |

Mean (Median) |

SD (min-max) |

|||

| SU | 0.83 | 13.5 (14) | 3.6 (6-18) | 12.7 (12) | 3.5 (6-18) | 13 (13) | 3.6 (6-18) | t = 2.57, df = 573, p = 0.010 |

| SC | 0.82 | 9.2 (9) | 2.9 (5-15) | 9.1 (9) | 2.6 (5-15) | 9.1 (9) | 2.7 (5-15) | t = 0.75, df = 573, p = 0.451 |

| OK | 0.87 | 5.1 (5) | 1.8 (3-9) | 5.3 (6) | 1.8 (3-9) | 5.2 (6) | 1.8 (3-9) | t = −1.19, df = 573, p = 0.235 |

| RE | 0.74 | 8.6 (8) | 2.0 (4-12) | 8.5 (8) | 1.9 (4-12) | 8.5 (8) | 1.9 (4-12) | t = 0.37, df = 573, p = 0.715 |

| MR | 0.68 | 7.5 (8) | 1.5 (3-9) | 6.7 (7) | 1.8 (3-9) | 7 (7) | 1.7 (3-9) | t = 5.27, df = 430*, p < 0.001 |

| TSa | 0.92 | 43.9 (44.5) | 9.6 (24-63) | 42.3 (42) | 9.3 (22-63) | 42.8 (43) | 9.4 (22-63) | t = 1.93, df = 573, p = 0.054 |

*equal variances not assumed.

Total Score.

Table 4.

Factor, total score and age inter-correlations.

| SU | SC | OK | RE | MR | TS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | 0.6 (<0.001) | |||||

| OK | 0.5 (<0.001) | 0.7 (<0.001) | ||||

| RE | 0.5 (<0.001) | 0.6 (<0.001) | 0.6 (<0.001) | |||

| MR | 0.5 (<0.001) | 0.5 (<0.001) | 0.4 (<0.001) | 0.5 (<0.001) | ||

| TS | 0.8 (<0.001) | 0.9 (<0.001) | 0.8 (<0.001) | 0.8 (<0.001) | 0.7 (<0.001) | |

| Age | 0.2 (<0.001) | 0.1 (0.098) | <0.1 (0.478) | 0.1 (0.074) | 0.2 (<0.001) | 0.1 (0.003) |

3.3. Reliability

Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was high in the IP sample (alpha = 0.91), the OL sample (0.93) and when all individuals were considered together (0.92), so indicating high internal consistency of the items. No problematic items were found in terms of internal consistency or low item-total correlations. The reliability coefficients were also satisfactory at factor level, albeit lower than for the total questionnaire due to the small number of items in each factor (Table 3).

When the test-retest analyses were repeated using the 3-point (1-3) rating scale, Cohen’s weighted κ coefficient for all 21 items varied from 0.4 to 0.8, representing ‘moderate to substantial agreement’ according to Landis and Koch (1977). The ICC was 0.9 for the total score and 0.6-0.8 for the five factors (Table S9). Additionally, no significant mean differences were found between the scores of the factors or the total score, meaning that test-retest reliability was granted for the final 21-item measure (Table S10).

3.3.1. Validity

The correlations presented in Table 5 confirm that the 5 factors of the new recovery measure correlated positively with the WHOQOL-BREF and the ARC subscale scores, demonstrating appropriate concurrent convergent validity. Moreover, the highest coefficients emerged when the content of the scales were matching.

Table 5.

Correlation coefficients for the recovery measure scores and subscale scores of the WHOQOL-BREF and the ARC.a

|

Grey values correspond to non-significant correlations after adjusting for multiple comparisons (p-value within parenthesis); for the remaining coefficients, the p-value was <0.001.

In testing for discriminative validity, we found that people who reported that they had been in paid work in the last month had a significantly higher total score on the 21-item recovery measure than those who said that they had not been in paid work (‘in paid work’: mean = 45.9, sd = 9.6; ‘not in paid work’: mean = 42.1; sd = 9.2, t = 3.70, df = 571, p < 0.001). People who reported that they had been homeless in the last month had a lower total recovery score than those who reported that they had not been homeless (‘homeless’: mean = 36.5, sd = 8.3; ‘not homeless’: mean = 43.7, sd = 9.2; t = −6.19, df = 572, p < 0.001). Additionally, people who reported that had been in prison in the last month had a lower total recovery score than those who reported that they had not been in prison (‘in prison’: mean = 35.9, sd = 6.4; ‘not in prison’: mean = 43.5, sd = 9.3; t = −2.68, df = 460, p = 0.008).

We also found significant differences in mean total recovery scores based on whether or not participants self-reported use of any drugs or alcohol in the last year. Specifically, one way ANOVA indicated that the total recovery score was significantly higher (F[3,568] = 45.7, p < 0.001) for individuals who reported that they had not used any substances (drugs or alcohol) (mean = 52.0, sd = 6.7, N = 77), than for individuals reporting alcohol use only (mean = 44.3, sd = 9.6, N = 151), individuals reporting drug use only (mean = 40.3, sd = 8.3, N = 228), and individuals reporting both drug and alcohol use (mean = 39.23, sd = 8.2, N = 116). According to the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons, all pairwise mean differences were significant (p < 0.001 in all cases).

In terms of participants’ self-evaluation of their recovery status (i.e., whether or not they currently considered themselves to be ‘in recovery’), one way ANOVA indicated that individuals who reported that they were currently ‘in recovery’ scored significantly higher (mean = 45.2, sd = 9.1, N = 350) than those who replied negatively (mean = 38.1, sd = 8.2, N = 59) and those who were unsure (mean = 37.3, sd = 7.3, N = 55; F[2,461] = 30.70, p < 0.001). According to the Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons, all pairwise mean differences were again significant (p < 0.001 in all cases).

4. DISCUSSION

Extensive developmental work, comprising qualitative and quantitative methods, with significant input from service users, was undertaken to develop items for ‘SURE’, a new PROM for recovery from drug and alcohol dependence. The final measure comprises 21 items and 5 factors: “substance use” (6 items), “material resources” (3 items), “outlook on life” (3 items), “self-care” (5 items) and “relationships” (4 items). Members of a service user project advisory group confirmed face and content validity and service users helped to determine the name of the new measure. Analyses established the measure’s factor structure, invariance, reliability and validity. SURE is distinct from other addiction outcome measures given its focus on ‘recovery’, and overall prioritisation of the service user perspective in both its development and intended use.

The five factors identified are consistent with a concept of recovery that encompasses a range of life areas (Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs, 2013, HM Government, 2010, Neale et al., 2012, The Scottish Government, 2008). Only 6/21 items explicitly refer to substance use, highlighting how it is possible to be in ‘recovery’, despite some drinking or drug taking. This reflects the more inclusive (non-abstinence) approach to recovery that has gained traction in recent years (Duke et al., 2013; Recovery Orientated Drug Treatment Expert Group, 2012). That there is no standalone employment item is also notable given the UK Government’s repeated emphasis on drug users having to secure paid work (Department for Work and Pensions, 2015, Home Office, 2008, The Scottish Government, 2008). Instead, ‘SURE’ has an item that refers to ‘having a regular income (from benefits, work or other legal sources)’, and a related item on ‘having a good daily routine’. These alternative indicators implicitly acknowledge that individuals may not be able to secure paid work for structural reasons unrelated to personal recovery (e.g., lack of jobs or employers’ lack of willingness to employ people with a history of substance use or related criminal activity) (Kemp and Neale, 2005) and that stability and having meaningful activity are more valid indicators of recovery.

Each of the five factors is internally coherent. For example, the 6 substance use items are the only items that explicitly refer to drinking or drug use and the four relationship items are the only four that explicitly relate to ‘people’. The only factor that did not correlate significantly with the WHOQOL-BREF and the ARC was ‘material resources’. This warrants consideration. Previous qualitative research (Neale et al., 2012, Neale et al., 2014b) and the focus groups we conducted in developing the measure (Neale et al., 2015) have found that people in recovery want stable housing, regular income and money to pay bills. However, they do not generally covet material good or wealth because i. disposable income can become a temptation to buy drugs or alcohol and ii. they tend to prioritise relationships and people over possessions. This may help to explain why our 3 material resource items correlated well with recovery in general, but less well with substance use, and other general quality of life indicators.

‘SURE’ items are completed using a 5-point rating scale, but scored using a 3-point scale (the two categories at the lower end of the latent trait are combined, as are the two categories at the higher end of the latent trait). Total ‘SURE’ scores therefore range from 21-63. The 5-point scale has been retained for completion purposes because: i. service users repeatedly told us that they liked having five options to consider; ii. it is not difficult to re-score the items post completion; and iii. we noticed that service users completing the measure often paused thoughtfully when deciding how to respond to the five categories, and then spontaneously discussed their thoughts with the researcher. As we have previously argued (Neale and Strang, 2015), completion of the PROM seldom simply generated a numeric score. Rather, it prompted people to reflect on and volunteer potentially valuable contextual information about their lives and circumstances that might be relevant in a therapeutic context.

As with all new measures, there are limitations. First, we note that ‘SURE’ is not tailored for use in residential settings (e.g., residential detoxification, residential rehabilitation or prison). Although we included residential treatment clients in our developmental work to ensure that their views were captured, service user feedback indicated that several items were difficult for residential clients to answer. This is because responses to items such as ‘eaten a good diet’, ‘having stable housing’, ‘having a good daily routine,’ and ‘managing money’ tend to be affected by the structure and routine of the residential setting and so beyond individual control. Service users living in residential settings were therefore not included in the sample used for the measurement evaluation. Second, additional validity testing (e.g., criterion or predictive validity) would be desirable. Third, language and terminology are historically and culturally sensitive. The wording of items in ‘SURE’ (particularly those relating to substance use) need to be carefully reviewed to find culturally appropriate terms if the measure is to be used in other countries.

In contrast, ‘SURE’ has a number of significant strengths. First, service users have played a fundamental role in its design and content, and it is found to have good face validity. This level of service user engagement is unprecedented in any existing validated addiction outcome measure. Second, the measure has been designed by a careful and considered blending of qualitative methods (with their focus on subjective meaning and understanding) and more objective quantitative techniques. This capitalises on the strengths of each to ensure a robust development and validation process. Third, the study participants were diverse in terms of age, ethnicity, drugs used, and geographical location, thus providing reassurances in terms of inclusion and diversity. Fourth, the measure retains five unscored questions at the end that encourage participants to reflect on how important each of the factors is to them personally. Service users liked this final component. As a member of the advisory group explained: “I like the way that it ends… this part reinforces that the service user has a big part to play; that this is what’s important to them as individuals”.

‘SURE’ is a psychometrically valid, quick and easy-to-complete measure, developed with significant input from people in recovery. It can be used by individuals to monitor and reflect on their own recovery journeys, either in private or in the context of a therapeutic relationship. It can also be used to assess treatment outcomes at a service level or by researchers seeking to evaluate new interventions. As such it can be used either alongside, or instead of, existing outcome tools. In the coming months we will continue our work by exploring opportunities for developing online and app versions with an integrated scoring system and graphical displays; collecting longitudinal data to test for predictive validity; seeking collaborators for international validation; and adapting the methodology for other drug and alcohol related PROMs, PREMs (Patient Reported Experience Measures) and CROMs (Carer Reported Outcome Measures).

ROLE OF FUNDING SOURCE

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. JN, SV, DR, JS & TW are all funded or part-funded by the Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

CONTRIBUTORS

JN led on all aspects of the study and paper writing. EF, DP, PL & LM contributed to data collection. PL played a key role in service user engagement. JM and SV led on the statistical analyses. SV wrote sections of the paper, with input from JM & JS. All authors contributed to the design of the study and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

JS a researcher and clinician who has worked with a range of types of treatment and rehabilitation service-providers. JS is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre for Mental Health at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London. He has also worked with a range of governmental and non-governmental organisations, and with pharmaceutical companies to seek to identify new or improved treatments from whom he and his employer (King’s College London) have received honoraria, travel costs and/or consultancy payments. This includes work with, during past 3 years, Martindale, Reckitt-Benckiser/Indivior, MundiPharma, Braeburn/MedPace and trial medication supply from iGen. His employer (King’s College London) has registered intellectual property on a novel buccal naloxone formulation and he has also been named in a patent registration by a Pharma company as inventor of a concentrated nasal naloxone spray. For a fuller account, see JS’s web-page at http://www.kcl.ac.uk/ioppn/depts/addictions/people/hod.aspx. The authors declare that they have no financial or personal relationships with other people or organizations that could inappropriately influence this research.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all research participants for their time; members of our service user advisory group for their interest and contributions; Professor Ray Fitzpatrick for his advice and support; and Shabana Akhtar, Bethan Dalton, Dr Charlotte Tompkins, and Dr Carly Wheeler for their assistance with data collection. We are also grateful to the many services that provided access to their clients.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.06.006. Further information on how to access SURE can be found at http://www.kcl.ac.uk/ioppn/depts/addictions/Scales,-measures-&-instruments/SURE-Substance-Use-Recovery-Evaluator.aspx

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs . Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs; London: 2013. What Recovery Outcomes Does The Evidence Tell Us We Can Expect? Second Report Of The Recovery Committee. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P.M. Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychol. Bull. 1990;107:238–246. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bentler P.M., Bonett D.G. Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980;88:588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Browne M.W., Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen K.A., Long J.S., editors. Testing Structural Equation Models. Sage; Newbury Park: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Substance Abuse Treatment . Substance Abuse And Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2006. National Summit On Recovery: Conference Report. [Google Scholar]

- Clark W. Aligning Concepts, Practice, And Contexts To Promote Long-Term Recovery: An Action Plan. IRETA; Philadelphia: 2008. Recovery-Oriented Systems Of Care: SAMHSA/CSAT’s Public Health Approach To Substance Use Problems And Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Weighed kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968;70:213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;22:297–334. [Google Scholar]

- Darke S., Hall W., Wodak A., Heather N., Ward J. Development and validation of a multi-dimensional instrument for assessing outcome of treatment among opiate users: the Opiate Treatment Index. Br. J. Addict. 1992;87:733–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1992.tb02719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson J. Measuring health status. In: Neale J., editor. Research Methods For Health And Social Care. Palgrave; London: 2009. pp. 181–194. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Work and Pensions, 2015. An Independent Review Into The Impact On Employment Outcomes Drug Or Alcohol Addiction, And Obesity. Call For Evidence. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/448830/employment-outcomes-drug-alcohol-obesity–independent-review.pdf (accessed 12th March 2016).

- Duke K., Herring R., Thickett A., Thom B. Substitution treatment in the era of ‘recovery’: an analysis of stakeholder roles and policy windows in Britain. Subst. Use Misuse. 2013;48:966–976. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.797727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groshkova T., Best D., White W. The Assessment of Recovery Capital: properties and psychometrics of a measure of addiction recovery strengths. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2013;32:187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2012.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Government H.M. HM Government; London: 2010. Drug Strategy 2010: ‘Reducing Demand, Restricting Supply, Building Recovery: Supporting People To Live Drug Free Life’. [Google Scholar]

- Hoelter J.W. The analysis of covariance structures: goodness of fit indices. Sociol. Methods Res. 1983;11:325–344. [Google Scholar]

- Home Office . The 2008 Drug Strategy. Home Office; London: 2008. Drugs: Protecting Families And Communities. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson C. Measuring health and medical outcomes: an overview. In: Jenkinson C., editor. Measuring Health And Medical Outcomes. UCL Press; London: 1994. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp P.A., Neale J. Employability and problem drug users. Crit. Soc. Pol. 2005;25:28–46. [Google Scholar]

- Koch G.G. Intraclass correlation coefficient. In: Kotz S., Johnson N.L., editors. Encyclopedia of Statistical Sciences 4. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1982. pp. 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Landis J.R., Koch G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lasch K.E., Marquis P., Vigneux M., Abetz L., Arnould B., Bayliss M., Crawford B., Rosa K. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual. Life Res. 2010;19:1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A.B. What does recovery mean to you? Lessons from the recovery experience for research and practice. J. Subst. Abuse Treat. 2007;33:243–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudet A.B. Environmental Scan of Measures of Recovery. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, U.S. Rockville, MD. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- Lawrinson P., Copeland J., Indig D. Development and validation of a brief instrument for routine outcome monitoring in opioid maintenance pharmacotherapy services: the brief treatment outcome measure (BTOM) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linacre J.M. Optimising rating scale category effectiveness. In: Smith J.E.V., Smith R.M., editors. Introduction To Rasch Measurement: Theory, Models, And Applications. JAM Press; Maple Grove, MN: 2004. pp. 258–275. [Google Scholar]

- Linacre, J.M., 2015. Facets Computer Program For Many-Facet Rasch Measurement, Version 3.71.4. Winsteps.com, Beaverton, Oregon.

- Marsden J., Eastwood B., Ali R., Burkinshaw P., Chohan G., Copello A., Burn D., Kelleher M., Mitcheson L., Taylor S., Wilson N., Whiteley C., Day E. Development of the Addiction Dimensions for Assessment and Personalised Treatment (ADAPT) Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;139:121–131. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden J., Farrell M., Bradbury C., Dale-Perera A., Eastwood B., Roxburgh M., Taylor S. Development of the treatment outcomes profile. Addiction. 2008;103:1450–1460. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden J., Gossop M., Stewart D., Best D., Farrell M., Lehmann P., Edwards C., Strang J. The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP): a brief instrument for assessing treatment outcome. Addiction. 1998;93:1857–1867. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1998.9312185711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A.T., Luborsky L., Woody G.E., O'Brien C.P. An improved diagnostic evaluation instrument for substance abuse patients The Addiction Severity Index. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1980;168:26–33. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198001000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B. A method for studying the homogeneity of test items with respect to other relevant variables. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 1985;10:121–132. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B., du Toit S.H.C., Spisic D. 1997. Robust inference using weighted least squares and quadratic estimating equations in latent variable modelling with categorical and continuous outcomes. Unpublished technical report.

- Muthén L.K., Muthén B.O. 6th edition. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles, CA: 1998. Mplus User's Guide. 1998-2011. [Google Scholar]

- Neale J., Finch E., Marsden J., Mitcheson L., Rose D., Strang J., Tompkins C., Wheeler C., Wykes T. How should we measure addiction recovery? Analysis of service provider perspectives using online Delphi groups. Drugs Educ. Prev. Policy. 2014;21:310–323. [Google Scholar]

- Neale J., Nettleton S., Pickering L. Gender sameness and difference in recovery from heroin dependence: a qualitative exploration. Int. J. Drug Policy. 2014;25:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J., Pickering L., Nettleton S. Royal Society of Arts; London: 2012. The Everyday Lives Of Recovering Heroin Users. [Google Scholar]

- Neale J., Strang J. Philosophical ruminations on measurement: methodological orientations of patient reported outcome measures (PROMS) J. Ment. Health. 2015;24:123–125. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1036978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale J., Tompkins C., Wheeler C., Finch E., Marsden J., Mitcheson L., Rose D., Wykes T., Strang J. You’re all going to hate the word ‘recovery’ by the end of this: service users’ views of measuring addiction recovery. Drugs: Educ. Prev. Polic. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D., Guyatt G., Acquadro C. Patient-reported outcomes. In: Higgens J., Green S., editors. Cochrane Handbook For Systematic Reviews Of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons; Chichester: 2008. pp. 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2013. R: A Language And Environment For Statistical Computing.http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Recovery Orientated Drug Treatment Expert Group . National Drug Treatment Agency for Substance Misuse; London: 2012. Medications In Recovery: Re-Orientating Drug Dependence Treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Rose D., Thornicroft G., Slade M. Who decides what evidence is?: Developing a multiple perspectives paradigm in mental health. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2006;429(Suppl. 113):109–114. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz C., Sprangers M.A., Fayers P. Response shift: you know it’s there, but how do you capture it? Challenges for the next phase of research. In: Fayers P., Hays R., editors. Assessing Quality Of Life In Clinical Trials. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2005. pp. 275–290. [Google Scholar]

- Scott C.K., Dennis M.L. Chestnut Health Systems; Bloomington, IL: 2002. Recovery Management Checkup (RMC) Protocol For People With Chronic Substance Use Disorder. [Google Scholar]

- Skevington S.M., Lofty M., O’Connell K.A. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial A report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual. Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Scottish Government . The Scottish Government; Edinburgh: 2008. The Road To Recovery: A New Approach To Tackling Scotland's Drug Problem. [Google Scholar]

- Treloar C., Newland J., Rance J., Hopwood M. Uptake and delivery of hepatitis C treatment in opiate substitution treatment: perceptions of clients and health professionals. J. Viral Hepat. 2010;17:839–844. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2009.01250.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W. 2nd edition. Center City; Hazelden: 1996. Pathways From The Culture Of Addiction To The Culture Of Recovery: A Travel Guide For Addiction Professionals. [Google Scholar]

- White W. Medication-assisted recovery from opioid addiction: historical and contemporary perspectives. J. Addict. Dis. 2012;31:199–206. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.694597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W., Mojer-Torres L. Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center, Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health and Mental Retardation Services and Northeast Addiction Technology Transfer Centre; Chicago, IL: 2010. Recovery-Orientated Methadone Maintenance. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.