Abstract

Background

We have previously reported successful induction of transient mixed chimerism and long-term acceptance of renal allografts in MHC-mismatched nonhuman primates. In this study, we attempted to extend this tolerance induction approach to islet allografts.

Methods

A total of eight recipients underwent MHC mismatched combined islet and bone marrow (BM) transplantation after induction of diabetes by streptozotocin. Three recipients were treated after a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen that includes low dose total body and thymic irradiation, horse ATG (Atgam), six doses of anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody (mAb) and a one month course of cyclosporine (CyA) (Islet-A). In Islet-B, anti-CD8 mAb was administered in place of CyA. In Islet-C, two recipients were treated with Islet-B but without Atgam. The results were compared with previously reported results of eight cynomolgus monkeys that received combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation (Kidney-A) following the same conditioning regimen used in Islet-A.

Results

The majority of Kidney/BM recipients achieved long-term renal allograft survival after induction of transient chimerism. However, prolonged islet survival was not achieved in similarly conditioned Islet/BM recipients (Islet-A), despite induction of comparable levels of chimerism. In order to rule out islet allograft loss due to calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) toxicity, three recipients were treated with anti-CD8 mAb in place of CNI. Although these recipients developed significantly superior mixed chimerism and more prolonged islet allograft survival (61, 103, and 113 days), islet function was lost soon after the disappearance of chimerism. In Islet-C recipients, neither prolonged chimerism nor islet survival was observed (30 and 40 days).

Conclusion

Significant improvement of mixed chimerism induction and islet allograft survival were achieved with a CNI-free regimen that includes anti-CD8 mAb. However, unlike the kidney allograft, islet allograft tolerance was not induced with transient chimerism. Induction of more durable mixed chimerism may be necessary for induction of islet allograft tolerance.

Keywords: Kidney transplantation, Islet transplantation, Nonhuman primate, Mixed chimerism

Introduction

The recent development of a potent induction immunotherapy protocol by the Minnesota group, using T-cell depleting antibody and TNF-α inhibition, has significantly improved short-term results of pancreatic islet transplantation (PITx) (1). However, 5-year graft survival was still only 50%, which is significantly lower than the survival rate for solid organ transplants. In addition to alloimmunity, multiple factors, such as exhaustion (21) and autoimmunity (24), may be involved in the loss of the islet allograft, but islet injury by chronic calcineurin inhibitor (CNI) use may also play an important role (3). Therefore, induction of tolerance of the islet allograft remains a desirable solution for improving long-term results of PITx (1,16,19).

We have previously reported a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen that can induce mixed hematopoietic chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in nonhuman primates (NHPs) (5,8,11). This approach has been successfully translated to both human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matched and HLA mismatched human kidney transplant recipients with the longest immunosuppression free survival of the latter group now exceeding 12 years (6,9,10). In the current study, we attempted to extend this mixed chimerism approach to islet transplantation in nonhuman primates.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male cynomolgus monkeys weighing 3–5 kg were used (Charles River Primates, Wilmington, MA). Recipient and donor pairs were selected for compatible ABO blood types and mismatched cynomolgus leukocyte (CyLA) major histocompatibility complex (MHC) antigens. CyLA class I antigenic disparity was determined by serologic typing with allele-specific anti-HLA class I monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) that cross-react with cynomolgus alleles. CyLA class II antigenic disparity was confirmed by a positive mixed lymphocyte response and polymerase chain reaction assay using primers specific to cynomolgus D-related (DR). All surgical procedures and postoperative care of animals were performed in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines for the care and use of primates and were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

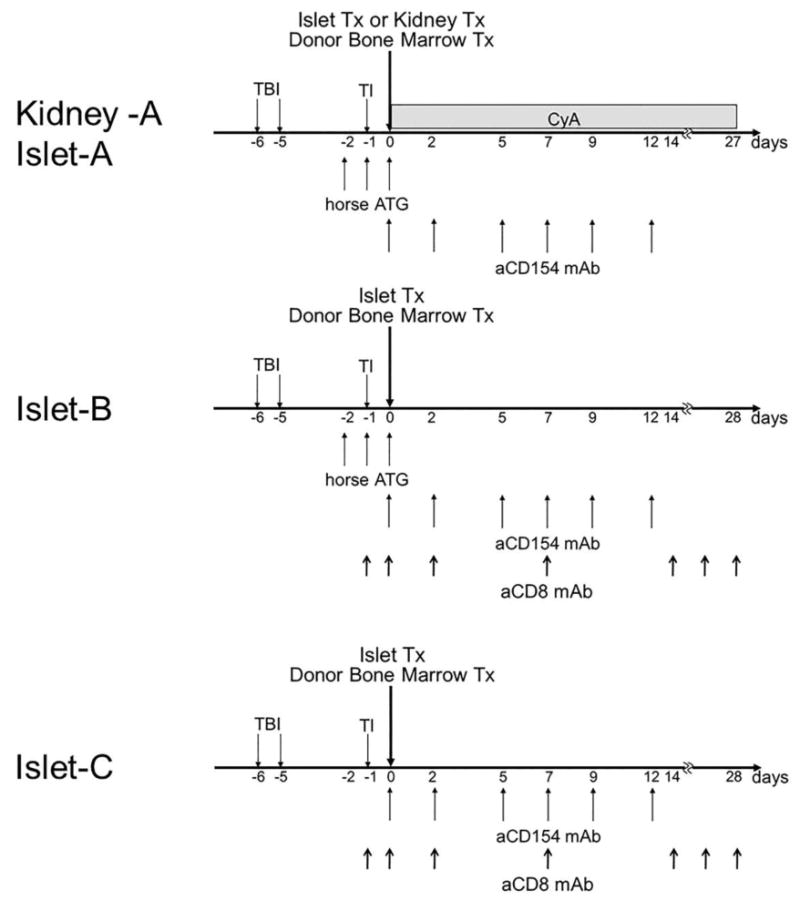

Conditioning regimens (Fig. 1 and Table 1)

Figure 1. Standard regimen of CIBMT or CKBMT.

The conditioning regimen for Islet-A and Kidney-A includes nonmyeloablative total body irradiation (TBI, 1.5 Gy × 2) on days −6 and −5, thymic irradiation (TI, 7 Gy) on day −1, horse ATG (50 mg/kg/day on days −2, −1, and 0) and anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody (20 mg/kg on days 0 and +2, and 10 mg/kg on days +5, +7, +9, and +12). The recipients underwent CKBMT or CIBMT on day 0 and were treated with a one-month course of cyclosporine (CyA) to maintain therapeutic serum levels (>250 ng/mL). In Islet B, CyA was replaced with anti-CD8 mAb at 5 mg/kg on days −1, 0 and +2 and continued at 1 mg/kg weekly until day 28. In Islet C, Atgam was removed from the Islet B regimen.

Table 1. Conditioning regimens in all CIBMT and CKBMT monkeys.

| Group | Tx | Animal | Conditioning | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| TBI | TI | ATG | aCD154 | aCD8 | CyA | |||

| Islet A | Islet & BM | M4399 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + |

| Islet & BM | M2100 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

| Islet & BM | M6201 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

|

| ||||||||

| Islet B | Islet & BM | M7401 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | + | - |

| Islet & BM | M3202 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | + | - | |

| Islet & BM | M5002 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | + | - | |

|

| ||||||||

| Islet C | Islet & BM | M902 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | - | + | + | - |

| Islet & BM | M1402 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | - | + | + | - | |

|

| ||||||||

| Kidney A | Kidney & BM | M5898 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + |

| Kidney & BM | M2800 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

| Kidney & BM | M1900 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

| Kidney & BM | M200 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

| Kidney & BM | M4498 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

| Kidney & BM | M5598 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

| Kidney & BM | M2198 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

| Kidney & BM | M300 | 1.5 × 2 | 7 | + | + | - | + | |

Islet-A: The original conditioning regimen for combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation (CKBMT) was initially used for the combined islet and bone marrow transplantation (CIBMT) recipients. The regimen consisted of nonmyeloablative total body irradiation (TBI, 1.5 Gy × 2) on days −6 and −5 (relative to the CIBMT), thymic irradiation (TI, 7 Gy) on day −1, horse ATG (Atgam, Pharmacia and Upjohn, Kalamazoo, MI) (50 mg/kg/day on days −2, −1, and 0) and anti-CD154 monoclonal antibody (aCD154 mAb, American Type Culture Collection) (20 mg/kg on days 0 and +2, and 10 mg/kg on days +5, +7, +9, and +12). The recipients underwent CIBMT on day 0 and were treated with a one-month course of intramuscularly administered cyclosporine (CyA) (Novartis, Basel, Switzerland) (tapered from an initial dose of 15 mg/kg/day) to maintain therapeutic serum levels (>250 ng/mL). CyA was discontinued on day 27 post-transplant, after which serum CyA levels typically became undetectable by day 60 (Fig. 1).

Islet B: CyA was replaced with anti-CD8 mAb (cM-T807 provided by Centocor Inc. Horsham, PA) at 5 mg/kg on days −1, 0 and +2 and continued at 1 mg/kg weekly until day 28 (Fig. 1).

Islet C: Atgam was removed from the Islet B regimen (Fig. 1).

Kidney-A: The results in Islet-A, Islet-B and Islet-C recipients were compared with historical observations in CKBMT recipients summarized here as Kidney-A. The conditioning regimen used for the CKBMT group was exactly the same as that administered for the Islet-A group (Fig. 1).

Induction and management diabetes

One week before transplantation, diabetes was induced with an intravenous injection of streptozotocin (STZ, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at a dose of 55 mg/kg (13). Blood glucose (BG) levels were then monitored two times per day and the diabetic monkeys were treated with NPH and regular insulin to maintain blood glucose levels of 80-300 mg/dl.

Isolation of donor pancreatic islets

Our method for islet isolation was reported in detail previously (18). Briefly, after being perfused with University of Wisconsin (UW) solution, the pancreas was digested with Liberase HI (Roche Biochmicals, Indianapolis, IN). The digested tissue was applied to a discontinuous gradient with Ficoll (Sigma Chemical. St. Louis, MO) at a ratio of 1:11 (tissue/Ficoll). Islets were then collected from the two interfaces, washed and counted for transplantation.

Pancreatic islet transplantation (PITx)

Under general anesthesia, a small midline celiotomy was made and a 22-gauge × 0.75 inch catheter was inserted into the inferior mesenteric vein. Alloislets were suspended in 10 ml of normal saline with 100 U/kg heparin and infused into the portal circulation through the venous cannula.

Kidney transplantation (KTx)

Monkeys underwent heterotopic renal transplantation and bilateral nephrectomies under anesthesia as previously described (2).

Donor derived Bone marrow transplantation (DBMT)

Bone marrow cells were harvested from the vertebral bones of the islet donor after euthanasia. Isolated bone marrow cells (3.0 × 108 mononuclear cells /kg) were infused intravenously.

Detection of chimerism

After standard water shock treatment, peripheral blood cells were first stained with donor-specific mAbs chosen from a panel of mouse anti-human HLA class I mAbs that cross-react with cynomolgus monkeys. Cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C, and then washed twice. Cell-bound mAb was detected with fluorescein isothiothianate (FITC)-conjugated rat anti-mouse immunoglobulin IgG2a mAb (Pharmingen, San Diego, CA), which was incubated for 30 min at 4°C, followed by two washes and analysis on FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). In all experiments, the percentage of cells that stained with each mAb was determined from one color fluorescence histogram and compared with those obtained from donor and pretreatment frozen recipient cells, which were used as positive and negative controls. The percentage of cells considered positive was determined with a cutoff chosen as the fluorescence level at the beginning of the positive peak for the positive control stain and by subtracting the percentage of cells stained with an isotype control. By using forward and 90° light scatter (FSC and SSC, respectively) dot plots, lymphocyte (FSC- and SSC-low), granulocyte (SSC-high), and monocyte (FSC-high but SSC-low) populations were gated, and chimerism was determined separately for each population. Nonviable cells were excluded by propidium iodide staining.

Cytokine measurement

Serum IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-17, IL-12 (P40) and IL-10 levels at 1 week (CIBMT; n=7, CKBMT; n=3) and 4 weeks (CIBMT; n=8, CKBMT; n=7) after transplantation were determined by Luminex (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) using Non-Human Primate Cytokine, PRCYTOMAG-40K (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA), following the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

All values are represented as mean ± S.D.. An intergroup statistical analysis was performed using Student's t or Welch's t tests. For chimerism an intergroup statistical analysis was performed using Bonferonni correction test. The differences were considered statistically significant when a p-value was less than 0.05. Graft survival was analyzed by Prism 4 (Graph Pad Software Inc. La Jolla, CA).

Results

A conditioning regimen that reliably induced mixed chimerism and renal allograft tolerance, failed to induce long-term islet allograft survival

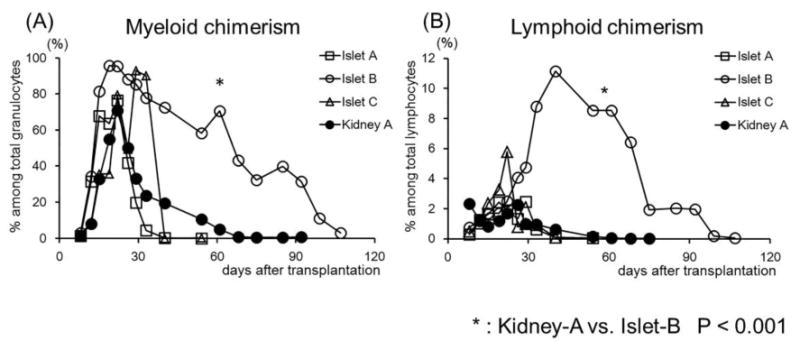

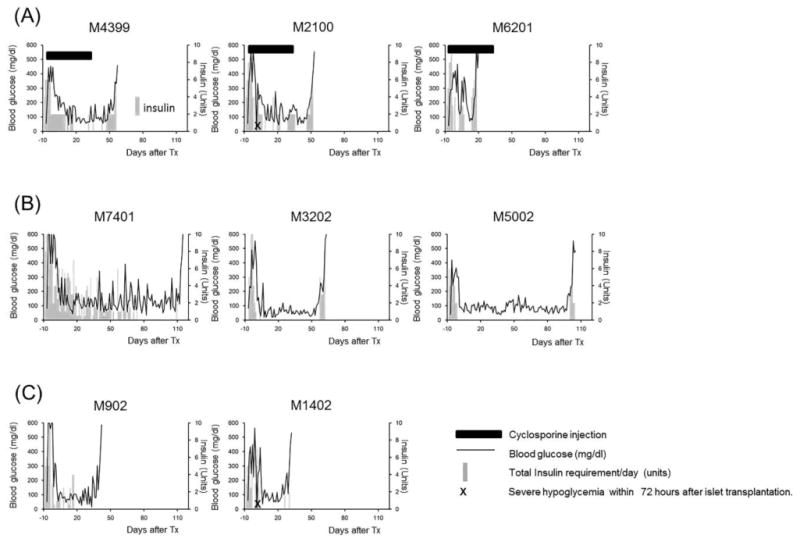

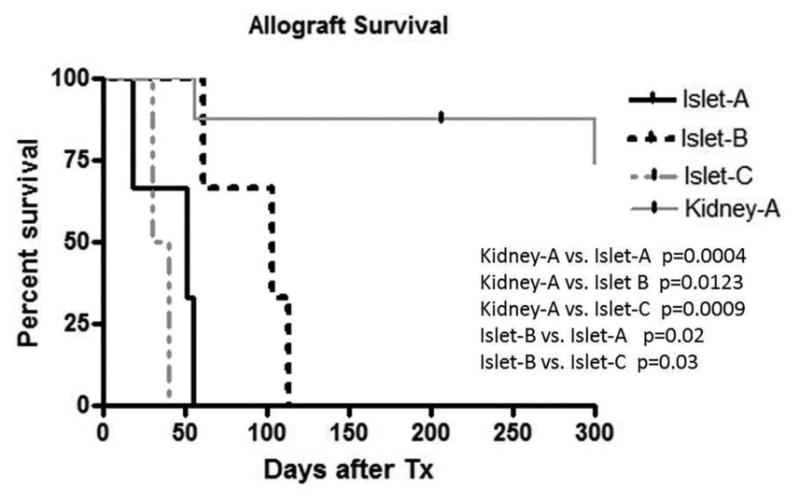

An average of approximately 50,000 IE of islets was isolated from a cynomolgus monkey pancreas with a purity and viability typically exceeding 90%, as detailed in Table 2. The final islet preparation had a mean insulin and DNA content of approximately 400 and 900 μg, respectively (18). A separate study has shown that islet allograft survival was 4 - 5 days without any immunosuppressive treatment (14). Three monkeys (M4399, M2100, and M6201) were treated with the Islet-A regimen, which reliably induced renal allograft tolerance in most CKBMT recipients (Kidney-A) (Table 1). With this regimen, all three islet recipients developed comparable levels of multilineage chimerism (Fig. 2). All recipients received a sufficient number of islets (>11000 IEQ/kg) with high purity and viability and transiently became insulin independent post-transplantation (Fig 3A). Nevertheless, all recipients in this group exhibited unstable islet function and failed to achieve long-term islet allograft survival (18, 51, and 55 days, p=0.0004 in Kidney-A vs. Islet-A) (Fig. 4).

Table 2. Clinical features of CIBMT and CKMBT recipients.

| Group | Animal | Graft | Chimerism | IEQ/kg | Purity | Viability | Graft Survivals (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Islet A | M4399 | Islet | + | 12321 | 95 | 90 | 55 |

| M2100 | Islet | + | 11285 | 91 | 95 | 51 | |

| M6201 | Islet | + | 14900 | 90 | 90 | 18 | |

|

| |||||||

| Islet B | M7401 | Islet | ++ | 19090 | 95 | 95 | 113 |

| M3202 | Islet | + | 13257 | 95 | 95 | 61 | |

| M5002 | Islet | ++ | 14443 | 90 | 80 | 103 | |

|

| |||||||

| Islet C | M902 | Islet | + | 11000 | 86 | 75 | 40 |

| M1402 | Islet | + | 13334 | 90 | 70 | 30 | |

|

| |||||||

| Kidney A | M5898 | Kidney | + | - | >2497 | ||

| M2800 | Kidney | + | - | >4115 | |||

| M1900 | Kidney | + | - | 837 | |||

| M200 | Kidney | + | - | >755 | |||

| M4498 | Kidney | + | - | 401 | |||

| M5598 | Kidney | + | - | 307 | |||

| M2198 | Kidney | + | - | >206 | |||

| M300 | Kidney | - | - | 56 | |||

Figure 2. Multilineage mixed hematopoietic chimerism after CIBMT and CKBMT.

Mean values of Chimerism (%) detected in both Myeloid (A) and Lymphoid (B) lineages in Islet-A, B, C, and Kidney-A recipients. In Islet-B, recipients developed significantly higher and longer duration multilineage chimerism than observed in the other groups.

Figure 3. Clinical courses after CIBMT.

Solid lines represent serum glucose levels. Gray bars indicate insulin requirements (unit) per day. Black bars indicate the duration of CyA therapy. X indicates severe hypoglycemic episode within 72 hours after islet transplantation.

Figure 4. Kidney and islet allograft survivals.

The kidney allograft survival was significantly longer than any islet allograft survival. Islet allograft survival in Islet-B was significantly longer than that in Islet-A or Islet-C.

A CNI-free regimen with anti-CD8 mAb significantly improved chimerism induction and prolonged islet allograft survival

Since the loss of islet function may be attributed to CNI toxicity of the islet allograft, we tested a CNI-free regimen in three recipients. Since our previous studies showed improved chimerism induction with more aggressive CD8+ memory T cell (TMEM) deletion (15), anti-CD8 mAb was added to the Kidney-A regimen in place of CyA (Islet-B). With this regimen, the levels and duration of chimerism were significantly improved in both lymphoid and myeloid lineages (Fig. 2). Islet allograft survival was also more stable and prolonged (p=0.02) comparing with Islet-A (Fig. 4). However, these recipients eventually lost islet allograft function due to rejection by day 113 (Figs. 3B, 5A and 5B) and allograft tolerance was not achieved. In Islet-C, in an attempt to develop a less invasive protocol, Atgam was also removed from the Islet-B regimen (Islet-C). The level of chimerism induced with this regimen was comparable with those observed in Islet-A (Fig. 2) but both recipients lost islet allograft function soon after discontinuation of immunosuppression (Figs. 3C and 4).

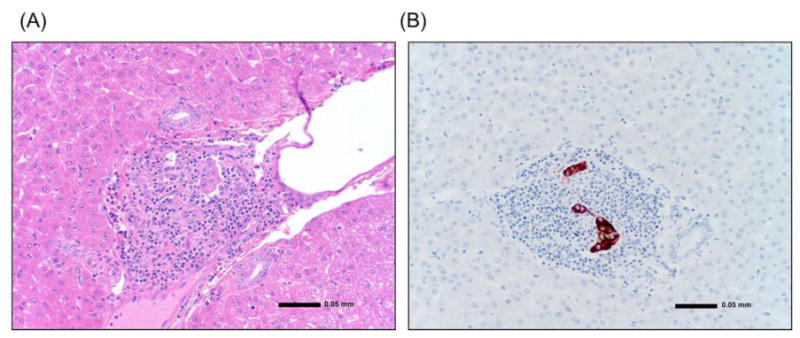

Figure 5. Histopathology of islet allograft.

(A) The Islet allograft in the liver (day 113). The liver was examined at autopsy. There was marked mononuclear cell infiltration in the islet allograft transplanted in the liver. (B) Insulin staining of islets (day 113). There was limited islet tissue remaining at the transplant site.

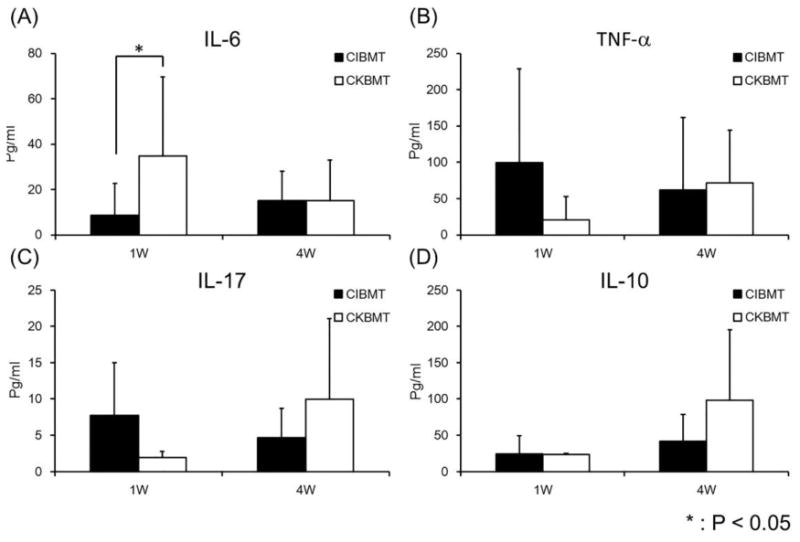

Serum cytokine levels in islet and kidney allograft recipients

Our previous studies on induction of renal allograft tolerance demonstrated that higher inflammatory responses prevented allograft tolerance induction (25). Thus, we postulated that failure of tolerance induction in islet transplantation could have been the result of higher inflammatory responses in the CIBMT recipients. Therefore, we assessed various serum cytokine levels measured following CIBMT versus CKBMT Significantly higher IL-6 levels (p<0.05) were observed at one week after kidney transplantation, compared with those observed in islet transplantation. On the other hand, TNF-α and IL-17 levels tended to be higher but not statistically significant in islet allograft recipients at one week. No significant difference was observed in any cytokines at 4 weeks after transplantation (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Inflammatory cytokine levels and IL-10 in the sera.

Black and white columns represent the serum cytokine levels in recipients of the islet allograft (CIBMT) and the kidney allograft (CKBMT) at 1 week (1W) and 4 weeks (4W) after transplantation. IL-6 level was significantly higher in recipients of the kidney allograft than those of islets at 1 week after transplantation (A). Although statistically not significant, TNF-α and IL-17 tended to be higher in islet recipients than those in kidney recipients at 1W after transplantation (B, C), and IL-10 has an opposite trend at 4W after transplantation (D).

Discussion

We have previously reported long-term renal allograft survival without ongoing immunosuppression administered in MHC-mismatched NHP recipients of CKBMT after treatment with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen (5,8,11). This approach has been successfully translated to HLA mismatched clinical kidney transplant recipients with the longest immunosuppression free survival now exceeding 12 years (6,9,10). In the NHP recipients, peripheral blood chimerism typically became undetectable by 30 to 60 days after transplantation (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, long-term survival of renal allograft was achieved without the need for chronic immunosuppression. In contrast to the renal allograft, our previous studies demonstrated that induction of heart allograft tolerance was not achievable after induction of transient chimerism (7). However, we recently observed that lung allograft tolerance is inducible even with transient chimerism (22). Therefore, tolerance induction via our approach with transient chimerism appears to be organ/tissue specific with kidney and lung allografts possibly having some mechanisms in common that maintain allograft tolerance after disappearance of chimerism. In a previous study, as an initial attempt to extend our approach to cellular transplantation was performed in a recipient already tolerant of a renal allograft. Two years after the CKBMT and withdrawal of immunosuppression, diabetes was induced with STZ and Islets harvested from the original Kidney/BM donor were transplanted into the portal circulation and beneath the kidney capsule (12). Euglycemia was achieved without additional immunosuppression. Although the recipient became diabetic 300 days after islet transplantation, viable transplanted islets were found in the liver and under the kidney capsule without any evidence of rejection. This study suggested that islet allograft tolerance could be achieved at least in a recipient already tolerant of a kidney allograft.

In the current study, we investigated whether tolerance of isolated islets, without the presence of a kidney allograft, could be similarly induced via the transient chimerism approach. Following conditioning with the same therapeutic regimen that consistently induces renal allograft tolerance, all three CIBMT recipients developed comparable levels of hematopoietic chimerism to those observed after CKBMT. However, none of the CIBMT recipients achieved prolonged islet allograft survival. One potential control for this group (Islet A) would have been the use of autografts to rule out islet loss due to non-immunologic causes, such as the toxicity of the conditioning regimen or nonspecific inflammatory responses. However, this control is practically difficult to perform, as a recipient has to tolerate a strenuous conditioning regimen immediately after near-total pancreatectomy. Therefore, to rule out the possibility of islet toxicity by CNI, rather than rejection, as the cause for these failures, we developed a CNI free conditioning regimen by substituting anti-CD8 mAb for CyA used in the first three recipients. The rational for utilizing anti-CD8 mAb was based on our previous observations that more effective CD8+ memory T cell depletion resulted in improved chimerism induction (15,25). As we expected, all anti-CD8 mAb treated recipients developed significantly higher levels of multilineage chimerism than that observed after Islet-A with CyA. Similar improvement of chimerism was not observed without Atgam (Islet-C), indicating that some intervention on CD4+ T cells by Atgam may also be important for chimerism induction. Although the anti-CD8 mAb treated recipients did achieve significantly longer allograft survival, tolerance was not induced with resumption of insulin administration being required in all recipients after several months.

The explanation for the contrasting results between CIBMT and CKBMT could be largely attributed to alloimmunity but the graft loss due to CNI toxicity and nonspecific inflammatory responses should also be taken into consideration. For example, insulin requirements after transplantation was higher in Islet-A than in CNI-free regimens (Islet-B and Islet C), suggesting that the toxicity of CNI on islet allografts is indeed concerning in post-transplant islet function. On the other hand, two (M2100 and M1402) recipients experienced undetectable hypoglycemia within 72 hours after CIBMT (Fig. 3, marked with X), which may indicate some islet cells of these recipients were destroyed by instant blood-mediated inflammatory reaction (IBMIR) (17,26). Interestingly, recipients of the kidney allograft did not lose their allograft function despite significantly higher serum IL-6 levels (Fig. 6), indicating that the kidney allograft may be able to tolerate inflammatory responses more than the islets (4,20).

The loss of islet function in three recipients in Islet-B may be attributed to the anti-donor alloimmune response. As observed in our previous study with isolated heart allografts, islet allografts were rejected after the loss of chimerism. These results may indicate that additional mechanisms may be necessary to maintain tolerance after the loss of chimerism in islet or heart transplantation. In our most recent study, we found that stable heart allograft tolerance can be induced even with transient chimerism if renal allograft from the same donor is simultaneously transplanted. The removal of the kidney allograft at one year after co-transplantation resulted in immediate rejection of heart allograft, indicating a critical role of the kidney allograft in maintenance of tolerance after the loss of chimerism (23). Therefore, co-transplantation of a kidney allograft with islet transplantation may be an attractive strategy. Different from heart transplantation, kidney and islet co-transplantation is more clinically applicable.

In conclusion, significant improvement of mixed chimerism induction and islet allograft survival were achieved without CNI by addition of anti-CD8 mAb. However, unlike the kidney allograft, islet allograft tolerance was not induced with transient chimerism. Induction of more durable mixed chimerism may be necessary for induction of islet allograft tolerance.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by POI-HL18646, ROI A137692-05, U19 AI102405-01.

Abbreviations

- CIBMT

combined islet and bone marrow transplantation

- CKBMT

combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation

- NHPs

nonhuman primates

- PITx

pancreatic islet transplantation

- STZ

streptozotocin

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the Cell Transplantation. This manuscript was also not prepared or funded by any commercial organization.

References

- 1.Bellin MD, Barton FB, Heitman A, Harmon JV, Kandaswamy R, Balamurugan AN, Sutherland DE, Alejandro R, Hering BJ. Potent induction immunotherapy promotes long-term insulin independence after islet transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1576–1583. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03977.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosimi AB, Delmonico FL, Wright JK, Wee SL, Preffer FI, Jolliffe LK, Colvin RB. Prolonged survival of nonhuman primate renal allograft recipients treated only with anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody. Surgery. 1990;108:406–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heisel O, Heisel R, Balshaw R, Keown P. New onset diabetes mellitus in patients receiving calcineurin inhibitors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:583–595. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-6143.2003.00372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanak MA, Takita M, Kunnathodi F, Lawrence MC, Levy MF, Naziruddin B. Inflammatory response in islet transplantation. Int J Endocrinol. 2014;30 doi: 10.1155/2014/451035. 451035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Colvin RB, Powelson J, Eason J, Kozlowski T, Sykes M, Monroy R, Tanaka M, Sachs DH. Mixed allogeneic chimerism and renal allograft tolerance in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 1995;59:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Spitzer TR, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Suthanthiran M, Saidman SL, Shaffer J, Preffer FI, Ding R, Sharma V, Fishman JA, Dey B, Ko DS, Hertl M, Goes NB, Wong W, Williams WW, Jr, Colvin RB, Sykes M, Sachs DH. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:353–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawai T, Cosimi AB, Wee SL, Houser S, Andrews D, Sogawa H, Phelan J, Boskovic S, Nadazdin O, Abrahamian G, Colvin RB, Sach DH, Madsen JC. Effect of mixed hematopoietic chimerism on cardiac allograft survival in cynomolgus monkeys. Transplantation. 2002;73:1757–1764. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200206150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawai T, Poncelet A, Sachs DH, Mauiyyedi S, Boskovic S, Wee SL, Ko DS, Bartholomew A, Kimikawa M, Hong HZ, Abrahamian G, Colvin RB, Cosimi AB. Long-term outcome and alloantibody production in a non-myeloablative regimen for induction of renal allograft tolerance. Transplantation. 1999;68:1767–1775. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199912150-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawai T, Sachs DH, Sprangers B, Spitzer TR, Saidman SL, Zorn E, Tolkoff-Rubin N, Preffer F, Crisalli K, Gao B, Wong W, Morris H, LoCascio SA, Sayre P, Shonts B, Williams WW, Jr, Smith RN, Colvin RB, Sykes M, Cosimi AB. Long-term results in recipients of combined HLA-mismatched kidney and bone marrow transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:1599–1611. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kawai T, Sachs DH, Sykes M, Cosimi AB. HLA-mismatched renal transplantation without maintenance immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1850–1852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1213779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai T, Sogawa H, Boskovic S, Abrahamian G, Smith RN, Wee SL, Andrews D, Nadazdin O, Koyama I, Sykes M, Winn HJ, Colvin RB, Sachs DH, Cosimi AB. CD154 blockade for induction of mixed chimerism and prolonged renal allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:1391–1398. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kawai T, Sogawa H, Koulmanda M, Smith RN, O'Neil JJ, Wee SL, Boskovic S, Sykes M, Colvin RB, Sachs DH, Auchincloss H, Jr, Cosimi AB, DS CK. Long-term islet allograft function in the absence of chronic immunosuppression: a case report of a nonhuman primate previously made tolerant to a renal allograft from the same donor. Transplantation. 2001;72:351–354. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107270-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koulmanda M, Qipo A, Chebrolu S, O'Neil J, Auchincloss H, Smith RN. The effect of low versus high dose of streptozotocin in cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascilularis) Am J Transplant. 2003;3:267–272. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koulmanda M, Qipo A, Fan Z, Smith N, Auchincloss H, Zheng XX, Strom TB. Prolonged survival of allogeneic islets in cynomolgus monkeys after short-term triple therapy. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1296–1302. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.03973.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koyama I, Nadazdin O, Boskovic S, Ochiai T, Smith RN, Sykes M, Sogawa H, Murakami T, Strom TB, Colvin RB, Sachs DH, Benichou G, Cosimi AB, Kawai T. Depletion of CD8 memory T cells for induction of tolerance of a previously transplanted kidney allograft. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1055–1061. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01703.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C, Noorchashm H, Sutter JA, Naji M, Prak EL, Boyer J, Green T, Rickels MR, Tomaszewski JE, Koeberlein B, Wang Z, Paessler ME, Velidedeoglu E, Rostami SY, Yu M, Barker CF, Naji A. B lymphocyte-directed immunotherapy promotes long-term islet allograft survival in nonhuman primates. Nat Med. 2007;13:1295–1298. doi: 10.1038/nm1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moberg L, Johansson H, Lukinius A, Berne C, Foss A, Kallen R, Ostraat O, Salmela K, Tibell A, Tufveson G, Elgue G, Nilsson Ekdahl K, Korsgren O, Nilsson B. Production of tissue factor by pancreatic islet cells as a trigger of detrimental thrombotic reactions in clinical islet transplantation. Lancet. 2002;360:2039–2045. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)12020-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Neil JJ, Tchipashvili V, Parent RJ, Ugochukwu O, Chandra G, Koulmanda M, Ko D, Kawai T. A simple and cost-effective method for the isolation of islets from nonhuman primates. Cell Transplant. 2003;12:883–890. doi: 10.3727/000000003771000110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ricordi C. The Path for Tolerance Permissive Immunomodulation in Islet Transplantation. Transplantation. 2014;23:23. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shapiro AM. Strategies toward single-donor islets of Langerhans transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2011;16:627–631. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0b013e32834cfb84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith RN, Kent SC, Nagle J, Selig M, Iafrate AJ, Najafian N, Hafler DA, Auchincloss H, Orban T, Cagliero E. Pathology of an islet transplant 2 years after transplantation: evidence for a nonimmunological loss. Transplantation. 2008;86:54–62. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318173a5da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tonsho M, Lee S, Aoyama A, Boskovic S, Nadazdin O, Capetta K, Smith RN, Colvin RB, Sachs DH, Cosimi AB, Kawai T, Madsen JC, Benichou G, Allan JS. Tolerance of Lung Allografts Achieved in Nonhuman Primates via Mixed Hematopoietic Chimerism. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2231–2239. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonsho M, M T, Klarin D, Boskovic S, Nadazdin O, Benichou G, Cosimi AB, Smith NR, Colvin RB, Kawai T, Madsen JC. Successful tolerance induction of cardiac allografts in nonhuman primates through donor kidney co-transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2012;13(Suppl 5):181–182. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vendrame F, Pileggi A, Laughlin E, Allende G, Martin-Pagola A, Molano RD, Diamantopoulos S, Standifer N, Geubtner K, Falk BA, Ichii H, Takahashi H, Snowhite I, Chen Z, Mendez A, Chen L, Sageshima J, Ruiz P, Ciancio G, Ricordi C, Reijonen H, Nepom GT, Burke GW, 3rd, Pugliese A. Recurrence of type 1 diabetes after simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation, despite immunosuppression, is associated with autoantibodies and pathogenic autoreactive CD4 T-cells. Diabetes. 2010;59:947–957. doi: 10.2337/db09-0498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada Y, Boskovic S, Aoyama A, Murakami T, Putheti P, Smith RN, Ochiai T, Nadazdin O, Koyama I, Boenisch O, Najafian N, Bhasin MK, Colvin RB, Madsen JC, Strom TB, Sachs DH, Benichou G, Cosimi AB, Kawai T. Overcoming memory T-cell responses for induction of delayed tolerance in nonhuman primates. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:330–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03795.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin D, Ding JW, Shen J, Ma L, Hara M, Chong AS. Liver ischemia contributes to early islet failure following intraportal transplantation: benefits of liver ischemic-preconditioning. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:60–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]