Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the feasibility of aortic 4D flow MRI at 7T with improved spatial resolution using kt-GRAPPA acceleration while restricting acquisition time and to address RF excitation heterogeneities with B1+ shimming.

Materials and Methods

4D flow MRI data were obtained in the aorta of 8 subjects using a 16-channel transmit/receive coil array at 7T. Flow quantification and acquisition time were compared for a kt-GRAPPA accelerated (R=5) and a standard GRAPPA (R=2) accelerated protocol. The impact of different dynamic B1+ shimming strategies on flow quantification was investigated. Two kt-GRAPPA accelerated protocols with 1.2x1.2x1.2mm3 and 1.8x1.8x2.4mm3 spatial resolution were compared.

Results

Using kt-GRAPPA, we achieved a 4.3 fold reduction in net acquisition time resulting in scan times of about 10 minutes. No significant effect on flow quantification was observed compared to standard GRAPPA with R=2. Optimizing the B1+ fields for the aorta impacted significantly (p<0.05) the flow quantification while specific B1+ setting were required for respiration navigators. The high resolution protocol yielded similar flow quantification, but allowed the depiction of branching vessels.

Conclusion

7T in combination with B1+ shimming allows for high-resolution 4D flow MRI acquisitions in the human aorta while kt-GRAPPA limits total scan times using without affecting flow quantification.

Introduction

Time-resolved 3D gradient echo-based (GRE) phase-contrast (PC) imaging with three-directional velocity encoding, often termed “4D flow MRI” is a technique that provides quantitative information about the time-resolved velocity vector field of the human blood flow with 3D coverage of the region of interest (1–4). In the human aorta, 4D flow MRI has been utilized to investigate changes in hemodynamics associated with aortic pathologies such as aortic valve disease, aneurysms, or dissections (4–13). 4D flow MR imaging may provide important hemodynamic information that could be used to follow disease progression, monitor treatment and help making therapeutic decisions (14).

The application of 4D flow MRI in clinical routine, however, is still hindered by long acquisition times of 10–20 minutes for scans targeting the thoracic aorta and by its limited spatial resolution of 2–3 mm in each dimension, often acquired anisotropically (1). In general, higher spatiotemporal resolution is desired in order to reduce partial volume effects and temporal blurring, which may bias measured hemodynamic parameters. However, increasing the resolution extends acquisition times and requires a sufficiently high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), thus, in practice a tradeoff between spatiotemporal resolution, SNR and scan time needs to be found.

The acquisition time is typically reduced by applying parallel imaging. Utilizing coils with higher number of receive channels allows increasing the parallel imaging acceleration factors without impacting flow quantification (15). Also, non-Cartesian acquisition techniques such as PC-VIPR have been successfully applied resulting in scan times below 10 minutes (16). Further shortening of the acquisition time can be achieved by accelerating along the spatial and temporal dimension using kt-BLAST, kt-SENSE and kt-GRAPPA (17–19), or by applying compressed sensing techniques (20–22). Applying both temporal and spatial acceleration is a promising route to achieve short total acquisition time while pushing towards higher resolution. In order to achieve higher SNR, an increasing number of acquisitions are now conducted at 3 T (rather than at 1.5 T), based on the promises of 2.5-fold SNR increase realized in phantoms (23) and of 1.5 to 2-fold SNR increase demonstrated in vivo (24,25), in comparison to 1.5 T acquisitions. An additional 2.2 to 2.6-fold improvement in SNR has recently been reported in initial 4D flow studies performed at ultra-high field (UHF) operating at 7 T (25,26). This gain in SNR was used by van Ooij et al. (26) to increase the spatial resolution in the brain up to (0.5 mm)3 and, in comparison to 3 T, the authors found improved segmentations of smaller vessels in the Circle of Willis, lower velocity vector magnitudes due to reduced noise bias, larger vessel areas properly detected and smoother streamlines. Berg et al. (27) used 4D flow MRI to study intracranial aneurysms in comparison to computational fluid dynamics at a resolution of 0.75x0.75x0.8mm3, and reported better representations of the vascular details at 7 T compared to 3 T. To the authors’ knowledge, the work by Hess et al. (25) is the only study that applied 4D flow MRI to the human body at 7 T so far, with spatial resolution of 2x2x2.4 mm3. The aim of that study was to investigate the increase in SNR for aortic 4D flow MRI compared to 1.5T and 3T with and without administration of contrast media.

As illustrated by Hess et al. and in other studies (25,28–31) human body imaging at 7 T is challenging, in large part because of the shorter wavelength of the transmit B1 (B1+) and receive B1 (B1−). The associated spatial flip angle variations in the body are typically addressed using multi-channel transmit coils in combination with either B1+ shimming (28) or parallel transmission techniques (30,32) to achieve uniform flip angles. Other approaches such as TIAMO (29) aim at achieving contrast uniformity by combining multiple acquisitions with different excitation patterns. To reduce spatial B1+ variations in 4D flow MRI at 7T, Hess et al. (25) utilized a dynamic shimming technique, which was first introduced in the body at 7T by Metzger et al (28) and which is also used in the present work. This approach applies different shim settings optimized for separate regions of interest (ROI), represented here by the aorta and the diaphragm.

The aim of this work is to investigate the feasibility of increasing spatial resolution while maintaining short acquisition times using 7T 4D flow MRI in combination with kt-GRAPPA acceleration in the human aorta. The impact of different B1+ shim settings on spatiotemporally resolved flow quantification is investigated.

Methods

System and Setup

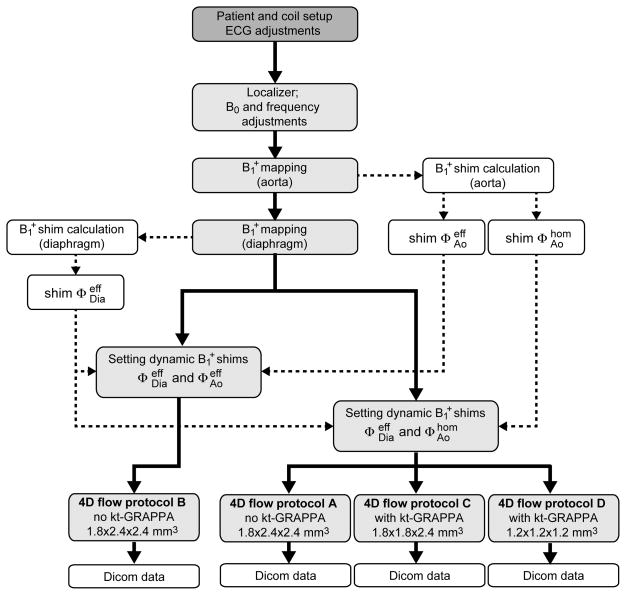

All experiments were performed on a whole body 7 T system (Magnetom 7T, Siemens Medical Solution, Erlangen, Germany) equipped with a B1+ shimming system (CPC, Hauppauge, NY, USA). A 16-channel transmit/receive body coil array (33) was utilized, which is divided into a posterior and an anterior array consisting each of eight 16 cm long microstrip elements. Eight healthy subjects (age: 36.9±18.0 years, 4 female, 4 male), who provided written informed consent based on a study protocol approved by the local Institutional Review Board, participated in the study. A three-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) was attached to the subject’s chest. Because a robust detection of the cycle is challenging due to the strong magneto-hydrodynamic effect at UHF, the electrodes were repositioned prior to scanning until the cardiac cycle was properly detected. The total setup time including tuning/matching the RF coil and properly setting up the ECG varied between 20 and 40 minutes. The subsequent workflow of this study is summarized as a flowchart in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart diagram illustrating the workflow of the study.

4D flow sequence

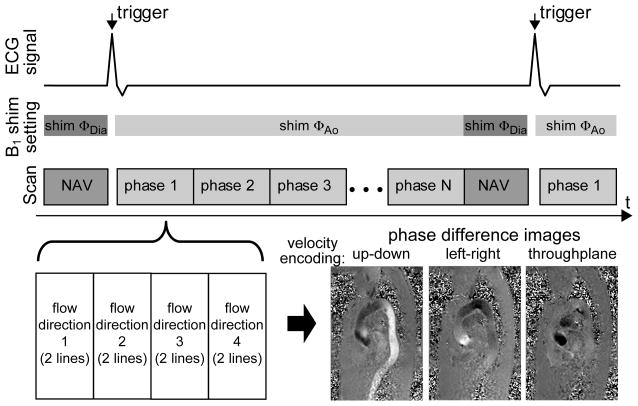

A 4D flow sequence, described in more detail in (1), was applied in a sagittal-oblique orientation to spatiotemporally resolve the blood velocity vector in three dimensions using a balanced four-point velocity encoding scheme with a maximum encoding velocity (venc) of 150 cm/s. This encoding scheme utilizes four time-resolved gradient-echo acquisitions with a fixed velocity encoding gradient magnitude on all three axes while different combinations of gradient polarities are applied on the three axes for each of the acquisition. The three spatially resolved velocity vector components vx(r,t), vy(r,t) and vz(r,t) are finally obtained by linear combinations of the phase images of all four acquisitions. As illustrated in Figure 2, within each cardiac cycle, which is divided into N cardiac phases, two k-space lines were acquired per cardiac phase resulting in temporal resolutions of 38.4ms – 40.8ms (Table 1). To reduce respiration induced motion artifacts, a navigator scan consisting of a pair of 90° and 180° RF pulses was applied once during the cardiac cycle. Based on the position of the diaphragm derived from the navigator scan an acceptance window was determined to reject or include subsequently acquired 4D flow data for image reconstruction.

Figure 2.

Acquisition scheme for the applied 4D flow sequence scan. The B1+ shim setting is switched before and after the navigator scan (NAV) toggeling between settings ΦAo and ΦDia using a TTL signal sent by the MR scanner. A 4-point velocity encoding scheme is applied for the 4D flow acquisition, which acquires for each cardiac cycle 2 k-space lines per encoding direction and per cardiac phase (bottom left). The resulting phase difference images for the resulting 3 directions are illustrated in the bottom right image (here no post-processing such as eddy current correction or noise filtering applied).

Table 1.

Acquisition parameters for the four different 4D flow acquisitions used in this study.

| Protocol A | Protocol B | Protocol C | Protocol D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1+ shim solution | and | and | and * | and |

| Subjects | 1–8 | 3–8 | 1–8 | 1 and 8 |

| Resolution | 1.8x2.4x2.4mm3 | 1.8x1.8x2.4mm3 | 1.2mm isotropic | |

| FOV | 340x233x77mm3 | 340x191x48mm3 | ||

| TR/TE | 38.4ms/2.33ms | 40.8ms/2.5ms | ||

| Average TA (min:sec) | 16:48 | 10:56 | Subject 1: 18:18 Subject 8: 23:10 |

|

| Bandwidth | 449 Hz/Px | 445 Hz/Px | ||

| Acceleration method | GRAPPA | kt-GRAPPA | ||

| Acceleration factor | 2 | 5 | ||

| Phases | Minimum: 16; Maximum: 29; Average: 21 | Subject 1: 21, Subject 8: 21 | ||

| Heartrate [beats per minute] | Minimum: 59; Maximum: 102; Average:68 | Subject 1: 60 Subject 8: 60 |

||

| Navigator acceptance rate | Minimum: 38% Maximum: 99% Average: 75% | Subject 1: 65% Subject 8: 48% |

||

| Navigator acceptance Window | +/− 6mm | +/− 3mm | ||

| Slice Tracking Factor | 0.6 | |||

in subject 1 a static B1+ shim solution needed to be applied, which was a tradeoff between high efficiency in the diaphragm and low heterogeneity within the aorta.

B1+ mapping and B1+ shimming

In order to obtain optimized B1+ distributions for both the navigator scan (centered on the diaphragm) and the 4D flow scan (centered on the aorta), two independent B1+ shim solutions were dynamically applied throughout the sequence as described by Metzger et al (28). The first B1+ shim setting was optimized for the navigator scan and the second for the aortic 4D flow acquisition. Therefore, two single-slice B1+ mapping scans were performed: the first in an axial orientation targeting the diaphragm dome and the second in a sagittal-oblique orientation following the ascending aorta (AAo), the arch and descending aorta (DAo). The complex transmit sensitivity profiles were obtained for each transmit (TX) channel k utilizing a fast estimation technique (34), which acquires 16 GRE images of the same slice under end-expiratory breath-hold, with only one TX channel being active per image. Scan parameters were as follows: FOV = 400x225mm2, slice thickness = 8 mm, TR/TE = 2.6ms/1.2ms, resolution = 3.1x3.1x8 mm3, nominal flip angle (FA) = 10°.

Two regions of interest (ROI), ROIDIA and ROIAo were manually drawn, one on the axial image covering NDia voxels within the liver and one on the sagittal-oblique image covering NAo voxels within AAo, Arch and DAo (see Figure 3a). Subsequently, the resulting B1+ field, obtained by superposition of the 16 transmit channels, was optimized separately for the two distinct ROIs by modulating the transmit phase set Φ = {ϕ1,ϕ2,…, ϕ16} of the 16 transmit channels using the B1+ shimming unit.

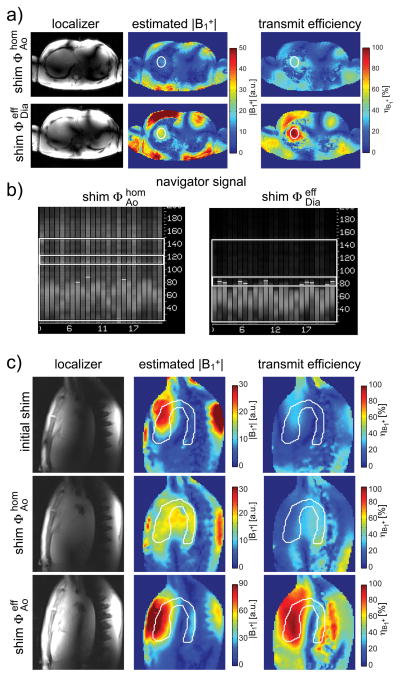

Figure 3.

a+b) Impact of the B1+ shim setting on the navigator signal. When setting (upper row) optimized for the aorta is also applied for the navigator scan, a low average B1+ efficiency of 37.0% is obtained within ROIDia targeting the diaphragm dome. The resulting poor detection of the diaphragm prohibits successful scanning (subfigure (b), left image). Switching to B1+ shim increases the average B1+ magnitude by a factor 2.4 (middle column) yielding an efficiency value of 87.7%. A clear delineation between lung and diaphragm is visible in navigator signal (subfigure (b), right image). The white circles in (a) indicate the region of interest used for B1+ shimming c) Estimated B1+ magnitude (middle column) and transmit efficiency (right column) for the initial, non-optimized B1+ shim setting and for the B1+ shim settings and , which were optimized over white region of interest. Note the different color scale for the efficient B1+ shim solution in the middle column. The left column illustrates localizer images obtained with the respective B1+ shim settings. Localizer images are not corrected for receive profiles.

Therefore, the transmit efficiency (35,36) being a measure of the constructive B1+ interference of the 16 TX channels, with , was evaluated:

| [1] |

with

| [2] |

The optimization was performed separately for each ROIs to maximize the mean transmit efficiency within each region 1

| [3] |

returning the optimized B1+ efficient phase set Φeff:

| [4] |

Here, r∈ROIDia, and N=NDia when the efficient shim setting for the navigator scan denoted by is calculated, while r∈ROIAo, and N=NAo when the efficient shim for the 4D flow scan is obtained.

Efficient B1+ shim solutions optimized over larger ROIs such as for shim tend to result in high spatial B1+ inhomogeneity values, which can be quantified by the coefficient of variation (CV), i.e. the standard deviation divided by the mean of ||ABT (r)||2 within the ROI. To evaluate the impact of an efficient in comparison to a homogeneous B1+ shim setting on flow quantification, a third B1+ shim setting, , was calculated that minimized the CV within ROIAo:

| [5] |

with

| [6] |

It should be noted that while efficient shim settings optimized over large regions tend to result in inhomogeneous B1+ distributions, homogeneous solutions calculated for the same ROI in turn result in low values (35), thus in lower flip angles if the transmit power is unchanged. All calculations were performed in Matlab (The Mathworks, Nattick, MA, USA).

The optimized B1+ fields were analyzed qualitatively by identifying the presence of local B1+ drops and quantitatively by calculating CV and .

Protocols

The 4D flow sequence was applied in four different protocols (protocols A–D) using various resolution settings, B1+ shim solutions and acceleration factors. Sequence parameters and details for the four different protocols are listed in Table 1. Protocol A served as the reference using a resolution of 1.8x2.4x2.4 mm3, a spatial coverage of 340x233x77mm3 and standard GRAPPA parallel imaging (37) with an acceleration factor of R=2. Further imaging parameters are listed in Table 1. This protocol was applied in all 8 subjects using dynamic B1+ shimming with and . Protocol B was identical to A, except that dynamic B1+ shimming with and was applied. This protocol was applied in subjects 3–8. In protocol C, the acceleration factor was increased to R=5 by utilizing kt-GRAPPA and the matrix size in phase-encoding direction was increased to achieve a resolution of 1.8x1.8x2.4mm3. The protocol was applied in all 8 subjects and except for subject 1 dynamic B1+ shimming was applied using shims and . In subject 1, static B1+ shimming needed to be applied, because dynamic switching of the B1+ shim sets was not yet implemented into the kt-GRAPPA sequence. Therefore, a joint optimization similar to slab selective B1+ shimming with multiple calibration slices (35) was performed targeting simultaneously the aorta and the diaphragm. The solution traded between low CV and high within ROIDia and ROIAo similar to (28). In Protocol D the spatial resolution was further increased to 1.2x1.2x1.2mm3. To limit the acquisition time kt-GRAPPA with R=5 was applied and the spatial coverage was reduced to 340x191x48mm3. This protocol was applied only in subjects 8 and 1, the latter subject participated a second time at the end of this study. In both cases dynamic B1+ shimming toggling between and was utilized.

kt-GRAPPA

Protocols C and D were performed using acceleration along the temporal and spatial dimension by applying PEAK-GRAPPA (38), an extension of kt-GRAPPA (19). Since high acceleration factors can lead to temporal blurring, we utilized an acceleration factor of R=5, which has shown to not significantly alter the resulting net flow, peak velocity, and time-resolved flow rates according to a recent study performed at 3T (39). In our study, spatial and temporal undersampling was performed along the dimensions ky, kz and t (auto-calibration signal lines Nky/Nkz = 20/8). The applied acceleration of R=5 resulted in a net-acceleration Rnet=4.3 and 4.5 for the two protocols. Further details of the implementation of kt-GRAPPA and an illustration of the applied k-space acquisition scheme can be found in (39).

Power limits and SAR calculation

The RF power was supervised on a per-channel basis by an in-house developed 16-channel monitoring system, which measured the forwarded and reflected RF power per channel in real time. Following the IEC guidelines (International Standard IEC 60601-2-33 2010) real-time RF power is averaged over a 10-second and a 6-minute window. To limit global SAR and 10g average local SAR maximum power limits were set to 4W and 2W per channel for the 10-second and 6-minute time averaged power values. These conservative limits were set identical to our previous cardiac study, which were derived for the same 16 channel transceiver coil from Electromagnetic (EM) simulations using the “Duke” body model (IT’IS Foundation, Zurich, Switzerland; http://www.itis.ethz.ch/news-events/news/virtual-population/enhanced-virtual-family-models-ella-duke-billie-thelonious/) while using the worst case from a large range of B1+ shimming solutions (30).

Post-Processing and statistical analysis

The acquired 4D flow data were post-processed using custom software written in Matlab (The MathWorks Inc., USA), as previously described (40). Residual spatially varying phases in the velocity data typically caused by eddy currents are estimated by a linear fit over static regions of the body and removed from the velocity data (41). Regions of high noise, such as the lungs, are detected by a noise and a standard-deviation filter and excluded for further post-processing (41). Velocity aliasing was corrected by unwrapping the phase-data and finally a 3D PC-MR angiogram (MRA) was calculated (40). Based on the PC-MRA data a 3D mask of the thoracic aorta geometry was created for each subject using 3D segmentation software (MIMICS, Materialise Inc., Belgium). For each subject, a mask M, which included the aortic root, AAo, arch and DAo, was first generated based on the homogeneous B1+ shim data (protocol A). This mask M was then overlaid in 3D with the velocity data of the efficient B1+ shim and the kt-GRAPPA acquisition (protocols B and C) to check for inter-scan motion. If motion was negligible mask M was also applied to 4D flow data obtained with protocols B and C; otherwise a new mask was generated based on the actual dataset.

Both the segmented aorta geometry and the 4D flow velocity data were imported into commercial software (Ensight, CEI, Inc. Apex, NC) for 3D blood flow visualization and quantification. Five planes were placed orthogonal to the aorta at the following locations: i) the aortic root, ii) the AAo, iii) the aortic arch, iv) the proximal descending aorta (pDAo) and v) the distal descending aorta (dDAo). For each plane, the temporally resolved volume flow rates (Q) through the planes, the net volume flow rate per cardiac cycle (Q̄) and time resolved peak velocity (vmax) within each plane were quantified.

For each of the 5 locations, differences of means in net flow between the acquisitions obtained with and as well as between kt-GRAPPA and standard GRAPPA acquisition were tested using a paired t-test. Normalcy was ensured using an Anderson-Darling test. The statistical analysis was performed in Matlab and values of p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

B1+ shimming for navigator acquisition targeting the diaphragm

Figures 3a+b illustrate the impact of applying independent B1+ shim settings for the navigator scan in one representative subject (subject 1). First, when B1+ shim setting , which was optimized to obtain homogeneous excitation within the aorta, was also applied to the navigator RF pulse targeting the diaphragm (Figure 3a), a low average transmit efficiency value of was obtained within ROIDia. This resulted in insufficient B1+ magnitude for the navigator pulses to detect the respiratory position based on the air-lung boundary as shown in Figure 3b (left column). The low transmit efficiency could not be compensated by increasing the RF voltage due to SAR and peak power limitations. The detection was improved by applying the B1+ shim setting to the navigator RF pulse, which elevated to 87.7%, resulting in a 2.4 times higher B1+ magnitude compared to setting (Figure 3b, right).

B1+ shimming for image acquisition targeting the aorta

The impact of B1+ shimming on the image acquisition targeting the aorta is illustrated in a representative case (subject 8) in Figure 3c. Compared to the initial, non-optimized B1+ shim setting (top row) the CV value was significantly reduced from 67.1% to 10.2% when using the homogeneous B1+ shim as applied in protocol A (see Figure 3c, middle row) with values ranging between 9.3% in the frontal AAo and 55.3% within the pDAo. Applying the efficient B1+ shim solution as in protocol B (Figure 3c, bottom row) increased from 27.6% to 73.8%, but to the cost of sharp local drops, particularly in the distal arch and pDAo. This pattern was observed in 5 out of 8 volunteers, particularly pronounced in subject 6 with a local value of 3.4% within pDAo. In subjects 4, 5 and 7, the efficient B1+ shim solution resulted in a complementary pattern with high values in the center and decreased towards the chest and spine. In all subjects, the efficiency variations observed with caused substantial fluctuations of B1+ across the target region resulting in 4.2 times higher CV values on average compared to shim . Details for all B1+ shim settings are listed in Supporting Table S1.

Static versus dynamic B1+ shimming

In contrast to all other acquisitions, which applied dynamic B1+ shimming with either and (protocols A, C, D) or and (protocol B), in subject 1 a static tradeoff B1+ shim solution needed to be applied in protocol C for both navigator and imaging scan. This resulted in reduced contrast of the navigator signal due to a reduction in from 87.7% to 58.2% within ROIDia (see Supporting Figure S2). Although this approach allowed for a successful acquisition, the navigator acceptance rate (i.e. the percentage of data used for reconstruction of all acquired data) was reduced from 74% using dynamic B1+ shimming to 53% using the static tradeoff B1+ shim. CV values for this tradeoff B1+ shim solution quantified in ROIAo were 12.1%, thus 2.7% higher than the average CV values for dynamic B1+ shimming (compare Supporting Table S1, middle column). Values for navigator acceptance rate and heart-rate are summarized in Table 1.

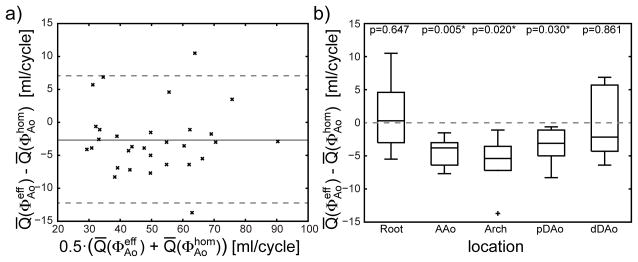

Flow quantification using homogeneous and efficient shims

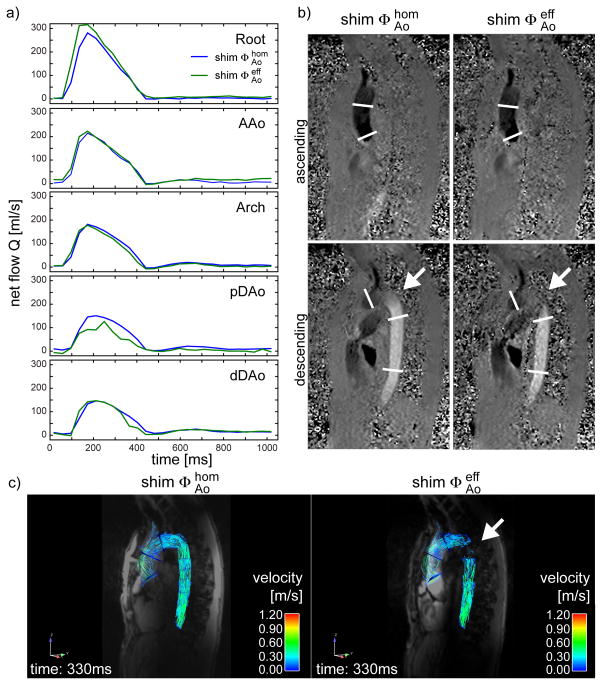

Flow rate values Q were quantified for protocols A and B and compared for subjects 3–8 for each plane and each phase of the cardiac cycle. Corresponding net flow rate values Q̄ calculated over the entire cycle are illustrated in a Bland-Altman diagram in Figure 4a. Details are listed in Supporting Table S3. The mean difference value averaged over all locations and all subjects was −2.6 ml/cycle with a SD of 5.0 ml/cycle. The spatially resolved flow rate differences for the five locations are illustrated in a boxplot in Figure 4b. Significantly lower flow rates (p<0.05) were found in AAo, Arch and DAo obtained with shim (protocol B) compared to (protocol A) with difference values (mean ± SD) of (−4.4±2.8) ml/cycle, (−6.1±4.4) ml/cycle and (−3.6±2.4) ml/cycle in these locations. Figure 5a illustrates the impact of both B1+ shim solutions on the quantification of Q in subject 6 for the five different locations. In this subject, a higher peak flow rate was observed in the aortic root, but pronounced distortion of the flow rate curve was observed particularly within pDAo. These effects are in line with increased noise in the phase difference images, visible in Figure 5b particularly between Arch and pDAo (see arrow). As illustrated in Figure 5c, the B1+ shim setting also affects the particle traces shown as pathlines during early diastole, which are disconnected in the distal arch.

Figure 4.

a) Bland-Altman plot illustrating differences between mean flow rate Q̄ obtained with the homogeneous B1+ shim and the efficient B1+ shim . The solid line illustrates the mean value of −2.6 ml/cycle and the dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval. b) Differences in flow quantification illustrated as boxplots for subjects 1–8 for the two B1+ shimming solutions grouped by the location of the quantification plane. p values obtained from paired t-test under null-hypothesis are listed above the plot and values below 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Figure 5.

Net flow Q as a function of the cardiac cycle for B1+ shim setting and n subject 6 obtained at 5 different locations of the thoracic aorta, which are indicated by white lines in subfigure (b). b) Uncorrected, non-filtered phase difference images for the ascending and descending aorta with head-feet flow encoding direction obtained with both B1+ shim solutions. The white arrow indicates a region of low B1+ prohibiting correct quantification of the velocity when using B1+ shim solution . c) Pathline images generated from the datasets obtained with and . The right image shows disconnected pathlines in the pDAo (arrow).

Comparison between standard Grappa (R=2) and kt-Grappa (R=5)

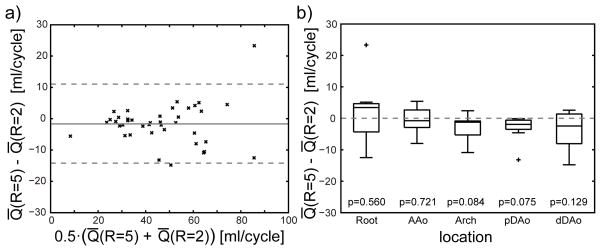

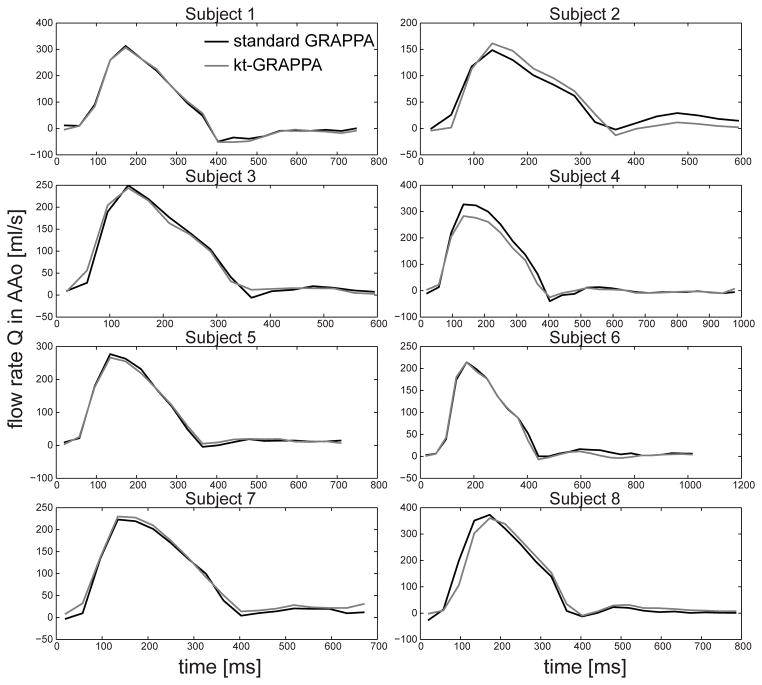

Differences in net flow rates Q̄ were quantified for both acceleration methods with shim setting , the standard GRAPPA with R=2 (protocol A) and kt-GRAPPA with R=5 (protocol C. Corresponding results are listed in Table 3 and illustrated in a Bland-Altman plot in Figure 6a. The mean difference value ± SD averaged over all subjects and locations amounted to (−1.6±6.5) ml/cycle. No significant difference in Q̄ was observed for the five different locations within the Aorta as shown in Figure 6b. For each of the eight subjects, the flow rates Q as a function of the cardiac cycle are illustrated exemplarily for the AAo in Figure 7. Qualitatively, similar flow curves can be observed for the two acceleration methods.

Figure 6.

a) Bland-Altman plot illustrating differences between mean flow rates Q̄ obtained with standard GRAPPA (R=2) and kt-GRAPPA (R=5). The solid line illustrates the mean value of −1.6 ml/cycle and the dashed lines indicate the 95% confidence interval. b) Flow quantification differences illustrated as boxplots for subjects 1–8 grouped by the location of the quantification plane. A paired t-test under null-hypothesis found no statistical significant differences (p>0.05).

Figure 7.

Flow rates Q as a function of the cardiac cycle calculated from standard GRAPPA acquisition (R=2) the kT-GRAPPA acquisition (R=5) within a plane located in the AAo.

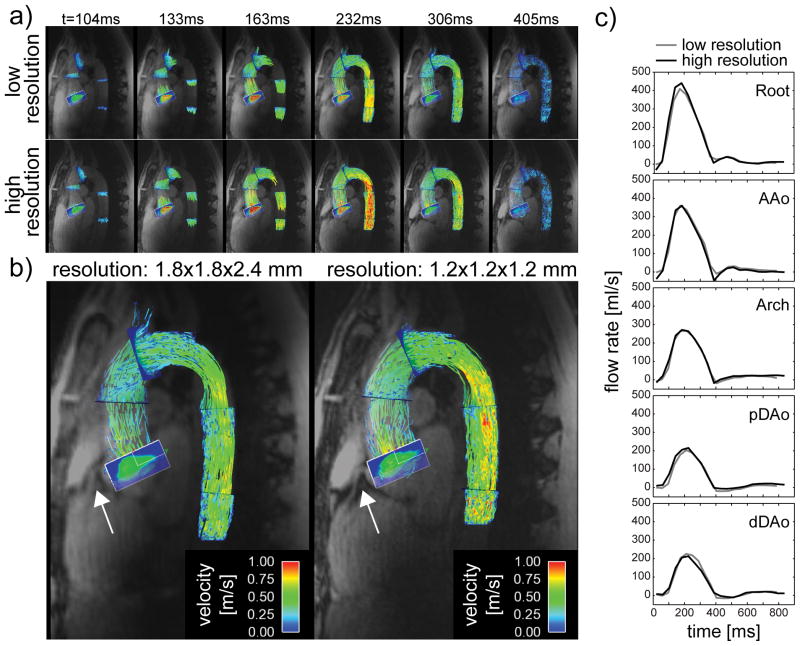

High resolution 4D flow acquisition

Figures 8a+b visualize pathlines fused with magnitude images for different time points of the cardiac cycle derived from protocols C and D. Due to the higher resolution, a 2.9 fold reduction in SNR was measured in the magnitude images on average. Corresponding time-resolved plots of the net flow rates quantified in the 5 planes are shown in Figure 8b. Similar pathline pattern and net flow curves were observed between the two acquisitions. The strongest difference in Q̄ between the high and the low resolution acquisition was calculated for pDAo with 9.6 ml/cycle. As can be seen in the gray scale component of the magnitude images in Figure 8b, more details in anatomical features, including the right coronary artery (white arrow), were depicted in the high resolution dataset in both subjects.

Figure 8.

a) Visualization of the blood velocity by pathlines for different time points of the cardiac cycle obtained with the low resolution (1.8x1.8x2.4 mm3) and the high resolution (1.2mm isotropic) dataset. b) The underlying magnitude images reveal a higher level of anatomical details such as the coronary root as highlighted by the white arrow. c) Flow rates Q for different segments of the thoracic aorta as a function of the cardiac cycle derived from the low-resolution and the high resolution dataset.

Discussion

The need for higher spatiotemporal resolution in 4D flow MRI is frequently discussed in literature (1,5,42,43). Velocity values and particularly peak velocities occurring during systole can be underestimated when measured with 4D flow MRI in comparison to ultrasound (42), which can be explained by partial volume effects due to limited spatial resolution in 4D flow MRI. The latter can further introduce a bias in estimation of derived parameters such as wall shear stress and reduce the ability to accurately segment the vessel lumen (5). An increase in spatial resolution, however, requires longer acquisition times, which are already challenging for clinical applications when using current resolutions. In addition, enhancing the resolution decreases the SNR, which results in an inversely proportional increase in velocity noise (44).

In this work, we applied 4D flow MRI at 7T in order to address the SNR reduction caused by increasing the spatial resolution and we addressed the acquisition time by applying kt-GRAPPA. However, a substantial challenge at 7T, particularly in body applications, is the spatial heterogeneity of transmit and receive B1 profiles, which leads to spatially variable flip angles, signal amplitudes and SNR. The goal was to address these B1+ variations and to investigate the impact on flow quantification. Therefore, we applied dynamic B1+ shimming, an approach successfully applied in previous studies conducted in our center (28) and by others (25).

When targeting the aorta, applying an efficient B1+ shim solution may be a reasonable approach, because homogeneous solutions optimized for larger ROIs typically require high power levels (35). Furthermore, 4D flow imaging relies on the phase of the MR signal, which is typically not sensitive to B1+ magnitude variations. However, we found that choosing an efficient B1+ shim solution created a pronounced local loss in B1+ magnitude in the distal arch in 5 out of 8 subjects, which locally biased the quantified signal. This effect was particularly apparent in 3D visualizations of the underlying velocity data revealing discontinuous particle traces at the location of low B1+. Interestingly, lower net flow rates were also observed in the AAo with the efficient B1+ shim, although |B1+| was higher in all subjects compared to the homogeneous solution. These results suggest that a combination of several effects may be responsible for the lower net flow values obtained with the efficient B1+ shim solution. For example, the efficient B1+ shim solution yielded strong variations in signal magnitudes in AAo and the Arch over the cardiac cycle, likely caused by saturation effects. Furthermore, with the efficient B1+ shim an increased intensity of replication artifacts (often present in thoracic or abdominal scans despite respiration triggering) was observed in the first few phases of the cardiac cycle fading out towards later phases. This effect may affect the flow quantification because artifacts from static tissue are aliasing into the aorta.

The homogeneous algorithm tends to achieve a more uniform excitation by reducing B1+ efficiency in regions close to the coil elements while increasing B1+ efficiency as in the arch. Therefore, it is important to note, that the flip angle for a given RF voltage is ultimately dictated by the efficiency in the arch where the maximum available B1+ is the lowest because of its distance to the coil elements. In this study, local efficiency values in the arch as high as 50% could be obtained to achieve homogeneous excitation. The solution produced remarkably constant signal magnitude over the cardiac cycle without the replication artifacts seen in the efficient shim solution.

Replication artifacts may also be caused by imperfect cardiac triggering, particularly at 7T where the strong magneto-hydrodynamic effect impacts the ECG. Despite careful positioning of the electrodes, we observed false trigger events in all subjects. In practice, if multiple successive false events were detected, the scan was aborted and restarted using a different ECG detection algorithm available at the scanner. Despite this procedure, we observed in subject 4 for protocol C stronger replication artifacts in anterior-posterior direction, which affected in particular the root and dDAo. This effect may explain the different flow values measured in dDAo and root in this subject, while flow values within AAo, Arch and pDAo, which were less affected by these artifacts, showed less deviation from results obtained with protocols A and B. Variations were also seen in subject 8, where a trend towards lower flow values was observed from protocol A to protocol C. The trend in this subject, who had a low but varying heart rate (45–70 beats per minute), might be explained by physiological changes, as protocol C started 30 minutes after protocol A.

When targeting the diaphragm, the efficient B1+ shim solution applied to the navigator, enabled a clear delineation of the diaphragm-lung boundary. This delineation was not visible with neither the initial B1+ shim setting nor with the homogeneous B1+ shim setting optimized for the aorta. A static B1+ shim solution was also investigated in subject 1, which was a trade-off between homogeneous B1+ in the aorta and high B1+ in the diaphragm. Although this static B1+ shim approach provided similar results as obtained with dynamic B1+ shimming, a reduced navigator acceptance rate was obtained, which is likely due to a less defined diaphragm-lung boundary. Therefore, to avoid an increase in measurement time dynamic B1+ shimming was the preferred solution.

While non-uniform transmit B1 was addressed using B1+ shimming in this study, the heterogeneity of the receive B1 field also posed a challenge. Analysis of the velocity in the aorta included segmentation of the aorta during post-processing. At lower field strength with less spatial receive profile variation, segmentation can be performed semi-automatically using a noise thresholding step and/or region growing algorithms based on phase contrast MR angiograms generated from the 4D flow data. Due to the strongly varying magnitude, a semi-automatic approach was not feasible in this study. Attempts to correct the magnitude profile variation before PC Angiogram (PCA) generation and segmentation were not satisfactory because of significantly elevated noise levels in the Arch and pDAo causing the semi-automatic segmentation to fail. Therefore, a more sophisticated B1− correction is required for a streamlined post-processing. In this study, this problem was avoided by performing a fully manual segmentation based on the PCA in all subjects. A particular problem was experienced when the efficient B1+ shim (protocol B) was utilized because the PCA was additionally biased by strong B1+ variations. Therefore, the masks derived from protocol A were also applied to the data obtained with protocol B.

In this work the image acquisition time was reduced by applying kt-GRAPPA. The technique utilizes measured data from adjacent cardiac phases for the image reconstruction of a given cardiac phase and it is known that velocities might be underestimated. We did not observe this effect with R=5, which is in agreement with a previous study performed at 3T (39). However, it should be noted that a higher spatial resolution in phase encoding direction for the kt-GRAPPA acquisition (2.4mm vs. 1.8mm) may counteract temporal blurring. Enabled by kt-GRAPPA, a further push to higher resolution (1.2mm isotropic) was shown to be feasible with encouraging results. Not only does the higher spatial resolution allow smaller sized structures to be visualized hinting that blood velocity could potentially be measured in significantly smaller vessels in the body, it is also expected to reduce partial volume effects. It should be noted, however, that the increase in resolution competes with reduction in SNR. In general, the tradeoff between low partial volume effects and high SNR will depend on the chosen venc and on the target region because the SNR strongly varies with distance to the RF coil at 7T.

Several limitations apply to this work. Due to the small number of subjects and the selection of healthy subjects, further investigations and the inclusion of patients with disorders are needed. The latter group may not tolerate the scans due to the long setup and scan time. Although the application of kt-GRAPPA with R=5 allowed acquiring the 4D flow protocol in less than 11 minutes, other approaches may need to be explored (and potentially combined) to further accelerate data acquisition for clinical application. Such approaches could include increasing the number of coil elements to achieve higher acceleration factors (15,45), applying radial acquisitions with high undersampling factors as in PC-VIPR (16), or using compressed sensing methods (20–22). Besides the acquisition time for the 4D flow protocol also the total session time is a limiting factor: in this work a period of 2.5–3 hours was required, including the setup, tuning/matching the RF coil elements, B1+ mapping, performing calibration routines, calculating B1+ shim solutions, and acquiring the 4D flow data. Several complementary approaches, actively investigated in several research center, should in the future allow for a substantial reduction of the total scan time, including utilizing novel RF coils that do not require tuning and matching, streamlining B1+ calibration and B1+ optimization, or selecting pre-calculated B1+ shim solutions according to the patient’s body shape out of a pool of solutions optimized for different body shapes.

Another limitation of this study is that not all scans were performed in all subjects, which was due to practical reasons. Due to the extensive setup and calibration procedure, we were only able to acquire protocols A and C in the first two subjects within a time period of 3 hours. During the course of the study the workflow improved allowing for adding protocol B starting with subject 3. Only towards the end of the study we were also able to acquire protocol D, which was then also repeated in a shorter session in the first subject.

Other limitations in this study are the long computational times for the kt-GRAPPA reconstruction (39) and the large raw data size of about 10 GB for the 1.2mm resolution acquisition. The 7 T system used in this study is equipped with a prototype image reconstruction system with 16 cores (2x Intel Xeon E5-2687w) and 128 GB of memory, which is dedicated to handle large amount of data. Although this system enabled the reconstruction of the high-resolution scan, the reconstruction still required approximately 15 minutes for the 1.8x1.8x2.4mm scan and about 90 minutes for the high resolution dataset. These reconstruction times would limit clinical applications, however, GPU based image reconstructions, which have not been applied in this study, may substantially reduce these computational times. It is also anticipated, considering the ever-growing speed and memory size of computers that in the long term standard MR systems will include sufficient computational resources.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates successful 4D flow imaging and spatiotemporal flow quantification within the thoracic aorta at 7 Tesla using kt-GRAPPA acceleration with acceleration factors of R=5 and dynamic B1+ shimming. Despite 4D flow MR imaging being a phase based method, reductions in signal magnitude caused by local B1+ defects can significantly alter flow quantification and impact streamline visualization, thus optimization of the transmit field appears to be required for 7T flow studies targeting the body. B1+ variations also impact the ability to accurately segment the aorta, therefore manual segmentation or more sophisticated automatic segmentation processes may be needed at 7 Tesla to accurately define the vessel lumen. No differences in net flow quantification were detected using kt-GRAPPA with R=5 in comparison to standard GRAPPA with R=2 and scan times of less than 11 minutes were achieved for above-standard resolutions, approaching the range of acceptable timeframe for clinical routine. The 5-fold acceleration in combination with the high SNR provided by 7 Tesla makes it possible to achieve even higher spatial resolution within reasonable scan duration, opening the prospect of targeting smaller vessels such as the coronary arteries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Malgorzata Marjanska and Steen Moeller for their comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grants (P41 EB015894, S10 RR026783) and by the W.M. KECK Foundation.

Footnotes

Parts of this study have been presented at the Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB 2014 in Milan, Italy.

References

- 1.Markl M, Frydrychowicz A, Kozerke S, Hope M, Wieben O. 4D flow MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;36(5):1015–1036. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wigstrom L, Sjoqvist L, Wranne B. Temporally resolved 3D phase-contrast imaging. Magn Reson Med. 1996;36(5):800–803. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910360521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogren HG, Mohiaddin RH, Kilner PJ, Jimenez-Borreguero LJ, Yang GZ, Firmin DN. Blood flow patterns in the thoracic aorta studied with three-directional MR velocity mapping: the effects of age and coronary artery disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7(5):784–793. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880070504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kozerke S, Hasenkam JM, Pedersen EM, Boesiger P. Visualization of flow patterns distal to aortic valve prostheses in humans using a fast approach for cine 3D velocity mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;13(5):690–698. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hope TA, Markl M, Wigstrom L, Alley MT, Miller DC, Herfkens RJ. Comparison of flow patterns in ascending aortic aneurysms and volunteers using four-dimensional magnetic resonance velocity mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2007;26(6):1471–1479. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissell MM, Hess AT, Biasiolli L, Glaze SJ, Loudon M, Pitcher A, Davis A, Prendergast B, Markl M, Barker AJ, Neubauer S, Myerson SG. Aortic dilation in bicuspid aortic valve disease: flow pattern is a major contributor and differs with valve fusion type. Circulation Cardiovascular imaging. 2013;6(4):499–507. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahadevia R, Barker AJ, Schnell S, Entezari P, Kansal P, Fedak PW, Malaisrie SC, McCarthy P, Collins J, Carr J, Markl M. Bicuspid aortic cusp fusion morphology alters aortic three-dimensional outflow patterns, wall shear stress, and expression of aortopathy. Circulation. 2014;129(6):673–682. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hope MD, Hope TA, Crook SE, Ordovas KG, Urbania TH, Alley MT, Higgins CB. 4D flow CMR in assessment of valve-related ascending aortic disease. JACC Cardiovascular imaging. 2011;4(7):781–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hope MD, Hope TA, Meadows AK, Ordovas KG, Urbania TH, Alley MT, Higgins CB. Bicuspid aortic valve: four-dimensional MR evaluation of ascending aortic systolic flow patterns. Radiology. 2010;255(1):53–61. doi: 10.1148/radiol.09091437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meierhofer C, Schneider EP, Lyko C, Hutter A, Martinoff S, Markl M, Hager A, Hess J, Stern H, Fratz S. Wall shear stress and flow patterns in the ascending aorta in patients with bicuspid aortic valves differ significantly from tricuspid aortic valves: a prospective study. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging. 2013;14(8):797–804. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dyverfeldt P, Kvitting JP, Sigfridsson A, Engvall J, Bolger AF, Ebbers T. Assessment of fluctuating velocities in disturbed cardiovascular blood flow: in vivo feasibility of generalized phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(3):655–663. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kvitting JP, Ebbers T, Wigstrom L, Engvall J, Olin CL, Bolger AF. Flow patterns in the aortic root and the aorta studied with time-resolved, 3-dimensional, phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging: implications for aortic valve-sparing surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127(6):1602–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bogren HG, Mohiaddin RH, Yang GZ, Kilner PJ, Firmin DN. Magnetic resonance velocity vector mapping of blood flow in thoracic aortic aneurysms and grafts. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;110(3):704–714. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5223(95)70102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stankovic Z, Allen BD, Garcia J, Jarvis KB, Markl M. 4D flow imaging with MRI. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2014;4(2):173–192. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2014.01.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stalder AF, Dong Z, Yang Q, Bock J, Hennig J, Markl M, Li K. Four-dimensional flow-sensitive MRI of the thoracic aorta: 12- versus 32-channel coil arrays. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2012;35(1):190–195. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson KM, Lum DP, Turski PA, Block WF, Mistretta CA, Wieben O. Improved 3D phase contrast MRI with off-resonance corrected dual echo VIPR. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(6):1329–1336. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung B, Honal M, Ullmann P, Hennig J, Markl M. Highly k-t-space-accelerated phase-contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2008;60(5):1169–1177. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baltes C, Kozerke S, Hansen MS, Pruessmann KP, Tsao J, Boesiger P. Accelerating cine phase-contrast flow measurements using k-t BLAST and k-t SENSE. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(6):1430–1438. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang F, Akao J, Vijayakumar S, Duensing GR, Limkeman M. k-t GRAPPA: a k-space implementation for dynamic MRI with high reduction factor. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(5):1172–1184. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lustig M, Donoho D, Pauly JM. Sparse MRI: The application of compressed sensing for rapid MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58(6):1182–1195. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D, Dyvorne HA, Otazo R, Feng L, Sodickson DK, Lee VS. Accelerated phase-contrast cine MRI using k-t SPARSE-SENSE. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(4):1054–1064. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsiao A, Tariq U, Alley MT, Lustig M, Vasanawala SS. Inlet and outlet valve flow and regurgitant volume may be directly and reliably quantified with accelerated, volumetric phase-contrast MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;41(2):376–385. doi: 10.1002/jmri.24578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lotz J, Doker R, Noeske R, Schuttert M, Felix R, Galanski M, Gutberlet M, Meyer GP. In vitro validation of phase-contrast flow measurements at 3 T in comparison to 1. 5 T: precision, accuracy, and signal-to-noise ratios. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2005;21(5):604–610. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bammer R, Hope TA, Aksoy M, Alley MT. Time-resolved 3D quantitative flow MRI of the major intracranial vessels: initial experience and comparative evaluation at 1.5T and 3. 0T in combination with parallel imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2007;57(1):127–140. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hess AT, Bissell MM, Ntusi NA, Lewis AJ, Tunnicliffe EM, Greiser A, Stalder AF, Francis JM, Myerson SG, Neubauer S, Robson MD. Aortic 4D flow: Quantification of signal-to-noise ratio as a function of field strength and contrast enhancement for 1.5T, 3T, and 7T. Magn Reson Med. 2014 doi: 10.1002/mrm.25317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Ooij P, Zwanenburg JJ, Visser F, Majoie CB, vanBavel E, Hendrikse J, Nederveen AJ. Quantification and visualization of flow in the Circle of Willis: time-resolved three-dimensional phase contrast MRI at 7 T compared with 3 T. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(3):868–876. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Berg P, Stucht D, Janiga G, Beuing O, Speck O, Thevenin D. Cerebral blood flow in a healthy Circle of Willis and two intracranial aneurysms: computational fluid dynamics versus four-dimensional phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of biomechanical engineering. 2014;136(4) doi: 10.1115/1.4026108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metzger GJ, Auerbach EJ, Akgun C, Simonson J, Bi X, Ugurbil K, van de Moortele PF. Dynamically applied B1+ shimming solutions for non-contrast enhanced renal angiography at 7. 0 Tesla. Magn Reson Med. 2013;69(1):114–126. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orzada S, Maderwald S, Poser BA, Bitz AK, Quick HH, Ladd ME. RF excitation using time interleaved acquisition of modes (TIAMO) to address B1 inhomogeneity in high-field MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(2):327–333. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitter S, DelaBarre L, Wu X, Greiser A, Wang D, Auerbach EJ, Vaughan JT, Ugurbil K, Van de Moortele PF. Cardiac imaging at 7 Tesla: Single- and two-spoke radiofrequency pulse design with 16-channel parallel excitation. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(5):1210–1219. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vaughan JT, Snyder CJ, DelaBarre LJ, Bolan PJ, Tian J, Bolinger L, Adriany G, Andersen P, Strupp J, Ugurbil K. Whole-body imaging at 7T: preliminary results. Magn Reson Med. 2009;61(1):244–248. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schmitter S, Wu X, Auerbach EJ, Adriany G, Pfeuffer J, Hamm M, Ugurbil K, van de Moortele PF. Seven-tesla time-of-flight angiography using a 16-channel parallel transmit system with power-constrained 3-dimensional spoke radiofrequency pulse design. Invest Radiol. 2014;49(5):314–325. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snyder CJ, Delabarre L, Moeller S, Tian J, Akgun C, Van de Moortele PF, Bolan PJ, Ugurbil K, Vaughan JT, Metzger GJ. Comparison between eight- and sixteen-channel TEM transceive arrays for body imaging at 7 T. Magn Reson Med. 2012;67(4):954–964. doi: 10.1002/mrm.23070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van de Moortele PF, Ugurbil K. Very Fast Multi Channel B1 Calibration at High Field in the Small Flip Angle Regime. Proceedings of the 17th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Honolulu, USA. 2009. p. Abstract 367. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitter S, Wu X, Adriany G, Auerbach EJ, Ugurbil K, Moortele PF. Cerebral TOF angiography at 7T: Impact of B1 (+) shimming with a 16-channel transceiver array. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(3):966–977. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van de Moortele PF, Akgun C, Adriany G, Moeller S, Ritter J, Collins CM, Smith MB, Vaughan JT, Ugurbil K. B(1) destructive interferences and spatial phase patterns at 7 T with a head transceiver array coil. Magn Reson Med. 2005;54(6):1503–1518. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Griswold MA, Jakob PM, Heidemann RM, Nittka M, Jellus V, Wang J, Kiefer B, Haase A. Generalized autocalibrating partially parallel acquisitions (GRAPPA) Magn {R}eson {M}ed. 2002;47(6):1202–1210. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jung B, Ullmann P, Honal M, Bauer S, Hennig J, Markl M. Parallel MRI with extended and averaged GRAPPA kernels (PEAK-GRAPPA): optimized spatiotemporal dynamic imaging. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;28(5):1226–1232. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schnell S, Markl M, Entezari P, Mahadewia RJ, Semaan E, Stankovic Z, Collins J, Carr J, Jung B. k-t GRAPPA accelerated four-dimensional flow MRI in the aorta: effect on scan time, image quality, and quantification of flow and wall shear stress. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(2):522–533. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bock J, Kreher BW, Hennig J, Markl M. Optimized pre-processing of time-resolved 2D and 3D Phase Contrast MRI data. Proceedings of the 15th Annual Meeting of ISMRM; Berlin, Germany. 2007. p. Abstract 3138. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Walker PG, Cranney GB, Scheidegger MB, Waseleski G, Pohost GM, Yoganathan AP. Semiautomated method for noise reduction and background phase error correction in MR phase velocity data. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1993;3(3):521–530. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1880030315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harloff A, Zech T, Wegent F, Strecker C, Weiller C, Markl M. Comparison of blood flow velocity quantification by 4D flow MR imaging with ultrasound at the carotid bifurcation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2013;34(7):1407–1413. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burk J, Blanke P, Stankovic Z, Barker A, Russe M, Geiger J, Frydrychowicz A, Langer M, Markl M. Evaluation of 3D blood flow patterns and wall shear stress in the normal and dilated thoracic aorta using flow-sensitive 4D CMR. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:84. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-14-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pelc NJ, Herfkens RJ, Shimakawa A, Enzmann DR. Phase contrast cine magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Q. 1991;7(4):229–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Graessl A, Renz W, Hezel F, Dieringer MA, Winter L, Oezerdem C, Rieger J, Kellman P, Santoro D, Lindel TD, Frauenrath T, Pfeiffer H, Niendorf T. Modular 32-channel transceiver coil array for cardiac MRI at 7. 0T. Magn Reson Med. 2014;72(1):276–290. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.