Abstract

Electronic cigarettes (ECIGs) use electricity to power a heating element that aerosolizes a liquid that often contains solvents, flavorants, and the dependence-producing drug nicotine for user inhalation. ECIGs have evolved rapidly in the past 8 years, and the changes in product design and liquid constituents affect the resulting toxicant yield in the aerosol and delivery to the user. This rapid evolution has been accompanied by dramatic increases in ECIG use prevalence in many countries, including among adults and especially adolescents in the United States. This increased prevalence of a novel product that has the potential to deliver nicotine and other toxicants to users’ lungs drives a rapidly growing research effort. This review highlights the most recent information regarding the design of ECIGs and liquid and aerosol constituents, the epidemiology of ECIG use among adolescents and adults (including correlates of ECIG use), and preclinical and clinical research regarding ECIG effects. The current literature suggests a strong rationale for an empirical regulatory approach toward ECIGs that balances any potential ECIG-mediated decreases in health risks for smokers who use them as substitutes for tobacco cigarettes and against any increased risks for nonsmokers who may be attracted to them.

Keywords: electronic cigarette, tobacco control, review

Introduction

Tobacco use remains the leading cause of preventable death in the United States.1 Currently, 18% of U.S. adults are cigarette smokers.2 While many smokers want to quit, few are able to do so successfully (e.g., Ref. 3), primarily because they are dependent on tobacco-delivered nicotine. These nicotine-dependent smokers inhale many disease-causing toxicants daily,1 and this toxicant inhalation leads to disability, disease, and over 400,000 U.S. deaths (possibly more than 500,000) each year.1,4 Thus, reducing cigarette smoking is a major public health goal.1 Traditional methods for reducing smoking involve prevention campaigns, restrictions on cigarette marketing and access, increased taxes, and improved cessation strategies.1 In the United States, these methods have reduced cigarette smoking from a high of 42% in 19655,6 to current levels of 18% among adults2 and 13% among adolescents in grades 9–12.7 However, given smoking’s prevalence, public health cost, and popularity among adolescents and young adults, some have argued that nontraditional approaches are needed.8,9,10 One of the most controversial of these approaches involves the use of a new class of products—electronic cigarettes (ECIGs)—as a means by which tobacco cigarette smokers might reduce or perhaps eliminate their combustible tobacco use.11,12 There have been some suggestions that these products could end tobacco smoking worldwide (e.g., Ref. 13).

Today’s ECIG was patented in 2003,14 and the product is intended to aerosolize a nicotine-containing liquid for inhalation. To the extent that the nicotine in the liquid is plant derived and the product is not marketed with therapeutic intent, ECIGs are considered tobacco products under U.S. law.15 This legal determination, coupled with the fact that ECIGs currently are not under the authority of the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Center for Tobacco Products, means that they have been marketed in an almost regulation-free environment that has seen them spread and evolve with very little understanding of what they are and what they do. Unanswered questions include “What are ECIGs and how do design features influence emissions?” “Will otherwise nicotine-free non-smokers, particularly adolescents, begin using ECIGs?“ “What are the short- and long-term health effects of ECIG use?” and “Can ECIGs help smokers quit tobacco cigarettes?” The critical nature of these questions has driven a growing research effort, and several recently published reviews (e.g., Refs. 16–18) document early results from studies that tended to focus on individual products in laboratory experiments (e.g., Refs. 19–21) or a conglomeration of undifferentiated products in epidemiologic work (e.g., Refs. 22–24). The goal of this review is to summarize the most recent published literature regarding ECIGs (2012–2015) and to begin to elaborate a systematic approach to learning more about this product class. To accomplish this goal, on June 9, 2015 we searched PubMed for relevant scientific documents that were not review articles with the following search strategy: (“electronic cigarette” or “electronic cigarettes” or “e-cigarette” or “e-cigarettes” or “electronic nicotine delivery”) AND (“2012/01/01”[Date – Publication] : “3000”[Date – Publication]) NOT “review”[Publication Type]. We obtained 818 hits, which we inspected in order to identify those that were English language and reported original data (i.e., were not editorials, news items, etc.), leaving us with 381 articles. The review will discuss the most relevant of these articles, first with regard to the design of ECIGs, the ingredients in their liquids, and the constituents of the aerosols they produce. It will then focus on the most recent information on epidemiology among adolescents and adults, results of studies examining ECIG aerosol effects on body systems, and the effects of ECIG use on tobacco cigarette smoking and related outcomes.

ECIGs and their design features

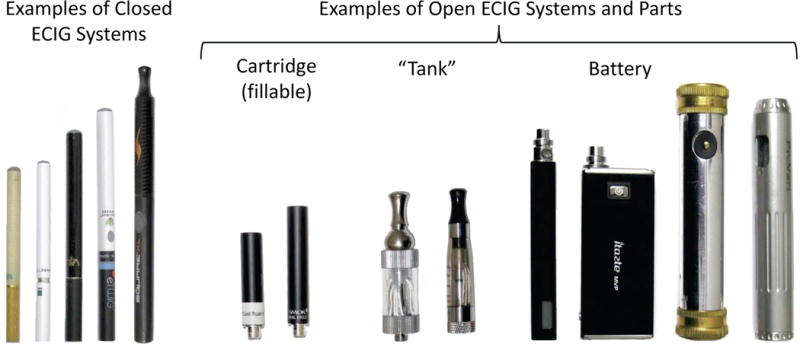

Most ECIGs consist of a battery, an electrical heater, and a liquid that is aerosolized for users to inhale. The name “electronic cigarette” actually encompasses a variety of design types, from products that look like a cigarette (sometimes called “first-generation devices” or “cigalikes”) to products that can be much larger than a cigarette and may use a cartridge or tank to hold the liquid, and that generally have a battery that is separate from the cartridge or tank (Fig. 1). Because most cigalikes are “closed” in that they are not intended to be refilled with liquid nor their battery or atomizer replaced by the user, and many cartridge- or tank-based systems are “open” in that they are intended to be refilled and often allow users to select and replace some components, we refer to these products as closed and open ECIGs. ECIGs also have a variety of names, such as “vapes,” “mods,” “e-hookahs,” and “vape pens.”

Figure 1.

Examples of open and closed electronic cigarette systems.

Aside from appearance, ECIGs can differ based on a variety of features, including but not limited to voltage and resistance (which together determine device power output). The liquids are usually (but not always) composed of nicotine, as well as at least one solvent (usually propylene glycol and/or vegetable glycerin), and flavorants (tobacco, menthol, candy or beverage themed, and more). As described below, these features combine with user puffing behavior to influence the toxicant content (or yield) of the aerosol that emerges from the ECIG.

The influence of voltage and resistance (power) on aerosol constituent yield

Different ECIGs have batteries with different voltages (the force that drives an electrical current through the ECIG heating coil), usually ranging from 3 to 6 V, and some ECIGs allow the user to adjust device voltage (Fig. 1). ECIGs also differ in the resistance (measured in Ohms) of the heating element, which is usually made from a nichrome wire (80% nickel, 20% chrome), but sometimes can be made from kanthal, an alloy mainly made of iron, chromium (20–30%), and aluminum (4–8%), or ceramic. The resistance in commonly marketed ECIGs falls in the range 1.0–6.5 Ω, though some can be found with resistance < 1.0 Ω. ECIGs can have one or more heating elements, and element number affects the net resistance. Together, voltage and resistance determine ECIG power output (P = V2/R, in Watts), which is one factor that affects the yield and toxicant content of ECIG aerosols.25 Commonly, ECIG power ranges between 4 and 11 W. Generally speaking, closed systems have lower-voltage batteries and/or higher-resistance heating elements because these systems are designed to look and feel like tobacco cigarettes and thus are constrained by size limitations (though exceptions to this general rule may exist). Finally, the presence of a wick may influence nicotine yield, though no published data address this point. Open systems, which are often larger than cigarettes, have fewer size constraints and therefore often have larger batteries that can provide power longer to a heating element with less resistance.

In general, nicotine yield (the amount of nicotine, measured in mg, that emerges from the mouth end of an ECIG after some number of puffs) is measured by trapping the machine-generated aerosol on filter pads and then extracting these pads with a suitable solvent or mixture of solvents. The impact of power output on ECIG aerosol nicotine yield has been examined in very few studies. For example, one study examined a variety of factors that can influence nicotine yield, and found that increasing power output from 3 to 7.5 W (an approximately 2.5-fold increase), by increasing the voltage from 3.3 to 5.2 V, led to an approximately 4- to 5-fold increase in nicotine yield.25 Device power includes heater resistance as well as voltage of the power source, and lowering the resistance of the heater also likely increases nicotine yield (all other things being equal). Clearly more work is needed to understand the effect of the range of ECIG power output possibilities on the nicotine yield of the resulting aerosol.

In addition to nicotine, ECIG aerosol can contain other toxicants, some of which are created by the thermal breakdown of liquid ingredients.26–29 These harmful constituents include glycols, aldehydes, metals, volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs30). Glyoxal and methyl glyoxal (aldehydes) have also been found in the ECIG aerosol; these compounds do not appear in cigarette smoke.31 This thermal breakdown is affected by device differences that may include electrical power. For example, in one systematic study, voltage was increased from 3.2 to 4.8 V and subsequent analysis of the aerosol revealed a 4- to 200-fold increase in formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, and acetone yield32 (see also Ref. 33). Indeed, ECIG aerosol formaldehyde yield in this study was in the range of that observed in tobacco smoke.32 Some of these results33 may reflect use parameters that differ from those reported by some experienced ECIG users,34,35,36 though there is substantial variability in these parameters.36 Other factors, including the way the device is used and the liquid constituents, can also influence ECIG volatile aldehyde yield.37–40 For example, devices that allow dripping liquid directly onto the heating element, a practice common among some users, results in aldehyde generation equal or higher than tobacco cigarettes, due to the higher temperature reached by the element.41 Also, reactive oxygen species (ROS; mainly radicals and peroxides) can be found in ECIG aerosol; one study revealed that ROS were detected from an activated element even without liquid and that new elements produced more ROS than used ones.42 VOCs (associated with irritation, headaches, and organ damage, among other effects) and PAHs (carcinogens) have also been assessed in ECIG emissions. Some studies report that levels are concerning (e.g., Ref. 43), while others report that the levels are lower than for cigarettes,39 or are so low that they do not present a significant risk.39–44 Finally, the presence of metals and silicate particles (associated with respiratory irritation and impaired lung function) in ECIG aerosol has been reported by several groups,45, 46 although some have reported only trace amounts.

The influence of liquid ingredients on aerosol constituent yield

The nicotine, propylene glycol (PG) and/or vegetable glycerin (VG), and flavorants in ECIG liquid can also influence the constituent yield of an ECIG aerosol. For example, commonly available ECIG liquid nicotine concentrations range from 0 to 36 mg/mL, with at least one closed system exceeding 50 mg/mL (https://www.juulvapor.com/support/faq/). A variety of studies have examined the aerosol nicotine yield of ECIGs that differed by the concentration of nicotine in their liquid.25,28,38,47 In one, the nicotine concentration in the liquid directly influenced the nicotine yield in the resulting aerosol.25 Specifically, this study examined an 8.26-mg/mL liquid and a 15.73-mg/mL liquid, and when other variables were held constant (puff duration of 4 seconds, puff volume of 68 mL, 3.3-V battery, 3.6-Ω heater), nicotine yield increased from 0.30 (SD = 0.01) to 0.48 (SD = 0.13) mg, indicating a 1.6-fold increase. Other studies have also reported a positive relationship between the nicotine liquid concentration and the nicotine yield,28, 47 though not always.48 In addition, liquid pH must be considered,49,50 as pH can affect the aerosol yield and distribution of free-base and protonated nicotine.51 Also, a recent study reported that some liquids may contain more nicotyrine than others;52 nicotyrine can inhibit in vivo metabolism of nicotine, which may increase nicotine delivery in ECIG users.53 Finally, because the nicotine in ECIGs is derived from the tobacco plant, the liquid can contain other tobacco-related toxicants, such as tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) that are known carcinogens.54 In studies of select ECIGs, TSNAs have been found in the liquid and the aerosol produced when the heater is activated, but at much lower levels than in tobacco cigarettes.39,55,56

The ratio of propylene glycol (PG) to vegetable glycerin (VG) in ECIG liquid can be 0:100, 100:0 or anywhere in between. Solvent content is important due to differences in the physical properties of the solvents. For example, the generation of the aerosol can be affected by the boiling point of the solvent, which differs for PG (188 °C) and VG (290 °C). The higher boiling point of VG allows the element to reach a higher temperature, and this may influence ECIG toxicant emissions.41 Aside from boiling point, the solvent used can affect the particle-size distribution of an ECIG aerosol.57 Particle size affects the region of deposition in the respiratory system: smaller particles deliver more nicotine to the alveoli.58 To date, several studies have examined particle size and concentration in ECIG aerosols (e.g., Refs. 43 and 59–63) In general, VG yields larger particles than PG, and the presence of nicotine or flavors has no effect on the particle-size distribution.63 However, this literature has not taken a systematic approach to studying all of the different factors that may influence particle size, and has also used different methods of particle counting.64 Finally, the ratio of PG to VG may also influence ROS; one study showed that a PG/VG mixture produced more ROS than each one alone.42 In another study, the type of solvent affected the yield of aldehydes; liquid with PG as the solvent resulted in the highest yield of aldehydes.32

Flavorants in the liquid also contribute to aerosol constituent yield. While the flavorants are often identified by manufacturers as “generally recognized as safe” food additives, they may not have been tested for safety when inhaled. Several studies have investigated the effects of flavorants in ECIG liquids.27,65–71 However, because users inhale the aerosol, and not the liquid, systematic study of flavorant contribution to ECIG aerosol yields is required.72

The influence of user behavior on aerosol constituent yield

The puffing behavior of an individual using either a combustible cigarette or an ECIG can be assessed by measuring several key variables, including puff volume, flow rate (the volume of air traveling through the product per unit time), puff duration, and interpuff interval.73–75 These “puff topography” measures76 have been manipulated systematically in the laboratory to determine to what extent they influence ECIG nicotine yield.25 Results showed that flow rate does not influence nicotine yield, though longer duration puffs do, likely because the heating element is activated for a longer time.25 To date, this systematic approach to understanding ECIG toxicant yield has been applied to nicotine only, and there is an urgent need to use it in understanding factors that influence other toxicant emissions.

Summary

Overall, many factors affect the toxicant yield of ECIGs, including ECIG design, liquid contents, and user behavior. To understand the impact of each factor adequately, ECIGs must be studied systematically, and none of the factors discussed above (design, power output, liquid vehicle, nicotine concentration, flavorants, and puff topography) can be examined in isolation when discussing their influence on toxicant yield. In order to address the effects of variations in all the aforementioned factors on nicotine yield systematically, a mathematical model has been developed.25 In this model, each parameter can be changed individually, and the model can account for a wider range of variations than can be done with experimental work. In a preliminary evaluation examining the relationship between model-predicted and actual measured nicotine yield, a 99% fit was obtained.25 There is a growing need for similar models that predict the yield of other ECIG aerosol toxicants.

Epidemiology of ECIG use

With any emerging behavior, obtaining accurate prevalence estimates presents challenges due to delays between assessment and data dissemination. However, a growing literature documents ECIG use trends among adolescents and adults.

Prevalence among adolescents

ECIG use prevalence among adolescents (typically defined as individuals 10–19 years of age) has been studied primarily in local or regional rather than nationally-representative samples.77–86 The most commonly reported prevalence measures are ever use (any ECIG use in an individual’s lifetime) or current use (ECIG use in the 30 days before participating in a study). In the United States, nationally representative data indicate that ECIG use has increased rapidly in recent years. Data collected in 2011 indicated that 3.1–3.2% of middle school and high school students had ever been ECIG users87–89 and 0.6–1.5% were current users.7,88,90–91 In 2012, 6.5–6.8% of middle school and high school students had ever been ECIG users,88,90–91,93–94 and 2.0–2.8% were current users.7,88,90–92,93–95 In 2013, 3.0% of middle school students and 11.9% of high school students had ever been ECIG users,7 and 1.1% of middle school students and 4.5% of high school students were current ECIG users.7 In 2014, current ECIG use among middle school students (3.3%) and high school students (11.9%) tripled from the previous year7 (Fig. 3). The same trend is occurring worldwide, as shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Current (past 30 days) ECIG use trends among U.S. adults, high school students, and middle school students.7,90,136,139

Table 1.

Ever and current electronic cigarette use among youth and adult general populations around the world.

| Country | Population | Year | Ever used | Current use | Study | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescents | ||||||

| Canada | Adolescents and young adults (16–30 year olds) | 2012 | – | 5.7% | Czoli et al., 2014103 | |

| Finland | Adolescents | 2013 | 17.4% | – | Kinnunen et al., 2014101 | |

| Germany | Adolescents | 2012 | 4.7% | – | Hanewinkel et al., 2015100 | |

| Ireland | Adolescents | 2014 | – | 3.2% | Babineau et al., 2015104 | |

| New Zealand | Adolescents | 2012 | 7.0% | – | White et al., 201598 | |

| Adolescents | 2014 | 20.0% | – | White et al., 201598 | ||

| Poland | High school students | 2010–2011 | – | 8.2% | Goniewicz et al., 201296 | |

| High school students | 2013–2014 | – | 29.9% | Goniewicz et al., 201497 | ||

| South Korea | Adolescents | 2011 | 9.4% | – | Lee et al., 201499 | |

| 12th grade students | 2011 | – | 5.9% | Lee et al., 201499 | ||

| Wales | 11–16 year olds | 2013–2014 | 12.3% | 1.5% | Moore et al., 2015102 | |

| Adults | ||||||

| Indonesia | Adults | 2011 | – | 0.3% | Palipudi et al., 2015149 | |

| Italy | Adults | 2013 | 6.8% | 1.2% | Gallus et al., 2014147 | |

| Greece | Adults | 2013 | – | 1.9% | Palipudi et al., 2015149 | |

| Malaysia | Adults | 2015 | – | 0.8% | Palipudi et al., 2015149 | |

| New Zealand | Adults | 2014 | – | 0.8% | Li et al., 2015148 | |

| Poland | University students | 2010–2011 | 19.0% | 5.9% | Goniewicz et al., 201296 | |

| Qatar | Adults | 2013 | – | 0.9% | Palipudi et al., 2015149 | |

| Switzerland | Young adult men | 2010–2013 | 4.9% (past 12 month use) | – | Douptcheva et al., 2013146 | |

Adolescents report a variety of reasons for ECIG initiation and use, including curiosity, the availability of appealing flavors, being influenced by peers,98,105 and being able to conceal their use,106 among many others (Table S1). However, adolescents do not identify using ECIGs as a smoking cessation aid as a reason to initiate ECIG use.89 An important point to note regarding the correlates and risk factors of ECIG use among adolescents is that while one of the strongest and most commonly reported risk factors for ECIG use is cigarette or other tobacco use, there are adolescents who have never smoked cigarettes or never used any tobacco product at all who initiate ECIG use.77,80–82,91,94,96,98,107–110 For example, in 2012, an estimated 160,000 students who had never used combustible tobacco cigarettes reported ever having used an ECIG,91 and some data indicate there are more adolescent exclusive ECIG users than adolescent ECIG and cigarette dual users.109 Increasing rates of ECIG use among otherwise nicotine-naive adolescents represents a growing public health concern.

Prevalence among adults

ECIG use among adults has also become more prevalent in the United States within the past 5 years. While there are many studies that examine adult ECIG use among non-nationally representative samples,22–23,112–134 data from nationally representative samples of U.S. adults indicate that ECIG use prevalence rates are rising (Fig. 3; the prevalence estimates from each of these surveys were averaged for 2010–2013, giving equal weight to each study). In 2009–2010, 0.6–2.5% of adults reported having ever used ECIGs24,135–138 and 0.3% reported current ECIG use.136 In 2011, 6.2–7.3% of adults reported having ever used ECIGs24,136,139 and 0.8% reported current use.136 In 2012–2013, 6.0–14.0% reported having ever used ECIGs136,139–142 and 1.4–6.8% reported current ECIG use.136,140,142–143

Adults also use ECIGs in other countries. Prevalence data among the general adult population is shown in Table 1. Additionally, among current and former combustible cigarette smokers, ever having used ECIGs has been reported in Canada (4.0% in 2010–2011),22,23 the United Kingdom (9.6–26.9% in 2010–2012),22,23,150 France (22.6% in 2012),150 Belgium (11.5% in 2012),50 Austria (13.7% in 2012),150 Germany (20.2% in 2012),150 the Netherlands (18.0–21.9% in 2013),23,150 Luxemborg (28.0% in 2012), Greece (22.4% in 2012),150 Malta (16.7% in 2012),150 Portugal (17.0% in 2012),150 Slovenia (20.3% in 2012),150 Spain (10.9% in 2012),150 Cyprus (23.6% in 2012),150 Denmark (36.3% in 2012),150 Slovakia (7.9% in 2012),150 the Czech Republic (34.3% in 2012),150 Ireland (12.1% in 2012),150 Latvia (23.9% in 2012),150 Lithuania (11.8% in 2012),150 Finland (20.5% in 2012),150 Sweden (12.4% in 2012),150 Estonia (22.3% in 2012),150 Hungary (22.3% in 2012),150 Bulgaria (31.1% in 2012),150 Romania (22.2% in 2012), Australia (2.0–20.0% in 2010–2013),22–23 Italy (5.6% in 2013),150 Poland (31.0% in 2012),150 Malaysia (19% in 2011),23 Brazil (8% in 2013),23 Mexico (4% in 2011),23 South Korea (11% in 2010),23 Brazil (8% in 2013),23 and China (2% in 2009),23 and current ECIG use has been reported in Canada (1.0% in 2010–2011),22,23 the United Kingdom (4.0% in 2010–2011),22,23 Australia (1.0–7.0% in 2010–2013),22,23 the Netherlands (3% in 2013),23 and China (0.05% in 2009).23 Although there are regional differences, these data indicate that ECIGs are popular among adults in the United States and in many countries around the world.

Unlike adolescent ECIG users, a common reason for ECIG use among adults is to aid in smoking cessation or reduce the number of combustible tobacco cigarettes used22,113,119,124,127,151–154,156,157 (Table 1). Additionally, while ECIGs are more common among adult cigarette smokers and many ECIG users volunteer smoking cessation as a reason for ECIG use, there is a large number of one-time and current adult ECIG users that reported having never smoked cigarettes.24,96,122,123,128,132,135,136,139,150,157 For example, in 2013, an estimated 1.7 million adults who had never smoked cigarettes reported having ever used ECIGs.139 While this group is not the majority, ECIGs are not only being used by current smokers to quit smoking.

Summary

ECIG use prevalence is increasing rapidly among adolescents and adults in the United States and internationally. Monitoring changes is prevalence is challenging for a variety of reasons, including the name of the product itself: inquiring about “electronic cigarette” use may fail to capture users of “vapes,” “mods,” “e-hookahs,” “vape pens,” or other names for devices that are, in fact, ECIGs. Future population studies would benefit from data-collection instruments that can accurately identify the wide variety of ECIG users in terms of the different types of products they use and how they use them. With respect to patterns of use, defining current ECIG use as any ECIG use within the past 30 days may not be ideal, as it could include ECIG experimenters who do not transition to continued use. Prevalence measures may be more accurate if they define current ECIG use differently, such as ECIG use on more than 5 days.158 Studies that examine use behaviors in more detail may provide more useful data that can guide health professionals and policy makers.

Effects of ECIGs in humans: studies using animal and human models

This section discusses the biological impacts of ECIG aerosol and considers effects on the respiratory, cardiovascular, and immunologic systems as well as the effects of nicotine on the central nervous system. Because users inhale aerosolized liquid and not the liquid itself, this section will focus on studies that have observed the effects of ECIG aerosols; those that tested ECIG liquid (e.g., Refs. 159–161) are excluded.

Respiratory system

Methods for evaluating the effect of ECIG aerosols on the respiratory system are under development, and the studies reviewed within this section differed on many variables, including ECIG devices, liquids, and aerosol exposure bout. In preclinical studies involving exposure of cultured cells to ECIG aerosol, the method of aerosol exposure was often the air–liquid interface42,162,163 where the cultured cells in liquid media were exposed to ECIG aerosol in the air above for varying time lengths. Others164,165 took a different approach and pad-collected ECIG aerosol and diluted it in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or cell media. Also, because different ECIG devices were used, there are cross-study differences in methods of aerosol generation. In one study, the aerosol produced from various open and closed devices had no significant cytotoxic effects on human lung cells.164 In another,165 ECIG aerosol and cigarette smoke were reconstituted at different concentrations in culture medium, which was then applied to cultured mouse fibroblast cells for 24 hours of incubation. With cigarette smoke, cytotoxic effects (< 70% cell viability) were observed at concentrations higher than 12.5%, while with ECIG aerosol cytotoxic effects were observed at the 100% extract concentration, indicating less toxicity for the ECIG aerosols under these conditions.165

Multiple studies suggest that exposure of ECIG aerosols to cells increased oxidative stress and decreased epithelial cell viability42,163 (measurements taken 24 h after ECIG aerosol exposure) as compared to clean air controls. The addition of nicotine to the aerosolized ECIG liquid increased oxidative stress in some studies163 and decreased it in others.42 One study found no toxicological responses (e.g., cytotoxic, genotoxic, or inflammatory)164 and another observed little decrease in cell viability165 after ECIG aerosol exposure. Again, the variability across studies in device, liquid, and aerosol-generation methods makes generalization challenging, but all but one study found some toxic effects on mammalian cells.

Studies have also been conducted using whole-animal exposure. For example, eight albino Wistar female rats were exposed to ECIG aerosol (produced from an open ECIG loaded with 0.9% weight/volume nicotine liquid) in an enclosed chamber for 1 hour per day for 4 weeks while a control group received no treatment.166 Vocal folds were evaluated for epithelial distribution, inflammation, hyperplasia, and metaplasia. There was no difference between the groups in epithelial distribution or inflammation; two cases of hyperplasia and four cases of metaplasia were identified in the ECIG aerosol exposed group while the control group exhibited no hyperplasia but one case of metaplasia. Statistically, there was no difference between the larynxes of the control and experimental groups.166 However, in another study,42 when 8-week-old mice were exposed to ECIG aerosol for 5 h over 3 successive days, proinflammatory cytokines increased and glutathione levels decreased;42 glutathione is protective against ROS such as free radicals, peroxides, and heavy metals. In another study,167 neonatal mice were exposed to ECIG aerosol generated from an open ECIG (3.3 V) for the first 10 days of their lives. Mice in the control group were exposed to room air. For the mice in the experimental group, each exposure consisted of aerosolizing liquid (PG based, 1.8% nicotine) in a cartridge, which took approximately 20 minutes, into the home cage once on days 1 and 2 of life, and twice a day during days 3–9. Pups were kept with their mothers during aerosol exposure, therefore some of the exposure could have been routed through breast milk. Pups exposed to the ECIG aerosol weighed 13.3% less and had moderately impaired lung growth (diminished alveolar cell proliferation) compared to controls. Importantly, alveolarization is not complete until 36 days of life in mice, and it was measured at the 10th day of life in this study. Together, these studies demonstrate some harmful effects of acute ECIG aerosol exposure while highlighting the need for systematic work using well-characterized devices, liquids, and aerosol-generation methods.

Existing clinical work examining the effects of ECIG aerosol exposure on the human respiratory system also makes generalization difficult owing to various methodological differences. In one clinical study,168 human participants completed separate sessions (separated by at least 24 h) in which they inhaled ECIG aerosol from an open-system ECIG that either contained no liquid (negative control), a 0 mg/mL nicotine liquid, or an 18 mg/mL nicotine liquid for 5 minutes; a conventional cigarette served as a positive control. Expired nitric oxide (NO) levels were measured before and after each session (NO is important for vasodilation and blood flow; cigarette smokers have reduced NO levels169). Following the 0 mg/mL ECIG session, participants had significantly decreased expired NO levels of 3.2 parts per billion (ppb); following the 18 mg/mL nicotine session, NO significantly decreased by 2.2 ppb; and following a conventional cigarette, NO significantly decreased by 2.8 ppb. The negative control condition did not significantly alter expired NO levels.168 In another study,170 also following 5 min of ad lib ECIG use with or without a cartridge containing 11 mg/mL nicotine liquid, the fraction of exhaled NO was decreased significantly in the cartridge condition. One study171 compared lung function and exhaled NO following smoking tobacco cigarettes or use of an open-system ECIG. Lung function was not affected by use of ECIG or passive exposure for an hour. While these latter results171 appear contradictory to those of the former studies168,170 differences in device, liquid, and measurement times make cross-study comparisons challenging. A complete understanding of the effects of ECIG aerosol inhalation on the human respiratory system awaits systematic investigation.

Cardiovascular system

Few preclinical studies have been conducted examining the effects of ECIG aerosol on the cardiovascular system. In one,172 200 mg of ECIG aerosol was dissolved into 20 mL of cell culture media and its effects were tested on monolayer-cultured H9c2 cardiomyoblast cells and compared to those of diluted combustible cigarette smoke. Twenty different flavors were tested in nicotine concentrations varying from 6 mg/mL to 24 mg/ml, the ECIG device battery voltage ranged from 3.7 V to 4.5 V, and the PG/VG ratio varied across flavors. Cigarette smoke was produced by 2-s puffs of 35 mL every 60 s from three cigarettes. The ECIG aerosol and the cigarette smoke were also used in several dilutions (100%, 50%, 25%, 12%, and 6.5%), and the effects of the ECIG aerosol and the smoke on cells were then compared. The ECIG aerosols produced using a 4.5-V ECIG resulted in reduced cell viability compared to the effects of the aerosol produced using a 3.7-V ECIG. Cigarette smoke was cytotoxic at all dilutions, and some ECIG aerosols were cytotoxic at higher dilutions only. These findings suggest, as with the respiratory cell culture experiments, that ECIG aerosol is less toxic than cigarette smoke in these preparations, but there may be some variation in cell viability, based on the power output of the device in which the aerosol is generated.

Another study173 observed the effects of ECIG aerosol and cigarette smoke in two preclinical preparations, one in vivo and another in vitro. The ECIG aerosol was generated using a 16 mg/mL nicotine solution. The authors used zebrafish (Danio rerio) to study the development of the cardiac system and human embryonic stem cells to study cardiac differentiation. Both ECIG aerosol and cigarette smoke resulted in developmental defects, heart malformation, pericardial edema, and reduced heart function.173 In the in vitro model, both ECIG aerosol and cigarette smoke decreased the expression of cardiac transcription factors, which could lead to a delay in cellular differentiation. Tobacco cigarette smoke induced more negative effects and therefore was more toxic than ECIG aerosol.173 Taken together, these studies demonstrate that there are harmful effects of ECIG aerosol; however, on the basis of research done so far in the few preparations used, the effects seem less severe than the effects of cigarette smoke.

Like cigarette smoke, clinical studies demonstrate that ECIG use elevates heart rate and blood pressure, likely due to the effects of nicotine. The acute cardiovascular effects of ECIGs have been observed in a few clinical studies;174–176 however, the long-terms effects of ECIGs are still relatively unknown. In one study, closed ECIG use (16 mg/mL nicotine for 50 5-s puffs at 30-s intervals, plus one hour of ad lib use) resulted in elevated heart rate and systolic and diastolic blood pressure, but less so than following combustible cigarette use.174 Further analysis revealed a correlation between plasma nicotine concentration and heart rate increase; therefore, ECIGs that deliver more nicotine to the user are likely associated with greater heart rate increases. Another study examined the effects of ECIG use on left ventricular myocardial function.177 Heavy smokers, healthy subjects, and experienced ECIG users (all former smokers) were compared following the use of an open ECIG with a 3.5-V battery and 11 mg/mL nicotine liquid. An echocardiographic examination was performed on participants before and after smoking a cigarette or using an ECIG ad lib for 7 min. Following acute ECIG use, no adverse effects were observed in left ventricular myocardial function, while significant changes were observed following smoking one cigarette.177 Another study observed the effects of cigarette smoke (10–12 puffs) and ECIG aerosols (15 puffs from a 3.4-V battery, 24 mg/mL nicotine concentration) on arterial stiffness and found that, while acute cigarette smoke increased arterial stiffness in cigarette smokers, ECIG use did not.176 Another study looked at the acute and passive effects of cigarette smoke and ECIG aerosols (open system with 11mg/mL nicotine liquid; session was 30 min of ad lib use) in current cigarette smokers and observed no difference on a complete blood count, while cigarette smoke (two cigarettes in 30 min) increased white blood cell, lymphocyte, and granulocyte counts.175

Generally, preclinical studies on the cardiovascular system demonstrate that there may be some developmental and molecular effects from ECIG use,173 but ECIGs do not appear to have more acute effects on the cardiovascular system than cigarettes.175,176 However, additional studies that systematically examine each ECIG parameter and its effects on cardiovascular function are needed.

Immunologic system

Concern about the immunological effects of ECIG liquid have also been raised, and animal studies show that nicotine, as well as ECIG liquid aerosol, can have negative effects on the immune system. Nicotine has been shown to impair antibacterial defenses178,179 and alter macrophage activation.180–182 In a set of experiments using a mouse model, ECIG aerosol exposure resulted in airway inflammation, impaired immunological response to bacteria and viruses, and impaired bacterial phagocytosis.183 Exposure to ECIG aerosol (1.8% nicotine; 2-s, 35-mL puff taken every 10 s diluted into air at 1.05 L/min) also increased virus-caused morbidity and mortality.183 Lung cell culture assays of these mice exposed to ECIG aerosol demonstrated defective bacterial phagocytosis (note that rodents metabolize nicotine faster than humans181).183

In addition, a recent study using rat, mouse, and human lung epithelial cell lines showed that exposure to nicotine alone, as well as nicotine-containing and nicotine-free ECIG aerosol condensate, diluted in cell media (the device used to generate the aerosol was not identified) can have deleterious effects, including disruption of lung endothelial lung barrier function, proinflammatory effects, and decreased cell proliferation.184 In whole-animal experiments, 4-month-old female mice were nebulized with nicotine, ECIG aerosol, or a saline control. Results demonstrated increased lung inflammation and oxidative stress under experimental conditions. The authors reported that the nicotine, acrolein, propylene glycol, and glycerol in ECIG aerosol are associated with lung inflammation.184 Similar effects occur after combustible tobacco use. However, some studies show that, when comparing the acute impact of ECIG aerosols to combustible tobacco smoke on lung function, ECIGs produce a less pronounced effect.171

Central nervous system

Nicotine is a psychomotor stimulant that is self-administered by humans and rats and can lead to dependence (e.g., Ref. 185) Nicotine crosses the blood–brain barrier and binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in various brain regions. The main structures implicated in dependence compose the reward pathway, which consists of the ventral tegmental area in the midbrain, the nucleus accumbens, and the prefrontal cortex, among others. A comprehensive review of the neurobiology of nicotine dependence is available elsewhere (e.g., Ref. 186).

As discussed above, many features of ECIG devices and liquids influence nicotine yield, and thus likely also influence nicotine delivery to the user, as indexed by increases in plasma nicotine concentration after ECIG use. Indeed, a variety of studies demonstrate that some ECIGs deliver very little nicotine while others are capable of delivering at least as much nicotine as a combustible tobacco cigarette174,187–189 (Fig. 4). User experience also plays a role in ECIG nicotine delivery, with more experienced users obtaining higher plasma nicotine concentrations after a fixed number of puffs than less experienced users.190,191

Figure 4.

Mean (+ SEM) plasma nicotine concentration from different human laboratory studies and different products with blood sampled before and immediately after a 10-puff product use bout. Combustible cigarette data are from 32 tobacco cigarette smokers using their usual brand of combustible cigarette.19 ECIG A is a “cigalike” product called “Blu” loaded with two different concentrations of liquid nicotine (16 or 24 mg/mL, both containing 20% propylene glycol and 50% vegetable glycerin). Data are from 23 tobacco cigarette smokers with 7 days experience with the product.174 ECIG B is a “cigalike” product called “V2cigs” and ECIG C is a “tank” product called “EVIC” with an “EVOD” heating element; both were loaded with an 18 mg/mL liquid containing 34% propylene glycol and 66% vegetable glycerin. Data are from 23 experienced electronic cigarette users.188 ECIG D is a 3.3-V “Ego” battery fitted with a 1.5-Ω dual-coil cartomizer (“Smoktech”) and filled with ~1 mL of a 70% propylene glycol/30% vegetable glycerin liquid that varied by liquid nicotine concentration (0, 8, 18, or 36 mg/mL). Data are from 16 experienced electronic cigarette users.194 Taken together, the figure shows the wide variability of nicotine delivery in marketed electronic cigarettes, many of which underperform a combustible tobacco cigarette, but some of which can, in the hands of experienced users, exceed the nicotine delivery of a combustible tobacco cigarette, depending on the liquid nicotine concentration.

Greater nicotine delivery has implications for the development of nicotine dependence, as regular exposure to higher doses of a dependence-producing drug lead to greater dependence on that drug (e.g., Ref. 192), and higher nicotine intake (as measured by cigarettes per day) is a key component of nicotine dependence measures (e.g., Ref. 193) Importantly, recent research suggests that some 3.3-V ECIG devices paired with relatively low-resistance heating elements (i.e., 1.5 Ω) loaded with 36 mg/mL liquid nicotine can result in plasma nicotine concentrations after 10 puffs that appear greater than those that are usually obtained by combustible tobacco cigarette smokers under similar conditions.194

While ECIGs have been shown to deliver physiologically active doses of nicotine, at least under some conditions, whether or not ECIGs are produce nicotine dependence remains an open question. A variety of published studies provide indirect evidence that ECIGs users experience a variety of indicators of nicotine dependence, as described further below. One potentially useful method for discussing these studies is to select a set of criteria for dependence and determine to what extent the study results address each criterion. One set of criteria for dependence that could be used for research comes from the World Health Organization’s ICD-10.195

For example, one ICD-10 criterion involves a strong desire or sense of compulsion to use a substance, and one survey of ECIG users showed that some reported a strong urge to use ECIGs (25–35% of the sample).196 Other studies have shown that ECIG users use ECIGs because of a strong desire or craving to use tobacco,e.g., 196–197 or that ECIGs can reduce craving for tobacco,198 which indicates tobacco dependence, and that tobacco dependence may be maintained (rather than engendered) by ECIG use.

Addressing another ICD-10 criterion, a few studies have explored the impaired capacity to control ECIG use, such as trouble stopping or cutting down. In one study, 29% of the participants (daily ECIG users) indicated that stopping ECIG use would be very difficult or impossible. In that same study, 33% of the daily ECIG users indicated that they would likely succeed if they decided to stop using the product.197 In another study, 11% of the ECIG users surveyed said that they would “find it hard to keep from using in places where you are not supposed to.”196 Thus, at least some ECIG users predict difficulty stopping their ECIG use, indicating an impaired capacity to control the behavior.

The presence of withdrawal symptoms experienced during drug abstinence is also among the ICD-10 criteria. In tobacco users, abstinence symptoms are often characterized by anxiety, difficulty concentrating, depressed mood, decreased heart rate, increased appetite or weight gain, insomnia, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and restlessness, among other signs and symptoms.199 There is some evidence that ECIG users may experience some of these abstinence symptoms. For example, in one study of ECIG users, 26% said they are “more irritable when they cannot use an e-cig” and 26% said they are “more nervous when they cannot use an e-cig.”196

Tolerance, as evidenced by increasing use of the drug to achieve a desired effect, is another ICD-10 criterion. One study197 looked at tolerance in ECIG users, as indicated by a score from questions on the nicotine dependence syndrome scale about increased use (NDSS).200 Daily ECIG users had a score of −1.15 (on a scale from −4 to +4), lower than the score for a sample of smokers in a separate study.200 Another study looked indirectly at tolerance, by surveying experienced ECIG users about whether or not they switched to more advanced systems (e.g., from closed system to open systems with larger batteries). In that study, 77% of participants switched devices to get a “more satisfying hit.”201 Among these users, it is possible that the change to a more advanced device was due to tolerance.

Preoccupation with drug use is also an ICD-10 criterion, and preoccupation with ECIGs was examined in one study,197 indicated by a score from questions on the nicotine dependence syndrome scale about priority of ECIG use, such as visits with non-ECIG–using friends and/or avoiding restaurants and airplanes (NDSS).200 Daily ECIG users had a score of −0.73 (on a scale from −4 to +4); lower than the score for a sample of smokers in a separate study.200

No published study in the search strategy used here examined continued use of ECIGs despite harmful consequences, which would address the final ICD-10 criterion. As shown in Table S1, some EICG users report using ECIGs because they perceive them to be less harmful than cigarettes.22,115,127,128 In addition, a survey of ECIG users (of whom 81% were former smokers) reported only mild adverse events related to using the ECIG that later resolved, such as dry mouth or throat.202 Overall, some ECIG users appear to experience some aspects of dependence, although the extent to which ECIGs are produce dependence (as opposed to maintaining dependence in former smokers who switch to ECIGs) remains unclear.

Extant work suggests that ECIGs may be associated with lower dependence than combustible cigarettes (and also less abuse potential).203,204 However, much of this work likely included participants who were using devices that delivered very little nicotine. Future studies need to examine ECIG dependence in long-term ECIG users with particular attention paid to the characteristics of the device/liquid combinations used. Further, specific dependence instruments may be needed for specific nicotine-delivery products205 or for products with specific characteristics.196 Determining the extent to which ECIG use engenders dependence in the otherwise nicotine-naive user is even more challenging, though of increasing importance as more adolescents who are not already tobacco users begin experimenting with these products.108

Effects of nicotine on fetal and adolescent development

In addition to dependence maintenance and development in ECIG users, ECIG-delivered nicotine may have other CNS effects, including effects on fetal development in pregnant women who use them and on the brain development of adolescent ECIG users. Few studies have examined these issues with regard to ECIG-delivered nicotine, but a robust preclinical and clinical literature supports the notion that nicotine exposure in utero and during adolescence can have profound CNS effects. A detailed description of these effects is beyond the scope of this review, especially as it does not reflect ECIG-delivered nicotine, but it is summarized briefly below and interested readers can refer to several comprehensive reviews for more information (e.g., Refs. 206–208)

Nicotine crosses the placenta, and preclinical work demonstrates that in utero nicotine exposure is a likely explanation for behavioral disorders observed in children of mothers who smoked during pregnancy, including (but not limited to) hyperactivity, cognitive impairment, anxiety, and sensitivity to nicotine and other stimulant drugs.207 These effects are likely attributable to nicotine’s role as an acetylcholine agonist, and acetylcholine receptors are present at very early stages of fetal development,207 which may help to explain why nicotine’s effects on the developing fetus are not limited to the CNS but can also include negative and long-lasting effects such as compromised fertility, type 2 diabetes, obesity, hypertension, and respiratory dysfunction.209 Nicotine also can be found in the breast milk of smokers and therefore may continue to act on infant development after birth.209 Given that some ECIGs are capable of meeting or in some cases exceeding the nicotine delivery of combustible cigarettes, these effects are of critical public health concern, particularly for cigarette-smoking mothers who might consider ECIGs as an alternative to tobacco cigarettes in a belief that they are eliminating risks to the fetus.210

Adolescence is a period of behavioral change that reflects structural and neurochemical changes in the CNS.208 Nicotine administration can influence these developmental changes through a variety of mechanisms, and preclinical work suggests that chronic nicotine exposure during adolescence can downregulate certain nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes and alter serotonergic receptor function in ways that can be long lasting, and may also influence dopaminergic activity.208 These effects of chronic nicotine administration in the CNS can increase the rewarding effects of other drugs of abuse, contribute to attention and cognitive deficits, and exacerbate mood disorders.208 Overall, nicotine, even at low doses, has demonstrable long-term effects on the adolescent brain, suggesting cause for concern for the dramatic rise of ECIG use among adolescents in the United States and elsewhere (Fig. 3).

Summary

The literature regarding the effects of ECIGs on various body systems is sparse and is marked by a lack of standardization in methods. Nonetheless, there are some indicators that ECIG aerosols are not benign, especially with respect to body systems that are sensitive to nicotine effects. Developing standardized methods for ECIG aerosol generation may be a prerequisite to valid and reliable preclinical studies, and identifying relevant health-effect biomarkers and developing standardized instruments for assessing ECIG-induced nicotine dependence are both important goals for clinical work.

ECIG effects on tobacco cigarette smoking

There is some controversy regarding the role of ECIGs in cigarette-smoking cessation.13,211,212 A variety of methods might be used to add evidence to this discussion, including survey studies and experimental work, including randomized control trials (RCTs).

Survey methods

A number of survey studies have been conducted examining the relationships between ECIGs and combustible tobacco use, specifically in regard to smoking cessation and tobacco cigarette consumption (Table S2). Some have found a significant relationship between ECIG use and increased incidence of combustible tobacco cessation.202,213–221 Others have found an increased likelihood of cessation attempts with no effect on actual long-term cessation.222,223 Furthermore, many studies have reported no association between ECIG use and combustible tobacco cessation.219,224–232 The association between ECIGs and the number of cigarettes smoked per day has also been explored. While two studies reported that ECIGs had no effect on the number of cigarettes smoked per day,224,228 others reported a decreased number of cigarettes smoked per day.202,215,220,221,225,233,234

Relationships between ECIGs and prior combustible tobacco cessation attempts, intention to quit smoking via the use of ECIGs, and the belief that ECIGs are helpful aids for smoking cessation have also been examined. While it has been reported that ECIG users do not differ in prior quit attempts compared to nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) users,235 others have found that NRT users made more prior quit attempts and had greater motivations to quit compared to ECIG users.236 Others have found that current ECIG users report an increased incidence of prior quit attempts compared to cigarette smokers227,237–239 and NRT users.237 A study using a sample of homeless individuals between the ages of 13 and 25 reported that ECIG users had no intention to quit smoking combustible tobacco in the future,240 whereas another study with individuals in grades 6–12 who were cigarette smokers reported no relationship in either direction between ECIG use and future quitting behavior nor an effect on recent quit attempts.89 A number of studies with adult samples reported a significant positive relationship between ECIG use and increased intention to quit smoking combustible tobacco or to use ECIGs to aid in quitting.231,238,239,241 Studies also reported that physicians believe ECIGs are helpful cessation aids242 or that participants reported that their providers endorsed the use of ECIGs for cessation.113 Unfortunately, the tendency to treat all ECIG device/liquid combinations as similar when they likely differ in terms of nicotine delivery to the user complicates the interpretation of these results and may account for cross-study differences.

Experimental/clinical trial methods

The effects of ECIGs on tobacco cigarette cessation–related outcomes using uncontrolled cohort study designs have been examined. They show that, among individuals motivated or unmotivated to quit, 10–50% who used nicotine-containing ECIGs stopped smoking during follow-up periods of 6–24 months postbaseline (e.g., Refs. 215 and 243–247) This work should be interpreted cautiously owing to a lack of experimental controls and the use of devices with uncertain-nicotine delivery profile. Some of these limitations could be addressed by using RCT methods. To date, two published studies used RCT methods to examine the effect of ECIG use on smoking cessation244,248 and on the effects of ECIGs on cigarette consumption.249 In the first RCT,244 tobacco cigarette smokers with no intention to quit were randomized to one of three double-blind ECIG conditions for 12 weeks: 7.2 mg/mL nicotine concentration for all 12 weeks (n = 100), 7.2 mg/mL nicotine concentration for 6 weeks followed by 5.4 mg/mL nicotine concentration for weeks 7–12 (n = 100), or placebo ECIG for all 12 weeks (n = 100). Significant decreases were reported in cigarettes smoked per day and expired breath carbon monoxide (CO) levels at study visits compared to baseline, but no consistent differences were observed across the ECIG conditions during the study, indicating no effect of ECIG nicotine content. Overall, over 20% of the sample reduced their smoking by week 12, with 10% reporting a reduction at the 52-week follow-up. Approximately 10% of the entire sample ceased all combustible tobacco use during the study.

Another RCT examined the effectiveness of ECIGs in maintaining tobacco abstinence compared to nicotine patches among tobacco cigarette smokers who were motivated to quit.248 Smokers were randomized to a nicotine patch (n = 295), an active ECIG (16 mg/mL; n = 289), or a placebo ECIG (n = 73). Approximately 7% of those randomized to the active ECIG condition were verified as abstinent from smoking at 6 months, compared to 6% in the nicotine patch condition and 4% in the placebo ECIG condition. There were no significant differences in abstinence rates between the active ECIG and nicotine patch conditions.248

A third, much smaller RCT used open ECIG models with 18-mg/mL nicotine liquid to examine the effects of the ECIG on cigarette consumption among long-term smokers with no immediate motivation to quit.249 Two ECIG groups were instructed to use an ECIG with 18 mg/mL liquid nicotine, during and between laboratory sessions ad lib, with one group using a 3.3-V, 2.2-Ω device (n = 16), another using a 3.7-V, 2.5-Ω device (n = 16) and a control group receiving no ECIG (n = 16). At the end of an 8-week evaluation period, a significant reduction in cigarette intake was observed for the two ECIG conditions but not the control condition; a similar effect was observed for expired air CO concentration.249 This study also involved longer-term follow-up, but after 8 weeks all participants had been given an ECIG device/liquid combination to use.249

The small effect size of nicotine-containing ECIGs on smoking cessation rates in the two cessation-focused RCTs244,248 may reflect the nicotine delivery of the ECIG device/liquid used therein. Indeed, in one of the two trials,248 ECIG nicotine delivery was tested in four subjects who were among those initially randomized to the ECIG condition, and results indicated minimal nicotine delivery.248 There is a logical argument to be made that the extent to which a given ECIG device/liquid combination is likely to help smokers quit tobacco cigarettes depends upon the ability of that device/liquid combination to deliver nicotine as effectively as a combustible tobacco cigarette. If valid, this argument suggests that future RCTs examining ECIG effects on smoking cessation should include device/liquid combinations known to deliver nicotine as effectively as a combustible cigarette.250

Effect of ECIGs on initiation of nicotine use/dependence

Another relevant issue is whether nicotine-naive individuals experiment with ECIGs and eventually develop dependence, perhaps by first using device/liquid combinations that deliver very little nicotine.250,251 Potentially, some users might also transition to combustible tobacco use following ECIG use. This latter issue has been explored in at least two published studies, one in adolescents252 and the other in young adults.253 Data from the U.S. National Youth Tobacco Survey suggest that, among middle and high school students, having ever used ECIGs is correlated with intention to smoke combustible tobacco cigarettes in this population (OR = 1.7, 95% CI 1.2–2.3).252 Similarly, data from the U.S. National Adult Tobacco Survey show that having ever used ECIGs among 18- to 29-year-olds was correlated with openness to combustible cigarette smoking (OR = 2.4; 95% CI 1.7–3.3).253 More systematic evidence is needed to determine the strength and reliability of this relationship. For example, there is urgent need for longitudinal studies in which the behavioral patterns of non–cigarette-smoking adolescents and adults are studied over time to determine the extent to which they initiate ECIG use, which ECIG device/liquid combinations they are using, how their use of ECIG device/liquid combinations changes over time, the extent to which those ECIG device/liquid combinations initiate and maintain nicotine dependence, and whether ECIG use in this population facilitates a transition to combustible or other tobacco product use. These longitudinal studies could also examine other possible factors that could be related to nicotine/tobacco use in these potentially vulnerable populations.

Adverse events associated with ECIGs

Several published articles highlighted ECIG-associated poisonings, with reports related to data collected from poison control centers showing a rapid increase in calls received254–262 and emergency department case reports.260–262 There has been an increase in the number of calls to poison control centers, with many of the patients being young children.254,255,257–259 Oral ingestion, dermal, inhalation, and ocular exposures were the primary routes of exposure reported.254,255,257–259 Compared to cigarette-exposure calls, ECIG-related calls were more likely to report an adverse event, with those most commonly reported related to nicotine toxicity, including vomiting, nausea, and eye irritation.255 Across all studies, symptoms ranged from mild to moderate, appearing to be related to acute nicotine toxicity, with very few reports of serious adverse events involving hospitalization.254,255,257–259 Emergency department case reports presented similar findings with children, and also called for increased public education, including among physicians, as well as regulatory efforts to curtail these occurrences.260,261 There have also been reports of the use of ECIG liquids in suicide attempts263 with at least two fatalities, one by oral administration of a liquid containing 72 mg/mL nicotine264 and the other by intravenous injection of an unspecified product.262 The Center for Tobacco Products at the FDA has also fielded complaints regarding adverse events related to ECIG use, some of which have been severe, including pneumonia, congestive heart failure, and burns to the face from device explosions.265 Finally, adverse effects have also been reported in some non-users (from passive aerosol exposure).266

Other health effects

A number of case reports suggest some ECIG-related health problems, including recurring ulcerative colitis,267 lipoid pneumonia,268 acute eosinophilic pneumonitis,269 subacute bronchial toxicity,270 reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome,271 and reversal of chronic idiopathic neutrophilia.272 Other studies report potential lower health risk, including decreased exposures to carcinogens in ECIG users as compared to combustible cigarette smokers.273 One small-sample study (n = 14; 270) suggested that ECIG use does not influence symptoms of schizophrenia,274 while another (n = 18)233 suggested that ECIG use improves outcomes in asthmatic combustible cigarette smokers, with no reports of serious adverse events. Finally, in addition to decreased carboxyhemoglobin and increased oxygen saturation, 13 participants in a within-subject design reported improvements in taste, appetite, and sense of smell and less phlegm when using an ECIG over a 2-week period.275

Discussion

The research reviewed here demonstrates clearly that ECIGs are a diverse and evolving class of products that produce an aerosol that, under at least some conditions, depending on device power, liquid ingredients, and user behavior, can emit the dependence-producing drug nicotine, as well as other toxicants (e.g., Refs. 25, 33, 40, 41, and 276). Use of these products is increasing in the United States and worldwide, with particularly dramatic increases in prevalence among adolescents and young adults;7,136,139 some individuals who report ECIG use may be otherwise nicotine naive108 and also may be at increased risk for future initiation of tobacco cigarette smoking.252 The potential health effects of the aerosol emitted by ECIGs are only beginning to be understood, but may include effects on the respiratory42,163 and immunologic systems.183 The nicotine contained in the aerosol can influence the cardiovascular system174 and may well support some level of dependence in cigarette smokers who use ECIGs.196,197 There are some data that address the concern that ECIG-delivered nicotine engenders dependence in non-smokers who begin using ECIGs and may also influence fetal development in pregnant users or brain development in adolescent users. However, there is ample evidence that ECIG-emitted nicotine is delivered to the user (e.g., Refs. 190, 277, and 278), and in some cases users can achieve plasma nicotine concentrations immediately after 10 puffs that are similar to those seen immediately after 10 puffs from a combustible tobacco cigarette.187 The survey literature regarding the influence of ECIG use as a means to eliminate tobacco cigarette smoking is mixed, with some longitudinal studies reporting a cessation effect (e.g., Ref. 213) while others do not.222 The observational methods used are susceptible to a variety of biases247 that add to the challenge of interpreting them in toto. Individual RCT results indicate that ECIGs can be at least as effective as nicotine patches at increasing cessation rates;248 a Cochrane review noted a “small” effect size and an overall “low or very low” quality of evidence, due to the few trials addressing this issue.247

Importantly, the scientific literature regarding all of these issues, while growing, has been largely limited to studies of single device/liquid combinations where the aerosol is produced under tightly constrained conditions that may or may not resemble actual user behavior. Given the variety of devices and their ongoing evolution, this observation is perhaps not surprising, but nonetheless is a challenge to the field. There is an urgent need to develop tools for the systematic evaluation of ECIG aerosol content, its effects in in vitro and in vivo preparations, and the delivery of constituents to users. In this respect, the report of a mathematical model that predicts ECIG nicotine emissions accurately based on inputs that account for device characteristics, liquid ingredients, and user behavior25 is an important development. That is, the model allows researchers to understand the nicotine yield of virtually any device and may therefore help to generalize results from a single device to all others with similar design characteristics and liquid ingredients. Of course, the current model is limited to emitted nicotine, and more work is needed to relate ECIG nicotine emissions to actual nicotine user exposure, as well as to determine if other toxicant emissions can be predicted in this manner.

Epidemiologic studies assessing ECIG use prevalence and effects on smoking cessation, reduction, and other health outcomes are also challenged by an ongoing need for systematic investigation. Interpreting the results of future studies would be enhanced greatly by a more thorough assessment of what device/liquid combinations respondents are using (as that can influence nicotine and other toxicant exposure) as well as the frequency of use. For example, the current literature that reports mixed effects of ECIGs on smoking cessation and reduction may be influenced considerably by the fact that some users within and across studies may be using device/liquid combinations that deliver virtually no nicotine, while others may be using combinations that deliver nicotine as effectively as a tobacco cigarette. This source of variability might be controlled by obtaining details concerning device/liquid combinations via self-report and/or more innovative methods such as user photographs that are uploaded with survey responses. Photographs of identifying information for device and liquid can lead to a greater understanding of device power and liquid ingredients that can help explain the variability in study results. In fact, this method of data collection has already been validated in other research domains.279 With respect to ECIG use frequency, the use patterns of ECIG users may not be identified as easily as those of cigarette smokers, who can differentiate one use bout from another, and count use bouts, based on the number of cigarettes smoked over a period of time. Again, innovative methods may be required, including developing standardized operational definitions for a use bout, assessing nicotine liquid consumption per unit time, using puff counters integrated into devices, and developing ambulatory puff topography instrumentation, as has been done for cigarettes.76

This review identified very few RCTs that assessed ECIG effects on cessation and other outcomes, and those trials likely used ECIGs that delivered nicotine ineffectively relative to a tobacco cigarette.248 While RCTs are conducted under relatively idealized conditions, they offer an advantage over observational designs in that, with stratification and other methods, they can provide experimental control over potentially relevant sources of variability, such as participant dependence level and number of previous quit attempts. There is an urgent need for more controlled trials that take these sources of variability into account while also using well-characterized device/liquid combinations that can be expected to deliver nicotine to cigarette-smoking participants as effectively as a combustible cigarette every time that they use the product.

Finally, an area of great concern is the rapid rise in use of ECIGs, even if it only reflects occasional use, among adolescents (Fig. 3). This rise may be due to in part to targeted marketing that includes advertisements, sponsorships, and social media,127,280–282 not to mention an array of attractive flavors that mimic those of candies, desserts, and alcoholic and non-alcoholic beverages.283 At least in the United States, a large proportion of ECIG advertisements focus on closed systems,127 at least some of which deliver very little nicotine to the user.174 For some commentators,250,251 this marketing strategy recalls the smokeless tobacco “starter products” that delivered nicotine inefficiently and thus allowed nicotine-naïe individuals to begin using tobacco without experiencing drug-mediated adverse side effects, and allowed them to “graduate” to higher nicotine products as drug tolerance developed.284 If applied to ECIGs, such a strategy could lead adolescents who are otherwise nicotine naive toward nicotine dependence, with all the risks that entails for the developing brain,208 as well as the psychological and behavioral sequelae that can accompany addictive disorders.251 Clearly, there is a need to learn about these issues, and a strong rationale for an empirically based regulatory approach toward ECIGs that balances any potential ECIG-mediated decreases in health risks for smokers who use them as a substitute for tobacco cigarettes and against any increased risks for nonsmokers who may be attracted to used.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Parts of an open electronic cigarette system.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Tamara Hudson, Hannah Mayberry, and Kathleen Osei for their help with figures and formatting references. This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P50DA036105 and the Center for Tobacco Products of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NIH or the FDA.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jamal A, Agaku IT, O’Connor E, et al. Current cigarette smoking among adults—United States, 2005–2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63(47):1108–1112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2001—2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2011;60(44):1513–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carter BD, Abnet CC, Feskanich D, et al. Smoking and mortality—beyond established causes. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372(7):631–640. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1407211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Giovino GA, Schooley MW, Zhu BP, et al. Surveillance for selected tobacco-use behaviors–United States, 1900–1994. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. CDC surveillance summaries/Centers for Disease Control. 1994;43(3):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings KM, Proctor RN. The changing public image of smoking in the United States: 1964–2014. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2014;23(1):32–36. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arrazola RA, Neff LJ, Kennedy SM, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students—United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2014;63(45):1021–1026. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bonnie RJ, editor. Ending the Tobacco Problem: A Blueprint for the Nation. National Academies Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malone R, McDaniel P, Smith E. It is time to plan the tobacco endgame. BMJ. 2014;348 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Warner KE. An endgame for tobacco? Tobacco control. 2013;22(suppl 1):i3–i5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-050989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abrams DB. Promise and peril of e-cigarettes: can disruptive technology make cigarettes obsolete? JAMA. 2014;311(2):135–136. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.285347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Etter JF. Should electronic cigarettes be as freely available as tobacco? Yes. BMJ. 2013;346 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f3845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes have a potential for huge public health benefit. BMC Medicine. 2014;12(1):225. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hon L. 2518174 A1 Patent No. 2003 inventor.

- 15.Sottera, Inc v. FDA, 627 F.3d 891 (D.C. Cir. 2010)

- 16.Breland AB, Spindle T, Weaver M, et al. Science and Electronic Cigarettes: current Data, Future Needs. J Addict Med. 2014;8:223. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hajek P, Etter JF, Benowitz N, et al. Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1801–1810. doi: 10.1111/add.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisinger C, Døssing M. A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes. Preventive Medicine. 2014;69:248–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vansickel AR, Cobb CO, Weaver MF, et al. A clinical laboratory model for evaluating the acute effects of electronic “cigarettes”: nicotine delivery profile and cardiovascular and subjective effects. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2010;19(8):1945–1953. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bullen C, McRobbie H, Thornley S, et al. Effect of an electronic nicotine delivery device (e cigarette) on desire to smoke and withdrawal, user preferences and nicotine delivery: randomised cross-over trial. Tobacco Control. 2010;19(2):98–103. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.031567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dawkins L, Turner J, Hasna S, Soar K. The electronic-cigarette: effects on desire to smoke, withdrawal symptoms and cognition. Addictive behaviors. 2012;37(8):970–973. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adkison SE, O’Connor RJ, Bansal-Travers M, et al. Electronic nicotine delivery systems: international tobacco control four-country survey. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44(3):207–15. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gravely S, Fong GT, Cummings KM, et al. Awareness, Trial, and Current Use of Electronic Cigarettes in 10 Countries: Findings from the ITC Project. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:11691–11704. doi: 10.3390/ijerph111111691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King BA, Alam S, Promoff G, Arrazola R, Dube SR. Awareness and ever-use of electronic cigarettes among US adults, 2010–2011. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2013;15(9):1623–1627. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Talih SZ, Balhas T, Eissenberg R, et al. Effects of User Puff Topography, Device Voltage, and Liquid Nicotine Concentration on Electronic Cigarette Nicotine Yield: Measurements and Model Predictions. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2015a;17(2):150–157. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costigan S, Meredith C. An approach to ingredient screening and toxicological risk assessment of flavours in e-liquids. Regul Toxicol Pharm. 2015;72(2):361–369. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2015.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tierney PA, C D, Karpinski JE, Brown W, et al. Flavour chemicals in electronic cigarette fluids. Tobacco Control. 2015 doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tayyarah R, Long GA. Comparison of select analytes in aerosol from e-cigarettes with smoke from conventional cigarettes and with ambient air. Regul Toxicol Pharm. 2014;70(3):704–710. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2014.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varlet V, Farsalinos K, Augsburger M, et al. Toxicity assessment of refill liquids for electronic cigarettes. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2015;12(5):4796. doi: 10.3390/ijerph120504796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng T. Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes. Tobacco Control. 2014;23(suppl 2):ii11–ii17. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uchiyama S, Ohta K, Inaba Y, et al. Determination of carbonyl compounds generated from the e-cigarette using coupled silica cartridges impregnated with hydroquinone and 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine, followed by high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Sci. 2013;29(12):1219–1222. doi: 10.2116/analsci.29.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosmider L, Sobczak A, Fik M, et al. Carbonyl Compounds in Electronic Cigarette Vapors: Effects of Nicotine Solvent and Battery Output Voltage. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2014;16(10):1319–1326. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen RP, Luo W, Pankow JF, et al. Hidden formaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosols. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):392–394. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1413069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nitzkin JL, Farsalinos K, Siegel M. More on hidden formaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosols [Letter to the editor] The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:1575–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1502242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thompson RH, Lewis PM. More on hidden formaldehyde in e-cigarette aerosols [Letter to the editor] The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:1575–1577. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1502242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]