Abstract

Metabolome analysis is used to evaluate the characteristics and interactions of low molecular weight metabolites under a specific set of conditions. In cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatotic hepatitis (NASH) the liver does not function thoroughly due to long-term damage. Unfortunately the early detection of cirrhosis, HCC, NAFLD and NASH is a clinical problem and determining a sensitive, specific and predictive novel method based on biomarker discovery is an important task. On the other hand, metabolomics has been reported as a new and powerful technology in biomarker discovery and dynamic field that cause global comprehension of system biology. In this review, it has been collected a heterogeneous set of metabolomics published studies to discovery of biomarkers in researches to introduce diagnostic biomarkers for early detection and the choice of patient-specific therapies.

Key Words: Cirrhosis, HCC, NAFLD, NASH, Metabolomics

Introduction

Hepatic diseases are considered as the liver damage. The diagnostic confirmation of hepatic disease is based on a histological examination or combined results of clinical and imaging examinations (1). Clinical tests include the presence of enzymes in the blood such as alanine transaminase, aspartate transaminase assessment of serum proteins as like serum albumin and serum globulin, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time and platelet count (2). However, the mentioned methods cannot be satisfactorily applied to a clinical diagnosis. Not only long time is needed to achieve clinical results, but also blind spots in imaging studies is that they cannot get sensitive diagnoses (3). The liver biopsy is a standard, and an invasive approach to diagnose liver diseases. The early and non-invasive diagnosis of hepatic diseases is a challenging task for the clinician. Considerable efforts have been made to find sensitive and specific predictive markers (4). New techniques and non-invasive diagnostic methods solve these limitations and can be helpful in the early stage diagnosis and may eliminate the requirement for biopsy in patients. Metabolomics, with other omics technologies help detailed understanding of biochemical viral events inside the cell and relationships with each other in the systems biology approach (5-11). Some Metabolomic studies have been reported in biomarker discovery on various diseases in recent years (12-20). Metabolomics is the study of all metabolites with low molecular weight in quantitative scale in unit time under specific environmental conditions in an organism or biological sample. Peptide, alkaloids, nucleic acids, amino acids, organic acids, carbohydrates, vitamins, and polyphenols have been introduced as small-molecule (<1000 Da) in a cell, tissue or organism (21). Metabolomics is reported as a new powerful technology in biomarker discovery and dynamic field that cause global comprehension of biological systems similar to proteomics, transcriptomics and genomics. It is essential to distinguish between diseased and non-diseased status information (22). Obtained results from metabolomic studies have suggested that metabolomic profiles may have the potential for application in the field of disease diagnosis (23, 24) or identification of disease biomarkers (25). Commonly applied techniques in metabolomic analysis are mass spectrometry (MS)-based techniques, including: gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS), liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (LC/MS), nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (26, 27). In this review, a brief expression and interpretation about metabolomics studies and its achievements in biomarker discovery of liver diseases are presented. Then, a number of metabolic studies are described that using diverse biological specimens for various types of hepatic diseases including, cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatotic hepatitis (NASH).

Metabolomics applications in liver diseases

Early diagnosis of liver diseases is a problem and an obstacle to achieve the best therapy of liver diseases for the clinician. Therefore, non-invasive and simple tests are needed. Metabolomics has been introduced as a way for finding effective diagnostic markers in earlier detection (4). Herein, some published metabolic studies for several liver diseases, including, cirrhosis, HCC, NAFLD and NASH is discussed.

Cirrhosis

Liver cirrhosis is a major cause of global health loss, with more than one million deaths in 2010 (28). In cirrhosis, most patients during early disease don’t show specific symptoms of disease and so they may loss in- time therapy. Because, the changes resulting from bridging fibrosis are compensated by liver for this stage of disease. In addition, patients do not show specific symptoms until they enter the stage of decompensation (29). The most important factors for development of cirrhosis are NASH, hepatitis B and C, as well as alcohol consumption. The early diagnosis of cirrhosis is a problem for the clinician and it has been afforded to present sensitive, specific and predictive novel biomarkers that can identify and detect early stage of disease. Actualizing the discovery of biomarkers, new techniques such as metabolomics help to achieve this goal. Some important metabolites in cirrhosis are tabulated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of recent metabolomic studies in the field of cirrhosis

| Author and year | Biological specimens |

Technological Platform used |

Decreased or increased metabolites in the patients compared to the control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qi S-W (2012) | serum | NMR | cirrhotic patients vs healthy controls: glucose, lactate lipid , choline decompensated cirrhosis vs. compensated : pyruvate, phenylalanine, succinate, lysine, histidine, glutamine, alanine, glutamate, creatine acetone , LDL and VLDL |

| Xue R(2009) | Serum | GC/MS | Glucose, Butanoic acid, Hexanoic acid, Serine, Valine, Urea, Isoleucine, Proline, Galactose , Acetic acid, sorbitol |

| Gao H(2009) | Serum | NMR | Low-density lipoproteins Isoleucine Leucine Valine pyruvate Acetoacetate Choline Unsaturated lipid Acetate N-acetylglycoproteins Glutamine ketoglutarate Taurine Glycerol Tyrosine 1-methylhistidine Phenylalanine |

| Fitian AI(2014) | Serum | GC/MS and UPLC/MS-MS | Azelate Undecanedioate 2-hydroxyglutarate Hexadecanedioate Taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDCA) Taurocholate (TCA) Taurocholenate sulphate Glycohyocholate Glycocholate(GCA) Tauroursodeoxycholate Glycochenodeoxycholate (GCDCA) Taurolithocholate 3-sulphate Phenethylamine 1-stearoylqlycerophosphocholine ,glycerophospholipid classes, the glycerophosphoethanolamines and the glycerophosphocholines |

| Yang T(2014) | Serum | UPLC-MS | 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) alanine, valin, leucin, phenylalanine, tryptophan prolin, serin, glutamin, histidin, arginine tyrosin,glycochenodeoxycholic acid,taurocholic acid,taurodeoxycholic acid,glycochenodeoxy cholic acid,glycoursodeoxycholic acid |

| Lin X(2011) | Serum | GC/MS | arachidonic acid, cholesterol, ratio of stearic acid to oleic acid,glutamic acid aspartic acid |

| Shao Y(2014) | urine | LC–QTRAP MS | CIR and HCC vs. controls: MTA -deoxy-5-methylthioadenosine and 6-methyladenosinie CIR vs HCC: xanthine, hydroxyphenyllactic acid, L-3-phenyllactic acid, and 1-ribosyl-N-ω-valerylhistamine |

| Dai W(2014) | urine | LC-MS | steroid hormone |

| MartínezGranados B(2011) | Liver tissue | NMR | Phosphocholine, Phosphoethanolamine, Glutamate Glutamine, Aspartate ,ß-glucose, unsaturated fatty acids ,free Choline |

Red color: increased metabolite

Blue color: decreased metabolite

Investigations on serum metabolic profiling of hepatic cirrhosis by Su-Wen Qi, et al. analyzed metabolites by Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for compensated cirrhosis patients (n = 30), decompensated cirrhosis patients (n = 30) and healthy controls (n = 30).

Compared with compensated liver cirrhosis (LC) patients, the decompensated LC patients displayed higher levels of pyruvate, phenylalanine, succinate, lysine, histidine, glutamine, alanine, glutamate, creatine and lower levels of acetone, as well as LDL and VLDL. The serum metabolic profiling of cirrhotic patients compared with healthy controls showed decreased levels of lipids and choline, as well as increased levels of glucose and lactate (3).

Metabolome analysis of plasma was undertaken using NMR in groups of LC and HCC sera detected plasma metabolic profile. Sera metabolomic analysis of healthy humans versus LC and HCC has been shown higher levels of glutamine, Nacetylglycoproteins,acetate, alpha-ketoglutarate, tyrosine,glycerol, 1-methylhistidine and phenylalanine, as well as lower levels of low-density lipoprotein, isoleucine, valine, pyruvate, acetoacetate, creatine, choline and unsaturated lipids (30). Serum metabolic profiling by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS) (Ruyi Xue and colleagues) in hepatite B virus (HBV) infected non-cirrhosis male subjects (n=20) and HBV infected cirrhosis male patients (n=20) showed that glucose, acetic acid, hexanoic acid, D-glucitol, butanoic acid, D-lactic acid, phosphoric acid, 1-naphthalenamine and sorbitol are potential serum biomarkers for HBV infected cirrhosis diagnosis (31). Another investigation on serum metabolomic profiles of cirrhosis and HCC patients using GC/MS and ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC)/MS-MS showed that bile acids and dicarboxylic acids are elevated in cirrhosis. Important pathways for cirrhosis were bile acid metabolism, acylcarnitine metabolism, dicarboxylic fatty acid metabolism, fibrinogen peptide cleavage cascades, haemoglobin catabolism and dipeptide metabolism (details are presented in table 1) (32).

In one study, UPLC-MS is used to analyze the metabolome profile in patients with liver cirrhotic ascites versus healthy controls. Results showed that 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT), 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA), valin, alanine, leucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan prolin, serine, glutamin, arginine and histidin were remarkably reduced in patients with liver cirrhotic ascites. Tyrosin, glycochenodeoxycholic acid, taurocholic acid, taurodeoxycholic acid, glycoursodeoxycholic, glycochenodeoxy cholic acid, and the ratio of branched amino acid /aromatic amino acid (BCAA/AAA) were significantly increased in these patients. The lysophosphatidylcholines C16: 1, C18: 0 and C18: 2 were suggested as potential biomarkers in patients with liver cirrhosis (33).

Down-regulation of the ratio of stearic acid to oleic acid in liver cancer and cirrhosis patients was reported. It is additionally found that the content of arachidonic acid (AA) is remarkably lower in the plasma of patients with hepatitis, cirrhosis and liver cancer relative to controls. The levels of cholesterol in cirrhosis are obviously lower than controls while are stable in hepatitis and liver cancer. This phenomenon might indicate the metabolic disorder of lipoprotein in cirrhosis cases. Glutamic acid decreases significantly in all three types of liver diseases (cirrhosis, HCC, hepatitis), while aspartic acid increases markedly in cirrhosis and liver cancer (34).

In another study, potential biomarkers of liver cirrhosis have been reported such as glycocholic acid, glycochenodeoxycholic acid, taurocholic acid, taurochenodesoxycholic acid, and LPCs (35).

Recently, urinary experiment based on liquid chromatography identified potential metabolite biomarkers with comparing 21 CIR cases versus 33 HCC cases and 26 healthy individuals. HCC versus CIR show a significant increase in cyclic AMP, adenosine and several medium-chain acylcarnitines. While, CIR and HCC patients compared with controls show the elevated MTA -deoxy-5-methylthioadenosine and 6-methyladenosinie. Four metabolites including xanthine, L-3-phenyllactic acid, 1-ribosyl-N-ω-valerylhistamine and hydroxyphenyllactic acid had higher urinary levels in the CIR group relative to HCC group. Several markers have been introduced for distinguishing HCC from cirrhosis. For example , carnitine C4:0 and hydantoin-5-propionic acid have been suggested as a combinational marker to discern HCC from CIR. (36).In same way Dai W, et al. found that epitestosterone and allotetrahydrocortisol have a favorable capacity to distinguish HCC from CIR.

Even though there may be common conditions between HCC and cirrhosis such as decreasing urinary steroid hormone pattern in cirrhotic and early HCC patients that was reported (37).

A few studies have explained metabolome of the hepatic tissue liver for cirrhosis (38). In the compression of cirrhotic tissue with non-cirrhotic tissue, free choline was found to be lower in cirrhotic tissue relative to non-cirrhotic tissue, whereas the amounts of phosphocholine and phosphoethanolamine were found to increase. There were also significant variations between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic samples in some amino acids. In cirrhosis, glutamine and aspartame were decreased, whereas the levels of glutamate were increased. Other identified metabolites with statistically significant decreases between cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic samples include glucose and some unsaturated fatty acids.

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third reason of mortality by origin of cancer (39). One of the most primary factors for the poor survival of patients is a late diagnosis of HCC. Thereby, it is important to find sensitive and specific biomarkers for early diagnosis of HCC in medicine (40).

Metabomic studies provided a suggestion that metabolites are powerful and promising elements for identifying novel biomarkers of HCC (41). It has been reported identification of the potential metabolite biomarkers between high-grade HCC tumors versus low-grade HCC tumors. This research showed increased levels of lactate, leucine ,glutamine, glutamate, glycine, alanine, choline and phosphorylethanolamine (PE) as well as decreased levels of glucose, PC, GPC, triglycerides and glycogen in high-grade HCC (42). Meanwhile, Fitian A and colleagues reported that HCC is related to elevated levels of γ-glutamyl oxidative stress-associated metabolites, hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (12-HETE, 15-HETE), sphingosine, xanthine, amino acids serine, glycine and aspartate(32).

Another study introduced dihydrosphingosine and phytosphingosine as potential and diagnostic biomarkers of HCC with compression of hepatitis Binduced liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma's metabolome (details are shown in table 2) (35). In another study, metabolomic profiles were investigated in sera and urine of HCC (n = 82), benign liver tumor patients (n = 24) and healthy controls (n = 71). The differential metabolites are presented in table 2. Histidine and inosine are two statistical significant metabolites for HCC (43).

Table 2.

Summary of recent metabolomic studies in the field of HCC

| Author and year | Biological specimens |

Technological Platform used |

Decreased or increased metabolites in the patients compared to the control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gao H (2009) | serum | NMR | Acetate, pyruvate, glutamine, glycerol, tyrosine, phenylalanine alpha-ketoglutarate, 1-methylhistidine LDL, VLDL, valine, acetoacetate, choline, taurine, "unsaturated lipid" |

| Fitian AI (2014) | serum | GC/MS UPLC/MS-MS | HCC vs. cirrhosis: 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE), 15-HETE, sphingosine, γ-glutamyl oxidative stress-associated metabolites, xanthine, amino acids, serine, glycine , aspartate , a-cylcarnitines HCC vs. controls: Azelate, Taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDCA) Taurocholate (TCA), Taurolithocholate 3-sulfate, Grycocholate (GCA) Tauroursodeoxycholate (TDCA) Grycochenodeoxycholate (GDCA) Undecanedioate Sebacate (decanedioate) |

| Yang Y(2007) | liver | NMR | High-grade HCC vs. low-grade HCC tumors: lactate, leucine glutamine, glutamate, glycine and alanine, choline and phosphorylethanolamine (PE) glucose,PC, GPC, triglycerides and glycogen |

| Yin P(2009) | serum | HPLCESITOFMS | TCA, GCA, bilirubin, TCDCA, GCDCA, carnitine, acetylcarnitine Hypoxanthine, phytosphingosine, dihydrosphingosine, LPC(18:2), LPC(18:3), LPC(16:1), LPC(18:0), taurine, 6-methyl-nicotinic acid |

| Chen T(2011) | serum /urine | UPLCESIQTOFMS and GCTOFMS |

Serum:

carnitine, GCDCA, GCA, cysteine, 2-oxoglutarate, lactate, pyruvate, inosine, erythronate, Urine: GCA, dopamine, adenosine, xanthine, phenylalanine, dihydrouracil, hypotaurine, threonine, N acetylneuraminic acid Serum: glycerol, glycine, serine, aspartate,citrulline, tryptophan, lysine, glucosamine, phenylalanine, β-alanine, glycerate, arabinose, creatinine, phosphate, O-Phospho-l-serine Urine: normetanephrine, Cysteine, TMAO, adenine, cysteic acid, 6-aminohexanoate, creatine |

| Patterson AD(2011) | plasma | UPLCESIQTOFMS | glycodeoxycholate, deoxycholate 3-sulfate, bilirubin,fetal bile acids 7α-hydroxy-3-oxochol-4-en-24-oic acid and 3-oxochol-4,6-dien-24-oil LPC(20:4), LPC(22:6)LPC(14:0), LPC(16:0), LPC(20:2), LPC(18:0) LPC(18:1), LPC(18:2), LPC(20:5), LPC(18:3), LPC(20:3) |

| Wang B(2012) | serum | UPLCESIQTOFMS | GCDCA , Canavaninosuccinate, phenylalanine, PC(16:0/22:6, LPC(16:0), LPC(18:0), PC(18:0/18:2), PC(16:0)/20:4) |

| Ressom HW (2012) | serum | UPLCESIQTOFMS | lysophosphatidylcholine (lysoPC 17:0) glycochenodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate (3-sulfo-GCDCA), glycocholic acid (GCA), glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), taurocholic acid (TCA), and taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDCA) |

| Xiao JF | serum | UPLCESIQTOFMS | PhePhe TCDCA, GDCA, 3β, 6β-dihydroxy-5β-cholan-24-oic acid, oleyol carnitine |

| Zhang A | urine | UPLCESIQTOFMS GCA |

GCA |

| Nahon P(2012) | serum | NMR | Glutamate, acetate ,N-acetyl glycoprotein Glutamine |

| Budhu A(2013) | liver | GCMS | monounsaturated palmitic acid |

| Beyoğlu D(2013) | liver | GCMS | glucose, glycerol 3- and 2-phosphate, malate, alanine, myo-inositol, and linoleic acid glycolysis, attenuated mitochondrial oxidation, and arachidonic acid synthesis |

| Chen F(2011) | serum | UPLCESITQMS | 1-Methyladenosine |

| Shariff MI, (2011) | urine | NMR | Creatine, Carnitine Glycine, TMAO, Hippurate, Citrate, Creatinine |

| Wu H(2009) | urine | GCMS | xylitol and urea elevated. |

| Yang J(2004) | urine | HPLC | pseudouridine, 1-methyladenosine, xanthosine, 1-methylinosine, 1- and 2-methylguanosine, N4-acetylcytidine, adenosine |

| Chen J(2009) | urine | HILIC RPLC MS | Hypoxanthine, Proline betain, Acetyl carnitine, Carnitine, Phenylacetylglutamine Carnitine C9:1, Carnitine C10:3, Butylcarnitine |

Red color: increased metabolite

Blue color: decreased metabolite

Patterson, et al. found that plasma levels of fetal bile acids, 7α-hydroxy-3-oxochol-4-en-24-oic acid and 3-oxochol-4,6-dien-24-oic acid increase in HCC, and LPSs decrease. Compression of fatty acids quantitative profiles of HCC by two techniques UPLC-ESI-TQMS and GC-MS revealed that in GC-MS HCC- profile, lignoceric acid (24:0) and nervonic acid (24:1) are absent (44). However, the same technique approach on serum profiles from HCC (n = 82), LC (n = 48), and healthy subjects (n = 90), showed that glycochenodeoxycholic acid is an important indicator of HCC diagnosis and disease prognosis (45).

The finding of comparing urinary metabolic profile of HCC versus the metabolomics profile in early HCC recurrence (one year after operation) introduced that the difference in levels of ethanolamine, lactic acid, acotinic acid, phenylalanine and ribose can introduce for the prediction of early recurrence (46). Ressom, et al. compared sera metabolites of HCC (n=78) and cirrhotic controls (n=184) using ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with a hybrid quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-QTOF MS). Metabolomic investigation of HCC vs. liver cirrhosis showed that levels of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S-1-P) and lysophosphatidylcholine (lyso PC 17:0) that respectively related on sphingolipid metabolism and phospholipid catabolism increased. Decreasing levels of taurocholic acid (TCA), glycocholic acid (GCA), glycochenodeoxycholic acid 3-sulfate (3-sulfo-GCDCA), glycodeoxycholic acid (GDCA), and taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDCA), which are involved in bile acid biosynthesis (specifically cholesterol metabolism) was reported (47). One MS-based metabolic biomarker discovery study was carried on Egyptian subjects by using ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled with quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (UPLC-QTOF MS). Compression of metabolic profile of HCC (n=40) versus cirrhosis (n=49) led to identification of decrease of GCA, GDCA, GCDCA, oleyol carnitine, 3beta, 6betadihydroxy- 5beta-cholan-24- oic acid and up regulation of Phe-Phe (48). In a biochemical study on urine, it has been suggested disruption of primary and secondary steps of bile acid biosynthesis in HCC patients (49). One NMR based study on sera showed the lipoproteins with higher density were up- regulated in cirrhotic patients without HCC (n=93). Glutamate, acetate, and N-acetyl glycoprotein level in large HCC (n=33) significantly increased. Reported metabolomic profiles of small HCC (n=28) patients were similar to large HCC group. Metabolites that correlated with cirrhosis were lipids and glutamine (50).

Urinary metabolites from liver cancer patients and healthy volunteers were studied by metabonomic method based on ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry. Both hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) and reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RPLC) were used to separate the urinary metabolites. Hypoxanthine, Proline betain, Acetyl carnitine, Carnitine and Phenylacetylglutamine were up regulated. However, Carnitine C9:1, and Carnitine C10:3, Butylcarnitine were down regulated (51). Some lipids have been introduced as an agent for progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. In combitional metabolite and gene expression profile study of tumor and non-tumor tissues showed changes in the expression of stearoyl-CoA-desaturase (SCD) associated with HCC. They introduced SCD as a biomarker for aggressive HCC. In aggressive HCC, levels of monounsaturated palmitic acid, the product of SCD activity, were increased and glucose, glycerol 2- and 3-phosphate, malate, alanine and myo-inositol decreased (52). Beyoğlu D, et al. applied GC-MS to present one panel for biomarker discovery in HCC by comparing tumors and non-tumor liver tissues (the members of each group were 31). HCC was characterized by increasing glycolysis, attenuated mitochondrial oxidation, and arachidonic acid synthesis versus decreasing of glucose, malate, alanine, glycerol 3-phosphate, glycerol 2-phosphate , myo-inositol, and linoleic acid (53). 1-methyladenosine has been introduced as a serum characteristic metabolite of HCC patients in one study that have been carried on 41 HCC patients versus 38 healthy controls. In this study, inflammatory stress or oxidative DNA damage due to nucleotides modification and hyperactivation of methyltransferases and subsequently increasing of 1-methyladenosine in HCC samples are reported (40). Compression of metabolite profiles of 16, 14 and 17 samples in the HCC, cirrhosis and healthy controlof Egyptian population showed decreasing in glycine, trimethylamine-N-oxide, hippurate, citrate and creatinin as well as increase in creatine and carnitine in HCC patients (54). Evaluation of male urinary metabolome pattern of HCC (n=20) and healthy control (n=20) by GC/MS showed a different amount of expression in Octanedioic acid, Heptanedioic acid, Ethanedioic acid, Glycine, Xylitol, Phosphate, Propanoic acid, Trihydroxypentanoic acid, Primidine, Threonine, Butanedioic acid, Butanoic acid, Hypoxanthine, Tyrosine, Arabinofuranose, Hydroxy proline dipeptide, and Xylonic acid between two mentioned groups (55). Yang J, et al. collected 50 urine samples of healthy control, 27 liver cirrhosis, 30 acute hepatitis, 20 chronic hepatitis and 48 HCC. Compression of obtained metabolite profiles by HPLC has been shown up-regulation of pseudouridine, 1-methyladenosine, xanthosine, 1methylinosine, 1- and 2-methylguanosine and N4- acetylcytidine, adenosine(56).

NAFLD/NASH

One type of liver disease is Steatohepatitis (also known as fatty liver disease) that is determined by liver inflammation of with simultaneous fat accumulation in liver (57) . The most prevalent chronic liver disease in western countries is NAFLD. Unfortunately, final diagnosis of NAFLD can only be achieved by liver biopsy and histopathological analysis (58). Different studies have been focused on significant favorable methods to find non-invasive markers of liver disease which can distinguish the early stages of damage (59). For this purpose, investigators used new techniques such as metabolomics to discover biomarkers that could be useful in diagnosis of NAFLD in early stage (60-63).A small number of individuals with NAFLD willdevelop to more severe stages of liver disease, including NASH (non-alcoholic steatohepatitis). NASH is usually related to the progression of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (64). NASH leads to accumulation of hepatic fat. Chronic inflammation and reactive oxygen species formation occur as a result of disease progression (65, 66). Unfortunately, liver biopsy is the only way to final verification of the NASH diagnosis and grade of development of disease. While, the early diagnosis of NASH in early stage is virtual to prosperous treatment (66). Lipids are important metabolites that play a significant role in liver diseases. According to the analysis of plasma lipids by mass spectrometry, there was a significant increase in total plasma monounsaturated fatty acids driven by palmitoleic (16:1 n7) and oleic (18:1 n9) acids, as well as gamma-linolenic (18:3n6) and dihomo gamma-linolenic (20:3n6) acids in both NAFLD (n = 25) and NASH (n = 50). Levels of palmitoleic acid, oleic acid and palmitoleic acid to palmitic acid (16:0) ratio were significantly increased in NAFLD. While, in NASH subjects decreasing the docosahexanoic acid (22:6 n3) to docosapentenoic acid (22:5n3) ratio and increasing the level of 11-HETE, a nonenzymatic oxidation product of arachidonic (20:4) acid has been reported (67). Using UPLC-MS, Barr, et al. reported that in NAFLD (n=24) (A parallel animal model /human) level of organic acids, phosphatidylcholine (PC), lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC), Arachidonic acid, Glutamic acid, bile acids (BAs) and sphingomyelin lipids: (SM 36:3), (d18:2/16:0), (d18:2/14:0), (d18:1/18:0), (d18:1/16:0), (d18:1/12:0), and (d18:0/16:0) were changed. The amount of deoxycholic acid was significantly higher in NAFLD versus normal liver (Table 3, 4). Significant changes in serum concentrations of only three phospholipids were reported by compression of NASH serum metabolite with NAFLD (68). In another Metabolomic study by García-Canaveras, et al., 46 samples, 23 from steatotic and 23 from non-steatotic human livers, were analyzed by LC-MS that combines RP and HILIC chromatographic separations. Decreased levels of antioxidant species and higher levels of bile acids and phospholipid degradation products were found in steatotic livers. Also, changes in amino acid metabolism, hypoxanthine, creatinine, glutamate, glutamine, γ-glutamyl-dipeptides concentrations and alterations in energy metabolism were found (69). Plasma Metabolomic analysis by Kalhan SC, et al. showed significant elevation of glycochenodeoxycholate, glycocholate, and taurocholate in NAFLD patients. Concentrations of free carnitine, butyrylcarnitine, and methylbutyrylcarnitine were higher in NASH patients, whereas long-chain fatty acids were lower (details are presented in tables 3 and 4).

Table 3.

Summary of recent metabolomics studies in the field NAFLD

| Reference | Tissue | Platform | Decreased or increased metabolites in the patients compared to the control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puri P (2009) | Plasma | HPTLC GCFID LCMS |

palmitoleic, oleic acids dihomo gamma-linolenic (20:3n6) acids, Triacylglycerols, palmitoleic acid to palmitic acid (16:0) ratio Linoleic acid |

| García-Canaveras JC(2011) | liver | UPLCESIQTOFMS | hypoxanthineglutamine, γ-glutamyl-dipeptides creatinine, GCDCA , TCDCA L-glutamyl-L-lysine, Lleucyl-L-proline, glutamate, |

| Kalhan SC(2011) | plasma | UPLCESITQMS GCMS |

carnitine, butyrylcarnitine (C5), glutamyl dipeptides, glutamyl valine, glutamyl leucine, glutamyl phenylalanine and glutamyl tyrosine, methylbutyrylcarnitine, glycocholate, taurocholate, glycochenodeoxycholate, Mannose and lactate glutathione, long-chain fatty acids and cysteine-glutathione |

| JonathanBarr(2010) | serum | UPLC/MS | lysophosphatidylcholine (LPC),deoxycholic acid bile acids (BAs), sphingomyelin: (SM 36:3), (d18:2/16:0), (d18:2/14:0), (d18:1/18:0), (d18:1/16:0), (d18:1/12:0), and (d18:0/16:0) Creatine |

Red color: increased metabolite

Blue color: decreased metabolite

Table 4.

Summary of recent metabolomic studies in the field NASH

| Subject | Tissue | Platform | Decreased or increased metabolites in the patients compared to the control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Puri P etal(2009) | plasma | HPTLC GCFID LCMS |

11-HETE(5-HETE), 8-HETE and 15-HETE docosahexanoic acid (22:6 n3) to docosapentenoic acid (22:5n3) ratio |

| Kalhan SC(2011) | plasma | UPLCESITQMS GCMS |

aspartate, glutamate, phenylalanine, tyrosine, lactate,isoleucine, leucine, valine, acylcarnitines (C3, C4 and C5), γ-glutamyl-tyrosine glucose, xanthine pyruvate, carnitine, butylcarnitin,free carnitin,methylbutylcarnitin, GCA, TCA, GCDCA,glutamyl dipeptide phenylacetate, indolepropionate, cysteine-glutathione disulfide, glycerate, glycerophosphocholine, LPC(18:1), LPC(18:2), LPC(20:4) |

| Jonathan Barr(2010) | serum | UPLCESIQTOFMS | NASH vs. NAFLD: PC(14:0/20:4), LPC(18:1) NASH vs. NAFLD: LPC(24:0) |

Red color: increased metabolite

Blue color: decreased metabolite

Cysteine-glutathione levels decreased in NASH and steatosis, whereas several glutamyl dipeptides elevated (70).

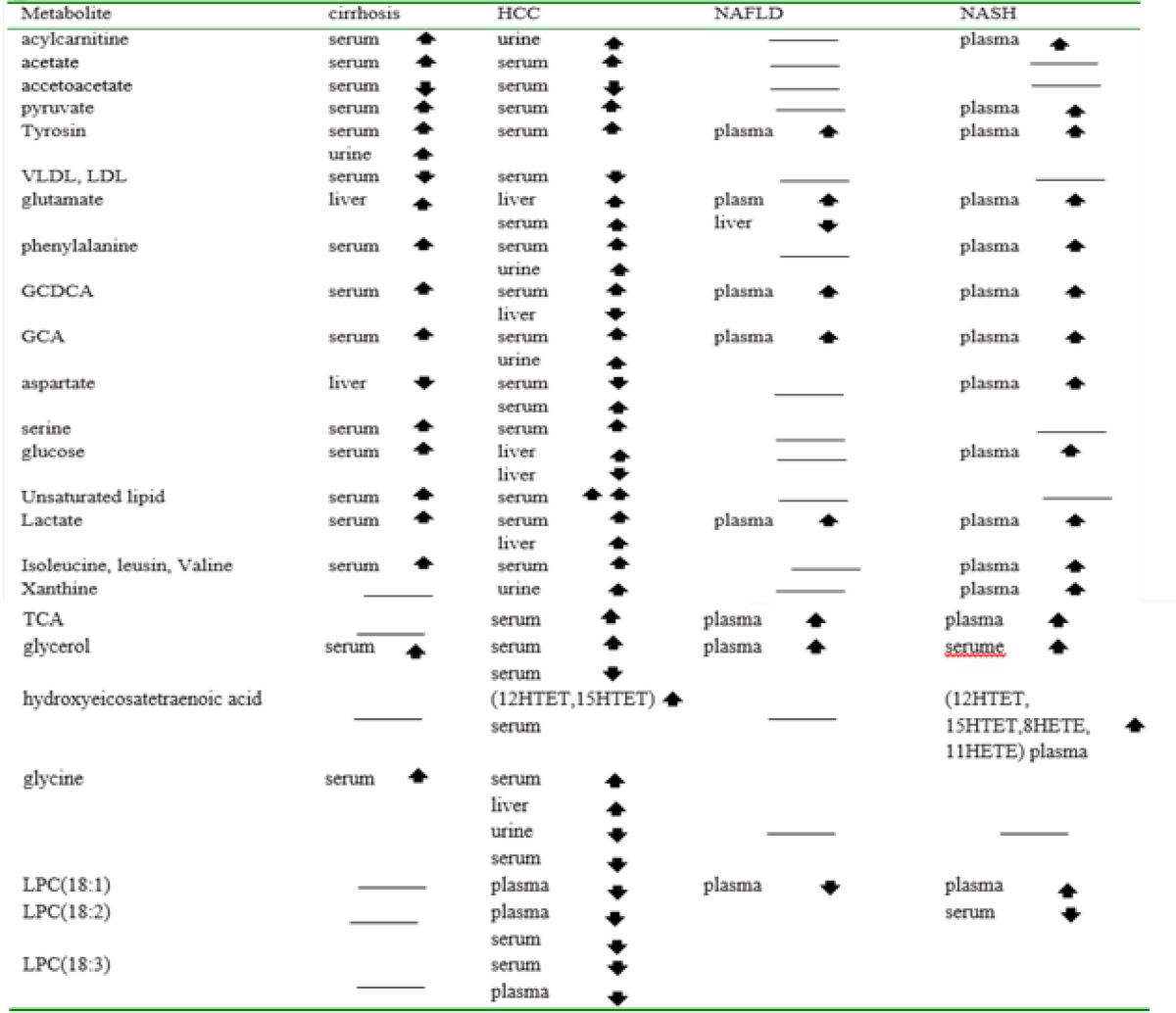

Major metabolites and metabolic pathways in cirrhosis, HCC, NAFLD and NASH

The common metabolites among cirrhosis, HCC, NASFLD, and NASH diseases are shown in table 5. The reported metabolites are: aromatic amino acids (tyrosine, phenylalanine), hydroxyl amino acids (serine), branched-chain amino acids (valine, isoleucine, leucine), basic amino acids (lysine, arginine), acidic amino acids (glutamate, glycine), aliphatic amino acids (alanine, proline), bile acids, (glycocholate (GCA), glycochenodeoxycholate (GCDCA), taurocholate (TCA) and taurochenodeoxycholate (TCDCA), several carboxylic acids (acetate), ketone bodies (acetoacetate), various choline-associated metabolites (choline, trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO)), as well as a number of glycolysis and tricarboxylic acid-cycle (TCA cycle) related metabolites (glucose, pyruvate, lactate, succinate, fumarate, and citrate).

Table 5.

Common metabolites that their levels changed among Cirrhosis, HCC, NAFLD and NASH

The pyruvate concentration elevates in LC and HCC serum. It may be due to reduction of pyruvate utilization into the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (25). The down –regulated acetoacetate in LC and HCC suggest TCA cycle imperfection and energy metabolism deficiency in liver mitochondria (25). Alteration in concentrations of free amino acids in the LC and HCC serum may occur due to destruction protein followed by cell necrosis. Disordered amino acid metabolism was reported in some metabolomic studies (52,53,71). It has been reported that metabolism of essential amino acids and the common branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) such as valine, leucine, and isoleucine change in liver diseases (72). The relation of BCAAs with several types of cancer, including HCC has been reported (73). The up-regulated BCAAs in HCC samples may have tumorigenic effect in the liver (74). They have also been connected to other liver diseases such as cirrhosis (73). The fullness of α-ketoglutarate lead to elevated level of glutamine, which afflux of the mitochondria and converted into glutamine in cytosol (30). In cancer cells, the decreased TCA intermediates led by the synthesis of fatty acids and amino acids can be replenished by glutaminolysis (75). Xanthine is produced from hypoxanthine by xanthine oxidase, and the production of xanthine is accompanied by production of H2O2 (76). The elevated generation of xanthine results in oxidative stress that promotes the development of HCC (26) and NASH (64).

It is reported that serine elevates in hepatocellular carcinoma (26) and cirrhosis(4) serum. The importance of serine in HCC development may be linked to its secondary function as an allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2). PKM2 is the principal cancer isoform of PK that convert phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate during glycolysis (77). Glycine is also a fundamental anabolic metabolite of growing cancers and was shown to be elevated in an HCC metabolomics study (55). Lactate is an intrinsic inflammatory mediator. The promotion of chronic inflammation in tumor microenvironments occurs due to increased interleukin (IL)-17A production by T cells and macrophages that followed by Lactate (78). However, lactate led to a concentration-dependent increasing the migration of various cancer cell lines (79). Glutamate (a key component in cellular metabolism) participates as a mediator in energy pathways (80). It has been shown the deficiency of glutamate signaling can be effective in the initiation and extension of various cancer types. It was suggested that glutamate is active in stimulation of regulatory pathways that control tumor growth, proliferation and survival(81). High level of acylcarnitine in serum has been confirmed in cirrhosis (26), HCC (26) and NASH (64). In cancer cells, increased glycolysis leads to the elevation of pyruvate level in the cytosol. Pyruvate is transferred into the mitochondria to concede acetylCoA as energy substrate. The increase of acetylCoA leads to increased level of acetylcarnitine (51). Also, due to CPTI catalyzes unification of free fatty acid with carnitine, the efficiency in carbamoyl phosphate transferase I (CPTI) may lead to increased level of acylcarnitines. Aberrant acylcarnitine metabolism has been implicated as an important mechanism of cirrhosis onset (82, 83). It was reported that the strongest difference in metabolite groups between HCC and LC belong to lipid metabolism pathways, amino acid metabolism, eicosanoid signaling, acylcarnitine metabolism, nucleotidemetabolism and oxidative stress homoeostasis (26).

The liver can be considered the hub of lipid metabolism. Numerous HCC metabolomics and genomics analyses have been reported aberrations in lipid metabolism as a signature of HCC development (44, 71, 84, 85). The elevated level of 12-Hydroxyicosatetraenoic acid (12-HETE) and 15-HETE (products of lipoxygenase and cytochrome P450 enzymes) impose both pro and anti-inflammatory effects (86). 12-HETE induce the tumor metastatic effect through activation of protein kinase C (87). 15-HETE is a lipid signaling eicosanoid that acts as endothelial cell adhesion, and promote HCC growth and metastasis through the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B/heat shock protein 90 (PI3K/Akt/HSP90) pathway (88). Members of the 5-HETE family, excite target cells by binding and activating a dedicated G protein-coupled receptor (89). G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), has been introduced as key elements in signal transmission, tumor growth, metastasis (90) and increased tumor initiation in liver cell (91).

Oxidative stress through accumulation of ROS species superoxide, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), and hydroxyl radical induce the development of HCC by amplifying DNA damage (92). H2O2, a ROS, is released with the oxidation of every dicarboxylic acid (DCA) and during PPAR-α β-oxidation (DCAs are substrates of PPAR-α β-oxidation). DCA and bile acids have been introduced as metabolites that significantly over-expressed in cirrhosis and increase the oxidative stress and free radicals. Also, accumulating levels of free radicals lead to cell death (32). Therefore, oxidative stress induces the apoptosis and inflammatory reactions, which participates in generation of cirrhosis (93). Changes in LPCs regulation were also reported in HCC (35, 53), NAFLD, and NASH (64). LPC not only convert to lysophosphatidic acid by LysoPLD/ATX(LPA) that is involved in cancer development (94), but also is an important signaling molecule involved in regulating cellular proliferation, cancer cell invasion, and inflammation (95). Inflammatory effects include expression alteration of endothelial cell adhesion molecules, growth factors, chemotaxis, and activation of monocytes / macrophages promoted by LPC (96). It has been shown that bile acids (BA) are very useful for cirrhosis diagnosis and hepatobiliary disease (49, 50, 97-99). Dysfunction of bile acid biosynthesis was also reported to be associated with liver cancer progression and development(35, 100). The BA species, including TCA, and CDCA lead to increased levels of cAMP in a dose-dependent manner that influence glucose metabolism(101). However, expression of the genes participate in lipids, liproproteins or glucose metabolism, controlled by bile acids that are physiological ligands for farnesoid X receptors (FXRs) (102). Bile acids are essential molecules in signaling that induce energy consumption by activating intracellular thyroid hormone and regulating energy homeostasis (103).

Conclusion

Finding biomarkers of liver diseases is one of the most serious goals in the modern medicine. Metabolomics is one of new tools that can apply to earlier disease detection, therapy monitoring and understanding the pathogenesis. In this context, some metabolomics studies were summarized with aim of the identification of metabolites associated with several diseases including cirrhosis, HCC, NAFLD and NASH. In addition, in current review, it has been explained some essential metabolic pathways involved in these diseases, including altered key metabolic pathways such as cellular energy metabolism, bile acids, free fatty acids, glycolysis, and amino acid metabolism, TCA cycle and oxidative stress. There are evidences of deficiency in lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism, TCA cycle and β-oxidation in liver diseases. Thus, metabolic profiling is an essential step towards the early diagnosis and increasing choice of therapy by introducing special biomarkers involved in the initiation and development of liver diseases. More investigation and biomarker validation is required for application of the finding in medicine.

Acknowledgments

This article has been extracted from Akram Safaei PhD thesis.

References

- 1.Schuppan D, Afdhal NH. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2008;371:838–51. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60383-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heidelbaugh JJ, Bruderly M. Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: part I. Diagnosis and evaluation. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:756–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qi SW, Tu ZG, Peng WJ, Wang LX, Ou-Yang X, Cai AJ, et al. 1H NMR-based serum metabolic profiling in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:285–90. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i3.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xue R, Dong L, Wu H, Liu T, Wang J, Shen X. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry screening of serum metabolomic biomarkers in hepatitis B virus infected cirrhosis patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2009;47:305–10. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2009.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gomase VS, Changbhale SS, Patil SA, Kale KV. Metabolomics. Curr Drug Metab. 2008;9:89–98. doi: 10.2174/138920008783331149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zamanian-Azodi M, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Rahmati-Rad S, Hasanzadeh H, Tavirani MR, Seyyedi SS. Protein-Protein Interaction Network could reveal the relationship between the breast and colon cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2015;8:215–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zali H, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Azodi M. Gastric cancer: prevention, risk factors and treatment. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2011;4:175–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamanian-Azodi M, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Hasanzadeh H, RahmatiRad S, Dalilan S, Gilanchi S, et al. Introducing biomarker panel in esophageal, gastric, and colon cancers; a proteomic approach. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2014;1:6–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Safari-Alighiarloo N, Taghizadeh M, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Goliaei B, Peyvandi AA. Protein-Protein Interaction Networks (PPI) and complex diseases. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2014;7:17–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safaei A, Tavirani MR, Oskouei AA, Azodi MZ, Mohebbi SR, Nikzamir AR. Protein-protein interaction network analysis of cirrhosis liver disease. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:114–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rezaei-Tavirani M, Zamanian-Azodi M, Rajabi S, Masoudi-Nejad A, Rostami-Nejad M, Rahmatirad S. Protein clustering and interactome analysis in Parkinson and Alzheimer's diseases. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19:101–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xue R, Lin Z, Deng C, Dong L, Liu T, Wang J, et al. A serum metabolomic investigation on hepatocellular carcinoma patients by chemical derivatization followed by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2008;22:3061–68. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bu Q, Huang Y, Yan G, Cen X, Zhao YL. Metabolomics: a revolution for novel cancer marker identification. Comb Chem High Throughput Screen. 2012;15:266–75. doi: 10.2174/138620712799218563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wojakowska A, Chekan M, Widlak P, Pietrowska M. Application of metabolomics in thyroid cancer research. Inter J Endocrinol. 2015;2015:258763. doi: 10.1155/2015/258763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bro R, Kamstrup-Nielsen MH, Engelsen SB, Savorani F, Rasmussen MA, Hansen L, et al. Forecasting individual breast cancer risk using plasma metabolomics and biocontours. Metabolomics. 2015;11:1376–80. doi: 10.1007/s11306-015-0793-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fathi F, Ektefa F, Oskouie AA, Rostami K, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Alizadeh AHM, et al. NMR based metabonomics study on celiac disease in the blood serum. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6:190–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fathi F, Kasmaee LM, Sohrabzadeh K, Rostami-Nejad M, Tafazzoli M, Oskouie AA. The differential diagnosis of Crohn’s disease and celiac disease using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Appl Magn Reson. 2014;45:451–59. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fathi F, Majari‐Kasmaee L, Mani‐Varnosfaderani A, Kyani A, Rostami‐Nejad M, Sohrabzadeh K, et al. 1H NMR based metabolic profiling in Crohn's disease by random forest methodology. Magn Reson Chem. 2014;52:370–76. doi: 10.1002/mrc.4074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fathi F, Oskouie AA, Tafazzoli M, Naderi N, Sohrabzedeh K, Fathi S, et al. Metabonomics based NMR in Crohn's disease applying PLS-DA. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2013;6:S82–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nobakht MGBF, Aliannejad R, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Taheri S, Oskouie AA. The metabolomics of airway diseases, including COPD, asthma and cystic fibrosis. Biomarkers. 2015;20:5–16. doi: 10.3109/1354750X.2014.983167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arakaki AK, Skolnick J, McDonald JF. Marker metabolites can be therapeutic targets as well. Nature. 2008;456:443. doi: 10.1038/456443c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Zhang A, Han Y, Wang P, Sun H, Song G, et al. Urine metabolomics analysis for biomarker discovery and detection of jaundice syndrome in patients with liver disease. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:370–80. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.016006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Claudino WM, Quattrone A, Biganzoli L, Pestrin M, Bertini I, Di Leo A. Metabolomics: available results, current research projects in breast cancer, and future applications. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2840–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.7550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang A, Sun H, Yan G, Wang P, Wang X. Mass spectrometry‐based metabolomics: applications to biomarker and metabolic pathway research. Biomed Chromatogr. 2016;30:7–12. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khamis MM, Adamko DJ, El‐Aneed A. Mass spectrometric based approaches in urine metabolomics and biomarker discovery. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2015;16:21455. doi: 10.1002/mas.21455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dunn WB, Ellis DI. Metabolomics: current analytical platforms and methodologies. Trend Anal Chem. 2005;24:285–94. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alonso A, Marsal S, Julià A. Analytical methods in untargeted metabolomics: state of the art in 2015. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2015;3:23. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2015.00023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mokdad AA, Lopez AD, Shahraz S, Lozano R, Mokdad AH, Stanaway J, et al. Liver cirrhosis mortality in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 2014;18:145–69. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0145-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim MY, Baik SK. Hyperdynamic circulation in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009;54:143–48. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2009.54.3.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao H, Lu Q, Liu X, Cong H, Zhao L, Wang H, et al. Application of 1H NMR‐based metabonomics in the study of metabolic profiling of human hepatocellular carcinoma and liver cirrhosis. Can Sci. 2009;100:782–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xue R, Dong L, Wu H, Liu T, Wang J, Shen X. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry screening of serum metabolomic biomarkers in hepatitis B virus infected cirrhosis patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2009;47:305–10. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2009.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fitian AI, Nelson DR, Liu C, Xu Y, Ararat M, Cabrera R. Integrated metabolomic profiling of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C cirrhosis through GC/MS and UPLC/MS‐MS. Liver Int. 2014;34:1428–44. doi: 10.1111/liv.12541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang T, Zheng X, Xing F, Zhuo H, Liu C. Serum metabolomic characteristics of patients with liver cirrhotic ascites. Integr Med Int. 2014;1:136–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin X, Zhang Y, Ye G, Li X, Yin P, Ruan Q, et al. Classification and differential metabolite discovery of liver diseases based on plasma metabolic profiling and support vector machines. J Sep Sci. 2011;34:3029–36. doi: 10.1002/jssc.201100408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yin P, Wan D, Zhao C, Chen J, Zhao X, Wang W, et al. A metabonomic study of hepatitis B-induced liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by using RP-LC and HILIC coupled with mass spectrometry. Mol Biosyst. 2009;5:868–76. doi: 10.1039/b820224a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shao Y, Zhu B, Zheng R, Zhao X, Yin P, Lu X, et al. Development of urinary pseudo-targeted LC-MS based metabolomics method and its application in hepatocellular carcinoma biomarker discovery. J Proteome Res. 2015;14:906–16. doi: 10.1021/pr500973d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dai W, Yin P, Chen P, Kong H, Luo P, Xu Z, et al. Study of urinary steroid hormone disorders: difference between hepatocellular carcinoma in early stage and cirrhosis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2014;406:4325–35. doi: 10.1007/s00216-014-7843-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez-Granados B, Morales JM, Rodrigo JM, Del Olmo J, Serra MA, Ferrández A, et al. Metabolic profile of chronic liver disease by NMR spectroscopy of human biopsies. Int J Mol Med. 2011;27:111–17. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2010.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Serag HB, Rudolph KL. Hepatocellular carcinoma: epidemiology and molecular carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2557–76. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen F, Xue J, Zhou L, Wu S, Chen Z. Identification of serum biomarkers of hepatocarcinoma through liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry-based metabonomic method. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2011;401:1899–904. doi: 10.1007/s00216-011-5245-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan Y, Yin P, Tang L, Xing W, Huang Q, Cao D, et al. Metabolomics study of stepwise hepatocarcinogenesis from the model rats to patients: potential biomarkers effective for small hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:14–9. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.010694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Y, Li C, Nie X, Feng X, Chen W, Yue Y, et al. Metabonomic studies of human hepatocellular carcinoma using high-resolution magic-angle spinning 1H NMR spectroscopy in conjunction with multivariate data analysis. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:2605–14. doi: 10.1021/pr070063h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen T, Xie G, Wang X, Fan J, Qiu Y, Zheng X, et al. Serum and urine metabolite profiling reveals potential biomarkers of human hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10:25–31. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.004945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Patterson AD, Maurhofer O, Beyoğlu D, Lanz C, Krausz KW, Pabst T, et al. Aberrant lipid metabolism in hepatocellular carcinoma revealed by plasma metabolomics and lipid profiling. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6590–600. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang B, Chen D, Chen Y, Hu Z, Cao M, Xie Q, et al. Metabonomic profiles discriminate hepatocellular carcinoma from liver cirrhosis by ultraperformance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:1217–27. doi: 10.1021/pr2009252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ye G, Zhu B, Yao Z, Yin P, Lu X, Kong H, et al. Analysis of urinary metabolic signatures of early hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence after surgical removal using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:4361–72. doi: 10.1021/pr300502v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ressom HW, Xiao JF, Tuli L, Varghese RS, Zhou B, Tsai TH, et al. Utilization of metabolomics to identify serum biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. Anal Chim Acta. 2012;743:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xiao JF, Varghese RS, Zhou B, Nezami Ranjbar MR, Zhao Y, Tsai TH, et al. LC-MS based serum metabolomics for identification of hepatocellular carcinoma biomarkers in Egyptian cohort. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5914–23. doi: 10.1021/pr300673x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang A, Sun H, Yan G, Han Y, Ye Y, Wang X. Urinary metabolic profiling identifies a key role for glycocholic acid in human liver cancer by ultra-performance liquid-chromatography coupled with high-definition mass spectrometry. Clin Chim Acta. 2013;418:86–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nahon P, Amathieu R, Triba MN, Bouchemal N, Nault J-C, Ziol M, et al. Identification of serum proton NMR metabolomic fingerprints associated with hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Clin Can Res. 2012;18:6714–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen J, Wang W, Lv S, Yin P, Zhao X, Lu X, et al. Metabonomics study of liver cancer based on ultra performance liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry with HILIC and RPLC separations. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;650:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Budhu A, Roessler S, Zhao X, Yu Z, Forgues M, Ji J, et al. Integrated metabolite and gene expression profiles identify lipid biomarkers associated with progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and patient outcomes. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1066–75. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.01.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Beyoğlu D, Imbeaud S, Maurhofer O, Bioulac‐Sage P, Zucman‐Rossi J, Dufour JF, et al. Tissue metabolomics of hepatocellular carcinoma: tumor energy metabolism and the role of transcriptomic classification. Hepatology. 2013;58:229–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.26350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shariff MI, Gomaa AI, Cox IJ, Patel M, Williams HR, Crossey MM, et al. Urinary metabolic biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma in an Egyptian population: a validation study. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:1828–36. doi: 10.1021/pr101096f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu H, Xue R, Dong L, Liu T, Deng C, Zeng H, et al. Metabolomic profiling of human urine in hepatocellular carcinoma patients using gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2009;648:98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yang J, Xu G, Zheng Y, Kong H, Pang T, Lv S, et al. Diagnosis of liver cancer using HPLC-based metabonomics avoiding false-positive result from hepatitis and hepatocirrhosis diseases. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2004;813:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vuppalanchi R, Chalasani N. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Selected practical issues in their evaluation and management. Hepatology. 2009;49:306–17. doi: 10.1002/hep.22603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poynard T, Ratziu V, Naveau S, Thabut D, Charlotte F, Messous D, et al. The diagnostic value of biomarkers (Steatotest) for the prediction of liver steatosis. Comp Hepatol. 2005;4:10–24. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-4-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guha I, Parkes J, Roderick P, Harris S, Rosenberg W. Non-invasive markers associated with liver fibrosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut. 2006;55:1650–60. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.091454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Preiss D, Sattar N. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an overview of prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment considerations. Clin Sci. 2008;115:141–50. doi: 10.1042/CS20070402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1221–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Adams LA, Angulo P, Lindor KD. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. CMAJ. 2005;172:899–905. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.045232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Adams LA, Lindor KD. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17:863–69. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kneeman JM, Misdraji J, Corey KE. Secondary causes of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2012;5:199–207. doi: 10.1177/1756283X11430859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sakaguchi S, Takahashi S, Sasaki T, Kumagai T, Nagata K. Progression of alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: common metabolic aspects of innate immune system and oxidative stress. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2010;26:30–46. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-10-rv-087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang W, Lindeman JH, Menke AL, Koonen DP, Morrison M, Havekes LM, et al. Metabolically induced liver inflammation leads to NASH and differs from LPS-or IL-1β-induced chronic inflammation. Lab Invest. 2014;94:491–502. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2014.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Puri P, Wiest MM, Cheung O, Mirshahi F, Sargeant C, Min HK, et al. The plasma lipidomic signature of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2009;50:1827–38. doi: 10.1002/hep.23229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barr J, Vázquez-Chantada M, Alonso C, Pérez-Cormenzana M, Mayo R, Galán A, et al. Liquid chromatography− mass spectrometry-based parallel metabolic profiling of human and mouse model serum reveals putative biomarkers associated with the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. J Proteome Res. 2010;9:4501–12. doi: 10.1021/pr1002593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.García-Canaveras JC, Donato MT, Castell JV, Lahoz A. A comprehensive untargeted metabonomic analysis of human steatotic liver tissue by RP and HILIC chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry reveals important metabolic alterations. J Proteome Res. 2011;10:4825–34. doi: 10.1021/pr200629p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kalhan SC, Guo L, Edmison J, Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Hanson RW, et al. Plasma metabolomic profile in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2011;60:404–13. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li S, Liu H, Jin Y, Lin S, Cai Z, Jiang Y. Metabolomics study of alcohol-induced liver injury and hepatocellular carcinoma xenografts in mice. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2011;879:2369–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Landel AM, Hammond WG, Meguid MM. Aspects of amino acid and protein metabolism in cancer‐bearing states. Cancer. 1985;55:230–37. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19850101)55:1+<230::aid-cncr2820551305>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Connell TM. The complex role of branched chain amino acids in diabetes and cancer. Metabolites. 2013;3:931–45. doi: 10.3390/metabo3040931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nezami RM, Luo Y, Di Poto C, Varghese R, Ferrarini A, Zhang C, et al. GC-MS based plasma metabolomics for identification of candidate biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma in Egyptian Cohort. PLoS One. 2014;10:e0127299. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhou S, Huang C, Wei Y. The metabolic switch and its regulation in cancer cells. Sci China Life Sci. 2010;53:942–58. doi: 10.1007/s11427-010-4041-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stirpe F, Ravaioli M, Battelli MG, Musiani S, Grazi GL. Xanthine oxidoreductase activity in human liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2079–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaneton B, Hillmann P, Zheng L, Martin AC, Maddocks OD, Chokkathukalam A, et al. Serine is a natural ligand and allosteric activator of pyruvate kinase M2. Nature. 2012;491:458–62. doi: 10.1038/nature11540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yabu M, Shime H, Hara H, Saito T, Matsumoto M, Seya T, et al. IL-23-dependent and -independent enhancement pathways of IL-17A production by lactic acid. Int Immunol. 2011;23:29–41. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Goetze K, Walenta S, Ksiazkiewicz M, Kunz-Schughart LA, Mueller-Klieser W. Lactate enhances motility of tumor cells and inhibits monocyte migration and cytokine release. Int J Oncol. 2011;39:453–63. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bradbury MJ, Campbell U, Giracello D, Chapman D, King C, Tehrani L. Metabotropic glutamate receptor mGlu5 is a mediator of appetite and energy balance in rats and mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;313:395–402. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.076406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Prickett TD, Samuels Y. Molecular pathways: dysregulated glutamatergic signaling pathways in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4240–46. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amodio P, Angeli P, Merkel C, Menon F, Gatta A. Plasma carnitine levels in liver cirrhosis: relationship with nutritional status and liver damage. Clin Chem Lab Med. 1990;28:619–26. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1990.28.9.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.de la Peña CA, Rozas I, Alvarez-Prechous A, Pardinas M, Paz J, Rodriguez-Segade S. Free carnitine and acylcarnitine levels in sera of alcoholics. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1990;44:77–83. doi: 10.1016/0885-4505(90)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cao H, Huang H, Xu W, Chen D, Yu J, Li J, et al. Fecal metabolome profiling of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma patients by ultra performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry. Anal Chim Acta. 2011;691:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wu JM, Skill NJ, Maluccio MA. Evidence of aberrant lipid metabolism in hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB. 2010;12:625–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00207.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Uderhardt S, Krönke G. 12/15-Lipoxygenase during the regulation of inflammation, immunity, and self-tolerance. J Mol Med. 2012;90:1247–56. doi: 10.1007/s00109-012-0954-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu B, Timar J, Howlett J, Diglio C, Honn K. Lipoxygenase metabolites of arachidonic and linoleic acids modulate the adhesion of tumor cells to endothelium via regulation of protein kinase C. Cell Regul. 1991;2:1045–55. doi: 10.1091/mbc.2.12.1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ma J, Zhang L, Zhang J, Liu M, Wei L, Shen T, et al. 15-Lipoxygenase-1/15-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid promotes hepatocellular cancer cells growth through protein kinase B and heat shock protein 90 complex activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:1031–41. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hosoi T, Koguchi Y, Sugikawa E, Chikada A, Ogawa K, Tsuda N, et al. Identification of a novel human eicosanoid receptor coupled to Gi/o. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31459–65. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:79–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yan M, Li H, Zhu M, Zhao F, Zhang L, Chen T, et al. G protein-coupled receptor 87 (GPR87) promotes the growth and metastasis of CD133+ cancer stem-like cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Marra M, Sordelli IM, Lombardi A, Lamberti M, Tarantino L, Giudice A, et al. Molecular targets and oxidative stress biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma: an overview. J Transl Med. 2011;9:1479–5876. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-9-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Constantinou MA, Theocharis SE, Mikros E. Application of metabonomics on an experimental model of fibrosis and cirrhosis induced by thioacetamide in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharm. 2007;218:11–9. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barber MN, Risis S, Yang C, Meikle PJ, Staples M, Febbraio MA, et al. Plasma lysophosphatidylcholine levels are reduced in obesity and type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e41456. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Goetzl EJ. Pleiotypic mechanisms of cellular responses to biologically active lysophospholipids. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2001;64:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0090-6980(01)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kita T, Kume N, Ishii K, Horiuchi H, Arai H, Yokode M. Oxidized LDL and expression of monocyte adhesion molecules. Diabetes Res Clin. 1999;45:123–26. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(99)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Barnes S, Gallo GA, Trash DB, Morris JS. Diagnositic value of serum bile acid estimations in liver disease. J Clin Pathol. 1975;28:506–9. doi: 10.1136/jcp.28.6.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Neale G, Lewis B, Weaver V, Panveliwalla D. Serum bile acids in liver disease. Gut. 1971;12:145–52. doi: 10.1136/gut.12.2.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Festi D, Labate AMM, Roda A, Bazzoli F, Frabboni R, Rucci P, et al. Diagnostic effectiveness of serum bile acids in liver diseases as evaluated by multivariate statistical methods. Hepatology. 1983;3:707–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840030514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gowda GN. Human bile as a rich source of biomarkers for hepatopancreatobiliary cancers. Biomarkers Med. 2010;4:299–314. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maruyama T, Miyamoto Y, Nakamura T, Tamai Y, Okada H, Sugiyama E, et al. Identification of membrane-type receptor for bile acids (M-BAR) Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;298:714–19. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02550-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Thomas C, Pellicciari R, Pruzanski M, Auwerx J, Schoonjans K. Targeting bile-acid signaling for metabolic diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:678–93. doi: 10.1038/nrd2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Watanabe M, Houten SM, Mataki C, Christoffolete MA, Kim BW, Sato H, et al. Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature. 2006;439:484–89. doi: 10.1038/nature04330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]