Abstract

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy is one of the most sensitive spectroscopic techniques available, with single-molecule detection possible on a range of noble-metal substrates. It is widely used to detect molecules that have a strong Raman response at very low concentrations. Here we present photo-induced-enhanced Raman spectroscopy, where the combination of plasmonic nanoparticles with a photo-activated substrate gives rise to large signal enhancement (an order of magnitude) for a wide range of small molecules, even those with a typically low Raman cross-section. We show that the induced chemical enhancement is due to increased electron density at the noble-metal nanoparticles, and demonstrate the universality of this system with explosives, biomolecules and organic dyes, at trace levels. Our substrates are also easy to fabricate, self-cleaning and reusable.

Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy is a sensitive technique capable of detecting single molecules via their vibrational fingerprints. Here, the authors demonstrate improved sensitivity with photo-induced enhanced Raman spectroscopy applied to trace-level detection of explosives and other analytes.

Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy is a sensitive technique capable of detecting single molecules via their vibrational fingerprints. Here, the authors demonstrate improved sensitivity with photo-induced enhanced Raman spectroscopy applied to trace-level detection of explosives and other analytes.

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is one of the most popular and powerful techniques in analytical chemistry, with single-molecule detection potentially accessible with noble-metal structures or substrates1,2,3,4,5. The adsorption of analyte molecules to a roughened metal surface (typically a gold or silver nanoparticle) leads to strong enhancement of the analyte's Raman signals. The low limits of detection enable trace analysis of highly important molecules such as explosives, pesticides and biomarkers for the protection and preservation of human health6,7,8.

The two key contributions to the SERS enhancement are the electromagnetic (EM) factor and the chemical contribution9. The EM enhancement of SERS-active substrates is by far the most important, and it is mainly determined by the nanostructure of the metallic surface and the wavelength-dependent dielectric properties of the metal. The conduction electrons of these nanoscale features can be driven by the incident electric field in collective oscillations known as localized surface plasmon resonances (LSPRs). These plasmonic materials are able to localize the electromagnetic field at sub-wavelength scales, thus effectively acting as nano-antennas10,11,12,13. However, the difficulty in arranging nanoparticles on a substrate to create the ideal SERS hotspots, means that the possible sensitivities are often not obtained in an easy or repeatable fashion14. On the other hand, the chemical contribution has been associated with smaller additional enhancements and its microscopic origin and overall contribution to the SERS enhancement are still under debate. Several models have been put forward depending on the specific system under study, including the adatom15, the metal-molecule charge transfer resonance9,16,17 and the polarizability modulation models18,19. These models were proposed to explain enhancements in different systems, but there are few demonstrations on how to induce and generalize this mechanism/effect.

SERS on (non photo-activated) semiconductor materials has been explored20,21,22. It has been shown that the main enhancement mechanism is non-plasmon based23,24, with enhancement factors, until recently, lower than those reported for metallic substrates25. The incorporation of metallic particles onto these (non-active) substrates leads to hot-electron migration from the particles to the semiconductor under visible light illumination26, with no effect on the SERS signal beyond that arising from the metallic particles alone27. There has also been limited work on the incorporation of semiconductor nanoparticles on roughened gold SERS substrates for enhancement28.

Meanwhile, catalytic applications for ultraviolet light photo-activated TiO2 have been extensively explored29, including the incorporation of metallic nanoparticles30. Core–shell charge transfer between Ag cores with a TiO2 shell has been demonstrated by Kamat et al. with ultraviolet irradiation31. However, covering the metallic core limits the applications for binding analytes directly to the silver particles. This has detrimental consequences for the SERS enhancement factors. For plasmonic applications—such as SERS—the molecules must be as close as possible to the metal surface as EM enhancement decays exponentially with the distance (d) from surface2. The chemical contribution implies charge transfer between the substrate and the molecule, thus also depends on d.

We propose here photo-induced SERS enhancement, whereby pre-irradiation (photo-excitation) of a semiconductor, such as TiO2 enables strong Raman enhancement at the nanoparticle sites, increasing sensitivity beyond the normal SERS effect. We call this effect photo induced enhanced Raman spectroscopy—PIERS. In our system the molecules can be directly adsorbed to the metallic particle, allowing controlled enhancement by both the EM factor and chemical enhancement factor. As there is no requirement for simultaneous ultraviolet irradiation, which may cause analyte degradation, and our system is applicable to a wide range of engineered gold SERS substrates, thus the PIERS effect may become a useful method of enhancing Raman spectra.

Results

Substrate synthesis

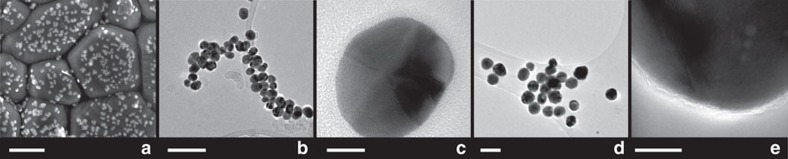

To create our PIERS substrates, citrate-capped gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) (27 nm, s.d. of 5 nm, LSPR of 520 nm in water) or silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) (58 nm, s.d. of 14 nm, LSPR of 428 nm in water) were deposited from MeOH/H2O on a TiO2 rutile (R) surface formed by atmospheric pressure chemical vapour deposition (APCVD). The thickness of the TiO2 was ca. 500 nm, and the final particle concentration was ca. 250 particles per μm2 (Fig. 1). This substrate was then irradiated with ultraviolet light (254 nm—UVC) for a period of time, followed by deposition of the analyte sample and Raman analysis using a 633 nm excitation laser (1.9 mW). We chose both Au and Ag particles for our analysis, to disentangle electromagnetic and chemical enhancement effects, as on TiO2 only the Au LSPR resonance will be in better resonance with the 633 excitation laser line. A schematic is presented in Fig. 2. In the first instance Rhodamine 6G (R6G) was used as a standard (and commonly applied) analyte and significant enhancements over spectral intensities on non-irradiated substrates (those demonstrating normal SERS) were seen (Fig. 3a). Physical characterization of the TiO2 substrate was performed before and after irradiation, and no change in composition was observed by X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Fig. 1). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy confirmed the presence of the gold particles. (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Electron microscopy of substrate and particles.

(a) AuNPs on TiO2 (b,c) AuNPs, (d,e) AgNPs. Scale bars given are 500 nm (a), 100 nm (b,d) and 10 nm (c,e).

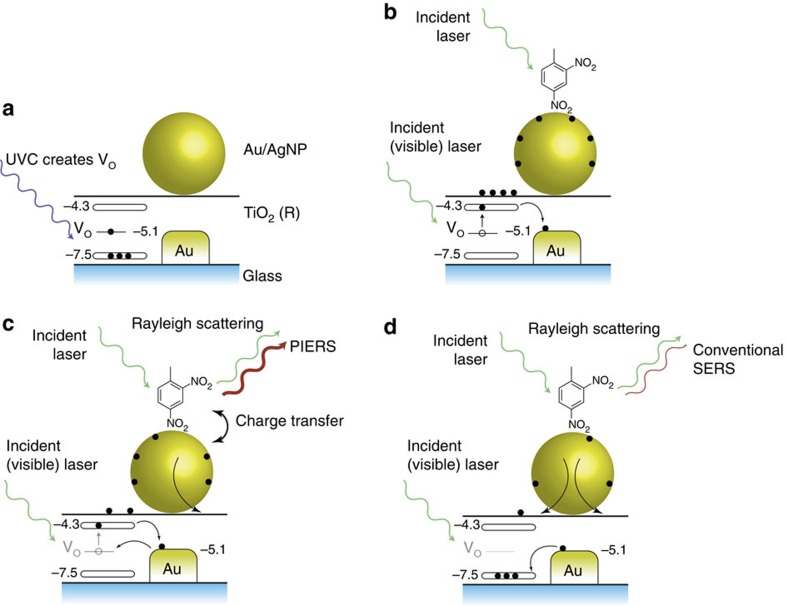

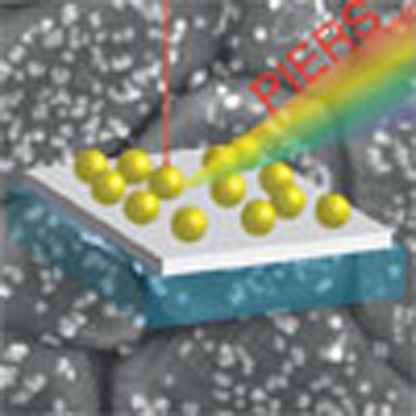

Figure 2. Photo-induced enhanced Raman spectroscopy (PIERS).

(a) Ultraviolet C light (UVC) pre-irradiation creates oxygen vaccencies (VO) in the TiO2 below the conduction band. (b) The sample (here dinitrotoluene) is deposited and irradiation with the Raman laser (633 nm) photoexcites the TiO2, leading to increase in charge on the nanoparicles. (c) The charged nanoparticless lead to the PIERS enhancement. As the VO are replenished, upon exposure to air, fewer electrons can be photoexcited into the conduction band of TiO2. (d) The PIERS effect gradually disappears as the VO are completely replenished over time (30–60 min). The substrate can then be cleaned and recharged through exposure to more UVC light.

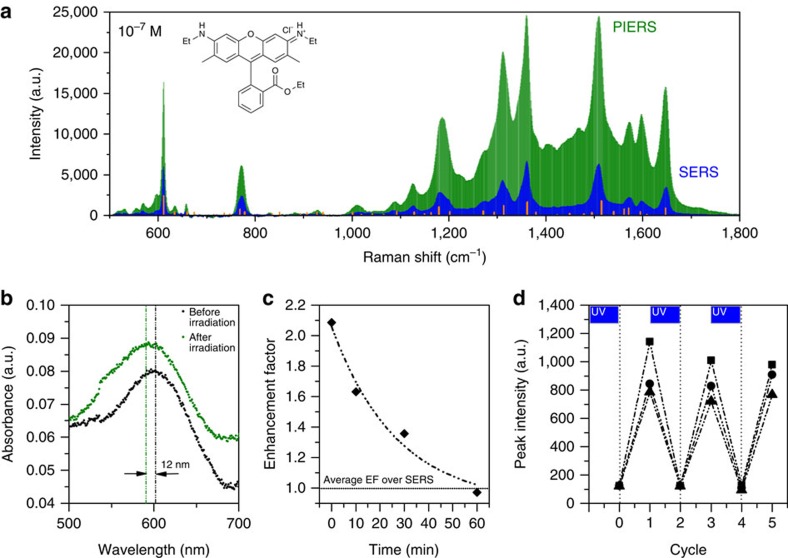

Figure 3. PIERS spectra and examining the PIERS mechanism.

(a) PIERS (green) and SERS (blue) spectra of Rhodamine 6G (10−7 M), with Raman modes of the solid shown by the orange lines. All spectra collected under identical collection conditions. (b) Absorption spectra of a thin film showing LSPR shifts for AuNPs on TiO2 (R) after irradiation with 254 nm light (3 h). Note that the AuNP pre-irradiation LSPR is red-shifted from its solution value, due to the high-refractive index of the TiO2 surface compared with water. Dashed lines indicate peak position (c) Average of total spectral enhancement (EF) of PIERS over SERS for dinitrotoluene (10−9 M) over time (full spectra in Supplementary Fig. 3). Horizontal line indicates the normal SERS intensity. (d) Demonstrating the recyclability of the substrate on irradiation to clean and re-charge for measuring DNT (10–9 M) at three wavelengths, 1,315 cm−1 (squares), 1,367 cm−1 (circles) and 1,385 cm−1 (triangles) (full spectra in Supplementary Fig. 4). Sample irradiation cycles with 254 nm light are marked with blue boxes, then spectra are taken before (on the vertical lines) and after adding DNT, before re-irradiating.

PIERS effect and mechanism

The mechanism of action for PIERS is proposed to be ultraviolet light mediating electron migration from the semiconductor substrate, TiO2 (R), to the metallic nanoparticle (Fig. 2): the PIERS effect is based on carrier migration and separation from the active TiO2 (R) surface to the AuNPs. It has been demonstrated that pre-irradiation with UVC wavelengths can create oxygen vacancy (VO) defects on TiO2 surfaces32. These VO species produce donor states at ∼0.7 eV below the TiO2 conduction band edge33 and induce optical absorption above 500 nm (ref. 34). In the PIERS effect, electrons will thus be promoted from the VO states into the conduction band of TiO2 upon Raman laser illumination and then transferred into Au energy levels35. The process will slowly decay, with a lifetime of approximately an hour, due to surface healing upon exposure of the substrate to air36. Indeed, our results show an intensity decrease of the PIERS signal occurring within the initial 30–60 min (Fig. 3c). This long lifetime of the excited carriers on the Au nanoparticles allows us to evaluate their influence on SERS/PIERS after substrate activation with UVC pre-irradiation.

To demonstrate the activation of the AuNPs we measured the absorption spectra of the substrates before and after UVC irradiation. As shown in Fig. 3b, a 12 nm blue-shift of the AuNP LSPR is observed on irradiation, due to the increasing electron density on the particles31. In conjunction to this, the full width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the LSPR increases from 72 to 88 nm on irradiation. This is in agreement with the work of Brown et al.37 who, in bias-dependent experiments of Au nanoparticles deposited on indium-tin oxide substrates, also observed a blue-shift, increased intensity and broadening of the FWHM of the LSPR peak when a negative potential is applied, confirming our idea of a light-induced charge transfer process from TiO2 to the AuNPs. Following the approach of Mulvaney et al.38 we can estimate the injected electron density (ΔN/N) on the AuNPs due to TiO2 pre-irradiation as follows:

|

Where Δλ is the measured wavelength shift (∼−12 nm) and λ0 is the initial AuNP plasmon peak position on the TiO2 substrate (∼605 nm). From Fig. 3b we can extract then (ΔN/N)≈4% (this data was taken 20 min after pre-irradiation ended).

To further demonstrate the effect, the reduction of PIERS intensity after standing the substrate in the dark was monitored over an hour, in comparison to a non-irradiated SERS film, to show how recombination of the TiO2 excitons reduced the enhancement (Fig. 3c). From Fig. 3b and c, we can estimate the initial injected charge density (at time 0) is about 10%. Finally, a similar substrate was prepared using a more photo-inactive SiO2 film with similar AuNP and analyte loadings, and no significant PIERS enhancement was observed after the ultraviolet pre-treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5); nor was any enhancement observed in the absence of metallic nanoparticles (Supplementary Fig. 6).

The experiments presented so far demonstrate that there is a net charge transfer process to the AuNPs resulting from the activation of the TiO2 substrate via pre-irradiation. We have quantified the density of transferred charge and also showed the lifetime decay by following the PIERS signal. The fact that similar PIERS enhancements are seen with AgNPs (LSPR on TiO2 at 460 nm) demonstrates that the observed enhancement in signal upon ultraviolet treatment is indeed chemical in nature, in addition to a contribution from electromagnetic field enhancement effects (Supplementary Figs 7 and 8).

The (average) order of magnitude enhancement found for PIERS respect to SERS and the inhomogeneous enhancements between different peaks in the Raman spectra when comparing both, points towards an improved chemical enhancement in PIERS, beyond the typical EM effect39. Indeed, in both AuNP and AgNP cases, the injected charges will shift the Fermi level of the nanoparticle to more negative potentials. The exact value of the new Fermi level is dependent on the size of the nanoparticle40, and as a consequence we expect a broad distribution of Fermi level values depending on both the intrinsic size of the nanoparticle and the amount of charge injected. This fact is also reflected in the spectral broadening of the post-irradiated sample in Fig. 3b. Having isolated particles on the substrate avoids equilibration of the charges (Fig. 1), resulting in different individual contributions to the observed chemical enhancement in the PIERS signal, depending on each particular Fermi level shift.

To account for the influence of a broad and new AuNP Fermi level distribution in the PIERS signal (compared to the SERS signal), it is necessary to analyse the parameters involved in the molecule-to-substrate (or vice-versa) charge transfer process, (the origin of the chemical enhancement)16. In this way, the differential Raman cross-section in SERS can account for the microscopic contributions to the chemical enhancement mechanism. By computing this parameter, Tognalli et al.9 clearly show how depositing a single Ag layer over an active Au SERS substrate results in the appearance of a new molecule Fermi level charge transfer resonance, thus enhancing the Raman signal of 4-mercaptopyridine molecules. In our case, the injected charges also shift the Fermi level of the AuNP over a broad distribution of more negative values. As a consequence, this will broaden the resonance conditions between the Fermi level and the molecular orbitals, increasing the charge transfer transitions probabilities over a wider variety of molecules deposited on the substrates.

Detecting explosives and biomolecules

The possibility of photo-inducing chemical enhancement of SERS, independently of the nature of the molecule, even for low Raman cross-section species, leads to a wide range of applications for this PIERS technique. An area where SERS substrates are of great value is in homeland security, for detection of high explosives during environmental monitoring and post-blast forensics41. This requires SERS techniques that work on inexpensive, reusable substrates with high sensitivities for low-cross-section molecules such as nitro-aliphatic PETN (pentaerythritol tetranitrate) and RDX (cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine), as well as the widely used TNT (trinitrotoluene) and its decomposition product DNT (dinitrotoluene). Other areas of interest are small biomolecule sensing, for example in glucose monitoring, or pollution monitoring and control, with similar substrate requirements.

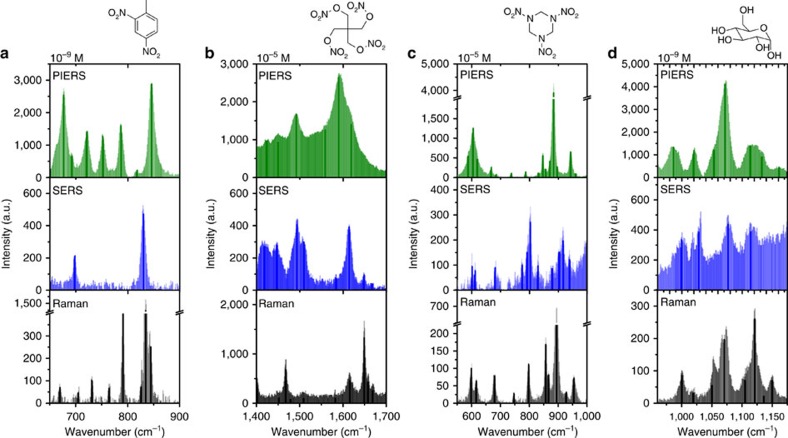

Initial experiments on R6G and DNT showed that the enhancement factor varied between the different bands, with some bands showing an enhancement factor of 20 × over conventional SERS, and some bands were visible only in the PIERS spectra (Fig. 4; Supplementary Table 1; Supplementary Note 1). This kind of selective mode enhancement, along with small shifts in peak position, is typical of chemical enhancement15,18. Due to this PIERS enhancement, it was possible to get an excellent Raman spectrum of DNT at concentrations as low as 10−15 M (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Figure 4. Comparative PIERS spectra of explosives and biomolecules.

Raman of pure solid (black), SERS (blue) and PIERS (green) of molecules of interest on a gold nanoparticle/TiO2 substrate. Darker lines indicate the positions of spectral maxima to aid comparison. SERS and PIERS samples deposited from identical volume of solution: (a) 10−9 M dinitrotoluene (DNT), (b) 10−5 M pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN), (c) 10−5 M cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine (RDX), (d) 10−9 M glucose. Raman spectra collected from pure reference powders/liquids. Each spectrum was collected with the same conditions, giving the increase in intensity for the PIERS spectra, and full collection details are given in the Methods, along with full spectra in Supplementary Fig. 10.

To demonstrate the versatility of the PIERS beyond DNT and R6G, other materials of interest with low Raman cross-sections, such as pentaerythritol tetranitrate (PETN), RDX (cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine) (explosives) and glucose (biomarker) were tested (Fig. 4; Supplementary Fig. 10). There was significant enhancement over their solid and SERS spectra, demonstrating the power of the PIERS technique to enhance spectra of many classes of explosive molecules, not just high cross-section organic dyes or nitroaromatics.

Vapour phase detection of high explosives was attempted with a solid sample of TNT, placed 5 cm from the pre-irradiated substrate and the system was allowed to equilibrate for 5 min. The PIERS spectrum was then measured (Supplementary Fig. 11) showing clear TNT signals. Based on a reported vapour pressure of TNT of 7.3 × 10−4 Pa at room temperature, a saturated atmosphere approximates to 7 p.p.b. (0.007 mg l−1)42. Thus, this can be approximated to correspond to a molarity of around 3.1 × 10−8 M (Supplementary Note 2).

Finally, the photocatalytic properties of the TiO2 (R) were put to further use to add self-cleaning properties to the substrate. If a used substrate was further irradiated with 254 nm light then it could be cleaned of all organic residues, with the action of the hard ultraviolet and any generated surface electrons, returning it to a pristine state for further experiments. This process could be cycled without loss of analyte signal intensity (Fig. 3d; Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

We have demonstrated a powerful extension of SERS—PIERS—for the detection of ultra-trace levels of various small molecule analytes. Most important is the order of magnitude universal enhancement of the analyte signals, the recyclability of the substrates and the potential single-molecule detection that can be achieved. By combining the traditional metallic nanoparticles used for SERS, with a photoactive (pre-irradiated) TiO2 film, enhancement factors of an order of magnitude can be achieved over traditional SERS spectra, even for low Raman cross-section analytes. We propose that the mechanism of operation for this enhancement is due to Fermi level modification of the metallic NPs on the surface, improving chemical enhancement of the SERS signal and show that this is an early example of broad applicability of the chemical enhancement. We hope that this technique might be extended further through applying the same idea to carefully engineered plasmonic substrates. By coupling the increasing prevalence of portable Raman spectrometers and improved spectral analysis techniques with the sensitivity, robustness and inexpensive nature of PIERS, highly sensitive Raman analysis can become an integral part of not just homeland security, but also biological analysis, and environmental protection, where low Raman cross-sections can often prevent or hinder spectral monitoring.

Methods

Films were produced by drop casting Au or AgNPs onto metal oxide thin films. To produce the AuNP/TiO2 films detailed, 100 μl of a AuNP solution (∼4 × 10−10 M) in MeOH was dropped onto a 1 cm × 1 cm metal oxide substrate and allowed to dry in air. This gave an approximate coverage of 250 AuNPs per μm2.

Films were irradiated under 254 nm light (2 × 8 W bulbs at a distance of 13 cm) for 4 h, before application of fixed volumes of methanolic solutions of explosive, created from analytical standards, methanolic solutions of R6G, or aqueous solutions of glucose. In each case a fixed drop volume of 50 μl of analyte was applied and allowed to air dry on the film. Typical SERS spectra were collected by applying the drop to the film without the pre-irradiation step.

Raman spectra were measured after air-drying the films, on a Renishaw Raman inVia microscope with a 633 nm He–Ne excitation laser (1.9 mW when operated at 25% power, spot size ∼4.4 μm2). All samples were measured under identical conditions and multiple points were measured on each sample to ensure consistency between locations. Where appropriate, spectra are composites of multiple locations, however as this is a particle-enhanced technique, there were definite hotspots where stronger spectra were collected than on other regions, where weak, or no signal was observed. For direct comparison between PIERS and SERS spectra, normalisation of the Raman spectra was carried out using the standard deviations of the baseline signal for corresponding powder, SERS and PIERS spectra, within the range of 1,800–2,000 cm−1. Data was then scaled to obtain comparable signal-to-noise ratios. When plotting all spectra within a series are scaled to the same degree.

Additional protocols for chemical vapour deposition of films and particle synthesis, along with a list of characterization methods and set up details, are detailed in the Supplementary Methods.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Ben-Jaber, S. et al. Photo-induced enhanced Raman spectroscopy for universal ultra-trace detection of explosives, pollutants and biomolecules. Nat. Commun. 7:12189 doi: 10.1038/ncomms12189 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-11, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary Methods

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Steven Firth for useful discussion on the Raman spectra. SBJ acknowledges the support of the government of Saudi Arabia, Ministry of Interior, King Fahd Security College (KFSC), WJP is supported by EPSRC Doctoral Prize Fellowship EP/M506448/1, EC is supported by a Marie Curie fellowship. SAM and EC acknowledge the EPSRC Reactive Plasmonics project EP/M013812/1, the Office of Naval Research, the Royal Society, and the Lee-Lucas Chair in Physics.

Footnotes

Author contributions Experiments were designed by S.B-J., W.J.P., R.Q-C., E.C. and I.P.P. Materials synthesis was performed by W.J.P., C.S-V., E.C. and S.B-J. Raman experiments were performed by S.B-J. and R.Q-C., materials characterization by C.S-V., W.J.P. and R.Q-C., and plasmonic measurements by E.C. Explosives samples were provided, prepared and handled by N.A-K. Data analysis and interpretation was performed by S.B-J., W.J.P., R.Q-C., E.C., S.A.M. and I.P.P. The manuscript was written by W.J.P., R.Q-C., E.C., S.A.M. and I.P.P., with input from all the authors.

References

- Le Ru E. C. & Etchegoin P. G. Single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 63, 65–87 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ru E. & Etchegoin P. in Principles of Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy: and related plasmonic effects Elsevier (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Li J. F. et al. Shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nature 464, 392–395 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson E. M., Langhammer C., Zorić I. & Kasemo B. Nanoplasmonic probes of catalytic reactions. Science 326, 1091–1094 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stiles P. L., Dieringer J. A., Shah N. C. & Van Duyne R. P. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1, 601–626 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almaviva S. et al. Ultrasensitive RDX detection with commercial SERS substrates. J. Raman Spectrosc. 45, 41–46 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Hatab N. A., Eres G., Hatzinger P. B. & Gu B. Detection and analysis of cyclotrimethylenetrinitramine (RDX) in environmental samples by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 41, 1131–1136 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Kasera S., Herrmann L. O., Barrio J. D., Baumberg J. J. & Scherman O. A. Quantitative multiplexing with nano-self-assemblies in SERS. Sci. Rep. 4, 6785 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognalli N. G. et al. From single to multiple Ag-layer modification of Au nanocavity substrates: a tunable probe of the chemical surface-enhanced Raman scattering mechanism. ACS Nano 5, 5433–5443 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannini V., Fernández-Domínguez A. I., Heck S. C. & Maier S. A. Plasmonic nanoantennas: fundamentals and their use in controlling the radiative properties of nanoemitters. Chem. Rev. 111, 3888–3912 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrini L. & Graham D. Molecularly-mediated assemblies of plasmonic nanoparticles for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 7085–7107 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. et al. Tailoring surface plasmons of high-density gold nanostar assemblies on metal films for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Nanoscale 6, 616–623 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdelsalam M. E., Mahajan S., Bartlett P. N., Baumberg J. J. & Russell A. E. SERS at structured palladium and platinum surfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 7399–7406 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Ru E. C. & Etchegoin P. G. Quantifying SERS enhancements. MRS Bull. 38, 631–640 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Otto A., Timper J., Billmann J., Kovacs G. & Pockrand I. Surface roughness induced electronic raman scattering. Surf. Sci. Lett. 92, L55–L57 (1980). [Google Scholar]

- Persson B. N. J. On the theory of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Chem. Phys. Lett. 82, 561–565 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Xia L. et al. Visualized method of chemical enhancement mechanism on SERS and TERS. J. Raman Spectrosc. 45, 533–540 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Otto A. The ‘chemical' (electronic) contribution to surface-enhanced Raman scattering. J. Raman Spectrosc. 36, 497–509 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Persson B. N. J., Zhao K. & Zhang Z. Chemical Contribution to Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 207401 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandri I. Enhancing Raman scattering without plasmons: unprecedented sensitivity achieved by TiO2 shell-based resonators. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 5541–5544 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi J. R. & Birke R. L. Theory of surface-enhanced Raman scattering in semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 11120–11130 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Musumeci A. et al. SERS of semiconducting nanoparticles (TiO2 hybrid composites). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6040–6041 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontempi N., Carletti L., De Angelis C. & Alessandri I. Plasmon-free SERS detection of environmental CO2 on TiO2 surfaces. Nanoscale 8, 3226–3231 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldarola M. et al. Non-plasmonic nanoantennas for surface enhanced spectroscopies with ultra-low heat conversion. Nat. Commun. 6, 7915 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong S. et al. Noble metal-comparable SERS enhancement from semiconducting metal oxides by making oxygen vacancies. Nat. Commun. 6, 7800 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng C. et al. Hot carrier extraction with plasmonic broadband absorbers. ACS Nano 10, 4704–4711 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudnik L. M., Norrod K. L. & Rowlen K. L. SERS-active Ag films from photoreduction of Ag+ on TiO2. Appl. Spectrosc. 50, 422–424 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y.-C., Yu C.-C., Wang C.-C. & Juang L.-C. New application of photocatalytic TiO2 nanoparticles on the improved surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Chem. Phys. Lett. 420, 245–249 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Parkin I. P. & Palgrave R. G. Self-cleaning coatings. J. Mater. Chem. 15, 1689–1695 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- Primo A., Corma A. & García H. Titania supported gold nanoparticles as photocatalyst. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 886–910 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa T. & Kamat P. V. Charge separation and catalytic activity of Ag@TiO2 core−shell composite clusters under UV–irradiation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3928–3934 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezhenny S. et al. STM studies of defect production on the -(1 × 1) and -(1 × 2) surfaces induced by UV irradiation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 369, 152–158 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Henrich V. E., Dresselhaus G. & Zeiger H. J. Observation of two-dimensional phases associated with defect states on the surface of TiO2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 36, 1335–1339 (1976). [Google Scholar]

- Lin Z., Orlov A., Lambert R. M. & Payne M. C. New insights into the origin of visible light photocatalytic activity of nitrogen-doped and oxygen-deficient anatase TiO2. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 20948–20952 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo H. et al. Spatial charge separation in asymmetric structure of Au nanoparticle on TiO2 nanotube by light-induced surface potential imaging. Nano Lett. 14, 4413–4417 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onda K., Li B. & Petek H. Two-photon photoemission spectroscopy of TiO2 (110) surfaces modified by defects and O2 or H2O adsorbates. Phys. Rev. B 70, 045415 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Brown A. M., Sheldon M. T. & Atwater H. A. Electrochemical tuning of the dielectric function of Au nanoparticles. ACS Photonics 2, 459–464 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney P., Pérez-Juste J., Giersig M., Liz-Marzan L. M. & Pecharromán C. Drastic Surface Plasmon Mode Shifts in Gold Nanorods Due to Electron Charging. Plasmonics 1, 61–66 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Yang L. et al. Charge-transfer-induced surface-enhanced raman scattering on Ag−TiO2 nanocomposites. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 16226–16231 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian V., Wolf E. E. & Kamat P. V. Catalysis with TiO2/gold nanocomposites. Effect of metal particle size on the fermi level equilibration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 4943–4950 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdul-Karim N., Blackman C. S., Gill P. P., Wingstedt E. M. M. & Reif B. A. P. Post-blast explosive residue—a review of formation and dispersion theories and experimental research. RSC Adv. 4, 54354–54371 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Östmark H., Wallin S. & Ang H. G. Vapor pressure of explosives: a critical review. Propellants Explos. Pyrotech. 37, 12–23 (2012). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-11, Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Notes 1-2 and Supplementary Methods

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on request.