Abstract

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters form a large family of transmembrane proteins that facilitate the transport of specific substrates across membranes in an ATP-dependent manner. Transported substrates include lipids, lipopolysaccharides, amino acids, peptides, proteins, inorganic ions, sugars, and xenobiotics. Despite this broad array of substrates, the physiological substrate of many ABC transporters has remained elusive. ABC transporters are divided into seven subfamilies, A-G, based on sequence similarity and domain organization. Here we review the role of members of the ABCG subfamily in human disease and how the identification of disease genes helped to determine physiological substrates for specific ABC transporters. We focus on the recent discovery of mutations in ABCG2 causing hyperuricemia and gout, which has led to the identification of urate as a physiological substrate for ABCG2.

Keywords: ABCG2, urate, gout, hyperuricemia, GWAS

ABCG Family

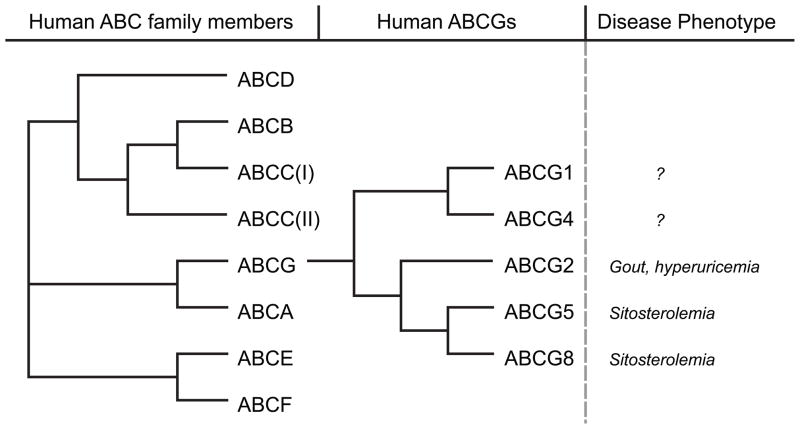

Members of the ABCG family are half transporters with one ABC cassette in the amino terminus followed by six putative transmembrane domains (please also see reviews on other ABC transporters as part of a minireview series in this issue [1–3]). Full transporters contain two ABC cassettes and 12 transmembrane domains. Half transporters assemble to homo- and hetero-dimeric complexes to form functional transporters. Fig. 1 provides an overview of the human ABC transporter superfamily and lists the members of the ABCG or White family, which is most closely related to the ABCA family. Currently, five members of the ABCG subfamily are known to exist in humans: ABCG1, ABCG2, ABCG4, ABCG5, and ABCG8.

Fig. 1. Phylogenetic tree of all human ABC genes and specifically the ABCG subgroup of genes.

(after [19, 66]). Disease phenotypes reported include only human diseases associated with specific ABCG mutations, not information from model organisms.

The ABCG1 gene is located on chromosome 21q22.3 [4]. Its product ABCG1 is found in multiple tissues and has a role in macrophage lipid transport [5]. ABCG2, mapped to chromosome 4q22, was initially identified in placenta tissue [6] and as a xenobiotic transporter from a human breast cancer cell line [7]. It was therefore also termed “breast cancer resistance protein” (BCRP). The ABCG4 gene is located on chromosome 11q23.3 [8, 9]. The gene product ABCG4 shows highest homology to ABCG1, and a role in macrophage lipid metabolism has also been proposed [9].

The human ABCG5 and ABCG8 genes, located adjacent to each other on chromosome 2p21, were both identified in the search of genetic causes of a rare autosomal-recessive lipid metabolism disorder, sitosterolemia [10].

ABCG-transporters and disease

Members of the ABCG family are known to play a role in lipid transport across membranes. Loss-of-function mutations in ABCG5 or ABCG8 cause sitosterolemia, a disorder characterized by the accumulation of plant and fish sterols including cholesterol [10–12]. Clinical characteristics of sitosterolemia are xanthomatosis and premature atherosclerosis, resulting in early onset of cardiovascular disease and lethal myocardial infarction [13]. Mutations in ABCG5 or ABCG8 cause increased intestinal absorption and decreased biliary elimination of plant sterols and cholesterol, leading to a 50 to 200-fold increase in plasma plant sterol concentrations [13, 14]. The encoded proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 form obligate heterodimers that are expressed in the apical membrane of enterocytes and in the canicular membrane of hepatocytes [15]. They limit the absorption of plant sterols and cholesterol by secreting these sterols from enterocytes back into the intestinal lumen, and by excretion of sterols from hepatocytes into bile. Disruption of ABCG5 and ABCG8 in mice results in a 3-fold increase in the fractional absorption of plant sterols, a 30% increase in plasma sitosterol levels, and a reduction in biliary cholesterol levels [16]. Thus these mice display many characteristics seen in patients with sitosterolemia. In accordance with the phenotypes observed upon disrupted function of ABCG5 and ABCG8 in humans or mice, it was recently shown that sterols are the direct substrates of ABCG5 and ABCG8. Inside-out membrane vesicles prepared from Sf9 insect cells over-expressing ABCG5 and 8, or from liver membranes showed ATP-dependent transfer of both cholesterol and sitosterol [17, 18].

To date no functional mutations in ABCG1 and ABCG4 have been linked to any monogenic human disease; although ABCG1 has been implicated in cardiovascular disease, obesity and diabetes (reviewed in [19]). Abcg1−/− mice on a high-cholesterol diet display an attenuated endothelium-dependent arterial vasorelaxation as well as reduced activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase, consistent with a role of ABCG1 in maintaining endothelial cell function by promoting efflux of cholesterol and 7-oxysterols [20]. In contrast, ABCG4 is highly expressed in the central nervous system. Detailed studies of the brains of Abcg4−/− mice (<1 year old) did not identify any pathological changes, however [19]. Both proteins have been shown to transport lipids including cholesterol, but their precise role in vivo remains to be elucidated. It is of great interest whether future studies will establish a role of these transporters in inherited human disorders.

Discovery of ABCG2 variants in association studies of human disease

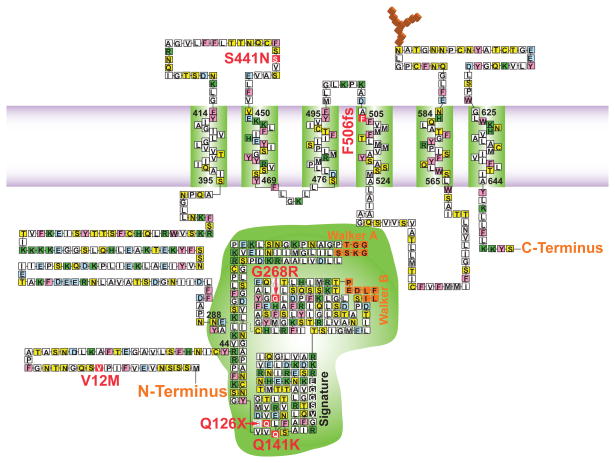

ABCG2 was first identified as a multidrug resistance protein (Fig. 2) [7]. It has been shown to transport a wide range of structurally and functionally diverse substrates such as chemotherapeutics, antibiotics and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors. Yet, physiological substrates and the roles of ABCG2 in vivo had remained elusive until very recently. As was the case for ABCG5 and ABCG8, an important physiological function of ABCG2 was uncovered through genetic studies of human disease. In a series of genetic and physiological studies over the past three years, it was established that ABCG2 functions as a novel urate transporter that promotes urate excretion in the human kidney.

Fig. 2. Topographical representation of the ABCG2 monomer in the plasma membrane.

Transmembrane domains experimentally determined by Wang and colleagues (2008) [67]; Nucleotide binding domain (NBD) begins at Y44 and ends at residue N288 [68]. The Walker A and B and ABC signature motif of the nucleotide binding domain are indentified, as are the 6 human polymorphisms associated with hyperuricemia and gout (in red) [21, 41]. Amino acid residues: pink = aromatic; green = + charged; light blue = − charged; blue = nonpolar; yellow = polar residues.

A genome-wide association study among more than 11,000 individuals of European ancestry, including replication in an additional 11,000 European ancestry and 3800 African American study participants, identified common alleles in ABCG2 as associated with serum urate levels and risk of gout [21]. Gout is a common form of arthritis with a prevalence of about 1–3% in Western countries [22, 23]. Patients with gout experience very painful attacks caused by the precipitation of monosodium urate crystals in joints, which triggers subsequent inflammation. Elevated serum urate levels therefore are a key risk factor for gout. Earlier studies showed that serum urate levels are highly heritable [24]. In fact, the majority of inter-individual variation of urate levels in a population can be explained by additive genetic effects. A genome-wide association study was initiated among individuals participating in three large, population-based prospective studies (Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study, Framingham Heart Study, Rotterdam Study) in an effort to discover genes that might explain the genetic effects on serum urate levels. Each study participant had serum urate levels measured and genotyping performed either as part of a high-throughput single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) chip or targeted replication genotyping. Gout status was ascertained by self-report or based on the intake of gout-specific medication [21]. Of more than 500,000 SNPs surveyed, the ABCG2 variant with the strongest effect on serum urate concentrations was the SNP rs2231142: each additional copy of the minor T allele was associated with approximately 0.25 standard deviations higher mean serum urate concentrations among individuals of European ancestry (p= 3*10−60), corresponding to approximately 0.30 mg/dl higher mean serum urate per copy of the T allele (Table 1). The odds of gout were increased by 74% with each copy of the T allele (OR 1.74, 95% confidence interval 1.51–1.99, p=4*10−15). The association between the risk allele and serum urate and gout was significantly stronger in men compared to women [21,25].

Table 1.

Effect sizes of the ABCG2 rs2231142 (Q141K) variant on risk of gout and mean urate levels in study populations of different ancestry

| Study sample ethnicity | Sample Size | Risk allele frequency (T) | Odds Ratio for gout per T allele, 95% CI | Effect on mean serum urate per T allele | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European ancestry | 22,871 | 0.11 | 1.74 | 0.24 standard deviation changes | [21] |

| European ancestry | 28,141 | 0.11 | NA | 0.17 z-score units | [44] |

| European ancestry | 28,283 | 0.11* | 1.86 | 0.30 mg/dl | [45] |

| European ancestry | 4,492 | 0.11–0.12 | NA | 0.34 mg/dl | [62] |

| European ancestry | 2,246 | 0.1 (controls), 0.14 (cases) | 1.37 | NA | [63] |

| African American | 3,843 | 0.03 | 1.71 | 0.22 standard deviations | [21] |

| Japanese | 739 | 0.32 | 2.5 in a subset of gout patients | appr. 0.4 mg/dl | [41] |

| Japanese | 3,923 | 0.31 | 1.37 for genotype TG, 4.37 for genotype TT | [26] | |

| Japanese | 5,165 | 0.23–0.30 | NA | 0.1 mg/dl per risk allele | [64] |

| New Zealand population | Cases/con Trolls: 185/284 (Maori), 173/129 Pacific Islanders, 214/562 Caucasian | 1.08 (Maori), 2.80 (Pacific Islanders), 2.20 (Caucasian) | [65] |

Since this first study, the effect of the rs2231142 T allele on mean serum urate levels and the risk of gout has been replicated in many diverse study populations and is consistently observed with comparable effect sizes (Table 1). Replication of a finding in study populations of different ancestry, where risk allele frequency and correlation patterns between nearby genomic variants may differ, is an important feature of a functional genetic variant. Interestingly, the allele frequency of the T risk allele in a Japanese study population was reported as 31% [26], which is approximately three times more common than the T allele frequency observed in individuals of European ancestry. While the prevalence of gout in Japan is lower than in countries where a Western diet is consumed, the prevalence of gout among U.S. individuals of Asian ancestry has been reported as three times higher compared to U.S. individuals of European ancestry [27].

Physiological Function of ABCG2

A connection between ABCG2 and urate metabolism or gout had not been described until this first genome-wide association study. It was however known that human ABCG2 is expressed in the apical membrane of human proximal tubule cells [28], the main site of urate handling in the human kidney. We therefore investigated whether urate is a physiological substrate of ABCG2, and whether the Q141K variant, encoded by rs2231142, leads to altered urate transport and as a consequence to elevated serum urate levels and increased risk of gout.

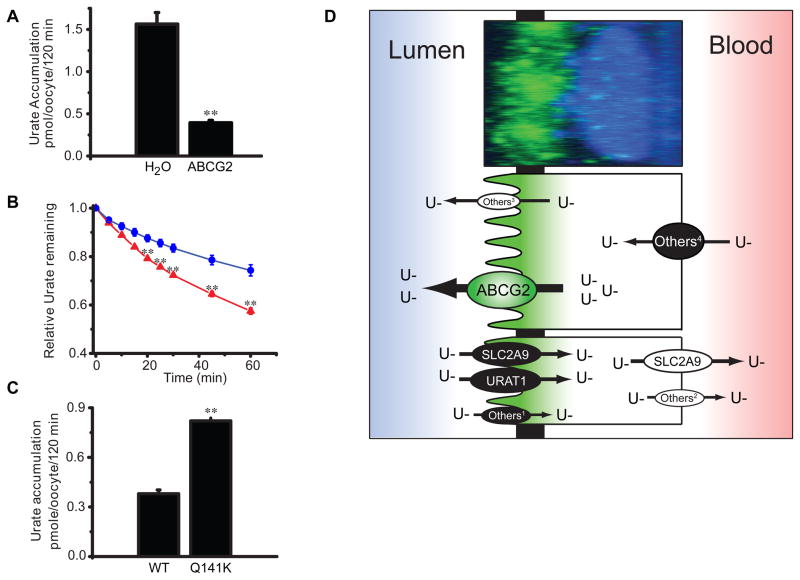

In order to test whether ABCG2 was a yet unknown urate transporter, ABCG2 was expressed in Xenopus oocytes [29]. Accumulation of radiolabeled urate in oocytes expressing ABCG2 was decreased by 75% compared with water-injected control coocytes (Fig. 3A). The reduced urate accumulation was caused by ABCG2-mediated urate efflux from cells, rather than by the inhibition of urate uptake as shown in experiments monitoring the decrease of intracellular urate over time in oocytes preloaded with radiolabeled urate (Fig. 3B). Although it was known that the major site of urate excretion in humans is the proximal tubule in the kidney, the molecular identity of the transporters mediating urate secretion at the apical membrane of proximal tubular cells had only been poorly understood. To study ABCG2 function at this location, urate accumulation and localization of ABCG2 was studied in native LLC-PK1 cells, a porcine proximal tubule cell line. These experiments revealed that ABCG2 mediates the apical secretion of urate in proximal tubule cells (Fig. 3D). A similar function and localization has been shown for MRP4 [30, 31], but polymorphisms in MRP4 have not been linked to hyperuricemia and gout in humans.

Fig. 3. ABCG2 is a urate transporter.

(A) C-14 urate accumulation from Xenopus oocytes injected with mRNA coding for either ABCG2 or H2O controls. (B) Urate efflux in oocytes incubated overnight in 500 μM C-14 urate as relative efflux over time (blue = control; red = ABCG2). (C) Urate accumulation in oocytes expressing either the wild type ABCG2 or the mutant Q141K ABCG2. (**p<0.01, ± S.E.M.)(A–C originally from [29]; © 2009 by the National Academy of Sciences of the USA). (D) Model of urate transport in the proximal tubule of the human kidney overlaying fluorescent micrograph of LLCPK-1 proximal tubule cell with endogenous ABCG2 labeled in green and the nucleus in blue. Proteins influencing urate absorption and secretion and with significance for human diseases are shown with the direction of urate transport indicated [21, 69, 70]. Other transporters expressed in the human kidney and shown to transport urate in model systems: 1OAT4; 2OAT1, OAT3; 3MRP4; 4OAT1, OAT3 [71, 72].

Given the vast literature on ABCG2 with dozens of structurally diverse substrates it appears surprising at first glance that urate was not found to be a physiological substrate earlier. Notably, ABCG2 knock-out mice do not develop gout. One of the reasons for urate staying under the radar of ABCG2 research may be that gout is a complex genetic disease with multiple contributing genetic and environmental factors. More importantly though there are striking species differences in purine metabolism within the animal kingdom. Urate is the end product of purine metabolism in humans. Humans and higher primates have much higher serum urate levels than other mammals because they lack the enzyme uricase, which converts urate into allantoin [32]. Therefore genetic factors that predispose to hyperuricemia and gout cannot be easily studied in rodent models.

Q141K is a functional variant in ABCG2

Several lines of evidence in the initial genome-wide association study by Dehghan and colleagues suggested that the rs2231142 variant may be functional. First, the variant is located in exon 5 of ABCG2 and leads to a glutamine-to-lysine amino acid substitution (Q141K) in ABCG2. This substitution is predicted to have a possibly damaging effect by the functional prediction program PolyPhen-2 [33]. Secondly, the glutamine residue at position 141 is highly conserved across species. No other common variants in the ABCG2 gene region showed association with serum urate levels after accounting for the effect of rs2231142 [21, 29].

However, while genome-wide association studies have been extremely successful at establishing associations between common SNPs and a multitude of complex diseases [34], these studies cannot establish whether a disease-associated SNP is causally related to the disease or merely a naturally occurring genetic marker that is correlated with another, unknown functional variant. To test whether the rs2231142 is such a functional variant, the transport capacity of the encoded Q141K mutation was compared to that of wild type ABCG2. Oocytes expressing ABCG2 Q141K showed 54% reduced urate transport rates compared with oocytes expressing wild type ABCG2 (Fig. 3C). This is consistent with previous studies showing impaired transport of chemotherapeutic agents by ABCG2 Q141K [35, 36] (and reviewed in [37]). While it is difficult to compare the results from different transport assays and substrates, the reduction of transport of the Q141K variant compared to wild type ABCG2 appears to be of similar magnitude. The Q141 residue is located in the nucleotide-binding domain of ABCG2 (Fig. 2), and Q141K ABCG2 expression is significantly lower than wildtype when overexpressed in mammalian cells [35, 36, 38, 39]. Interestingly, the F508 mutation in CFTR, a related ABC transporter, is located right next to this position in the nucleotide-binding domain and is commonly mutated in cystic fibrosis patients [40]. And like the Q141K ABCG2 mutation, expression of the deleted F508 CFTR mutant is significantly lower than wildtype suggesting a common pathophysiology (Woodward unpublished observations).

The role of ABCG2 as a urate transporter with mutations leading to hyperuricemia and gout was recently confirmed and further investigated by Matsuo and colleagues [41]. The investigators of this study identified several non-synonymous coding variants in ABCG2 through sequencing of the ABCG2 gene in 90 hyperuricemia patients in a Japanese population. In addition to Q141K, Q126X was identified as a novel loss-of-function variant. Q126X was assigned to a different haplotype than Q141K and shown to increase gout risk (odds ratio 5.97) to an even greater extent than the Q141K variant. In addition, 10% of the gout patients studied had genotype combinations of the Q141K and Q126X variants that resulted in more than a 75% reduction of ABCG2 function when compared to patients that were homozygous for the non-risk allele at both variants (odds ratio 25.8, 95% confidence interval 10.3–64.6).

Many additional SNPs and their role in ABCG2 function have been analyzed [37, 42], but these studies have not addressed the impact of other SNPs in urate transport and gout. Future studies will have to test whether additional functional SNPs also affect serum urate concentrations in humans.

Urate transport is complex: in the kidney, urate transport is bi-directional and involves multiple different transport and regulatory proteins [32, 43]. This is reflected in the complex genetic architecture of serum urate levels and risk of gout: two recent large genome-wide association studies identified variants in multiple genes associated with serum urate concentrations (SLC2A9, ABCG2, SLC17A1, SLC22A11, SLC22A12, SLC16A9, GCKR, LRRC16A, PDZK1, the R3HDM2-INHBC region, and RREB1) [44, 45]. The effect of the individual common risk alleles in these genes on mean serum urate concentrations and the risk of gout is modest. The range of the phenotypic variation in serum urate levels in the studied populations that could be explained by the individual genetic variants ranged from 0.1% to 3.5%. However, the effect of urate-increasing alleles at different genomic loci can add up: Yang and colleagues estimated from several large population-based studies that mean urate levels increased from approximately 4.5 to 6.2 mg/dl across a genetic score composed of the risk alleles at 8 different genomic loci [45]. Similarly, the prevalence of gout increased from 2% to more than 20% at the upper extreme of the risk score. Some of the genes identified in the two large studies mentioned above encode for known urate transporters (SLC2A9, ABCG2, SLC17A1, SLC22A11, SLC22A12) or regulators thereof (PDZK1). For the remaining genes, little is known about a possible connection of the gene product to urate metabolism in humans and therefore constitutes a new area for future research.

ABCG2 function in other tissues

ABCG2’s physiological function has been difficult to identify because of its large number of known substrates and varied tissue expression. Suggested physiological roles include functioning as a xenobiotic transporter, conferring xenobiotic protection in tissues like the liver, intestine, placenta, and CNS [37]; and as a transporter of heme and other porphyrins, preventing their accumulation in erythrocytes and stem cells [46, 47]. As noted above ABCG2 plays a significant role in urate transport in the human kidney, but does ABCG2 expression in other tissues fit with this newly postulated function? Here we would like to discuss the putative physiological role of ABCG2-mediated urate transport in other tissues. In addition to the kidney, ABCG2 is expressed at high levels in the liver, at the blood brain barrier, in the placenta, and in mammary glands. An examination of ABCG2 at each of these locations suggests ABCG2 expression is consistent with sites of urate transport. In human hepatocytes, ABCG2 is expressed in the basolateral membrane [48] orientated to mediate efflux into the biliary canaliculus. Though ABCG2 is effectively situated to remove drugs and toxins from the liver, it is also well situated to export urate out of the liver via the biliary system, a known urate excretion pathway [49]. ABCG2, in addition to the urate transporter MRP4 [31], are the only identified urate transporters positioned to secrete urate into the biliary system and thus ABCG2 could be playing a substantial role in the liver mediated urate excretion pathway. At the blood brain barrier, ABCG2 is expressed on the luminal membrane of endothelial cells, seemingly well positioned to protect the brain from accumulating xenotoxins [50]. However there is also ample evidence that misregulation of urate at the blood brain barrier has profound effects on brain function and health. Cerebrospinal fluid urate levels and serum urate levels are correlated [51, 52] but urate concentration in cerebrospinal fluid is only 7% of that in serum [52] suggesting an important role for urate secretion from the cerebrospinal fluid. Higher serum urate levels are associated with cognitive dysfunction [53] but are also protective against developing Parkinson’s disease [52]. Thus a tight regulation of cerebrospinal fluid urate appears important. High expression of ABCG2 at the blood brain barrier may help maintain appropriate urate concentrations in the brain and the cerebrospinal fluid.

Pregnancy has a profound effect on ABCG2 expression at two sites. First, ABCG2 is expressed highly in the apical membrane of placental syncytiotrophoblasts and is hypothesized to aid in the protection of the fetus from toxins or to regulate fetal estrogen levels by transporting estrogen precursor molecules [54]. However, ABCG2 mediated efflux of urate from the placenta may be critical for normal fetal development. It was recently reported that high urate levels in amniotic fluid correlated with lower birth weights, finding a 2 mg/dl decrease in amniotic urate results in a 120 g increase in birth weight [55]. Secondly, pregnancy and lactation increases ABCG2 expression in mammary gland alveolar epithelial cells. This can result in the concentrating of xenotoxins, if present in the mother, into breast milk [56], a seemingly undesirable outcome for a nursing infant. This apparent contradiction prompted the proposal that ABCG2 may be mostly transporting non-toxic substitutes like riboflavin [57]. Yet ABCG2 knock-out models show no reduction of this vitamin in breast milk [58]. In contrast, there is some evidence that human breast milk plays an important role in delivering antioxidants, including urate, to infants [59]. Interestingly, while human breast milk contains urate, it does not contain orotic acid, which is found in high concentrations in other mammalian milk [60, 61]. Orotic acid is a strong uricosuric compound, and its disappearance from human milk is consistent with the evolutionarily conserved loss of uricase function to increase urate levels in humans. In summary, a role of ABCG2-mediated urate secretion in several non-renal tissues is conceivable and needs to be investigated in more detail.

Pharmacological modulation of ABCG2, both inhibition and activation, has been proposed as therapeutic strategies for numerous human diseases. For instance, inhibition of ABCG2 has been tested to overcome multidrug resistance in cancer therapy. However, based on the function of ABCG2 in urate excretion, one possible side effect of ABCG2 inhibitors could be increased serum urate concentrations and gout attacks. Further studies on ABCG2 are needed to learn more about its function in different tissues and the relevance of additional physiological substrates. These studies may help to predict therapeutic effects as well as side effects of drugs targeting ABCG2.

Future perspectives and conclusion

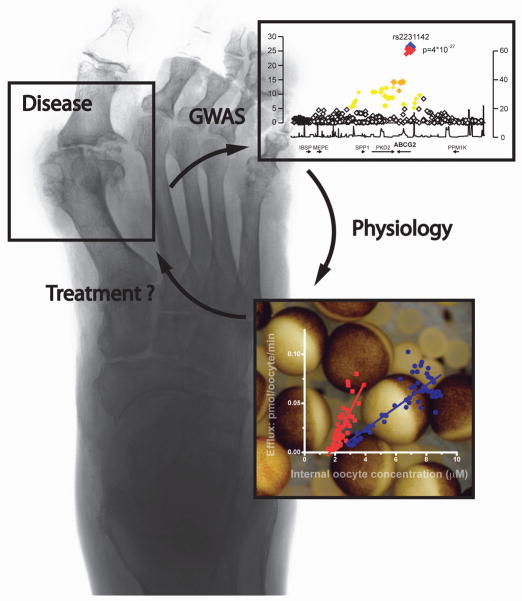

In summary, mutations in members of the ABCG family have led to the identification of physiological substrates and functions of these transporters. We anticipate that future studies will continue to uncover additional novel physiological substrates and functions for ABC transporters and define additional roles in human disease. The powerful combination of genetic and physiological approaches may not only identify novel mechanisms but may also help to identify novel therapeutic targets. ABCG2 represents an attractive drug target since pharmacological activation of ABCG2 may help to promote urate excretion from the body. The discovery of ABCG2 as a novel urate transporter is a prime example for translational research. Hopefully, the fast translation from beside to bench will eventually lead back to the bedside and benefit patients suffering from gout (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The cycle of translational research can begin with the description of a disease phenotype like the destruction of joints that occurs in patients with gout from urate crystal deposition. Genome-wide association studies allowed the identification of genes that associate with elevated serum urate levels and gout. Subsequent in-depth physiological characterization of the gene and its protein product lays the foundation for an improved understanding of physiology and pathophysiology and may reveal a therapeutic target. Finally, drug development can be attempted in order to better treat hyperuricemia or gout.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the work of many others whose work we could not cite due to space constraints. OMW was supported by NIDDK: DK032753-25A1, AK was supported by the Emmy Noether programme of DFG and MK was supported by DFG KFO 201 and by Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation.

References

- 1.Ueda K. Function and regulation of ABCA1. FEBS J. 2011;XX:XXXX. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Callaghan R. Translocase ABCA4: seeing is believing. FEBS J. 2011;XX:XXXX. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z-S. Multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs/ABCCs) in cancer chemotherapy and genetics disease. FEBS J. 2011;XX:XXXX. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen H, Rossier C, Lalioti MD, Lynn A, Chakravarti A, Perrin G, Antonarakis SE. Cloning of the cDNA for a human homologue of the Drosophila white gene and mapping to chromosome 21q22.3. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;59:66–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klucken J, Buchler C, Orso E, Kaminski WE, Porsch-Ozcurumez M, Liebisch G, Kapinsky M, Diederich W, Drobnik W, Dean M, et al. ABCG1 (ABC8), the human homolog of the Drosophila white gene, is a regulator of macrophage cholesterol and phospholipid transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:817–822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allikmets R, Schriml LM, Hutchinson A, Romano-Spica V, Dean M. A human placenta-specific ATP-binding cassette gene (ABCP) on chromosome 4q22 that is involved in multidrug resistance. Cancer Res. 1998;58:5337–5339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle LA, Yang W, Abruzzo LV, Krogmann T, Gao Y, Rishi AK, Ross DD. A multidrug resistance transporter from human MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15665–15670. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.26.15665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Annilo T, Tammur J, Hutchinson A, Rzhetsky A, Dean M, Allikmets R. Human and mouse orthologs of a new ATP-binding cassette gene, ABCG4. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;94:196–201. doi: 10.1159/000048816. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Engel T, Lorkowski S, Lueken A, Rust S, Schluter B, Berger G, Cullen P, Assmann G. The human ABCG4 gene is regulated by oxysterols and retinoids in monocyte-derived macrophages. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;288:483–488. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5756. S0006-291X(01)95756-0 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berge KE, Tian H, Graf GA, Yu L, Grishin NV, Schultz J, Kwiterovich P, Shan B, Barnes R, Hobbs HH. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science. 2000;290:1771–1775. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1771. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dean M. The genetics of ATP-binding cassette transporters. Methods Enzymol. 2005;400:409–429. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)00024-8. S0076-6879(05)00024-8 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee MH, Lu K, Hazard S, Yu H, Shulenin S, Hidaka H, Kojima H, Allikmets R, Sakuma N, Pegoraro R, et al. Identification of a gene, ABCG5, important in the regulation of dietary cholesterol absorption. Nat Genet. 2001;27:79–83. doi: 10.1038/83799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudhop T, von Bergmann K. Sitosterolemia--a rare disease. Are elevated plant sterols an additional risk factor? Z Kardiol. 2004;93:921–928. doi: 10.1007/s00392-004-0165-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berge KE. Sitosterolemia: a gateway to new knowledge about cholesterol metabolism. Ann Med. 2003;35:502–511. doi: 10.1080/07853890310014588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graf GA, Li WP, Gerard RD, Gelissen I, White A, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Coexpression of ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 permits their transport to the apical surface. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:659–669. doi: 10.1172/JCI16000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu L, Hammer RE, Li-Hawkins J, Von Bergmann K, Lutjohann D, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Disruption of Abcg5 and Abcg8 in mice reveals their crucial role in biliary cholesterol secretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16237–16242. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252582399. 252582399 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang J, Sun F, Zhang DW, Ma Y, Xu F, Belani JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH, Xie XS. Sterol transfer by ABCG5 and ABCG8: in vitro assay and reconstitution. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27894–27904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605603200. M605603200 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Zhang DW, Lei Y, Xu F, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH, Xie XS. Purification and reconstitution of sterol transfer by native mouse ABCG5 and ABCG8. Biochemistry. 2008;47:5194–5204. doi: 10.1021/bi800292v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tarr PT, Tarling EJ, Bojanic DD, Edwards PA, Baldan A. Emerging new paradigms for ABCG transporters. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1791:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.01.007. S1388-1981(09)00011-0 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terasaka N, Yu S, Yvan-Charvet L, Wang N, Mzhavia N, Langlois R, Pagler T, Li R, Welch CL, Goldberg IJ, et al. ABCG1 and HDL protect against endothelial dysfunction in mice fed a high-cholesterol diet. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3701–3713. doi: 10.1172/JCI35470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehghan A, Kottgen A, Yang Q, Hwang SJ, Kao WL, Rivadeneira F, Boerwinkle E, Levy D, Hofman A, Astor BC, et al. Association of three genetic loci with uric acid concentration and risk of gout: a genome-wide association study. Lancet. 2008;372:1953–1961. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61343-4. S0140-6736(08)61343-4 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Choi HK, Mount DB, Reginato AM. Pathogenesis of gout. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:499–516. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-7-200510040-00009. [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG, Arnold LM, Choi H, Deyo RA, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Hochberg MC, Hunder GG, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:26–35. doi: 10.1002/art.23176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Q, Guo CY, Cupples LA, Levy D, Wilson PW, Fox CS. Genome-wide search for genes affecting serum uric acid levels: the Framingham Heart Study. Metabolism. 2005;54:1435–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.05.007. S0026-0495(05)00215-5 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tanaka Y, Slitt AL, Leazer TM, Maher JM, Klaassen CD. Tissue distribution and hormonal regulation of the breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp/Abcg2) in rats and mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;326:181–187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.11.012. S0006-291X(04)02567-7 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamagishi K, Tanigawa T, Kitamura A, Kottgen A, Folsom AR, Iso H. The rs2231142 variant of the ABCG2 gene is associated with uric acid levels and gout among Japanese people. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1461–1465. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq096. keq096 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krishnan E, Lienesch D, Kwoh CK. Gout in ambulatory care settings in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2008;35:498–501. [pii] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huls M, Brown CD, Windass AS, Sayer R, van den Heuvel JJ, Heemskerk S, Russel FG, Masereeuw R. The breast cancer resistance protein transporter ABCG2 is expressed in the human kidney proximal tubule apical membrane. Kidney Int. 2008;73:220–225. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002645. 5002645 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodward OM, Kottgen A, Coresh J, Boerwinkle E, Guggino WB, Kottgen M. Identification of a urate transporter, ABCG2, with a common functional polymorphism causing gout. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:10338–10342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901249106. 0901249106 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Aubel RA, Smeets PH, Peters JG, Bindels RJ, Russel FG. The MRP4/ABCC4 gene encodes a novel apical organic anion transporter in human kidney proximal tubules: putative efflux pump for urinary cAMP and cGMP. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:595–603. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Aubel RA, Smeets PH, van den Heuvel JJ, Russel FG. Human organic anion transporter MRP4 (ABCC4) is an efflux pump for the purine end metabolite urate with multiple allosteric substrate binding sites. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2005;288:F327–333. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00133.2004. 00133.2004 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anzai N, Kanai Y, Endou H. New insights into renal transport of urate. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:151–157. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e328032781a. 00002281-200703000-00012 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, Ramensky VE, Gerasimova A, Bork P, Kondrashov AS, Sunyaev SR. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. nmeth0410-248 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manolio TA. Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:166–176. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0905980. 363/2/166 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mizuarai S, Aozasa N, Kotani H. Single nucleotide polymorphisms result in impaired membrane localization and reduced atpase activity in multidrug transporter ABCG2. Int J Cancer. 2004;109:238–246. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morisaki K, Robey RW, Ozvegy-Laczka C, Honjo Y, Polgar O, Steadman K, Sarkadi B, Bates SE. Single nucleotide polymorphisms modify the transporter activity of ABCG2. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2005;56:161–172. doi: 10.1007/s00280-004-0931-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polgar O, Robey RW, Bates SE. ABCG2: structure, function and role in drug response. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4:1–15. doi: 10.1517/17425255.4.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Furukawa T, Wakabayashi K, Tamura A, Nakagawa H, Morishima Y, Osawa Y, Ishikawa T. Major SNP (Q141K) variant of human ABC transporter ABCG2 undergoes lysosomal and proteasomal degradations. Pharm Res. 2009;26:469–479. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9752-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Imai Y, Nakane M, Kage K, Tsukahara S, Ishikawa E, Tsuruo T, Miki Y, Sugimoto Y. C421A polymorphism in the human breast cancer resistance protein gene is associated with low expression of Q141K protein and low-level drug resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:611–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuller CM, Benos DJ. Cftr! Am J Physiol. 1992;263:C267–286. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1992.263.2.C267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsuo H, Takada T, Ichida K, Nakamura T, Nakayama A, Ikebuchi Y, Ito K, Kusanagi Y, Chiba T, Tadokoro S, et al. Common defects of ABCG2, a high-capacity urate exporter, cause gout: a function-based genetic analysis in a Japanese population. Sci Transl Med. 2009;1:5ra11. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000237. 1/5/5ra11 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koshiba S, An R, Saito H, Wakabayashi K, Tamura A, Ishikawa T. Human ABC transporters ABCG2 (BCRP) and ABCG4. Xenobiotica. 2008;38:863–888. doi: 10.1080/00498250801986944. 795429507 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.So A, Thorens B. Uric acid transport and disease. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1791–1799. doi: 10.1172/JCI42344. 42344 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kolz M, Johnson T, Sanna S, Teumer A, Vitart V, Perola M, Mangino M, Albrecht E, Wallace C, Farrall M, et al. Meta-analysis of 28,141 individuals identifies common variants within five new loci that influence uric acid concentrations. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang Q, Kottgen A, Dehghan A, Smith AV, Glazer NL, Chen MH, Chasman DI, Aspelund T, Eiriksdottir G, Harris TB, et al. Multiple Genetic Loci Influence Serum Urate And Their Relationship With Gout and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.109.934455. CIRCGENETICS.109.934455 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jonker JW, Buitelaar M, Wagenaar E, Van Der Valk MA, Scheffer GL, Scheper RJ, Plosch T, Kuipers F, Elferink RP, Rosing H, et al. The breast cancer resistance protein protects against a major chlorophyll-derived dietary phototoxin and protoporphyria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:15649–15654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202607599. 202607599 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Krishnamurthy P, Ross DD, Nakanishi T, Bailey-Dell K, Zhou S, Mercer KE, Sarkadi B, Sorrentino BP, Schuetz JD. The stem cell marker Bcrp/ABCG2 enhances hypoxic cell survival through interactions with heme. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24218–24225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313599200. M313599200 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ieiri I, Higuchi S, Sugiyama Y. Genetic polymorphisms of uptake (OATP1B1, 1B3) and efflux (MRP2, BCRP) transporters: implications for inter-individual differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of statins and other clinically relevant drugs. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2009;5:703–729. doi: 10.1517/17425250902976854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kountouras J, Magoula I, Tsapas G, Liatsis I. The effect of mannitol and secretin on the biliary transport of urate in humans. Hepatology. 1996;23:229–233. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v23.pm0008591845. S0270-9139(96)00038-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scherrmann JM. Expression and function of multidrug resistance transporters at the blood-brain barriers. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2005;1:233–246. doi: 10.1517/17425255.1.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowman GL, Shannon J, Frei B, Kaye JA, Quinn JF. Uric acid as a CNS antioxidant. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;19:1331–1336. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-1330. U29P765046470236 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlesinger I, Schlesinger N. Uric acid in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:1653–1657. doi: 10.1002/mds.22139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vannorsdall TD, Jinnah HA, Gordon B, Kraut M, Schretlen DJ. Cerebral ischemia mediates the effect of serum uric acid on cognitive function. Stroke. 2008;39:3418–3420. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.521591. STROKEAHA.108.521591 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mao Q. BCRP/ABCG2 in the placenta: expression, function and regulation. Pharm Res. 2008;25:1244–1255. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9537-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gao T, Zablith NR, Burns DH, Skinner CD, Koski KG. Second trimester amniotic fluid transferrin and uric acid predict infant birth outcomes. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:810–814. doi: 10.1002/pd.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jonker JW, Merino G, Musters S, van Herwaarden AE, Bolscher E, Wagenaar E, Mesman E, Dale TC, Schinkel AH. The breast cancer resistance protein BCRP (ABCG2) concentrates drugs and carcinogenic xenotoxins into milk. Nat Med. 2005;11:127–129. doi: 10.1038/nm1186. nm1186 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Herwaarden AE, Schinkel AH. The function of breast cancer resistance protein in epithelial barriers, stem cells and milk secretion of drugs and xenotoxins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.11.007. S0165-6147(05)00309-3 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Herwaarden AE, Wagenaar E, Merino G, Jonker JW, Rosing H, Beijnen JH, Schinkel AH. Multidrug transporter ABCG2/breast cancer resistance protein secretes riboflavin (vitamin B2) into milk. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:1247–1253. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01621-06. MCB.01621-06 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aycicek A, Erel O, Kocyigit A, Selek S, Demirkol MR. Breast milk provides better antioxidant power than does formula. Nutrition. 2006;22:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.12.011. S0899-9007(06)00110-9 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ferreira IM. Quantification of non-protein nitrogen components of infant formulae and follow-up milks: comparison with cows’ and human milk. Br J Nutr. 2003;90:127–133. doi: 10.1079/bjn2003882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Indyk HE, Woollard DC. Determination of orotic acid, uric acid, and creatinine in milk by liquid chromatography. J AOAC Int. 2004;87:116–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brandstatter A, Lamina C, Kiechl S, Hunt SC, Coassin S, Paulweber B, Kramer F, Summerer M, Willeit J, Kedenko L, et al. Sex and age interaction with genetic association of atherogenic uric acid concentrations. Atherosclerosis. 2010;210:474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.12.013. S0021-9150(09)01021-1 [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stark K, Reinhard W, Grassl M, Erdmann J, Schunkert H, Illig T, Hengstenberg C. Common polymorphisms influencing serum uric acid levels contribute to susceptibility to gout, but not to coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tabara Y, Kohara K, Kawamoto R, Hiura Y, Nishimura K, Morisaki T, Kokubo Y, Okamura T, Tomoike H, Iwai N, et al. Association of four genetic loci with uric acid levels and reduced renal function: the J-SHIPP Suita study. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32:279–286. doi: 10.1159/000318943. 000318943 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Phipps-Green AJ, Hollis-Moffatt JE, Dalbeth N, Merriman ME, Topless R, Gow PJ, Harrison AA, Highton J, Jones PB, Stamp LK, et al. A strong role for the ABCG2 gene in susceptibility to gout in New Zealand Pacific Island and Caucasian, but not Maori, case and control sample sets. Hum Mol Genet. 2010 doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddq412. ddq412 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dean MC. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. NCBI; Bethesda, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang H, Lee EW, Cai X, Ni Z, Zhou L, Mao Q. Membrane topology of the human breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) determined by epitope insertion and immunofluorescence. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13778–13787. doi: 10.1021/bi801644v. [pii] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li YF, Polgar O, Okada M, Esser L, Bates SE, Xia D. Towards understanding the mechanism of action of the multidrug resistance-linked half-ABC transporter ABCG2: a molecular modeling study. J Mol Graph Model. 2007;25:837–851. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2006.08.005. S1093-3263(06)00113-6 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Enomoto A, Takeda M, Tojo A, Sekine T, Cha SH, Khamdang S, Takayama F, Aoyama I, Nakamura S, Endou H, et al. Role of organic anion transporters in the tubular transport of indoxyl sulfate and the induction of its nephrotoxicity. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1711–1720. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000022017.96399.b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C, Gray NK, Floyd J, Palmer CN, Knott SA, Kolcic I, Polasek O, Graessler J, et al. SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout. Nat Genet. 2008;40:437–442. doi: 10.1038/ng.106. ng.106 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Enomoto A, Endou H. Roles of organic anion transporters (OATs) and a urate transporter (URAT1) in the pathophysiology of human disease. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2005;9:195–205. doi: 10.1007/s10157-005-0368-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wright AF, Rudan I, Hastie ND, Campbell H. A ‘complexity’ of urate transporters. Kidney Int. 2010;78:446–452. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.206. ki2010206 [pii] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]