Abstract

Testicular cancer is the most common cancer in men aged between 15 and 35 and more than 90% of testicular neoplasms are originated at germ cells. Recent research has shown the impact of microRNAs (miRNAs) in different types of cancer, including testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT). MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNAs which affect the development and progression of cancer cells by binding to mRNAs and regulating their expressions. The identification of functional miRNA-mRNA interactions in cancers, i.e. those that alter the expression of genes in cancer cells, can help delineate post-regulatory mechanisms and may lead to new treatments to control the progression of cancer. A number of sequence-based methods have been developed to predict miRNA-mRNA interactions based on the complementarity of sequences. While necessary, sequence complementarity is, however, not sufficient for presence of functional interactions. Alternative methods have thus been developed to refine the sequence-based interactions using concurrent expression profiles of miRNAs and mRNAs. This study aims to find functional cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions in TGCT. To this end, the sequence-based predicted interactions are first refined using an ensemble learning method, based on two well-known methods of learning miRNA-mRNA interactions, namely, TaLasso and GenMiR++. Additional functional analyses were then used to identify a subset of interactions to be most likely functional and specific to TGCT. The final list of 13 miRNA-mRNA interactions can be potential targets for identifying TGCT-specific interactions and future laboratory experiments to develop new therapies.

Keywords: miRNA-mRNA interaction, Testicular germ cell tumor, Gene ontology, KEGG pathways, Disease ontology

1 Introduction

Testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT) is the most common malignancy in males between 15 and 35, and comprises approximately 98% of all the testicular neoplasms. The American Cancer Society estimated that in 2015, ∼8430 new cases of TGCT would be diagnosed and ∼380 men would die from TGCT. Currently, about 1 of every 263 males develops testicular cancer at some point during their life. Confirmed risk factors of TGCT include family history, height (at adulthood), infertility and previous contralateral testicular cancer [1–3].

Apart from the contribution of these risk factors TGCT is strikingly heritable. Having a brother (father) diagnosed with TGCT results in an estimated 8 to 10 fold (4 to 6 fold) increased risk of TGCT for men. These numbers are significantly higher than the largest familial relative risk of adult cancers for first-degree relatives, which is estimated to 1.5 to 2.5 fold [1–3]. Various research groups have thus investigated the genetic risk factors of TGCT with the goal of identifying genes associated with TGCT [4–6]. In parallel, it has been discovered that microRNAs (miRNAs) can act as oncogenes or tumor suppressors by regulating the expression of genes in various types of cancers, including TGCT [7–9]. miRNAs have also been used to develop new therapies based on control of the expression levels of target genes by modifying the expression levels of their regulating miRNAs [10–13].

miRNAs regulate the expression levels of their target genes, which are identified by partial complementarity of binding sites. miRNA to mRNA binding results in cleavage of the target mRNA and inhibits the translation of mRNA to protein. Regulation by miRNA can thus be key to many biological processes and diseases, especially cancers. It has been estimated that 30% of all genes in human are regulated by miRNAs [14]. Investigating miRNAs and their relationships with mRNAs can thus help delineate underlying epigenetic regulations and disease mechanisms.

While partial complementarity is necessary for miRNA-mRNA interaction, only a small fraction of hundreds, or thousands of possible DNA sequence matches result in functional miRNA-mRNA interactions, where the miRNA expression levels change the mRNA transcript levels of target genes. This is because occurrence of functional interactions depends on additional binding factors. Moreover, only the smaller subset of bindings plays a role in tumor development and progression [15, 16]. Sequence-based predicted targets should thus be further filtered to identify more probable functional miRNA-mRNA interactions that are involved in cancer initiation and progression, or, are cancer- specific. Identifying such functional cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions in TGCT can shed light into novel mechanisms of TGCT initiation and progression and facilitate development of new therapies.

Various computational methods have been developed to refine sequence-based predicted interactions based on additional information, such as concurrent expression profiles of miRNAs and mRNAs on the same set of samples [17–21]. Correlation-based approaches, using, e.g., the Pearson or Spearman correlation between expression of miRNAs and mRNAs have been used to identify miRNA-mRNA interactions. Often only negative correlations are considered, following the general assumption that miRNAs repress the expression levels of mRNAs [17, 18]. A drawback of correlation coefficients is that they measure linear associations between two sets of observations (or their ranks) and are thus not suited for non-linear associations. Mutual Information (MI) can be alternatively used to identify associations between miRNAs and mRNAs. However, MI quantifies the common information between miRNA and mRNA expressions and is always non-negative. It thus fails to determine the direction of miRNA and mRNA effects [19].

Bayesian methods and regularized estimation procedures are two other classes of approaches for refining sequence-based interactions. Bayesian methods facilitate statistical inference by incorporating the prior knowledge into a probabilistic framework. GenMiR++ [20] is a well-known Bayesian model that scores each miRNA-mRNA pair to determine if the expression of miRNA explains the expression of target mRNA. Higher scores in this framework indicate interactions that are more likely to occur. miRNA-Target LASSO (TaLasso) [21] is, on the other hand, a popular regularized estimation approach for identifying miRNA-mRNA interactions. TaLasso is based on the Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) [22] and couples the LASSO's ℓ1 penalty with a non-positivity constraint.

In this paper, we propose a computational framework for identifying functional, cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions in TGCT. In the first step, we utilize miRNA and mRNA expression profiles to refine the sequence-based predicted interactions using a consensus-learning approach for discovering biological networks. More specifically, we consider consensus miRNA-mRNA interactions from TaLasso and GenMiR++. The rationale for considering these two estimation procedures is further discussed in Section 2. We then further screen out the identified interactions to find condition-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions, by considering interactions not identified in normal samples. Due to lack of normal testis samples, our validation step is based on normal samples from prostate tissues, which are expected to have close expression profiles to normal testis samples. The second step of our analysis entailed validation of identified interactions by investigating associations between genes in identified miRNA-mRNA interactions and known TGCT genes. To this end, we examine the enrichment of identified mRNAs from five perspectives: 1) gene functions by analyzing Gene Ontology (GO) terms, 2) disease association by analyzing Disease Ontology (DO) terms, 3) gene co-expression network, 4) physical interaction network, and 5) pathway enrichment analysis. Investigating the association between the identified genes and known TGCT genes helps identify potential targets of miRNAs in TGCT. We completed this step by examining the previous literature in search of evidence for the involvement of identified genes in TGCT.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, the data set used in the analysis and preprocessing steps are described. We also provide details on steps of the proposed framework to identify functional cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions, briefly described above. Section 3 contains the main results of the study. We conclude the paper with a discussion in Section 4.

2 Materials and Methods

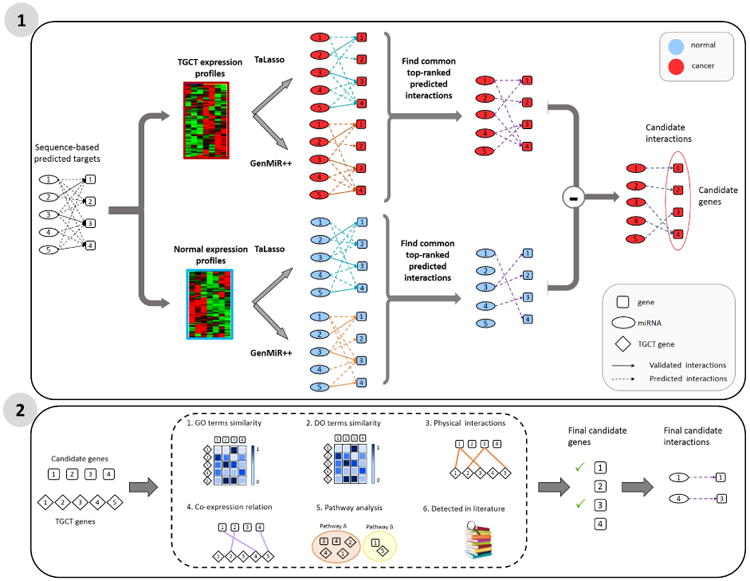

2.1 Overview of the Proposed Computational Framework

Figure 1 outlines the main steps of the proposed computational framework. As shown in the figure and briefly discussed in the Introduction, the framework consists of two main steps: 1) identifying functional cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions and 2) validating the identified interactions by associating the gene targets of miRNA-mRNA interactions to known TGCT genes from various perspectives.

Figure 1.

The proposed computational framework to identify functional cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions in TGCT. The first step includes refining the sequence-based predicted interactions using an ensemble learning approach based two existing approaches, namely, TaLasso and GenMiR++, as well as exclusion of interactions in normal samples. The second step includes investigating the association between gene targets of identified interactions from step 1 and known TGCT genes in different aspects of functionality e.g. GO/Do and pathway analyses.

In the first step, predicted sequence-based miRNA-mRNA are filtered to identify functional interactions by examining the miRNA and mRNA expression levels. To this end, we use a consensus-based approach by considering the intersection of miRNA-mRNA interactions from TaLasso and GenMiR++. GenMiR++ and TaLasso are two popular approaches that span two broad classes of approaches for reconstructing miRNA-mRNA interactions. GenMiR++ identifies interactions based on marginal associations between miRNA and mRNA expression levels; specifically GenMiR++ uses a Bayesian model to assess the significance of the the correlation between expression levels of pairs of miRNA and mRNA, without adjusting for other miRNA or mRNA levels. On the other hand, TaLasso utilizes a penalized regression framework to identify miRNA-mRNA interactions based on conditional associations; more specifically, it selects for large (negative) partial correlations between miRNA-mRNA after adjusting for the expression levels of other miRNA levels. [23] recently investigated advantages and shortcomings of network reconstruction methods based on marginal and conditional associations and found that consensus learning of interactions can improve the reliability of identified interactions. The underlying hypothesis in this step is that miRNA-mRNA interactions identified by both GenMiR++ and TaLasso are more likely functional.

Given the consensus miRNA-mRNA interactions, the algorithm then seeks to find cancer-specific interactions by filtering out interactions that are identified in normal samples. As pointed out in the Introduction, due to lack of normal samples from testis, in this paper we use publicly available normal prostate samples, which are expected to have similar expression profiles to normal testis samples. The second step of the algorithm consists of five different enrichment analyses to identify genes in functional cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions associated with known TGCT genes. Detailed description for each of the above steps, as well as data preprocessing procedures are presented in the remainder of this section.

2.2 Data Pre-processing

Matched miRNA and mRNA RNA-Seq files were downloaded in level 3.0 format for TGCT from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database1. RNA-Seq files in level 3.0 provide read_counts. Level 3.0 data from TCGA have been carefully pre-processed and checked for quality using various metrics, such as base quality per cycle and average coverage per human gene2. Thus, following [24], we did not perform any additional data pre-processing. However, prior to network analysis, we standardized the Read_counts in each sample, and applied log2-transformationon (read_counts + 1). The resulting data matrices for miRNA and mRNA were of dimensions [1046 × 156] and [20531 × 156], respectively; the first dimension in the above matrices shows the number of miRNAs and mRNAs, respectively, and the second dimension shows the number of common samples.

Normal prostate samples were downloaded from TCGA database in order to perform validation analysis and were similarly processed. The dimension of miRNA and mRNA matrices are [1046×52] and [20531×52], respectively. The miRNA and mRNA data from normal prostate tissue are based on identical platforms to TGCT, which justifies the use of the same preprocessing steps.

2.3 Refinement of Sequence-based Predicted Interactions

Sequence-based predicted interaction matrix was constructed based on putative interaction matrix available through the TaLasso homepage 3. The most recent validated interaction data were downloaded from miRWalk 2.0 4, and were used as the experimentally validated interaction matrix.

After collecting the required data, sequence-based intersections between genes and miRNAs were obtained. Then, miRNAs that did not target any mRNAs were removed from the data sets. Similarly, mRNAs that were not targeted by miRNAs were also removed. The number of the remaining miRNAs and mRNAs in TGCT and normal prostate tissues were 192 and 11339, respectively. TaLasso and GenMiR++ codes were run on the resulting preprocessed data to refine the sequence-based predicted interactions.

An enrichment analysis was then performed to assess the interactions identified using either method. This analysis determines the extent to which identified interactions corroborate with validated miRNA-mRNA interactions and consists of the following steps:

For n ∈ {100, 200,…, 1000}, select the top n ranked interactions and determine the number of experimentally validated interactions among them, denoted by p.

For i = 1,…, B, select n interactions randomly from all possible interactions and find the number of experimentally validated interactions among them; denote this number by pi, i = {1, 2,…, 100}.

Calculate the enrichment p-value as follows:

| (1) |

where I(.) is the indicator function.

B = 100 random samples was used in our analyses. The p-value from the enrichment analysis evaluates the significance of the result from each method. However, it should be noted that experimentally validated interactions may not be cancer-specific. Thus, while the p-values resulting from this analysis can be used to compare methods of learning functional miRNA-mRNA interactions, the results should be interpreted cautiously when assessing cancer-specific interactions.

To obtain cancer-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions, identified interactions using the proposed consensus approach were next screened for specificity to TGCT. In short, this is achieved by excluding miRNA-mRNA interactions that are also present in normal samples. As mentioned, due to unavailability of matched miRNA and mRNA data from normal testis samples, normal prostate samples were used in this paper. Prostate tissue was chosen because both testis and prostate are male-specific organs involved in reproduction. Thus, the normal testis and prostate tissues are expected to have similar epigenetics, including miRNA and mRNA expression profiles. In fact, previous research has identified a number of genes expressed in both tissues [25–34]. Normal prostate samples can thus be used in lieu of normal testis samples to identify cancer-specific interactions in TGCT. The process of identifying normal miRNA-mRNA interactions is similar to that of TGCT interactions; specifically, common interactions between top-ranked interactions predicted by TaLasso and GenMiR++ using data from normal prostate samples were obtained. The list of TGCT interactions were then contrasted with interactions in normal cells to exclude interactions present in both tissue types.

2.4 GO/DO Term Enrichment Analysis

An important post-genomic analysis is the study of functional relationship between genes. Relationships between genes can be analyzed from various perspectives and various types of relationships exists between genes.

The Gene Ontology (GO) consortium [35] aims to annotate consistent descriptions of gene products via the structured gene ontology. The ontology includes three main groups: cellular components, molecular function, and biological process. Cellular component terms determine the component of the cell where the gene product is expressed, such as “proteasome” and “ribosome”. Molecular function terms describe molecular-level activities of a gene product, such as “binding activity”. Biological process terms, on the other hand, include a series of events with a defined start point and end point such as “signal transduction”. Each group contains many terms with unique names and identifiers which have been organized into a directed acyclic graph (DAG). The hierarchy of nodes in this graph represents the generality of the terms, with terms higher in the hierarchy being more general. The edges of this graph represent various relationships between the GO term.

Similar to GO, Disease Ontology (DO) [36] provides a formal gene-disease association to bridge the gap between biological research and clinical applications as a post-genomic analysis. DO provides better understanding of disease states by placing heritable disorders in the context of other related diseases. Investigation of DO terms for genes thus helps delineate whether genes are likely to be associated with a specific disorder/disease. DO is also helpful in integrating disparate data through disease terminologies. Similar to GO, disease concepts in DO are organized as a DAG, such that the terms near to the root are more general terms and those farther away from the root are more specific.

To perform GO/DO term analysis, common GO/DO terms were sought between two lists of genes. To determine if the overlaps were statistically significant, enrichment analyses were performed for each common GO/DO term. In this regard, a list of genes equal to the number of query genes (13 genes, as described in Section 3) was randomly selected, from all genes included in human organism. Then, GO/DO terms were obtained for the list of randomly selected genes and p-value was calculated as

| (2) |

where T is the GO/DO term for which p-value is calculated for, and listi is the list of GO/DO terms for the ith randomly selected set of genes. Also, I(.) is the indicator function, which is 1 if T ∈ listi and 0 otherwise. The results in Section 3 are based on B = 100 random samples.

In this analysis we used the GOSemSim [37] and DOSE [38] R-packages to analyze GO and DO terms, respectively. GOSemSim measures functional similarities among genes based on GO terms based on a semantic comparison. DOSE similarly provides semantic similarity measurements of DO terms for gene products.

2.5 Co-expression and Physical Interaction Analysis

Biological interactions can be characterized in many ways. Two important notions are captured in physical interaction networks and gene co-expression networks (GCN). Physical interaction networks represent binding affinity of genes and their protein products, based on DNA sequences and protein. They thus provide insight into potential interactions that govern cellular functions. GCNs, on the other hand, capture similarities in activities of functions in a given biological condition. They thus provide valuable information functional similarities of genes, sharing of transcription factors, or membership in biological pathways [39, 40]. The complementary information about genetic interactions from these two networks can help predict biological functions of a given gene set and potential involvement in disease mechanisms.

We used GeneMANIA5 [41,42] to construct both physical and co-expression networks in TGCT samples. GeneMANIA utilizes information extracted from well-known databases such as Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)6, Pathway Common7, and BioGRID8. It can also add functionally related genes to a gene list, to provide a well-informed network.

2.6 Pathway Over-representation Analysis

Pathway analysis is another popular post-genomic approach, which helps investigate the combined effect of genes in a gene set or pathway. One of the earlier approaches for gene set analysis is over-representation analysis (ORA) [43]. Given a target set of genes T, ORA tests whether members of gene sets/pathways of interest are over-represented in the target list. To this end, ORA uses a counting strategy and calculates the probability of observing genes in a pathway by chance under the hypergeometric distribution. The p-value for each gene set/pathway P is thus calculated as

| (3) |

where N is the total number of genes in all the pathways, M is the number of genes in pathway P, K is the number of genes in the target set, and x is the number of genes present in both the target set T and the pathway of interest P.

ORA has a number of limitations and more advanced methods have been recently proposed for pathway enrichment analysis [44]. However, the hypergeometric test in ORA is particularly suitable in settings where the target set T is obtained from external information and is fixed, which is the case in our analysis. In particular, we perform ORA to identify biological pathways that are over-represented in the list of genes identified based on miRNA-mRNA interactions, as well as those over-represented in known TGCT genes. In this analysis, we assess the over-representation of known TGCT genes, as well as genes identified from miRNA-mRNA interactions in pathways from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes(KEGG). Here, P is a given KEGG pathway, and the target set T is either the set of known TGCT genes or genes from identified miRAN-mRNA interactions. A small p-value from (3) then indicates a smaller chance of overrepresentation of members of the KEGG pathway P in one of the target sets T. The KEGG pathways and their members were obtained using the R-package graphite [45].

3 Results

3.1 Refinement of Sequence-based Predicted Interactions

Figure 2(a) shows the number of common interactions between validated miRNA-mRNA interactions and the top n interactions identified by TaLasso and GenMiR++ for n ∈ {100, 200,…, 1000}. Enrichment analysis of the results for both methods and for all values of n ∈ {100, 200,…, 1000} results in small p-value (≤ 0.01), confirming that both methods are statistically more accurate than random guessing.

Figure 2.

(a) Number of validated interactions among top-ranked interactions; (b) Number of common interactions among top-ranked interactions between Talasso and GenMiR++.

The number of shared interactions between TaLasso and GenMiR++, as well as the number of validated interactions included in them are shown in Figure 2(b). It can be seen that, roughly, one-tenth of the number of top n predicted interactions are found using both estimation methods. Moreover, the growth rates of the curves corresponding to the number of shared interactions and the fraction of validated shared interactions are not the same. These results suggest that many of the shared interactions are not yet validated and there is a potential to identify new functional miRNA-mRNA interactions.

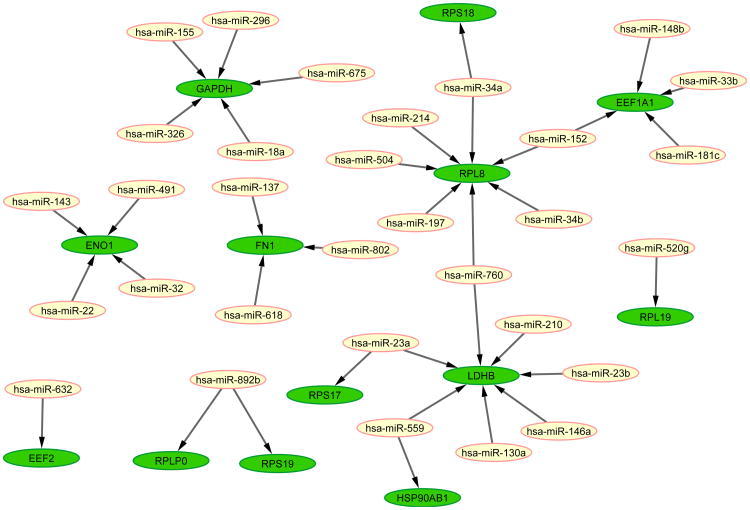

The results in Figure 2 suggest that for n ≤ 500 top ranked pathways, the number of validated interactions from TaLasso and GenMiR++ are the same. Of the top 500 interactions identified by both methods, 49 interactions are in common; 12 of these interactions are experimentally validated, and the remaining 37 interactions are novel9. Figure 3 shows the network of these 37 interactions, created using the Cytoscape platform [46]. The 37 identified interactions occur among 31 miRNAs and 13 genes, which we henceforth refer to as query genes. We limit our further analyses to these 37 interactions and 13 genes.

Figure 3.

The common interactions in top-ranked 500 interactions between TaLasso and GenMiR++. Green nodes represent mRNAs/genes and yellow nodes are miRNAs.

To validate these interactions, the same procedure was also run on normal prostate tissue samples from TGCA. In this set of samples, 52 interactions were common between the top 500 interactions from TaLasso and GenMiR++ interactions10. Interestingly, no common miRNA-mRNA interaction were found between TGCT and normal prostate samples. The interactions from normal prostate samples involve 7 genes, namely, EEF1A1, ACPP, KLK3, RDH11, SLC45A3, HSPA1A, and AZGP1. Only EEF1A1 is common between this list and our query genes. These results suggest that the identified miRNA-mRNA interactions are specific to TGCT.

It is believed that miRNAs do not play an independent role in cell processes, but act only through their target genes. Thus, to examine the relationship between the obtained interactions and TGCT we primarily focus on gene targets of identified TGCT interactions. To link our query genes to TGCT, we investigated known TGCT genes with proven association with the disease. Using two databases that describe the association between genes and diseases, namely, Disease and Genes Annotations (DGA)11 and MalaCards12, we identified 13 genes that have been declared to be associated with TGCT in both databases13. Table 1 lists TGCT and query genes.

Table 1.

TGCT and query genes. The first nine TGCT genes are from DGA database and remains are from MalaCards database.

| TGCT Genes | Query Genes |

|---|---|

| ATF7IP | GAPDH |

| DMRT1 | ENO1 |

| ESR1 | EEF2 |

| ESR2 | RPL8 |

| KITLG | LDHB |

| LHCGR | EEF1A1 |

| POLG | FN1 |

| TERT | RPS17 |

| BCL10 | RPS18 |

| KIT | RPS19 |

| STK10 | RPLP0 |

| STK11 | RPL19 |

| FGFR3 | HSP90AB1 |

3.2 GO/DO Term Enrichment Analysis

Figure 4(a) shows the common GO terms between our query and known TGCT genes, along with the name of the GO terms and their corresponding p-values. Only 5 GO terms were significantly enriched for both sets with a p-value < 0.01 using the permutation test in (2). We next measured the similarity between our query genes and those related to TGCT based on their common GO terms using the method of Wang [47], which is implemented in the GOSemSim R-package. Wang's method calculates the similarity between two GO terms by considering their location in the GO graph and their relationships with their ancestors. The resulting similarity matrix is depicted in Figure 4(b).

Figure 4.

(a) The network illustrates the shared GO terms between query genes and TGCT genes. Yellow nodes are GO terms, green nodes are TGCT genes, and blue nodes are query genes. The name of GO terms are in the below of the network. The numbers in parenthesis show their p-values. (b) GO term similarity between TGCT genes and query genes. TGCT genes and query genes are in rows and in columns, respectively.

In addition to GO terms, the common DO terms between the two lists of genes were also investigated. Similar to the GO term analysis, the association of DO terms were assessed using the permutation test in (2). However, two query genes and one TGCT gene were not included in the DO database and were hence removed from the analysis. Figure 5(a) shows the common DO IDs along with their names and corresponding p-values. The similarity matrix of DO terms is depicted in Figure 5(b).

Figure 5.

(a) The network illustrates the shared DO terms between query genes and TGCT genes. Yellow nodes are DO terms, green nodes are TGCT genes, and blue nodes are query genes. The name of DO IDs are provided in the below of the network. The numbers in parenthesis show their p-values. (b) DO term similarity between TGCT genes and query genes. TGCT genes are in rows and query genes are in columns.

Table 2 summarizes the findings of GO and DO analyses in Figures 4 and 5. The figure shows the query and TGCT genes mapped to enriched GO/DO terms. The genes included are those mapped to significantly enriched GO/DO terms (p-value < 0.01), but have been filtered to only include genes from either TGCT or query genes with relatively large similarity (> 0.4) with members of the other set.

Table 2.

Significant GO/DO terms.

| GO/DO Term | Query Genes | TGCT Genes | Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0002020 | FN1 | POLG, BCL10 | [0.6-0.8] |

| GO:0017134 | RPS19 | FGFR3 | [0.6-0.8] |

| GO:0019900 | HSP90AB1 | BCL10 | [0.6-0.8] |

| GO:0000049 | EEF1A1 | TERT | [0.4-0.6] |

| GO:0030235 | HSP90AB1 | ESR1 | [0.4-0.6] |

| DOID:3275 | GAPDH | ESR1 | [0.4-0.6] |

| DOID:1168, DOID:5082, DOID:1936 | FN1 | ESR1, ESR2, TERT | [0.4-0.6] |

The joint mapping of TGCT and query genes to GO/DO terms highlight common functionality of the query genes with known TGCT genes. For instance, GO:0017134 is believed to “interact with a fibroblast growth factor” [35]. Fibroblast Growth Factors (FGFs) are known as hormonal factors and play a key role in regulating growth and development of several reproductive organs, including the testis [48]. Similarly, GO:0030235 is related to the activity of nitric oxide synthase. Nitric Oxide (NO) is a reactive radical gas mediating many biological functions. Of the different forms of Nitric Oxide Synthase (NOS) the endothelial form (eNOS) has a role in modulating sexual and reproductive function. It has also been suggested that NO might be involved in different testicular abnormalities, i.e. in inhibiting human sperm motility, in germ cell degeneration and in stress-impaired testicular steroidogenesis [49–51]. Finally, GO:0019900 is known to “interact with kinases, i.e., enzymes that catalyze the transfer of a phosphate group.” The protein kinase gene family is the most frequently mutated in human cancer and the role of mutated protein kinases in development of TGCT has been previously reported [52]. Of the reported DO terms, DOID:1168, or familial hyperlipidemia, is an inherited disorder that causes high cholesterol and high levels of triglycerides in the blood; previous studies have shown a relationship between male fertility and hyperlipidemia [53, 54].

3.3 Co-expression and Physical Interaction Analysis

Figure 6(a) shows the gene co-expression network for query and TGCT genes. One of the TGCT genes, FGFR3, is absent in the network due to the unavailability of co-expression information about it in GeneMANIA. Interestingly, about 50% of the query genes have direct co-expression relationship with known TGCT genes. Figure 6(b) shows the physical interaction network between query and TGCT genes. Only 8 of 13 TGCT genes have known physical interactions in the GeneMANIA database; the 5 TGCT genes with no physical interactions are excluded from the network.

Figure 6.

Networks of genes with direct co-expression (a) or physical (b) interactions with the query genes or TGCT genes. In both networks, green nodes represent known TGCT genes, blue nodes represent query genes, and yellow nodes are genes with direct interactions with the former two groups based on information from GeneMANIA. The orange edges in this figure show direct relationships between query genes and TGCT genes.

The observations from co-expression and direct physical interactions are summarized in Table 3. It can be seen that all query genes, except LDHB and FN1, have direct physical interactions with at least one of the Estrogen Receptor (ESR) genes, ESR1 and ESR2. Among the query genes, RPL8 and HSP90AB1 have the highest number of direct interactions in the physical interaction network. On the other hand, LDHB and FN1 have the highest number of direct relationships in GCN. However, these genes do not have any direct physical relationship with TGCT genes.

Table 3.

Direct relationships between Query and TGCT genes in GCN and physical interaction network.

| Query Genes | TGCT genes with direct co-expression relation | TGCT genes with direct physical interaction |

|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | - | ESR1 |

| ENO1 | - | ESR1, TERT |

| EEF2 | STK11, KIT | ESR1 |

| LDHB | KIT, POLG, BCL10 | - |

| EEF1A1 | ESR2 | ESR1 |

| FN1 | LHCGR, TERT | - |

| RPS17 | - | ESR1 |

| RPS18 | ESR2 | ESR1, ESR2 |

| RPS19 | - | ESR1 |

| RPLP0 | - | ESR1, ESR2 |

| RPL8 | TERT | ESR1, FGFR3, ATF7IP |

| RPL19 | KITLG | ESR1 |

| HSP90AB1 | - | ESR1, FGFR3, STK11 |

3.4 Pathway Over-representation Analysis

Pathway analysis was performed using the ORA method, and p-values were separately calculated for each KEGG pathway based on query and TGCT genes14 [55]. 28 and 32 pathways out of 295 KEGG pathways have common genes with query and TGCT genes, respectively and they are all significantly enriched (p-value < 0.01). Further, 6 KEGG pathways are common between query and TGCT genes15. Figure 7 summarizes these results.

Figure 7.

Pathway over-representational analysis. (a) Bar chart of common pathways which query and TGCT genes hit them. Blue and green bars correspond to query genes and to TGCT genes, respectively. Each bar shows the number of genes which are included in the pathway. Label of bars show the obtained p-value based on Eq. 3; (b) The name of each pathway and genes which are included in it.

Aside from “pathways in cancer”, which is a general pathway, direct impacts of “PI3K-AKT signaling pathway”, “Proteoglycans in cancer” and “Estrogen signaling pathway” on testicular have been previously reported [56–58]. Given that PI3K-AKT pathway is dysregulated in several cancers and has a cross talk with WNT-CTNNB1 signaling pathway, Boyer et al. [56] have shown the involvement and synergy of the PI3K-AKT and WNT-CTNNB1 pathways in the formation of sex cord tumors of the testis. The role of proteoglycans in various cancer processes, such as proliferation and metastasis, has also been observed. Furthermore, it has been observed that proteoglycans such as glypican (-1, -3) may interact with growth factors, cytokines, morphogens and enzymes, also leading to tumor growth and invasion. In [57], expression of glypican-3 (GPC3) has been observed in all samples of neoplastic cells of yolk-sac tumor. According to [58] estrogens, the archetype of female hormones, contribute to control of male germ cell proliferation and hypofertility. The authors have also shown that estrogens contributed to human testicular germ cell cancer proliferation by rapid activation of ERK1/2 and PKA through a membrane nonclassical ER.

Moreover, actin cytoskeleton has been shown to have a role in cancer cell migration and invasion [59]. Finally, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) in “AMPK signaling pathway”, can act as a physiological cellular energy sensor and strongly suppresses cell proliferation in both nonmalignant and tumor cells [60].

3.5 Towards Finding Effective miRNA-mRNA Interactions

Investigation of existing literature reveals that five of the query genes, namely, HSP90AB1, EEF1A1, LDHB, FN1, and RPS19 have been associated with spermatogenesis, TGCT, yolk sac tumors16, and seminomas17. Interestingly, these genes, except for LDHB, are involved in enriched pathways and/or common significant GO terms with TGCT genes. It emphasizes on the power of the performed computational analyses. In the following, we briefly discuss the evidence supporting each of these genes.

HSP90AB1 and EEF1A1 play key roles in regulation of spermatogenesis [61]. Our analysis finds that HSP90AB1 is involved in three enriched pathways that also include known TGCT genes; it has a common significant GO term with BCL10 and ESR1, has three direct physical interactions with ESR1, STK11, and FGFR3. EEF1A1, on the other hand, is included in common significant GO term with TERT; it also directly interacts with ESR1 and ESR2 in GCN and physical interaction networks.

LDHB is over-expresssed in TGCT and FN1 is differentially expressed in yolk sac tumors [62, 63]. Based on our analysis, LDHB has direct interactions with known TGCT genes in GCN. FN1, on the other hand, is involved in four enriched pathways and a common significant GO term with known TGCT genes; it also has direct relationships in GCN with TGCT known genes.

RPS19 is a ribosomal protein and has been recently found to be associated with sex development [64]. Specifically, overexpression of RPS19 has been detected in seminoma in comparison with normal testicular samples [65]. Interestingly, there is a difference between RPS19 and other query genes whose names start with ‘RP’. None of the other “RP” genes are involved in any enriched pathways and all of them have direct physical interaction with estrogen genes, except for RPS19 which has a common significant GO term, GO:0017134 with FGFR3, one of the TGCT genes. GO:0017134 concerns ‘fibroblast growth factor (FGF) binding’; FGFs are a family of growth factors, which play important roles in the processes of differentiation and proliferation of different tissues. The relationship between FGFs and testis has already been observed in [66].

Finally, EEF2 is involved in an enriched pathway, “AMPK signaling pathway”, with STK11. It also has direct interaction with STK11 and KIT in GCN and direct physical interaction with ESR1. EEF2 has been found to be over-expressed as an antigene in various cancers [67]; however, it has not yet been associated with TGCT or related diseases.

No strong evidence was found in support of the other query genes based on a review of the literature or in this study. Thus, while these genes represent good potential for future research on TGCT, we henceforth focus on the genes described above, namely HSP90AB1, EEF1A1, LDHB, FN1, EEF2, and RPS19, as potential targets of miRNAs in TGCT. Figure 8 shows the identified miRNA-mRNA interactions for the above genes; it contains 17 interactions involving 16 different miRNAs.

Figure 8.

The final inferred miRNA-mRNA interaction network after removing genes not found to be strongly related to TGCT using the functional analyses of Sections 3.2-3.4. Orange nodes show miRNAs with zero expression values in testis and sperm tissues, based on the data from miRmine.

To further delineate the effect of miRNAs on TGCT, we used the expression data for miRNAs in testis and sperm tissues from the miRmine18 database. Table 4 shows the expression values of miRNAs in log2 value of Reads Per Million (RPM); data on both 3p and 5p strands were available for some miRNAs, and have been reported. The data suggest that hsa-miR-137, hsa-miR-559, and hsa-miR-802 are not expressed in testis or sperm tissues, and can be excluded from further considerations. The above three miRNAs have been marked with an orange color in the network of TGCT-specific miRNA-mRNA interactions in Figure 8.

Table 4.

Expression of miRNAs in testis and sperm. The unit of values is log2(RPM).

| miRNAs | Testis | Sperm |

|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-130a-5p | 0 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-130a-3p | 9.2 | 7.1 |

| hsa-miR-137 | 0 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-146a-5p | 9.8 | 13.4 |

| hsa-miR-146a-3p | 0 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-148b-5p | 4.2 | 6.1 |

| hsa-miR-148b-3p | 10.2 | 11.2 |

| hsa-miR-152-5p | 4.8 | 2.1 |

| hsa-miR-152-3p | 11.6 | 11.2 |

| hsa-miR-181c-5p | 7.3 | 7.7 |

| hsa-miR-181c-3p | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| hsa-miR-210-5p | 1.4 | 0.7 |

| hsa-miR-210-3p | 6.4 | 8.4 |

| hsa-miR-23a-5p | 0 | 1.1 |

| hsa-miR-23a-3p | 12.6 | 11.3 |

| hsa-miR-23b-5p | 3.8 | 3 |

| hsa-miR-23b-3p | 12.7 | 10.1 |

| hsa-miR-33b-5p | 0 | 3.8 |

| hsa-miR-33b-3p | 2 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-559 | 0 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-618 | 3.5 | 3.6 |

| hsa-miR-632 | 1 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-760 | 5.8 | 6 |

| hsa-miR-802 | 0 | 0 |

| hsa-miR-892b | 5.8 | 7.3 |

A number of identified miRNAs have been previously found to be associated with TGCT. Specifically,

hsa-miR-892b is member of miR-888 gene family that has restricted expression in adult testicular germ cells. They are known as Cancer-testis (CT) antigens which are clustered near the end of the long arm of the X chromosome (Xq27-Xq28) and contain several reported miRNAs like hsa-miR-888, hsa-miR-890, hsa-miR-891a, hsa-miR-891b, hsa-miR-892a, and hsa-miR-892b [68–70];

hsa-miR23a and hsa-miR-23b are involved in epididymal maturation of sperm and express in epididymides [71];

hsa-miR-33*—including both hsa-miR-33a and hsa-miR-33b—has been shown to be differentially expressed in testes [72]; moreover, according to [73] hsa-miR-33a-5p directly targets EEF1A1;

hsa-miR-148a and hsa-miR-148b have been found to affect the modification of susceptibility to oligozoospermia [74];

by comparing fertile and infertile populations of men hsa-miR-152-3p has been found to be correlated with sperm concentration [75];

miR-181b and miR-181c were found up-regulated in adult in mouse testis tissue [76], and are involved in transcriptional regulation in haploid germ cells by targeting rsbn1, a gene postulated to be involved in transcriptional regulation in haploid germ cells;

miR-155 and miR-146a have been found to be present in male serum [77] and to be correlated with each other; however, while miR-155 is associated with male sub-fertility independent of Low-Grade Systemic Inflammation (LGSI) or androgens, miR-146a is only weakly associated with sub-fertility and LGSI;

by comparing miRNA expression patterns for abnormal semen from infertile males and normal semen from healthy males, hsa-miR-130a has been found to be significantly under-expressed in the abnormal semen compared with the normal semen [78].

4 Discussion

miRNAs play key roles in many complex diseases, including various cancers. Identification of miRNAs involved in a disease, such as TGCT, can facilitate the development of new therapies to control and treat the disease by designing Anti-miRNA Oligonucleotides (AMOs). AMOs are synthetically designed molecules to neutralize miRNA function in cells in order to achieve the desired response. In cases where over/under expression of miRNAs leads to disease initiation or progression, AMOs can thus be used to develop therapies by controlling regulation of miRNAs [10–13,79,80]. As an example, miR-21 is known as an oncomir in several cancers. Si et al. [79] and Sicard et al. [80] have successfully used anti-miR-21 to control tumor growth in breast and pancreatic cancer, respectively. Further biological investigations to assess the therapeutic potential of miRNAs identified in this study and designing AMOs to control functional miRNAs can thus lead to future discoveries.

Despite the promise of miRNAs as potential therapeutic targets, the identification of functional disease-specific miRNAs is challenging. The primary approach is to first find genes that are associated with the diseases, and then find miRNAs that target these genes, i.e., miRNA-mRNA interactions. Finding such interactions in the laboratory is a time and cost consuming process. Hence, prior to conducting laboratory experiments, it is often preferred to predict and identify more likely functional interactions using computational methods and narrow down the primitive list of possible interactions. Such an approach can reduce the number of possible interactions to a few candidate interactions, resulting in more efficient and amenable experiments. In this study, we employed such a strategy in the setting of TGCT and developed a computational framework to narrow down the potential list of functional miRNA-mRNA interactions in TGCT to a small set of 13 interactions. This list can provide an ideal candidate miRNAs for in vivo validation experiments and designing AMOs to control the activity of miRNAs and their target genes.

A potential limitation of our analysis is the use of normal prostate samples for validation of TGCT-specific interactions, due to unavailability of matched miRNA and mRNA expression profiles from normal testis samples. While the similarity of gene expression profiles in normal prostate and testis samples justifies our analysis, improved results may be obtained if the method is used with expression profiles from cancer and normal testis tissue.

While the current study focused on TGCT, the proposed approach can be similarly applied to other diseases, including cancers. The availability of an automated pipeline can thus facilitate future research on the role of miRNAs in complex diseases.

Few possible extensions can improve the performance and reliability of the proposed framework. First, in the proposed framework, the primary list of interactions were identified using an ensemble learning approach, by applying two existing method of interaction prediction based on expression profiles to filter sequence-based predicted interactions. Ensemble methods can generate more accurate and reliable results than their individual building blocks and are hence preferable [81, 82]. It may thus be fruitful to include additional miRNA-mRNA interaction learning methods in the proposed ensemble learning approach. Moreover, in the proposed framework, candidate interactions are primarily narrowed down by filtering the genes, and information from miRNAs is only incorporated at the last step. As new miRNA expression repositories and knowledge bases emerge, it may be beneficial to incorporate the existing miRNA expression profiles and annotations in earlier steps of the framework.

Supplementary Material

Supp. 1: The list of top-ranked 500 interactions using TaLasso and GenMiR++ in TGCT.

Supp. 2: The list of common interactions among top-ranked 500 interactions between TaLasso and GenMiR++ in TGCT.

Supp. 3: The list of common interactions among top-ranked 500 interactions between TaLasso and GenMiR++ in prostate.

Supp. 4: List of pathways and involved genes.

Supp. 5: List of pathways and p-values.

Supp. 6: mRNA and miRNA data files as ‘*.RData’.

Supp. 7: A short note on the required preprocessing steps of level 3.0 TCGA data.

Code for reproducing results of experiments at GitHub repository, ‘FCS-miRNA-mRNA-Net’19.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editor, the associate editor and the anonymous referees for helpful comments that led to improvements in the manuscript. Ali Shojaie would also like to acknowledge the support from the U.S. National Science Foundation (grant DMS-1161565).

Footnotes

For more information visit https://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/tcgaDataType.jsp.

The list of interactions is available in Supp. 1 and 2.

The list of interactions is available in Supp. 3.

The TGCT genes in DGA correspond to the id DOID:5557, “testicular germ cell cancer”, and TGCT genes in MalaCards correspond to “testicular germ cell tumor” disease.

The list of pathways and their involved genes is available in Supp. 4.

The list of pathways and their p-values is available in Supp. 5.

Yolk sac tumor is a kind of germ cell tumor cancers.

Testicular seminomas are the most common testicular tumors and account for approximately 45% of all primary testicular tumors.

http://guanlab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/mirmine, released July 2015.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Testicular cancer. American Cancer Society. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reuter Victor E. Origins and molecular biology of testicular germ cell tumors. Modern Pathology. 2005;18:S51–S60. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMaster Mary L, Heimdal Ketil R, Loud Jennifer T, Bracci Janet S, Rosenberg Philip S, Greene Mark H. Nontesticular cancers in relatives of testicular germ cell tumor (TGCT) patients from multiple-case tgct families. Cancer medicine. 2015 doi: 10.1002/cam4.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rapley Elizabeth A, Crockford Gillian P, Teare Dawn, Biggs Patrick, Seal Sheila, Barfoot Rita, Edwards Sandra, Hamoudi Rifat, Heimdal Ketil, Fosså Sophie D, et al. Localization to Xq27 of a susceptibility gene for testicular germ-cell tumours. Nature Genetics. 2000;24(2):197–200. doi: 10.1038/72877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Turnbull Clare, Rapley Elizabeth A, Seal Sheila, Pernet David, Renwick Anthony, Hughes Deborah, Ricketts Michelle, Linger Rachel, Nsengimana Jeremie, Deloukas Panagiotis, et al. Variants near DMRT1, TERT and ATF7IP are associated with testicular germ cell cancer. Nature Genetics. 2010;42(7):604–607. doi: 10.1038/ng.607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Looijenga Leendert HJ, Stoop Hans, Biermann Katharina. Testicular cancer: biology and biomarkers. Virchows Archiv. 2014;464(3):301–313. doi: 10.1007/s00428-013-1522-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croce Carlo M, Calin George A. miRNAs, cancer, and stem cell division. Cell. 2005;122(1):6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iorio Marilena V, Ferracin Manuela, Liu Chang-Gong, Veronese Angelo, Spizzo Riccardo, Sabbioni Silvia, Magri Eros, Pedriali Massimo, Fabbri Muller, Campiglio Manuela, et al. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2005;65(16):7065–7070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calin George Adrian, Croce Carlo Maria. MicroRNA-cancer connection: the beginning of a new tale. Cancer Research. 2006;66(15):7390–7394. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thorsen Stine B, Obad Susanna, Jensen Niels F, Stenvang Jan, Kauppinen Sakari. The therapeutic potential of microRNAs in cancer. The Cancer Journal. 2012;18(3):275–284. doi: 10.1097/PPO.0b013e318258b5d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinther Jeppe, Rukov Jakob Lewin, Shomron Noam. From Nucleic Acids Sequences to Molecular Medicine. Springer; 2012. MicroRNAs and their antagonists as novel therapeutics; pp. 503–523. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rooij Eva van, Kauppinen Sakari. Development of microRNA therapeutics is coming of age. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2014;6(7):851–864. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201100899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stenvang Jan, Petri Andreas, Lindow Morten, Obad Susanna, Kauppinen Sakari. Inhibition of microRNA function by antimiR oligonucleotides. Silence. 2012;3(1):1. doi: 10.1186/1758-907X-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garzon Ramiro, Marcucci Guido, Croce Carlo M. Targeting microRNAs in cancer: rationale, strategies and challenges. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2010;9(10):775–789. doi: 10.1038/nrd3179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartel David P. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobsen Anders, Wen Jiayu, Marks Debora S, Krogh Anders. Signatures of RNA binding proteins globally coupled to effective microRNA target sites. Genome Research. 2010;20(8):1010–1019. doi: 10.1101/gr.103259.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van der Auwera Ilse, Limame R, Van Dam P, Vermeulen PB, Dirix LY, Van Laere SJ. Integrated miRNA and mRNA expression profiling of the inflammatory breast cancer subtype. British Journal of Cancer. 2010;103(4):532–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Huiqing, Brannon Angela R, Reddy Anupama R, Alexe Gabriela, Seiler Michael W, Arreola Alexandra, Oza Jay H, Yao Ming, Juan David, Liou Louis S, et al. Identifying mRNA targets of microRNA dysregulated in cancer: with application to clear cell renal cell carcinoma. BMC Systems Biology. 2010;4(1):51. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sales Gabriele, Coppe Alessandro, Bisognin Andrea, Biasiolo Marta, Bortoluzzi Stefania, Romualdi Chiara. MAGIA, a web-based tool for miRNA and genes integrated analysis. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38(Suppl 2):W352–W359. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang Jim C, Morris Quaid D, Frey Brendan J. Bayesian inference of microRNA targets from sequence and expression data. Journal of Computational Biology. 2007;14(5):550–563. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2007.R002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muniategui Ander, Nogales-Cadenas Rubén, Vázquez Miguél, Aranguren Xabier L, Agirre Xabier, Luttun Aernout, Prosper Felipe, Pascual-Montano Alberto, Rubio Angel. Quantification of miRNA-mRNA interactions. PloS One. 2012;7(2):e30766–e30766. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tibshirani Robert. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1996:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sedaghat Nafiseh, Saegusa Takumi, Randolph Timothy, Shojaie Ali. Comparative study of computational methods for reconstructing genetic networks of cancer-related pathways. Cancer Informatics. 2014;13(Suppl 2):55. doi: 10.4137/CIN.S13781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobsen Anders, Silber Joachim, Harinath Girish, Huse Jason T, Schultz Nikolaus, Sander Chris. Analysis of microRNA-target interactions across diverse cancer types. Nature structural & molecular biology. 2013;20(11):1325–1332. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghafouri-Fard Soudeh, Ousati Ashtiani Zahra, Sabah Golian Bareto, Hasheminasab Seyyed-Mohammad, Modarressi Mohammad Hossein. Expression of two testis-specific genes, SPATA19 and LEMD1, in prostate cancer. Archives of Medical Research. 2010;41(3):195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Riggin Andrew John, Siddiqui Mohummad Minhaj. Development of intermediate and high-risk prostate cancer after testicular cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology (Meeting Abstracts) 2015;33(7) 177 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aydogmus Yasin, Kilinc Muhammet Fatih, Kabar Mucahit, Ozer Elif, Resorlu Berkan. Metastasis of prostate adenocarcinoma to the testis. Urology. 2015;86(1):206. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2015.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Møller Henrik. Trends in incidence of testicular cancer and prostate cancer in denmark. Human Reproduction. 2001;16(5):1007–1011. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.5.1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar Senthil R, Bryan Jeffrey, Esebua Magda. Epigenetic changes in testis specific Y-like 5 gene in human prostate carcinoma: Gene expression analysis and its potential as a biomarker. Cancer Research. 2014;74(19 Supplement):398–398. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bera Tapan K, Maitra Rangan, Iavarone Carlo, Salvatore Giuliana, Kumar Vasantha, Vincent James J, Sathyanarayana BK, Duray Paul, Lee BK, Pastan Ira. PATE, a gene expressed in prostate cancer, normal prostate, and testis, identified by a functional genomic approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99(5):3058–3063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052713699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bera Tapan Kumar, Hahn Yoonsoo, Lee Byungkook, Pastan Ira H. TEPP, a new gene specifically expressed in testis, prostate, and placenta and well conserved in chordates. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;312(4):1209–1215. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margalit M, Yogev L, Yavetz H, Lehavi O, Hauser R, Botchan A, Barda S, Levitin F, Weiss M, Pastan I, et al. Involvement of the prostate and testis expression (PATE)-like proteins in sperm–oocyte interaction. Human Reproduction. 2012:des064. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lau Yun-Fai Chris, Zhang Jianqing. Expression analysis of thirty one Y chromosome genes in human prostate cancer. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2000;27(4):308–321. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2744(200004)27:4<308::aid-mc9>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dasari Vijay K, Goharderakhshan Reza Z, Perinchery Geetha, Li Long-Cheng, Tanaka Yuichiro, Alonzo Judy, Dahiya Rajvir. Expression analysis of Y chromosome genes in human prostate cancer. The Journal of Urology. 2001;165(4):1335–1341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gene Ontology Consortium et al. The gene ontology project in 2008. Nucleic Acids Research. 2008;36(suppl 1):D440–D444. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schriml Lynn Marie, Arze Cesar, Nadendla Suvarna, Chang Yu-Wei Wayne, Mazaitis Mark, Felix Victor, Feng Gang, Kibbe Warren Alden. Disease Ontology: a backbone for disease semantic integration. Nucleic Acids Research. 2012;40(D1):D940–D946. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu Guangchuang, Li Fei, Qin Yide, Bo Xiaochen, Wu Yibo, Wang Shengqi. GOSemSim: an R package for measuring semantic similarity among GO terms and gene products. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(7):976–978. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu Guangchuang, Wang Li-Gen, Yan Guang-Rong, He Qing-Yu. DOSE: an R/Bioconductor package for disease ontology semantic and enrichment analysis. Bioinformatics. 2014:btu684. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weirauch Matthew T. Gene coexpression networks for the analysis of DNA microarray data. Applied Statistics for Network Biology: Methods in Systems Biology. 2011:215–250. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roy Swarup, Bhattacharyya Dhruba K, Kalita Jugal K. Reconstruction of gene co-expression network from microarray data using local expression patterns. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15(Suppl 7):S10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-S7-S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warde-Farley David, Donaldson Sylva L, Comes Ovi, Zuberi Khalid, Badrawi Rashad, Chao Pauline, Franz Max, Grouios Chris, Kazi Farzana, Lopes Christian Tannus, et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Research. 2010;38(suppl 2):W214–W220. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Montojo Jason, Zuberi Khalid, Rodriguez Harold, Bader Gary D, Morris Quaid. GeneMANIA: fast gene network construction and function prediction for Cytoscape. F1000Research. 2014;3 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.4572.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Draghici Sorin, Khatri Purvesh, Tarca Adi Laurentiu, Amin Kashyap, Done Arina, Voichita Calin, Georgescu Constantin, Romero Roberto. A systems biology approach for pathway level analysis. Genome Research. 2007;17(10):1537–1545. doi: 10.1101/gr.6202607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khatri Purvesh, Sirota Marina, Butte Atul J. Ten years of pathway analysis: current approaches and outstanding challenges. PLoS Computational Biology. 2012;8(2):e1002375. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sales Gabriele, Calura Enrica, Romualdi Chiara. graphite: GRAPH Interaction from pathway Topological Environment. R package version 1.16.0 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shannon Paul, Markiel Andrew, Ozier Owen, Baliga Nitin S, Wang Jonathan T, Ramage Daniel, Amin Nada, Schwikowski Benno, Ideker Trey. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang James Z, Du Zhidian, Payattakool Rapeeporn, Yu Philip S, Chen Chin-Fu. A new method to measure the semantic similarity of GO terms. Bioinformatics. 2007;23(10):1274–1281. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang Xin, Skibba Melissa, Zhang Chi, Tan Yi, Xin Ying, Qu Yaqin. The roles of fibroblast growth factors in the testicular development and tumor. Journal of Diabetes Research. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/489095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weinberg JB, Doty E, Bonaventura J, Haney AF. Nitric oxide inhibition of human sperm motility. Fertility and Sterility. 1995;64(2):408–413. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santoro G, Romeo C, Impellizzeri P, Ientile R, Cutroneo G, Trimarchi F, Pedale S, Turiaco N, Gentile C. Nitric oxide synthase patterns in normal and varicocele testis in adolescents. BJU International. 2001;88(9):967–973. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-4096.2001.02446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Defoor William R, Kuan Chia-Yi, Pinkerton Malinda, Sheldon Curtis A, Lewis Alfor G. Modulation of germ cell apoptosis with a nitric oxide synthase inhibitor in a murine model of congenital cryptorchidism. The Journal of Urology. 2004;172(4):1731–1735. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000138846.56399.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bignell Graham, Smith Raffaella, Hunter Chris, Stephens Philip, Davies Helen, Greenman Chris, Teague Jon, Butler Adam, Edkins Sarah, Stevens Claire, et al. Sequence analysis of the protein kinase gene family in human testicular germ-cell tumors of adolescents and adults. Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer. 2006;45(1):42–46. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samir Bashandy AE. Effect of fixed oil of Nigella sativa on male fertility in normal and hyperlipidemic rats. International Journal of Pharmacology. 2007;3(1):27–33. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bataineh Hameed N, Nusier Mohamad K. Effect of cholesterol diet on reproductive function in male albino rats. Saudi Medical Journal. 2005;26(3):398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kanehisa Minoru, Goto Susumu. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Boyer Alexandre, Paquet Marilène, Laguë Marie-Noëlle, Hermo Louis, Boerboom Derek. Dysregulation of WNT/CTNNB1 and PI3K/AKT signaling in testicular stromal cells causes granulosa cell tumor of the testis. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30(5):869–878. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ota Satoshi, Hishinuma Michiyo, Yamauchi Naoko, Goto Akiteru, Morikawa Teppei, Fujimura Tetsuya, Kitamura Tadaichi, Kodama Tatsuhiko, Aburatani Hiroyuki, Fukayama Masashi. Oncofetal protein glypican-3 in testicular germ-cell tumor. Virchows Archiv. 2006;449(3):308–314. doi: 10.1007/s00428-006-0238-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bouskine Adil, Nebout Marielle, Mograbi Baharia, Brucker-Davis Francoise, Roger Cyril, Fenichel Patrick. Estrogens promote human testicular germ cell cancer through a membrane-mediated activation of extracellular regulated kinase and protein kinase A. Endocrinology. 2008;149(2):565–573. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yamaguchi Hideki, Condeelis John. Regulation of the actin cytoskeleton in cancer cell migration and invasion. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research. 2007;1773(5):642–652. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim Hyeong-Jin, Kim Sang-Ki, Kim Byeong-Soo, Lee Seung-Ho, Park Young-Seok, Park Byung-Kwon, Kim So-Jung, Kim Jin, Choi Changsun, Kim Jong-Suk, et al. Apoptotic effect of quercetin on HT-29 colon cancer cells via the AMPK signaling pathway. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(15):8643–8650. doi: 10.1021/jf101510z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tash Joseph S, Chakrasali Ramappa, Jakkaraj Sudhakar R, Hughes Jennifer, Kendall Smith S, Hornbaker Kaori, Heckert Leslie L, Ozturk Sedide B, Kyle Hadden M, Kinzy Terri Goss, et al. Gamendazole, an orally active indazole carboxylic acid male contraceptive agent, targets HSP90AB1 (HSP90BETA) and EEF1A1 (eEF1A), and stimulates Il1a transcription in rat sertoli cells. Biology of Reproduction. 2008;78(6):1139–1152. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.062679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rodriguez S, Jafer O, Goker H, Summersgill BM, Zafarana G, Gillis AJM, van Gurp RJHLM, Oosterhuis JW, Lu YJ, Huddart R, et al. Expression profile of genes from 12p in testicular germ cell tumors of adolescents and adults associated with i (12p) and amplification at 12p11. 2–p12. 1. Oncogene. 2003;22(12):1880–1891. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Juric Dejan, Sale Sanja, Hromas Robert A, Yu Ron, Wang Yan, Duran George E, Tibshirani Robert, Einhorn Lawrence H, Sikic Branimir I. Gene expression profiling differentiates germ cell tumors from other cancers and defines subtype-specific signatures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102(49):17763–17768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509082102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Guo J, Zhu P, Wu C, Yu L, Zhao S, Gu X. In silico analysis indicates a similar gene expression pattern between human brain and testis. Cytogenetic and Genome Research. 2003;103(1-2):58–62. doi: 10.1159/000076290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Neuvians Tanja Pascale, Gashaw Isabella, Sauer Christian Georg, von Ostau Christian, Kliesch Sabine, Bergmann Martin, Häcker Axel, Grobholz Rainer. Standardization strategy for quantitative PCR in human seminoma and normal testis. Journal of Biotechnology. 2005;117(2):163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Winge SB, Nielsen J, Jørgensen A, Owczarek S, Ewen KA, Nielsen JE, Juul A, Berezin V, Rajpert-De Meyts E. Biglycan is a novel binding partner of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3c (FGFR3c) in the human testis. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2015;399:235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2014.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Oji Yusuke, Tatsumi Naoya, Fukuda Mari, Nakatsuka Shin-Ichi, Aoyagi Sayaka, Hirata Erika, Nanchi Isamu, Fujiki Fumihiro, Nakajima Hiroko, Yamamoto Yumiko, et al. The translation elongation factor eEF2 is a novel tumor-associated antigen overexpressed in various types of cancers. International Journal of Oncology. 2014;44(5):1461–1469. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hovey Adriann M, Devor Eric J, Breheny Patrick J, Mott Sarah L, Dai Donghai, Thiel Kristina W, Leslie Kimberly K. miR-888: a novel cancer-testis antigen that targets the progesterone receptor in endometrial cancer. Translational oncology. 2015;8(2):85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hawkins Shannon M, Buchold Gregory M, Matzuk Martin M. Minireview: the roles of small rna pathways in reproductive medicine. Molecular Endocrinology. 2011;25(8):1257–1279. doi: 10.1210/me.2011-0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Belleannée Clémence, Calvo Ezéquiel, Thimon V´eronique, Cyr Daniel G, Légaré Christine, Garneau Louis, Sullivan Robert. Role of micrornas in controlling gene expression in different segments of the human epididymis. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e34996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang Jinsong, Liu Qiang, Zhang Wei, Li Jianyuan, Li Zheng, Tang Zhongyi, Li Yixue, Han Chunsheng, Hall Susan H, Zhang Yonglian. Comparative profiling of genes and miRNAs expressed in the newborn, young adult, and aged human epididymides. Acta biochimica et biophysica Sinica. 2010;42(2):145–153. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Goedeke Leigh, Vales-Lara Frances M, Fenstermaker Michael, Cirera-Salinas Daniel, Chamorro-Jorganes Aranzazu, Ramírez Cristina M, Mattison Julie A, de Cabo Rafael, Suárez Yajaira, Fernández-Hernando Carlos. A regulatory role for microRNA 33* in controlling lipid metabolism gene expression. Molecular and cellular biology. 2013;33(11):2339–2352. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01714-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen Zheng, Ye Jing, Ashraf Usama, Li Yunchuan, Wei Siqi, Wan Shengfeng, Zohaib Ali, Song Yunfeng, Chen Huanchun, Cao Shengbo. MicroRNA-33a-5p modulates Japanese encephalitis virus replication by targeting eukaryotic translation Elongation Factor 1A1. Journal of virology. 2016;90(7):3722–3734. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03242-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Xu Miaofei, Qin Yufeng, Qu Jianhua, Lu Chuncheng, Wang Ying, Wu Wei, Song Ling, Wang Shoulin, Chen Feng, Shen Hongbing, et al. Evaluation of five candidate genes from GWAS for association with oligozoospermia in a Han Chinese population. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e80374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Salas-Huetos Albert, Blanco Joan, Vidal Francesca, Godo Anna, Grossmann Mark, Pons Maria Carme, Silvia F, Garrido Nicolás, Anton Ester, et al. Spermatozoa from patients with seminal alterations exhibit a differential micro-ribonucleic acid profile. Fertility and sterility. 2015;104(3):591–601. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yan Naihong, Lu Yilu, Sun Huaqin, Tao Dachang, Zhang Sizhong, Liu Wenying, Ma Yongxin. A microarray for microRNA profiling in mouse testis tissues. Reproduction. 2007;134(1):73–79. doi: 10.1530/REP-07-0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tsatsanis Christos, Bobjer Johannes, Rastkhani Hamideh, Dermitzaki Erini, Katrinaki Marianna, Margioris Andrew N, Giwercman Yvonne Lundberg, Giwercman Aleksander. Serum miR-155 as a potential biomarker of male fertility. Human Reproduction. 2015;30(4):853–60. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Liu Te, Cheng Weiwei, Gao Yongtao, Wang Hui, Liu Zhixue. Microarray analysis of microRNA expression patterns in the semen of infertile men with semen abnormalities. Molecular medicine reports. 2012;6(3):535–542. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Si ML, Zhu S, Wu H, Lu Z, Wu F, Mo YY. miR-21-mediated tumor growth. Oncogene. 2007;26(19):2799–2803. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sicard Flavie, Gayral Marion, Lulka Hubert, Buscail Louis, Cordelier Pierre. Targeting miR-21 for the therapy of pancreatic cancer. Molecular Therapy. 2013;21(5):986–994. doi: 10.1038/mt.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Seni Giovanni, Elder John F. Ensemble methods in data mining: improving accuracy through combining predictions. Synthesis Lectures on Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery. 2010;2(1):1–126. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang Pengyi, Yang Yee Hwa, Zhou Bing B, Zomaya Albert Y. A review of ensemble methods in bioinformatics. Current Bioinformatics. 2010;5(4):296–308. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supp. 1: The list of top-ranked 500 interactions using TaLasso and GenMiR++ in TGCT.

Supp. 2: The list of common interactions among top-ranked 500 interactions between TaLasso and GenMiR++ in TGCT.

Supp. 3: The list of common interactions among top-ranked 500 interactions between TaLasso and GenMiR++ in prostate.

Supp. 4: List of pathways and involved genes.

Supp. 5: List of pathways and p-values.

Supp. 6: mRNA and miRNA data files as ‘*.RData’.

Supp. 7: A short note on the required preprocessing steps of level 3.0 TCGA data.

Code for reproducing results of experiments at GitHub repository, ‘FCS-miRNA-mRNA-Net’19.