Abstract

Purpose

ErbB2 signaling appears to be increased and may enhance AR activity in a subset of CRPC, but agents targeting ErbB2 have not been effective. This study was undertaken to assess ErbB2 activity in abiraterone-resistant prostate cancer (PCa), and determine whether it may contribute to androgen receptor (AR) signaling in these tumors.

Experimental Design

AR activity and ErbB2 signaling were examined in the radical prostatectomy specimens from a neoadjuvant clinical trial of leuprolide plus abiraterone, and in the specimens from abiraterone-resistant CRPC xenograft models. The effect of ErbB2 signaling on AR activity was determined in two CRPC cell lines. Moreover, the effect of combination treatment with abiraterone and an ErbB2 inhibitor was assessed in a CRPC xenograft model.

Results

We found that ErbB2 signaling was elevated in residual tumor following abiraterone treatment in a subset of patients, and was associated with higher nuclear AR expression. In xenograft models, we similarly demonstrated that ErbB2 signaling was increased and associated with AR reactivation in abiraterone-resistant tumors. Mechanistically, we show that ErbB2 signaling and subsequent activation of the PI3K/AKT signaling stabilizes AR protein. Furthermore, concomitantly treating CRPC cells with abiraterone and an ErbB2 inhibitor, lapatinib, blocked AR reactivation and suppressed tumor progression.

Conclusions

ErbB2 signaling is elevated in a subset of abiraterone-resistant prostate cancer patients and stabilizes AR protein. Combination therapy with abiraterone and ErbB2 antagonists may be effective for treating the subset of CRPC with elevated ErbB2 activity.

Keywords: prostate cancer, androgen receptor, castration-resistant, abiraterone, HER2, ERBB2, ERBB3, lapatinib

INTRODUCTION

Androgen receptor (AR) is critical for the development of prostate cancer (PCa) and most patients with metastatic PCa respond to androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), but they generally develop recurrent cancer within a few years despite castrate androgen levels (castration-resistant prostate cancer, CRPC). Androgen receptor activity in CRPC is partially restored through mechanisms that include increased intratumoral androgen synthesis (1–4), and many of these patients respond to agents that further suppress androgen synthesis (CYP17A1 inhibitor abiraterone) or to a more potent AR antagonist (enzalutamide). Unfortunately most of these patients relapse within a year and AR appears to again be reactivated in many of these relapsed tumors. This reactivation is likely through diverse mechanisms including further AR gene amplification, AR mutations, AR splice variants, and activation of kinase pathways that directly or indirectly enhance AR protein stability and sensitivity to low androgen levels (5–7).

Studies in cell line and xenograft models have indicated that increased ErbB2 signaling can contribute to the restoration of AR activity and tumor growth in CRPC (8–18). The physiological significance of ErbB2 in CRPC is supported by studies showing increased ErbB2 expression or activity in CRPC clinical samples (19–21), although this is not a consistent finding (22–24) and increased ErbB2 has also been associated with more aggressive primary untreated PCa (25). However, clinical trials of ErbB2 targeted therapies have not shown efficacy in PCa patients prior to androgen deprivation therapy or in CRPC (21, 26–31).

ErbB2 signals primarily through binding to and phosphorylation of ErbB3 at multiple sites, and ErbB3 expression may also be increased in CRPC and contribute to enhanced signaling through ErbB2 as well as EGFR (9, 32, 33). PI3K/AKT pathway activation is a major downstream consequence of ErbB3 phosphorylation and has been linked to AR function, but whether it positively or negatively regulates AR signaling remains controversial. Several studies in human PCa cells have found that AKT can phosphorylate AR at a site in its N-terminal domain (Ser213) and thereby decrease AR transcriptional activity or enhance its ubiquitylation and degradation by MDM2 (34–36), while other studies show that AKT mediated phosphorylation of AR can increase AR protein and activity (17, 37–39). Further studies indicate that PIM1, rather than AKT, is the major mediator of AR Ser213 phosphorylation (40, 41), and that PI3K may enhance AR stability and activity by AKT independent mechanisms (15). Finally, one study in genetically engineered mice with prostate specific PTEN loss indicates that PI3K pathway activation suppresses AR expression (42), while another study found that AR transcriptional activity, but not AR expression, was decreased (43).

Overall these studies indicate that ErbB2 may contribute to AR activity and tumor growth in at least a subset of patients with CRPC, and suggest that it may similarly or to a greater extent contribute to progression when androgen levels are further reduced with abiraterone. To test this hypothesis we examined ErbB2 activity in residual tumor in a recent clinical trial of neoadjuvant leuprolide plus abiraterone (44), and in two PCa xenograft models of abiraterone resistance. The results in both models and in the clinical samples show that abiraterone resistance is associated with increased ErbB2 activity. Moreover, we find that AKT activation downstream of ErbB2 stabilizes AR in these models. Finally, we show that addition of lapatinib (dual EGFR and ErbB2 inhibitor) markedly enhances responses to abiraterone in CRPC xenografts. These results indicate that screening for ErbB2 activity may identify a subset of men with CRPC who will respond to combination therapy of abiraterone plus lapatinib.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pathology

The presence and extent of residual tumor and cellularity were reviewed by a panel of pathologists (44). Due to the significant histologic changes in response to ADT, tumor volume is difficult to be characterized accurately and residual cancer burden (RCB) was examined by the tumor volume corrected by tumor cellularity (44). AR and phspho-ErbB3 immunohistochemistry staining was evaluated by pathologists. Total AR score is defined as nuclear intensity score (1=weak; 2=moderate; 3=strong) multiplied by nuclear percentage score (1=1–10%; 2=11–50%; 3=51–100%). Phospho-ErbB3 score is defined by intensity of the membrane staining (0=negative; 1=weak; 2=moderate; 3=strong).

Cell lines and cell culture

The LAPC4 and LNCaP-derived C4-2 cells were recently authenticated using short tandem repeat (STR) profiling by DDC Medical (Fairfield, OH). LAPC4-CS and –CR cells were derived from LAPC4 xenograft tumors. LAPC4-CR and C4-2 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 2% FBS and 8% CSS (charcoal-dextran stripped serum) (Hyclone) and LAPC4-CS cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS. For androgen stimulation assays, cells were grown to 50–60% confluence in medium containing 5% CSS for 3 days and then treated with DHT or inhibitors for 24 hour.

Xenograft study

LAPC4 xenografts were established in the flanks of male scid mice by injecting ~2 million cells in 50% Matrigel. When the tumors reached ~1 cm, tumor biopsies (for baseline gene expression) were obtained and then the mice were castrated. Additional biopsies were obtained 1 week after castration and at relapse (~3–4 weeks). Mice were then treated with abiraterone through daily ip injection (1–2mg/animal). The treatment is continued for ~5–6 weeks until the tumors grew beyond allowable sizes. For analysis of tumor samples, frozen sections were examined to confirm that the samples used for RNA and protein extraction contained predominantly non-necrotic tumor.

RT-PCR and immunoblotting

RNA was extracted from cultured cells and tumors using RNeasy Purification Kit (QIAGEN). Quantitative real-time RT-PCR amplification was with Taqman one-step RT-PCR reagents and results were normalized to co-amplified GAPDH. Primers and probes are listed as below: PSA: Forward, 5′-GATGAAACAGGCTGTGCCG-3′; Reverse, 5′-CCTCACAGCTACCCACTGCA-3′; Probe, 5′-FAM-CAGGAACA AAAGCGTGATCTTGCTGGG-3′. TMPRSS2: Forward, 5′-CCTGTGTGCCAAGACGACTG-3′; Reverse, 5′-TTATAGCCCATGTCCCTGCAG-3′; Probe, 5′-FAM-AACGAGAACTACGGGCGGGCG-3′. AR: Forward, 5′-GGAATTCCTGTGCATGAAA-3′; Reverse, 5′-CGAAGTTCATCAAAGAATT-3′; Probe, 5′-FAM-CTTCAGCATTATTCCAGTG-3′. FKBP5 primers were directly purchased from Thermal Fisher Scientific. Proteins were extracted by boiling for 15 min in 2% SDS and detected by blotting with anti-AR, anti-β-tubulin (Millipore), anti-PSA (BioDesign), anti-ErbB3(p-Tyr1289), anti-AKT(p-Ser473), anti-ErbB2, anti-ErbB3, anti-p110α, anti-p110β (Cell Signaling), or anti-β-actin (Abcam).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

C4-2 cell lines were treated with 10nM of DHT for 4 hours, followed by ChIP-Seq analyses as previously described (45). Briefly, chromatin immunoprecipitation was carried out using anti-AR antibody (Santa Cruz, Sc-816x), followed by qPCR analysis using the SYBR Green method on the QuantStudio 3 Real-time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The primers were listed below: PSA-Enhancer (ARE3): Forward, 5′-GCCTGGATCTGAGAGAGATATCATC-3′; Reverse, 5′-ACACCTTTTTTTTTCTGGATTGTTG-3′; TMPRSS2-Enhancer (−14kb): Forward, 5′-TGGTCCTGGATGATAAAAAAAGTTT-3′; Reverse, 5′-GACATACGCCCCACAACAGA-3′.

Phospho-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase array

Cells lysates were collected using lysis buffer and incubated with Phospho-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase array membranes (R&D Systems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues were cut into 4-μm-thick serial sections. Deparaffinization and epitope retrieval was performed by EnVision™ FLEX, pH 6.0 or 9.0 (Link-K8000, Dako). Immunostaining was performed using a Dako autostainer (Autostainer Link 48; Dako), and the reaction was visualized by DAB. The primary antibodies are anti-AR N-20 (Santa Cruz), anti-ErbB3(p-Tyr1289) (Cell Signaling), and anti-S6(p-Ser235/236) (Cell Signaling).

Statistical analyses

Data in bar graphs represent means±SD of at least 3 biological repeats. Statistical analyses were performed by Pearson’s Chi-square test (for Figure 1C), Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for Table 1), ANOVA test (for Figure 2A and 5A), and Student’s t-test (for Figure 3F, 4A, 4E, 4F, 4K, and 5C). p-Value<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant (indicated as *).

Figure 1. ErbB2 activity is increased in human PCa samples from an abiraterone plus leuprolide neoadjuvent trial.

A, Immunohistochemistry staining of phosphorylated ErbB3 (p-ErbB3) and AR of residual tumors in prostatectomy specimens from an abiraterone plus leuprolide neoadjuvant clinical trial. Membranous expression of p-ErbB3 was graded using intensity (0=negative, 1=weak, 2=modest, and 3=strong). 9 of 48 samples were positive for p-ErbB3. Three representative p-ErbB3 positive cases (score 2) were shown here. B, Immunohistochemistry staining of p-ErbB3 and AR of untreated (hormone-naïve) tumors in prostatectomy specimens. Only 2 out of 43 were positive for p-ErbB3. The three examples shown here were scored 0 (left panel), 1 (middle panel), and 2 (right panel). C, Statistical analysis of p-ErbB3 level in abiraterone plus leuprolide treated PCa samples versus untreated samples.

Table 1.

Nuclear AR expression was increased in the phospho-ErbB3 positive subset of abiraterone-resistant tumors.

| # of Cases | Median RCB | Median AR Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-ErbB3 (−) | 39 | 0.192 cm3 (IQR: 0.025 – 0.792) | 3 (IQR: 2 – 6) |

| p-ErbB3 (+) | 9 | 0.936 cm3 (IQR: 0.252 – 4.234) | 6 (IQR: 6 – 9) |

| Wilcoxon rank-sum Test: p = 0.05 | Wilcoxon rank-sum Test: p = 0.0003 | ||

Note: AR score: determined by nuclear intensity and nuclear percentage. RCB: Residual Cancer Burden. IQR: Interquartile Range.

Figure 2. AR is reactivated in abiraterone-resistant PCa xenografts.

A, LAPC4 cells were injected into the flanks of male SCID mice to develop androgen-dependent xenograft tumor (AD). Mice bearing established tumors were then castrated but tumors developed resistance within 3–4 weeks (CRPC). At this castration-resistant stage, mice were treated with abiraterone (1mg/day) through daily ip injection, and after one week the treatment was increased dose to 2mg/day. Tumor growth was initially decreased but resumed after 3 weeks (Abi-resistant). Multiple time points during the treatment and tumor progression were selected for tumor biopsies as indicated. Androgen regulated PSA and TMPRSS2 expression was examined by qRT-PCR. B, AR expression was examined using immunohistochemistry staining. C, The expressions of 6 androgen synthetic genes (AKR1C3 is undetected) was examined by qRT-PCR. D, Testosterone, DHT, and androstenedione levels in abiraterone-treated LAPC4 xenograft tumor biopsies were measured using mass spectrometry.

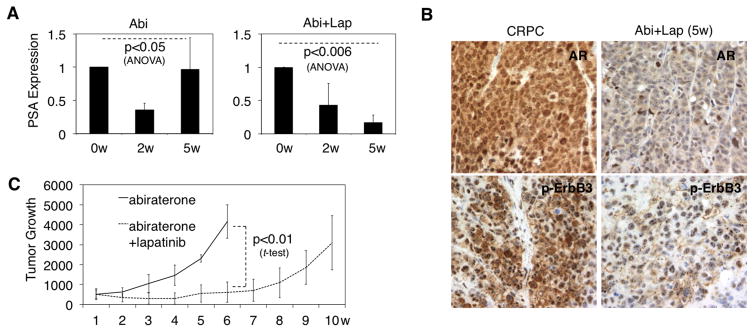

Figure 5. Combined treatment with abiraterone and lapatinib delays relapse of LAPC4 xenograft tumor.

A, Mice bearing castration-resistant LAPC4 xenograft were treated with abiraterone alone or abiraterone plus lapatinib. PSA mRNA expression was determined by qRT-PCR in the tumor biopsies at 0, 2, and 5 weeks after treatment. B, AR and p-ErbB3 protein expression was examined using immunohistochemistry staining. C, Tumor volume was measured at 1–10 weeks after treatment. Note: the tumor treated with abiraterone alone reached the maximal allowed size at ~6w and the mice were hence sacrificed.

Figure 3. ErbB2 activity is increased in abiraterone-resistant xenografts.

A, Immunohistochemistry staining of p-ErbB3 and p-S6 in three stages of LAPC4 xenograft biopsies as indicated. B, Immunohistochemistry staining of p-ErbB3 in previously established abiraterone-resistant VCaP xenograft biopsies. C, Cells from the LAPC4 xenograft prior to castration (LAPC4-CS) and from the castration-resistant stage (LAPC4-CR) were extracted and grown in tissue culture. ErbB2 signaling was examined by immunoblotting in LAPC4-CS versus -CR cells treated with 10μM lapatinib (dual EGFR/ErbB2 inhibitor). D, Cell lysate from LAPC4-CS and CR cells were subject to Phospho-RTK Array membranes (R&D SYSTEMS) to immunoblot a group of phosphorylated-receptor tyrosine kinases, phosphorylated-tyrosine, and IgG controls (duplicates). E and F, AR protein and mRNA expression in LAPC4-CS versus -CR cells was examined by immunoblotting (D) and qRT-PCR (E).

Figure 4. ErbB2 and downstream PI3K/AKT pathway activation stabilizes AR protein and increases its activity in CRPC cells.

A, mRNA expressions of PSA and FKBP5 in LAPC4-CR cells treated with 10μM lapatinib, BKM120 (PI3K inhibitor), AKT-viii (AKT inhibitor), or TAK165 (ErbB2 inhibitor) for 24h were examined by qRT-PCR. B, Protein expressions of AR and p-AKT were examined by immunoblotting. C, LAPC4-CR cells were pretreated with DMSO or 10μM lapatinib for 4h and then treated with cycloheximide (CHX, 10μg/ml) for 0–4 h. AR protein half-life was examined by immunoblotting. D, Protein expressions of AR, PSA, and p-AKT in C4-2 cells treated with DHT alone (10nM) or DHT plus 10μM lapatinib (24h) were immunoblotted. E, AR binding intensity at androgen-responsive enhancers of PSA and TMPRSS2 genes in C4-2 cells (DHT 4h) was examined by ChIP-qPCR. F, mRNA expressions of PSA and TMPRSS2 were examined by qRT-PCR. G, AR protein half-life (CHX for 0-2.5h) in C4-2 cells treated with DMSO or 10μM lapatinib was measured by immunoblotting. H, C4-2 cells were pretreated with DMSO or 10μM lapatinib for 4h and then treated with combination of MG115/MG132 for 4h. AR protein was then immunoblotted. I, The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of AR protein expression in C4-2 cells treated with DHT or DHT plus 10μM lapatinib (24h) were examined using cell fractionation assay (Subcellular Protein Fractionation Kit provided by Thermo Scientific) followed by immunoblotting. J, Protein expressions of AR, AKT, and p-AKT in C4-2 cells treated with DHT or DHT plus 10μM AKT-x for 24h were measured by immunoblotting. K, mRNA expressions of PSA and FKBP5 were examined by qRT-PCR. L, The nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of AR protein expression in C4-2 cells treated with 10μM lapatinib, AKT-viii, or AKT-x for 24h were examined using cell fractionation assay followed by immunoblotting. M, Protein expressions of AR and p-AKT in C4-2 cells treated with DHT (0–10nM) plus A66 (25μM) or TGX221 (25μM) for 24h were immunoblotted.

RESULTS

ErbB2 activity is increased and associated with nuclear AR expression in PCa samples from an abiraterone plus leuprolide neoadjuvant trial

To study the possible role of ErbB2 in abiraterone resistance, we examined radical prostatectomy specimens from patients enrolled in a phase II neoadjuvant trial of leuprolide for 24 weeks in combination with abiraterone for 12 or 24 weeks (44). Using an antibody specific for an ErbB2 target site on ErbB3 (Tyr1289) that mediates PI3K activation, we found membrane staining in residual tumors in 9 of the 48 cases examined (Fig. 1A). In contrast, in a series of untreated PCa samples matched for initial Gleason scores, we found weak to moderate phospho-ErbB3 staining in only 2 of 43 cases (Fig. 1B), a difference that was statistically significant (Fig. 1C). These 9 phospho-ErbB3 positive cases in the neoadjuvant trial also had greater residual cancer burden (RCB) in the radical prostatectomy specimens compared to the 39 phospho-ErbB3 negative cases (Table 1). Finally, levels of nuclear AR (as assessed by AR score) were also increased in the phospho-ErbB3 positive cases (Table 1). Together these results support the hypothesis that increased ErbB2 activity contributes to abiraterone resistance.

AR is reactivated in abiraterone-resistant PCa xenografts

ErbB2 activity in the LAPC4 PCa cell line and its derived CRPC model has been shown to enhance AR expression and activity in previous studies (10, 15). Therefore, we developed a xenograft model from LAPC4 cells to mimic tumor progression to abiraterone resistance. Androgen-dependent LAPC4 cells were injected into the flanks of male SCID mice and xenograft tumors were developed within ~8 weeks. Mice bearing established xenograft tumors were then castrated, which initially blunted growth, but within 3–4 weeks tumors resumed growing. At this castration-resistant stage we started treatment with abiraterone (1mg/day) through daily intraperitoneal injection, and after one week the treatment was increased to 2mg/day. Tumor growth was initially decreased by abiraterone, but tumors progressed after ~3 weeks.

Multiple time points during the treatment and tumor progression were selected for tumor biopsies as indicated in Fig. 2A. Androgen regulated PSA and TMPRSS2 expression was initially blocked by castration, but was restored in ~3 weeks (Fig. 2A). The subsequent abiraterone treatment rapidly decreased PSA and TMPRSS2 expression in the CRPC stage, but expression was once again fully restored by ~5–6 weeks despite the continuous treatment with abiraterone (Fig. 2A). Consistent with the restoration of transcriptional activity, AR also regained nuclear staining in the CRPC and abiraterone-resistant stages (Fig. 2B). As increased expression of CYP17A1 has been reported in abiraterone-resistant tumor cells (45, 46), we next assessed the expression of a panel of androgen synthetic enzymes including CYP17A1 in abiraterone-resistant tumors versus tumors prior to the treatment. However, we were unable to detect any consistent increased expression of androgen synthetic genes, and AKR1C3 was undetectable (Fig. 2C). We also directly measured intratumoral androgen levels (testosterone, DHT, and androstenedione) by mass spectrometry. Interestingly, unlike VCaP CRPC xenograft tumors producing high DHT (45, 46), testosterone (T) appeared to be the major type of androgen in these tumor cells and its level was rapidly decreased by abiraterone treatment (Fig. 2D). Significantly, androgen levels remained low if not lower in abiraterone-resistant versus -responsive tumors (Fig. 2D), suggesting that increased intratumoral androgen synthesis was unlikely to be the basis for AR reactivation. As selection for progesterone-responsive AR mutants was recently reported as a mechanism of abiraterone resistance (5, 45), we next sequenced AR in all the xenografts tumor samples. However, we did not detect any AR mutations, and similarly did not detect increased expression of the AR-V7 or AR567es splice variants in the abiraterone-resistant tumors (not shown).

Abiraterone-resistant xenografts have increased ErbB2 activity

We next examined ErbB2 activity in the LAPC4 xenografts and found that Tyr1289-phosphorylated ErbB3 was strongly increased in the CRPC xenografts versus prior to castration, and was further elevated in the abiraterone-resistant tumors (Fig. 3A, upper panel). As activation of ErbB2 leads to the subsequent activation of PI3K and AKT, we then examined the AKT activity in those xenograft tumors. Consistent with increased ErbB2 activity, Ser235/236 phosphorylated S6 (p-S6) staining (downstream of AKT/mTOR) was also elevated in CRPC and further increased in the abiraterone-resistant tumors (Fig. 3A, lower panel). Examination of p-ErbB3 in a previously established abiraterone-resistant VCaP xenograft model (45) similarly indicated an increase of ErbB2 activity (Fig. 3B).

We then extracted cells from the LAPC4 xenograft prior to castration (castration-sensitive, LAPC4-CS) and from the castration-resistant stage (LAPC4-CR) to grow in tissue culture (we were unable to establish cell lines from the abiraterone-resistant stage). Consistent with the xenograft results, p-ErbB3 was increased in the LAPC4-CR cells, and could be ablated in both cell lines by treatment with lapatinib (dual EGFR/ErbB2 inhibitor), which also markedly reduced Ser473 phosphorylated AKT (p-AKT) (Fig. 3C). Significantly, ErbB2 and ErbB3 protein levels were not increased in the LAPC4-CR cells (Fig. 3C), and examination of mRNA in the xenografts similarly indicated that ERBB2 and ERBB3 expression were not increased with progression to CRPC and abiraterone resistance (Fig. S1A). Based on this observation, we examined ERBB2 and ERBB3 mRNA levels in our previously reported set of primary PCa and metastatic CRPC clinical samples and found no significant increases in ERBB2 or ERBB3 expression in the CRPC samples (Fig. S1B) (2). These observations suggest that increased ligand, decreased phosphatase activity, or other mechanisms distinct from increased ERBB2 or ERBB3 expression may be contributing to increased ErbB3 phosphorylation in vivo.

Furthermore, we carried out a phospho-receptor tyrosine kinase array assay (Phospho-RTK Array, including 42 RTKs) to identify additional receptor tyrosine kinases that may be more activated in CRPC. As seen in Fig. 3D, we have detected a substantial increase of phosphorylation on all ErbB family members (EGFR, ErbB2, ErbB3, and ErbB4) in LAPC4-CR cells versus CS cells, and ErbB2 phosphorylation appeared to be the strongest amongst the group. In addition to ErbB family, we only detected weak FGFR3 phosphorylation in LAPC4-CR cells that is not present in CS cells. The total phospho-tyrosine signal was not increased in LAPC4-CR cells. Collectively, the results from this unbiased approach further confirmed our observation that ErbB2 signaling was significantly induced in castration-resistant PCa models.

Finally, also consistent with the xenograft data, AR protein expression was increased in the LAPC4-CR cells versus LAPC4-CS cells (Fig. 3E). However, AR message was not increased (Fig. 3F), suggesting the increased protein may be due to decreased degradation.

ErbB2 and downstream PI3K/AKT pathway activation stabilizes AR protein and increases its activity in CRPC cells

We next examined the effect of ErbB2 on AR expression and activity in the LAPC4-CR cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, treating with lapatinib markedly suppressed the androgen-induced expression of the PSA and FKBP5 genes. Blocking ErbB2 downstream signaling through PI3K by BKM120 (PI3K inhibitor) or through AKT with AKT-viii (AKT inhibitor) similarly impaired AR transcriptional activity (Fig. 4A). Since lapatinib may also block EGFR activity, we used another inhibitor (TAK165) to specifically block ErbB2 and found that AR activity was similarly suppressed. It should be noted that EGFR downstream ERK activation is not readily detectable in these cells (not shown).

We then examined effects of ErbB2 on AR protein expression. Inhibition of ErbB2 by lapatinib or TAK165 markedly decreased AR protein in the absence or presence of androgens, and also decreased AKT activity (Fig. 4B). PI3K and AKT inhibitors similarly markedly decreased AR protein, indicating that the effects of ErbB2 inhibition were substantially or fully mediated through PI3 kinase (Fig. 4B). As ErbB2 inhibition did not significantly alter AR mRNA expression (Fig. S2), we next assessed effects on AR protein degradation. Using cycloheximide to block new protein synthesis, we found that lapatinib treatment substantially decreased the half-life of AR protein, indicating that ErbB2 signaling can decrease AR protein degradation (Fig. 4C).

We next examined another CRPC line (C4-2) that has high basal AR activity in steroid-depleted medium and is abiraterone-resistant (45). Treatment with heregulin, which stimulates ErbB2/ErbB3 heterodimerization, confirmed that ErbB2 signaling in C4-2 cells was intact and could be suppressed by lapatinib (Fig. S3). C4-2 cells also are PTEN deficient and thus have high basal PI3K/AKT pathway activity. Significantly, treatment of androgen-starved C4-2 cells with lapatinib decreased AKT activity and both AR and PSA protein (Fig. 4D). The suppression effect on AR protein occurred rapidly at 8-hour treatment (Fig. S4). Lapatinib treatment also decreased AR recruitment at androgen-responsive enhancers (Fig. 4E) and the expression of androgen-regulated genes (Fig. 4F). Consistent with the findings in LAPC4 cells, lapatinib did not decrease AR mRNA levels (Fig. S5A), but instead decreased AR protein half-life (Fig. 4G) and increased its proteasome-dependent degradation (Fig. 4H).

To further examine if lapatinib treatment could affect AR nuclear localization, we carried out cell fractionation assays and measured AR cytoplasmic and nuclear protein expression. As seen in Fig. 4I, while lapatinib treatment decreased cytoplasmic expression of AR, it more markedly diminished androgen-induced AR nuclear expression, suggesting that ErbB2 inhibition has more significant impact on nuclear AR protein expression. To exclude the possibility that the decrease of AR protein by inhibitor treatments is due to blocking other kinase activity, we used RNAi to silence ErbB2. As shown in Fig. S6, total AR protein expression was modestly reduced by siRNA against ERBB2 gene and nuclear AR expression was more substantially reduced. This supports the results with the small molecule inhibitors, which may be more effective due to their more acute and complete suppression of ErbB2 activity.

Finally, similarly to lapatinib, treatment with an AKT inhibitor (AKT-x) markedly decreased basal AR protein and its transcriptional activity in androgen-starved C4-2 cells (Fig. 4J and K) without significantly affecting AR mRNA expression (Fig. S5B). Identical results were obtained with another AKT inhibitor (AKT-viii) (Fig. S7A–C). Similar to lapatinib treatment, both AKT inhibitor treatments diminished AR nuclear localization (Fig. 4L). AKT pathway is directly activated by upstream PI3K kinase, which consists p85 and p110 subunits. Two p110 isoforms (p110α and p110β) are commonly expressed in prostate cancer cells, but p110β appears to have a more profound impact on prostate cancer development (47–49). Therefore, we next used isoform specific inhibitors to determine whether p110α or p110β is responsible for stabilizing AR protein. As seen in Fig. 4M, the p110β-specific inhibitor (TGX221) blocked AKT activation and thereby significantly decreased AR protein expression while the p110α-specific inhibitor (A66) only modestly decreased AKT phosphorylation and this resulted in very weak effect on AR protein. Similar results were also obtained using RNAi approach (Fig. S8A and B). Knocking down both isoforms resulted in decrease of AKT activation, but the effect of silencing p110β on p-AKT is more significant. Consistent with these results, diminishing p110β but not p110α expression led to dramatic AR protein degradation. These results supported a critical role of p110β in mediating downstream AKT pathway and subsequent AR degradation in prostate cancer cells. Collectively, these results indicate that ErbB2 activation decreases AR protein degradation through downstream activation of AKT, and that this contributes to AR activity in castration-resistant and abiraterone-resistant PCa.

Combined treatment with abiraterone and lapatinib delays relapse

We next determined if treating CRPC xenografts with abiraterone in combination with lapatinib could delay or prevent the emergence of resistance. Castration-resistant LAPC4 xenografts in castrated mice were examined for AR expression and activity (based on PSA expression) after 2 or 5 weeks of treatment with abiraterone or abiraterone in combination with lapatinib. As shown in Fig. 5A and B, the combined treatment prevented the restoration of nuclear AR expression and AR activity after 5 weeks. Moreover, the combination therapy more effectively suppressed tumor growth and delayed tumor progression (Fig. 5C).

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have indicated that increased ErbB2 activity may contribute to more aggressive primary PCa or to the emergence of CRPC, and may function at least in part by enhancing AR activity through unclear mechanisms. However, clinical trials of ErbB2 inhibitors have not shown clear evidence of efficacy, and the role of ErbB2 in PCa remains to be established. We hypothesized that if increased ErbB2 activity was contributing to CRPC, then it may similarly or to a greater extent be a driver of resistance to agents such as abiraterone that further reduce androgen levels. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found evidence of increased ErbB2 activity, based on immunostaining for phospho-ErbB3, in a subset of residual tumors in radical prostatectomy specimens from men treated with neoadjuvant leuprolide plus abiraterone. Moreover, in two PCa xenograft models, LAPC4 and VCaP, we found that ErbB2 activity was increased with progression to CRPC and to abiraterone resistance. Finally, we found that treatment of castration-resistant LAPC4 xenografts with abiraterone plus lapatinib increased the time to progression versus single agent abiraterone. This latter result is consistent with recent studies indicating that EGFR/ErbB2 inhibition can sensitize PCa cells to androgen deprivation or enzalutamide (9, 16).

Significantly, both the residual cancer burden and AR expression score were higher in the phospho-ErbB3 positive versus negative neoadjuvant radical prostatectomies, consistent with AR being one target of increased ErbB2 activity. Similarly to the clinical samples, increased phospho-ErbB3 correlated with restoration of AR expression and activity in the castration-resistant and abiraterone-resistant LAPC4 and VCaP xenografts. The increased ErbB2 activity and AR expression were also observed in cell lines derived from castration-resistant versus castration-sensitive LAPC4 xenografts. Using the castration-resistant LAPC4 cell line we confirmed that ErbB2 inhibition markedly decreased AR transcriptional activity, and that this was associated with increased AR degradation. ErbB2 inhibition with lapatinib also suppressed PI3K/AKT activation, and treatment with a PI3K or AKT inhibitor (BKM120 and AKT-viii, respectively) mirrored the effects of lapatinib on increasing AR degradation. Finally, we found that lapatinib and AKT-x similarly increased the degradation of AR in another CRPC cell line, C4-2. Based on these results, we conclude that a major mechanism of action for ErbB2 signaling is to stabilize AR through activation of AKT.

Previous studies examining the effects of PI3K/AKT signaling on AR have yielded conflicting results. AKT has been reported to phosphorylate Ser213 in the AR N-terminus and thereby enhance its ubiquitylation and degradation in human PCa cells (34–36), but this effect may be cell line and passage number dependent (17, 37–39). Moreover, further studies indicate that PIM1 is the major mediator of AR Ser213 phosphorylation (40, 41), while another study found that PI3K enhanced AR stability and activity by AKT independent mechanisms (15). Studies in mice with prostate specific PTEN loss are also somewhat conflicting as one study found that PI3K pathway activation suppressed AR expression (42) while a second study found decreased AR transcriptional activity but not decreased AR expression (43). Overall these findings indicate that effects of the PI3K/AKT pathway on AR expression and activity may be modulated by multiple factors, including those mediating pathway activation (such as receptor tyrosine kinase activation versus PTEN loss), and possibly including species-specific differences in AKT signaling (50). Significantly, and consistent with a recent report (16), the increased AR expression we observed in phospho-ErbB3 positive clinical samples indicates that PI3K/AKT pathway activation mediated by ErbB2 does not decrease AR expression, and appears to instead increase its stability.

Mechanisms driving an increase in ErbB2 activity after androgen deprivation therapies also appear to be diverse. Androgen deprivation can activate AKT by decreasing expression of the FKBP5 gene, which is a chaperone for the AKT phosphatase PHLPP1 (51), and a recent study found that AKT could stimulate the YB1 transcription factor and thereby enhance ERBB2 gene transcription (16). Androgen deprivation may also increase ErbB3 expression and activity (9). Significantly, the increased ErbB2 activity in our models was not associated with increased ErbB2 or ErbB3 mRNA or protein, suggesting additional mechanisms that may include increased ligand production or decreases in a phosphatase. Therefore, due to these diverse mechanisms, it will be important to assess ErbB2 activity in clinical samples based on ErbB3 phosphorylation or other downstream effects, rather than on ErbB2 or ErbB3 mRNA or protein levels. Based on our results, we hypothesize that while lapatinib may have limited efficacy in unselected CRPC patients, it may be effective in the subset of patients with ErbB2 pathway activation, particularly if used in combination with abiraterone or enzalutamide.

Supplementary Material

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

The CYP17A1 inhibitor abiraterone is now a standard treatment for castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) and acts through further blocking androgen synthesis, but patients generally relapse within a year. Androgen receptor (AR) signaling appears to be reactivated in the majority of these abiraterone-resistant tumors, but the mechanisms remain to be established. In this study we have demonstrated that ErbB2 signaling is increased in a subset of abiraterone-resistant tumors and reactivates AR through stabilizing AR protein expression. Concomitantly treating CRPC cells with abiraterone and an EGFR/ErbB2 inhibitor, lapatinib, blocked AR reactivation and suppressed tumor progression. Based on these results, we suggest that while ErbB2 inhibition may have limited efficacy in unselected CRPC patients, it may be effective in the subset of patients with ErbB2 pathway activation, particularly if used in combination with abiraterone or enzalutamide.

Acknowledgments

Funding support: This work is supported by grants from NIH (R00CA166507 to C.C., P01CA163227 to S.P.B, P.S.N, E.A.M., and SPORE in Prostate Cancer P50CA090381-13 to C.C., S.P.B. and P50CA097186 to P.S.N., E.A.M), and DOD (W81XWH-11-1-0295 and W81XWH-13-1-0266 to S.P.B.), a DF/HCC Mazzone Impact Award, and by Awards from the Prostate Cancer Foundation.

We thank Drs. Brett Marck and Alvin Matsumoto (University of Washington, Seattle, WA) for mass spectrometry assays, and Janssen Global Services for the support of this research.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: P.S. Nelson and M.-E. Taplin are consultant/advisory board members for Janssen. M.-E. Taplin reports receiving a commercial research grant from Janssen. No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed by the other authors.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: S. Gao, H. Ye, H. Wang, A. Sharma, S.P. Balk, C. Cai

Development of methodology: S. Gao, H. Ye, S. Gerrin, H. Wang, A. Sharma, A. Patnaik, E.A. Mostaghel, S.P. Balk, C. Cai

Acquisition of data: S. Gao, H. Ye, O. Voznesensky, H. Wang, A. Sharma, S. Chen, W. Han, M.-E. Taplin, S.P. Balk, Cai

Analysis and interpretation of data: S. Gao, H. Ye, S. Gerrin, H. Wang, A. Sharma, S. Chen, A.G. Sowalsky, Z. Yu, E.A. Mostaghel, S.P. Balk, C. Cai

Writing, review, and/or revision of the manuscript: S. Gao, H. Ye, A.G. Sowalsky P.S. Nelson, M.-E. Taplin, S.P. Balk, C. Cai,

Administrative, technical, or material support: H. Ye, O. Voznesensky, P.S. Nelson, M.-E. Taplin, S.P. Balk, C. Cai

Study supervision: H. Ye, S.P. Balk, C. Cai

References

- 1.Titus MA, Schell MJ, Lih FB, Tomer KB, Mohler JL. Testosterone and dihydrotestosterone tissue levels in recurrent prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:4653–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stanbrough M, Bubley GJ, Ross K, Golub TR, Rubin MA, Penning TM, et al. Increased expression of genes converting adrenal androgens to testosterone in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2006;66:2815–25. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Montgomery RB, Mostaghel EA, Vessella R, Hess DL, Kalhorn TF, Higano CS, et al. Maintenance of intratumoral androgens in metastatic prostate cancer: a mechanism for castration-resistant tumor growth. Cancer research. 2008;68:4447–54. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Locke JA, Guns ES, Lubik AA, Adomat HH, Hendy SC, Wood CA, et al. Androgen levels increase by intratumoral de novo steroidogenesis during progression of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer research. 2008;68:6407–15. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen EJ, Sowalsky AG, Gao S, Cai C, Voznesensky O, Schaefer R, et al. Abiraterone treatment in castration-resistant prostate cancer selects for progesterone responsive mutant androgen receptors. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2015;21:1273–80. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ware KE, Garcia-Blanco MA, Armstrong AJ, Dehm SM. Biologic and clinical significance of androgen receptor variants in castration resistant prostate cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2014;21:T87–T103. doi: 10.1530/ERC-13-0470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan X, Cai C, Chen S, Chen S, Yu Z, Balk SP. Androgen receptor functions in castration-resistant prostate cancer and mechanisms of resistance to new agents targeting the androgen axis. Oncogene. 2014;33:2815–25. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger R, Lin DI, Nieto M, Sicinska E, Garraway LA, Adams H, et al. Androgen-dependent regulation of Her-2/neu in prostate cancer cells. Cancer research. 2006;66:5723–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Mooso BA, Jathal MK, Madhav A, Johnson SD, van Spyk E, et al. Dual EGFR/HER2 inhibition sensitizes prostate cancer cells to androgen withdrawal by suppressing ErbB3. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:6218–28. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Craft N, Shostak Y, Carey M, Sawyers CL. A mechanism for hormone-independent prostate cancer through modulation of androgen receptor signaling by the HER-2/neu tyrosine kinase. Nature medicine. 1999;5:280–5. doi: 10.1038/6495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregory CW, Whang YE, McCall W, Fei X, Liu Y, Ponguta LA, et al. Heregulin-induced activation of HER2 and HER3 increases androgen receptor transactivation and CWR-R1 human recurrent prostate cancer cell growth. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2005;11:1704–12. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyader C, Ceraline J, Gravier E, Morin A, Michel S, Erdmann E, et al. Risk of hormone escape in a human prostate cancer model depends on therapy modalities and can be reduced by tyrosine kinase inhibitors. PloS one. 2012;7:e42252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Majumder S, McCall W, Sartor CI, Mohler JL, Gregory CW, et al. Inhibition of HER-2/neu kinase impairs androgen receptor recruitment to the androgen responsive enhancer. Cancer research. 2005;65:3404–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mellinghoff IK, Tran C, Sawyers CL. Growth inhibitory effects of the dual ErbB1/ErbB2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor PKI-166 on human prostate cancer xenografts. Cancer research. 2002;62:5254–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mellinghoff IK, Vivanco I, Kwon A, Tran C, Wongvipat J, Sawyers CL. HER2/neu kinase-dependent modulation of androgen receptor function through effects on DNA binding and stability. Cancer cell. 2004;6:517–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shiota M, Bishop JL, Takeuchi A, Nip KM, Cordonnier T, Beraldi E, et al. Inhibition of the HER2-YB1-AR axis with Lapatinib synergistically enhances Enzalutamide anti-tumor efficacy in castration resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9086–98. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen Y, Hu MC, Makino K, Spohn B, Bartholomeusz G, Yan DH, et al. HER-2/neu promotes androgen-independent survival and growth of prostate cancer cells through the Akt pathway. Cancer research. 2000;60:6841–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yeh S, Lin HK, Kang HY, Thin TH, Lin MF, Chang C. From HER2/Neu signal cascade to androgen receptor and its coactivators: a novel pathway by induction of androgen target genes through MAP kinase in prostate cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:5458–63. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.10.5458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Y, Brands FH, Chatterjee S, Feng AC, Groshen S, Schewe J, et al. Her-2/neu expression in prostate cancer: high level of expression associated with exposure to hormone therapy and androgen independent disease. The Journal of urology. 2001;166:1514–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)65822-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Signoretti S, Montironi R, Manola J, Altimari A, Tam C, Bubley G, et al. Her-2-neu expression and progression toward androgen independence in human prostate cancer. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92:1918–25. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.23.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris MJ, Reuter VE, Kelly WK, Slovin SF, Kenneson K, Verbel D, et al. HER-2 profiling and targeting in prostate carcinoma. Cancer. 2002;94:980–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Calvo BF, Levine AM, Marcos M, Collins QF, Iacocca MV, Caskey LS, et al. Human epidermal receptor-2 expression in prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2003;9:1087–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Savinainen KJ, Saramaki OR, Linja MJ, Bratt O, Tammela TL, Isola JJ, et al. Expression and gene copy number analysis of ERBB2 oncogene in prostate cancer. The American journal of pathology. 2002;160:339–45. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64377-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lara PN, Jr, Meyers FJ, Gray CR, Edwards RG, Gumerlock PH, Kauderer C, et al. HER-2/neu is overexpressed infrequently in patients with prostate carcinoma. Results from the California Cancer Consortium Screening Trial. Cancer. 2002;94:2584–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neto AS, Tobias-Machado M, Wroclawski ML, Fonseca FL, Teixeira GK, Amarante RD, et al. Her-2/neu expression in prostate adenocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of urology. 2010;184:842–50. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whang YE, Armstrong AJ, Rathmell WK, Godley PA, Kim WY, Pruthi RS, et al. A phase II study of lapatinib, a dual EGFR and HER-2 tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:82–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de Bono JS, Bellmunt J, Attard G, Droz JP, Miller K, Flechon A, et al. Open-label phase II study evaluating the efficacy and safety of two doses of pertuzumab in castrate chemotherapy-naive patients with hormone-refractory prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:257–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sridhar SS, Hotte SJ, Chin JL, Hudes GR, Gregg R, Trachtenberg J, et al. A multicenter phase II clinical trial of lapatinib (GW572016) in hormonally untreated advanced prostate cancer. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33:609–13. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e3181beac33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ziada A, Barqawi A, Glode LM, Varella-Garcia M, Crighton F, Majeski S, et al. The use of trastuzumab in the treatment of hormone refractory prostate cancer; phase II trial. Prostate. 2004;60:332–7. doi: 10.1002/pros.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lara PN, Jr, Chee KG, Longmate J, Ruel C, Meyers FJ, Gray CR, et al. Trastuzumab plus docetaxel in HER-2/neu-positive prostate carcinoma: final results from the California Cancer Consortium Screening and Phase II Trial. Cancer. 2004;100:2125–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agus DB, Sweeney CJ, Morris MJ, Mendelson DS, McNeel DG, Ahmann FR, et al. Efficacy and safety of single-agent pertuzumab (rhuMAb 2C4), a human epidermal growth factor receptor dimerization inhibitor, in castration-resistant prostate cancer after progression from taxane-based therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:675–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koumakpayi IH, Diallo JS, Le Page C, Lessard L, Gleave M, Begin LR, et al. Expression and nuclear localization of ErbB3 in prostate cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2006;12:2730–7. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen L, Siddiqui S, Bose S, Mooso B, Asuncion A, Bedolla RG, et al. Nrdp1-mediated regulation of ErbB3 expression by the androgen receptor in androgen-dependent but not castrate-resistant prostate cancer cells. Cancer research. 2010;70:5994–6003. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin HK, Yeh S, Kang HY, Chang C. Akt suppresses androgen-induced apoptosis by phosphorylating and inhibiting androgen receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7200–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121173298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaughan L, Logan IR, Neal DE, Robson CN. Regulation of androgen receptor and histone deacetylase 1 by Mdm2-mediated ubiquitylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:13–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taneja SS, Ha S, Swenson NK, Huang HY, Lee P, Melamed J, et al. Cell-specific regulation of androgen receptor phosphorylation in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40916–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ha S, Ruoff R, Kahoud N, Logan SK, Franke TF. Androgen receptor levels are upregulated by Akt in prostate cancer. Endocrine-related cancer. 2011 doi: 10.1530/ERC-10-0204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lin HK, Hu YC, Lee DK, Chang C. Regulation of androgen receptor signaling by PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog deleted on chromosome 10) tumor suppressor through distinct mechanisms in prostate cancer cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:2409–23. doi: 10.1210/me.2004-0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin HK, Hu YC, Yang L, Altuwaijri S, Chen YT, Kang HY, et al. Suppression versus induction of androgen receptor functions by the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in prostate cancer LNCaP cells with different passage numbers. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:50902–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300676200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ha S, Iqbal NJ, Mita P, Ruoff R, Gerald WL, Lepor H, et al. Phosphorylation of the androgen receptor by PIM1 in hormone refractory prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2012 doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linn DE, Yang X, Xie Y, Alfano A, Deshmukh D, Wang X, et al. Differential regulation of androgen receptor by PIM-1 kinases via phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of distinct ubiquitin E3 ligases. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22959–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.338350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Chen Y, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer cell. 2011;19:575–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mulholland DJ, Tran LM, Li Y, Cai H, Morim A, Wang S, et al. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer cell. 2011;19:792–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taplin ME, Montgomery B, Logothetis CJ, Bubley GJ, Richie JP, Dalkin BL, et al. Intense androgen-deprivation therapy with abiraterone acetate plus leuprolide acetate in patients with localized high-risk prostate cancer: results of a randomized phase II neoadjuvant study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3705–15. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.4578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai C, Chen S, Ng P, Bubley GJ, Nelson PS, Mostaghel EA, et al. Intratumoral de novo steroid synthesis activates androgen receptor in castration-resistant prostate cancer and is upregulated by treatment with CYP17A1 inhibitors. Cancer research. 2011;71:6503–13. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mostaghel EA, Marck BT, Plymate SR, Vessella RL, Balk S, Matsumoto AM, et al. Resistance to CYP17A1 inhibition with abiraterone in castration-resistant prostate cancer: induction of steroidogenesis and androgen receptor splice variants. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2011;17:5913–25. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jiang X, Chen S, Asara JM, Balk SP. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway activation in phosphate and tensin homolog (PTEN)-deficient prostate cancer cells is independent of receptor tyrosine kinases and mediated by the p110beta and p110delta catalytic subunits. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14980–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.085696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee SH, Poulogiannis G, Pyne S, Jia S, Zou L, Signoretti S, et al. A constitutively activated form of the p110beta isoform of PI3-kinase induces prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:11002–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005642107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li B, Sun A, Jiang W, Thrasher JB, Terranova P. PI-3 kinase p110beta: a therapeutic target in advanced prostate cancers. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2014;2:188–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang H, Xu Y, Fang Z, Chen S, Balk SP, Yuan X. Doxycycline regulated induction of AKT in murine prostate drives proliferation independently of p27 cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor downregulation. PloS one. 2012;7:e41330. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao T, Furnari F, Newton AC. PHLPP: a phosphatase that directly dephosphorylates Akt, promotes apoptosis, and suppresses tumor growth. Molecular cell. 2005;18:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.