Abstract

Introduction

The current study investigated the relationship between beta-amyloid (Aβ) and cognition in a late middle-aged cohort at risk for Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Methods

184 participants (mean age=60; 72% parental history of AD) completed a [C-11]PiB positron emission tomography scan and serial cognitive evaluations. A global measure of Aβ burden was calculated, and composite scores assessing learning, delayed memory, and executive functioning were computed.

Results

Higher Aβ was associated with classification of psychometric mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at follow-up (p < .01). Linear mixed-effects regression results indicated higher Aβ was associated with greater rates of decline in delayed memory (p < .01) and executive functioning (p < .05). APOE ε4 status moderated the relationship between Aβ and cognitive trajectories (p's < .01).

Discussion

In individuals at risk for AD, greater Aβ in late middle-age is associated with increased likelihood of MCI at follow-up and steeper rates of cognitive decline.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, amyloid imaging, preclinical Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, cognition, APOE

1. Background

Beta-amyloid (Aβ) deposition is hypothesized to occur early in the development of Alzheimer's disease (AD), possibly 15-20 years prior to a dementia diagnosis [1, 2]. The reported relationship between Aβ and cognition measured at a single assessment in cognitively healthy individuals has been inconsistent, with some studies reporting modest associations [3-8] and others demonstrating no significant relationship [9-12]. However, longitudinal studies examining a variety of cognitive domains and ranging from 6-month to 10-year intervals more consistently reveal negative relationships between Aβ and cognition [13-21]. Moreover, genetic risk for AD (possession of the apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE ε4) allele) may moderate this relationship [22-25].

Most studies have focused on the relationship between Aβ, APOE, and cognition in older adults (e.g., over age 65) at risk for AD with fewer investigations in middle age (e.g., ages 45-65). Since Aβ is hypothesized to accumulate early and then plateau [1, 26], it may be possible to detect a subtle, yet clinically meaningful, relationship between Aβ and cognitive decline in midlife while Aβ is accumulating and cognition begins declining. Higher Aβ in middle age may also provide earlier prediction of disease progression. The objective of this study was to examine whether Aβ is associated with longitudinal cognitive change in a late middle-aged cohort enriched for parental history of AD (Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention (WRAP)). The first aim investigated whether Aβ is associated with classification of psychometric Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) at remote follow-up. The second aim was to determine whether Aβ is associated with longitudinal cognitive trajectories. The third aim explored whether APOE ε4 moderates the relationship between Aβ and cognitive trajectories. We hypothesized that higher Aβ would be associated with increased MCI and greater cognitive decline, and that the association between Aβ and cognitive decline would be strongest in APOE ε4 carriers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

Participants were selected from the WRAP, a late middle-aged, cognitively healthy longitudinal cohort (mean age = 53.6 years, SD = 6.6, at baseline) enriched for AD risk factors of APOE ε4 carrier status (40%) and parental history of AD (72%) [27]. The WRAP protocol includes a baseline neuropsychological evaluation (Wave 1), a second visit four years after baseline (Wave 2), and subsequent visits every two years (Waves 3-4). Because a subset of neuropsychological measures was not initiated until Wave 2, the current study design included data collected at Waves 2, 3, and 4, excluding Wave 1. Participants in the current sample (n = 184) also completed a neuroimaging procedure. The number of participants whose last visit was Wave 2, 3, or 4 was 6 (3%), 53 (29%), and 125 (68%), respectively. Of the 59 participants who had not completed Wave 4, only 2 (1%) were no longer enrolled in WRAP (1 due to dementia diagnosis, 1 deceased), and 57 remained enrolled but had not yet returned for follow-up due to the staggered enrollment of participants. The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures and each participant provided signed informed consent before participation.

2.2 Study Procedures

2.2.1 MRI and PET acquisition

All participants completed a 70-minute dynamic [C-11]Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) positron emission tomography (PET) scan on a Siemens EXACT HR+ scanner and a T1-weighted anatomical scan on a GE 3.0 Tesla MR750 (Waukesha, WI) using an 8 channel head coil, typically acquired on the same day. The neuroimaging procedure was completed on average 1.4 years (SD = 1.4) after the Wave 2 WRAP visit. Anatomical scans were reviewed by a neuroradiologist (H.A.R.) for exclusionary abnormalities. Detailed methods for [C-11]PiB radiochemical synthesis, PiB-PET scanning, and distribution volume ratio (DVR) map generation have been described previously [12, 28]. Briefly, the reconstructed PET data time series were motion corrected, denoised, and coregistered to the T1-weighted anatomical scan, and data were transformed into voxel-wise DVR images representing [C-11]PiB binding using the time activity from the cerebellum gray matter as a reference function.

Eight bilateral AD-sensitive regions-of-interest (ROIs; angular gyrus, anterior cingulate gyrus, posterior cingulate gyrus, frontal medial orbital gyrus, precuneus, supramarginal gyrus, middle temporal gyrus, and superior temporal gyrus) were selected from the automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas and were standardized and reverse warped to native space. A composite measurement of global amyloid was calculated [29], and used as the measure of Aβ.

2.2.2 Cognitive measures

Cognitive composite scores were used to reduce measurement error and potential Type I error associated with conducting multiple comparisons. Three composite scores for each of waves 2-4 were calculated by transforming raw scores to z-scores using the means and standard deviations of the current sample at each wave and averaging the z-scores for the three measures (listed below) included in each composite score.

Learning: Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) [30] total trials 1-5, Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Logical Memory subtest (WMS-R LM) [31] immediate recall, Brief Visuospatial Memory Test (BVMT-R) [32] immediate recall.

Delayed recall: RAVLT long-delay free recall, WMS-R LM delayed recall, BVMT-R delayed recall.

Executive functioning: Trail Making Test Part B (TMT B) [33] total time to completion, Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test [34] color-word interference total items completed in 120 seconds, Wechsler Abbreviated Intelligence Scale-Revised (WAIS-R) [35] Digit Symbol Coding total items completed in 90 seconds. The z-score for TMT B was reversed prior to inclusion in the composite so that higher z-scores indicated better performance for all tests.

An estimate of literacy (Wide Range Achievement Test – 3rd Edition reading subtest) was included as a covariate [36].

2.2.3 Classification of MCI and cognitively normal

Participants were classified as cognitively normal (CN) or psychometric MCI (pMCI) based on neuropsychological performances at their most recent WRAP visit (mean (SD) = 1.7 (0.8) years following PiB-PET scan). The pMCI criterion was developed to identify participants with very mild impairment who may progress to a clinical diagnosis of MCI. Specifically, participants were classified as having pMCI if performances on at least two individual tests within a cognitive domain (learning, delayed recall, executive functioning), or one test in each of the three cognitive domains, were at least 1.5 standard deviations below the mean of an internally-derived robust normative sample [37, 38]. The robust normative sample included 476 WRAP participants that remained cognitively normal throughout the duration of the study.

2.3 Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS version 22. Statistical significance was defined as p < .05 unless specified otherwise.

2.3.1 Relationship between beta-amyloid and follow-up cognitive status

A logistic regression analysis examined if Aβ predicted follow-up cognitive status at most recent visit (CN versus pMCI), controlling for covariates of age at PiB-PET scan, sex, literacy, number of years enrolled in WRAP, and interval (years) between PiB-PET scan and most recent neuropsychological evaluation.

2.3.2 Relationship among beta-amyloid and longitudinal cognitive trajectories

Linear mixed effects regression allows modeling of fixed effects (e.g., overall patterns on cognitive measures across visits) while accounting for random effects (e.g., variation associated with individual differences) and may detect decline on cognitive measures that does not exceed a specific clinical cut-off. Analyses were conducted with each cognitive composite score (learning, delayed recall, executive functioning) as an outcome variable. First, unconditional means and growth models adjusting for random effects of intercept and slope were examined for each of two covariance-variance structures (uncorrelated intercept and slope (‘variance components’) and correlation permitted between intercept and slope (‘unstructured’)). The final covariance-variance structure was selected based on model fit indices (Akaike Information Criterion). Subsequent conditional models included significant random effects plus fixed effects of sex, literacy, interval between Wave 2 cognitive evaluation and PiB-PET scan (years), Aβ (PiB DVR), time (age [centered] at each visit), and the interaction of time × Aβ. Time was operationalized as the age at each WRAP visit to provide more precise information about participants at each evaluation compared to a fixed time-structured variable. A Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons (i.e., family-wise alpha = .05 was divided by 3; .05/3 = .017 significance level used for each outcome variable).

2.3.3 Effect of APOE ε4 on the relationship between beta-amyloid and longitudinal cognitive trajectories

Similar regression models were conducted, with additional fixed effects of APOE ε4 status (ε4 carrier vs non-carrier), APOE ε4 status × time, APOE ε4 status × Aβ, and APOE ε4 status × Aβ × time included in the models. To explore the three-way interaction, follow-up simple effects analyses were conducted. Specifically, the conditional model (sex, literacy, interval, Aβ, time, time × Aβ) was conducted within ε4 carrier and non-carrier groups separately.

3. Results

3.1 Sample characteristics

Sample characteristics are displayed in Table 1. At the WRAP visit conducted nearest to the PiB-PET scan, 30 participants (16%) were classified as pMCI and 154 as CN. At the most recent WRAP visit approximately 2 years following the PiB-PET scan, 28 (15%) were classified as pMCI and 156 remained CN. Of these 28, 17 were also classified as pMCI at the WRAP visit closest to the PiB-PET scan. Mean performances on the neuropsychological measures included in composite scores are displayed in Table 2.

Table 1. Sample demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Total Sample | Cognitively Normal at follow-up | Psychometric MCI at follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 184 | 156 | 28 |

| Age | |||

| At Wave 2 study visit | 58.6 (5.8) | 58.4 (5.9) | 59.6 (5.2) |

| At PiB-PET scan | 60.3 (5.8) | 60.0 (5.9) | 61.9 (5.0) |

| Sex (F/M; %F) | 126/58 (69%) | 107/49 (69%) | 19/9 (68%) |

| Education (years) | 16.1 (2.4) | 16.1 (2.3) | 15.7 (2.5) |

| WRAT-III standard score | 106.8 (9.3) | 106.7 (9.6) | 107.7 (8.0) |

| Years enrolled in WRAP | 7.7 (1.5) | 7.6 (1.5) | 8.3 (1.6) |

| APOE ε4 allele (ε 4/non- ε4; % ε4) | 73/111 (40%) | 61/95 (39%) | 12/16 (43%) |

| Parental history of AD (+/-; %+) | 133/51 (72%) | 109/47 (70%) | 24/4 (86%) |

| Cortical PiB DVR | 1.2 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.1) | 1.3 (0.2) |

| Interval: PiB-PET & Wave 2 | 1.4 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.3) | 2.0 (1.5) |

| WRAP visit | |||

| Interval: PiB-PET & most recent | 1.7 (0.8) | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.9) |

| WRAP visit |

PiB-PET = [C-11]Pittsburgh compound B Positron Emission Tomography, WRAT-III = Wide Range Achievement Test – 3rd Edition reading subtest, PiB DVR = [C-11]Pittsburgh compound B Distribution Volume Ratio. WRAP = Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention, APOE = apolipoprotein E, AD = Alzheimer's disease

Table 2. Neuropsychological performance (mean (SD)) at each visit.

| Cognitive measure | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive Status | CN | pMCI | All | CN | pMCI | All | CN | pMCI | All | CN | pMCI | All |

| N | 156 | 28 | 184 | 156 | 28 | 184 | 150 | 28 | 178 | 106 | 19 | 125 |

| Global cognition | ||||||||||||

| MMSE | N/A | N/A | N/A | 29.4 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 29.0 | 29.3 | 29.3 | 29.1 | 29.3 |

| (0.9) | (1.0) | (0.9) | (1.0) | (1.5) | (1.1) | (1.0) | (1.8) | (1.2) | ||||

| Learning | ||||||||||||

| RAVLT Trials 1-5 Total | 51.8 | 48.4 | 51.3 | 51.2 | 46.5 | 50.5 | 52.1 | 45.4 | 51.1 | 51.7 | 45.0 | 50.7 |

| (7.9) | (8.5) | (8.1) | (8.1) | (9.6) | (8.5) | (8.3) | (7.5) | (8.6) | (7.8) | (9.1) | (8.4) | |

| WMS-R Logical Memory I | N/A | N/A | N/A | 30.7 | 25.7 | 29.9 | 30.4 | 23.5 | 29.3 | 30.0 | 23.2 | 29.0 |

| (6.0) | (6.6) | (6.3) | (5.6) | (5.8) | (6.1) | (5.6) | (4.9) | (6.0) | ||||

| BVMT-R Immediate Recall | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24.9 | 20.8 | 24.2 | 25.9 | 20.9 | 25.2 | 26.1 | 17.7 | 24.8 |

| (5.4) | (6.0) | (5.6) | (5.2) | (6.2) | (5.6) | (4.7) | (6.5) | (5.8) | ||||

| Delayed Recall | ||||||||||||

| RAVLT Long Delay Free | 10.6 | 9.4 | 10.4 | 10.7 | 8.8 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 8.3 | 10.4 | 10.9 | 8.3 | 10.5 |

| Recall | (2.7) | (3.0) | (2.8) | (2.5) | (4.2) | (2.9) | (2.7) | (3.6) | (3.0) | (2.4) | (4.0) | (2.8) |

| WMS-R Logical Memory II | N/A | N/A | N/A | 24.4 | 20.8 | 26.4 | 27.3 | 18.8 | 26.0 | 27.4 | 18.9 | 26.1 |

| (6.6) | (8.0) | (7.2) | (6.6) | (7.2) | (7.4) | (6.1) | (7.9) | (7.1) | ||||

| BVMT-R Delayed Recall | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9.7 | 8.4 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 8.1 | 9.6 | 10.2 | 7.4 | 9.8 |

| (1.8) | (2.7) | (2.0) | (1.8) | (2.5) | (2.0) | (1.5) | (2.7) | (2.0) | ||||

| Executive Functioning | ||||||||||||

| Trailmaking Test Part B | 61.0 | 69.5 | 62.3 | 58.9 | 68.1 | 60.2 | 58.7 | 71.5 | 60.7 | 60.3 | 85.4 | 64.1 |

| (18.9) | (19.5) | (19.2) | (20.1) | (20.1) | (20.3) | (17.0) | (20.0) | (18.1) | (17.5) | (22.7) | (20.4) | |

| Stroop Color-Word | 112.1 | 100.2 | 110.6 | 112.6 | 103.3 | 111.2 | 111.7 | 101.0 | 110.0 | 111.6 | 99.3 | 109.8 |

| Interference | (18.9) | (18.2) | (19.2) | (18.8) | (18.4) | (19.0) | (17.1) | (20.2) | (18.0) | (18.9) | (20.4) | (19.5) |

| WAIS-R Digit Symbol | N/A | N/A | N/A | 58.5 | 51.4 | 57.5 | 57.6 | 51.5 | 56.6 | 57.1 | 48.6 | 55.8 |

| (9.1) | (7.6) | (9.2) | (9.4) | (7.9) | (9.4) | (10.1) | (9.1) | (10.4) | ||||

CN = cognitively normal, pMCI = psychometric MCI, MMSE = Mini-Mental State Exam, RAVLT = Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test, WMS-R = Wechsler Memory Scale – Revised, BVMT-R = Brief Visuospatial Memory Test – Revised, WAIS-R = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale – Revised; Note: MMSE, WMS-R Logical Memory, BVMT-R, and WAIS-R Digit Symbol were not added to the study until Wave 2

3.2 Relationships among Aβ, AD risk factors, and cognitive status at follow-up

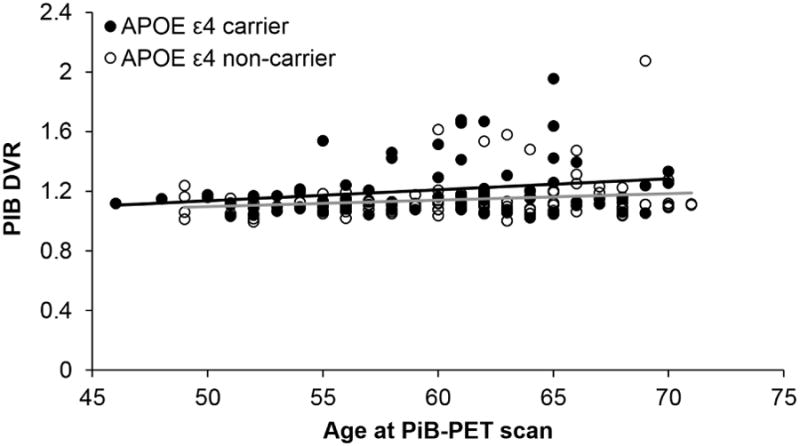

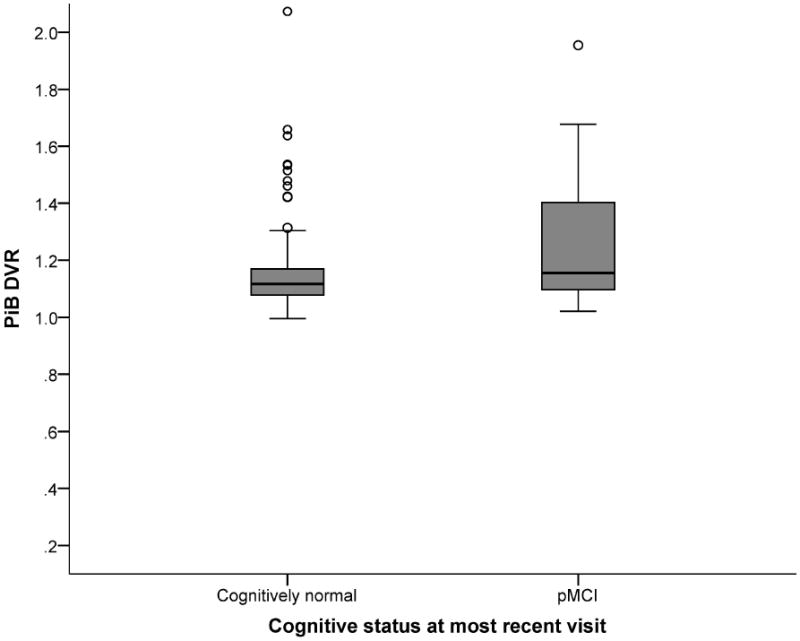

APOE ε4 carriers demonstrated significantly greater Aβ (M = 1.20) than non-carriers (M = 1.14), t(124.39) = -2.47, p < .05. Figure 1 depicts Aβ by age at PiB-PET scan for APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers. Higher Aβ was significantly associated with a greater likelihood of pMCI classification at the most recent follow-up visit, Wald X2(1) = 4.66, β = 2.64, p < .05. The full model explained 18% of the variance in cognitive status (Nagelkerke R2), and correctly classified 84.8% of cases (-2LL = 137.16, X2= 19.78, p < .01). Figure 2 displays the distribution of PiB DVR values for the CN and pMCI groups. A post-hoc analysis indicated that Aβ was not significantly associated with cognitive status at the visit closest to the PiB-PET scan, Wald X2(1) = 1.86, β=1.54, p = .17. Additional post hoc analyses included Wave 2 composite scores in addition to Aβ in the model as predictors. Results demonstrated that although the cognitive composite scores exhibited stronger relationships with cognitive status at follow-up, Aβ remained a significant contributor to follow-up cognitive status (all p's < .02).

Figure 1. Relationship between Aβ burden (PiB DVR) and age at PiB-PET scan for APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Aβ burden (PiB DVR values) for participants classified as cognitively normal or psychometric Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) at most recent cognitive evaluation.

3.3 Relationships between Aβ and longitudinal cognitive trajectories

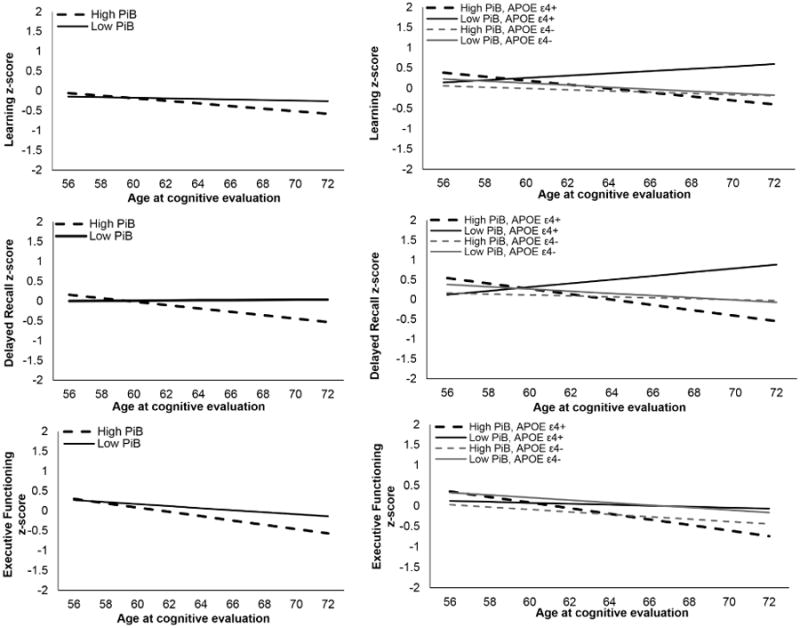

Results from linear mixed effects regression models examining the relationship between Aβ, time, and composite score at each visit are presented in Table 3. A significant interaction between time and Aβ indicated higher Aβ was associated with increased rate of decline in delayed recall performance, F(1,309.33) = 9.42, B = -.14, p = .002 (Figure 3 middle left). The interaction between time and Aβ for learning performance did not reach statistical significance, F(1,485.11) = 3.82, B = -.08, p = .051 (Figure 3 top left). A significant main effect of time indicated that as individuals progressed through the study, learning performance decreased, F(1,431.96) = 11.18, B = -.02, p = .001. A smaller, though statistically significant effect was observed for the interaction between time and Aβ for executive functioning, indicating higher Aβ was associated with increased rate of decline in executive functioning performance, F(1,444.95) = 5.87, B = -.09; p = .016 (Figure 3 bottom left).

Table 3. Parameters resulting from linear mixed effects regression models.

| Variable | Learning | Delayed Recall | Executive Functioning | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Model | B (SE) | p | 95% CI | B (SE) | p | 95% CI | B (SE) | p | 95% CI |

| Intercept | -3.49 (.54) | <.001* | -4.56, -2.43 | -3.24 (.55) | <.001* | -4.33, -2.16 | -1.70 (.58) | .004* | -2.85, -0.55 |

| Sex (Female) | 0.55 (.10) | <.001* | 0.35, 0.74 | 0.48 (.10) | <.001* | 0.28, 0.68 | 0.03 (.11) | .75 | -0.18, 0.25 |

| WRAT-III raw score | 0.06 (.01) | <.001* | 0.04, 0.08 | 0.06 (.01) | <.001* | 0.04, 0.08 | 0.04 (.11) | .001* | 0.02, 0.06 |

| Interval (years) | -0.02 (.03) | .66 | -0.08, 0.05 | -0.04 (.03) | .24 | -0.11, 0.03 | -0.01 (.04) | .85 | -0.08, 0.07 |

| Time (age centered) | -0.02 (.01) | .001* | -0.03, -0.01 | -0.02 (.01) | .01* | -0.03, -0.004 | -0.04 (.01) | <.001* | -0.05, -0.02 |

| PiB DVR | 0.45 (.44) | .31 | -0.42, 1.32 | 0.76 (.43) | .08 | -0.09, 1.60 | 0.27 (.44) | .53 | -0.59, 1.13 |

| Time × PiB DVR | -0.08 (.04) | .051 | -0.16, 0.00 | -0.14 (.04) | .002* | -0.23, -0.05 | -0.09 (.04) | .016* | -0.16, -0.02 |

| Secondary Model | |||||||||

| Intercept | -3.80 (.55) | <.001* | -4.89, -2.72 | -3.58 (.55) | <.001* | -4.67, -2.49 | -1.83 (.60) | .003 | -3.01, -0.65 |

| Sex (Female) | 0.58 (.10) | <.001* | 0.38, 0.77 | 0.51 (.10) | <.001* | 0.31, 0.71 | 0.04 (.11) | .68 | -0.17, 0.26 |

| WRAT-III raw score | 0.07 (.01) | <.001* | 0.05, 0.09 | 0.07 (.01) | <.001* | 0.05, 0.09 | 0.04 (.01) | .001* | 0.02, 0.06 |

| Interval (years) | -0.01 (.03) | .70 | -0.08, 0.05 | -0.04 (.03) | .20 | -0.11, 0.02 | -0.01 (.04) | .82 | -0.08, 0.06 |

| APOE | 0.10 (.12) | .40 | -0.14, 0.34 | 0.04 (.12) | .76 | -0.19, 0.26 | 0.08 (.13) | .52 | -0.17, 0.33 |

| Time (age centered) | -0.02 (.01) | .02 | -0.03, -0.002 | -0.02 (.01) | .07 | -0.03, 0.001 | -0.03 (.01) | <.001* | -0.04, -0.02 |

| PiB DVR | -0.59 (.71) | .41 | -1.97, 0.80 | -0.77 (.68) | .25 | -2.13, 0.56 | -0.93 (.69) | .18 | -2.29, 0.43 |

| Time × PiB DVR | 0.03 (.06) | .56 | -0.08, 0.14 | 0.05 (.06) | .45 | -0.07, 0.17 | 0.003 (.05) | .95 | -0.10, 0.10 |

| Time × APOE | 0.01 (.01) | .69 | -0.02, 0.03 | 0.01 (.01) | .35 | -0.01, 0.04 | -0.01 (.01) | .52 | -0.03, 0.02 |

| APOE × PiB DVR | 1.82 (.90) | .04 | 0.05, 3.60 | 2.80 (.87) | .001* | 1.09, 4.50 | 2.01 (.89) | .02 | 0.27, 3.75 |

| Time × APOE × PiB DVR | -0.27 (.08) | .002* | -0.43, -0.10 | -0.41 (.09) | <.001* | -0.59, -0.24 | -0.18 (.07) | .02 | -0.32, -0.03 |

WRAT-III = Wide Range Achievement Test – 3rd Edition reading subtest. Interval = Years between Wave 2 neuropsychological evaluation and PET scan. Time = age centered by mean age of sample at baseline neuropsychological evaluation (54.33). PiB DVR = [C-11]Pittsburgh compound B Distribution Volume Ratio centered by mean DVR value of sample (1.17). Outcome measures of delayed recall, learning, and executive functioning were standardized to z-scores prior to inclusion in models.

Statistically significant using Bonferroni adjusted p-value (< .017)

Figure 3.

Linear association between global PiB retention and standardized cognitive performance over time, adjusted for other predictors in models (Left). Linear association between APOE ε4 carrier status (carrier vs non-carrier), global PiB retention, and standardized cognitive performance over time, adjusted for other predictors in models (Right). High PiB was defined as 1 standard deviation above the sample mean and low PiB was defined as 1 standard deviation below the sample mean.

3.4 Effect of APOE ε4 on the relationship between Aβ and longitudinal cognitive trajectories

Results from linear mixed effects regression models examining the relationship between Aβ, time, APOE, and composite score at each visit are presented in Table 3. A significant three-way interaction among time, Aβ, and APOE was present for delayed recall, F(1,347.01) = 20.92, p < .001, and learning, F(1,473.78) = 9.97, p < .01 (Figure 3 right). The three-way interaction term neared the Bonferroni-adjusted alpha of .017 for the executive functioning composite score, F(1,423.98) = 5.56, p = .02. Simple effects analysis revealed a significant interaction between time and Aβ on delayed recall within APOE ε4 carriers, F(1,144.08) = 24.57, B = -.36, p <.001, but not within non-carriers, F(1,165.88) = 0.44, B = .04, p = .51. Similarly, a significant interaction effect was observed within APOE ε4 carriers for learning, F(1,174.82) = 12.52, B = -.23, p = .001, but was non-significant within the non-carriers, F(1,300.58) = 0.37, B = .03, p = .54.

Although PiB was included as a continuous variable, a post-hoc analysis used a median split procedure to explore potential differences between ε4 carriers and non-carriers with higher and lower Aβ levels. As depicted in Figure 3 (right), ε4 carriers with lower Aβ exhibited a lack of decline in contrast with ε4 carriers with high Aβ and non-carriers. The ε4+/low Aβ group comprised fewer participants (n=31; ε4+/high Aβ: n=42; ε4-/low Aβ: n=61; ε4-/high Aβ: n=50) and were younger than the ε4-/low Aβ group (p < .05). Moreover, the ε4+/low Aβ group comprised fewer participants that had not yet completed Wave 4 (∼50%) compared with the ε4+/high Aβ group (∼70%). With the exclusion of Wave 4 data, the interaction of time × APOE × Aβ remained statistically significant for both learning and delayed recall, suggesting group differences could not be fully explained by fewer data points in the ε4+/low Aβ group.

4. Discussion

Although AD pathology begins years before clinical symptoms emerge [39], and cognitive impairment develops several years prior to an MCI or dementia due to AD diagnosis [40], the relationship between the earliest detectable pathology and cognitive change is not well understood. Prior longitudinal studies observed that older adults with greater Aβ exhibited increased rates of cognitive decline [13-21]. The current study adds that higher Aβ in midlife in those at risk for AD is associated with steeper cognitive decline resulting in a greater incidence of progression to pMCI.

4.1 Beta-amyloid predicts follow-up classification of psychometric Mild Cognitive Impairment

Approximately 15% was classified as pMCI at the evaluation nearest the PiB-PET scan and at the most recent cognitive evaluation. While Aβ was not associated with cognitive status at the visit closest to the PiB-PET scan, higher Aβ was associated with greater likelihood of pMCI classification at approximately two-year follow-up. Although neuropsychological performance demonstrated stronger relationships with follow-up cognitive status (previously shown in [41]), Aβ remained a significant contributor to the models, suggesting it may account for variance in follow-up cognitive status not explained by cognitive performance. These results are consistent with prior studies demonstrating greater rates of progression to MCI or dementia in participants with higher Aβ. For example, one study observed that 16% of older controls with high Aβ developed MCI or dementia within 2 years, and 25% progressed within 3 years [42]. The current sample is younger (mean age = 60) than that described by Villemagne and colleagues [42] (mean age = 73), and suggests that higher Aβ predicts progression to neuropsychological impairment that may precede a clinical MCI diagnosis. However, as the construct of pMCI represents a milder form of decline, it will be necessary to document whether these individuals progress to clinical diagnoses with continued follow-up.

4.2 High beta-amyloid is associated with cognitive decline

Aβ was associated with an increased rate of decline in delayed memory and executive functioning. Results indicated a stronger relationship between Aβ and delayed memory decline compared with learning and executive functioning, consistent with prior findings [8]. Previous cross-sectional studies of Aβ and cognition in the WRAP cohort have been mixed. For example, baseline cognitive performance did not differ between groups divided into Aβ-positive, Aβ-negative, and Aβ-indeterminate [12]. Additionally, no differences in precuneus amyloid load were observed between a “stable” and “decliner” group defined by RAVLT performance [41]. However, a recent cross-sectional study demonstrated greater age-related decline in processing speed among Aβ-positive compared to Aβ-negative participants, suggesting that ‘normal’ changes in cognition that occur with aging may be accelerated in the presence of amyloid pathology [43].

The current study differed from these prior studies in quantification of Aβ (composite measure across eight ROIs examined continuously) and the longitudinal method of measuring cognition (mean slopes across four years). By examining mean slopes, while accounting for individual differences through inclusion of random effects, the current analysis attempted to detect meaningful change, even if cognitive performance fell within a “normal” range. For example, decline in cognitive performance associated with higher Aβ remained within the normal range (declines from ∼z = 0.5 to ∼z = -0.5), and average performances on cognitive measures remained within normal limits at each visit. These results of subtle cognitive decline associated with Aβ may be difficult to detect via traditional clinical methods and cross-sectional designs, and are consistent with findings in longitudinal cohorts of older adults such as Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA) [18], AIBL [20], and the Harvard Aging Brain study [17]. Our findings suggest that this Aβ-associated decline may be detected in younger ages than previously examined.

4.3 APOE ε4 moderates the relationship between beta-amyloid and cognitive decline

Similar to prior studies, APOE ε4 carriers exhibited higher Aβ than non-carriers [22, 44]. Furthermore, the presence of APOE ε4 moderated the association between Aβ and cognitive decline. Although some studies reported null effects of APOE genotype on rates of decline [20, 45], our results of a moderating effect of APOE are consistent with subsequent studies utilizing larger sample sizes and longitudinal follow-up [22-24]. The current results were driven by a significant interaction between Aβ and time within APOE ε4 carriers that was not observed within non-carriers. As displayed in Figure 3, the association between higher Aβ and time on memory performance in ε4 carriers was negative and demonstrated the steepest rate of decline. An unexpected positive association was observed between lower Aβ and time on memory performance in ε4 carriers. The latter result may be due to sampling bias, as ε4 carriers with low Aβ were less prevalent and younger than other participants, and included fewer participants that had yet to return for their fourth evaluation. However, results from a post-hoc analysis suggested that varied number of observations did not fully account for differences between ε4 carriers with high or low Aβ. It is possible that the sample size was too small to adequately investigate the interaction between Aβ and APOE, and follow-up studies on larger samples are required to replicate these findings. Interestingly, a very recent study of older adults within the AIBL cohort similarly reported unexpected findings of improved memory performance in ε4 carriers with low Aβ compared to non-carriers with low Aβ [46], which may warrant investigation of potential protective mechanisms in this group.

The mechanisms underlying the relationship between APOE ε4 and Aβ are becoming increasingly understood (see [47]). APOE ε4 carriers exhibit Aβ approximately 20 years earlier than non-carriers (e.g., age 55 compared to age 75). APOE ε4 may moderate cognitive decline and increase risk for AD by initiating and accelerating Aβ accumulation, aggregation, and clearance in the brain. APOE ε4 carriers could also be more vulnerable to Aβ-related toxicity due to Aβ-independent effects on neuronal integrity ([48]).

4.4 Limitations and future directions

The current study used a global composite measure of Aβ to summarize diffuse pathology in regions with reported increased PiB binding levels in AD; however, it is possible that regionally-specific relationships between Aβ and cognition are not captured. Furthermore, the PiB-PET scan was not acquired concurrently with the initial cognitive evaluation, complicating attempts to characterize the specific time course of Aβ development and cognitive decline. Additionally, the current study did not examine potential effects of neurofibrillary tangle pathology, neurodegeneration, or cerebrovascular disease on cognitive decline. However, incorporation of both Aβ and neuronal injury measures may provide the most accurate prognosis [49], and this is a future direction. Moreover, the sample is enriched for AD risk, and is a highly educated, mostly Caucasian sample from the Midwest region of the U.S. These results may not generalize to population-based samples of normally aging middle-aged adults.

Despite these limitations, results suggest that Aβ burden in late middle-age is associated with cognitive decline over a four-year period and predictive of pMCI diagnosis at follow-up in individuals at risk for AD. Furthermore, APOE ε4 carriers with greater Aβ may decline faster than ε4 carriers with low Aβ or non-carriers. These results suggest that identification of preclinical AD may be possible in cognitively healthy middle-aged adults with higher Aβ who may benefit most from clinical trials attempting to slow the rate of cognitive decline prior to the onset of clinical symptoms of MCI or dementia.

Research in Context.

Systematic Review

A literature review was conducted using PubMed and Web of Science databases to identify studies of beta-amyloid, PiB-PET, APOE genotype, and cognition. Although cross-sectional studies were mixed, longitudinal studies described consistent associations between greater beta-amyloid and memory decline. The majority of studies focused on elderly samples, with few on middle-aged individuals.

Interpretation

This study contributes to the literature by demonstrating that higher beta-amyloid is associated with steeper decline in delayed recall and executive functioning in a middle-aged cohort, resulting in greater progression to mild cognitive impairment. This relationship was strongest in APOE ε4 carriers.

Future directions

Research questions generated include further exploration of 1) distinct effects of beta-amyloid on cognition within APOE ε4 carriers, 2) cognitive decline on neuropsychological measures comprising composites and associated with beta-amyloid in particular brain regions, and 3) potential moderating effects of neurofibrillary tangle pathology, neurodegeneration, and cerebrovascular disease on cognition in middle age.

Acknowledgments

The project described was supported by the Clinical Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and grant UL1TR00427. Funding support was also provided by NIH grants R01 AG027161 (SCJ), R01 AG021155 (SCJ), NIA T32 AG000213 (SA), and ADRC P50 (SA). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of NIH. The authors deny any conflicts of interest related to this project. Results from this project were presented in part at the 2015 Alzheimer's Association International Conference in Washington DC on July 19, 2015. The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Janet Rowley, Amy Hawley, Kimberly Mueller, Shawn Bolin, Lisa Bluder, Diane Wilkinson, Nia Norris, Emily Groth, Allen Wenzel, Susan Schroeder, Laura Hegge, Chuck Illingworth, and researchers and staff at the UW Waisman Center for assistance in recruitment, data collection, and data analysis. Most importantly, we wish to thank our dedicated participants of the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention for their continued support and participation in this research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:207–16. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–5. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rentz DM, Locascio JJ, Becker JA, Moran EK, Eng E, Buckner RL, et al. Cognition, reserve, and amyloid deposition in normal aging. Annals of neurology. 2010;67:353–64. doi: 10.1002/ana.21904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mormino EC, Kluth JT, Madison CM, Rabinovici GD, Baker SL, Miller BL, et al. Episodic memory loss is related to hippocampal-mediated beta-amyloid deposition in elderly subjects. Brain. 2009;132:1310–23. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pike KE, Savage G, Villemagne VL, Ng S, Moss SA, Maruff P, et al. Beta-amyloid imaging and memory in non-demented individuals: evidence for preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2007;130:2837–44. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodrigue KM, Kennedy KM, Devous MD, Sr, Rieck JR, Hebrank AC, Diaz-Arrastia R, et al. beta-Amyloid burden in healthy aging: regional distribution and cognitive consequences. Neurology. 2012;78:387–95. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318245d295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sperling RA, Johnson KA, Doraiswamy PM, Reiman EM, Fleisher AS, Sabbagh MN, et al. Amyloid deposition detected with florbetapir F 18 ((18)F-AV-45) is related to lower episodic memory performance in clinically normal older individuals. Neurobiol Aging. 2013;34:822–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hedden T, Oh H, Younger AP, Patel TA. Meta-analysis of amyloid-cognition relations in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2013;80:1341–8. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828ab35d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aizenstein HJ, Nebes RD, Saxton JA, Price JC, Mathis CA, Tsopelas ND, et al. Frequent amyloid deposition without significant cognitive impairment among the elderly. Archives of neurology. 2008;65:1509–17. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marchant NL, Reed BR, DeCarli CS, Madison CM, Weiner MW, Chui HC, et al. Cerebrovascular disease, beta-amyloid, and cognition in aging. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:1006.e25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storandt M, Head D, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Morris JC. Toward a multifactorial model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2012;33:2262–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson SC, Christian BT, Okonkwo OC, Oh JM, Harding S, Xu G, et al. Amyloid burden and neural function in people at risk for Alzheimer's Disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, Rentz DM, Raman R, Thomas RG, et al. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA neurology. 2014;71:961–70. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doraiswamy PM, Sperling RA, Johnson K, Reiman EM, Wong TZ, Sabbagh MN, et al. Florbetapir F 18 amyloid PET and 36-month cognitive decline: a prospective multicenter study. Molecular psychiatry. 2014;19:1044–51. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawas CH, Greenia DE, Bullain SS, Clark CM, Pontecorvo MJ, Joshi AD, et al. Amyloid imaging and cognitive decline in nondemented oldest-old: the 90+ Study. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2013;9:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lim YY, Pietrzak RH, Ellis KA, Jaeger J, Harrington K, Ashwood T, et al. Rapid decline in episodic memory in healthy older adults with high amyloid-beta. Journal of Alzheimer's disease: JAD. 2013;33:675–9. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mormino EC, Betensky RA, Hedden T, Schultz AP, Amariglio RE, Rentz DM, et al. Synergistic effect of beta-amyloid and neurodegeneration on cognitive decline in clinically normal individuals. JAMA neurology. 2014;71:1379–85. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Resnick SM, Sojkova J, Zhou Y, An Y, Ye W, Holt DP, et al. Longitudinal cognitive decline is associated with fibrillar amyloid-beta measured by [11C]PiB. Neurology. 2010;74:807–15. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181d3e3e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storandt M, Mintun MA, Head D, Morris JC. Cognitive decline and brain volume loss as signatures of cerebral amyloid-beta peptide deposition identified with Pittsburgh compound B: cognitive decline associated with Abeta deposition. Archives of neurology. 2009;66:1476–81. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lim YY, Maruff P, Pietrzak RH, Ames D, Ellis KA, Harrington K, et al. Effect of amyloid on memory and non-memory decline from preclinical to clinical Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2014;137:221–31. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Darby D, Maruff P, Savage G, Ng S, et al. Abeta deposits in older non-demented individuals with cognitive decline are indicative of preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1688–97. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kantarci K, Lowe V, Przybelski SA, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, Ivnik RJ, et al. APOE modifies the association between Abeta load and cognition in cognitively normal older adults. Neurology. 2012;78:232–40. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31824365ab. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim YY, Ellis KA, Ames D, Darby D, Harrington K, Martins RN, et al. Abeta amyloid, cognition, and APOE genotype in healthy older adults. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2013;9:538–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mormino EC, Betensky RA, Hedden T, Schultz AP, Ward A, Huijbers W, et al. Amyloid and APOE epsilon4 interact to influence short-term decline in preclinical Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2014;82:1760–7. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim YY, Villemagne VL, Pietrzak RH, Ames D, Ellis KA, Harrington K, et al. APOE epsilon4 moderates amyloid-related memory decline in preclinical Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:1239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, et al. Amyloid beta deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer's disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:357–67. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sager MA, Hermann B, La Rue A. Middle-aged children of persons with Alzheimer's disease: APOE genotypes and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention. Journal of geriatric psychiatry and neurology. 2005;18:245–9. doi: 10.1177/0891988705281882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Racine AM, Adluru N, Alexander AL, Christian BT, Okonkwo OC, Oh J, et al. Associations between white matter microstructure and amyloid burden in preclinical Alzheimer's disease: A multimodal imaging investigation. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sprecher KE, Bendlin BB, Racine AM, Okonkwo OC, Christian BT, Koscik RL, et al. Amyloid burden is associated with self-reported sleep in nondemented late middle-aged adults. Neurobiol Aging. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt M. Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test: A Handbook. Los Angeles, California: Western Psychological Services; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler . Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised. The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, inc for Psychological Corp; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benedict RH. Brief Visuospatial Memory Test - Revised. Odessa, FL.: Psychological Assessment resources, inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reitan RM, Wolfson D. The Halstead–Reitan Neuropsychological Test Battery: Therapy and clinical interpretation. Tucson, AZ: Neuropsychological Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Trenerry MR, Crosson B, DeBoe J, Leber WR. The Stroop Neuropsychological Screening Test. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wechsler . Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale - Revised. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt brace & co for The Psychological Corporation; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wilkinson G. The Wide Range Achievement Test: Manual. Third. Wilmington, DE: Jastak Association; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clark LR, Koscik RL, Nicholas CR, Okonkwo OC, Engelman CD, Bratzke LC, et al. Mild Cognitive Impairment in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention (WRAP) study: Prevalence and characteristics using robust and standard neuropsychological normative data. under review. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acw024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koscik RL, La Rue A, Jonaitis EM, Okonkwo OC, Johnson SC, Bendlin BB, et al. Emergence of mild cognitive impairment in late middle-aged adults in the wisconsin registry for Alzheimer's prevention. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38:16–30. doi: 10.1159/000355682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, et al. Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia: the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2011;7:280–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rajan KB, Wilson RS, Weuve J, Barnes LL, Evans DA. Cognitive impairment 18 years before clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementia. Neurology. 2015 doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Okonkwo OC, Oh JM, Koscik R, Jonaitis E, Cleary CA, Dowling NM, et al. Amyloid burden, neuronal function, and cognitive decline in middle-aged adults at risk for Alzheimer's disease. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society: JINS. 2014;20:422–33. doi: 10.1017/S1355617714000113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Villemagne VL, Pike KE, Chetelat G, Ellis KA, Mulligan RS, Bourgeat P, et al. Longitudinal assessment of Abeta and cognition in aging and Alzheimer disease. Annals of neurology. 2011;69:181–92. doi: 10.1002/ana.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doherty BM, Schultz SA, Oh JM, Koscik RL, Dowling NM, Barnhart TE, et al. Amyloid burden, cortical thickness, and cognitive function in the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer's Prevention. Alzheimer's & dementia: diagnosis, assessment & disease monitoring. 2015;1:160–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Resnick SM, Bilgel M, Moghekar A, An Y, Cai Q, Wang MC, et al. Changes in Abeta biomarkers and associations with APOE genotype in 2 longitudinal cohorts. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36:2333–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ellis KA, Lim YY, Harrington K, Ames D, Bush AI, Darby D, et al. Decline in cognitive function over 18 months in healthy older adults with high amyloid-beta. Journal of Alzheimer's disease: JAD. 2013;34:861–71. doi: 10.3233/JAD-122170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thai C, Lim YY, Villemagne VL, Laws SM, Ames D, Ellis KA, et al. Amyloid-Related Memory Decline in Preclinical Alzheimer's Disease Is Dependent on APOE epsilon4 and Is Detectable over 18-Months. PloS one. 2015;10:e0139082. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu CC, Kanekiyo T, Xu H, Bu G. Apolipoprotein E and Alzheimer disease: risk, mechanisms and therapy. Nature reviews Neurology. 2013;9:106–18. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolf AB, Valla J, Bu G, Kim J, LaDu MJ, Reiman EM, et al. Apolipoprotein E as a beta-amyloid-independent factor in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's research & therapy. 2013;5:38. doi: 10.1186/alzrt204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vos SJ, Verhey F, Frolich L, Kornhuber J, Wiltfang J, Maier W, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of Alzheimer's disease at the mild cognitive impairment stage. Brain. 2015;138:1327–38. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]