Abstract

Introduction

The aim of this study was to investigate long-term trends in secondary stroke prevention through management of vascular risk factors directly before hospital admission for recurrent stroke.

Material and methods

This is a retrospective registry-based analysis of consecutive recurrent acute stroke patients from a highly urbanized area (Warsaw, Poland) admitted to a single stroke center between 1995 and 2013 with previous ischemic stroke. We compared between four consecutive time periods: 1995–1999, 2000–2004, 2005–2009 and 2010–2013.

Results

During the study period, 894 patients with recurrent strokes were admitted (18% of all strokes), including 867 with previous ischemic stroke (our study group). Among those patients, the proportion of recurrent ischemic strokes (88.1% to 93.9%) (p = 0.319) and males (44% to 49.7%) (p = 0.5) remained stable. However, there was a rising trend in patients’ age (median age of 73, 74, 76 and 77 years, respectively). There was also an increase in the use of antihypertensives (from 70.2% to 83.8%) (p = 0.013), vitamin K antagonists (from 4.8% to 15.6%) (p = 0.012) and statins (from 32.5% to 59.4%) (p < 0.001). Nonetheless, 21% of patients did not receive any antithrombotic prophylaxis. Tobacco smoking pattern remained unchanged.

Conclusions

Our data indicate a clear overall improvement of secondary stroke prevention. However, persistent use of antithrombotic drugs and tobacco smoking after the first ischemic stroke is constantly suboptimal.

Keywords: stroke, stroke register, secondary prevention, recurrent stroke

Introduction

Stroke continues to be one of the leading causes of adult disability [1]. In a meta-analysis of 13 studies. the cumulative risks of stroke recurrence after 1 month, 1 year, and 10 years were 3.1%, 11.1% and 39.2%, respectively, with the first period after the event being the most vulnerable [2]. Moreover, case fatality 30 days after the first recurrent stroke is estimated to reach 41%, which is significantly greater than the case fatality at 30 days after a first-ever stroke (22%) [2]. Primary and secondary stroke prevention play a crucial role in counteracting the morbidity and mortality related to stroke. The improved control of stroke risk factors may contribute to better prevention [3, 4]. Secondary stroke prevention guidelines have been modified in the last decades due to better knowledge of stroke risk factors and the development of pharmacological and non-pharmacological methods for their reduction [5].

Studies have reported long-term changes in the management of stroke risk factors for secondary prevention in North American and Australian populations [6, 7]. However, there are no recent data on long-term trends in secondary stroke prevention from Europe and no available reports from countries after the economic transition. Such data would provide information about adherence to guidelines for prevention of recurrent stroke and identify the most vulnerable areas that need to be improved. The aim of this study was to investigate changes in secondary stroke prevention in acute recurrent stroke patients with a previous ischemic stroke that occurred over the last two decades in a highly urbanized area of Poland.

Material and methods

Our study center has a stroke unit and provides neurological care for approximately 250 000 inhabitants of a highly urbanized area (Warsaw, Poland). We carried out a retrospective analysis of consecutive acute stroke patients with a history of previous ischemic stroke, admitted between July 1995 and December 2013. Data were prospectively collected from a detailed stroke registry [8], developed as an adaptation of the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke Data Bank protocols [9]. Collected information included: patient demographics, stroke risk factors, comorbidities, medications and routine brain imaging findings.

The diagnosis of stroke was based on clinical symptoms, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) definition and brain imaging (usually computed tomography). Stroke severity was measured with the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) [10]. The type of previous stroke and list of pre-stroke medications were determined using past medical records or the patient's (or his/her family) statement. We analyzed changes between four consecutive periods: 1995 to 1999 (period 1), 2000 to 2004 (period 2), 2005 to 2009 (period 3) and 2010 to 2013 (period 4).

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are presented as the number of valid observations and the proportion. Due to non-normal distribution, continuous variables are presented as the median with interquartile range (1st quartile and 3rd quartile, IQR). We compared the time periods (e.g. period 3 vs. period 2 and period 4 vs. period 3) and each time period with the first time period (e.g. period 4 vs. period 1) using the χ2 test and post hoc Kruskal-Wallis test. To minimize the risk of type I errors, pairwise comparisons were done only if the overall test indicated a significant difference among all four periods. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. Calculations were carried out in Statistica 10.0 (Stat Soft Inc., Tulsa, USA, 2011).

Results

Structure of the admissions

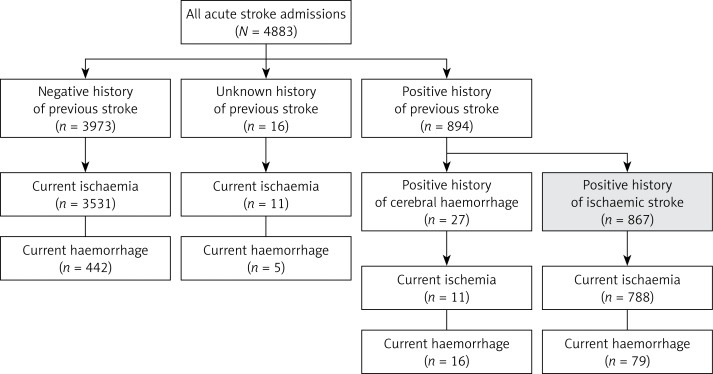

In the analyzed time periods, there were 4883 acute stroke admissions; 894 (18%) were recurrent and 867 (82.1%) were in patients who had a previous ischemic stroke (Figure 1). The proportion of recurrent strokes in patients with a history of ischemic stroke did not change during the study periods 1–4 (17%, 17.9%, 17.6% and 17.8%, respectively). Recurrent strokes in patients with a history of ischemic stroke were mostly ischemic, and this did not change during the study period.

Figure 1.

Acute stroke admissions in years 1995–2013

General characteristics

The median age at admission increased (from 73 to 77 years; p = 0.022) with time, and the baseline neurological deficit fluctuated, with a general strong trend towards less severe strokes (Table I). There was a tendency towards an increasing proportion of patients with preexisting hypertension (from 80.8% to 88.5%). The distribution of other vascular risk factors (i.e. atrial fibrillation, diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease and smoking) remained stable over the years. The proportion of patients with cholesterol levels < 200 mg/dl and low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) < 75 mg/l increased from 2005–2010 (Table I).

Table I.

Clinical characteristics of 867 recurrent stroke patients with previous ischemic stroke admitted from 1995–2013

| Parameter | Years 1995–1999 | Years 2000–2004 | Years 2005–2009 | Years 2010–2013 | Overall p |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | ||

| General information: | |||||||||

| Male gender, n (%) | 109 | 48 (44.0) | 274 | 139 (50.7) | 289 | 132 (45.7) | 195 | 97 (49.7) | 0.500 |

| Age, median (IQR) [years] | 109 | 73 (65–83) | 274 | 74 (66–80) | 289 | 76 (67–83) | 195 | 77 (69–83) | 0.022 |

| Patients aged < 55 years, n (%) | 109 | 11 (10.1) | 274 | 21 (7.6) | 289 | 17 (5.9) | 195 | 7 (3.6) | 0.119 |

| Patients aged ≥ 80 years, n (%) | 109 | 36 (33.0) | 274 | 73 (26.6) | 289 | 102 (35.3) | 195 | 73 (37.4) | 0.059 |

| Ischemic stroke, n (%) | 109 | 96 (88.1) | 274 | 246 (89.8) | 289 | 263 (91.0) | 195 | 183 (93.9) | 0.319 |

| Baseline NIHSS, median (IQR) | 109 | 13 (7–22) | 245 | 14 (7–21) | 230 | 10 (5–19)a,b | 194 | 8 (4–17)a | < 0.001 |

| Vascular risk factors: | |||||||||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 104 | 84 (80.8) | 272 | 223 (82.0) | 282 | 248 (87.9) | 191 | 169 (88.5) | 0.066 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 104 | 29 (27.9) | 270 | 83 (30.7) | 285 | 104 (36.5) | 192 | 68 (35.4) | 0.277 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 109 | 33 (30.3) | 274 | 73 (26.6) | 289 | 84 (29.1) | 195 | 57 (29.2) | 0.866 |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 104 | 29 (27.9) | 268 | 79 (29.5) | 283 | 88 (31.1) | 187 | 54 (28.9) | 0.920 |

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 104 | 40 (38.5) | 270 | 117 (43.3) | 271 | 116 (42.8) | 189 | 69 (36.5) | 0.419 |

| Myocardial infarction in past, n (%) | 104 | 26 (25.0) | 269 | 50 (18.6) | 286 | 54 (18.9) | 193 | 41 (21.2) | 0.501 |

| Tobacco smoking, n (%): | |||||||||

| Current | 102 | 17 (16.7) | 267 | 58 (21.7) | 281 | 56 (19.9) | 185 | 34 (18.4) | 0.282 |

| Previous | 14 (13.7) | 52 (19.5) | 60 (21.4) | 46 (24.9) | |||||

| Never | 71 (69.6) | 157 (58.8) | 165 (58.7) | 105 (56.7) | |||||

| Total cholesterol, median (IQR) | 96 | 200 (173–236) | 226 | 201 (173–229) | 261 | 179 (151–215)a,b | 184 | 164 (141–202)a | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 200 mg/dl, n (%) | 49 (51.0) | 111 (49.1) | 176 (67.4)a,b | 137 (74.5)a | < 0.001 | ||||

| LDL cholesterol | 78 | 131 (110–154) | 222 | 131 (108–159) | 260 | 111 (85–140a,b | 177 | 96 (72–127)a,b | < 0.001 |

| ≤ 75 mg/dl, n (%) | 6 (7.7) | 11 (5.0) | 45 (17.3)a,b | 52 (29.4)a,b | < 0.001 | ||||

Significant difference compared with the 1995–1999 period

significant difference compared with the preceding period

IQR – interquartile range, LDL – low density lipoprotein.

Pre-stroke treatment

The pre-stroke use of antihypertensives increased significantly in patients from years 1995–1999 (70.2%) until years 2005–2009 (80.4%) and then remained stable. This was also found for the subgroup of patients diagnosed with hypertension. The use of vitamin K antagonists increased significantly, from 4.8% in 1995–1999 to 15.6% in 2010–2013, in patients with a similar tendency in the subgroup with pre-existing atrial fibrillation (AF). The use of antiplatelet drugs (mostly aspirin) did not change significantly. A consistent increase of statin use was observed after 2000 (Table II).

Table II.

Changes in pre-stroke medications in recurrent stroke patients in the analyzed periods

| Pre-stroke medications | Years 1995–1999 | Years 2000–2004 | Years 2005–2009 | Years 2010–2013 | Overall p |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | N | Value | ||

| Antihypertensives, n (%) | 104 | 73 (70.2) | 269 | 199 (74.0) | 285 | 229 (80.4)a | 191 | 160 (83.8)a | 0.013 |

| In patients with preexisting HTN, n (%) | 83 | 73 (88.0) | 220 | 194 (88.2) | 245 | 218 (89.0) | 168 | 151 (89.9) | 0.950 |

| Antiplatelets, n (%) | 105 | 52 (49.5) | 269 | 146 (54.3) | 278 | 168 (60.4) | 186 | 118 (63.4)a | 0.057 |

| Vitamin K antagonists, n (%) | 105 | 5 (4.8) | 268 | 24 (9.0) | 283 | 39 (13.8)a | 186 | 29 (15.6)a | 0.012 |

| In patients with preexisting AF, n (%) | 28 | 4 (14.3) | 81 | 15 (18.5) | 102 | 27 (26.5) | 66 | 19 (28.8) | 0.265 |

| Statins, n (%) | – | – | 123 | 40 (32.5) | 273 | 106 (38.8) | 187 | 111 (59.4)b | < 0.001 |

Significant difference compared with period 1995–1999

significant difference compared with preceding time period

AF – atrial fibrillation.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study from Central and Eastern Europe that has directly investigated long-term trends in the management of vascular risk factors in acute stroke patients with a history of previous ischemic stroke. Over the years, recurrent stroke patients tended to be older, but with a tendency towards decreased severity of neurological deficits. This finding is consistent with other long-term observations [11], and, in combination with the stable proportion of recurrent strokes, it indirectly confirms the increasing effectiveness of secondary prevention efforts for ischemic stroke.

The management of stroke risk factors contributed to better prevention of secondary strokes. The pattern of improved hypertension control has been demonstrated in high-income countries, which have experienced a 42% decrease in the overall stroke incidence during the past 40 years [12]. The increasing detection of hypertension and rising use of antihypertensives observed in our study are consistent with other registries [11, 13–15]. In our registry the proportion of patients with other vascular risk factors (congestive heart failure, coronary artery disease and post-myocardial infarction) did not change significantly, which was consistent with other registries [11, 14]. Carrera et al. [14] reported an increase in incidence of diabetes and hyperglycemia in a 25-year observation period of acute stroke admissions, which was not confirmed in our study, but also Girot et al. [13] observed a stable proportion of diabetes in their study group. The proportion of patients receiving vitamin K antagonists and those with atrial fibrillation also increased, in concordance with other registers [11, 15–18]. Interestingly, increased use of anticoagulants did not affect the number of recurrent hemorrhagic strokes. Unfortunately this phenomenon can be to a large extent explained by the fact of their subtherapeutic use. This may be at least partly explained by a high proportion of patients with a non-therapeutic International Normalized Ratio [19]. We have addressed it in another study [19]. The increasing use of statins corresponded to lower cholesterol levels in our study group, which is consistent with other European registries [15, 16].

The usefulness of platelet-inhibiting drugs in stroke prevention was first reviewed by meta-analysis in 1988, and their use was justified [20]. The prescription rate of antiplatelet agents in our study group did not change significantly over the years. It is noteworthy that 21% of patients with recurrent stroke still were not treated with antiplatelet agents or anticoagulants. This finding may result from poor compliance and persistence, as was described in other populations [21]. As reported previously, the 3 month to 1 year adherence to medications prescribed for secondary stroke prevention is about 65% [22, 23], and this may not be improved even by additional interventions such as motivational interviewing [24]. In addition, the proportion of smokers did not change significantly, in concordance with observations from other European countries [13, 25].

Our study has limitations. It is based on a registry from a single urban stroke center; thus, the results may not be fully representative of the whole country. We also did not have exact data about the time that passed between the index stroke and the preceding ischemic event.

In conclusion, our findings demonstrated that the management of vascular risk factors, over the last two decades, in urban Polish patients with recurrent stroke has substantially improved according to evolving guidelines, including increased use of antihypertensives, vitamin K antagonists and statins. It is noteworthy that we also observed a similar tendency in improving primary stroke prevention [26]. The use of statins in secondary stroke prevention is not only beneficial due to the lipid-lowering effect but also because of a significant role in reduction of platelet activation and reactivity [27]. Of note, their use is also beneficial in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis [28]. The use of statins raised concern in previously published studies that noted an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in patients receiving a statin [29–31]. However, two other meta-analyses of studies did not confirm increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in patients receiving statins [32, 33]. Moreover, new evidence suggests that statins taken prior to or continued during admission for intracerebral hemorrhage may be even associated with positive outcomes [29]. However, there is much to be improved, as smoking patterns remained unchanged, and 1 in 5 patients still did not take any antiplatelet or anticoagulant treatment. One potential solution to improve patient adherence to evidence-based treatment is to continue extended neurological follow-up. Another important issue is the proper diagnostics and treatment of vascular risk factors by neurologists and primary care physicians, who need to be more aware of secondary stroke prevention efforts.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2–220. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31823ac046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohan KM, Wolfe CD, Rudd AG, et al. Risk and cumulative risk of stroke recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Stroke. 2011;42:1489–94. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.602615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45:2160–236. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Legge S, Koch G, Diomedi M, et al. Stroke prevention: managing modifiable risk factors. Stroke Res Treat. 2012;2012:391538. doi: 10.1155/2012/391538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong KS, Yegiaian S, Lee M, et al. Declining stroke and vascular event recurrence rates in secondary prevention trials over the past 50 years and consequences for current trial design. Circulation. 2011;123:2111–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.934786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sciacca RR, Rundek T, Sacco RL, et al. Recurrent stroke and cardiac risks after first ischemic stroke: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology. 2006;66:641–6. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000201253.93811.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sluggett JK, Caughey GE, Ward MB, et al. Use of secondary stroke prevention medicines in Australia: national trends, 2003-2009. Med J Aust. 2014;201:54–7. doi: 10.5694/mja13.00186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czlonkowska A, Ryglewicz D, Weissbein T, et al. A prospective community based study of stroke in Warsaw, Poland. Stroke. 1994;25:547–51. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.3.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foulkes MA, Wolf PA, Price TR, et al. The Stroke Data Bank: design, methods, and baseline characteristics. Stroke. 1988;19:547–54. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.5.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brott TG, Adams HP, Olinger CP, et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: a clinical examination scale. Stroke. 1989;20:864–70. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.7.864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teusch Y, Brainin M, Matz K, et al. Austrian Stroke Unit Registry Collaborators. Time trends in patient characteristics treated on acute stroke-units: results from the Austrian Stroke Unit Registry 2003-2011. Stroke. 2013;44:1070–4. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.676114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feigin VL, Lawes CM, Bennett DA, et al. Worldwide stroke incidence and early case fatality reported in 56 population-based studies: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:355–69. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70025-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Girot M, Mackowiak-Cordoliani MA, Deplanque D, et al. Secondary prevention after ischemic stroke. Evolution over time in practice. J Neurol. 2005;252:14–20. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0591-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrera E, Maeder-Ingvar M, Rossetti AO, et al. Lausanne Stroke Registry. Trends in risk factors, patterns and causes in hospitalized strokes over 25 years: The Lausanne Stroke Registry. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;24:97–103. doi: 10.1159/000103123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Appelros P, Jonsson F, Åsberg S, et al. Riks-Stroke Collaboration. Trends in stroke treatment and outcome between 1995 and 2010: observations from Riks-Stroke, the Swedish stroke register. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;37:22–9. doi: 10.1159/000356346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Canavero I, Cavallini A, Perrone P, et al. Lombardia Stroke Registry (LSR) investigators. Clinical factors associated with statins prescription in acute ischemic stroke patients: findings from the Lombardia Stroke Registry. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:53. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-14-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gu Q, Paulose-Ram R, Burt VL, et al. Prescription cholesterol-lowering medication use in adults aged 40 and over: United States, 2003-2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;177:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friberg J, Gislason GH, Gadsbøll N, et al. Temporal trends in the prescription of vitamin K antagonists in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Intern Med. 2006;259:173–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bembenek JP, Karliński M, Kobayashi A, et al. The prestroke use of vitamin K antagonists for atrial fibrillation – trends over 15 years. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69:180–5. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Secondary prevention of vascular disease by prolonged antiplatelet treatment. BMJ. 1988;296:320–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tentschert S, Parigger S, Dorda V, et al. Vienna Stroke Study Group. Recurrent vascular events in patients with ischemic stroke/TIA and atrial fibrillation in relation to secondary prevention at hospital discharge. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2004;116:834–8. doi: 10.1007/s00508-004-0259-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ji R, Liu G, Shen H, et al. Persistence of secondary prevention medications after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack in Chinese population: data from China National Stroke Registry. Neurol Res. 2013;35:29–36. doi: 10.1179/1743132812Y.0000000107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bushnell CD, Olson DM, Zhao X, et al. AVAIL Investigators Secondary preventive medication persistence and adherence 1 year after stroke. Neurology. 2011;77:1182–90. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822f0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hedegaard U, Kjeldsen LJ, Pottegård A, et al. Multifaceted intervention including motivational interviewing to support medication adherence after stroke/transient ischemic attack: a randomized trial. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra. 2014;4:221–34. doi: 10.1159/000369380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Béjot Y, Daubail B, Jacquin A, et al. Trends in the incidence of ischaemic stroke in young adults between 1985 and 2011: the Dijon Stroke Registry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:509–13. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bembenek JP, Karlinski M, Mendel TA, et al. Temporal trends in vascular risk factors and etiology of urban Polish stroke patients from 1995 to 2013. J Neurol Sci. 2015;357:126–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pawelczyk M, Chmielewski H, Kaczorowska B, et al. The influence of statin therapy on platelet activity markers in hyperlipidemic patients after ischemic stroke. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:115–21. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2015.49216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Giannopoulos A, Kakkos S, Abbott A, et al. Long-term mortality in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis: implications for statin therapy. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2015;50:573–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2015.06.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sikora Newsome A, Casciere BC, Jordan JD, et al. The role of statin therapy in hemorrhagic stroke. Pharmacotherapy. 2015;35:1152–63. doi: 10.1002/phar.1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein LB, Amarenco P, Szarek M, et al. Hemorrhagic stroke in the stroke prevention by aggressive reduction in cholesterol levels study. Neurology. 2008;70:2364–70. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000296277.63350.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A, 3rd, et al. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:549–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67394-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amarenco P, Labreuche J, Lavallee P, Touboul PJ. Statins in stroke prevention and carotid atherosclerosis: systematic review and up-to-date meta-analysis. Stroke. 2004;35:2902–9. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147965.52712.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]