Intravascular near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), which has been used in over 5,000 patients to identify the lipid-core plaques (LCP) that cause coronary events, may also assist in the characterization of the carotid atherosclerotic lesions predisposing to stroke. To our knowledge, this is the first report of the use of NIRS in a patient undergoing carotid artery stenting (CAS).

In the coronary arteries NIRS seems to be capable of firstly assisting with coronary interventions by predicting distal embolization and stent failure and possibly also to identify lesions at higher risk of causing spontaneous coronary events [1–9]. While NIRS has been cleared by the FDA for detection of LCP in the coronary arteries, it has not been validated or approved for use in carotid arteries [10]. A multimodality catheter (TVC System, Infraredx, Inc, Burlington, MA) that contains intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) and NIRS was used in this carotid case.

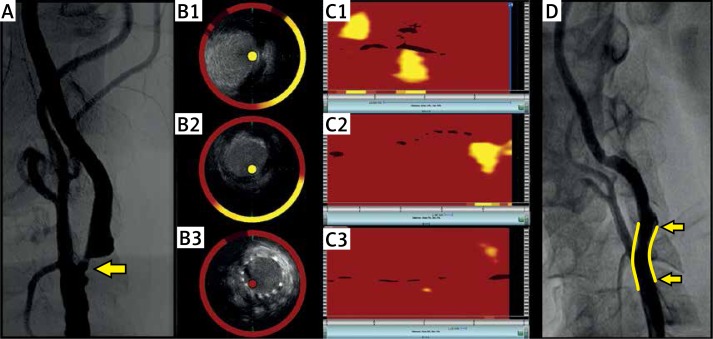

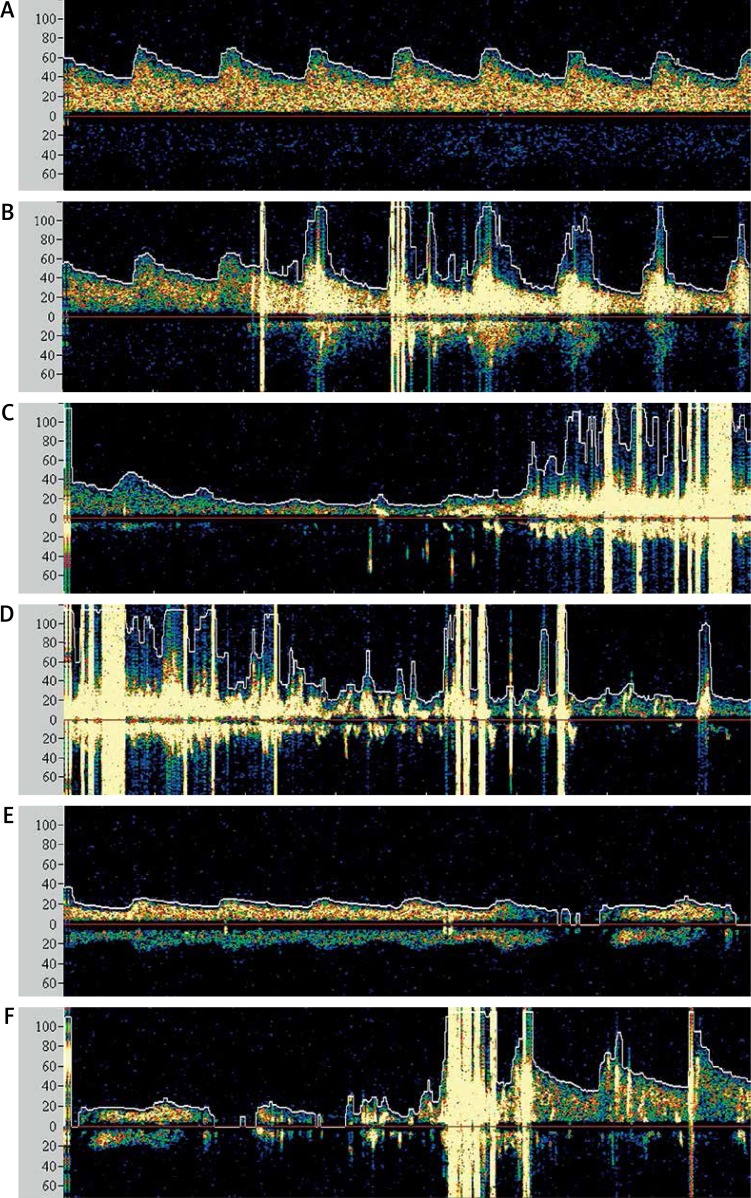

The NIRS-IVUS imaging was performed in a 62-year-old man with a history of coronary stent placement. Angiography demonstrated an occlusion of the right carotid artery and an asymptomatic 90% stenosis of the left carotid artery for which stenting was indicated (Figure 1 A). The carotid stenting was performed according to the common practice in our center [11]. A distal filter protection device (Emboshield NAV6, Abbott, Santa Clara, CA) was placed in the left carotid. As shown in Figure 2, NIRS detected two LCP. The first lipid core disappeared after a self-expandable 6/9X40 mm stent (sinus-Carotid-RX, OptiMed-Medizinische Instrumente GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) was deployed. Subsequently, post-dilation of the lesion was performed with a 5/14 mm balloon (Falcon grande, INVATEC, Roncadelle, Italy) with 8 atm. The second LCP disappeared after the post-dilation. The filter filled with material which presumably embolized during the dilation of the LCP (Figure 2). The patient experienced a slight transient decline in consciousness, but returned to normal mentation immediately after the protection filter was removed. Transcranial Doppler monitoring indicated that some of the semi-liquid lipid debris embolized to the brain despite the use of the filter, and documented a decline in the middle cerebral artery flow during the procedure and its restoration to normal levels immediately after filter removal (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

The angiogram of the left carotid artery revealed a 90% stenosis for which stenting was indicated (A). The spectroscopic image obtained prior to the intervention revealed two distinct lipid cores located proximally and distally to the critical 90% stenosis of the left internal carotid artery (C1). The corresponding IVUS image is provided (B1). The lipid cores disappeared after stent deployment (C2) and subsequent post-dilation of the lesion (panel C3). The corresponding IVUS images can be seen in panels B2 and B3. Final carotid angiography confirmed a good result (D). The stented area is marked in yellow

Figure 2.

The filter protection device with debris that presumably embolized during dilation of the lipid-core areas

Figure 3.

Transcranial Doppler ultrasound (TCD) results from the ipsilateral left middle cerebral artery (MCA). Prior to the intervention there was normal arterial flow in the left MCA (A). Five embolic showers were observed after the stent was deployed (B). The blood flow decreased during the post-dilation of the lesion (C). Seven embolic showers were observed immediately after the post-dilation (C, D). This suggests that the distal filter device might not have provided complete protection from emboli. The flow in the left MCA remained reduced after the post-dilation, which very likely occurred when the protection filter became obstructed by the embolized debris (E). The arterial flow in the left MCA subsequently returned to normal immediately after the distal protection filter was removed (F)

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of the use of NIRS during CAS. We believe that detection of emboli-prone carotid plaques by NIRS prior to a procedure may improve risk stratification and thereby assist in the selection of CAS versus carotid endarterectomy – a choice that often depends on the relative risks of the two procedures [12, 13]. Knowledge of LCP location may assist in placement of stents, and choice of a distal or proximal protection device [14]. It is important to note that NIRS is validated only for use in coronary arteries [10]. This case report provides the first clinical experience with NIRS in carotids. A validation study is needed before use of NIRS in common clinical practice. Finally, research is required to determine whether vulnerable, non-stenotic, carotid LCP could be detected by NIRS or other methods and treated in advance to prevent strokes [15].

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Madder RD, Stone GW, Erlinge D, Muller JE. The search for vulnerable plaque – the pace quickens. J Invasive Cardiol. 2013;25:29–33A. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raghunathan D, Abdel-Karim AR, Papayannis AC, et al. Relation between the presence and extent of coronary lipid core plaques detected by near-infrared spectroscopy with postpercutaneous coronary intervention myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1613–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein JA, Maini B, Dixon SR, et al. Detection of lipid-core plaques by intracoronary near-infrared spectroscopy identifies high risk of periprocedural myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:429–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.963264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstein JA, Grines C, Fischell T, et al. Coronary embolization following balloon dilation of lipid-core plaques. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2009;2:1420–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saeed B, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Slow flow after stenting of a coronary lesion with a large lipid core plaque detected by near-infrared spectroscopy. EuroIntervention. 2010;6:545. doi: 10.4244/EIJ30V6I4A90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dixon SR, Grines CL, Munir A, et al. Analysis of target lesion length before coronary artery stenting using angiography and near-infrared spectroscopy versus angiography alone. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109:60–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Madder RD, Smith JL, Dixon SR, Goldstein JA. Composition of target lesions by near-infrared spectroscopy in patients with acute coronary syndrome versus stable angina. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:55–61. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.963934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Madder RD, Goldstein JA, Madden SP, et al. Detection by near-infrared spectroscopy of large lipid core plaques at culprit sites in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2013;6:838–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2013.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oemrawsingh RM, Cheby JM, Garcia-Garcia HM, et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy predicts cardiovascular outcome in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2014;64:2510–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gardner CM, Tan H, Hull EL, et al. Detection of lipid core coronary plaques in autopsy specimens with a novel catheter-based near-infrared spectroscopy system. J Am Coll Cardiol Interv. 2008;1:638–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Veselka J, Zimolová P, Martinkovičová L, et al. Comparison of mid-term outcomes of carotid artery stenting for moderate versus critical stenosis. Arch Med Sci. 2012;8:75–80. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2012.27285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brott TG, Hobson RW, 2nd, Howard G, et al. Stenting versus endarterectomy for treatment of carotid-artery stenosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:11–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Špaček M, Veselka J. Carotid artery stenting – current status of the procedure. Arch Med Sci. 2013;9:1028–34. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2013.39216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goldstein JA, Maini B, Dixon SR, et al. Detection of lipid-core plaques by intra-coronary near-infrared spectroscopy identifies high risk of peri-procedural myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4:429–37. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.111.963264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuan C, Polissar NL, Hatsukami TS. What will noninvasive carotid atherosclerosis imaging show us about high-risk coronary plaques? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:423–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]