Abstract

Objective

This study examined whether the presence of peripheral sensory neuropathy or cardiac autonomic deficits is associated with postocclusive reactive hyperemia (reflective of microvascular function) in the diabetic foot.

Research design and methods

99 participants with type 2 diabetes were recruited into this cross-sectional study. The presence of peripheral sensory neuropathy was determined with standard clinical tests and cardiac autonomic function was assessed with heart rate variation testing. Postocclusive reactive hyperemia was measured with laser Doppler in the hallux. Multiple hierarchical regression was performed to examine relationships between neuropathy and the peak perfusion following occlusion and the time to reach this peak.

Results

Peripheral sensory neuropathy predicted 22% of the variance in time to peak following occlusion (p<0.05), being associated with a slower time to peak but was not associated with the magnitude of the peak. Heart rate variation was not associated with the postocclusive reactive hyperemia response.

Conclusions

This study found an association between the presence of peripheral sensory neuropathy in people with diabetes and altered microvascular reactivity in the lower limb.

Keywords: Neuropathy, Neuropathy and Vascular Disease, Neuropathy Complications, Microvascular

Key messages.

Peripheral sensory neuropathy in diabetes was associated with slower reactive hyperaemia response to occlusion.

Peripheral sensory neuropathy in diabetes was not associated with the peak reactive hyperaemia response to occlusion.

Cardiac autonomic neuropathy was not associated with reactive hyperaemia.

Introduction

Microvascular dysfunction is common in diabetes and acts as a major contributor to cardiovascular disease1 as well as lower limb complications.2 Regulation of the microvasculature is complex and relies on endothelial function, myogenic input, as well as neurological contributions.3 Dysfunction of neurological contributions may occur in those with diabetic neuropathy. In this way, diabetic neuropathy, while being a microvascular complication, may in turn affect microvascular functioning.3

In the foot, autonomic neuropathy results in a loss of sympathetic activity in peripheral blood vessels causing vasodilation and increased arterial flow.4 However, the increase in blood flow bypasses the cutaneous structures due to the opening of arteriovenous shunts, resulting in local ischemia.4 Neuropathy has also been associated with reductions in microvascular reactivity that are likely to contribute to the development of ulceration, impaired healing, and difficulty fighting infection.5 6

Capacity for vasodilation can be assessed by measuring local skin blood flow while introducing stressors such as heat and iontophoresis of chemical substances. This approximates the capacity in that individual to mount blood flow and inflammatory responses to injury5 and can also be indicative of early cardiovascular disease.7 While reduced vasodilation in response to heat and iontophoresis of acetylcholine (ACh) has been observed in the presence of diabetic neuropathy,8–10 the effect of neuropathy on postocclusive reactive hyperemia (PORH) is less explored.

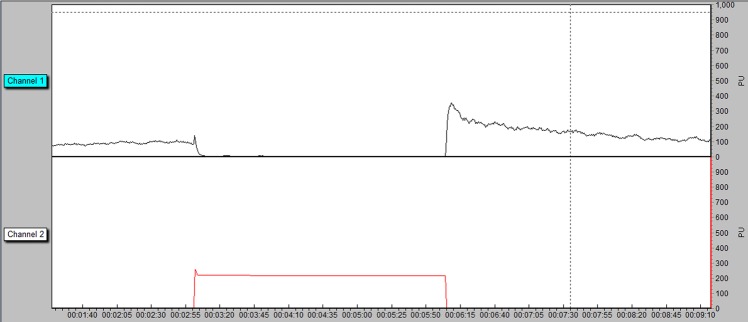

PORH is the increase in blood flow that occurs in response to a period of arterial occlusion (figure 1). Impaired PORH has been associated with diabetes11 12 and with poor blood glucose control13 and notably has been shown to precede late diabetes complications.7

Figure 1.

Typical PORH response measured in perfusion units—channel 1 and cuff pressure—channel 2. PORH, postocclusive reactive hyperemia.

The underlying mechanisms for the response are not fully understood, but it is thought that prostaglandins14 and other metabolic and endothelial dilators,15 as well as sensory nerves,16 play a role. As a relatively simple, reliable and non-invasive measure, the PORH response represents the sum of endothelial dependent and independent functions.15 If nerves are involved in the response, neuropathy may affect the PORH response. This study aimed to determine whether neuropathy in diabetes is associated with altered microvascular reactivity in the foot.

Research design and methods

Participants and procedure

A volunteer convenience sample was recruited from patients attending public and private podiatry clinics for general foot care in New South Wales, Australia, as well as those responding to poster and newspaper editorial advertising. Recruitment took place between March 2014 and January 2015. All participants were adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus and were excluded if they were pregnant, took corticosteroids, or hormone replacement therapy, had osteoporosis, chronic renal failure, current bilateral foot ulceration, neuropathic osteoarthropathy, malignancy, endocrine disorders (other than diabetes) or a recent history of foot trauma. Ethics was obtained from the University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Details of glycated hemoglobin, the presence of retinopathy and other medical history, date of diabetes diagnosis, and medication use were obtained from medical history supplied by the participant's general practitioner.

Participants refrained from nicotine, caffeine, and exercise for 2 hours and lay supine for at least 10 min prior to testing while room temperature was controlled at 23–24°C. Tests were performed in the following order: monofilament detection, vibration perception, sharp/blunt detection, and temperature detection followed by PORH and heart rate variation testing. All tests, as described below, were performed by a single podiatrist.

Sensory neuropathy assessment

The presence of large-fiber sensory neuropathy was assessed with the four-point monofilament test and vibration perception threshold (VPT)17 and small-fiber sensory neuropathy was assessed with sharp/blunt perception and temperature perception.18

A Bailey Instruments (Chorlton, Manchester, UK) 5.07 monofilament was used for the four-site monofilament test. The test was performed three times and an average of the three was taken. A score of three or less out of four sites correctly identified is indicative of large-fiber sensory loss in that foot.17 VPT was assessed with a Horwell Neurothesiometer (Scientific Laboratory Supplies, Nottingham, UK) placed on the dorsal hallux. The amplitude of the instrument was gradually increased until the participant indicated they could feel vibration. This voltage was recorded as the VPT. The mean of three readings was taken. A value of over 25 V was considered abnormal.17 Where a participant failed both tests, they were classified as having sensory neuropathy.

A Neurotip (Owen Mumford, Oxford, UK) installed in a calibrated Neuropen (Owen Mumford) was used to assess sharp/blunt perception. After demonstration of the instrument on the patient's hand, the sharp or blunt end of the instrument was placed randomly on the plantar surface of the hallux three times and the participant was asked to identify which end they perceived. This was performed three times with an average of the three being taken. A score of one or less out of three was considered abnormal. Temperature perception was assessed with a Tip-therm device (AXON GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany). The cold or warm end of the instrument was placed randomly on the dorsum of the foot and the participant was asked to identify which end they perceived. A score of one or less out of three was considered abnormal. Where participants failed both these tests, they were also classified as having sensory neuropathy.

Postocclusive reactive hyperemia

PORH was measured as described in Barwick et al.19 Briefly, measurements were made with a moorVMS-LDF2 laser Doppler module and a VHP2 digit skin heater probe and needle probe (Moor Instruments, Axminster, UK). The laser probe was fixed to the plantar surface of the participant's hallux and heated to a thermoneutral 33°C. Where access to the right hallux was precluded by injury or amputation, the left hallux was used. A 2.5 cm pneumatic cuff (Moor Instruments) was placed proximal to the probe. The following automated settings were used with the moorVMS-PRES pressure module (Moor Instruments): 3 min of baseline flux recording, inflation of the cuff to 220 mm Hg for 3 min, cuff deflation at maximum speed, and postocclusive flux recording for a further 4 min. All data were processed with moorVMS recording and analysis software V.3.1 (Moor Instruments).

The variables of peak expressed as a percentage of baseline (P%BL) and time to peak (TtP) were chosen due to their representation of the magnitude and temporal representation of the response and their established reliability.19

Cardiac autonomic function assessment

A Polar RS800cx heart monitor (Polar Electro Oy, Kempele, Finland) was used to assess heart rate variability (HRV) as a measure of cardiac autonomic function. Participants completed a supine 5 min rest recording. The R–R interval tachogram was analyzed with Kubios HRV software (V.2.1, Kuopio, 2012). Ectopic beats were removed using linear interpolation of previous and subsequent beats. Time and frequency domain parameters were assessed. Time domain measured included the SD of the N–N interval (SDNN) and the root mean square of the R–R intervals (RMS-SD). Frequency domain measures were divided by spectral power analysis into high (0.15–0.40 Hz), low (0.04–0.15 Hz), and very low-frequency (0.00–0.04 Hz) powers with total power calculated as the sum of all powers.20 Variables were left continuous due to a lack of cut-off values established to indicate pathology.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences V.22 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, USA). Reliability of sensory neuropathy diagnosis was assessed with duplicate tests on a subset of 31 participants 7–14 days apart. κ Statistics were calculated and interpreted as per Landis and Koch21 ≥0.75=excellent agreement, 0.4–0.75=fair to good agreement, and <0.40=poor agreement. Reliability of continuous measures (HRV) was assessed with duplicate tests on a subset of 29 participants 7–14 days apart. Intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated and interpreted in accordance with Portney and Watkins: >0.75=good, 0.50–0.75=moderate, and <0.50=poor.22

Several hierarchical regression models were performed to determine how much the presence of sensory neuropathy and HRV predicted the variance in PORH variables (P%BL and TtP). One model for each of the four neurological variables (presence of sensory neuropathy, RMS-SD, SDNN, and total power) was assessed. In each of the models, demographic variables identified as confounds (diabetes duration, gender, and age) were entered in level 1 and the neurological variable as the independent predictor variable in level 2. Non-normally distributed data were log transformed.

Results

Ninety-nine participants were recruited; participant characteristics are given in table 1. HRV data for three participants were unavailable leaving 96 participants for analyses of these data. TtP and P%BL were log transformed due to their non-normal distribution.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics (n=99)

| Age (mean, SD) | 68.6 (9.56) |

| Gender (male/female) | 64/35 |

| Toe pressure (mean, SD) | 99.39 (31.45) |

| HbA1c (%) (mean, SD) | 7.26 (1.47) |

| HcA1c (mmol/mol) (mean, SD) | 55.8 (16.15) |

| BMI (mean, SD) | 34 (7.42) |

| Retinopathy (past and current) (present/absent) | 7/92 |

| Sensory neuropathy (present/absent) | 41/58 |

| Diabetes duration | 11.72 (9.73) |

BMI, body mass index; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin.

The intratester reliability of the diagnosis of sensory neuropathy was excellent (large-fiber tests: left foot 1.00; right foot 0.93, small-fiber tests: left foot 0.82; right foot 0.92). The reliability of HRV was moderate for the time domains (SDNN 0.70; RMS-SD 0.66) and good for the frequency domain (total power 0.94).

Results of the hierarchical regression are found in tables 2 and 3. The presence of sensory neuropathy predicted 22% of the variance in TtP (p=0.03) with the presence of neuropathy indicating a longer latency to peak flux following release of occlusion. None of the HRV variables predicted the response.

Table 2.

Regression analyses of sensory neuropathy with PORH

| R2 change | β | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TtP | |||

| Step 1* | 0.18 | <0.01 | |

| Step 2* | 0.22 | 0.03 | |

| Duration | −0.05 | 0.60 | |

| Age | 0.05 | 0.58 | |

| Gender* | −0.44 | 0.00 | |

| Sensory neuropathy* | 0.21 | 0.03 | |

| P%BL | |||

| Step 1 | 0.03 | 0.12 | |

| Step 2 | 0.02 | 0.68 | |

| Duration | −0.16 | 0.12 | |

| Age | −0.03 | 0.76 | |

| Gender | 0.21 | 0.06 | |

| Sensory neuropathy | 0.04 | 0.41 | |

*Significant at p<0.05.

P%BL, peak as a percentage of baseline; PORH, postocclusive reactive hyperemia; TtP, time to peak.

Table 3.

Regression analyses of autonomic neuropathy variables with PORH

| R2 change | β | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TtP | |||

| Step 1* | 0.18 | <0.01 | |

| Step 2 | 0.02 | 0.15 | |

| Duration | −0.05 | 0.60 | |

| Age* | −0.41 | <0.01 | |

| Gender | 0.002 | 0.98 | |

| RMS-SD | −0.14 | 0.15 | |

| P%BL | |||

| Step 1 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| Step 2 | 0.006 | 0.45 | |

| Duration | −0.16 | 0.14 | |

| Age* | 0.22 | 0.04 | |

| Gender | −0.03 | 0.75 | |

| RMS-SD | 0.08 | 0.45 | |

| TtP | |||

| Step 1* | 0.18 | <0.01 | |

| Step 2 | 0.02 | 0.13 | |

| Duration | −0.06 | 0.56 | |

| Age* | −0.41 | <0.01 | |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.90 | |

| SDNN | −0.15 | 0.13 | |

| P%BL | |||

| Step 1 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| Step 2 | 0.005 | 0.48 | |

| Duration | −0.15 | 0.15 | |

| Age* | 0.22 | 0.04 | |

| Gender | −0.04 | 0.70 | |

| SDNN | 0.07 | 0.48 | |

| TtP | |||

| Step 1* | 0.18 | <0.01 | |

| Step 2 | 0.001 | 0.76 | |

| Duration | −0.04 | 0.67 | |

| Age* | −0.41 | <0.01 | |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.89 | |

| Total power | −0.03 | 0.76 | |

| P%BL | |||

| Step 1 | 0.06 | 0.12 | |

| Step 2 | 0.001 | 0.83 | |

| Duration | −0.16 | 0.13 | |

| Age* | 0.22 | 0.04 | |

| Gender | −0.04 | 0.70 | |

| Total power | 0.02 | 0.83 | |

*Significant at p<0.05.

P%BL, peak as a percentage of baseline; PORH, postocclusive reactive hyperemia; RMS-SD, root mean square of the R–R interval; SDNN, SD of the N–N interval; TtP, time to peak.

Conclusions

The relationship between diabetic neuropathy and microvascular reactivity is poorly understood. Such information is useful in the early diagnosis and management of diabetic foot complications. This study aimed to investigate relationships between clinically detectable peripheral sensory neuropathy, cardiac autonomic deficits, and the PORH response in the periphery. The presence of sensory neuropathy predicted 22% of the variance in the timing of the response but did not predict its magnitude. Heart rate variation did not predict temporal or magnitudinal aspects of the response.

These findings are in keeping with previous studies that have shown other microvascular reactivity parameters to be affected by the presence of neuropathy. The role of nerves in the blood flow response to heating and ACh iontophoresis and the effect of neuropathy on those responses are more established than in the PORH response.15 23 Numerous studies have demonstrated that in the presence of diabetic neuropathy, there is a reduction in blood flow response to heating9 10 and iontophoresis of ACh.8–10

PORH is thought to be mediated by a mix of metabolic dilators, endothelial dilators, myogenic relaxation, and sensory nerve activity.16 The work of Larkin and Williams24 and Lorenzo and Minson16 demonstrated the role of sensory nerves in PORH by showing a reduction in the response following anesthetization. This suggests that the presence of neuropathy should also reduce the response. In support of this, Yamamoto-Suganuma and Aso7 showed that a reduction in magnitude of the response is associated with slower sensory nerve conduction speed.

The observed relationship, the current study, of neuropathy with the timing of the response but not the magnitude is in contrast to these previous findings.7 The PORH response is characterized by a sharp initial peak followed by a delayed prolonged hyperemia. A previous study showed that a loss of neural responsiveness may be compensated by an increase in myogenic activity,25 which may have resulted in maintenance of the peak in the current study. A large proportion of the participants in this study had clinically detectable neuropathy suggesting a more advanced state of the condition. It is unknown if increases in myogenic activity remain in the presence of advanced neuropathy, and therefore, such a relationship cannot be assumed in this instance. Alternatively, the lack of association with the peak may be due to the inability of the clinical testing methods to detect early stages of neuropathy.

The diagnosis of sensory neuropathy in the current study was based on unsophisticated clinical testing, which may explain the small size of the relationship found with TtP perfusion and the fact that there was no association with the peak itself. These measures were chosen to investigate whether identification of neuropathy with non-invasive clinical tests can give information on the microvascular status of individuals.

Another limitation of the current study was the outcomes used to quantify the PORH response. Other parameters of the PORH response such as curve morphology26 or an index of the area under the curve postocclusion to preocclusion7 may also be useful indicators of disease states. Furthermore, the physiological significance of a delayed PORH response as observed in the current study and whether it is indicative of pathology is unknown, limiting interpretation of the result.

Since macrovascular disease is likely to affect microvascular function, it may affect the PORH response. Those with peripheral vascular disease were not excluded from participation in the current study, which may have affected the results. However, resting toe pressures of participants were <50 mm Hg in only 3 of the 99 participants, so severe peripheral arterial disease is not likely to have influenced the results. Evidence of other microvascular disease (retinopathy) was obtained from medical history and strict classification was not applied to diagnosis. Given the high prevalence of neuropathy in the study cohort, it is likely that the incidence of retinopathy was higher than that reported in this study. In addition to these concerns, other factors to consider in future research include the influence of edema and factors affecting blood viscosity on the PORH response.

A major consideration in this work is that it is unclear to what extent the PORH response is reflective of the microvascular disease that causes neuropathy. Although diabetes-induced alterations in vascular and metabolic pathways are implicated in the pathogenesis of neuropathy, the disease is considered a microvascular complication of diabetes due to the predominance of the ischemic pathway.3 Endoneural blood vessels display cell hyperplasia and capillary basement membrane thickening27 causing hypoperfusion and ischemia to the nerves, predominating in the lower limbs.28 These changes also occur to the cutaneous microvasculature.28 Owing to the cross-sectional nature of the current study, the extent to which neuropathy caused the observed changes to PORH or microvascular disease affected the changes to PORH and neuropathy cannot be determined.

The literature, however, is suggestive of a contribution of nerve function to reduced microvascular reactivity, independent of microvascular disease. Arora et al8 found that the reductions in the response to heating and iontophoresis of ACh seen in those with neuropathy were not concurrent with changes to sodium nitroprusside (which does not stimulate nerve fibers). This was confirmed by Caselli et al.29 Furthermore, the temporal relationships between microvascular disease and diabetic neuropathy have recently been under dispute.30 There is likely to be a cycle present whereby microvascular disease contributes to neuropathy, which contributes to further microvascular dysfunction.3

Microvascular and neural complications of diabetes are major contributors to lower limb pathology in diabetes. The impact of diabetic neuropathy on microvascular function is complex and under-researched. This study aimed to investigate whether clinically detectable peripheral sensory neuropathy or cardiac autonomic neuropathy was indicative of a reduction in the capability for vasodilation that may be relevant in cases of ulceration and non-healing. The study found that the presence of peripheral sensory neuropathy in diabetes was associated with slower TtP dilatory response to ischemia. Future research should investigate whether this change in the PORH response is relevant for pathology as well as the causal link between neuropathy and microvascular dysfunction.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the statistical support of the Hunter Medical Research Institute. A subset of the data presented in this manuscript was published in an abstract in Supplement of the 58th volume of Diabetologia.

Footnotes

Contributors: ALB contributed to the design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis of data, and writing of the manuscript. JWT contributed to the design of the study and writing of the manuscript. XJdJ contributed to the design of the study and writing of the manuscript. JRI contributed to the acquisition of data and writing of the manuscript. VHC oversaw the project and contributed to the design of the study, analysis of data, and writing of the manuscript. All authors agree on the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by departmental funding of the Faculty of Health and Medicine from the University of Newcastle (Australia), 10.13039/501100001771.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: University of Newcastle Human Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sitia S, Tomasoni L, Atzeni F et al. From endothelial dysfunction to atherosclerosis. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:830–4. 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chao CYL, Cheing GLY. Microvascular dysfunction in diabetic foot disease and ulceration. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2009;25:604–14. 10.1002/dmrr.1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stirban A. Microvascular dysfunction in the context of diabetic neuropathy. Curr Diab Rep 2014;14:1–9. 10.1007/s11892-014-0541-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edmonds ME. The neuropathic foot in diabetes Part 1: blood flow. Diabet Med 1986;3:111–15. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1986.tb00720.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hile C, Veves A. Diabetic neuropathy and microcirculation. Curr Diab Rep 2003;3:446–51. 10.1007/s11892-003-0006-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uccioli L, Mancini L, Giordano A et al. Lower limb arterio-venous shunts, autonomic neuropathy and diabetic foot. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 1992;16:123–30. 10.1016/0168-8227(92)90083-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto-Suganuma R, Aso Y. Relationship between post-occlusive forearm skin reactive hyperaemia and vascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes—a novel index for detecting micro- and macrovascular dysfunction using laser Doppler flowmetry. Diabet Med 2009;26:83–8. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora S, Smakowski P, Frykberg RG et al. Differences in foot and forearm skin microcirculation in diabetic patients with and without neuropathy. Diabetes Care 1998;21:1339–44. 10.2337/diacare.21.8.1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veves A, Akbari CM, Primavera J et al. Endothelial dysfunction and the expression of endothelial nitric oxide synthetase in diabetic neuropathy, vascular disease, and foot ulceration. Diabetes 1998;47:457–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pfützner A, Forst T, Engelbach M et al. The influence of isolated small nerve fibre dysfunction on microvascular control in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 2001;18:489–94. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00524.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jorneskog G, Brismar K, Fagrell B. Skin capillary circulation severely impaired in toes of patients with IDDM, with and without late diabetic complications. Diabetologia 1995;38:474–80. 10.1007/BF00410286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomes MB, Matheus ASM, Tibiriçá E. Evaluation of microvascular endothelial function in patients with type 1 diabetes using laser-Doppler perfusion monitoring: which method to choose? Microvasc Res 2008;76:132–3. 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jorneskog G, Brismar K, Fagrell B. Pronounced skin capillary ischemia in the feet of diabetic patients with bad metabolic control. Diabetologia 1998;41:410–15. 10.1007/s001250050923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Binggeli C, Spieker LE, Corti R et al. Statins enhance postischemic hyperemia in the skin circulation of hypercholesterolemic patients: a monitoring test of endothelial dysfunction for clinical practice? J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:71–7. 10.1016/S0735-1097(03)00505-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cracowski JL, Minson CT, Salvat-Melis M et al. Methodological issues in the assessment of skin microvascular endothelial function in humans. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2006;27:503–8. 10.1016/j.tips.2006.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenzo S, Minson CT. Human cutaneous reactive hyperaemia: role of BKca channels and sensory nerves. J Physiol (Lond) 2007;585:295–303. 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.143867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boulton AJ, Armstrong DG, Albert SF et al. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment a report of the Task Force of the Foot Care Interest Group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1679–85. 10.2337/dc08-9021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papanas N, Papatheodorou K, Papazoglou D et al. The new indicator test (Neuropad): a valuable diagnostic tool for small-fiber impairment in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Educ 2007;33:257–66, 262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barwick A, Lanting S, Chuter V, et al. Intra-tester and inter-tester reliability of post-occlusive reactive hyperaemia measurement at the hallux. Microvasc Res 2015;99:67–71. 10.1016/j.mvr.2015.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarvainen MP, Niskanen J-P, Lipponen JA et al. Kubios HRV—heart rate variability analysis software. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 2014;113:210–20. 10.1016/j.cmpb.2013.07.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Portney LG, Watkins MP. . Foundations of clinical research. Applications to practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Health, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamdy O, Abou-Elenin K, LoGerfo FW et al. Contribution of nerve-axon reflex-related vasodilation to the total skin vasodilation in diabetic patients with and without neuropathy. Diabetes Care 2001;2001:344–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larkin SW, Williams TJ. Evidence for sensory nerve involvement in cutaneous reactive hyperemia in humans. Circ Res 1993;73:147–54. 10.1161/01.RES.73.1.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun PC, Lin HD, Jao SH et al. Thermoregulatory sudomotor dysfunction and diabetic neuropathy develop in parallel in at-risk feet. Diabet Med 2008;25:413–18. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strain WD, Chaturvedi N, Bulpitt CJ et al. Albumin excretion rate and cardiovascular risk: could the association be explained by early microvascular dysfunction? Diabetes 2005;54:1816–22. 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malik RA, Tesfaye S, Thompson SD et al. Endoneurial localisation of microvascular damage in human diabetic neuropathy. Diabetologia 1993;36:454–9. 10.1007/BF00402283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tesfaye S, Selvarajah D. Advances in the epidemiology, pathogenesis and management of diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2012;28:8–14. 10.1002/dmrr.2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caselli A, Spallone V, Marfia GA et al. Validation of the nerve axon reflex for the assessment of small nerve fibre dysfunction. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 2006;77:927–32. 10.1136/jnnp.2005.069609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petropoulos IN, Green P, Chan AWS et al. Corneal confocal microscopy detects neuropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes without retinopathy or microalbuminuria. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0123517 10.1371/journal.pone.0123517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]