Abstract

Objective

Investigators within many disciplines are using measures of well-being, but it is not always clear what they are measuring, or which instruments may best meet their objectives. The aims of this review were to: systematically identify well-being instruments, explore the variety of well-being dimensions within instruments and describe how the production of instruments has developed over time.

Design

Systematic searches, thematic analysis and narrative synthesis were undertaken.

Data sources

MEDLINE, EMBASE, EconLit, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library and CINAHL from 1993 to 2014 complemented by web searches and expert consultations through 2015.

Eligibility criteria

Instruments were selected for review if they were designed for adults (≥18 years old), generic (ie, non-disease or context specific) and available in an English version.

Results

A total of 99 measures of well-being were included, and 196 dimensions of well-being were identified within them. Dimensions clustered around 6 key thematic domains: mental well-being, social well-being, physical well-being, spiritual well-being, activities and functioning, and personal circumstances. Authors were rarely explicit about how existing theories had influenced the design of their tools; however, the 2 most referenced theories were Diener's model of subjective well-being and the WHO definition of health. The period between 1990 and 1999 produced the greatest number of newly developed well-being instruments (n=27). An illustration of the dimensions identified and the instruments that measure them is provided within a thematic framework of well-being.

Conclusions

This review provides researchers with an organised toolkit of instruments, dimensions and an accompanying glossary. The striking variability between instruments supports the need to pay close attention to what is being assessed under the umbrella of ‘well-being’ measurement.

Keywords: Well-being, Quality of life, Generic, Adults, Measures

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Compared with the largest review of the topic to date, the current review contains an additional 40 instruments, and provides an organised index of dimensions not found elsewhere in the literature.

This review provides the first quantified demonstration of how self-reported measures of well-being have developed over the past 50 years.

The aim of the review was limited to adult generic measures due to practical constraints, and as a result condition-specific instruments and tools designed for use with children and adolescents were not included.

Introduction

The importance of well-being has been widely acknowledged in the past 20 years. Increasing interdisciplinary work on the topic,1 explicit governmental interest in measuring subjective well-being (SWB),2 3 and public interest4 are evidence of this. Simultaneously, the measurement of well-being, broadly defined as ‘the quality and state of a person's life’,5 has become an area of growing prominence for academics, healthcare professionals and policymakers alike.6 7 However, despite extensive study on the topic,8 there is little available consensus in the literature on the range, contents and differences between self-report measures of well-being.

Fundamental to the challenge of measuring well-being is the extent of disagreement over its definition9 and theoretical basis.8 For example, definitions of well-being often differ by discipline, and are frequently confused with related topics such as health-related quality of life, happiness and wellness. Theories of well-being are problematic due to their vast numbers; for example, some investigators approach the topic from the perspective of basic human needs,10 while others examine the capabilities of individuals11 and multiple theories have been integrated into new hybrid approaches.12 However, relatively little attention has been paid to how these varying perspectives have influenced the development and range of well-being measurement instruments in existence.

A second challenge for a researcher interested in well-being is selecting an instrument from the large number of available options. Despite the continued development of new instruments, no universally accepted measure has emerged,13 in part because there are no agreed conceptual criteria concerning what an instrument should contain. Further, what is a priority for measuring well-being in one discipline, such as health economics, may not be a priority in another context, such as clinical psychology. Given this, a universally accepted measure of well-being may be an unrealistic goal. Regardless, new tools continue to be developed in order to reflect differing perspectives,14 changing clinical needs15 and input from newly interested disciplines, such as public health.16

Ambiguity is also caused by variability in the dimensions of well-being used between instruments. Here, dimensions are defined as the underlying aspects of well-being that authors are trying to measure, such as self-acceptance, life satisfaction or social integration.17–20 The presence of differing perspectives on the topic21 is one likely cause of this ambiguity. Although the biological, psychological, social, economic and spiritual dimensions of well-being have been acknowledged in the literature,22–24 the way in which they are operationalised as dimensions across measures of well-being is largely unstated. Thus, researchers are provided with little guidance on how and where dimensions of interest can be found within the growing number of measurement instruments available.

As with most domains of measurement, there is no agency or group that oversees and coordinates the development and organisation of well-being measures. Instruments are scattered across disciplines, inconsistently labelled, and the differences between them are unclear.18 Despite efforts by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to formalise the measurement of well-being,25 not enough exhaustive advice is provided on how researchers can effectively use the many self-report instruments that have already been developed within existing literature. Researchers aiming to measure well-being are left to select instruments based on what is familiar to them within their particular discipline, what is most often used by others or to create yet another new instrument.

Despite these issues, well-being remains a highly prioritised concept of interest. Beyond being a valuable outcome in itself,26 the explicit measurement and improvement of subjective forms of well-being has become a key policy and government objective.27 28 This is in part due to the observation that being healthy does not guarantee a person feelings of well-being,4 and the finding that ‘objective’ indicators of well-being such as income can only give a partial account of what it means to live well.2 As such, interest in self-reported forms of well-being seems both practically and empirically sensible.

Previous reviews have highlighted some of the available tools.29–31 However, not all have used systematic methods for identifying measures. Many of the reviews to date have focused on psychometric properties such as validity and reliability; however, the tools themselves are typically listed without clear analysis of how their content differs. Further, the evolution of instruments over time and their theoretical underpinnings have not been described. These issues justify this review, which aims to inform researchers and practitioners about the breadth, variety and content of available measures of well-being.

The aims of the current review were to: (1) identify measures of well-being; (2) describe the characteristics of the identified instruments; (3) describe and depict how the measurement of well-being has developed over time and (4) organise the dimensions identified into a conceptual framework, highlighting key themes of well-being, and the instruments that measure them. Dimensions were defined as the conceptual subscales that the instruments investigated covered. Themes described the overarching conceptual domains that the dimensions reflect, or fit into. Our wider objective was to provide researchers with a framework and glossary of terms to aid in the selection of well-being instruments containing the most appropriate dimensions for their purposes.

Methods

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in MEDLINE, EMBASE, EconLit, PsycINFO, Cochrane Library and CINAHL databases (see online supplementary appendix 1). ‘Systematic’ within the context of the current review refers to the fact that a specific and structured search strategy was used. Additional manual hand and web searching was undertaken through 2015 using online resources, search engines and consultations with subject matter experts. The systematic search was limited to records as far back as 1993 in order to ensure we were focusing on old and new instruments that were being used in the past 20 years. Well-being measures were identified by searching through identified publications.

bmjopen-2015-010641supp_appendix1.pdf (206.1KB, pdf)

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Instruments were included in the review if they were: (1) designed for general use, either in population studies or as generic tools across contexts; (2) designed for use in adults; (3) designed for assessing well-being, including concepts such as quality of life, happiness and wellness and (4) available in an English translation. Instruments were excluded if their primary focus was: (1) disease specific (ie, cancer or stroke-specific tools); (2) context specific (ie, pregnancy) and (3) instruments designed for children or adolescents.

Data extraction

Data extraction was undertaken by two reviewers (M-JL and AM-L). Details extracted included the name of the instrument, its acronym, authorship, date of publication, number of items and response format, theories referenced, date of initial development, and the date of the latest available version of the instrument. Details about the dimensions within each instrument as specified by the author were recorded using a similar form.

Thematic analysis

The dimensions extracted from identified instruments were organised using thematic analysis32 in order to categorise them into themes. The qualitative analysis was undertaken using NVivo V.8 (NVivo qualitative data analysis software, Version 8 [program]: QSR International Pty Ltd Australia, 2008). First, the dimensions and definitions were tabulated. Prior to the analysis, the review team (M-JL, AM-L and PD) examined the full set of dimensions and combined dimensions that were unanimously identified as being indistinguishable. After a process of familiarisation with the data, each dimension was qualitatively coded. For example, dimensions such as hearing and vision clustered around the code ‘physical senses’. Coding was undertaken by two reviewers (M-JL and AM-L) and any discrepancies that arose were solved through discussion with the third member of the review team (PD). These clusters of coded dimensions were gradually assembled into larger groupings that formed preliminary themes. Once these key themes were reviewed and amended by the review team, they were defined and named. It was anticipated that themes might overlap and that dimensions could fit within multiple themes; however, the categories provided by the technique afforded some order to the otherwise unmanageably large range of dimensions. The review team included academics with backgrounds in psychology (M-JL), economics (AM-L) and clinical medicine/public health (PD), helping to minimise disciplinary biases. Results were synthesised as a narrative review.

Results

Identification of instruments

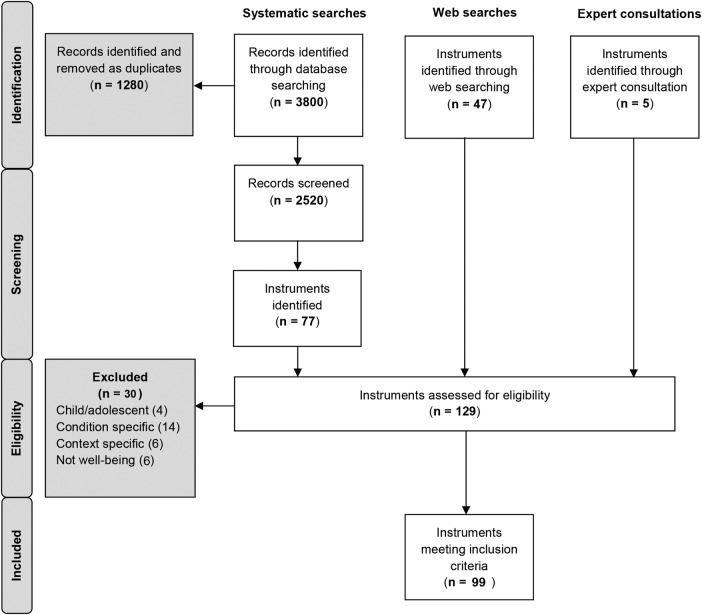

The PRISMA33 diagram summarises the search results, screening and exclusion of studies (figure 1). The systematic search provided 2520 unique records after duplicates had been removed. From the identified publications, a total of 129 instruments were assessed for eligibility, and 30 of these instruments were excluded as they were either: designed for use in children/adolescents (4/30); explicitly designed for use in specific clinical conditions (14/30); designed for specific contexts (6/30) or were deemed by the review team to not be measures of well-being (6/30). Table 1 contains details on each of the 99 instruments included in the final review. Many of the instruments have been amended and shortened from their original format; therefore, the instruments included in table 1 are either: (1) the original tools if no revised version was found or (2) the latest revised version. A breakdown of when the instruments were first developed and their most recent major revisions can be found in figure 2.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram.

Table 1.

Description of well-being tools and the themes that their dimensions reflect

| (Diagram reference number) Instrument full name | Acronym | First published | Most recent revision |

Number of items* | Themes of well-being |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global well-being | Mental well-being | Social well-being | Physical well-being | Spiritual well-being | Activities and functioning | Personal circumstances | |||||

| 1. 15D | 15D | 1981 | 198934 | 15 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 2. Affect Balance Scale | ABS | 1969 | 196935 | 10 | ● | ||||||

| 3. Affectometer 2 | A2 | 1979 | 198336 | 20 | ● | ||||||

| 4. Anamnestic Comparative Self-Assessment | ACSA | 2006 | 200637 | 1 | ● | ||||||

| 5. Arizona Integrative Outcomes Scale | AIOS | 2004 | 200438 | 1 | ● | ||||||

| 6. Assessment of Quality Of Life | AQOL | 1999 | 199939 | 15 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 7. Authentic Happiness Index | AHI | 2005 | 200540 | 20 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 8. Basic Psychological Needs Scale | BPNS | 2003 | 200341 | 21 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 9. BBC Subjective Well-Being Scale | BBC-SWB | 2011 | 201342 | 24 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 10. Beck Depression Index-2 | BDI-2 | 1961 | 199643 | 21 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 11. Biopsychosocialspiritual Inventory | BIOPSSI | 2007 | 200744 | 41 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 12. Cantril Self-Anchoring Striving Scale | CL | 1965 | 196545 | 1 | ● | ||||||

| 13. CASP-19 (Control, Autonomy, Self-realisation and Pleasure) | C19 | 2003 | 200346 | 19 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 14. Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale-Revised | CESD-R | 1977 | 201147 | 20 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 15. Chinese Happiness Inventory | CHI | 1997 | 199748 | 48 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 16. Depression-Happiness Scale-Short | DHS-S | 1993 | 200449 | 25 | ● | ||||||

| 17. Emotional Well-Being Scale | EWBS | 2011 | 201150 | 13 | ● | ||||||

| 18. EUROQOL-5D-5L | EQ-5D-5L | 1990 | 201151 | 5 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 19. EURO-D | EURO-D | 1999 | 199952 | 12 | ● | ||||||

| 20. EUROHIS-QOL | E-QOL | 1998 | 200353 | 8 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 21. Flourishing Scale | FS | 2010 | 201014 | 8 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 22. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General Population† | FACT-GP | 1993 | 200554 | 21 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 23. Functional Well-Being Scale | FWBS | 2015 | 201555 | 10 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 24. General Health Questionnaire | GHQ12 | 1978 | 198856 | 12 | ● | ||||||

| 25. Goteborg Quality of Life Instrument | GQLI | 1967 | 199057 | 15 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 26. Happiness Measures | HM | 1966 | 197358 | 2 | ● | ||||||

| 27. Health and Well-Being assessment | HWB | 2005 | 200559 | 20 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 28. Health Utilities Index-3 | HUI-3 | 1996 | 199860 | 8 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 29. Herth Hope Index | HHI | 1991 | 199261 | 12 | ● | ||||||

| 30. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | HADS | 1983 | 198362 | 14 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 31. ICECAP-A | ICECAP-A | 2012 | 201263 | 5 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 32. ICECAP-O | ICECAP-O | 2008 | 200864 | 5 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 33. ICOPPE (Interpersonal, Community, Occupational, Physical, Psychological, and Economic well-being) | ICOPPE | 2015 | 201526 | 21 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| 34. InCharge Financial Distress/Well-Being Scale | IFDFWS | 2006 | 200665 | 8 | ● | ● | |||||

| 35. Inventory of Positive Psychological Attitudes | IPPA | 1991 | 199166 | 32 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 36. Jarel Spiritual Well-Being Scale | JSWBS | 1996 | 199667 | 21 | ● | ● | |||||

| 37. Kellner's Symptom Questionnaire | KSQ | 1987 | 198768 | 92 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 38. Life Orientation Test-Revised | LOT-R | 1985 | 199469 | 10 | ● | ||||||

| 39. Life Satisfaction Index-A | LSI-A | 1961 | 196170 | 20 | ● | ● | |||||

| 40. Life Satisfaction Questionnaire-9 | LISAT9 | 1991 | 199171 | 9 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| 41. Meaning in Life Questionnaire | MLQ | 2006 | 200672 | 10 | ● | ● | |||||

| 42. Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing | MYCAW | 1996 | 200773 | 3 | ● | ||||||

| 43. Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness | MUNSH | 1980 | 198074 | 24 | ● | ||||||

| 44. Mental Health Continuum-Short Form | MHC-SF | 2002 | 200575 | 14 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 45. Mental Health Inventory-5 | MHI5 | 1983 | 198876 | 5 | ● | ||||||

| 46. Mental Physical Spiritual Well-Being Scale | MPS | 1995 | 199577 | 30 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 47. Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire-30 | MASQ-D30 | 1991 | 201078 | 30 | ● | ● | |||||

| 48. Multicultural Quality of Life Index | MQLI | 2011 | 201179 | 10 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| 49. Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire-Brief | MPQ | 1982 | 200280 | 155 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 50. Multiple Affect Adjective Check List-Revised | MAACL-R | 1965 | 198381 | 132 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 51. Nottingham Health Profile | NHP | 1975 | 198582 | 45 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 52. Older Adult Health and Mood Questionnaire | OAHMQ | 1995 | 199583 | 22 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 53. Ontological Well-Being Scale | OWBS | 2013 | 201384 | 24 | ● | ||||||

| 54. Orientations To Happiness | OTH | 2005 | 200585 | 18 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 55. Oxford Happiness Questionnaire | OHQ | 1989 | 200286 | 29 | ● | ||||||

| 56. Perceived Wellness Survey | PWS | 1997 | 199787 | 36 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 57. Personal Growth Initiative Scale | PGIS | 1998 | 199888 | 9 | ● | ||||||

| 58. Personal Wellbeing Index-Adult | PWI-A | 1994 | 201389 | 7 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| 59. Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Morale Scale | PGCMS | 1972 | 197590 | 17 | ● | ● | |||||

| 60. Physical, Mental and Social Well-Being Scale | PMSW-21 | 2014 | 201491 | 21 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 61. Positive and Negative Affect Scale | PANAS | 1988 | 198892 | 12 | ● | ||||||

| 62. Positive Functioning Inventory | PFI-12 | 2014 | 201415 | 12 | ● | ||||||

| 63. Positive Mental Health instrument | PMH | 2011 | 201193 | 47 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 64. Profile Of Mood States-Short | POMS2 | 1971 | 198394 | 37 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 65. Psychological General Well-Being Index | PGWB-S | 1970 | 200695 | 6 | ● | ||||||

| 66. Public Health Surveillance Well-Being Scale | PHS-WB | 2012 | 201216 | 10 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| 67. Purpose in Life Test-Short Form | PIL-SF | 1964 | 201196 | 20 | ● | ● | |||||

| 68. Quality of Life Index-Generic | QOLI-G | 1985 | 198597 | 66 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| 69. Quality of Life Inventory | QOLI | 1988 | 198898 | 17 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| 70. Quality of Well-Being Self-Administered | QWB-SA | 1970 | 199799 | 10 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 71. Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being | QEWB | 2010 | 2010100 | 21 | ● | ● | |||||

| 72. Questions on Life Satisfaction | QOLS | 1988 | 2000101 | 16 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 73. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale | RSES | 1965 | 1965102 | 10 | ● | ||||||

| 74. Ryff's Scales of Psychological Well-Being | PWB | 1989 | 1995103 | 54 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 75. Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale | SHIS | 2009 | 2009104 | 12 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 76. Satisfaction With Life Scale | SWLS | 1985 | 1985105 | 5 | ● | ||||||

| 77. Scale of Positive And Negative Experience | SPANE | 2010 | 201014 | 12 | ● | ||||||

| 78. Self-Evaluated Quality Of Life Questionnaire | SEQOL | 2003 | 2003106 | 317 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| 79. Serenity Scale-Brief | SS-B | 1993 | 2009107 | 22 | ● | ● | |||||

| 80. Short form 36 | SF-36v2 | 1988 | 1996 (JE Ware, M Kosinski, JE Dewey. How to score version 2 of the SF-36 health survey (standard & acute forms): Quality Metric Incorporated, 2000) | 36 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 81. Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale | SHAPS | 1995 | 1995108 | 14 | ● | ||||||

| 82. Social Production Function-IL | SPF-IL | 2005 | 2005109 | 58 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 83. Social Well-being Scale | SWS | 1998 | 1998110 | 50 | ● | ||||||

| 84. Spiritual Well-Being Scale | SP-WB-S | 1982 | 1982111 | 20 | ● | ||||||

| 85. Spirituality Index of Well-Being | SIWB | 2004 | 2004112 | 12 | ● | ● | |||||

| 86. State Anxiety Inventory | SAI | 1970 | 1992113 | 6 | ● | ||||||

| 87. State-Trait Cheerfulness Inventory | STCI | 1996 | 1996114 | 30 | ● | ||||||

| 88. Steinhauser Spiritual Concern Probe | SSCP | 2006 | 2006115 | 1 | ● | ● | |||||

| 89. Subjective Happiness Scale | SHS | 1999 | 1999116 | 4 | ● | ||||||

| 90. Subjective Vitality Scale | SVS | 1997 | 1997117 | 7 | ● | ● | |||||

| 91. Temporal Satisfaction With Life Scale | TSWLS | 1985 | 1998118 | 15 | ● | ||||||

| 92. The Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire | SP-WB-Q | 2003 | 2003119 | 20 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

| 93. The Spirituality Scale | SS | 2005 | 2005120 | 23 | ● | ● | ● | ||||

| 94. Valued Living Questionnaire | VLQ | 1999 | 2010121 | 20 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 95. Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale-Short | WEMWBS | 1983 | 2009122 | 7 | ● | ||||||

| 96. Well-Being Picture Scale | WPS | 1979 | 2005123 | 10 | ● | ||||||

| 97. WHO-5 | WHO5 | 1982 | 1998124 | 5 | ● | ||||||

| 98. WHO-Brief Spiritual, Religious and Personal Beliefs | WHO-QBF | 1995 | 2013125 | 34 | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● | ||

| 99. Zung Self Rating Depression Scale | ZSDS | 1965 | 1965126 | 20 | ● | ● | ● | ● | |||

*Items refer to questions.

†This tool was developed for cancer therapy, but this is a generic version.

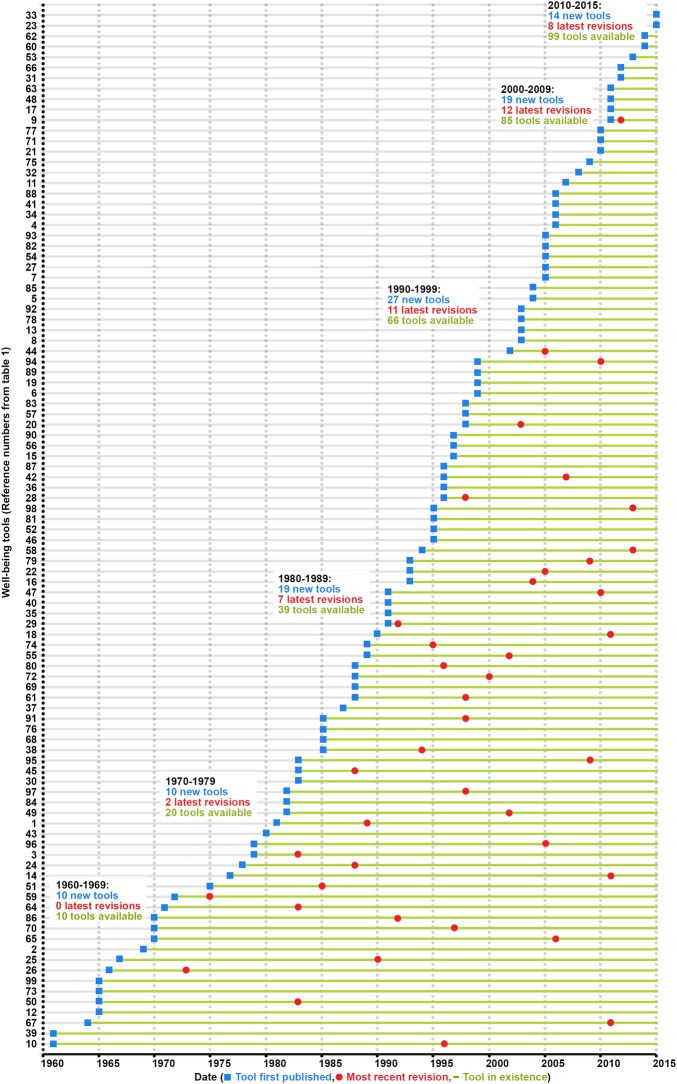

Figure 2.

Developmental timeline of well-being measures.

Instrument characteristics

Features of well-being instruments

The majority of measures contained multiple items (95/99), the largest containing 317 items (tool 78: SEQOL). Most of the instruments used verbal questions (97/99), however two tools were pictorial (tool 12: CL and tool 96: WPS). The fewest response options were found within simple yes/no questionnaires (tool 37: KSQ), while other tools offered up to 11 response options along a bipolar scale (tool 26: HM and tool 58: PWI-A). However, the majority of the tools used five-point bipolar Likert scales. Items asked individuals about the frequency; intensity; strength of agreement; or truth of specific and non-specific thoughts, feelings, experiences and statements. Instruments were named after key authors (11/99) such as the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, academic affiliation (7/99) as with the Oxford Happiness Questionnaire or organisational affiliation (5/99) as with the WHO-5. In the majority of cases, instruments were named after their key concept or approach.

Theoretical influence

The two theoretical influences most commonly reported in the literature were Diener's127 model of SWB and the WHO definition of health: “a complete state of physical, mental and social well-being”.128 Maslow's10 hierarchy of needs; Sen's11 capability approach; Antonovsky's129 theory of salutogenesis; Ryff's130 psychological well-being; Fisher et al's131 spiritual well-being model and self-determination theory132 were also referred to. In many cases, however, authors did not specify the theories that had influenced the design of their instrument.

Disciplinary influence

Most instruments were developed by interdisciplinary teams. However, classifying instruments by discipline proved impractical. Clinical psychology, medical sociology, public health, epidemiology, psychotherapy, health psychology, nursing, gerontology and primary care were among the disciplines represented. In some cases, such as the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (tool 96), multidisciplinary input spanned colleagues from medical schools, faculties of health and social care and schools of sociology and social policy.

Development of instruments over time

Although the systematic searches were limited to 1993 and 2014, almost half of the instruments we identified during this time had been first developed in the decades prior to this period (44/99). As shown in figure 2, the oldest instruments identified were developed in 1961 (tool 39: LSI-A and tool 10 V.1: BDI) while the newest tools were developed in 2015 (tool 33: ICOPPE and tool 23: FWBS). On average, eight tools had been designed every 5 years since 1960. The 1990s provided the biggest period for the development of new tools (n=27). Since 2010, 14 new tools and 8 revisions have already been published.

Three trends were observed over time. First, many newer measures contain fewer items, or are accompanied by short-form versions. Second, since the 1980s, with measures such as the Spiritual Well-being Scale (tool 84), spirituality has been incorporated into the assessment of well-being. Finally, over the past 15 years, there have been significant efforts to contrast the many measures of ill health and unhappiness with measures of positive functioning and adaptation to negative circumstances. Examples of these instruments included the Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (tool 75), Positive Functioning Inventory (tool 62) and the Flourishing Scale (Tool 21).

Definitions of well-being

Throughout the literature, incomplete and unclear definitions were provided. Broadly speaking, however, well-being was defined as a multidimensional construct.130 Greater specificity was provided by definitions that partitioned well-being into a subjective domain, and a separate objective domain.42

Subjective well-being

The subjective component of well-being was consistently divided into an ‘affective’ component concerned with emotions and a ‘cognitive’ component concerned with how people evaluate their own lives.50 109 The difference between SWB and terms used synonymously seemed to be unclear. SWB was noted as a synonym of happiness,116 mental well-being and mental health were acknowledged as being used interchangeably throughout the literature,133 and psychological well-being was used as an alternative phrasing for mental health.74 Authors were generally inconsistent on whether happiness should be understood as synonymous with SWB, specifically the affective portion of SWB, or a separate concept in itself. As the instruments were attempting to measure well-being through self-reported means, little explanation was given regarding how objective well-being should be conceptualised.

Health and well-being

The explicit difference between definitions of well-being and health appeared paradoxical. Authors frequently quoted the WHO definition of health as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, not merely the absence of a disease’.93 104 This understanding blurs the boundaries between health and well-being. As such, many measures of well-being resemble multidimensional measures of health.

Dimensions of well-being

Description of dimensions

Across the 99 instruments identified, 196 different dimensions were found. In the 10 tools identified (period 1960–1965), 18 of the 196 dimensions were identified. Of these, the most common dimension was ‘depression’ (found within 3/10 tools). In contrast, more favourable dimensions such as ‘positive affect’ (found within 8 tools) have gradually appeared within instruments over time, and reflect a conceptual rebalancing in the topic. Psychological well-being overall (n=13); physical well-being overall (n=12); social well-being overall (n=9); depression (n=9); positive affect (n=8) and relationships (n=8) appeared multiple times within the instruments examined.

The majority of instruments were multidimensional (67/99), and on average contained 5 dimensions (range 1–15). Instrument developers used: preset theory, literature searches, factor analytic methods, expert opinion or a combination of all four to determine which dimensions would be included in their tools. Unidimensional instruments were most frequent measures of ‘well-being overall’, ‘happiness’ or ‘depression’. Of these, the majority of dimensions appeared in only one of the tools identified in the review (69%, 136/196). A brief description of each dimension as defined by the authors can be found in online supplementary appendix 2; it should be noted that these definitions of dimensions may sometimes differ from dictionary definitions or current thinking.

bmjopen-2015-010641supp_appendix2.pdf (106.9KB, pdf)

Dimensions as determinants, states and consequences

Determinants are those factors thought to influence how people think and feel, states are those specific thoughts and feelings a person can have about their lives, and consequences are specific outcomes that happen as a result of a person's either positive or negative quality of life. However, some dimensions such as general health can be understood as being a possible precursor to well-being, being central to the idea of well-being and simultaneously being influenced by how happy or satisfied a person feels about their life. Although hundreds of dimensions of well-being were identified, there was little differentiation between which were considered determinants of well-being, which were states of being well and which were consequences of a person's general health or well-being.

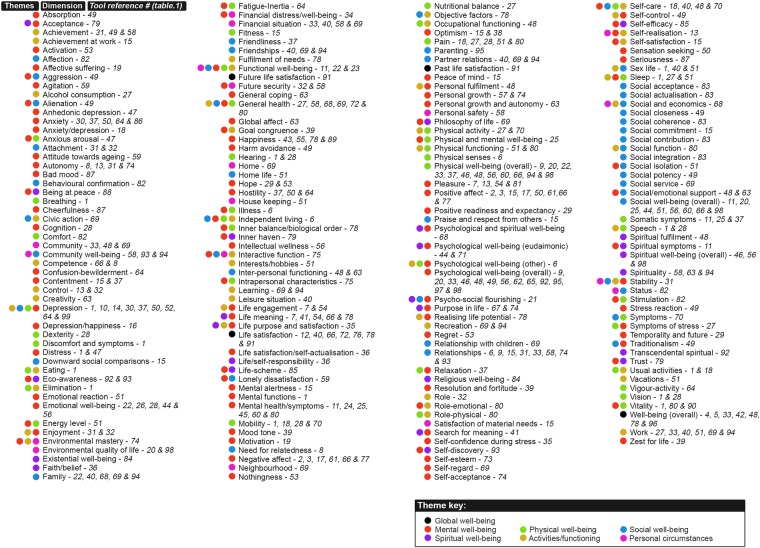

Dimensions linked to themes

The dimensions clustered around six key themes: ‘mental well-being’, ‘social well-being’, ‘physical well-being’, ‘spiritual well-being’, ‘personal circumstances’ and ‘activities and functioning’. A seventh set of dimensions were identified that attempted to measure ‘well-being overall’ in a global sense. Table 2 contains a brief description of each theme, and the number of dimensions linked to each. The majority of dimensions were linked to ‘mental well-being’, followed by ‘social well-being’ and ‘activities and functioning’.

Table 2.

Descriptions of the themes identified and the reoccurring dimensions within them

| Themes | Theme description |

|---|---|

| Mental well-being |

Dimensions linked to the theme of mental well-being assess the psychological, cognitive and emotional quality of a person's life. This includes the thoughts and feelings that individuals have about the state of their life, and a person's experience of happiness. |

| Social well-being |

Social well-being concerns how well an individual is connected to others in their local and wider social community. This includes social interactions, the depth of key relationships and the availability of social support. |

| Activities and functioning | The focus of this theme is the behaviour and activities that characterise daily life. This involves the specific activities we fill our time with, and our ability to undertake these tasks. |

| Physical well-being |

Physical well-being refers to the quality and performance of bodily functioning. This includes having the energy to live well, the capacity to sense the external environment and our experiences of pain and comfort. |

| Spiritual well-being |

Spiritual well-being is concerned with meaning, a connection to something greater than oneself and in some cases faith in a higher power. |

| Personal circumstances | These dimensions are related to the conditions and external pressures that an individual faces. This involves numerous environmental and socioeconomic concerns such as financial security. |

A thematic framework of well-being

An organised inventory of well-being dimensions is provided in figure 3. Each dimension is linked to the specific instruments that measure it, using the reference numbers found in table 1. Colour coding is used to highlight the themes of well-being that each dimension reflects. A glossary including definitions for each of the dimensions is provided in the online supplementary appendix 2.

Figure 3.

A thematic framework of well-being.

Discussion

We have provided a detailed inventory of 99 generic measures of adult well-being, a timeline illustrating the development of these tools over the past 50 years and a thematically catalogued register of 196 available dimensions. The evidence suggests that there is little consistent agreement on how well-being should be measured, how instruments should be designed or which dimensions should be included.

In previous reviews,30 31 60 or fewer instruments were identified; however, in our review 99 are reported. We believe the reasons for this are twofold. First, our initially agreed definition of well-being5 was deliberately broad, in order to reflect the multiple definitions in use. As a result, measures of happiness, for example, which touched on relevant content, were included, even though they have featured less frequently in previous reviews. Second, the current review used a wider variety of databases and hand searching. This decision was taken in order to ensure that measures used across disciplines were identified. In a topic as diverse as well-being, there is a need for both highly focused and widely scoped reviews. Narrowly focused reviews are able to provide more detailed insight on a smaller range of widely used tools, while reviews with a wider focus are able to focus on developments over time and the existence of lesser known tools, which may help researchers address their specific hypotheses.

We report consistent growth in the number of well-being instruments being developed, supporting the claim that there has been little unanimous agreement on how well-being should be measured. The growth observed is likely due to increasing multidisciplinary interest in the topic. For example, the first tools developed in the 1960s were heavily geared towards psychological and medical assessment; however, our work highlights a diverse set of tools, many the products of cross-disciplinary collaborations that draw on influences across different schools of thought. The spike in the number of instruments developed in the past 20 years in particular may have been influenced by the growing academic recognition that self-reported data produced by measures of well-being have demonstrable empirical and economic value.134

The current review identified substantial heterogeneity in how well-being was defined and used. Taken together, however, well-being should be understood as a multidimensional construct, reflecting themes that often overlap. It contains positive phenomena such as joy and social acceptance, negative phenomena such as anxiety and pain, subjective feelings and perceptions, and more ‘objective’ material circumstances or health states. Given its breadth, and the field's inability to establish an agreed definition, it may be more advantageous to use ‘well-being’ as an umbrella term reflecting the above concepts, instead of as a distinct unitary concept. Greater specificity should instead be reserved for dimensions of well-being.

The review also raises an important point about the difference between measures of well-being and measures of health. Many of the multidimensional measures of well-being strongly resemble measures of general health. Drawing a distinction between general well-being and general health may be too subtle; however, ‘SWB’ may differ from health in that it inherently targets how individuals think and feel about the quality of their own lives.127

The value and use of the measurement instruments will vary. Short measures of global well-being, such as the Arizona Integrative Outcomes Scale (AIOS) or the WHO-5 provide quick global snapshots on well-being, while taking up very little time from participants. In comparison, broader scoped instruments such as the Biopsychosocialspiritual Inventory (BIOPSSI) or the Mental Physical Spiritual Well-Being Scale (MPS) assess well-being separately across themes, and are thus able to provide a more comprehensive assessment. Other instruments assess more specific dimensions such as financial distress/well-being or social acceptance. These instruments are conceptually narrower and, as a result, are better equipped to facilitate more focused assessment.

We limited the inclusion criteria to measurement instruments that were used as generic tools for adults. Although this meant that we will have missed measures of well-being for use in condition-specific and context-specific instances, the decision was justified on pragmatic grounds in order to keep the review more focused on measures for use across populations. The extensive literature, inconsistent phrasing and disorganisation remain significant challenges for those conducting systematic reviews on the topic of well-being. It is unlikely that any search strategy could collate a definitive list of instruments; however, hopefully the broad approach taken in the current work is able to complement the selective reviews already in existence. In contrast to the psychometric focus of previous reviews, the objective of our work was to inform researchers about the dimensions available and the thematic differences among instruments. Further research should investigate the psychometric properties of this wider set of tools, with a specific focus on the issue of content and construct validity. Merging these strands of work should strengthen the methodological quality and our understanding of the subject.

A long list of well-being measures has been provided, but ambiguity surrounding the measurement of well-being remains. In the current work, we have attempted to be inclusive, rather than attempting to consolidate the measurement options; however, additional research should be conducted in order to investigate whether so many measures are necessary. For example, some of the measures available may be too similar to other instruments already in use. Others developed many years ago may simply no longer be of value due to the ongoing development of newer instruments or because they are based on outdated theories. Work to clarify which instruments are necessary should ideally tie in with psychometric work referred to above.

Further research should also focus on better understanding the conceptual similarities and differences between different dimensions of well-being. The quantitative difference between some concepts such as happiness and emotional well-being, or life purpose and life meaning, remain unclear. Unhelpfully, terms like functioning, welfare, wellness and satisfaction continue to be used interchangeably. Further research should seek to investigate whether the conceptual underpinnings of the measures identified are defensible. Progress will depend on researchers being more specific about definitions, selective about which measures are used and more cautious about how well-being terms are used.

Conclusion

Ambiguity surrounding how well-being is conceptualised and measured prompted us to review the measurement options available, their development over time and the dimensions within them. A comprehensive overview of available instruments has been provided; however, we do not offer a recommendation for the use of any one specific instrument. Instead, we reiterate that the most appropriate measure of well-being will depend on the dimensions of well-being of most interest, in coordination with psychometric guidance. We hope the framework provided will encourage researchers to be more explicit about what specific themes or dimensions they hope to measure. The consistent rate at which new instruments have been developed suggests that continued growth can be expected. While significant empirical and policy-related developments have been made in the past 10 years, continued progress will depend on equal amounts of effort focused on understanding the methods and measures used to collect well-being data.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the input of Leala Watson for her work on the systematic searches, and Louise Crathorne for her help preparing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Leala Watson; Louise Crathorne.

Contributors: The initial motivation for a review on the topic came from AM-L. The core sections of the review were formulated by M-JL, AM-L and PD. The search strategy was devised by AM-L and Leala Watson (LW). Screening records was undertaken by M-JL and AM-L, and any discrepancies were resolved through discussion with PD. Data from these records were extracted by M-JL and AM-L. M-JL and AM-L also undertook the qualitative thematic analysis, with PD examining the qualitative coding and naming of thematic domains for consistency. M-JL designed all figures, with comments and suggestions from AM-L and PD. Preparation of the manuscript was undertaken by M-JL, AM-L and PD, with considerable input from all authors.

Funding: This research was supported by a University of Exeter Medical School PhD Studentship.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Leala Watson and Louise Crathorne

References

- 1.Blanchflower DG, Oswald AJ. International happiness: a new view on the measure of performance. Acad Manag Perspect 2011;25:6–22. 10.5465/AMP.2011.59198445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stiglitz JE, Sen A, Fitoussi J-P. Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hicks S, Tinkler L, Allin P. Measuring subjective well-being and its potential role in policy: perspectives from the UK office for national statistics. Soc Indicators Res 2013;114:73–86. 10.1007/s11205-013-0384-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naci H, Ioannidis JP. Evaluation of wellness determinants and interventions by citizen scientists. JAMA 2015;314:121–2. 10.1001/jama.2015.6160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maggino F. Assessing the subjective wellbeing of nations. In: Glatzer W, Camfield L, Møller V, Rojas M, eds. Global handbook of quality of life. Springer, 2015:803–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krueger AB, Stone AA. Progress in measuring subjective well-being. Science 2014;346:42–3. 10.1126/science.1256392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stranges S, Samaraweera PC, Taggart F et al. Major health-related behaviours and mental well-being in the general population: the Health Survey for England. BMJ Open 2014;4:e005878 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deci EL, Ryan RM. Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: an introduction. J Happiness Stud 2008;9:1–11. 10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dodge R, Daly AP, Huyton J et al. The challenge of defining wellbeing. Int J Wellbeing 2012;2:222–35. 10.5502/ijw.v2i3.4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maslow AH. A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 1943;50:370–96. 10.1037/h0054346 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sen A. Commodities and capabilities. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brief AP, Butcher AH, George JM et al. Integrating bottom-up and top-down theories of subjective well-being: the case of health. J Pers Soc Psychol 1993;64:646 10.1037/0022-3514.64.4.646 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Layard R. Measuring subjective well-being. Science 2010;327:534–5. 10.1126/science.1186315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W et al. New well-being measures: short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indicators Res 2010;97:143–56. 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph S, Maltby J. Positive functioning inventory: initial validation of a 12-item self-report measure of well-being. Psychol Wellbeing 2014;4:15 10.1186/s13612-014-0015-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bann CM, Kobau R, Lewis MA et al. Development and psychometric evaluation of the public health surveillance well-being scale. Qual Life Res 2012;21:1031–43. 10.1007/s11136-011-0002-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gallagher MW, Lopez SJ, Preacher KJ. The hierarchical structure of well-being. J Pers 2009;77:1025–50. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00573.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gasper D. Understanding the diversity of conceptions of well-being and quality of life. J Socio Econ 2010;39:351–60. 10.1016/j.socec.2009.11.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keyes CL, Waterman MB. Dimensions of well-being and mental health in adulthood. In: Bornstein M, Davidson L, Keyes CLM, Moore K, Rogers M, eds Well-being: positive development throughout the life course. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2003:477–97. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wish NB. Are we really measuring the quality of life? Well-being has subjective dimensions, as well as objective ones. Am J Econ Sociol 1986;45:93–9. 10.1111/j.1536-7150.1986.tb01906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Şimşek ÖF. Happiness revisited: ontological well-being as a theory-based construct of subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud 2009;10:505–22. 10.1007/s10902-008-9105-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bensley RJ. Defining spiritual health: a review of the literature. J Health Educ 1991;22:287–90. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977;196:129–36. 10.1126/science.847460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larson JS. The conceptualization of health. Med Care Res Rev 1999;56:123–36. 10.1177/107755879905600201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.OECD. How's life? 2013. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prilleltensky I, Dietz S, Prilleltensky O et al. Assessing multidimensional well-being: development and validation of the I coppe scale. J Community Psychol 2015;43:199–226. 10.1002/jcop.21674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steptoe A, Deaton A, Stone AA. Subjective wellbeing, health, and ageing. Lancet 2015;385:640–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61489-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stewart L, Skinner L, Weiss M et al. Start well, live better—a manifesto for the public's health. J Public Health (Oxf) 2015;37:3–5. 10.1093/pubmed/fdu113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schiaffino KM. Other measures of psychological well-being: the Affect Balance Scale (ABS), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), Life Satisfaction Index-A (LSI-A), Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), and State-Trait Anxiety Index (STAI). Arthritis Care Res 2003;49:S165–S74. 10.1002/art.11408 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McDowell I. Measures of self-perceived well-being. J Psychosom Res 2010;69:69–79. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindert J, Bain PA, Kubzansky LD et al. Well-being measurement and the WHO health policy Health 2010: systematic review of measurement scales. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:731–40. 10.1093/eurpub/cku193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009;151:264–9. 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sintonen H, Pekurinen M. A generic 15 dimensional measure of health-related quality of life (15D). J Soc Med 1989;26:85–96. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bradburn NM. The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Ciompany, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kammann R, Flett R. Affectometer 2: a scale to measure current level of general happiness. Aust J Psychol 1983;35:259–65. 10.1080/00049538308255070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bernheim JL, Theuns P, Mazaheri M et al. The potential of anamnestic comparative self-assessment (ACSA) to reduce bias in the measurement of subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud 2006;7:227–50. 10.1007/s10902-005-4755-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bell IR, Cunningham V, Caspi O et al. Development and validation of a new global well-being outcomes rating scale for integrative medicine research. BMC Complement Altern Med 2004;4:1–10. 10.1186/1472-6882-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hawthorne G, Richardson J, Osborne R. The Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) instrument: a psychometric measure of health-related quality of life. Qual Life Res 1999;8:209–24. 10.1023/A:1008815005736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seligman ME, Steen TA, Park N et al. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Am Psychol 2005;60:410–21. 10.1037/0003-066X.60.5.410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gagné M. The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motiv Emotion 2003;27:199–223. 10.1023/A:1025007614869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pontin E, Schwannauer M, Tai S et al. A UK validation of a general measure of subjective well-being: the modified BBC subjective well-being scale (BBC-SWB). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2013;11:150 10.1186/1477-7525-11-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd edn San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Katerndahl D, Oyiriaru D. Assessing the biopsychosociospiritual model in primary care: development of the biopsychosociospiritual inventory (BioPSSI). Int J Psychiatry Med 2007;37:393–414. 10.2190/PM.37.4.d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cantril H. Pattern of human concern. New Brunswick: Rutgers University, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hyde M, Wiggins RD, Higgs P et al. A measure of quality of life in early old age: the theory, development and properties of a needs satisfaction model (CASP-19). Aging Ment Health 2003;7:186–94. 10.1080/1360786031000101157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van Dam NT, Earleywine M. Validation of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale—Revised (CESD-R): pragmatic depression assessment in the general population. Psychiatry Res 2011;186:128–32. 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu L, Shih J. Personality and happiness: is mental health a mediator? Pers Individual Differ 1997;22:249–56. 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00187-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joseph S, Linley PA, Harwood J et al. Rapid assessment of well-being: the Short Depression-Happiness Scale (SDHS). Psychol Psychother 2004;77:463–78. 10.1348/1476083042555406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Şimşek ÖF. An intentional model of emotional well-being: the development and initial validation of a measure of subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud 2011;12:421–42. 10.1007/s10902-010-9203-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011;20:1727–36. 10.1007/s11136-011-9903-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prince MJ, Reischies F, Beekman AT et al. Development of the EURO-D scale—a European, Union initiative to compare symptoms of depression in 14 European centres. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:330–8. 10.1192/bjp.174.4.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schmidt S, Mühlan H, Power M. The EUROHIS-QOL 8-item index: psychometric results of a cross-cultural field study. Eur J Public Health 2006;16:420–8. 10.1093/eurpub/cki155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brucker PS, Yost K, Cashy J et al. General population and cancer patient norms for the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G). Eval Health Prof 2005;28:192–211. 10.1177/0163278705275341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Evers KE, Castle PH, Fernandez AC et al. The Functional Well-Being Scale: a measure of functioning loss due to well-being-related barriers. J Health Psychol 2015;20:113–20. 10.1177/1359105313500094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldberg D, Williams P. Users’ guide to the general health questionnaire. Windsor: nferNelson, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tibblin G, Tibblin B, Peciva S et al. “The Goteborg quality of life instrument”—an assessment of well-being and symptoms among men born 1913 and 1923. Methods and validity. Scand J Prim Health Care Suppl 1990;1:33–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fordyce MW. A review of research on the happiness measures: a sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Social Indicators Res 1988;20:355–81. 10.1007/BF00302333 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mills PR. The development of a new corporate specific health risk measurement instrument, and its use in investigating the relationship between health and well-being and employee productivity. Environ Health 2005;4:1 10.1186/1476-069X-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Furlong W, Feeny D, Torrance G et al. Multiplicative multi-attribute utility function for the Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3) system: a technical report: McMaster University Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis (CHEPA) Working Paper 1998: No. 98-11, 1998. http://fhs.mcmaster.ca/hug/wp9811.htm

- 61.Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs 1992;17:1251–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Al-Janabi H, Flynn TN, Coast J. Development of a self-report measure of capability wellbeing for adults: the ICECAP-A. Qual Life Res 2012;21:167–76. 10.1007/s11136-011-9927-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coast J, Flynn TN, Natarajan L et al. Valuing the ICECAP capability index for older people. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:874–82. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Prawitz AD, Garman ET, Sorhaindo B et al. InCharge financial distress/financial well-being scale: development, administration, and score interpretation. J Financ Counsel Plan 2006;17:34–50. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kass JD, Friedman R, Leserman J et al. An inventory of positive psychological attitudes with potential relevance to health outcomes: validation and preliminary testing. Behav Med 1991;17:121–9. 10.1080/08964289.1991.9937555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hungelmann J, Kenkel-Rossi E, Klassen L et al. Focus on spiritual well-being: harmonious interconnectedness of mind-body-spirit—use of the JAREL Spiritual Well-Being Scale. Geriatr Nurs 1996;17:262–6. 10.1016/S0197-4572(96)80238-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kellner R. A symptom questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry 1987;48: 268–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol 1994;67:1063–78. 10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neugarten BL, Havighurst RJ, Tobin SS. The measurement of life satisfaction. J Gerontol 1961;16:134–43. 10.1093/geronj/16.2.134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Fugl-Meyer AR, Bränholm I-B, Fugl-Meyer KS. Happiness and domain-specific life satisfaction in adult northern Swedes. Clin Rehabil 1991;5:25–33. 10.1177/026921559100500105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Steger MF, Frazier P, Oishi S et al. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J Couns Psychol 2006;53:80–93. 10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paterson C, Thomas K, Manasse A et al. Measure Yourself Concerns and Wellbeing (MYCaW): an individualised questionnaire for evaluating outcome in cancer support care that includes complementary therapies. Complement Ther Med 2007;15:38–45. 10.1016/j.ctim.2006.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kozma A, Stones MJ. The measurement of happiness: development of the Memorial University of Newfoundland Scale of Happiness (MUNSH). J Gerontol 1980;35:906–12. 10.1093/geronj/35.6.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keyes CL. The subjective well-being of America's youth: toward a comprehensive assessment. Adolesc Fam Health 2006;4:3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Stewart AL, Hays RD, Ware JE Jr. The MOS short-form general health survey: reliability and validity in a patient population. Med Care 1988;26:724–35. 10.1097/00005650-198807000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Vella-Brodrick DA, Allen FC. Development and psychometric validation of the mental, physical, and spiritual well-being scale. Psychol Rep 1995;77:659–74. 10.2466/pr0.1995.77.2.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wardenaar KJ, van Veen T, Giltay EJ et al. Development and validation of a 30-item short adaptation of the Mood and Anxiety Symptoms Questionnaire (MASQ). Psychiatry Res 2010;179:101–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mezzich JE, Cohen NL, Ruiperez MA et al. The Multicultural Quality of Life Index: presentation and validation. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:357–64. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01609.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Psychol Assess 2002;14:150–63. 10.1037/1040-3590.14.2.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zuckerman M, Lubin B, Rinck CM. Construction of new scales for the multiple affect adjective check list. J Behav Assess 1983;5:119–29. 10.1007/BF01321444 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hunt S, McEwen J, McKenna S. Measuring health status: a new tool for clinicians and epidemiologists. Br J Gen Pract 1985;35:185–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kemp BJ, Adams BM. The Older Adult Health and Mood Questionnaire: a measure of geriatric depressive disorder. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 1995;8:162–7. 10.1177/089198879500800304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Şimşek ÖF, Kocayörük E. Affective reactions to one's whole life: preliminary development and validation of the ontological well-being scale. J Happiness Stud 2013;14:309–43. 10.1007/s10902-012-9333-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Peterson C, Park N, Seligman ME. Orientations to happiness and life satisfaction: the full life versus the empty life. J Happiness Stud 2005;6:25–41. 10.1007/s10902-004-1278-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hills P, Argyle M. The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: a compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Pers Individual Differ 2002;33:1073–82. 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00213-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Adams T, Bezner J, Steinhardt M. The conceptualization and measurement of perceived wellness: integrating balance across and within dimensions. Am J Health Promot 1997;11:208–18. 10.4278/0890-1171-11.3.208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Robitschek C. Personal growth initiative: the construct and its measure. Meas Eval Couns Dev 1998;30:183–98. [Google Scholar]

- 89.International Wellbeing Group. Personal wellbeing index. 5th edn Melbourne: Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lawton MP. The Philadelphia geriatric center morale scale: a revision. J Gerontol 1975;30:85–9. 10.1093/geronj/30.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Supranowicz P, Paź M. Holistic measurement of well-being: psychometric properties of the physical, mental and social well-being scale (PMSW-21) for adults. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig 2014;65:251–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vaingankar JA, Subramaniam M, Chong SA et al. The positive mental health instrument: development and validation of a culturally relevant scale in a multi-ethnic Asian population. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2011;9:92–92. 10.1186/1477-7525-9-92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shacham S. A shortened version of the profile of mood states. J Pers Assess 1983;47:305–6. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4703_14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Grossi E, Groth N, Mosconi P et al. Development and validation of the short version of the Psychological General Well-Being Index (PGWB-S). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006;4:88 10.1186/1477-7525-4-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Schulenberg SE, Schnetzer LW, Buchanan EM. The purpose in life test-short form: development and psychometric support. J Happiness Stud 2011;12:861–76. 10.1007/s10902-010-9231-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ferrans CE, Powers MJ. Quality of life index: development and psychometric properties. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1985;8:15–24. 10.1097/00012272-198510000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Frisch MB, Cornell J, Villanueva M et al. Clinical validation of the Quality of Life Inventory. A measure of life satisfaction for use in treatment planning and outcome assessment. Psychol Assess 1992;4:92–101. 10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.92 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kaplan RM, Sieber WJ, Ganiats TG. The quality of well-being scale: comparison of the interviewer-administered version with a self-administered questionnaire. Psychol Health 1997;12:783–91. 10.1080/08870449708406739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Waterman AS, Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL et al. The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic Well-Being: psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. J Posi Psychol 2010;5:41–61. 10.1080/17439760903435208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Henrich G, Herschbach P. Questions on Life Satisfaction (FLZ M): a short questionnaire for assessing subjective quality of life. Eur J Psychol Assess 2000;16:150–9. 10.1027//1015-5759.16.3.150 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ryff CD, Keyes CLM. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J Pers Soc Psychol 1995;69:719–27. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bringsén Å, Andersson HI, Ejlertsson G. Development and quality analysis of the Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (SHIS). Scand J Public Health 2009;37:13–19. 10.1177/1403494808098919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ et al. The satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1985;49:71–5. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ventegodt S, Merrick J, Andersen NJ. Measurement of quality of life III. From the IQOL theory to the global, generic SEQOL questionnaire. Sci World J 2003;3:972–91. 10.1100/tsw.2003.77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kreitzer MJ, Gross CR, Waleekhachonloet OA et al. The Brief Serenity Scale a psychometric analysis of a measure of spirituality and well-being. J Holist Nurs 2009;27:7–16. 10.1177/0898010108327212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Snaith RP, Hamilton M, Morley S et al. A scale for the assessment of hedonic tone the Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1995;167:99–103. 10.1192/bjp.167.1.99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Nieboer A, Lindenberg S, Boomsma A et al. Dimensions of well-being and their measurement: the SPF-IL scale. Soc Indicators Res 2005;73:313–53. 10.1007/s11205-004-0988-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Keyes CLM. Social well-being. Soc Psychol Q 1998;61:121–40. 10.2307/2787065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Paloutzian RF, Ellison CW. Loneliness, spiritual well-being, and quality of life. In: Perlman LAPD, ed. Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. New York: Wiley, 1982:224–37. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Daaleman TP, Frey BB. The Spirituality Index of Well-Being: a new instrument for health-related quality-of-life research. Ann Fam Med 2004;2:499–503. 10.1370/afm.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Marteau TM, Bekker H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol 1992;31:301–6. 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ruch W, Köhler G, van Thriel C. To be in good or bad humour: construction of the state form of the State-Trait-Cheerfulness-inventory—STCI. Pers Individual Differ 1997;22:477–91. 10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00231-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Steinhauser KE, Voils CI, Clipp EC et al. “Are you at peace?”: one item to probe spiritual concerns at the end of life. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:101–5. 10.1001/archinte.166.1.101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lyubomirsky S, Lepper HS. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc Indicators Res 1999;46:137–55. 10.1023/A:1006824100041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ryan RM, Frederick C. On energy, personality, and health: subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. J Pers 1997;65:529–65. 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pavot W, Diener E, Suh E. The temporal satisfaction with life scale. J Pers Assess 1998;70:340–54. 10.1207/s15327752jpa7002_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Gomez R, Fisher JW. Domains of spiritual well-being and development and validation of the Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire. Pers Individual Differ 2003;35:1975–91. 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00045-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Delaney C. The spirituality scale development and psychometric testing of a holistic instrument to assess the human spiritual dimension. J Holist Nurs 2005;23:145–67. 10.1177/0898010105276180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Wilson KG, Sandoz EK, Kitchens J et al. The Valued Living Questionnaire: defining and measuring valued action within a behavioral framework. Psychol Rec 2011;60:249–72. [Google Scholar]

- 122.Stewart-Brown S, Tennant A, Tennant R et al. Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009;7:15 10.1186/1477-7525-7-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Gueldner SH, Michel Y, Bramlett MH et al. The well-being picture scale: a revision of the index of field energy. Nurs Sci Q 2005;18:42–50. 10.1177/0894318404272107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.World Health Organization. WHO (five) Well-Being Index: World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 125.Skevington SM, Gunson KS, O'Connell KA. Introducing the WHOQOL-SRPB BREF: developing a short-form instrument for assessing spiritual, religious and personal beliefs within quality of life. Qual Life Res 2013;22:1073–83. 10.1007/s11136-012-0237-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1965;12:63–70. 10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychol Bull 1984;95:542–75. 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization, as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19–22 June 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland 1948. Constitution of the World Health Organization. 2006. www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf

- 129.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 1989;57:1069 10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Fisher J, Francis L, Johnson P. Assessing spiritual health via four domains of spiritual wellbeing: the SH4DI. Pastoral Psychol 2000;49:133–45. 10.1023/A:1004609227002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 2000;55:68–78. 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Tennant R, Hiller L, Fishwick R et al. The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): development and UK validation. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007;5:63 10.1186/1477-7525-5-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kahneman D, Krueger AB. Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. J Econ Perspect 2006;20:3–24. 10.1257/089533006776526030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010641supp_appendix1.pdf (206.1KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2015-010641supp_appendix2.pdf (106.9KB, pdf)