Abstract

Objectives

To determine population attributable risks (PARs) estimates for factors associated with non-use of postnatal care (PNC) in Nigeria.

Design, setting and participants

The most recent Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS, 2013) was examined. The study consisted of 20 467 mothers aged 15–49 years. Non-use of PNC services was examined against a set of demographic, health knowledge and social structure factors, using multilevel regression analysis. PARs estimates were obtained for each factor associated with non-use of PNC in the final multivariate logistic regression model.

Main outcome

PNC services.

Results

Non-use of PNC services was attributed to 68% (95% CI 56% to 76%) of mothers who delivered at home, 61% (95% CI 55% to 75%) of those who delivered with the help of non-health professionals and 37% (95% CI 31% to 45%) of those who lacked knowledge of delivery complications in the study population. Multiple variable analyses revealed that non-use of PNC services among mothers was significantly associated with rural residence, household poverty, no or low levels of mothers' formal education, small perceived size of neonate, poor knowledge of delivery-related complications, and limited or no access to the mass media.

Conclusions

PAR estimates for factors associated with non-use of PNC in Nigeria highlight the need for community-based interventions regarding maternal education and services that focus on mothers who delivered their babies at home. Our study also recommends financial support from the Nigerian government for mothers from low socioeconomic settings, so as to minimise the inequitable access to pregnancy and delivery healthcare services with trained healthcare personnel.

Keywords: Postnatal care, Mortality, Nigeria

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our analysis was restricted to mothers who received postnatal care (PNC) services within 5 years prior to the survey; in order to minimise recall bias.

Data were from a population-based national respective survey with a response rate of about 98%.

This study was a cross-sectional design and therefore inferences on causes and effects could not be substantiated.

This study did not assess the quality of PNC offered to mothers.

Introduction

There is evidence that most maternal deaths occur during labour, delivery or the first 24 hours postpartum.1 2 Although the neonatal period is only 28 days, it accounts for as much as 38% of all deaths in children younger than 5 years.3 There could be a drastic reduction in these maternal and neonatal problems if women received the requisite medical attention and postnatal care (PNC) during the postnatal period (ie, healthcare services received in the first 6 weeks after delivery).4 The postnatal period is thus critical for the health and survival of both mother and newborn alike. It is against this background that the WHO has strongly advocated improvements of maternal health services as part of its Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI).5 The WHO recommends that women should be given PNC within the first 24 hours, followed by check-ups on the second or third day, and then on the seventh day after giving birth.4

Globally, PNC has been recognised to be crucial to the maintenance and promotion of the health and survival of a mother and her newborn baby. It also provides health professionals the opportunity of identifying, monitoring and managing the health conditions of both the mother and her baby during the postnatal period. Furthermore, health professionals use PNC to undertake health promotional programmes to encourage exclusive breast feeding, personal hygiene, appropriate infant feeding practices as well as family planning counselling and services.4

The government of Nigeria has made tremendous efforts to meet the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) relating to the survival of children under 5 years of age and that of mothers. However, the most recently estimated maternal mortality ratio indicated a slight rise of ∼6%—from 545 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births in 2008 to 576 per 100 000 live births in 2013,6 indicating poor maternal healthcare services. Neonatal mortality rates during this period decreased by 8%—from 40 deaths per 1000 live births to 37 deaths per 1000 live births.6 Despite the benefits and effectiveness of PNC, the 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) reported that 58% of Nigerian women had no postnatal check-ups despite the recommendations.6

Several population-based studies have been carried out on both use and non-use of PNC services, particularly in low and middle income countries, including Bangladesh,7 8 Indonesia9 and Timor-Leste.10 However, in Nigeria, the literature is limited. A majority of past studies were community-based studies that focused on small-scale research.11–13 Recently, a population-based study on determinants of PNC non-utilisation among women in Nigeria was conducted.14 However, this study did not examine the attributable risks of factors associated with non-use of PNC. Hence, this study aimed to extrapolate population attributable risk (PAR) proportions to provide estimates of the total magnitude of each of the factors associated with non-use of PNC in Nigeria. Results of our investigation using nationally representative data could provide policymakers with information to implement interventions that will encourage the patronage of PNC services among women, thereby improving maternal and newborn survival rates.

Methods

Data from the 2013 NDHS data set were used for this study. The 2013 NDHS household survey was conducted by the National Population Commission (NPC) in conjunction with ICF International. The household survey information on demographic and health issues such as maternal and child health, childhood mortality and education were gathered by interviewing eligible women and men of reproductive age, aged 15–49 and 15–59 years, respectively. Three questionnaires (household, women's and men's questionnaires) were used to record all information gathered. Sampling procedures used in the NDHS have earlier been published in detail elsewhere.15

A total of 38 948 women were successfully interviewed, yielding a response rate of 97.6%. More than 50% (20 467) of these women had the most recent birth within 5 years prior to the survey interview, and were used for our study analyses. The analysis was restricted to births that occurred within the previous 5 years because only those births had detailed information on the use of perinatal health services, and to limit the potential for differential recall of events from mothers who had delivered at very different durations prior to the survey date.

Study variables

Dependent variable

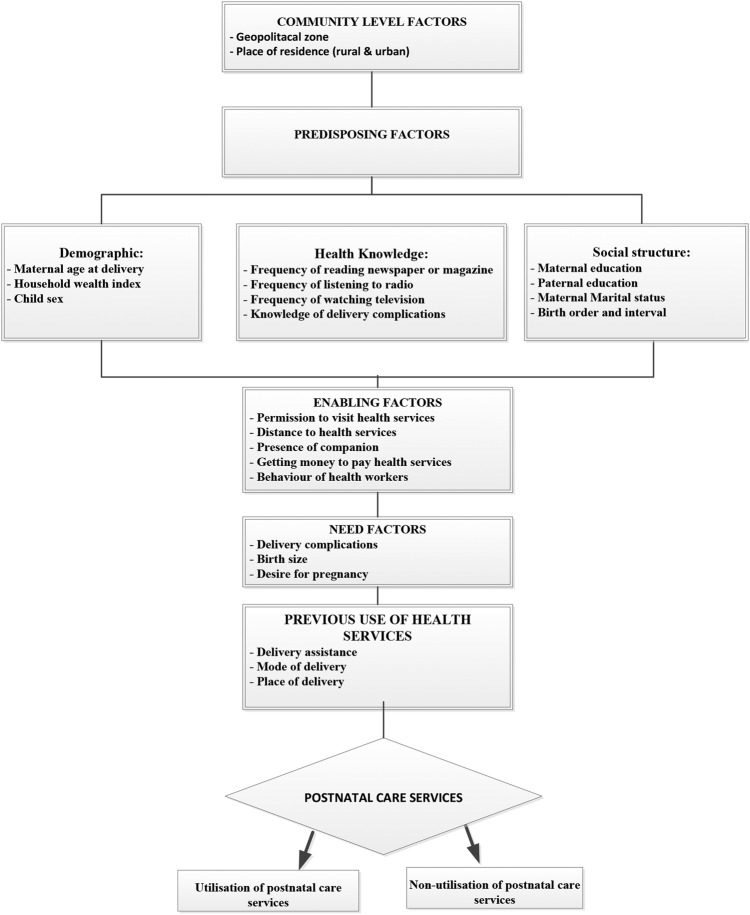

The outcome variable for this study was non-use of PNC services. This takes a binary form, such that PNC will be regarded as a ‘case’ (1= if healthcare service was not received during the first 6 weeks after delivery) or a ‘non-case’ (0= if healthcare service was received during the first 6 weeks of infant life). The outcome variable was examined against all potential confounding variables (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework adapted from Andersen's Behavioural Model.

Independent variables

A behavioural conceptual framework of maternal healthcare services developed by Andersen16 is frequently referenced in other studies on perinatal care services.9 17 18 As a result, our study used the Andersen16 framework as the basis for identifying key risk factors associated with non-use of PNC services in Nigeria. Figure 1 presents all potential confounding variables based on information available in the 2013 NDHS. These variables were classified into five distinct groups: community level factors (geopolitical zone and place of residence); predisposing level factors (demographic, health knowledge and social structure factors); demographic and social structure factors (household wealth index, level of mother's education, mother's age at delivery, level of father's education, mother's marital status, child's sex and a combination of birth order and birth interval); health knowledge characteristics (frequency of reading newspaper or magazine, frequency of watching television, frequency of listening to radio and knowledge of delivery complication); enabling factors (permission to visit health services, distance to health services, presence of companion, ability to pay for health services and behaviour of health workers); need factors (delivery complications, birth size and desire for pregnancy); and previous use of health services (delivery assistance, mode of delivery and place of delivery).

Statistical analysis

The prevalence of non-use of PNC services was described by conducting a frequency tabulation of all potential risk factors included in the study. Logistic regression generalized linear latent and mixed models (GLLAM) with the logit link and binomial family19 were then used for multivariable analyses that independently examined the effect of each factor, after adjusting for confounding variables.

A hierarchical modelling technique20 was used in the multivariable logistic regression to allow more distal factors to be appropriately examined without interference from more proximate factors. A five-stage model was used by following a similar conceptual framework to that described by Andersen16 (figure 1). First, community level factors were entered into the baseline model to assess their relationship with the study outcome. A manually processed stepwise backwards elimination was performed and variables with p values <0.05 were retained in the model. Second, predisposing level factors were examined with the community level factors that were significantly associated with non-use of PNC, and those variables with p values <0.05 were retained.

In the third stage, enabling level factors were investigated with the community and predisposing level factors that were significantly related with the study outcome. As before, those variables with p values <0.05 were retained. A similar procedure was used for need and previous use of health services level factors in the fourth and fifth stages, respectively. In our final model, we double–check for collinearity in order to reduce any statistical bias. All analyses were conducted using ‘SVY’ commands in STATA V.13.1 (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) to adjust for the cluster sampling survey design and weights.

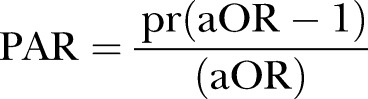

The PAR was calculated for the significant risk factors to estimate the contribution of each risk factor to the total risk for non-use of PNC services between 2009 and 2013. We obtained PAR and 95% CIs by using the following similar method employed by Stafford et al.21

|

where pr is the proportion of the population exposed to risk factors, and a OR was the adjusted OR for non-use of PNC.

Results

Of the weighted total of 20 467 mothers eligible for PNC services for their most recent live-born infants within 5 years preceding the 2013 NDHS survey interview date, ∼58% of the eligible mothers did not use PNC services during the first 6 weeks of an infant's life. The prevalence of mothers who were assisted by non-health professionals during delivery was ∼85% (95% CI 83.2% to 86.2%). Greater than three-quarters (81.9%; 95% CI 80.3% to 83.3%) of mothers delivered their infants at non-health facilities and 81% (95% CI 79.2% to 82.7%) of mothers were from poor households.

The multivariable analysis showed that community, predisposing, enabling, need and previous use of health services level factors were significantly associated with non-use of PNC services in Nigeria (table 1). Infants whose mothers resided in rural areas (OR=1.69; CI 1.40 to 2.06) had higher odds of not patronising PNC services compared with those living in urban areas. The odds of non-use of PNC services increased significantly among infants born to mothers from poor households (OR=1.66; CI 1.35 to 2.05) and those whose mothers had no formal education. A higher likelihood of non-use of PNC services was associated with infants whose mothers had no knowledge of delivery-related complications and lack of exposure to mass media, particularly watching television. It was also observed that attitude of health workers had a significant effect on non-use of PNC services among nursing mothers.

Table 1.

Distribution of characteristics, unadjusted and adjusted OR for factors associated with non-use of postnatal care services in Nigeria, 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS)

| N | %* (95% CI) | Unadjusted | Adjusted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | ||

| Environmental factor | ||||

| Residence type | ||||

| Urban | 7278 | 36.8 (33.4 to 40.3) | Ref | Ref |

| Rural | 13 189 | 69.4 (67.1 to 71.5) | 3.89 (3.20 to 4.73) | 1.69 (1.40 to 2.06) |

| Geopolitical zone | ||||

| North Central | 2890 | 50.2 (45.4 to 55.1) | Ref | |

| North East | 3434 | 67.7 (63.7 to 71.5) | 2.08 (1.59 to 2.71) | |

| North West | 7445 | 80.6 (77.1 to 83.6) | 4.11 (3.09 to 5.47) | |

| South East | 1719 | 38.7 (34.9 to 42.7) | 0.63 (0.48 to 0.81) | |

| South West | 2002 | 35.3 (31.4 to 39.4) | 0.54 (0.42 to 0.70) | |

| South South | 2977 | 22.6 (18.6 to 27.2) | 0.29 (0.21 to 0.40) | |

| Sociodemographic factor | ||||

| Household wealth index | ||||

| Rich | 3604 | 20.4 (17.8 to 23.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Middle | 7576 | 47.1 (44.6 to 49.6) | 3.48 (2.90 to 4.17) | 1.15 (0.98 to 1.34) |

| Poor | 9287 | 81.0 (79.2 to 82.7) | 16.7 (13.6 to 20.5) | 1.66 (1.35 to 2.05) |

| Mother's education | ||||

| Secondary or higher | 6758 | 29.0 (27.0 to 31.1) | Ref | Ref |

| Primary | 3915 | 51.2 (48.7 to 53.7) | 2.57 (2.29 to 2.89) | 0.98 (0.85 to 1.12) |

| No education | 9794 | 80.3 (78.4 to 82.0) | 9.97 (8.55 to 11.6) | 1.37 (1.17 to 1.61) |

| Mother's working status | ||||

| Working | 13 190 | 53.1 (50.9 to 55.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Not working | 7258 | 66.4 (63.6 to 69.0) | 1.75 (1.54 to 1.97) | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.92) |

| Mother's age (years) | ||||

| <20 | 2813 | 66.5 (63.7 to 69.2) | Ref | |

| 20–29 | 10 079 | 56.8 (54.5 to 59.0) | 0.66 (0.59 to 0.74) | |

| 30–39 | 6329 | 54.6 (52.3 to 56.8) | 0.61 (0.53 to 0.69) | |

| 40–49 | 1246 | 62.2 (58.7 to 65.6) | 0.83 (0.70 to 0.99) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Currently married | 19 397 | 58.5 (56.5 to 60.4) | Ref | |

| Formerly/never married | 1070 | 45.3 (41.1 to 49.6) | 0.59 (0.49 to 0.70) | |

| Father's education | ||||

| Secondary or higher | 8372 | 36.5 (34.3 to 38.8) | Ref | |

| Primary | 3661 | 56.4 (53.6 to 59.1) | 2.25 (1.99 to 2.54) | |

| No education | 7785 | 82.2 (80.3 to 84.0) | 8.04 (6.87 to 9.42) | |

| Birth rank and birth interval (years) | ||||

| 2nd or 3rd child, interval >2 | 7053 | 53.8 (51.3 to 56.2) | Ref | |

| First child | 3670 | 48.0 (45.3 to 50.7) | 0.79 (0.72 to 0.87) | |

| 2nd or 3nd child, interval ≤2 | 2094 | 54.9 (51.5 to 58.2) | 1.05 (0.93 to 1.18) | |

| 4th or more child, interval >2 | 6020 | 66.2 (64.2 to 68.2) | 1.69 (1.54 to 1.85) | |

| 4th or more child, interval ≤2 | 1630 | 69.5 (66.5 to 72.3) | 1.95 (1.70 to 2.25) | |

| Child sex | ||||

| Male | 10 282 | 57.3 (55.2 to 59.4) | Ref | |

| Female | 10 185 | 58.2 (56.1 to 60.3) | 1.04 (0.97 to 1.11) | |

| Health knowledge | ||||

| Frequency of reading newspaper or magazine | ||||

| At least once a week | 1228 | 22.0 (19.0 to 25.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Less than once a week | 1716 | 24.2 (21.2 to 27.5) | 1.14 (0.92 to 1.41) | 1.08 (0.81 to 1.45) |

| Never | 17 393 | 63.5 (61.6 to 65.4) | 6.19 (5.11 to 7.51) | 1.40 (1.09 to 1.79) |

| Frequency of listening to radio | ||||

| At least once a week | 7317 | 43.7 (41.3 to 46.1) | Ref | |

| Less than once a week | 5131 | 54.9 (51.8 to 58.0) | 1.57 (1.37 to 1.79) | |

| Never | 7951 | 72.6 (70.6 to 74.5) | 3.41 (3.02 to 3.85) | |

| Frequency of watching television | ||||

| At least once a week | 6027 | 31.0 (28.7 to 33.4) | Ref | Ref |

| Less than once a week | 3517 | 45.6 (42.2 to 48.9) | 1.87 (1.61 to 2.17) | 1.23 (1.07 to 1.41) |

| Never | 10 833 | 76.7 (74.8 to 78.5) | 7.35 (6.30 to 8.57) | 1.63 (1.41 to 1.88) |

| Knowledge of delivery complications | ||||

| Yes | 9032 | 33.8 (31.8 to 35.9) | Ref | Ref |

| None | 11 283 | 76.9 (75.0 to 78.6) | 6.50 (5.71 to 7.40) | 2.05 (1.83 to 2.29) |

| Enabling factor | ||||

| Seeking permission to visit health services | ||||

| Not a big problem | 17 865 | 55.1 (53.1 to 57.1) | Ref | Ref |

| Big problem | 2502 | 76.7 (72.5 to 80.4) | 2.68 (2.13 to 3.36) | 1.27 (1.09 to 1.47) |

| Getting money to pay health services | ||||

| Not a big problem | 11 410 | 52.5 (50.1 to 54.8) | Ref | Ref |

| Big problem | 8956 | 64.5 (62.1 to 66.8) | 1.65 (1.47 to 1.85) | 1.26 (1.14 to 1.39) |

| Distance to health facility | ||||

| Not a big problem | 13 907 | 51.0 (48.9 to 53.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Big problem | 6472 | 72.3 (69.7 to 74.9) | 2.52 (2.18 to 2.91) | 1.25 (1.12 to 1.40) |

| Wanting to be accompanied to health facility | ||||

| Not a big problem | 17 437 | 54.6 (52.7 to 55.6) | Ref | |

| Big problem | 2934 | 76.4 (73.4 to 79.1) | 2.69 (2.30 to 3.15) | |

| Behaviour of health workers | ||||

| Not a big problem | 16 928 | 55.4 (53.3 to 57.4) | Ref | Ref |

| Big problem | 3434 | 69.4 (66.4 to 72.1) | 1.82 (1.60 to 2.09) | 1.18 (1.03 to 1.36) |

| Need factor | ||||

| Contraceptive use | ||||

| Yes | 3260 | 26.8 (24.3 to 29.4) | Ref | Ref |

| No | 17 207 | 63.6 (61.8 to 65.5) | 4.78 (4.16 to 5.49) | 1.12 (0.98 to 1.28) |

| Wanted pregnancy at the time | ||||

| Wanted then | 18 368 | 59.5 (57.4 to 61.4) | Ref | |

| Wanted later | 1554 | 41.5 (38.2 to 44.8) | 0.48 (0.42 to 0.56) | |

| Unwanted | 444 | 40.0 (34.7 to 45.5) | 0.45 (0.36 to 0.57) | |

| Mother's perceived baby size at birth | ||||

| Large | 8996 | 54.6 (52.3 to 56.8) | Ref | Ref |

| Average | 8307 | 56.7 (54.2 to 59.2) | 1.09 (0.98 to 1.21) | 1.03 (0.97 to 1.15) |

| Small | 3026 | 69.4 (66.4 to 72.2) | 1.88 (1.64 to 2.16) | 1.41 (1.22 to 1.64) |

| Previous use of health services | ||||

| Delivery assistance | ||||

| Health professional | 8582 | 20.5 (18.9 to 22.2) | Ref | Ref |

| Non-health professional | 11 793 | 84.8 (83.2 to 86.2) | 21.1 (17.8 to 25.0) | 3.50 (2.88 to 4.27) |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Non-caesarean | 19 981 | 59.0 (57.0 to 60.9) | Ref | Ref |

| Caesarean section | 486 | 8.6 (6.2 to 11.7) | 1.44 (1.33 to 1.56) | 2.29 (1.61 to 3.27) |

| Place of delivery | ||||

| Health facility | 7649 | 17.3 (15.7 to 19.0) | Ref | Ref |

| Home | 12 780 | 81.9 (80.3 to 83.3) | 21.6 (18.6 to 25.1) | 4.51 (3.75 to 5.43) |

*Weighted prevalence of non-use of postnatal care as reported by mothers interviewed during the NDHS, 2013.

Increased odds of non-use of PNC services were observed among infants whose birth size was perceived as small at birth compared with large-sized infants (OR=1.41; CI 1.22 to 1.64). Mothers whose infants were delivered by non-health professionals had 3.5 times greater odds of not using PNC services than those infants who were delivered by health professionals. Other significant factors that were associated with non-use of PNC services included mothers whose infants were delivered at non-health facilities (OR=4.51; CI 3.75 to 5.43), and those whose deliveries occurred by caesarean section (OR=2.29; CI 1.61 to 3.27).

Out of the total PAR for non-use of PNC services, nearly 0.70 (PAR 0.68; CI 0.56 to 0.76) was attributable to infants who were delivered at non-health facilities (table 2). Our findings also showed that non-use of PNC was associated with infants whose mothers lacked knowledge of obstetric complications (PAR 0.37; CI 0.31 to 0.45) and those delivered by non-health professionals (PAR 0.61; CI 0.55 to 0.75).

Table 2.

Population attributable risk (PAR) for adjusted significant factors

| Variable | %† | Adjusted OR | PAR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Environmental factor | |||

| Residence type | |||

| Urban | 0.23 | 1.00 | – |

| Rural | 0.77 | 1.69 | 0.31 (0.21 to 0.39) |

| Sociodemographic factor | |||

| Household wealth index | |||

| Rich | 0.06 | 1.00 | – |

| Middle | 0.30 | 1.15 | 0.04 (0.02 to 0.24) |

| Poor | 0.64 | 1.66 | 0.26 (0.21 to 0.45) |

| Mother's education | |||

| Secondary or higher | 0.17 | 1.00 | – |

| Primary | 0.17 | 0.98 | n/a |

| No education | 0.66 | 1.37 | 0.18 (0.10 to 0.33) |

| Health knowledge | |||

| Frequency of watching television | |||

| At least once a week | 0.16 | 1.00 | – |

| Less than once a week | 0.14 | 1.23 | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.27) |

| Never | 0.70 | 1.63 | 0.27 (0.21 to 0.38) |

| Knowledge of delivery complications | |||

| Yes | 0.26 | 1.00 | – |

| None | 0.73 | 2.05 | 0.37 (0.31 to 0.45) |

| Enabling factor | |||

| Behaviour of health workers | |||

| Not a big problem | 0.79 | 1.00 | – |

| Big problem | 0.20 | 1.18 | 0.03 (0.02 to 0.25) |

| Need factor | |||

| Mother's perceived birth size | |||

| Large | 0.42 | 1.00 | – |

| Average | 0.40 | 1.03 | 0.01 (0.009 to 0.12) |

| Small | 0.18 | 1.41 | 0.05 (0.03 to 0.25) |

| Previous use of health services | |||

| Delivery assistance | |||

| Health professional | 0.15 | 1.00 | – |

| Non-health professional | 0.85 | 3.5 | 0.61 (0.55 to 0.75) |

| Place of delivery | |||

| Health facility | 0.11 | 1.00 | – |

| Home | 0.88 | 4.51 | 0.68 (0.56 to 0.76) |

†Proportion of mothers who did not use postnatal care services.

Discussion

Non-use of PNC services was used as the main outcome variable in this study. The main factors that posed risk to patronage of PNC services included the type of residence (rural or urban), household wealth, maternal education, mothers' knowledge of delivery-related complications, mothers' access to the mass media and perceived size of the baby at birth.

This study has several strengths that included the use of nationally representative data, with a relatively large sample size that yielded a high response rate (97.6%).6 The current findings are generalisable to the entire country since the demographic and health surveys are internationally validated and nationally adapted. Furthermore, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use nationally representative data to study the determinants of non-use of PNC services in Nigeria. There are, however, a number of limitations that are worthy of note when interpreting the results of this study. First, since this was a cross-sectional study, causal associations of the observed findings could not be clearly established. Second, variables available to measure the demographic, health knowledge and social structure factors were limited. Finally, the survey relied on retrospective information, which may have suffered a recall bias. However, such bias might not be problematic, as the study involved only mothers who gave birth within 5 years preceding the survey.

Living in a rural area was found in this study to be negatively associated with use of PNC services in Nigeria. This finding implied that use of PNC was associated with infants whose mothers lived in urban areas, which is consistent with a past study from Nepal.22 Generally, cultural practices are more prevalent in rural areas than in urban areas. PNC patronage is limited by the cultural tradition of keeping a newborn indoors, especially among mothers who give birth at home. Several other studies have reported this tradition of seclusion during the postnatal period.23 24 The finding can also be explained by the fact that in rural areas there is inadequate access to public services such as transportation, roads and health services, whereas urban dwellers are more likely to have access to adequate transportation and health services.25 Adequate physical accessibility to healthcare services has been found to increase maternal health utilisation as reported by past studies from Ghana26 and Nepal.27 Our findings support the need to provide PNC services, especially in rural areas, through alternative means, such as home visits by health professionals. The use of PNC services during the seclusion period when the mother and baby are confined to their room could be increased in communities by involving community leaders including religious leaders in health programmes.24 It may also be worthwhile to implement community-based newborn programmes to focus on providing home-based PNC services to mothers.28

One key finding of this study was that non-use of PNC services was significantly associated with infants from poor households. Using the household wealth index as a proxy indicator for the socioeconomic status of the household, mothers of low socioeconomic status were significantly less likely to use PNC services. This implied that mothers from rich households or of high socioeconomic status were significantly more likely to patronise PNC services. This finding is consistent with other past studies from India, Nepal and Nigeria,29–34 and can be explained by the availability of money to be able to pay for such healthcare services. The government of Nigeria and other stakeholders should look to make these maternal healthcare services affordable to mothers from low-income families.

There is evidence in the extant literature that mothers with higher levels of education are better informed about health risks and are more likely to demand and gain access to healthcare.31 34 Several past studies have highlighted the fact that use of PNC services was significantly associated with mothers with higher levels of education, implying that the risk of non-use of PNC services was higher among mothers with no schooling.27 35 36 This is similar to a finding in our study where mothers with no formal education were more likely not to access PNC services in Nigeria.

In this study, non-use of PNC services was found to be significantly higher among mothers who had limited or no access to the mass media. This is consistent with results from studies in Bangladesh37 and Indonesia.9 Limited or non-access to the mass media implies lack of exposure to information and health knowledge about pregnancy and PNC. Apart from entertainment, the mass media also inform and educate. Education and availability of information can help to enhance women's knowledge of the significance of health and increase women's confidence and improve their ability to seek appropriate healthcare services.38

Conclusions

This study reveals that the majority of Nigerian women did not use PNC services. Factors associated with this lack of patronage included household poverty, rural dwelling, poor maternal educational attainment and limited access to the mass media. The government of Nigeria and other non-governmental organisations should provide focused financial support to mothers from economically disadvantaged households in order to minimise the inequitable access to pregnancy and delivery healthcare services with trained healthcare personnel. Such an intervention could be complemented with community-based promotion programmes that would enhance awareness of the benefits of both pregnancy and PNC health services. Devices such as television sets and radios should be made affordable to women, especially those who reside in rural areas. Furthermore, the use of home visits by health professionals should also be implemented to ensure that those mothers living in remote areas are not further disadvantaged.

Footnotes

Contributors: KEA and OKE were involved in the conception and design of this study. KEA carried out the analysis. KEA and AII drafted the manuscript. OKE, AII, AIE, SB and AMNR provided advice on interpretation, and revised and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was based on an analysis of existing public domain survey data sets that is freely available online with all identifier information removed. The first author communicated with MEASURE DHS/ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA and was granted permission to download and use the data.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Ronsmans C, Graham WJ, Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet 2006;368:1189–200. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69380-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campbell OMR, Graham WJ. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet 2006;368:1284–99. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69381-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Where? Why? Lancet 2005;365:891–900. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. WHO technical consultation on postpartum and postnatal care. Geneva: WHO, 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Antenatal care: report of a technical working group. 31 October-4 November 1994 Geneva: World Health Organization, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Population Commission (NPC) [Nigeria] and ICF International. Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey 2013. Abuja, Nigeria, Rockville, Maryland, USA: NPC and ICF International, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chakraborty N, Islam MA, Chowdhury RI et al. . Utilisation of postnatal care in Bangladesh: evidence from a longitudinal study. Health Soc Care Community 2002;10:492–502. 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2002.00389.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Syed U, Asiruddin Sk, Helal MS et al. . Immediate and early postnatal care for mothers and newborns in rural Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 2006;24:508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Titaley CR, Dibley MJ, Roberts CL. Factors associated with non-utilisation of postnatal care services in Indonesia. J Epidemiol Community Health 2009;63:827–31. 10.1136/jech.2008.081604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khanal V, Lee AH, da Cruz JLNB et al. . Factors associated with non-utilisation of health service for childbirth in Timor-Leste: evidence from the 2009–2010 Demographic and Health Survey. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2014;14:14 10.1186/1472-698X-14-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Osubor KM, Fatusi AO, Chiwuzie JC. Maternal health-seeking behavior and associated factors in a rural Nigerian community. Matern Child Health J 2006;10:159–69. 10.1007/s10995-005-0037-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okafor CB. Availability and use of services for maternal and child health care in rural Nigeria. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1991;34:331–46. 10.1016/0020-7292(91)90602-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bawa S, Umar US, Onadeko M. Utilization of obstetric care services in a rural community in southwestern Nigeria. Afr J Med Med Sci 2004;33:239–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somefun OD, Ibisomi L. Determinants of postnatal care non-utilization among women in Nigeria. BMC Res Notes 2016;9:1–11. 10.1186/s13104-015-1823-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ezzati M, Lopez AD, Rodgers A et al. . Comparative Risk Assessment Collaborating Group. Selected major risk factors and global and regional burden of disease. Lancet 2002;360:1347–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11403-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav 1995;36:1–10. 10.2307/2137284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jahangir E, Irazola V, Rubinstein A. Need, enabling, predisposing, and behavioral determinants of access to preventative care in Argentina: analysis of the national survey of risk factors. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e45053 10.1371/journal.pone.0045053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amin R, Shah NM, Becker S. Socioeconomic factors differentiating maternal and child health-seeking behavior in rural Bangladesh: a cross-sectional analysis. Int J Equity Health 2010;9:9 10.1186/1475-9276-9-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabe-Hesketh S, Skrondal A. Multilevel modelling of complex survey data. J R Stat Soc Ser A (Statistics in Society) 2006;169:805–27. 10.1111/j.1467-985X.2006.00426.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC et al. . The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. Int J Epidemiol 1997;26:224–7. 10.1093/ije/26.1.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stafford RJ, Schluter PJ, Wilson AJ et al. . Population-attributable risk estimates for risk factors associated with Campylobacter infection, Australia. Emerging Infect Dis 2008;14:895–901. 10.3201/eid1406.071008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khanal V, Adhikari M, Karkee R et al. . Factors associated with the utilisation of postnatal care services among the mothers of Nepal: analysis of Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2011. BMC Womens Health 2014;14:19 10.1186/1472-6874-14-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawn J, Kerber K. Opportunities for Africa's newborns: practical data policy and programmatic support for newborn care in Africa. Cape Town, PMNCH, Save the Children, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winch PJ, Alam MA, Akther A et al. . Local understandings of vulnerability and protection during the neonatal period in Sylhet district, Bangladesh: a qualitative study. Lancet 2005;366:478–85. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66836-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrestha SK, Banu B, Khanom K et al. . Changing trends on the place of delivery: why do Nepali women give birth at home. Reprod Health 2012;9:25 10.1186/1742-4755-9-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doku D, Neupane S, Doku PN. Factors associated with reproductive health care utilization among Ghanaian women. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2012;12:29 10.1186/1472-698X-12-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neupane S, Doku DT. Determinants of time of start of prenatal care and number of prenatal care visits during pregnancy among Nepalese women. J Community Health 2012;37:865–73. 10.1007/s10900-011-9521-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pradhan YV, Upreti SR, Pratap KCN et al. . Newborn survival in Nepal: a decade of change and future implications. Health Policy Plan 2012;27 Suppl 3:iii57–71. 10.1093/heapol/czs052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dhakal S, Chapman GN, Simkhada PP et al. . Utilisation of postnatal care among rural women in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2007;7:19 10.1186/1471-2393-7-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neupane S, Doku D. Utilization of postnatal care among Nepalese women. Matern Child Health J 2013;17:1922–30. 10.1007/s10995-012-1218-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rahman MM, Haque SE, Zahan MS. Factors affecting the utilisation of postpartum care among young mothers in Bangladesh. Health Soc Care Community 2011;19:138–47. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00953.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jat TR, Ng N, San Sebastian M. Factors affecting the use of maternal health services in Madhya Pradesh state of India: a multilevel analysis. Int J Equity Health 2011;10:59 10.1186/1475-9276-10-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh PK, Rai RK, Alagarajan M et al. . Determinants of maternity care services utilization among married adolescents in rural India. PLoS ONE 2012;7:e31666 10.1371/journal.pone.0031666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Babalola S, Fatusi A. Determinants of use of maternal health services in Nigeria-looking beyond individual and household factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2009;9:43 10.1186/1471-2393-9-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simkhada B, Teijlingen ER, Porter M et al. . Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs 2008;61:244–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04532.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salam A, Siddiqui S. Socioeconomic inequalities in use of delivery care services in India. J Obstet Gynecol India 2006;56:123–7. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Islam M, Odland JO. Determinants of antenatal and postnatal care visits among Indigenous people in Bangladesh: a study of the Mru Community. Rural Remote Health 2011;11:1672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware H. Effects of maternal education, women's roles, and child care on child mortality. Popul Dev Rev 1984;10:191–214. 10.2307/2807961 [DOI] [Google Scholar]