Abstract

Objectives

Evidence to guide fluid resuscitation evidence in sepsis continues to evolve. We conducted a multicountry survey of emergency and critical care physicians to describe current stated practice and practice variation related to the quantity, rapidity and type of resuscitation fluid administered in early septic shock to inform the design of future septic shock fluid resuscitation trials.

Methods

Using a web-based survey tool, we invited critical care and emergency physicians in Canada, the UK, Scandinavia and Saudi Arabia to complete a self-administered electronic survey.

Results

A total of 1097 physicians’ responses were included. 1 L was the most frequent quantity of resuscitation fluid physicians indicated they would administer at a time (46.9%, n=499). Most (63.0%, n=671) stated that they would administer the fluid challenges as quickly as possible. Overall, normal saline and Ringer's solutions were the preferred crystalloid fluids used ‘often’ or ‘always’ in 53.1% (n=556) and 60.5% (n=632) of instances, respectively. However, emergency physicians indicated that they would use normal saline ‘often’ or ‘always’ in 83.9% (n=376) of instances, while critical care physicians said that they would use saline ‘often’ or ‘always’ in 27.9% (n=150) of instances. Only 1.0% (n=10) of respondents indicated that they would use hydroxyethyl starch ‘often’ or ‘always’; use of 5% (5.6% (n=59)) or 20–25% albumin (1.3% (n=14)) was also infrequent. The majority (88.4%, n=896) of respondents indicated that a large randomised controlled trial comparing 5% albumin to a crystalloid fluid in early septic shock was important to conduct.

Conclusions

Critical care and emergency physicians stated that they rapidly infuse volumes of 500–1000 mL of resuscitation fluid in early septic shock. Colloid use, specifically the use of albumin, was infrequently reported. Our survey identifies the need to conduct a trial on the efficacy of albumin and crystalloids on 90-day mortality in patients with early septic shock.

Keywords: Septic shock, Fluid resuscitation, Survey, Adults, Critical Care, Emergency Medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This survey included a large sample of emergency and critical care physicians’ stated early septic shock resuscitation practices from Canada, the UK, Scandinavia and Saudi Arabia.

The survey was designed to be short, simple and specific to the early resuscitative phase of septic shock so that it would take at most 5 min to complete.

Since the survey focused on the early resuscitative phase of septic shock, the responses to questions may not be generalisable to later phases of septic shock or specific subpopulations of patients with septic shock.

Owing to the variable methods used for survey distribution, we could not summarise an accurate response proportion.

Background

Fluid resuscitation is a vital first-line intervention for all patients with septic shock. Management guidelines recommend rapid administration of resuscitation fluid to achieve a minimum of 30 mL/kg in the early hours of resuscitation, with the goal of regaining haemodynamic stability, optimising organ perfusion and ultimately improving outcomes and preventing death.1 While fluid resuscitation is a life-saving intervention, until recently, high-quality evidence to guide fluid choice and resuscitation practices has been lacking.

In recent years, there has been an accumulation of evidence regarding fluid resuscitation that has served both to change practice and prompt further resuscitation research questions. For example, a multicentre paediatric trial from East Africa of predominantly malaria-infected children with severe fever and hypoperfusion questioned how aggressively we should administer resuscitation fluids in this setting.2 This trial found that fluid boluses, as compared with the administration of intravenous maintenance fluids, increased the risk of death at 48 hours. The results of these research findings have encouraged other investigators to further study aggressive versus conservative fluid resuscitation strategies for children and adults with septic shock in the emergency department (ED) and intensive care unit and clinical trials are ongoing or recently completed (Clinical Trials.gov NCT02079402 and NCT01973907, respectively). Evidence has also emerged to help guide practice with regard to the use of colloid fluids in sepsis. In 2004, our group conducted a survey of early septic shock resuscitation practices of Canadian critical care physicians and found that hydroxyethyl starch (HES) fluid was used commonly, reportedly 51% of the time.3 An international cross-sectional study of fluid resuscitation episodes in the intensive care unit conducted in 2007 also documented frequent colloid fluid use (48% of episodes) and 44% of colloids administered were HES fluids.4 Since the publication of these studies, data from randomised trials and systematic reviews have demonstrated clear harms caused by HES in critically ill patients, particularly those with sepsis.5–9 Although a recent systematic review of albumin in sepsis found no overall mortality benefit,10 two subgroup analyses from recent randomised trials comparing albumin to crystalloid fluid in the critically ill and severe sepsis and septic shock found reductions in mortality at 28 and 90 days, respectively.11 12

In the context of evolving literature to guide practice, we conducted an early septic shock fluid resuscitation survey to inform the design and provide justification for future early septic shock fluid resuscitation trials comparing 5% albumin versus crystalloid fluid on 90-day mortality. Our survey had two objectives: (1) to describe practice variation among emergency and critical care physicians regarding the quantity, rapidity and type of fluid administered during early septic shock resuscitation and (2) to elicit views of a future early septic shock fluid resuscitation trial comparing 5% albumin versus crystalloid fluid on 90-day mortality by eliciting from respondents the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) between fluid intervention and control arms that would inform their practice, as well understanding the perceived importance of and respondents’ willingness to enrol into such a future trial.

Methods

Identification of study participants and survey distribution

Our target population consisted of critical care and emergency physicians in Canada, the UK, Scandinavia and Saudi Arabia who provide care for adult patients (≥18 years of age) with septic shock. These countries were selected because research and opinion leaders in these countries had expressed interest in collaborating on an international trial on early fluid resuscitation.

Participants were contacted by their respective critical care or emergency medicine professional societies in the UK and Canada, and through direct contact with lead site investigators in Canada, Scandinavia (including the countries Norway, Sweden, Finland and Denmark) and Saudi Arabia using a standardised email containing a weblink to the survey. Respondents activated the weblink and completed the survey instrument online. The survey was distributed in January and February 2014. To maximise responses, non-respondents received up to two email reminders.

Survey development

We generated items for the survey instrument through literature review and consultation with international investigators representing emergency and critical care medicine. Items were reduced and formatted to reduce respondent burden and maximise the response rate. The survey was pilot tested by our investigative team and critical care research fellows at the University of Ottawa in Ottawa, Canada, for clinical sensibility and with a target time to completion of 5 min. The survey was structured using a web-based survey platform (FluidSurveys). Research ethics board approval was sought as required by lead investigators for each country that participated in the survey.

Survey content

The survey presented a typical patient with early septic shock in the ED (see survey, online supplementary appendix 1). This patient was introduced as a 55-year-old 70 kg female who had just arrived in the ED with suspected septic shock. She was confused, with a blood pressure of 70/30, heart rate 135 bpm, respiratory rate of 25 breaths per minute, temperature 39.5°C and oxygen saturation of 96% on 3 L by nasal prongs. She had already received a total of 1 L of normal saline over 15 min in the ED.

bmjopen-2015-010041supp.pdf (734.5KB, pdf)

Respondents were then asked a series of questions: the first was to document the quantity and rapidity of fluid administration, and the second question examined the type of resuscitation fluids that they would use in a ‘typical’ and an ‘ideal’ situation to resuscitate the patient described above. An ‘ideal’ situation was proposed for respondents to ascertain the fluid type given that a physician may wish to give a fluid, but that fluid may not be readily available to them in practice (eg, fluid not stocked or immediately available in the department). For each of these questions, respondents answered on the basis of a five-point Likert scale (ie, never, rarely, sometimes, often, always). For the type of resuscitation fluid question (survey questions 2a and 2b), Ringer's solutions (ie, Ringer's lactate, Ringer's acetate and Hartmann's solutions) were bundled together as one response option, reflecting their biochemical similarity13 and reducing respondent question burden.

To inform the design of an early septic shock fluid resuscitation trial comparing 5% albumin to a crystalloid fluid on the primary outcome of 90-day mortality, we asked respondents to provide their views on an estimate of the MCID between the fluid intervention and control arms that would be required to inform their practice (response options: 1%, 2.5%, 5%, 7.5% and 10%). Two further questions were posed to determine the perceived importance of (response options: not at all important, not very important, somewhat important, important, very important) and their willingness to enrol patients into such a trial (response options: yes, no).

We also documented respondents’ primary specialty and their practice experience in emergency medicine and/or critical care.

Survey data collection and analysis

All data were collected electronically through FluidSurveys (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) and were housed and managed on FluidSurveys’ secure servers. Prior to analysis, raw data were exported to Microsoft Excel (V.2010, Redmond, Washington, USA) for cleaning and then exported to SAS (V.9.2, by SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA) for analysis.

All data are presented with numbers and proportions for dichotomous and categorical variables, and with means and SDs or medians and IQRs for continuous variables, as appropriate. Missing responses were not imputed. The five-point Likert scale responses were combined into ‘often or always’, ‘sometimes’ and ‘rarely or never’ for purposes of data presentation. The data for all respondents were also described according to whether respondents were critical care or emergency medicine physicians. No sample size calculation was conducted a priori since main survey intent was to be descriptive. Post hoc, we calculated absolute differences (ADs) in proportions and 95% CIs between typical and ideal fluid use for all respondents and by primary specialty (critical care physicians and emergency physicians), respectively. Differences in proportions with 95% CIs for emergency and critical care physicians for typical and ideal fluid were also calculated.

Results

Study sample

A total of 1139 physicians responded to the survey; 16 respondents were not emergency or critical care physicians, a further 15 did not provide care for adult patients with septic shock, and 11 physicians did not respond to one (n=10) or both (n=1) of these questions. Thus, a total of 1097 physicians’ responses were included in the final results. Of these, 64% (n=702) were from the UK, 26% (n=290) were from Canada and the remaining 10% (n=105) were from Saudi Arabia (6.6%, n=72) and Scandinavia (3.0%, n=33).

Demographics and training

A total of 90% (n=985) of physicians responded to the primary specialty question. Of these responses, 45.5% (n=448) of physicians indicated that their primary specialty was emergency medicine. The average number of years spent in clinical practice was 10 (SD=8).

Quantity and rapidity of administration of resuscitation fluids

When we asked physicians about the quantity of resuscitation fluid that they would typically administer at a time to our hypothetical patient with early septic shock in the ED, the most common answer was 1 L of fluid (46.9%, n=499), followed by 500 mL (32.0%, n=340; see table 1). When examined by primary specialty, 1 L (62.3%, n=279) and 500 mL (41.5%, n=223) were the most frequent responses for emergency and critical care physicians, respectively. Most physicians (63%, n=671) stated that they would administer the fluid challenges as quickly as possible; this response remained the most frequent when the data were examined by emergency and critical care physicians (73.2%, n=328 and 56.4%, n=303, respectively).

Table 1.

Quantity and rapidity of fluid resuscitation by all respondents, critical care and emergency physicians

| Quantity n (%) |

Rapidity n (%) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=1064) |

(n=1065) |

||

| All respondents | |||

| 100 mL | 2 (0.2) | 5 min | 66 (6.2) |

| 250 mL | 123 (11.6) | 10 min | 98 (9.2) |

| 500 mL | 340 (32.0) | 15 min | 131 (12.3) |

| 750 mL | 9 (0.8) | 30 min | 81 (7.6) |

| 1000 mL | 499 (46.9) | 1 hour | 18 (1.7) |

| Other | 91 (8.6) | As quickly as possible | 671 (63.0) |

| (n=537) | (n=537) | ||

| Critical care physicians | |||

| 100 mL | 2 (0.4) | 5 min | 45 (8.4) |

| 250 mL | 86 (16.0) | 10 min | 64 (11.9) |

| 500 mL | 223 (41.5) | 15 min | 75 (14.0) |

| 750 mL | 6 (1.1) | 30 min | 42 (7.8) |

| 1000 mL | 194 (36.1) | 1 hour | 8 (1.5) |

| Other | 26 (4.8) | As quickly as possible | 303 (56.4) |

| (n=448) | (n=448) | ||

| Emergency physicians | |||

| 100 mL | 0 (0) | 5 min | 12 (2.7) |

| 250 mL | 21 (4.7) | 10 min | 25 (5.6) |

| 500 mL | 90 (20.1) | 15 min | 43 (9.6) |

| 750 mL | 3 (0.7) | 30 min | 35 (7.8) |

| 1000 mL | 279 (62.3) | 1 hour | 5 (1.1) |

| Other | 55 (12.3) | As quickly as possible | 328 (73.2) |

Type of resuscitation fluid typically and ideally administered

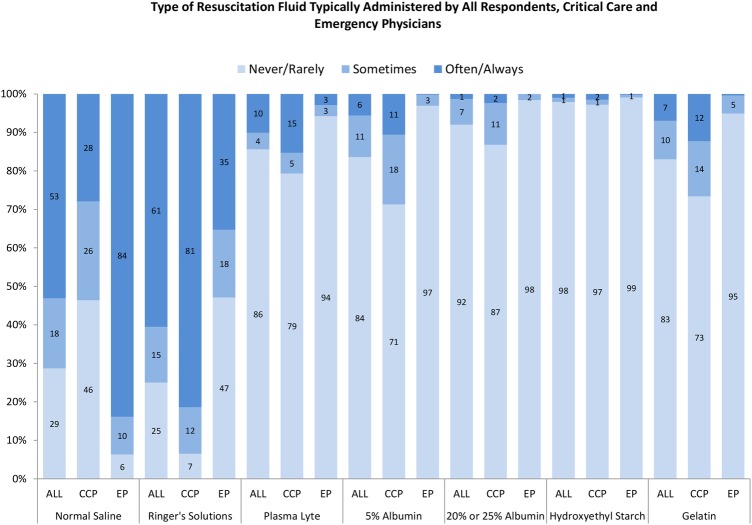

Normal saline and Ringer’s solutions were used typically ‘often’ or ‘always’ for early septic shock resuscitation 53.1% (n=556) and 60.5% (n=632) of the time, respectively (see figure 1 and table 2). In contrast, respondents infrequently used Plasma-Lyte (10.1%, n=106), 5% albumin (5.6%, n=59), 20–25% albumin (1.3%, n=14) and gelatin (7.0%, n=73) ‘often’ or ‘always’ in early resuscitative efforts. Only 1.0% (n=10) of respondents indicated that they would use HES ‘often’ or ‘always’ in the resuscitative phase of septic shock.

Figure 1.

The Y-axis depicts the proportion of respondents that answered never/rarely, sometimes or often/always to each typical resuscitation fluid type. The X-axis includes each typical resuscitation fluid type according to all respondents, emergency physicians and critical care physicians. The response for Ringer's solutions could reflect typical use of Ringer's lactate, Ringer's acetate or Hartmann's solutions, since these solutions were bundled into one response option in survey question 2a. ALL, all respondents; CCP, critical care physicians; EP, emergency physicians.

Table 2.

Type of resuscitation fluid typically and ideally administered by all respondents, critical care and emergency physicians

| Typically administered |

Ideally administered |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Never/rarely | Sometimes | Often/always | Number | Never/rarely | Sometimes | Often/always | |

| Type | Respondents | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | Respondents | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| All respondents | ||||||||

| Normal saline | (n=1047) | 300 (28.7) | 191 (18.2) | 556 (53.1) | (n=1045) | 384 (36.7) | 165 (15.8) | 496 (47.5) |

| Ringer's solutions | (n=1045) | 261 (25.0) | 152 (14.5) | 632 (60.5) | (n=1044) | 232 (22.2) | 141 (13.5) | 671 (64.3) |

| Plasma-Lyte | (n=1045) | 894 (85.6) | 45 (4.3) | 106 (10.1) | (n=1043) | 716 (68.7) | 63 (6.0) | 264 (25.3) |

| 5% albumin | (n=1045) | 873 (83.5) | 113 (10.8) | 59 (5.6) | (n=1044) | 740 (70.9) | 175 (16.8) | 129 (12.4) |

| 20% or 25% albumin | (n=1044) | 960 (92.0) | 70 (6.7) | 14 (1.3) | (n=1043) | 911 (87.3) | 101 (9.7) | 31 (3.0) |

| Hydroxyethyl starch | (n=1044) | 1023 (98.0) | 11 (1.1) | 10 (1.0) | (n=1044) | 1017 (97.4) | 15 (1.4) | 12 (1.1) |

| Gelatin | (n=1045) | 868 (83.1) | 104 (10.0) | 73 (7.0) | (n=1044) | 903 (86.5) | 82 (7.9) | 59 (5.7) |

| Critical care physicians | ||||||||

| Normal saline | (n=537) | 249 (46.4) | 138 (25.7) | 150 (27.9) | (n=537) | 300 (55.9) | 114 (21.2) | 123 (22.9) |

| Ringer's solutions | (n=537) | 35 (6.5) | 65 (12.1) | 437 (81.4) | (n=537) | 51 (9.5) | 56 (10.4) | 430 (80.1) |

| Plasma-Lyte | (n=537) | 426 (79.3) | 29 (5.4) | 82 (15.3) | (n=537) | 297 (55.3) | 44 (8.2) | 196 (36.5) |

| 5% albumin | (n=537) | 383 (71.3) | 97 (18.1) | 57 (10.6) | (n=537) | 310 (57.7) | 117 (21.8) | 110 (20.5) |

| 20% or 25% albumin | (n=537) | 466 (86.8) | 58 (10.8) | 13 (2.4) | (n=537) | 442 (82.3) | 71 (13.2) | 24 (4.5) |

| Hydroxyethyl starch | (n=537) | 522 (97.2) | 7 (1.3) | 8 (1.5) | (n=537) | 521 (97.0) | 7 (1.3) | 9 (1.7) |

| Gelatin | (n=537) | 394 (73.4) | 77 (14.3) | 66 (12.3) | (n=537) | 426 (79.3) | 58 (10.8) | 53 (9.9) |

| Emergency physicians | ||||||||

| Normal saline | (n=448) | 28 (6.3) | 44 (9.8) | 376 (83.9) | (n=448) | 61 (13.6) | 41 (9.2) | 346 (77.2) |

| Ringer's solutions | (n=448) | 211 (47.1) | 79 (17.6) | 158 (35.3) | (n=448) | 170 (37.9) | 76 (17.0) | 202 (45.1) |

| Plasma-Lyte | (n=448) | 422 (94.2) | 13 (2.9) | 13 (2.9) | (n=448) | 381 (85.0) | 16 (3.6) | 51 (11.4) |

| 5% albumin | (n=448) | 434 (96.9) | 13 (2.9) | 1 (0.2) | (n=448) | 384 (85.7) | 47 (10.5) | 17 (3.8) |

| 20% or 25% albumin | (n=448) | 441 (98.4) | 7 (1.6) | 0 (0) | (n=448) | 423 (94.4) | 20 (4.5) | 5 (1.1) |

| Hydroxyethyl starch | (n=448) | 444 (99.1) | 3 (0.7) | 1 (0.2) | (n=448) | 437 (97.5) | 8 (1.8) | 3 (0.7) |

| Gelatin | (n=448) | 425 (94.9) | 21 (4.7) | 2 (0.4) | (n=448) | 424 (94.6) | 21 (4.7) | 3 (0.7) |

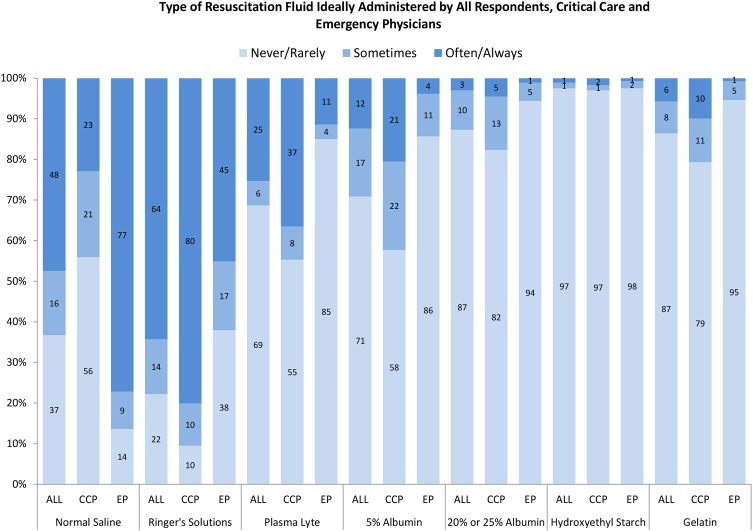

When asked about the use of these fluids in the ideal setting where they would be immediately available, use of Plasma-Lyte and 5% albumin ‘often’ or ‘always’ increased the most (Plasma-Lyte from 10.1% (n=106) to 25.3% (n=264; AD=−15.2%; 95% CI −17.5% to −12.9%) and 5% albumin from 5.6% (n=59) to 12.4% (n=129; AD=−6.7%; 95% CI −8.3% to −5.0%; see figure 2 and online supplementary table S1)).

Figure 2.

The Y-axis depicts the proportion of respondents that answered never/rarely, sometimes or often/always to each ideal resuscitation fluid type. The X-axis includes each ideal resuscitation fluid type according to all respondents, emergency physicians and critical care physicians. The response for Ringer's solutions could reflect ideal use of Ringer's lactate, Ringer's acetate or Hartmann's solutions since these solutions were bundled into one response option in survey question 2b. ALL, all respondents; CCP, critical care physicians; EP, emergency physicians.

When the typical use of crystalloid fluids was examined by primary specialty, emergency physicians indicated that they would use normal saline ‘often’ or ‘always’ 83.9% (n=376), in contrast to critical care physicians, who said that they would use saline 27.9% (n=150; AD=56.0%; 95% CI 50.9% to 61.1%; see figure 1 and online supplementary table S1). In the ideal setting, where these fluids would be immediately available, the two fluid-type responses that increased the most for emergency physicians were Ringer’s solutions from 35.3% (n=158) to 45.1% (n=202; AD=−9.8; 95% CI −13.3 to −6.4) and Plasma-Lyte from 2.9% (n=13) to 11.4% (n=51; AD=−8.5; 95% CI −11.2 to −5.8; see figure 2, online supplementary table S1). The two fluid-type responses that increased the most in the ideal setting for critical care physicians were Plasma-Lyte (from 15.3% (n=82) to 36.5% (n=196), AD=−21.2; 95% CI −24.9 to −17.6) and 5% albumin (from 10.6% (n=57) to 20.5% (n=110), AD=−9.9; 95% CI −12.6 to −7.1).

A summary of typical and ideal fluid use by country is provided in online supplementary table S2 and figures S1 and S2, respectively.

Views on a future early septic shock fluid resuscitation trial

Most respondents indicated that the MCID for a future trial comparing 5% albumin and a crystalloid fluid on 90-day mortality for early septic shock that would be required to maintain or change their practice was 5% (53.6%, 539/1005). Respondents also indicated that a large randomised controlled trial comparing 5% albumin to a crystalloid fluid with a primary outcome of 90-day mortality was important to conduct as 88.4% (896/1014) of respondents indicated that the trial was somewhat important (24.0%, 243/1014), important (39.4%, 400/1014) or very important (25%, 253/1014). Furthermore, 84.4% (851/1008) of respondents indicated that they would be willing to enrol patients into such a future clinical trial.

Discussion

Results of our multicountry survey suggest that emergency and critical care physicians who assess and manage adult patients in the early resuscitative phase of septic shock prefer that fluid challenges (at least 500 mL) be administered as quickly as possible. When examined by primary specialty, critical care physicians indicated a preference to use Ringer’s solutions compared with emergency physicians who indicated a preference to use normal saline. Although the reported use of Plasma-Lyte was infrequent, our survey data suggest that both emergency and critical care physicians would use more of this crystalloid fluid if it was readily available to them. Use of HES fluid was uncommon and the reported use of albumin (5% or 20–25%) was infrequent, although critical care physicians also indicated that they would use albumin more frequently if it was immediately available to them.

An abundance of observational evidence from large propensity-matched cohort studies in the surgical14 15 and critically ill16 populations, and a prospective sequential period study17 in the critically ill suggest that high-chloride fluids (eg, normal saline) may be associated with excess mortality compared with lower chloride fluids such as Ringer’s solutions or Plasma-Lyte. In addition, normal saline resuscitation has been associated with the subsequent use of renal replacement therapy, increased postoperative infections and prolonged length of stay in hospital.14–17 A recently published pilot trial examined normal saline versus Plasma-Lyte for fluid resuscitation in the intensive care unit.18 Investigators did not detect an increased risk of acute kidney injury or failure, or an increased risk of requirement for renal replacement therapy with normal saline. However, the study was underpowered for these clinical outcomes and a larger trial with death as the primary end point is now planned (NCT02721654). Both our survey and a similar survey conducted in Scotland19 suggest that emergency physicians prefer using normal saline, while critical care physicians prefer Ringer’s solutions in septic shock. The variability in stated practice between emergency and critical care physicians that was evident in our survey may reflect an absence of high-quality evidence to support the preference of either of these fluids, although a recent network meta-analysis of randomised controlled fluid trials in sepsis found that balanced crystalloids such as Ringer’s or Plasma-Lyte as compared with normal saline were associated with a reduced odds of death.20 However, since the reported use of Ringer’s solutions and Plasma-Lyte further increased when presented with an ‘ideal’ but still theoretical scenario in our survey, lack of availability of these fluids or unit-specific policies or protocols21 may contribute to the reported practice variability we identified.

Very few emergency and critical care physicians indicated that they would use HES boluses in the early resuscitative phase of septic shock. This contrasts sharply to a septic shock resuscitation survey from 2004 in which Canadian critical care physicians reported that they would use HES fluids for early septic shock resuscitation 51% of the time. In the European intensive care unit fluid challenge observational study conducted in 2013, HES use accounted for only 10.8% of all fluid challenges in the study.21 This apparent change in practice is most likely related to high-quality evidence from randomised controlled trials and systematic reviews in the past decade that now confirm that starch fluids increase the risk of death and the use of renal replacement therapy in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock.6 7 9

According to our survey results, the use of albumin in the early septic shock setting also remains infrequent despite the SAFE (A Comparison of Albumin to Saline for Fluid Resuscitation in the Intensive Care Unit) severe sepsis subgroup analysis that suggested that 4% albumin compared with normal saline was associated with a significant reduction in 28-day mortality. After the conduct of this survey in 2014, the ALBIOS trial (Albumin Replacement for Patients with Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock) which compared 20% albumin with crystalloids versus crystalloids alone for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock was published. The ALBIOS trial found a mortality benefit at 90 days for 20% albumin in a post hoc analysis of patients with septic shock but not in those with severe sepsis.12 If practice was influenced by that trial, it is possible that the albumin responses in our survey under-represent current use in early septic shock.

This survey has several weaknesses. A denominator could not be calculated to ascertain a response proportion because of the variable methods we used to distribute the survey. Although we obtained responses from ∼1000 critical care and emergency medicine physicians from Canada, the UK, Saudi Arabia and Scandinavia, we cannot confirm that the responses generated are representative of the countries or regions. Resuscitation questions were asked in relation to one hypothetical early septic shock scenario and, as such, it is not possible to comment on fluid resuscitation practices, according to physician characteristics, for patients in the later phase of septic shock or with specific physiological characteristics (eg, hypoalbuminaemia), or chronic morbidities. However, this survey was large (∼1000 responses), and it includes the stated preferences of critical care and emergency medicine physicians, which are divergent with regard to the quantity and type of resuscitation fluid used for early septic shock resuscitation. Although answers to questions related to other aspects of septic shock management were not obtained, they provide robust information regarding the fluid resuscitation practices of a wide variety of physicians managing patients in the early resuscitative phase of septic shock. Furthermore, the survey was designed to be brief and take <5 min to complete to maximise responses to each question. That goal was achieved, since at least 95% of respondents answered each of the resuscitation questions.

In summary, in the resuscitative phase of septic shock, emergency and critical care physician practices as stated in this survey are to administer volumes of resuscitation fluid most commonly in the range of 500–1000 mL at a time. It is important to note that these volumes are within the current surviving sepsis resuscitation guidelines that recommend a minimum achievement of 30 mL/kg in the early hours of resuscitation since our aim was to elicit details of how much bolused resuscitation fluid would be administered at a time during early septic shock.1 Although normal saline and Ringer’s solutions are the two most common crystalloid fluids, stated preferences differ between emergency and critical care physicians. Most physicians support a future trial of albumin compared with crystalloid fluid in the early phase of septic shock.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Canadian Critical Care Society, the Intensive Care Foundation (UK), the Royal College of Emergency Medicine (UK) and the King Abdullah International Medical Research Centre for their assistance in contacting emergency and critical care physicians through their respective membership lists. BHR is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) as a Tier I Canada Research Chair in Evidence-based Emergency Medicine through the Government of Canada (Ottawa, Ontario, Canada). AT and RZ are recipients of CIHR new investigator awards, SMB is supported by CIHR as a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Critical Care Nephrology and DC is supported by CIHR as a Tier II Canada Research Chair in Critical Care. The authors would like to thank Francois Lauzier from the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group for a critical review of this manuscript, Tinghua Zhang from the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (OHRI) for collating the data and performing the statistical analyses, the Centre for Transfusion Research at the OHRI for their in-kind study support, and Marnie Gordon for her administrative support.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Anthony Gordon at @agordonICU

Contributors: LM, DF, BHR, TSW, AG, AP, YA and JM conceived the survey design. LM drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to interpretation of the data and critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors have given permission to submit this manuscript for publication.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: FluidSurveys’ involvement in the project was limited to providing the secure platform that allowed the research team to collect data. AP has received grant support from CSL Behring and Fresenius Kabi and LM has received grant support from CSL Behring, all of which is outside of this submitted work. SMB has consulted for Baxter Healthcare Corp.

Ethics approval: Ottawa Health Sciences Network Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al. . Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 2013;39:165–228. 10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO et al. . Mortality after fluid bolus in African children with severe infection. N Engl J Med 2011;364:2483–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa1101549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McIntyre LA, Hébert PC, Fergusson D et al. . A survey of Canadian intensivists’ resuscitation practices in early septic shock. Crit Care 2007;11:R74 10.1186/cc5962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finfer S, Liu B, Taylor C et al. . Resuscitation fluid use in critically ill adults: an international cross-sectional study in 391 intensive care units. Crit Care 2010;14:R185 10.1186/cc9293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myburgh JA, Finfer S, Bellomo R et al. . Hydroxyethyl starch or saline for fluid resuscitation in intensive care. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1901–11. 10.1056/NEJMoa1209759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perner A, Haase N, Guttormsen AB et al. . Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.42 versus Ringer's acetate in severe sepsis. N Engl J Med 2012;367:124–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1204242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haase N, Perner A, Hennings LI et al. . Hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.38-0.45 versus crystalloid or albumin in patients with sepsis: systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. BMJ 2013;346:f839 10.1136/bmj.f839 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gattas DJ, Dan A, Myburgh J et al. . Fluid resuscitation with 6% hydroxyethyl starch (130/0.4) in acutely ill patients: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2012;114:159–69. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318236b4d6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarychanski R, Abou-Setta AM, Turgeon AF et al. . Association of hydroxyethyl starch administration with mortality and acute kidney injury in critically ill patients requiring volume resuscitation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2013;309:678–88. 10.1001/jama.2013.430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel A, Laffan MA, Waheed U et al. . Randomised trials of human albumin for adults with sepsis: systematic review and meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis of all-cause mortality. BMJ 2014;349:g4561 10.1136/bmj.g4561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finfer S, McEvoy S, Bellomo R et al. . Impact of albumin compared to saline on organ function and mortality of patients with severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med 2011;37:86–96. 10.1007/s00134-010-2039-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caironi P, Tognoni G, Masson S et al. . Albumin replacement in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock. N Engl J Med 2014;370:1412–21. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddy S, Weinberg L, Young P et al. . Crystalloid fluid therapy. Crit Care 2016;20:59 10.1186/s13054-016-1217-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shaw AD, Bagshaw SM, Goldstein SL et al. . Major complications, mortality, and resource utilization after open abdominal surgery: 0.9% saline compared to Plasma-Lyte. Ann Surg 2012;255:821–9. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825074f5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCluskey SA, Karkouti K, Wijeysundera D et al. . Hyperchloremia after noncardiac surgery is independently associated with increased morbidity and mortality: a propensity-matched cohort study. Anesth Analg 2013;117:412–21. 10.1213/ANE.0b013e318293d81e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raghunathan K, Shaw A, Nathanson B et al. . Association between the choice of IV crystalloid and in-hospital mortality among critically ill adults with sepsis*. Crit Care Med 2014;42:1585–91. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yunos NM, Bellomo R, Hegarty C et al. . Association between a chloride-liberal vs chloride-restrictive intravenous fluid administration strategy and kidney injury in critically ill adults. JAMA 2012;308:1566–72. 10.1001/jama.2012.13356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young P, Bailey M, Beasley R et al. , SPLIT Investigators; ANZICS CTG. Effect of a buffered crystalloid solution vs saline on acute kidney injury among patients in the intensive care unit: the SPLIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2015;314:1701–10. 10.1001/jama.2015.12334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiwaji Z, Brady S, McIntyre LA et al. . Emergency department management of early sepsis: a national survey of emergency medicine and intensive care consultants. Emerg Med J 2014;31:1000–5. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rochwerg B, Alhazzani W, Sindi A et al. . Fluid resuscitation in sepsis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:347–55. 10.7326/M14-0178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cecconi M, Hofer C, Teboul JL et al. , ESICM Trial Group. Fluid challenges in intensive care: the FENICE study: a global inception cohort study. Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1529–37. 10.1007/s00134-015-3850-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010041supp.pdf (734.5KB, pdf)