Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate the short-term and long-term prognostic impacts of acute phase coronary collaterals to occluded infarct-related arteries (IRA) after ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in the percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) era.

Design

A prospective observational study.

Setting

Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study (OACIS) in Japan.

Participants

3340 patients with STEMI from the OACIS database who were admitted to hospitals within 24 hours from the onset and who had a completely occluded IRA.

Interventions

Patients were divided into 4 groups according to the Rentrop collateral score (RCS) by angiography on admission (RCS-0, no visible collaterals; RCS-1, collaterals without IRA filling; RCS-2, collaterals with partial IRA filling; and RCS-3, collaterals with complete IRA filling).

Primary outcome measures

In-hospital and 5-year mortality.

Results

Patients with RCS-0/3 were older than patients with RCS-1/2, and the prevalence of previous myocardial infarction was highest in patients with RCS-3. Median peak creatinine phosphokinase levels decreased as RCS increases (p<0.001), suggesting the acute cardioprotective effects of collaterals. Although RCS-1 and RCS-2 collaterals were associated with better in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR 0.48, p=0.046 and 0.38, p=0.010 for RCS-1 and RCS-2, respectively) and 5-year mortality (adjusted HR 0.53, p=0.004 and 0.46, p<0.001 for RCS-1 and RCS-2, respectively) as compared with R-0, presence of RCS-3 collaterals was not associated with improved in-hospital (adjusted OR 1.35, p=0.331) and 5-year mortality (adjusted HR 0.98, p=0.920), possibly because worse clinical profiles in patients with RCS-3 may mask mortality benefit of coronary collaterals.

Conclusions

Presence of acute phase coronary collaterals such as RCS-1 and RCS-2 were associated with better in-hospital and 5-year mortality after STEMI in the contemporary PCI era.

Keywords: ST-elevation myocardial infarction, Coronary collateral, Mortality, Percutaneous coronary intervention

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Our study has one of the largest study populations published until now, which allowed us to evaluate the impact of coronary collaterals among four Rentrop collateral categories.

We evaluated the impact of coronary collaterals on both in-hospital and 5-year mortality.

There may be a selection bias because we only focused on patients who visited hospitals within 24 hours from the onset and who underwent emergent coronary angiography, and it is not clear whether identical conclusions can be drawn for all patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

Introduction

Coronary collaterals provide an alternative source of blood supply to the ischaemic myocardium.1–3 In patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI), collaterals to the infarct-related arteries (IRA) are angiographically observed in ∼40%,4 providing myocardial protective effects such as improved functional recovery,5 infarct size reduction,6 7 prevention of no-reflow phenomenon8 or prevention of ventricular aneurysm formation.9 Furthermore, coronary collaterals that develop after the convalescent stage of AMI were associated with prevention of subsequent ventricular remodelling.10 However, some controversies have arisen regarding the long-term beneficial impacts of coronary collaterals in patients with AMI in the contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) era.11–18 Recently, many large-scale studies and their meta-analysis revealed no association between coronary collaterals and long-term mortality after AMI.13–17 One of the possible reasons for this discrepancy is that the definition of significant collaterals differed among the studies. For example, minimal collaterals such as Rentrop grade 1 collaterals were sometimes classified as non-significant collaterals. In addition, several studies did not exclude patients with patent IRA. In such studies, interpretation of the results were complicated and difficult because antegrade flow of IRA was likely to have counteracted with coronary collateral flow resulting in underestimation of collateral flow grades.13–17 Thus, comprehensive analyses in a large-scale cohort are now warranted so that investigators can evaluate the cardioprotective impacts of coronary collaterals in detail by selecting patients with completely occluded IRA.

In the present study, we sought to investigate the impacts of acute phase coronary collaterals on in-hospital and 5-year mortality enrolling 3340 patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) with completely occluded IRA from the database of the Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study (OACIS), a prospective multicentre observational registry of patients with AMI in Japan.4 19

Methods

Study population

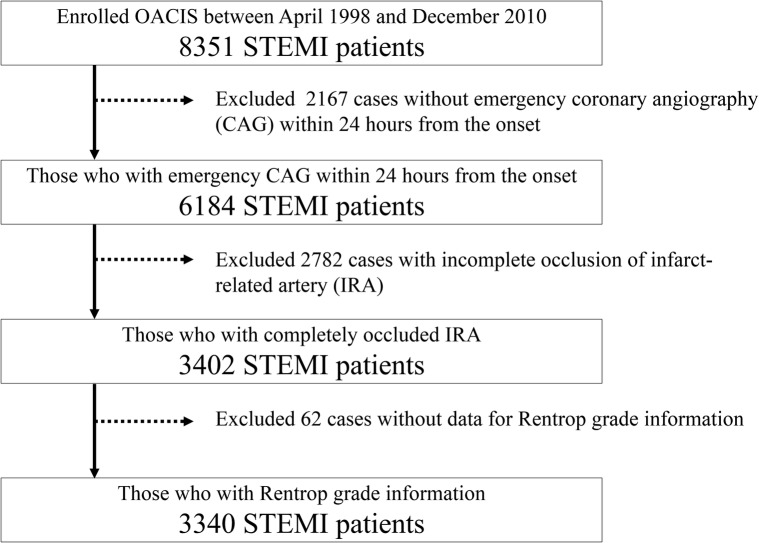

We used the OACIS database to investigate the prognostic impacts of acute phase coronary collaterals after STEMI. The OACIS is a prospective, multicentre observational study designed to collect and analyse demographic, procedural and outcome data in patients with AMI at 25 collaborating hospitals with cardiac emergency units. All the study participants were informed about data collection, blood sampling and genotyping, and provided written informed consent. The diagnosis of AMI was made on the basis of the WHO criteria, which required at least two of the following three criteria to be met: (1) clinical history of central chest pressure, pain or tightness lasting >30 min; (2) ST segment elevation >0.1 mV in at least one standard and (3) a rise in serum creatinine phosphokinase concentration to more than twice the normal laboratory value. All the collaborating hospitals were encouraged to enrol consecutive patients with AMI. We prospectively collected data by research cardiologists and trained research nurses using a specific reporting form, and the variables presented in Tables were extracted from the OACIS registry database in this study. The OACIS started in April 1998, and there were 8351 patients with STEMI as possible candidates for this study during the study period (figure 1). It is registered with the University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry (UMIN-CTR) in Japan (ID: UMIN000004575), and details are described elsewhere.4 19

Figure 1.

Patient selection flow. OACIS, Osaka Acute Coronary Insufficiency Study and STEMI, ST-elevation myocardial infarction.

This study included 3340 consecutive patients with STEMI who were registered with the OACIS between 1998 and 2010 and fulfilled the following criteria: (1) who underwent emergency coronary angiography within 24 hours after the onset, (2) complete occlusion of the IRA which means thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) flow grade 0, and (3) angiographic collateral flow was evaluated using the Rentrop collateral score (RCS) (figure 1).20 21 That is, RCS-0 indicates no visible coronary collaterals; RCS-1, coronary collaterals without IRA filling; RCS-2, coronary collaterals with partial IRA filling; and RCS-3, collaterals with complete IRA filling.21

The authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for their integrity. All authors have read and agree to the manuscript as written.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were compared by the χ2 test, and continuous variables were compared by the Kruskal-Wallis test. The impacts of coronary collaterals on in-hospital and 5-year mortality were assessed as ORs and their 95% CIs with a logistic regression analysis, and HRs and 95% CI with Cox regression analysis, respectively. To reduce the confounding effects of variations in patient backgrounds, multivariable analyses were employed where covariates were described in the footnote of each table. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate event rates, and the differences between RCS grades were assessed by the log-rank tests. To exclude the influence of stenosis of the supply artery and evaluate the impacts of coronary collaterals appropriately, the impacts of in-hospital and 5-year mortality were also evaluated in patients with single vessel disease of the main coronary arteries (left anterior descending, left circumflex and right coronary arteries) without previous MI as a subgroup analysis. Predictors of development of collaterals were assessed using univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis. Missing data were not complemented, and patients with missing data were automatically excluded in the multivariable analyses. Statistical significance was set as p<0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using R software packages V.3.2.1 for Mac (R Development Core Team).

Results

Baseline characteristics and determinants of collaterals

Patient characteristics, number of missing data and predictors of coronary collaterals are summarised in table 1, online supplementary table S1 and table 2, respectively. In general, patient backgrounds were significantly different among RCS grades in age, onset to admission hour, dyslipidaemia, previous MI, angina pectoris, culprit vessel, multivessel disease, emergency PCI, prescription rate of ACE inhibitors at discharge and angiotensin receptor blocker. In addition, median peak creatinine phosphokinase levels decreased as RCS increases (table 1).

Table 1.

Patient background

| Parameter | Overall (n=3340) | RCS-0 (n=2040) | RCS-1 (n=530) | RCS-2 (n=522) | RCS-3 (n=248) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 65 (57–73) | 66 (57–74) | 64 (55–71) | 63 (55–71) | 66 (57–74) | <0.001 |

| Male, % | 76.9 | 75.8 | 80.0 | 77.6 | 78.2 | 0.197 |

| Onset to admission, hour | 2.4 (1.1–5.5) | 2.3 (1.0–5.0) | 2.3 (1.2–5.5) | 3.0 (1.5–6.7) | 3.0 (1.3–7.4) | <0.001 |

| Coronary risk factor | ||||||

| Diabetes, % | 31.6 | 31.0 | 31.7 | 32.3 | 34.6 | 0.705 |

| Hypertension, % | 58.1 | 59.1 | 58.4 | 53.5 | 59.5 | 0.147 |

| Dyslipidaemia, % | 44.2 | 40.8 | 50.4 | 47.6 | 52.1 | <0.001 |

| Smoking, % | 65.3 | 63.7 | 68.7 | 70.4 | 59.8 | 0.003 |

| Previous MI, % | 11.0 | 10.0 | 9.2 | 14.3 | 16.3 | <0.001 |

| Angina pectoris, % | 20.7 | 17.6 | 22.8 | 25.9 | 31.1 | <0.001 |

| KILLIP classification | 0.113 | |||||

| Class 1 | 82.0 | 80.9 | 83.2 | 84.8 | 82.8 | |

| Class 2 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 10.6 | 8.0 | 8.0 | |

| Class 3 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.9 | 2.5 | |

| Class 4 | 6.2 | 7.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 6.7 | |

| Laboratory data | ||||||

| Peak CPK, IU/L | 2957 (1637–5030) | 3225 (1722–5390) | 3074 (1895–4915) | 2514 (1449–4218) | 2277 (1093–4180) | <0.001 |

| CAG findings | ||||||

| Culprit vessel | <0.001 | |||||

| Left main trunk, % | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 3.3 | |

| LAD, % | 44.0 | 42.7 | 48.3 | 45.2 | 42.7 | |

| Diagonal branch, % | 2.4 | 3.1 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 2.8 | |

| RCA, % | 41.5 | 40.1 | 43.5 | 44.8 | 41.9 | |

| LCx, % | 10.2 | 12.4 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 9.3 | |

| Graft, % | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.0 | |

| Multivessel disease, % | 35.1 | 34.3 | 29.5 | 35.6 | 53.7 | <0.001 |

| Emergency PCI, % | 96.8 | 96.4 | 98.5 | 97.5 | 95.6 | 0.042 |

| Final TIMI 3, % | 85.8 | 84.9 | 85.4 | 87.8 | 89.6 | 0.127 |

| CABG, % | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 3.7 | 0.064 |

| Medication at discharge | ||||||

| ACEI, % | 55.3 | 53.5 | 56.8 | 62.4 | 50.9 | 0.002 |

| ARB, % | 23.8 | 24.1 | 25.8 | 18.7 | 27.7 | 0.016 |

| β-Blocker, % | 48.7 | 49.0 | 50.3 | 45.0 | 51.3 | 0.271 |

| Ca-blocker, % | 16.8 | 17.9 | 15.0 | 15.3 | 15.6 | 0.297 |

| Statin, % | 41.8 | 40.9 | 42.0 | 42.0 | 47.3 | 0.334 |

| Diuretics, % | 29.0 | 29.7 | 28.8 | 26.9 | 28.6 | 0.664 |

Categorical variables are presented as percentage and continuous variables are presented as the median (25–75 percentiles).

ACEI, ACE inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CAG, coronary angiography; CPK, creatine kinase; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RCA, right coronary artery; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Table 2.

Predictors of development of collaterals

| Univariable |

Multivariable (stepwise) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | adjusted OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Age, per 10 years | 0.87 (0.82 to 0.92) | <0.001 | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.91) | <0.001 |

| Male, % | 1.18 (0.99 to 1.40) | 0.052 | – | – |

| Onset to admission, hour | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.04) | <0.001 | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05) | <0.001 |

| Coronary risk factor | ||||

| Diabetes | 1.07 (0.92 to 1.24) | 0.390 | – | – |

| Hypertension | 0.91 (0.78 to 1.05) | 0.174 | 0.87 (0.74 to 1.02) | 0.081 |

| Dyslipidaemia | 1.43 (1.24 to 1.65) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.12 to 1.53) | <0.001 |

| Smoking | 1.19 (1.03 to 1.38) | 0.020 | – | – |

| Previous MI | 1.30 (1.04 to 1.62) | 0.021 | 1.20 (0.93 to 1.54) | 0.155 |

| Angina pectoris | 1.61 (1.36 to 1.91) | <0.001 | 1.61 (1.34 to 1.94) | <0.001 |

| Culprit vessel | ||||

| LCx | 1 | reference | 1 | reference |

| LAD | 1.99 (1.53 to 2.60) | <0.001 | 2.18 (1.64 to 2.92) | <0.001 |

| RCA | 2.01 (1.55 to 2.64) | <0.001 | 2.14 (1.61 to 2.87) | <0.001 |

| Other | 1.36 (0.88 to 2.08) | 0.158 | 1.58 (0.98 to 2.52) | 0.059 |

| Multivessel disease | 1.11 (0.95 to 1.28) | 0.179 | 1.15 (0.97 to 1.35) | 0.103 |

Collaterals were divided into 2 variables (absent=RCS 0 or present=RCS 1–3).

Multivariable model was selected with stepwise method based on Akaike Information Criteria. Same results were obtained with decrease/increase and increase/decrease stepwise models.

LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; RCA, right coronary artery.

bmjopen-2016-011105supp_table.pdf (38.4KB, pdf)

Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that younger age, longer time from the onset to admission, dyslipidaemia, history of angina pectoris, left anterior descending artery, right coronary artery and presence of multivessel disease were associated with presence of collaterals in this study (table 2).

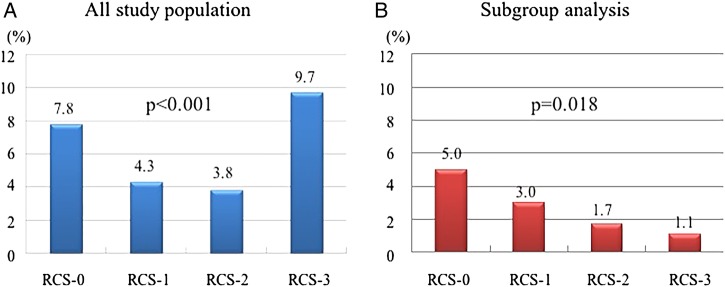

Impacts of coronary collaterals on in-hospital mortality

As shown in table 3, figure 2 and online supplementary figure S1, in-hospital mortalities were significantly lower in the RCS-1 and RCS-2 groups than in the RCS-0 group, whereas it was higher in the RCS-3 group than in the RCS-0 group. However, if we analyse the data only in patients with single vessel disease without previous MI, in-hospital mortality decreases as RCS grade increases (p=0.018). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, adjusted OR for in-hospital mortality were 0.48 (95% CI 0.22 to 0.94, p=0.046), 0.38 (0.17 to 0.76, p=0.010) and 1.35 (0.72 to 2.40, p=0.331) in the RCS-1, RCS-2 and RCS-3 groups, respectively.

Table 3.

Impact of coronary collaterals on in-hospital mortality

| All study population (n=3340) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Univariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.54 | 0.33 to 0.82 | 0.006 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.47 | 0.28 to 0.74 | 0.002 |

| Rentrop 3 | 1.27 | 0.79 to 1.95 | 0.303 |

| Multivariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.48 | 0.22 to 0.94 | 0.046 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.38 | 0.17 to 0.76 | 0.010 |

| Rentrop 3 | 1.35 | 0.72 to 2.40 | 0.331 |

| Single vessel disease without previous myocardial infarction (n=1880) | |||

| OR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Univariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.59 | 0.28 to 1.12 | 0.131 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.33 | 0.11 to 0.76 | 0.019 |

| Rentrop 3 | 0.20 | 0.03 to 1.49 | 0.118 |

| Multivariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.60 | 0.20 to 1.5 | 0.318 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.29 | 0.05 to 1.03 | 0.104 |

| Rentrop 3 | <0.01 | <0.01 to >10.0 | 0.987 |

Impact of coronary collaterals on in-hospital mortality was estimated by univariable and multivariable logistic regression analysis with Rentrop 0 serving as a reference. Age, gender, onset to admission time, coronary risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, previous myocardial infarction and angina pectoris), culprit vessel, multivessel disease and emergency percutaneous coronary intervention were used as covariates in a multivariable model.

Figure 2.

In-hospital mortality in (A) an all study population and (B) a subgroup of single vessel disease of main coronary arteries without previous myocardial infarction. RCS, Rentrop collateral score.

bmjopen-2016-011105supp_figure.pdf (351.8KB, pdf)

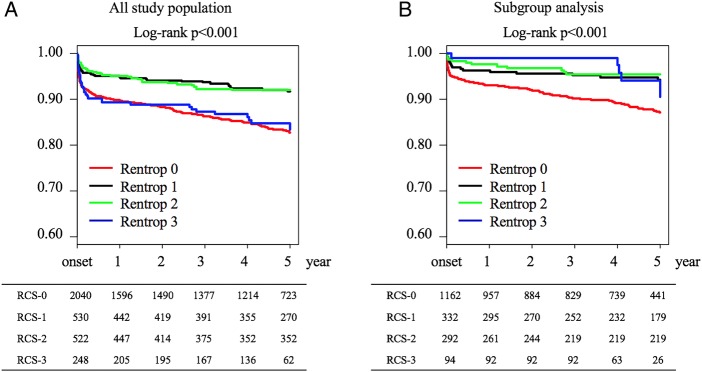

Impacts of coronary collaterals on 5-year mortality

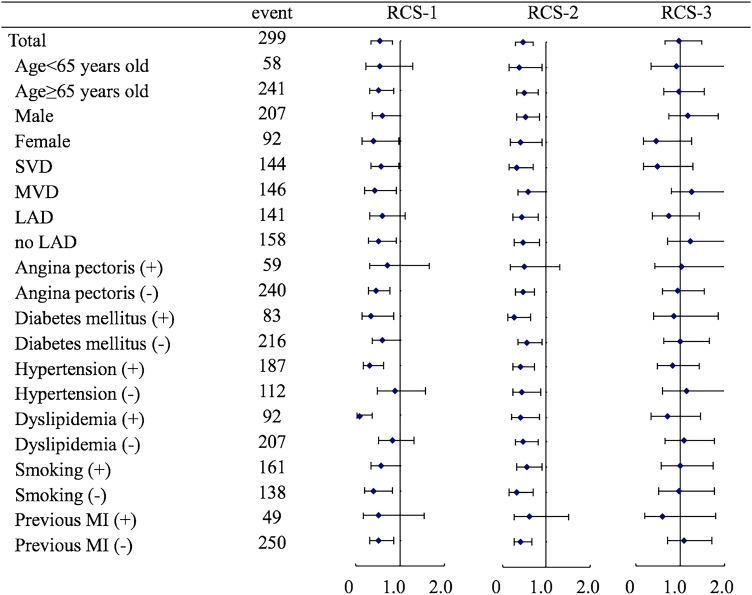

During a median follow-up duration of 1691 days (quartile 714–1824) from STEMI onset, 418 events occurred (306 in RCS-0, 39 in RCS-1, 38 in RCS-2 and 35 in RCS-3). Kaplan-Meier survival estimates are shown in figure 3. Patients with RCS-1 and RCS-2 collaterals showed significantly better 5-year survival than patients without coronary collaterals (RCS-0) or patients with RCS-3 collaterals (p<0.001). On the other hand, in a subgroup analysis, RCS-3 collaterals seemed to be associated with better survival in patients with single vessel disease without previous MI. In multivariable Cox regression analysis, adjusted HR for 5-year mortality were 0.53 (95% CI 0.34 to 0.82, p=0.004), 0.46 (0.30 to 0.70, p<0.001) and 0.98 (0.65 to 1.48, p=0.920) in the RCS-1, RCS-2 and RCS-3 groups, respectively (table 4). These trends were also suggested in all subgroups with exceptions in female patients and patients with single vessel disease where RCS-3 tended to impact favourably on 5-year mortality as compared to other subgroups (figure 4).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier survival estimates in (A) an all study population and (B) a subgroup of single vessel disease of main coronary arteries without previous myocardial infarction. Numbers at risk are summarised below the figure. RCS, Rentrop collateral score.

Table 4.

Impact of coronary collaterals on 5-year mortality

| All study population (n=3340) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Univariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.47 | 0.34 to 0.66 | <0.001 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.46 | 0.33 to 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Rentrop 3 | 0.94 | 0.66 to 1.33 | 0.714 |

| Multivariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.53 | 0.34 to 0.82 | 0.004 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.46 | 0.30 to 0.70 | <0.001 |

| Rentrop 3 | 0.98 | 0.65 to 1.48 | 0.920 |

| Single vessel disease without previous myocardial infarction (n=1880) | |||

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Univariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.45 | 0.27 to 0.74 | 0.002 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.35 | 0.20 to 0.64 | <0.001 |

| Rentrop 3 | 0.45 | 0.18 to 1.09 | 0.077 |

| Multivariable | |||

| Rentrop 0 | 1 | – | reference |

| Rentrop 1 | 0.49 | 0.26 to 0.91 | 0.025 |

| Rentrop 2 | 0.37 | 0.17 to 0.80 | 0.011 |

| Rentrop 3 | 0.56 | 0.21 to 1.55 | 0.267 |

Impact of coronary collaterals on 5-year mortality was estimated by univariable and multivariable Cox regression analysis with Rentrop 0 serving as a reference. Age, gender, coronary risk factors (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, previous myocardial infarction and angina pectoris), culprit vessel, multivessel disease, emergency percutaneous coronary intervention, ACE inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blocker, β-blocker, calcium-blocker, statin and diuretic usage were used as covariates in a multivariable model.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis for 5-year mortality adjusted HR of each Rentrop collateral score as compared with no collaterals. LAD, left anterior descending artery; MI, myocardial infarction; MVD, multivessel disease; RCA, right coronary artery; RCS, Rentrop collateral score; and SVD, single vessel disease of main coronary arteries.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the impacts of acute phase coronary collaterals on in-hospital and long-term (5-year) mortality after STEMI in the contemporary PCI era enrolling 3340 patients with an occluded IRA. This study is one of the largest studies investigating the prognostic impacts of coronary collaterals published until now.16 We revealed that RCS-1 and RCS-2 collaterals were associated with better in-hospital mortality (adjusted OR of RCS-1 is 0.48 with p=0.046, and RCS-2 is 0.38 with p=0.010) and 5-year mortality (adjusted HR of RCS-1 is 0.53 with p=0.004, and RCS-2 is 0.46 with p<0.001) as compared with RCS-0, whereas presence of RCS-3 collaterals were not associated with improved in-hospital (p=0.331) and 5-year mortality (p=0.920). Since subgroup analysis of single vessel disease without the previous MI population showed that in-hospital mortality and 5-year mortality tend to decrease as RCS grade increases (figures 2 and 3), we hypothesised that the cardioprotective impact of coronary collaterals would increase along with an increments of angiographical collateral filling (RCS-0 to RCS-3), but that worse clinical profiles in patients with RCS-3 may have masked the mortality benefit of coronary collaterals (table 1).

Our results of the acute phase cardioprotective effect and determinants of the presence of coronary collaterals were consistent with previously published data. For example median peak creatinine phosphokinase levels decreased as RCS increases (p<0.001) in this study, suggesting the acute cardioprotective effects of acute phase coronary collaterals (table 1).6 7 12 In fact, in-hospital mortality decreases as RCS grade increases in patients with single vessel disease without previous MI. This is consistent with the previously published data which suggested the association between presence of coronary collaterals and lower in-hospital mortality.11 Determinants of the presence of coronary collaterals in this study were younger age, longer time from the onset to admission, clinical history of angina pectoris, culprit vessel and presence of multivessel disease, which were also consistent with the previously published data.1 4 11 13 14

Furthermore, we believe that our data gave us new insights into the impacts of acute phase coronary collaterals in patients with STEMI. First, the presence of angiographically minimal coronary collaterals, defined as RCS-1, was even associated with better in-hospital and 5-year mortalities as compared with the absence of coronary collaterals (RCS-0). Thus, it is suggested that classifying patients with RCS-0 and RCS-1 together as a non-significant collateral group was inappropriate to assess the impacts of coronary collaterals, although many previous studies have investigated impacts of coronary collaterals thus.12 14 16 The second important finding of our study was that angiographically significant coronary collaterals (RCS-3) were not associated with better in-hospital and 5-year mortalities in the overall study population. However, since subgroup analysis of single vessel disease without previous MI revealed that RCS-3 was associated with the lowest in-hospital mortality and better 5-year mortality (figures 2B and 3B), it is conceivable that worse clinical profiles in patients with RCS-3 masked the mortality benefit of RCS-3 coronary collaterals. Thus, our observations clearly demonstrated that impacts of RCS-0, RCS-1, RCS-2 and RCS-3 should be evaluated separately to accurately assess the prognostic impacts of coronary collaterals, under the consideration of the patient's clinical background.

Recently, therapeutic promotion of coronary collateral growth is considered as a valuable treatment strategy for ischaemic heart disease and potential benefits of this therapy have been intensively investigated.22–24 The rationale of this approach is mainly based on the short-term beneficial impact of coronary collaterals.22 23 In addition to this, our study also suggested the long-term benefits of coronary collaterals in patients with STEMI, which are consistent with the recent evidence demonstrating the long-term favourable impact of coronary collaterals in stable coronary artery disease.16 25 Thus, we believe that our result may make the clinical implication such as therapeutic angiogenesis more anticipating.

Study limitations

There are several limitations that warrant mention. First, this study included only patients who were able to visit hospitals within 24 hours after STEMI onset, and who could undergo emergent coronary angiography which revealed complete occlusion of IRA (TIMI grade 0); therefore, there could be a selection bias in this study and it is not clear whether identical conclusions can be drawn for all patients with STEMI. However, we speculated that this process made it possible to assess the impact of coronary collaterals more accurately than enrolling all study population. Second, the study end point was set as all-cause mortality and one-third causes of all death events were not clearly determined. Third, collateral functionalities were not assessed with flow wires because that was not a prespecified purpose of the OACIS registry. These might lead to biased results. Thus, caution is required in interpretation of our results.

Conclusions

Presence of acute phase coronary collaterals was associated with better in-hospital and 5-year mortality after STEMI in the contemporary PCI era, if its angiographical coronary filling was minimal or moderate. However, it should be underlined that patients with angiographically significant collaterals (RCS-3) were characterised by worse baseline clinical backgrounds, and thus not necessarily associated with better survival. The benefit of acute phase coronary collaterals should be evaluated in combination with patient clinical backgrounds.

Footnotes

Collaborators: The OACIS Investigators (institutions listed in alphabetical order) Yoshiyuki Kijima; Yusuke Nakagawa; Minoru Ichikawa, Higashi-Osaka City General Hospital, Higashi-Osaka; Young-Jae Lim; Shigeo Kawano; Hideyuki Nanmori, Kawachi General Hospital, Higashi-Osaka; Hiroshi Sato, Kwasnsei Gakuin University, Nishinomiya; Takashi Shimazu; Hisakazu Fuji; Kazuhiro Aoki, Kobe Ekisaikai Hospital, Kobe; Masaaki Uematsu; Yoshio Ishida; Tetsuya Watanabe; Masashi Fujita; Masaki Awata, Kansai Rosai Hospital, Amagasaki; Michio Sugii, Meiwa Hospital, Nishinomiya; Masatake Fukunami; Takahisa Yamada; Takashi Morita, Osaka General Medical Center, Osaka; Shinji Hasegawa; Nobuyuki Ogasawara, Osaka Kosei Nenkin Hospital, Osaka; Tatsuya Sasaki; Yoshinori Yasuoka; Kiyoshi Kume, Osaka Minami Medical Center, National Hospital Organization; Kawachinagano; Hideo Kusuoka; Yukihiro Koretsune; Yoshio Yasumura; Keiji Hirooka, Osaka Medical Center, National Hospital Organization, Osaka; Masatsugu Hori (previous Chair), Osaka Prefectural Hospital Organization Osaka Medical Center for Cancer and Cardiovascular Diseases, Osaka; Kazuhisa Kodama; Yasunori Ueda; Kazunori Kashiwase; Mayu Nishio, Osaka Police Hospital, Osaka; Yoshio Yamada; Jun Tanouchi; Masami Nishino; Hiroyasu Kato; Ryu Shutta, Osaka Rosai Hospital, Sakai; Shintaro Beppu; Hiroyoshi Yamamoto, Osaka Seamens Insurance Hospital, Osaka; Issei Komuro; Shinsuke Nanto; Yasushi Matsumura; Tetsuo Minamino; Satoru Sumitsuji; Yuji Okuyama; Yasuhiko Sakata; Shungo Hikoso; Daisaku Nakatani; Masahiro Kumada; Michihiro Takeda; Shinichiro Suna, Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine, Suita; Toru Hayashi; Yasuji Doi; Ken-ichiro Okada; Noritoshi Ito, Saiseikai Senri Hospital, Suita; Kenshi Fujii; Katsuomi Iwakura; Atsushi Okamura; Motoo Date; Yoshiharu Higuchi; Koji Inoue, Sakurabashi Watanabe Hospital, Osaka; Noriyuki Akehi, Settsu Iseikai Hospital, Settsu; Eiji Hishida, Teramoto Memorial Hospital; Kawachinagano; and Shiro Hoshida; Kazuhiko Hashimura; Takayoshi Adachi; Yukinori Shinoda, Yao Municipal Hospital, Yao, Japan.

Contributors: MH, YS, DN, SS, MN, HS, TK, SN and IK were involved in the conception and design of the work. MH, YS, DN, SS, MN, HS, TK, SN and IK were involved in the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work. MH, YS and TK were involved in drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content. YS was involved in final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for University and Society Collaboration (number 19590816 and number 19390215) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Tokyo, Japan.

Competing interests: IK has received research grants and speaker’s fees from Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Astellas Pharma, DAIICHI SANKYO COMPANY, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis Pharma and Shionogi. No other authors have relationships with industry to disclose or financial associations that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol complied with the Helsinki Declaration. The study was approved by the institutional ethical committee of each participating institution.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Yoshiyuki Kijima, Yusuke Nakagawa, Minoru Ichikawa, Young-Jae Lim, Shigeo Kawano, Hideyuki Nanmori, Takashi Shimazu, Hisakazu Fuji, Kazuhiro Aoki, Masaaki Uematsu, Yoshio Ishida, Tetsuya Watanabe, Masashi Fujita, Masaki Awata, Michio Sugii, Masatake Fukunami, Takahisa Yamada, Takashi Morita, Shinji Hasegawa, Nobuyuki Ogasawara, Tatsuya Sasaki, Yoshinori Yasuoka, Kiyoshi Kume, Hideo Kusuoka, Yukihiro Koretsune, Yoshio Yasumura, Keiji Hirooka, Kazuhisa Kodama, Yasunori Ueda, Kazunori Kashiwase, Mayu Nishio, Yoshio Yamada, Jun Tanouchi, Hiroyasu Kato, Ryu Shutta, Shintaro Beppu, Hiroyoshi Yamamoto, Yasushi Matsumura, Tetsuo Minamino, Satoru Sumitsuji, Yuji Okuyama, Shungo Hikoso, Masahiro Kumada, Michihiro Takeda, Toru Hayashi, Yasuji Doi, Ken-ichiro Okada, Noritoshi Ito, Kenshi Fujii, Katsuomi Iwakura, Atsushi Okamura, Yoshiharu Higuchi, Koji Inoue, Noriyuki Akehi, Eiji Hishida, Shiro Hoshida, Kazuhiko Hashimura, Takayoshi Adachi, and Yukinori Shinoda

References

- 1.Schwartz H, Leiboff RH, Bren GB et al. . Temporal evolution of the human coronary collateral circulation after myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1984;4:1088–93. 10.1016/S0735-1097(84)80126-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakata Y, Kodama K, Adachi T et al. . Comparison of myocardial contrast echocardiography and coronary angiography for assessing the acute protective effects of collateral recruitment during occlusion of the left anterior descending coronary artery at the time of elective angioplasty. Am J Cardiol 1997;79:1329–33. 10.1016/S0002-9149(97)00134-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakata Y, Kodama K, Kitakaze M et al. . Different mechanisms of ischemic adaptation to repeated coronary occlusion in patients with and without recruitable collateral circulation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1997;30:1679–86. 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00377-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurotobi T, Sato H, Kinjo K et al. . Reduced collateral circulation to the infarct-related artery in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:28–34. 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirai T, Fujita M, Yoshida N et al. . Importance of ischemic preconditioning and collateral circulation for left ventricular functional recovery in patients with successful intracoronary thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 1993;126:827–31. 10.1016/0002-8703(93)90695-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Habib GB, Heibig J, Forman SA et al. . Influence of coronary collateral vessels on myocardial infarct size in humans. Results of phase I thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) trial. The TIMI Investigators. Circulation 1991;83:739–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christian TF, Schwartz RS, Gibbons RJ. Determinants of infarct size in reperfusion therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1992;86:81–90. 10.1161/01.CIR.86.1.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim YJ, Masuyama T, Mishima M et al. . Effect of pre-reperfusion residual flow on recovery from myocardial stunning: a myocardial contrast echocardiography study. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2000;13:18–25. 10.1016/S0894-7317(00)90038-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hirai T, Fujita M, Nakajima H et al. . Importance of collateral circulation for prevention of left ventricular aneurysm formation in acute myocardial infarction. Circulation 1989;79:791–6. 10.1161/01.CIR.79.4.791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kodama K, Kusuoka H, Sakai A et al. . Collateral channels that develop after an acute myocardial infarction prevent subsequent left ventricular dilation. J Am Coll Cardiol 1996;27:1133–9. 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00596-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pérez-Castellano N, García EJ, Abeytua M et al. . Influence of collateral circulation on in-hospital death from anterior acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31: 512–18. 10.1016/S0735-1097(97)00521-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elsman P, van 't Hof AW, de Boer MJ et al. . Zwolle Myocardial Infarction Study Group. Role of collateral circulation in the acute phase of ST segment-elevation myocardial infarction treated with primary coronary intervention. Eur Heart J 2004;25:854–8. 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Antoniucci D, Valenti R, Moschi G et al. . Relation between preintervention angiographic evidence of coronary collateral circulation and clinical and angiographic outcomes after primary angioplasty or stenting for acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:121–5. 10.1016/S0002-9149(01)02186-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorajja P, Gersh BJ, Mehran R et al. . Impact of collateral flow on myocardial reperfusion and infarct size in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J 2007;154:379–84. 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.04.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steg PG, Kerner A, Mancini GB et al. . Impact of collateral flow to the occluded infarct-related artery on clinical outcomes in patients with recent myocardial infarction: a report from the randomized occluded artery trial. Circulation 2010;121:2724–30. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.933200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meier P, Hemingway H, Lansky AJ et al. . The impact of the coronary collateral circulation on mortality: a meta-analysis. Eur Heart J 2012;33:614–21. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rechciński T, Jasińska A, Peruga JZ et al. . Presence of coronary collaterals in ST-elevation myocardial infarction patients does not affect long-term outcome. Pol Arch Med Wewn 2013;123: 29–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desch S, de Waha S, Eitel I et al. . Effect of coronary collaterals on long-term prognosis in patients undergoing primary angioplasty for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol 2010;106:605–11. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hara M, Sakata Y, Nakatani D et al. . OACIS Investigators. Comparison of 5-year survival after acute myocardial infarction using angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor versus angiotensin II receptor blocker. Am J Cardiol 2014;114:1–8. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chesebro JH, Knatterud G, Roberts R et al. . Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Trial, Phase I: a comparison between intravenous tissue plasminogen activator and intravenous streptokinase. Clinical findings through hospital discharge. Circulation 1987;76:142–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rentrop KP, Cohen M, Blanke H et al. . Changes in collateral channel filling immediately after controlled coronary artery occlusion by an angioplasty balloon in human subjects. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;5:587–92. 10.1016/S0735-1097(85)80380-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simons M, Ware JA. Therapeutic angiogenesis in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2003;2:863–71. 10.1038/nrd1226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meier P, Gloekler S, de Marchi SF et al. . Myocardial salvage through coronary collateral growth by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in chronic coronary artery disease: a controlled randomized trial. Circulation 2009;120:1355–63. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.866269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seiler C, Stoller M, Pitt B et al. . The human coronary collateral circulation: development and clinical importance. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2674–82. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meier P, Gloekler S, Zbinden R et al. . Beneficial effect of recruitable collaterals: a 10-year follow-up study in patients with stable coronary artery disease undergoing quantitative collateral measurements. Circulation 2007;116:975–83. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.703959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011105supp_table.pdf (38.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-011105supp_figure.pdf (351.8KB, pdf)