Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the association between factors influencing prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing prevalence including prostate cancer risk factors (age, ethnicity, obesity) and non-risk factors (social deprivation and comorbidity).

Setting

A cross-sectional database of 136 inner London general practices from 1 August 2009 to 31 July 2014.

Participants

Men aged ≥40 years without prostate cancer were included (n=150 481).

Primary outcome

Logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the association between PSA testing and age, ethnicity, social deprivation, body mass index (BMI) and comorbidity while adjusting for age, benign prostatic hypertrophy, prostatitis and tamsulosin or finasteride use.

Results

PSA testing prevalence was 8.2% (2013–2014), and the mean age was 54 years (SD 11). PSA testing was positively associated with age (OR 70–74 years compared to 40–44 years: 7.34 (95% CI 6.82 to 7.90)), ethnicity (black) (OR compared to white: 1.78 (95% CI 1.71 to 1.85)), increasing BMI and cardiovascular comorbidity. Testing was negatively associated with Chinese ethnicity and with increasing social deprivation.

Conclusions

PSA testing among black patients was higher compared to that among white patients, which differs from lower testing rates seen in previous studies. PSA testing was positively associated with prostate cancer risk factors and non-risk factors. Association with non-risk factors may increase the risk of unnecessary invasive diagnostic procedures.

Keywords: Prostate-specific antigen, testing prevalence, general practice, prostate cancer, ethnicity, comorbidity

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study features a large, inclusive general practice-registered population with representation from a wide range of ethnicity groups.

Use of computerised general practice coded and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) data minimised information entry errors.

This study explores the important associations between PSA testing and factors that may influence testing threshold including prostate cancer risk factors, social deprivation and comorbidity.

This study shows an increased testing rate among black men which marks a positive change in testing behaviour compared to prior studies.

Data on the reasoning for PSA testing were not available in this study.

Background

Prostate cancer is the commonest cancer in men in the UK with 41 736 new cases in 2011 and the second commonest cause of cancer death in men in the UK with 10 837 deaths in 2012.1 2 Known prostate cancer risk factors are increasing age, family history, ethnicity (black men) and obesity.2 3 Prostate cancer is rare in the under 50s, but the incidence rises rapidly with those aged 75–79 years at five times higher risk compared to 55–59 years old.2 Black men are reported to have a three times greater risk of developing prostate cancer compared to white men.4 5 In the UK, the reported age-adjusted incidence rates for African Caribbeans is 647 per 100 000 compared to 213 for Europeans and 199 for South Asians.5 A raised body mass index (BMI) has also been implicated as possible prostate cancer risk factor with some studies reporting a twofold increased risk in obese men.3 6

Currently, no prostate cancer screening programme exists in the UK and a policy for screening men aged 50–74 years every 4 years would cost an additional £800 million per annum.7 Current UK recommendations are that asymptomatic men aged over 50 who wish to have a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test may do so after careful consideration of the implications, but general practitioners (GPs) are not encouraged to proactively raise the issue of PSA testing.8 The prostate cancer risk management programme, introduced in 2002, provides patients and clinicians with balanced information on the advantages and disadvantages of PSA testing and is used to help concerned men make informed decisions regarding PSA testing.8 There still remains a high degree of variability in PSA testing, with a recent qualitative study showing that GPs have varied beliefs about the risks of prostate cancer over or under diagnosis which influences the likelihood of testing.9 Therefore, PSA testing may be influenced by other factors, such as comorbidity, that are not directly associated with prostate cancer but which may be associated with the GPs’ beliefs about the impact of invasive testing or diagnosis of prostate cancer.

PSA screening remains controversial and conflicting evidence exists as to the benefits of screening on prostate cancer mortality. While the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer showed a reduced mortality rate in patients undergoing PSA screening,10 the US Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) trial showed no statistically significant difference in mortality rates.11 However, the PLCO study had a higher contamination rate in the control group with 45% of patients having had an opportunistic PSA test in the 3 years prior to study randomisation.11 The PSA test has poor specificity in regards to prostate cancer diagnosis with up to 76% of men having a falsely raised PSA level.7 Moreover, the large number of men screened for prostate cancer have local or indolent disease and up to 84% of men diagnosed with prostate cancer survive 10 years or more;2 10 12 13 hence, the risk of unnecessary invasive diagnostic or treatment strategies with associated harmful side effects such as sexual dysfunction and incontinence is ever present.10 12 13 Conversely, prostate cancer remains the second commonest cause of cancer death in men in the UK and earlier diagnosis and treatment, especially in some patients with aggressive disease could reduce morbidity and mortality.12 Moreover, active surveillance is used as an initial management option for some patients with low risk prostate cancer reducing the negative risks of invasive treatment.12

The PSA testing rate per year in the UK is estimated to be ∼6% in men aged 45–89 years and remained unchanged between 2004 and 2011.14 15 PSA testing has previously been reported to vary with increasing age, ethnicity (decreased in black patients), geographical location, social deprivation, decision tool use and test indication.14–16 However, previous studies have relied upon self-reported data16 or have had a restrictive age inclusion criteria.14 15 Moreover, previous studies have not fully explored the influence of ethnicity in detail14 nor investigated the possible influence of comorbidity on PSA testing. The aim of this study is to investigate the association between PSA testing prevalence and factors that may influence testing including prostate cancer risk factors (age, ethnicity and obesity) and non-risk factors of social deprivation and comorbidity.

Methods

Study data and setting

Data for the study were taken from the inner east London boroughs of Newham, City and Hackney and Tower Hamlets and covered >95% of the general practice-registered population. Routine clinical data were entered on practice computers using EMIS Web software. Anonymised Read coded clinical and prescription data recorded over a 5-year period were extracted from 136 participating practices in July 2014. Data were managed according to the UK National Health Service information governance requirements and ethical approval was not required for this anonymised observational study.

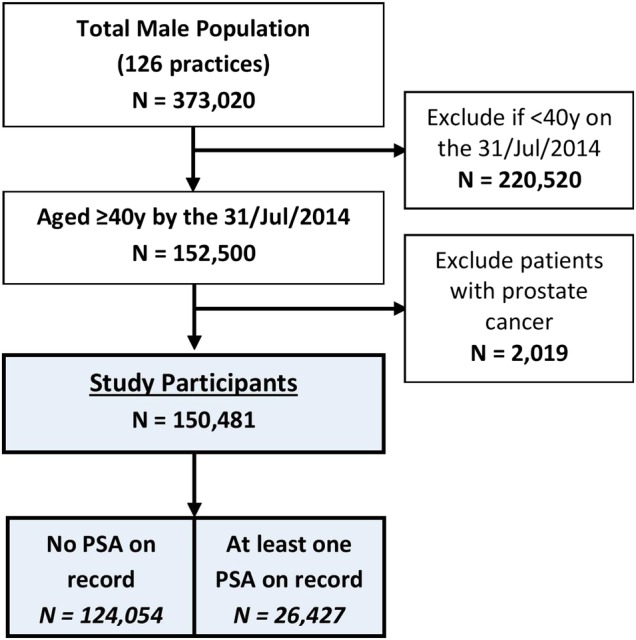

Participant selection

We included all male patients aged ≥40 years on 31 July 2014. Patients with a recorded history of prostate cancer ever were excluded as PSA testing in this setting would be for monitoring purposes and not for the detection of incident cases. Data from 150 481 patients were included in the cross-sectional study as shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

PSA testing study selection flow chart. PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

PSA measurement

The latest PSA measurement per patient recorded during the 5-year study period was used to categorise patients into tested and untested PSA groups; free and total PSA measurements were included. Patients with a PSA measurement were categorised into 0–0.99, 1–3.99, 4–9.99 and ≥10 ng/mL groups. The PSA testing prevalence was calculated as the percentage of tested study participants over the 5-year and 1-year (August 2013–2014) period. Data on the reasoning for PSA testing were not available in this study.

Study cofactors

Sociodemographics

Data on patient age, ethnicity and individual-level Townsend score (calculated using patient postcodes) as a measure of deprivation were extracted. The Townsend score is a census-based measure of deprivation and is widely used to assess deprivation in the UK.17 Patients were categorised into 5-year age groups and were placed into approximate deprivation quintiles based on the relative Townsend scores; 272 (0.18%) patients did not have a Townsend score on record. Ethnicity was self-reported by patients during practice visits and recorded using 2001 UK census ethnicity codes. For the purposes of this study, ethnic groups were grouped into white (British, Irish, other white), black (African, Caribbean, other black), mixed black, South Asian (Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, other Asian), Chinese, mixed Asian, other mixed and other ethnicity. Those without a recorded ethnicity were categorised as ‘not defined’ and included in the analysis. There were 13 149 patients (8.7%) without a recorded ethnicity.

Body mass index

Data on the BMI (kg/m2) were extracted for the study period with the latest BMI used to categorise patients. Patients were categorised into normal weight (18.5–24.9), underweight (<18.5), overweight (25–29.9), obese class I (30–34.9), class II (35–39.9) and class III (≥40) groups. There were 11 462 (7.6%) patients without a recorded BMI.

Comorbidity

Comorbidities included in this study were placed into four disease clusters.

The cardiovascular cluster, which included ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, heart failure and atrial fibrillation grouped together as cardiovascular disease (CVD). Hypertension (HTN), type I and II diabetes mellitus (DM), chronic kidney disease (stages 3–5) and stroke/transient ischaemic attack were also individually included in the cardiovascular cluster.

The respiratory cluster, which included asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

The mental health cluster, which included dementia and serious mental illness (SMI). SMI group included schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, mania and psychosis.

Other cancer (excluding prostate cancer).

The selected comorbidities were chosen as they were all Quality Outcome Framework (HSCIC, 2014)-related domains, hence were well recorded and represented prevalent, clinical conditions that GPs may take into consideration when deciding upon the appropriateness of PSA testing. Presence of the select comorbidities was identified from the data using unique clinical codes (Read codes) used in UK general practice data coding.

Adjusted covariates

Presence of benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) or prostatitis was defined as a diagnosis existing at any point throughout the patient records. Data on tamsulosin or finasteride use, used for the treatment of symptomatic BPH, were also extracted and were defined as the issue of a prescription at any point during the 5-year study period. BPH and prostatitis symptoms and presentation overlap with those of prostate cancer, which may prompt PSA testing, hence their inclusion. Similarly, finasteride and tamsulosin, used for the treatment of BPH, influence PSA levels or disease symptomology, hence may influence the decision to undertake PSA testing.

Statistical methods

Normally distributed continuous variables were analysed as means and SDs, and dichotomous variables were analysed as counts and percentages. Parametric tests for significant differences were determined using unpaired t–test or χ2 test as appropriate.

Logistic regression analyses, with 95% CIs, were used to assess the association between the odds of PSA testing and age, ethnicity, deprivation quintile, BMI and comorbidity (the comorbidity cluster and individual comorbidities were tested). The 40–44 years, white, least deprived quintile, normal weight, absence of the comorbidity cluster or individual comorbidity acted as the reference for the aforementioned cofactors. Two adjusted models were derived per cofactor analyses: (1) an age-adjusted model and (2) an age-adjusted and covariate-adjusted (BPH, prostatitis, tamsulosin or finasteride use) model. All statistical analyses were carried out on SPSS, V.20.0 (IBM, USA).

Results

Characteristics of PSA tested and untested patients

The prevalence of PSA testing over the previous 5 years was 17.6% (n=26 427, practice IQR 12.2–20.3%) for male patients aged ≥40 years. The 1 year PSA testing prevalence (1 August 2013–31 July 2014) was 8.2% (n=11 065, practice IQR 4.8–9.7%). The mean age of included patients was 53.6 years (SD 11.4). Over 66% were classified as overweight or obese and a significant proportion had HTN (25.5%), DM (15.6%) or CVD (9.1%). There were significant differences in the age, ethnicity, social deprivation, BMI, comorbidity and covariate status between PSA tested and untested patients (p<0.001, table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of PSA tested and untested patients

| Baseline characteristics | All (n=150 481) | PSA untested (n=124 054) | PSA tested (n=26 427) | p Value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate cancer risk factors | ||||

| Age, mean (SD) | 53.6 (11.4) | 52.1 (10.7) | 60.8 (11.9) | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity, % (N) | ||||

| White | 40.9 (61 621) | 41.0 (50 897) | 40.6 (10 724) | <0.001 |

| Black | 17.2 (25 956) | 16.0 (19 835) | 23.2 (6121) | |

| South Asian† | 26.1 (39 341) | 26.5 (32 858) | 24.5 (6483) | |

| Chinese | 0.9 (1363) | 1.0 (1200) | 0.6 (163) | |

| Mixed black | 1.5 (2299) | 1.3 (1647) | 2.5 (652) | |

| Mixed Asian† | 0.2 (235) | 0.2 (195) | 0.2 (40) | |

| Other mixed | 0.4 (608) | 0.4 (535) | 0.3 (73) | |

| Other ethnicity | 3.9 (5909) | 3.9 (4857) | 4.0 (1052) | |

| Not specified | 8.7 (13 149) | 9.7 (12 030) | 4.2 (1119) | |

| BMI class‡, % (N) | ||||

| Normal weight | 31.6 (47 619) | 35.4 (40 140) | 29.1 (7479) | <0.001 |

| Underweight | 1.0 (1558) | 1.2 (1321) | 0.9 (237) | |

| Overweight | 39.1 (58 787) | 42.0 (47 614) | 43.5 (11 173) | |

| Obese class I | 15.3 (22 985) | 15.9 (17 993) | 19.4 (4992) | |

| Obese class II | 4.0 (6026) | 4.1 (4653) | 5.3 (1373) | |

| Obese class III | 1.4 (2044) | 1.4 (1586) | 1.8 (458) | |

| Non-risk factors | ||||

| Deprivation§, % (N) | ||||

| Least deprived | 21.8 (32 780) | 21.5 (26 646) | 23.2 (6134) | <0.001 |

| Q2 | 16.6 (25 022) | 16.6 (20 519) | 17.1 (4503) | |

| Q3 | 17.1 (25 802) | 17.2 (21 253) | 17.2 (4549) | |

| Q4 | 19.0 (28 637) | 19.1 (23 654) | 18.9 (4983) | |

| Most deprived | 25.2 (37 968) | 25.6 (31 748) | 23.6 (6220) | |

| Comorbidity, % (N) | ||||

| HTN | 25.5 (38 399) | 21.6 (26 814) | 43.8 (11 585) | <0.001 |

| CVD | 9.1 (13 635) | 7.4 (9220) | 16.7 (4415) | <0.001 |

| DM | 15.6 (23 421) | 13.8 (17 100) | 23.9 (6321) | <0.001 |

| CKD stages 3–5 | 4.1 (6098) | 3.2 (3918) | 8.2 (2180) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 2.4 (3583) | 2.0 (2458) | 4.3 (1125) | <0.001 |

| Asthma | 8.5 (12 792) | 8.1 (10 012) | 10.5 (2780) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 3.5 (5206) | 2.9 (3550) | 6.3 (1656) | <0.001 |

| Dementia | 0.6 (920) | 0.5 (600) | 1.2 (320) | <0.001 |

| SMI | 2.5 (3699) | 2.5 (3094) | 2.3 (605) | 0.510 |

| Cancer¶ | 1.8 (2719) | 1.5 (1898) | 3.1 (821) | <0.001 |

| Covariates | ||||

| BPH, % (N) | 3.5 (5271) | 1.4 (1787) | 13.2 (3484) | <0.001 |

| Prostatitis, % (N) | 1.6 (2405) | 0.9 (1113) | 4.9 (1292) | <0.001 |

| Tamsulosin use, % (N) | 7.2 (10 825) | 3.2 (4021) | 25.7 (6804) | <0.001 |

| Finasteride use, % (N) | 2.4 (3610) | 1.1 (1419) | 8.3 (2191) | <0.001 |

Bold typeface indicates significance at p≤0.05.

*χ2 between tested and untested groups.

†Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi or other Asian.

‡11 462 BMI values missing.

§Townsend score quintiles (272 scores missing).

¶Excludes benign or malignant prostate cancer.

BPH, benign prostate hypertrophy; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SMI, significant mental illness.

PSA testing prevalence, level and age

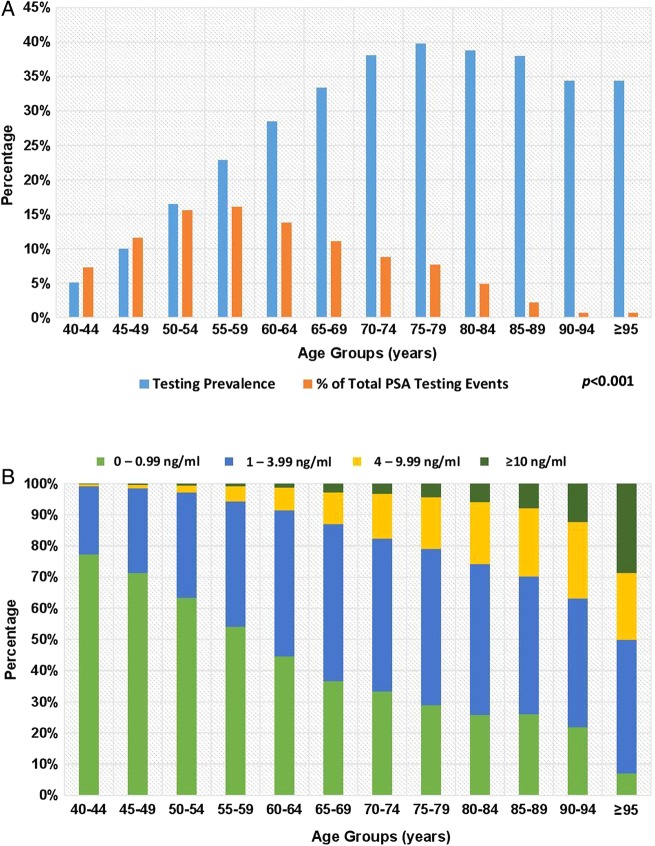

As shown in figure 2A, the PSA testing prevalence increased significantly with age from 5.1% at age 40–44 years to 39.7% at age 70–74 years (p<0.001). However, the greatest proportion of PSA tests performed occurred in patients aged 55–59 years (16.1%) with just 7% of all PSA tests performed in patients aged 70–74 years.

Figure 2.

(A, B) PSA testing prevalence, level and age. PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

The PSA level rose significantly with age, with 0.8% of patients aged 40–44 years having a PSA level of 4 ng/mL or greater, rising to 17.5% by age 70–74 years and 36.9% by age 90–94 years (figure 2B). The median (IQR) PSA values were 0.68 ng/mL (0.45–1.00) for 40–49 years, 0.81 ng/mL (0.50–1.40) for 50–59 years, 1.20 ng/mL (0.65–2.30) for 60–69 years, 1.63 ng/mL (0.80–3.30) for 70–79 years, 2.08 ng/mL (0.93–4.28) for 80–89 years and 2.90 ng/mL (1.25–6.31) for ≥90 years.

Association between PSA testing and age, ethnicity, social deprivation, BMI and comorbidity

PSA testing was positively associated with age. The adjusted OR of PSA testing in the 70–74 years age group was 7.34 (95% CI 6.82 to 7.90), compared to those baseline 40–44 years age group (table 2). Moreover, the odds of PSA testing increased in each age cohort peaking at 70–74 years and decreasing thereafter up to the ≥95 years age group.

Table 2.

Association between PSA testing and age, ethnicity, social deprivation, BMI and comorbidity

| Cofactor | Description | PSA study group (N=150 481) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Age-adjusted OR (95% CI)* | Age-adjusted and covariate-adjusted OR (95% CI)† | ||

| Prostate cancer risk factors | ||||

| Age | 40–44 years (n=37 668) | 1.00 (Reference) | NA | 1.00 (Reference) |

| 45–49 years (n=30 792) | 2.04 (1.92 to 2.17) | NA | 2.00 (1.88 to 2.12) | |

| 50–54 years (n=24 982) | 3.66 (3.45 to 3.87) | NA | 3.44 (3.25 to 3.65) | |

| 55–59 years (n=18 658) | 5.47 (5.17 to 5.79) | NA | 4.81 (4.54 to 5.10) | |

| 60–64 years (n=12 814) | 7.37 (6.94 to 7.82) | NA | 5.91 (5.56 to 6.29) | |

| 65–69 years (n=8839) | 9.21 (8.64 to 9.81) | NA | 6.71 (6.28 to 7.17) | |

| 70–74 years (n=6105) | 11.31 (10.55 to 12.11) | NA | 7.34 (6.82 to 7.90) | |

| 75–79 years (n=5152) | 12.14 (11.29 to 13.05) | NA | 6.86 (6.35 to 7.42) | |

| 80–84 years (n=3320) | 11.64 (10.71 to 12.65) | NA | 6.02 (5.49 to 6.60) | |

| 85–89 years (n=1527) | 11.24 (10.04 to 12.59) | NA | 5.41 (4.77 to 6.14) | |

| 90–94 years (n=522) | 9.63 (7.99 to 11.61) | NA | 4.35 (3.54 to 5.35) | |

| ≥95 years (n=102) | 6.98 (4.51 to 10.81) | NA | 3.25 (2.02 to 5.24) | |

| Ethnicity | White (n=61 621) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Black (n=25 956) | 1.47 (1.41 to 1.52) | 1.74 (1.68 to 1.81) | 1.78 (1.71 to 1.85) | |

| South Asian‡ (n=39 341) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.97) | 1.13 (1.09 to 1.17) | 1.08 (1.04 to 1.12) | |

| Chinese (n=1363) | 0.65 (0.55 to 0.76) | 0.66 (0.56 to 0.78) | 0.67 (0.56 to 0.80) | |

| Mixed black (n=2299) | 1.88 (1.71 to 2.06) | 2.23 (2.02 to 2.46) | 2.25 (2.03 to 2.50) | |

| Mixed Asian‡ (n=235) | 0.97 (0.69 to 1.37) | 1.23 (0.86 to 1.76) | 1.21 (0.83 to 1.76) | |

| Other mixed (n=608) | 0.65 (0.51 to 0.83) | 1.03 (0.80 to 1.32) | 1.00 (0.77 to 1.30) | |

| Other ethnicity (n=5909) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.10) | 1.19 (1.11 to 1.29) | 1.10 (1.02 to 1.19) | |

| Not defined (n=13 149) | 0.44 (0.41 to 0.48) | 0.57 (0.53 to 0.61) | 0.60 (0.56 to 0.65) | |

| BMI§ | Normal weight (n=47 619) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Underweight (n=1558) | 0.96 (0.84 to 1.11) | 0.79 (0.68 to 0.92) | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.95) | |

| Overweight (n=58 787) | 1.26 (1.22 to 1.30) | 1.19 (1.15 to 1.23) | 1.18 (1.14 to 1.22) | |

| Obese class I (n=22 985) | 1.49 (1.43 to 1.55) | 1.31 (1.26 to 1.37) | 1.29 (1.24 to 1.35) | |

| Obese class II (n=6026) | 1.58 (1.48 to 1.69) | 1.34 (1.26 to 1.44) | 1.31 (1.22 to 1.41) | |

| Obese class III (n=2044) | 1.55 (1.39 to 1.73) | 1.36 (1.22 to 1.52) | 1.38 (1.23 to 1.55) | |

| Non-risk factors | ||||

| Deprivation quintiles**,¶ | Least deprived (n=32 780) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) | 1.00 (Reference) |

| Q2 (n=25 022) | 0.95 (0.91 to 1.00 | 0.97 (0.92 to 1.01) | 0.96 (0.92 to 1.01) | |

| Q3 (n=25 802) | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.97) | 0.95 (0.90 to 0.99) | 0.94 (0.90 to 0.99) | |

| Q4 (n=28 637) | 0.92 (0.88 to 0.95) | 0.90 (0.86 to 0.94) | 0.89 (0.85 to 0.93) | |

| Most deprived (n=37 968) | 0.85 (0.82 to 0.89) | 0.85 (0.82 to 0.89) | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.87) | |

| Comorbidity†† | Cardiovascular cluster (n=53 120) | 2.92 (2.87 to 3.03) | 1.60 (1.55 to 1.65) | 1.51 (1.46 to 1.56) |

| HTN (n=38 399) | 2.83 (2.75 to 2.91) | 1.53 (1.50 to 1.60) | 1.49 (1.44 to 1.54) | |

| CVD‡‡ (n=13 635) | 2.50 (2.40 to 2.60) | 1.19 (1.14 to 1.24) | 1.07 (1.02 to 1.12) | |

| DM (n=23 421) | 1.97 (1.90 to 2.03) | 1.22 (1.18 to 1.27) | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.21) | |

| CKD stage 3–5 (n=6098) | 2.76 (2.61 to 2.91) | 1.23 (1.16 to 1.31) | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.21) | |

| Stroke (n=3583) | 2.20 (2.05 to 2.36) | 1.03 (0.96 to 1.11) | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.06) | |

| Respiratory cluster (n=16 616) | 1.55 (1.28 to 1.40) | 1.18 (1.13 to 1.22) | 1.08 (1.03 to 1.13) | |

| Asthma (n=12 792) | 1.34 (1.28 to 1.40) | 1.25 (1.19 to 1.31) | 1.15 (1.10 to 1.21) | |

| COPD (n=5206) | 2.27 (2.14 to 2.41) | 1.06 (1.00 to 1.13) | 0.95 (0.89 to 1.02) | |

| Mental health cluster (n=4572) | 1.18 (1.09 to 1.27) | 0.94 (0.87 to 1.02) | 0.91 (0.84 to 0.99) | |

| Dementia (n=920) | 2.52 (2.20 to 2.89) | 0.92 (0.80 to 1.05) | 0.82 (0.70 to 0.96) | |

| SMI (n=3699) | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | |

| Other cancer§§ (n=2719) | 2.06 (1.90 to 2.24) | 1.13 (1.03 to 1.23) | 1.02 (0.93 to 1.12) | |

Bold typeface indicates significance at p<0.05.

*Age adjusted in age groups 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79, 80–84, 85–89, 90–94 and ≥95.

†Adjusted for age, BPH, prostatitis, tamsulosin or finasteride use.

‡Indian, Pakistani Bangladeshi or other Asian.

§11 462 BMI values missing.

¶272 Townsend scores missing.

**Quintiles based on Townsend Scores −5 to +10.

††Absence of comorbidity (individual or cluster) acts as reference group.

‡‡Includes IHD, PAD, AF and HF.

§§Excludes benign or malignant prostate cancer.

AF, atrial fibrillation; BPH, benign prostate hypertrophy; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; HF, heart failure; HTN, hypertension; IHD, ischaemic heart disease; PSA, prostate-specific antigen; SMI, significant mental illness.

Compared to white patients, black (adjusted OR 1.78 (95% CI 1.71 to 1.85)), mixed black and to lesser degree South Asian patients were significantly more likely to undergo PSA testing. This remained true for black and mixed black patients after further adjustment for included comorbidity clusters (data not shown), but the OR for South Asians become non-significant. Conversely, Chinese patients were significantly less likely to undergo PSA testing than white patients (table 2); there was minimal change in the OR after adjusting for included comorbidities (data not shown).

Increasing social deprivation was inversely associated with the odds of PSA testing (table 2).

Compared to patients of a normal BMI, obese patients were significantly more likely to undergo PSA testing (adjusted OR 1.29 (95% CI 1.24 to 1.35)). The likelihood of PSA testing increased with each BMI class above normal weight and decreased in underweight patients (table 2).

PSA testing was significantly associated with cardiovascular comorbidity, especially with HTN. Dementia but not SMI showed an inverse association with PSA testing. There was a weak association between PSA testing and respiratory disease with no significant difference in testing in patients with a diagnosis of other cancer (table 2).

Discussion

Summary

PSA testing prevalence was positively associated with increasing age, black, mixed black and South Asian ethnicity, increasing BMI and cardiovascular comorbidity. In contrast, PSA testing was inversely associated with Chinese ethnicity and greater social deprivation.

Prevalence of PSA testing

Based on our findings, the 1-year PSA testing prevalence in inner east London (8.2%) was higher than the 6.2% reported in previous studies by Melia et al14 and Williams et al.15 However, both studies excluded older patients with an inclusion age criteria of 45–84 and 45–89 years, respectively.14 15 Additionally, Williams et al15 reported higher PSA testing rates (7.1–8.9%) in the southern UK general practices. Differences are likely to be multifactorial including north and south social deprivation differences.15 Based on reported 1 year PSA testing rates in the UK, there has been a modest 2% rise in testing rates from 6.2%14 15 to the current rate of 8.2% in our study.

We observed a significant degree of variability in the PSA testing rate between practices, which is similar to previous findings, IQR 3.6–8.4% (Williams et al15), and may be a reflection of differences in practice organisation, GP attitudes to testing or patient demographics. Yearly PSA testing rates also vary greatly between developed countries with greater testing in some EU countries (Germany 35%),16 New Zealand (22%)18 and a greater degree of testing in the USA (57%).19 Hjertholm et al13 found no difference in prostate cancer-specific mortality between Danish practices with the highest and lowest relative levels of PSA testing, but there was a significant increase in prostate cancer diagnoses (mainly local disease), prostate biopsy and prostatectomy.

PSA testing, level and age

Similar to the findings of others, PSA testing rates increase with age,14–16 18–20 and peak testing prevalence is among the patients aged 70–80 years old.14 15 18–20 A third of those aged ≥70 years have PSA levels ≥4 ng/mL,14 15 21 which was consistent with our own findings.

PSA testing and ethnicity

In contrast to our study, Melia et al14 reported a decrease in PSA testing with increasing proportions of black and South Asian men. This finding was echoed by Gorday et al22 who found a decreased rate of PSA testing among black Canadian men. Further US studies have found little difference in PSA uptake between black and white patients.23–25 This is despite the increased incidence and mortality of prostate cancer among black men.4 5 26 27 To the best of our knowledge, our study results are first to show higher rates of PSA testing among black men, which marks a positive change in testing behaviour potentially reflecting the increased underlying risk of prostate cancer and possibly driven by increased awareness of risk by patients and GPs. However, given that black men are at up to three times greater risk of developing prostate cancer, the raised ORs for testing found in our study do not sufficiently reflect the increased risk of prostate cancer in this group. The decreased PSA testing among Chinese men may reflect the reduced incidence and mortality risk of prostate cancer in the native Chinese population.28

PSA testing and social deprivation

The inverse relationship between socioeconomic status and PSA testing observed in this study has been reported in the UK14 15 and internationally.16 25 Purported reasons for this relationship are reduced access to health services in deprived areas and increased health awareness with greater patient-driven testing among less deprived patients.15 16 Prostate cancer mortality has also been found to be higher in more deprived populations.27 Although we used internal quartiles of deprivation and the studied London boroughs had high levels of deprivation, PSA testing should still be a patient-driven and clinician-driven process and efforts should to be made to reduce any socioeconomic disparities in testing.

PSA testing and BMI

Similar to our study findings, US studies by Fontaine et al29 and Fowke et al30 found a trend of increasing PSA testing with increasing BMI. A raised BMI is a proposed risk factor for prostate cancer, especially for advanced tumours.6 In this study, the increased PSA testing in obese patients more likely represents opportunistic testing in such patients who are more likely to have CVD associated with increased healthcare access.30

PSA testing and comorbidity

Fowke et al30 found an increased rate of PSA testing in patients with comorbidity, particularly CVD (HTN, DM and high cholesterol) but no association with coronary heart disease or respiratory disease. Minor dissimilarities between the findings are likely to be the result of methodological differences such as their inclusion of a younger age range and adjustment for differing cofactors (Fowke et al30).

A possible mechanism for the observed relationship between some comorbidities and PSA testing is that increased consultation rates and routine blood test monitoring for comorbidity could increase the opportunity to add PSA testing to existing monitoring tests. This hypothesis was also suggested by Fowke et al30 who first reported for the positive association between CVD and PSA testing among obese men. Lack of association between PSA testing rates and other comorbidities may be related to lack of routine blood test monitoring in these comorbidities although this is unlikely to be the sole explanation since increased PSA screening rates were also seen in patients with asthma, a comorbidity not associated with blood test monitoring.

Strengths and limitations

The results of this study are reflective of current clinical practice as it features a large GP-registered population with an inclusive criteria featuring a broad age range with representation from various ethnicity groups, conducted over a 5-year period. Our study used routinely collected PSA testing data directly linked to computerised general practice systems largely avoiding data entry errors and reporting bias that occur with self-reported data. The use of a retrospective study design meant that PSA testing behaviour at the general practice level was not altered by the knowledge of an ongoing study.

Study limitations were that data on the PSA testing intent and whether patients were symptomatic or asymptomatic were not available. Similarly, we did not have data on whether PSA testing was initiated by the patient or GP. There are other drugs used on occasion for patients with prostatic symptoms or that may influence PSA levels that were not adjusted for in this study.

Conclusions

Based on our data from inner east London, 1-year PSA testing prevalence showed a modest increase from previous studies but was relatively low compared to other EU countries and the USA. Patients at higher risk of prostate cancer (older patients, black men and obese patients) had higher PSA testing rates; those at lower risk (patients of Chinese ethnicity) had lower testing rates. Independent of prostate cancer risk factors, patients living in more socially deprived areas had lower PSA testing rates and those with cardiovascular comorbidities had higher testing rates likely due to opportunistic testing. This study indicates that PSA testing may be influenced by prostate cancer risk factors and non-risk factors. In light of the current lack of evidence demonstrating a benefit in outcomes in testing asymptomatic men, positive associations with non-prostate risk factors may potentially increase the risk of invasive diagnostic procedures. Future studies should explore the intention for PSA testing in general practice, especially in relation to ethnicity, comorbidity and social deprivation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients and general practitioners for all their contributions that have made this study possible.

Footnotes

Contributors: PN, MVH, MA, AD and SC conceived and refined the initial study design. PN and AD performed the background review. PN, MVH, RM and SH collated the study data and PN carried out the primary data analysis. PN, MVH, MA, RM, SH, AD and SC were involved in the data interpretation and refined the primary study design and data analysis. PN drafted the initial manuscript. PN, MVH, MA, RM, SH, AD and SC refined the draft manuscript and approved the final submitted article.

Funding: This study was funded by the Guy's and St Thomas' Hospital Charity (Fund 201).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.NICE. Prostate cancer: diagnosis and treatment. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CRUK. Cancer Research UK. 2014. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancer-info/cancerstats/types/prostate/

- 3.Bostwick DG, Burke HB, Djakiew D et al. . Human prostate cancer risk factors. Cancer 2004;101(Suppl 10):2371–490. 10.1002/cncr.20408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chinegwundoh F, Enver M, Lee A et al. . Risk and presenting features of prostate cancer amongst African-Caribbean, South Asian and European men in North-east London. BJU Int 2006;98:1216–20. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06503.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kheirandish P, Chinegwundoh F. Ethnic differences in prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 2011;105:481–5. 10.1038/bjc.2011.273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.MacInnis RJ, English DR. Body size and composition and prostate cancer risk: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:989–1003. 10.1007/s10552-006-0049-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackie A. Screening for prostate cancer: review against programme appraisal criteria for the UK National Screening Committee (UKNSC). UK National Screening Committee, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burford DC, Kirby M, Austoker J. Prostate cancer risk management programme: information for primary care; PSA testing in asymptomatic men. NHS Cancer Screening Programme, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pickles K, Carter SM, Rychetnik L. Doctors’ approaches to PSA testing and overdiagnosis in primary healthcare: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006367 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schröder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ et al. . Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet 2014;384:2027–35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andriole GL, Crawford ED, Grubb RL III et al. . Prostate cancer screening in the randomized Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial: mortality results after 13 years of follow-up. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012;104:125–32. 10.1093/jnci/djr500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cooperberg MR, Lubeck DP, Meng MV et al. . The changing face of low-risk prostate cancer: trends in clinical presentation and primary management. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:2141–9. 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hjertholm P, Fenger-Grøn M, Vestergaard M et al. . Variation in general practice prostate-specific antigen testing and prostate cancer outcomes: an ecological study. Int J Cancer 2015;136:435–42. 10.1002/ijc.29008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Melia J, Moss S, Johns L. Rates of prostate-specific antigen testing in general practice in England and Wales in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients: a cross-sectional study. BJU Int 2004;94:51–6. 10.1111/j.1464-4096.2004.04832.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams N, Hughes LJ, Turner EL et al. . Prostate-specific antigen testing rates remain low in UK general practice: a cross-sectional study in six English cities. BJU Int 2011;108:1402–8. 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2011.10163.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burns R, Walsh B, O'Neill S et al. . An examination of variations in the uptake of prostate cancer screening within and between the countries of the EU-27. Health Policy 2012;108:268–76. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.08.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A. Health and deprivation. Inequality and the North. London: Croom-Helm, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zuzana O, Ross L, Fraser H et al. . Screening for prostate cancer in New Zealand general practice. J Med Screen 2013;20:49–51. 10.1177/0969141313485729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sirovich BE, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Screening men for prostate and colorectal cancer in the United States: does practice reflect the evidence? JAMA 2003;289:1414–20. 10.1001/jama.289.11.1414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.D'Ambrosio GG, Campo S, Cancian M et al. . Opportunistic prostate-specific antigen screening in Italy: 6 years of monitoring from the Italian general practice database. Eur J Cancer Prev 2010;19:413–16. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32833d944b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Melia J, Moss S. Survey of the rate of PSA testing in general practice. Br J Cancer 2001;85:656–7. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorday W, Sadrzadeh H, de Koning L et al. . Association of sociodemographic factors and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing. Clin Biochem 2014;47:164–9. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mariotto AB, Etzioni R, Krapcho M et al. . Reconstructing PSA testing patterns between black and White men in the US from Medicare claims and the National Health Interview Survey. Cancer 2007;109:1877–86. 10.1002/cncr.22607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu Y, Sorkin JD, Dwyer D et al. . Predictors of repeated PSA testing among black and White men from the Maryland Cancer Survey, 2006. Prev Chronic Dis 2011;8:A114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scales CD, Antonelli J, Curtis LH et al. . Prostate-specific antigen screening among young men in the United States. Cancer 2008;113:1315–23. 10.1002/cncr.23667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taksler GB, Keating NL, Cutler DM. Explaining racial differences in prostate cancer mortality. Cancer 2012;118:4280–9. 10.1002/cncr.27379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ward E, Jemal A, Cokkinides V et al. . Cancer disparities by race/ethnicity and socioeconomic status. CA Cancer J Clin 2004;54: 78–93. 10.3322/canjclin.54.2.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kazuto I. Prostate cancer in Asian men. Nat Rev Urol 2014;11:192–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fontaine KR, Heo M, Allison DB. Obesity and prostate cancer screening in the USA. Public Health 2005;119:694–8. 10.1016/j.puhe.2004.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fowke JH, Signorello LB, Undwerwood W III et al. . Obesity and prostate cancer screening among African-American and Caucasian men. Prostate 2006;66:1371–80. 10.1002/pros.20377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]