Abstract

Purpose

The aim of the Medicine use and Alzheimer's disease (MEDALZ) study is to investigate the changes in medication and healthcare service use among persons with Alzheimer's disease (AD) and to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of medications in this group. This is important, because the number of persons with AD is rapidly growing and even though they are a particularly vulnerable patient group, the number of representative, large-scale studies with adequate follow-up time is limited.

Participants

MEDALZ contains all residents of Finland who received a clinically verified diagnosis of AD between 2005 and 2011 and were community-dwelling at the time of diagnosis (N=70 719). The diagnosis is based on the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (NINCS-ADRDA) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for Alzheimer's disease. The cohort contains socioeconomic data (education, occupational status and taxable income, 1972–2012) and causes of death (2005–2012), data from the prescription register (1995–2012), the special reimbursement register (1972–2012) and the hospital discharge register (1972–2012). Future updates are planned.

The average age was 80.1 years (range 34.5–104.6 years). The majority of cohort (65.2%) was women. Currently, the average length of follow-up after AD diagnosis is 3.1 years and altogether 26 045 (36.8%) persons have died during the follow-up.

Findings

Altogether 53% of the cohort had used psychotropic drugs within 1 year after AD diagnoses. The initiation rate of for example, benzodiazepines and related drugs and antidepressants began to increase already before AD diagnosis.

Future plans

We are currently assessing if these, and other commonly used medications are related to adverse events such as death, hip fractures, head injuries and pneumonia.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, medication, healthcare service use, comorbidities

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Medicine use and Alzheimer's disease (MEDALZ) contains all residents of Finland who received a clinically verified diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) in between 2005 and 2012 and were community-dwelling at the time of diagnosis (N=70 719).

Studies like MEDALZ provide means for assessing the safety and effectiveness of interventions in population groups that are under-represented in randomised controlled trials.

The main limitation of all register-based studies, not specific to ours, is the lack of information on certain confounders, such as body composition, smoking or alcohol use. These can be partially captured by using medical histories, or by the within-subject study design that controls for fixed, unmeasured confounding.

Introduction

Global life expectancy has increased from 65.3 years to 71.5 years between 1990 and 2013.1 However, the simultaneous increase in healthy life expectancy was smaller.1 While the years of life lost, for example, due tocommunicable, maternal, neonatal and nutritional disorders have rapidly decreased,1 a steep increase in years of life lost or lived with disability due to chronic diseases has occurred.1–3

Dementia, with Alzheimer's disease (AD) being the most common form, is the most important determinant of healthcare service use and health-related quality of life.1–3 In 2010, 35.6 million people were estimated to have dementia, and the number is predicted to double by 2030 and more than triple by 2050.3 This will have dire consequences on the healthcare systems as there is no curative treatment for dementia. Importantly, changes in population structure are not only occurring in industrialised countries, but also in those countries that are under transition phase. Thus, large population-based research efforts on ways to delay the institutionalisation or deterioration of health status are urgently needed.

One specific problem in this group is the lack of effectiveness evidence on the symptomatic treatments. Many randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have assessed the safety and efficacy of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and memantine (AD medications), as well as central nervous system drugs (such as antipsychotics and antidepressants) that are frequently used for treating the behavioural symptoms of dementia. However, these trials have been conducted in selected populations. For example, the participants of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitors RCTs were systematically younger and less likely to be women in comparison with a nationwide cohort of persons with AD.4 Comorbidities and concomitant medications were rarely reported in the RCTs, but majority of them excluded persons with, for example, psychotropic or anticholinergic medications,4 although these medications are commonly used in real life.5 Further, the follow-up times of RCTs are also often short in comparison with the actual time the real-life users are exposed to these medications6 7 and the RCT sample sizes do not necessarily allow the detection of rarer adverse events which, however, would be significant on a population level.

People with AD are particularly vulnerable, and older people in general are more susceptible to interactions and adverse effects due to ageing-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.8 9 Inappropriate or even appropriate pharmacotherapy can lead to deteriorations in functional capacity and increase the need for hospitalisation, homecare and institutionalisation, so it is essential to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of medications among actual users. Importantly, decreases in adverse events leading to institutionalisation can translate to a better quality of life for patients and their caregivers, and to more efficient targeting of healthcare resources. Thus, representative studies with adequate follow-up time are needed.

Our aim is to investigate the changes in medication and healthcare service use among persons with AD and to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of medications in this group. For this purpose, we have set up a register-based nationwide Medicine use and Alzheimer's disease (MEDALZ) study which includes all community-dwellers who received a clinically verified AD diagnosis between 2005 and 2011. Reliable, continuously updated individual-level data on hospitalisations since 1972 and medications since 1995 makes this cohort a unique possibility to assess the changes in medications and health status before and after AD diagnosis.

Cohort description

MEDALZ contains all residents of Finland who received a clinically verified diagnosis of AD between 2005 and 2011 and were community-dwelling at the time of diagnosis (N=73 005). Cohort members were identified from Special Reimbursement register maintained by the Social Insurance Institution of Finland (SII). As reimbursement was also granted for dementia related to Parkinson disease, we excluded persons with dementia related to Parkinson disease (n=2286), resulting to the final sample size of 70 719. The Finnish Current Care Guideline recommends that all persons with AD are treated with anti-dementia drugs unless there is a specific contraindication (such as gastric ulcer/intestinal tract operation <6 months ago or severe asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors).10 Patients with mild/moderate AD are entitled to reimbursed medication, but the reimbursement is not withdrawn if/when the disease progresses so our cohort includes persons with all stages of AD. To be eligible for reimbursement, AD diagnosis needs to be clinically verified according to the NINCS-ADRDA and DSM-IV criteria for AD.11 12 Summary of anamnestic information from the patients and family, as well as findings from clinical examination and all diagnostic findings, are submitted to the SII, where a geriatrician/neurologist systematically evaluates the diagnostic evidence for each AD case and confirms whether the prespecified criteria are met. Thus all AD cases of the cohort were verified by medical examination including CT/MRI scan, exclusion of alternative diagnoses and confirmation of AD diagnosis by a geriatrician or neurologist. The physician also needs to confirm whether the patient has other dementing diseases, such as mixed dementia, multi-infarct dementia or Lewy body dementia. However, patients with these diseases are also entitled to reimbursed medicines if the symptoms are considered to be mainly caused by AD.

Finland (population 5.4 million, gross domestic product ∼€38 000 per capita in 2014) has a similar population structure to other developed countries: in 2015, 19.9% of the population was 65 years or older, and this percentage is expected to increase up to 26% by 2050 (Statistics Finland). For those born in 2014, life expectancy was 83.9 years for girls and 78.2 years for boys. Data on medication and healthcare service use are collected routinely. The healthcare system is organised according to a national framework, set by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. All citizens/residents are covered by tax-supported public health service and have unrestricted access to health services, regardless of their socioeconomic status.13

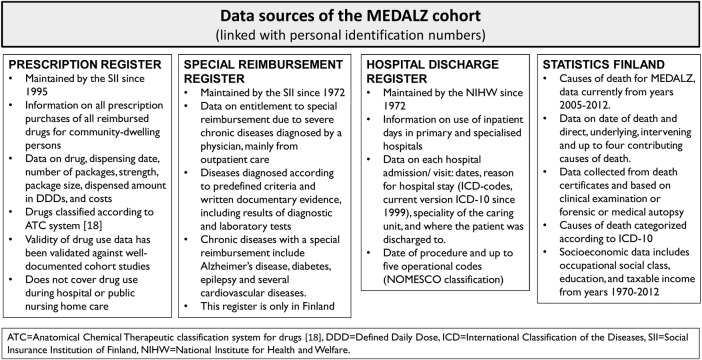

The MEDALZ cohort contains socioeconomic data (education, occupational status and taxable income, 1972–2012) and causes of death data from Statistics Finland (2005–2012), data from the prescription register (1995–2012), the special reimbursement register (1972–2012) and the hospital discharge register (1972–2012). Data on stays in long-term facilities (1995–2012) were obtained from SII. The registers have been described in detail in our pilot study that included all Finnish AD cases alive as on 31 December 2005.14 The available data are listed in figure 1. Briefly, we have extracted detailed diagnosis history from the hospital discharge register and also derived data on cumulative costs of hospital days and prescribed medications.15 16 The prescription purchase data have been transformed to medication use periods, that is, how long each person used each medication, using the PRE2DUP method.17 Briefly, the method uses a decision procedure that includes each person's purchase history for each ATC code,18 processed in a chronological order. The method constructs exposure periods and estimates the dose used during the period by considering the purchased amount in defined daily doses, recorded in the prescription register. PRE2DUP accounts for stockpiling of medications, personal purchasing pattern that is, regularity of the purchases, as well as hospitalisations and stays in long-term facilities when medication use is not recorded in the prescription register. The method is constantly developed further and new features are added according to research interests.

Figure 1.

Data sources used in the MEDALZ cohort. MEDALZ, Medicine use and Alzheimer's disease; NOMESCO, Finnish version of the Nordic Medico-Statistical Committee classification for Surgical Procedures.

The study protocol was approved by the register maintainers (figure 1). Data were retrieved by the register maintainers on the basis of personal identification numbers (PINs), but all data were de-identified before submission to the research team, that is, PINs were replaced by research ids, enabling the data linkage and updates. According to Finnish law, additional ethics committee approval or informed consent was not required. According to the Personal Data Act, informed consent is not needed because we are using only routinely collected, anonymised data and participation in the study does not affect treatment.

Currently, the follow-up data are available until 31 December 2012 but we are planning future updates. At present, the average length of follow-up after diagnosis is 3.1 years. Altogether 26 045 (36.8%) persons died during the follow-up. The average age at the date of diagnosis was 80.05 years (95% CI 80.00–80.11 years, range 34.5–104.6 years).

The characteristics of the MEDALZ cohort are described in table 1. The majority (65.2%) were women and the number of AD cases increased annually, from 8547 (12.1% of the cohort) in 2005 to 12 222 (17.3% of the cohort) in 2011. Approximately half of the cohort had a history of some type of cardiovascular disease and 86.1% had purchased related cardiovascular medication before the follow-up. History of mental and behavioural disorders was relatively common, with 23.1% having hospital admission due to these diseases before AD diagnosis. However, admissions due to dementia are also included in this category. Approximately one-tenth of the cohort had medically treated diabetes and asthma/COPD or hospitalisations due to these diseases.

Table 1.

Description of the MEDALZ cohort (N=70 719) at baseline (date of AD diagnosis).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Men | 24 602 (34.8) |

| Women | 46 117 (65.2) |

| Year of AD diagnosis | |

| 2005 | 8547 (12.1) |

| 2006 | 8803 (12.5) |

| 2007 | 9442 (13.4) |

| 2008 | 10 327 (14.6) |

| 2009 | 10 500 (14.9) |

| 2010 | 10 878 (15.4) |

| 2011 | 12 222 (17.3) |

| Highest occupational social class during 1972-AD diagnosis | |

| Managerial/professional | 14 680 (20.8) |

| Office worker | 5974 (8.5) |

| Farming/forestry | 13 443 (19.0) |

| Sales/industry/cleaning | 30 150 (42.6) |

| Unknown | 5932 (8.4) |

| Did not respond | 540 (0.8) |

| Highest socioeconomic position recorded for study participants in their middle age (age 45–55 years) | |

| Entrepreneurs and higher clerical workers | 24 164 (34.2) |

| Lower clerical workers and employees | 40 895 (57.8) |

| Unemployed, conscripts, retired and students | 4830 (6.8) |

| Unknown/missing | 829 (1.2) |

| History of comorbidities | |

| Cardiovascular disease (special reimbursement register) | 35 921 (50.8) |

| Hospitalisation due to ischaemic heart disease (ICD-10 code I20-I25) | 18 468 (26.1) |

| Hospitalisation due to stroke (ICD-10 code I60-I64) | 6828 (9.7) |

| Diabetes (special reimbursement register) | 9461 (13.4) |

| Hospitalisation due to diabetes (ICD-10 code E10-E14) | 7384 (10.4) |

| Asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (special reimbursement register) | 6199 (8.8) |

| Hospitalisation due to asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-10 code J44-J46) | 5267 (7.5) |

| Hospitalisation due to hip fracture (ICD10-code S720-S721) | 3714 (5.3) |

| Hospitalisation due to any mental or behavioural disorder (ICD-10 code F*) | 16 668 (23.6) |

| Disorders due to psychoactive substance use (ICD-10 code F1*) | 1832 (2.6) |

| Schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (ICD-10 code F2*) | 1882 (2.7) |

| Depression (ICD-10 code F32-F34, F38-F39) | 3760 (5.3) |

| Mania and bipolar disorder (ICD-10 code F30-F31) | 504 (0.8) |

| Neurotic, stress-related and somatoform disorders (ICD-10 code F4*) | 1756 (2.5) |

| Disorders of adult personality and behaviour (ICD-10code F6*) | 270 (0.4) |

| History of medication use | |

| Any antipsychotic (ATC-code N05A) | 12 009 (17.0) |

| Any antiepileptic medication (ATC-code N03A) | 7176 (10.1) |

| Any opioids (ATC-code N02A) | 17 381 (24.6) |

| Any antidepressants (ATC-code N06A) | 22 984 (32.5) |

| Benzodiazepines (ATC codes N05BA, N05CD, N05CF) | 31 424 (44.4) |

| Any diabetes drug (ATC code A10) | 13 433 (19.0) |

| Any CVD drug (ATC code C*) | 60 856 (86.1) |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; ATC, Anatomical Chemical Therapeutic classification system; CVD, cardiovascular disease; ICD 10, International Classification of Disease; 10th Edition; MEDLAZ, Medicine use and Alzheimer's disease.

The study participants made 18.3 million reimbursed drug purchases between 1995 and 2012. These purchases were modelled into 3.9 million use periods, lasting total 4.2 million years. Altogether 17.0% had used antipsychotics, 32.5% antidepressants and 44.4% benzodiazepines before the AD diagnosis. More detailed description of the medication use in this cohort is available in references.5 19 20

Findings to date

Altogether 53% of the MEDALZ cohort had used psychotropic drugs within 1 year of AD diagnosis, which was considerably higher than that among matched comparison persons without AD, of whom 33% used these drugs.5 Similarly, when compared to a matched cohort without AD, persons with AD initiated benzodiazepine and related drug use more frequently already 1 year before AD diagnosis, with the highest rate of initiations at 6 months after the AD diagnosis.20 The initiation of antidepressants was already common 9 years before the AD diagnosis in comparison to a matched cohort without AD.19 As observed with benzodiazepines, the initiation rate of antidepressants peaked at 6 months after AD diagnosis. We are currently assessing if these, and other commonly used medications are related to adverse events.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, a similar nationwide cohort of clinically verified AD cases does not exist elsewhere in the world. PINs and the Finnish statutory healthcare and prescription registers provide excellent research resource, as data on, for example, sociodemographic characteristics, diagnoses and hospitalisations, medications and mortality can be obtained and linked with relative ease. Similar systems are used in other Nordic countries, but so far it has not been possible to identify all AD cases in these countries. The main prerequisite of register-based studies is good coverage and validity of the data sources. Studies assessing the internal validity of Finnish administrative registers21 and comparing register information with patient records or other information from the primary source have confirmed that the coverage and accuracy of these registers are well-suited for epidemiological research.22–29 We acknowledge that the reliability of hospital discharge register varies between diseases, with the more severe ones (such as strokes, schizophrenia or hip fractures) being more accurately captured than conditions that are also treated in outpatient settings (eg, diabetes and mild or moderate depression). However, for the latter ones, the hospital discharge register will capture the most severe cases. In addition, the special reimbursement register captures also the outpatient diagnoses of many diseases, such as for example, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and asthma/COPD. Most importantly, the validity of these diagnoses in the special reimbursement register is high as diagnoses are based on explicit, predefined criteria. One limitation of our cohort is that it is restricted to AD cases and mixed dementia cases whose symptoms are deemed to be mainly due to AD. Thus, it does not represent all dementia cases. However, AD is the most common form, accounting for 60–80% of all dementia cases.2

Special reimbursement for AD medication was introduced in 1999 and the prevalence of AD is underestimated in the register data from early years. Thus we restricted the MEDALZ study to diagnoses from 2005 onwards. These newer data have better correlation with the true prevalence and incidence. Owing to explicit diagnostic criteria, positive predictive value of AD diagnosis is high.30 In our pilot study including all Finnish AD cases who were community-dwelling as on 31 December 2005, the association of diabetes and AD and AD and hip fracture31 32 was of similar magnitude as in previous observational studies,33–37 supporting the reliability and external validity of these data.

The main limitation of all register-based studies, not specific to ours, is the lack of information on certain confounders, such as body composition, smoking or alcohol use. However, the latter are difficult to measure accurately in general. To some extent, these can be captured by using medical histories as proxy measure, but this can also be accounted for by the within-subject study design that controls for fixed, unmeasured confounding.

Collaboration

We have ongoing international collaborations and are open for new proposals. We have agreed to comply with the regulations of register maintainers (SII and National Institute of Health and Welfare) which limit the use of data to strictly non-commercial purposes and restrict the data access to only those persons who are entitled to have access to the data according to accepted research proposals. Thus, new permissions for each individual accessing the data need to be filed. In addition, data provided by the National Institute of Health and Welfare, such as information on hospital discharges and social service use cannot be sent abroad.

Footnotes

Contributors: A-MT drafted the manuscript and analysed data. All authors participated in the study design, revised the article and agreed with the final version and findings.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Barber RM, Foreman KJ et al. GBD 2013 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 306 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 188 countries, 1990–2013: quantifying the epidemiological transition . Lancet 2015;386:2145–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61340-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alzheimer's Association. 2016 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures . Alzheimers Dement 2016;12:459–509. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva: WHO. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leinonen A, Koponen M, Hartikainen S. Systematic review: representativeness of participants in RCTs of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors . PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0124500 10.1371/journal.pone.0124500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taipale H, Koponen M, Tanskanen A et al. High prevalence of psychotropic drug use among persons with and without Alzheimer's disease in Finnish nationwide cohort. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2014;24:1729–37. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taipale H, Tanskanen A, Koponen M et al. Antidementia drug use among community-dwelling individuals with Alzheimer's disease in Finland: a nationwide register-based study . Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2014;29:216–23. 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koponen M, Taipale H, Tanskanen A et al. Long-term use of antipsychotics among community-dwelling persons with Alzheimer's disease: a nationwide register-based study . Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2015;25:1706–13. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2015.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cusack BJ. Pharmacokinetics in older persons. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2004;2:274–302. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangoni AA, Jackson SH. Age-related changes in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: basic principles and practical applications. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2004;57:6–14. 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2003.02007.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Working group appointed by the Finnish Medical Society Duodecim, Societas Gerontologica Fennica, the Finnish Neurological Society, Finnish Psychogeriatric Association and the Finnish Association for General Practice. Finnish current care recommendation: Memory disorders. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–44. 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M et al. The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research . Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010;106:86–94. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00494.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tolppanen AM, Taipale H, Koponen M et al. Use of existing data sources in clinical epidemiology: Finnish healthcare registers in Alzheimer's disease research—the Medication use among persons with Alzheimer's disease (MEDALZ-2005) study . Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:277–85. 10.2147/CLEP.S46622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taipale H, Purhonen M, Tolppanen AM et al. Hospital care and drug costs from five years before until two years after the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease in a Finnish nationwide cohort . Scand J Public Health 2016;44:150–8. 10.1177/1403494815614705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tolppanen AM, Taipale H, Purmonen T et al. Hospital admissions, outpatient visits and healthcare costs of community-dwellers with Alzheimer's disease . Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:955–63. 10.1016/j.jalz.2014.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanskanen A, Taipale H, Koponen M et al. From prescription drug purchases to drug use periods—a second generation method (PRE2DUP) . BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2015;15:21 10.1186/s12911-015-0140-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2012. (accessed 15 Mar 2012).

- 19.Puranen A, Taipale H, Koponen M et al. Incidence of antidepressant use in community-dwelling persons with and without Alzheimer's disease—13-year follow-up . Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2016. 10.1002/gps.4450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saarelainen L, Taipale H, Koponen M et al. The incidence of benzodiazepine and related drug use in persons with and without Alzheimer's disease . J Alzheimers Dis 2015;49:809–18. 10.3233/JAD-150630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gissler M, Shelley J. Quality of data on subsequent events in a routine Medical Birth Register . Med Inform Internet Med 2002;27:33–8. 10.1080/14639230110119234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isohanni M, Makikyro T, Moring J et al. A comparison of clinical and research DSM-III-R diagnoses of schizophrenia in a Finnish national birth cohort. Clinical and research diagnoses of schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1997;32:303–8. 10.1007/BF00789044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teppo L, Pukkala E, Lehtonen M. Data quality and quality control of a population-based cancer registry. Experience in Finland. Acta Oncol 1994;33:365–9. 10.3109/02841869409098430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tolonen H, Salomaa V, Torppa J et al. The validation of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register and Causes of Death Register data on stroke diagnoses . Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:380–5. 10.1097/01.hjr.0000239466.26132.f2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meretoja A, Kaste M, Roine RO et al. Trends in treatment and outcome of stroke patients in Finland from 1999 to 2007. PERFECT Stroke, a nationwide register study. Ann Med 2011;43(Suppl 1):S22–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sund R, Nurmi-Lüthje I, Lüthje P et al. Comparing properties of audit data and routinely collected register data in case of performance assessment of hip fracture treatment in Finland. Methods Inf Med 2007;46:558–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mähönen M, Salomaa V, Torppa J et al. The validity of the routine mortality statistics on coronary heart disease in Finland: comparison with the FINMONICA MI register data for the years 1983–1992. Finnish multinational MONItoring of trends and determinants in CArdiovascular disease. J Clin Epidemiol 1999;52:157–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pajunen P, Koukkunen H, Ketonen M et al. The validity of the Finnish Hospital Discharge Register and Causes of Death Register data on coronary heart disease. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2005;12:132–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rapola JM, Virtamo J, Korhonen P et al. Validity of diagnoses of major coronary events in national registers of hospital diagnoses and deaths in Finland. Eur J Epidemiol 1997;13:133–8. 10.1023/A:1007380408729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon A, Ngandu T, Soininen H et al. Validity of dementia and Alzheimer disease diagnoses in Finnish national registers . Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:303–9. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tolppanen AM, Lavikainen P, Solomon A et al. History of medically treated diabetes and risk of Alzheimer disease in a nationwide case–control study . Diabetes Care 2013;36:2015–9. 10.2337/dc12-1287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tolppanen AM, Lavikainen P, Soininen H et al. Incident hip fractures among community dwelling persons with Alzheimer's disease in a Finnish nationwide register-based cohort . PLoS ONE 2013;8:e59124 10.1371/journal.pone.0059124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Profenno LA, Porsteinsson AP, Faraone SV. Meta-analysis of Alzheimer's disease risk with obesity, diabetes, and related disorders . Biol Psychiatry 2010;67:505–12. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weller I, Schatzker J. Hip fractures and Alzheimer's disease in elderly institutionalized Canadians . Ann Epidemiol 2004;14: 319–24. 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y, Kuo TC, Weir S et al. Healthcare costs and utilization for Medicare beneficiaries with Alzheimer's . BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:108 10.1186/1472-6963-8-108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker NL, Cook MN, Arrighi HM et al. Hip fracture risk and subsequent mortality among Alzheimer's disease patients in the United Kingdom, 1988-2007 . Age Ageing 2011;40:49–54. 10.1093/ageing/afq146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Trimpou P, Landin-Wilhelmsen K, Odén A et al. Male risk factors for hip fracture-a 30-year follow-up study in 7,495 men . Osteoporos Int 2010;21:409–16. 10.1007/s00198-009-0961-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]