Abstract

Objective

We aimed to establish the cut-off point of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA-Beijing) in screening for cognitive impairment (CI) within 2 weeks of mild stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA).

Methods

A total of 80 acute mild ischaemic stroke patients and 22 TIA patients were recruited. They received the MoCA-Beijing and a formal neuropsychological test battery. CI was defined by 1.5 SD below the established norms on a formal neuropsychological test battery.

Results

Most stroke and TIA patients were in their 50s (53.95±11.43 years old), with greater than primary school level of education. The optimal cut-off point for MoCA-Beijing in discriminating patients with CI from those with no cognitive impairment (NCI) was 22/23 (sensitivity 85%, specificity 88%, positive predictive value=91%, negative predictive value=80%, classification accuracy=86%). The predominant cognitive deficits were characteristic of frontal-subcortical impairment, such as visuomotor speed (46.08%), attention/executive function (42.16%) and visuospatial ability (40.20%).

Conclusions

A MoCA-Beijing cut-off score of 22/23 is optimally sensitive and specific for detecting CI after mild stroke, and TIA in the acute stroke phase, and is recommended for routine clinical practice.

Keywords: mild stroke, transient ischemic attack, cognitive impairment, Montreal Cognitive Assessment-Beijing

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to establish the cut-off point of a cognitive screening instrument (Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)-Beijing) against a ‘gold standard’ neuropsychological evaluation in Chinese patients with mild stroke and transient ischaemic attack within 2 weeks after index cerebrovascular event.

A cut-off point of 22/23 on MoCA-Beijing provided good sensitivity and specificity.

The study was limited by its small sample size (n=102), thereby not permitting the examination of age-adjusted and education-adjusted cut-off points.

Introduction

Non-disabling cerebrovascular events, which include mild ischaemic stroke (median National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)=2, median modified Rankin Score (mRS)=2))1 and transient ischaemic attack (TIA), generally result in either short-lasting or mild neurological symptoms,1 but these patients are at an increased risk of a recurrent cerebrovascular event. The patients therefore receive considerable medical attention and treatment for physical symptoms and risk factors. However, their cognitive function is often neglected, especially in the acute stroke phase. In China, there are approximately 9 million patients diagnosed with mild stroke every year.2 A recent study has shown that the prevalence of TIA is 2.27%.3 This is a major public health problem which has increased the healthcare and economic burden, especially when cognitive impairment (CI) is taken into consideration. CI after stroke/TIA has a reported prevalence ranging from 21% to 70%.4 About one in three patients with TIA has an impairment of ≥1 cognitive domain(s) within 3 months after TIA.5 Therefore, early detection of CI at acute stroke phase is the first step to an intensive reduction of vascular risk factors and improved prognosis.6

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a brief cognitive instrument recommended for screening for CI in patients with stroke or TIA.7 Several studies have compared the discriminant abilities of the MoCA and the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for screening post-stroke CI, and most studies have demonstrated that the MoCA is superior or equivalent to the MMSE for the detection of CI after stroke.6 8–13 Furthermore, the MoCA has been reported to be sensitive to changes in acute temporary CI after mild stroke/TIA, whereas, the MMSE is reportedly not.11 On the other hand, a recent meta-analysis showed that all CI screening tests performed similarly in patients with stroke.12 The MoCA at its conventional cut-off point (<26/30), has excellent sensitivity (0.95) but suboptimal specificity (0.45). By comparison, the adapted MoCA cut-off point (<22/30) improved specificity (0.78) while maintaining good sensitivity (0.84). However, there is no data on the discriminant ability of the MoCA for detecting CI determined by a formal neuropsychological evaluation in the Chinese population at the acute stroke phase. Therefore, this study validates the Chinese Beijing version of the MoCA (MoCA-Beijing) against a ‘gold’ standard neuropsychological evaluation to detect CI after acute mild stroke and TIA.

Methods

Participants

Patients were recruited consecutively from the stroke ward in the Department of Neurology, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China, from 1 December 2014 to 30 July 2015.

The inclusion criteria for patients were 18 years of age or older, with an ischaemic mild stroke or TIA within 7 days. Patients' stroke/TIA were diagnosed by neurologists, and confirmed with brain CT or MRI. An eligible patient also had an available informant who was knowledgeable about the patient's medical history and cognitive status, and had met the patient on a weekly basis for at least 5 years prior to the recruitment. The acute ischaemic stroke was diagnosed according to WHO criteria.1 14 TIA was defined by the American Stroke Association.15

The exclusion criteria for patients were stroke mimics (ie, seizures, migraine), illiteracy or any major physical and mental conditions that may impede cognitive assessments. Out of the 119 consecutive patients with stroke who were approached, a majority of patients were recruited into our study (n=102). The reasons for exclusion (n=17) were as follows: major depression defined by a Hamilton Depression Rating Score16 ≥17 (n=8), severe hearing impairment (n=4), achromatopsia (n=3) and illiteracy (n=2). Of the sample of 102, were comprised 80 patients with acute mild stroke and 22 patients with TIA.

This study was approved by the Beijing Tiantan Hospital ethics review board. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants.

Procedure

Demographics and clinical profile

Demographic information including age, sex, educational level, cardiovascular risk factors as well as clinical information, was collected. The severity of neurological impairment was evaluated by the NIHSS17 within 24 hours after admission. The aetiological subtypes of ischaemic stroke were identified as large atherothrombotic infarction (LAA), cardiogenic embolism (CE), artery occlusion (SAO), undetermined type (UND), and other type (OC), according to the Trial of ORG 10 172 in Acute Stroke Treatment criteria.18 All patients underwent brain MRI on a 3.0 T MR scanner. Imaging sequences included three-dimensional time-of-flight MR angiography (MRA), axial T2-weighted, T1-weighted imaging, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery sequences and diffusion-weighted imaging. All the above sequences, except MRA, had a 5 mm slice thickness and a 1.5 mm interslice gap.

Neuropsychological assessment

A formal battery of neuropsychological tests in line with the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the Canadian Stroke Network7 neurocognitive harmonisation standards were included to establish CI. This test battery was administered by trained neurologists and was completed within 14 days after the acute stroke/TIA.7 The average assessment time from the index event was 10 days (median 2 days). The individual tests of the formal battery of neuropsychological test battery are as follows: (1) Auditory Verbal Learning Test for immediate and delay verbal memory;19 (2) Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (RCFT)-delayed Recall for visual memory;20 (3) RCFT copy for visuospatial ability;20 (4) Animal Fluency Test21 and Boston Naming Test (30 item)22 for language; (5) Symbol Digit Modalities Test for visuomotor speed;23 (6) Chinese modified version of the Trail Making Test (TMT)-A,24 TMT-B,24 Stroop Color-Word Test-Chinese version (CWT)-Color and Stroop CWT-C correct numbers24 for attention/executive function.

The MoCA-Beijing25 requires educational adjustment, that is, one point was added to the total score for those with education <12 years.26 The modification of MoCA-Beijing from the original MoCA were: (1) visuospatial/executive function domain: the alphabet letters are replaced with Chinese characters (甲/乙/丙/丁/戊) which contain the same sequential meanings as ‘A/B/C/D/E’ in English; (2) attention domain: numbers are used instead of English alphabet letters; (3) language domain: in the verbal fluency task, the phonemic fluency task that requires participants to generate words beginning with the letter F is replaced by the semantic fluency task requiring participants to produce as many animals as possible in 60 s. Using the conventional cut-off score of <26, the MoCA-Beijing demonstrated an excellent sensitivity of 90.4%, however, suboptimal specificity was of 31.3%.27 The formal battery of neuropsychological tests and MoCA-Beijing were conducted at the same time, and the formal battery of neuropsychological tests were administered by trained neurologists blinded to the MoCA scores.

Functional assessment

Basic daily functioning was assessed by the Katz basic activities of daily living (basic ADL) scale,28 with six basic items, and complex function was assessed by Lawton and Brody instrumental activities of daily living (instrumental ADL) scale,29 with eight instrumental items. Four levels of grading of ADLs were adopted for assessment:1=independent; 2=need for supervision; 3=need for help; 4=unable. The total scores range from 14 to 56. Total scores of ≥16 reflect impaired Alzheimer's disease, with higher scores on the ADL scale indicating more severe impairment of daily functioning.

Diagnosis of vascular cognitive impairment

Cognitive impairment was diagnosed according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-4).30 Education-adjusted cut-offs of 1.5 SD below the established norms of neuropsychological tests support the diagnosis of CI.31 The norms used were based on a normative study of healthy, cognitively normal, community-dwelling, older adults in China.24 A patient with scores of all the individual neuropsychological tests within the normal range was considered to have no cognitive impairment (NCI).

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS Statistics V.20.0 (USA). Between-group comparisons were conducted by using independent sample t-tests for quantitative variables, and a Pearson χ test for categorical variables. Continuous variables, if they were normally distributed, were presented as means±SDs and compared with a two-tailed t-test between two groups. Continuous variables, if they were not normally distributed, were presented as median (quartile) and compared with non-parametric tests. Categorical variables were compared with a χ2 test. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with area under the curve (AUC) was used to compare the discriminatory ability of the MoCA-Beijing in detecting CI.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

According to the test diagnostic accuracy criteria, the STARDem,32 the flowchart of the study population is shown in figure 1. The average age of recruited patients was 53.95±11.43 years, with the majority of patients being men (66.67%). The median of NIHSS score in patients with acute mild stroke was 1.00 point (IQR: 2.00 point(s)). Among the 80 patients with acute mild stroke, approximately half had SAO (n=38, 47.5%), followed by LAA (n=30, 37.5%), CE (n=4, 5.0%), OC (n=4, 5.0%) and UND (n=4, 5.0%). More than half of the sample (58.82%) had cognitive impairment as determined by the formal battery of neuropsychological tests (table 1).

Figure 1.

STARD flow diagram of patient recruitment. *Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) abnormal result ≤22 (n=56); +MoCA normal result >22 (n=46); #Reference test: neuropsychological battery. §Target condition: cognitive impairment (n=60).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with acute mild stroke or TIA within 2 weeks after onset

| Total | No cognitive impairment (NCI) | Cognitive impairment (CI) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 102 | 42 | 60 | |

| Sex, male (%) | 68/102 (66.67) | 29/42 (69.05) | 39/60 (65.00) | 0.77 |

| Age, year, mean (SD)* | 53.95 (11.43) | 47.70 (10.49) | 58.25 (10.04) | <0.001** |

| NIHSS at admission | 0.46 | |||

| Median (IQR) | 1.00 (2.00) | 1.00 (3.00) | 2.00 (2.00) | |

| Premorbid mRS median (IQR) | 0.05 (0.34) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.05 (0.29) | 0.76 |

| Baseline mRS median (IQR) | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.00 (1.00) | 0.19 |

| Education* | 0.02* | |||

| Primary school and below (%) | 12/102 (11.76) | 3/42 (7.14) | 9/60 (15.00) | |

| Middle and high school (%) | 74/102 (72.55) | 28/42 (66.67) | 46/60 (76.67) | |

| Bachelor and above (%) | 16/102 (15.69) | 11/42 (26.19) | 5/60 (8.33) | |

| Stroke classification* | 0.046* | |||

| LAA (%) | 30/80 (37.50) | 10/32 (31.25) | 20/48 (41.67) | |

| CE (%) | 4/80 (5.00) | 3/32 (9.38) | 1/48 (2.08) | |

| SAO (%) | 38/80 (47.50) | 13/32 (40.63) | 25/48 (52.08) | |

| OC (%) | 4/80 (5.00) | 3/32 (9.37) | 1/48 (2.08) | |

| UND (%) | 4/80 (5.00) | 3/32 (9.37) | 1/48 (2.08) | |

| TIA (%) | 22/102 (21.57) | 10/42 (23.81) | 12/60 (20.00) | 0.56 |

| Medical history, n (%) | ||||

| Number of risk factors, mean (SD) | 4.57 (2.03) | 4.12 (1.84) | 4.88 (2.11) | 0.55 |

| Hypertension* (%) | 68/102 (66.67) | 23/42 (54.76) | 45/60 (75.00) | 0.03* |

| Impaired glucose regulation (%) | 34/102 (33.33) | 15/42 (35.71) | 19/60 (31.67) | 0.18 |

| Hyperlipidaemia (%) | 79/102 (77.45) | 35/42 (83.33) | 44/60 (73.33) | 0.54 |

| Atrial fibrillation (%) | 8/102 (7.84) | 3/42 (7.14) | 5/60 (8.33) | 0.72 |

| Coronary heart disease (%) | 12/102 (11.76) | 5/42 (11.90) | 7/60 (11.67) | 0.99 |

| Hyperhomocysteinaemia (%) | 28/102 (27.45) | 10/42 (23.81) | 18/60 (30.00) | 0.65 |

| Peripheral arterial disease (%) | 21/102 (20.59) | 7/42 (16.67) | 14/60 (23.33) | 0.47 |

| Current or ever drinking (%) | 73/102 (71.57) | 31/42 (73.81) | 42/60 (70.00) | 0.82 |

| Current or ever smoking (%) | 69/102 (67.65) | 31/42 (73.81) | 38/60 (63.33) | 0.81 |

| Family history of stroke (%) | 30/79 (37.97) | 9/32 (28.13) | 21/47 (44.68) | 0.16 |

| Prior subcortical stroke or TIA (%) | 15/102 (14.71) | 4/42 (9.52) | 11/60 (18.33) | 0.27 |

| Anterior circulation (%) | 57/102 (55.88) | 19/42 (45.24) | 38/60 (63.33) | 0.11 |

| Posterior circulation (%) | 45/102 (44.12) | 23/42 (54.76) | 22/60 (36.67) | 0.07 |

| Functional status | ||||

| mRS score | 0.00 (0.00∼1.00) | 1.00 (1.00∼2.00) | 1.00 (0.00–3.00) | 0.99 |

| Instrumental ADL | 8.85 (3.08) | 8.08 (0.47) | 9.49 (0.58) | 0.019* |

| Basic ADL | 5.57 (2.58) | 5.88 (0.95) | 5.37 (0.42) | 0.23 |

Mild stroke and TIA patients were divided into cognitive impairment group and no cognitive impairment group according to a battery of neurological tests, including Auditory Verbal Learning Test, Animal Fluency Test, Symbol Digital Modalities Test, Trail Making Test, Stroop Color-Word Test, Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test and Boston Naming Test.

*p<0.05; **p<0.01.

basic ADL, basic activities of daily living; CE, cardioembolism; HAMD, Hamilton depression scale; instrumental ADL, instrumental activities of daily living; LAA, large artery atherosclerosis; mRS, Modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS, National Institute of Health Stroke Scale; OC, stroke of other determined cause; SAO, small artery occlusion; TIA, transient ischaemic attack; UND, undetermined aetiology.

Demographic information showed that the NCI and CI groups were similar except for age, education, stroke classification, prevalence of hypertension and instrumental ADL. Multivariate analysis showed that age was a significant predictor for CI after minor stroke/TIA (table 1).

The discriminant ability of MoCA-Beijing

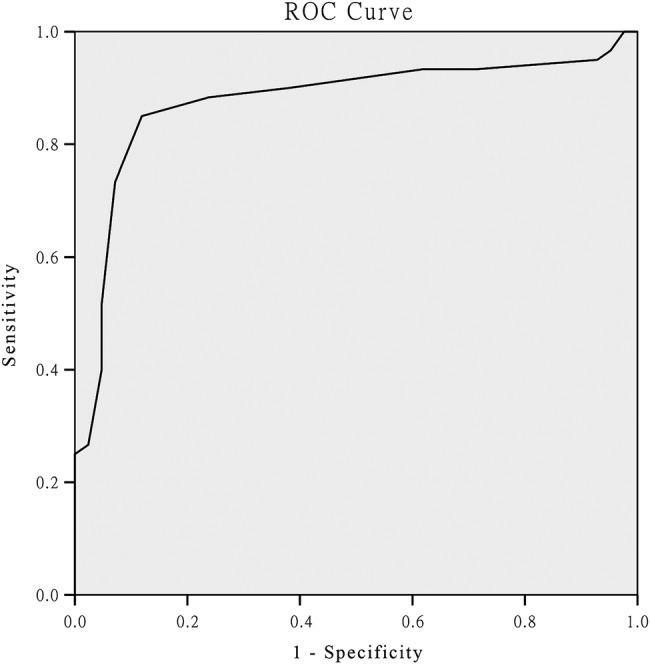

Using ROC analysis, a cut-off point of MoCA-Beijing ≤22 was established to best discriminate CI from NCI (table 2). The AUC of MoCA-Beijing was 0.85 (95% CI (0.80 to 0.95)) with good sensitivity (0.85) and specificity in detecting CI (0.88) (figure 2).

Table 2.

Discriminant indices of MoCA in detecting cognitive impairment in patients with acute mild stroke and TIA within 2 weeks after onset

| MoCA | Se % | Sp % | PPV % | NPV % | Correctly classified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20/21 | 0.98 | 0.58 | 0.94 | 0.58 | 0.70 |

| 21/22 | 0.95 | 0.72 | 0.94 | 0.71 | 0.81 |

| 22/23* | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.80 | 0.86 |

| 23/24 | 0.76 | 0.86 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| 24/25 | 0.52 | 0.93 | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.78 |

*Optimal cutoff score. MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; Se, sensitivity; Sp, specificity; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis of Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for differentiating patients with cognitive impairment from patients without cognitive impairment (22.5; sensibility 85%, specificity 88%, area under curve=0.86).

Characteristics of neuropsychological impairment

The predominantly impaired cognitive domains were visuomotor speed (n=47, 46.08%), followed by attention/executive function (n=43, 42.16%), visuospatial ability (n=41, 40.20%), visual memory (n=31, 30.39%), language (n=26, 25.49%), verbal immediate-memory (n=31, 22.55%) and verbal delay-memory (n=17, 16.67%) (table 3).

Table 3.

Percentage of each impaired cognitive domain in total patients with acute mild stroke and transient ischaemic attack

| Cognitive domain | Percentage of patients with impaired cognitive domain (%) |

|---|---|

| Global cognition | 55/102 (53.92) |

| Visuomotor speed | 47/102 (46.08) |

| Attention/executive function | 43/102 (42.16) |

| Visuospatial ability | 41/102 (40.20) |

| Visual memory | 31/102 (30.39) |

| Language | 26/102 (25.49) |

| Verbal immediate-memory | 23/102 (22.55) |

| Verbal delay-memory | 17/102 (16.67) |

Discussion

For the first time, our study used the MoCA-Beijing to screen for cognitive impairment in Chinese patients with mild stroke and TIA in the acute phase. The cut-off point of MoCA-Beijing at 22/23 provided good sensitivity (85%) and specificity (88%) (table 4). As recommended by The National Institute of Excellence guidelines,33 MoCA administration within 2 weeks after the mild stroke or TIA event can identify cognitive deficits for early intervention and focused management. Our data provides a useful reference point for a Chinese population.

Table 4.

A cross-tabulation of the results of the index tests by the results of the reference standard

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychological tests | ≤22 | >22 |

| Cognitive impairment | 51 | 9 |

| No cognitive impairment | 5 | 37 |

The MoCA cut-off score (MoCA-Beijing ≤22) in our study was lower than the commonly recommended cut-off point of 26,26 which may be due to several reasons. First, patient population was different in the original MoCA study by Nasreddine et al,26 which recruited 94 MCI or 93 AD patients and 90 controls, while we recruited 102 patients with acute mild stroke/TIA. Second, the education level and age were different between patient samples in the original MoCA study and the present study (education: senior high school vs junior high school; age: 70s vs 50s). Third, the diagnostic criteria for cognitive impairment were different. In the original MoCA study, in which a cut-off of 26 yielded a sensitivity of 0.90 and a specificity of 0.87 to detect MCI, the diagnosis was mainly determined by the memory tests, whereas our neuropsychological test battery included tests covering a number of cognitive domains. These differences in diagnostic criteria might also have contributed to the differences in the cut-off points derived for MoCA. Similarly, other studies on cognitive screening in stroke/TIA patients reported discrepant cut-off MoCA scores from the conventional cut-off point recommended by Nasreddine and colleagues.9 A French study reported the same MoCA cut-off point (≤22) as our own, with good sensitivity (0.84) and specificity (0.81).6 Additionally, a recent meta-analysis reported that MoCA at its conventional cut-off point (<26/30) had excellent sensitivity (0.95) but low specificity (0.45). By comparison, adapted MoCA cut-off point (≤22/30) improved specificity (0.88) while maintaining good sensitivity (0.85).

Our study found that visuomotor speed was the most frequently impaired domain, followed by attention/executive function, visuospatial ability, visual memory, language and verbal memory in patients with acute stroke/TIA. This is consistent with previous studies which report similar characteristics of neuropsychological impairment in patients with stroke.5

However, our study has some limitations. First, the sample size is relatively small, with the cohort of our patients with stroke being younger than in previous studies. Patients with stroke who were admitted from December 2014 to July 2015 to the Beijing Tiantan Hospital, which is the National Clinical Research Center for Neurological Diseases in China, were aged 53.95±11.43 years. Most patients with stroke admitted in our hospital are non-residents in Beijing, and they are generally younger than the residents in Beijing. Therefore, our findings may not be applicable to all patients with stroke. Second, cognitive function is merely assessed at the acute stroke phase when patients' cognitive functioning is likely to fluctuate as they undergo spontaneous recovery. Thus, these patients will need a follow-up at 3–6 months after stroke, and their cognitive function reassessed when their recovery is stable. Third, the MoCA scores are influenced by age and education. We are unable to derive age-adjusted and education-adjusted MoCA cut-off points. Future study should include a larger sample and develop age-adjusted and education-adjusted cut-off points for MoCA. Last, frequent impairments in attention/executive function could be due to more tests (total 4) in attention/executive function domain, which may be perceived to impose a circularity effect. However, we classified attention and executive function domains as the same. It is psychometrically acceptable to have two tests in a single domain for reliability. Previous studies on cognition after stroke also included similar neuropsychological tests.21 34

In conclusion, the MoCA-Beijing is sensitive and specific in detecting CI in patients with acute mild stroke or TIA. Therefore, it should be implemented in routine clinical practice.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their involvement. They also thank Dr Sophia Dean from the Centre for Healthy Brain and Ageing, School of Psychiatry, the University of New South Wales, Australia, for her review of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: LZ, YW was involved in the drafting and revising of the manuscript, study concept or design, analysis or interpretation of data; they accept responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval for acquisition of data and statistical analysis. YD was involved in the critical revision of the manuscript, assisted with study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research, and will give final approval, verification of some data (neuropsychological test scoring). RZ, ZJ, ZL, XZ, WZ was involved the study concept or design of the manuscript, accept responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval for acquisition of data. YW was involved in the study concept or design, accepts responsibility for conduct of research and will give final approval, statistical analysis, study supervision. PS: assistance with early design, critical review of the analysis and of the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the People's Republic of China (2008ZX09312-008, 200902004, 2011BAI08B01, 2011BAI08B02, 2012ZX09303, and 2013BAI09B03); Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders (BIBD-PXM2013_014226_07_000084); Beijing Municipal Key Laboratory for Neural Regeneration and Repairing (2015SJZS05); the National Key Basic Research Program of China (2011CB504100); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81571229, 81071015, 30770745); the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing, China (7082032); Key Project of Beijing Natural Science Foundation (kz200910025001); National Key Technology Research and Development Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2013BAI09B03); the project of the Beijing Institute for Brain Disorders (BIBD-PXM2013_014226_07_000084); High Level Technical Personnel Training Project of Beijing Health System, China (2009-3-26); the Project of Construction of Innovative Teams and Teacher Career Development for Universities and Colleges Under Beijing Municipality (IDHT20140514); Capital Clinical Characteristic Application Research (Z121107001012161); the Beijing Healthcare Research Project, China (JING-15-2, JING-15-3); Excellent Personnel Training Project of Beijing, China (20071D0300400076); Important National Science and Technology Specific Projects (2011ZX09102-003-01); Key Project of National Natural Science Foundation of China (81030062); Basic-Clinical Research Cooperation Funding of Capital Medical University (10JL49, 14JL15, 2015-JL-PT-X04); and the Youth Research Fund, Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, China (2014-YQN-YS-18, 2015-YQN-15, 2015-YQN-05, 2015-YQN-14, 2015-YQN-17).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Beijing Tiantan Hospital ethics review board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Fischer U, Baumgartner A, Arnold M et al. What is a minor stroke? Stroke 2010;41:661–6. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.572883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhao D, Liu J, Wang W et al. Epidemiological transition of stroke in China: twenty-one-year observational study from the sino-monica-Beijing project. Stroke 2008;39:1668–74. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.502807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Y, Zhao X, Jiang Y et al. Prevalence, knowledge, and treatment of transient ischemic attacks in China. Neurology 2015;84:2354–61. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran GM, Fletcher B, Feltham MG et al. Fatigue, psychological and cognitive impairment following transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke: a systematic review. Eur J Neurol 2014;21:1258–67. 10.1111/ene.12469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Rooij FG, Schaapsmeerders P, Maaijwee NA et al. Persistent cognitive impairment after transient ischemic attack. Stroke 2014;45:2270–4. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Godefroy O, Fickl A, Roussel M et al. Is the Montreal cognitive assessment superior to the mini-mental state examination to detect poststroke cognitive impairment? A study with neuropsychological evaluation. Stroke 2011;42:1712–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hachinski V, Iadecola C, Petersen RC et al. National institute of neurological disorders and stroke-Canadian stroke network vascular cognitive impairment harmonization standards. Stroke 2006;37:2220–41. 10.1161/01.STR.0000237236.88823.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kasai M, Meguro K, Nakamura K et al. Screening for very mild subcortical vascular dementia patients aged 75 and above using the Montreal cognitive assessment and mini-mental state examination in a community: the kurihara project. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2012;2:503–15. 10.1159/000340047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dong Y, Sharma VK, Chan BP et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment (moca) is superior to the mini-mental state examination (mmse) for the detection of vascular cognitive impairment after acute stroke. J Neurol Sci 2010;299:15–18. 10.1016/j.jns.2010.08.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blackburn DJ, Bafadhel L, Randall M et al. Cognitive screening in the acute stroke setting. Age Ageing 2013;42:113–16. 10.1093/ageing/afs116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sivakumar L, Kate M, Jeerakathil T et al. Serial Montreal cognitive assessments demonstrate reversible cognitive impairment in patients with acute transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. Stroke 2014;45:1709–15. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.004726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lees R, Selvarajah J, Fenton C et al. Test accuracy of cognitive screening tests for diagnosis of dementia and multidomain cognitive impairment in stroke. Stroke 2014;45:3008–18. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mai LM, Sposato LA, Rothwell PM et al. A comparison between the moca and the mmse visuoexecutive sub-tests in detecting abnormalities in tia/stroke patients. Int J Stroke 2016;11:420–4. 10.1177/1747493016632238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.[No authors listed] Stroke—1989. Recommendations on stroke prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. Report of the who task force on stroke and other cerebrovascular disorders. Stroke 1989;20:1407–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al., American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American heart association/American stroke association stroke council; council on cardiovascular surgery and anesthesia; council on cardiovascular radiology and intervention; council on cardiovascular nursing; and the interdisciplinary council on peripheral vascular disease. The American academy of neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke 2009;40:2276–93. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr 1960;23:56–62. 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brott T, Adams HP Jr, Olinger CP et al. Measurements of acute cerebral infarction: A clinical examination scale. Stroke 1989;20:864–70. 10.1161/01.STR.20.7.864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adams HP Jr, Bendixen BH, Kappelle LJ et al. Classification of subtype of acute ischemic stroke. Definitions for use in a multicenter clinical trial. Toast. Trial of org 10172 in acute stroke treatment. Stroke 1993;24:35–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo Q, Zhao Q, Chen M et al. A comparison study of mild cognitive impairment with 3 memory tests among Chinese individuals. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:253–9. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181999e92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou YLJ, Guo QH, Hong ZN. Rey-Osterrieth complex figure test used to identify mild Alzheimer's disease. Chin J Clin Neurosci 2006;14:501–4. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma J, Zhang Y, Guo Q. Comparison of vascular cognitive impairment—no dementia by multiple classification methods. Int J Neurosci 2015;125:823–30. 10.3109/00207454.2014.972504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin CY, Chen TB, Lin KN et al. Confrontation naming errors in Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2014;37: 86–94. 10.1159/000354359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong YX. Wechsler adult intelligence scale-Chinese version(wais). Hunan: Hunan Map Press, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo QH SY, Yuan J, Hong Z et al. Application of eight executive tests in participants at shanghai communities. Chin J Behav Med Sci 2007 2007;16:628–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wen HB, Zhang ZX, Niu FS et al. [the application of Montreal cognitive assessment in urban Chinese residents of Beijing]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi 2008;47:36–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V et al. The Montreal cognitive assessment, moca: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:695–9. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu J, Li J, Huang X. The Beijing version of the Montreal cognitive assessment as a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment: a community-based study. BMC Psychiatry 2012;12:156 10.1186/1471-244X-12-156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist 1969;9:179–86. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW et al. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of adl: A standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA 1963;185:914–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th edn (dsm-iv). Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kochan NA, Slavin MJ, Brodaty H et al. Effect of different impairment criteria on prevalence of “objective” mild cognitive impairment in a community sample. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;18:711–22. 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181d6b6a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Noel-Storr AH, McCleery JM, Richard E et al. Reporting standards for studies of diagnostic test accuracy in dementia: the starddem initiative. Neurology 2014;83:364–73. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National institute for health and clinical excellence. Stroke quality standard. London: National institute for health and clinical excellence, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Q, Cao WW, Mi JH et al. Brief screening for mild cognitive impairment in subcortical ischemic vascular disease: a comparison study of the Montreal cognitive assessment with the mini-mental state examination. Eur Neurol 2014;71:106–14. 10.1159/000353988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]