Abstract

Introduction

Recent research suggests that vitamin D deficiency may cause both bone diseases and a range of non-skeletal diseases. However, most of these data come from observational studies, and clinical trial data on the effects of vitamin D supplementation on individuals with pre-diabetes are scarce and inconsistent. The aim of the Diabetes Prevention with active Vitamin D (DPVD) study is to assess the effect of eldecalcitol, active vitamin D analogue, on the incidence of type 2 diabetes among individuals with pre-diabetes.

Methods and analysis

DPVD is an ongoing, prospective, multicentre, randomised, double-blind and placebo-controlled outcome study in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. Participants, men and women aged ≥30 years, will be randomised to receive eldecalcitol or placebo. They will also be given a brief (5–10 min long) talk about appropriate calorie intake from diet and exercise at each 12-week visit. The primary end point is the cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes. Secondary endpoint is the number of participants who achieve normoglycaemia at 48, 96 and 144 weeks. Follow-up is estimated to span 144 weeks.

Ethics and dissemination

All protocols and an informed consent form comply with the Ethics Guideline for Clinical Research (Japan Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare). The study protocol has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Kokura Medical Association and University of Occupational and Environmental Health. The study will be implemented in line with the CONSORT statement.

Trial registration number

UMIN000010758; Pre-results.

Keywords: DIABETES & ENDOCRINOLOGY, CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will provide new evidence concerning the effect of eldecalcitol, active vitamin D, on preventing the incidence of type 2 diabetes in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance.

Our study participants will be at high risk for diabetes; all the participants will visit clinics to be followed by physicians every 12 weeks, and they will be prescribed active vitamin D formulations at that visit. Therefore, the drug compliance and the follow-up ratio in our study will be better than those in other trials, where study participants, almost healthy people, receive vitamin D supplements once a year.

It is unknown whether the results of this study applies to other ethnicities because this study consists of only Japanese participants.

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and causes a variety of complications. Moreover, the incidence of type 2 diabetes is currently increasing and has become a major burden to healthcare systems and societies worldwide.1 In Japan, there are ∼9.5 million people with diabetes and 109 000 persons per year are diagnosed with diabetes.2 Additionally, 552 million people worldwide will have type 2 diabetes by the year 2030.3 The incidence of type 2 diabetes from pre-diabetes (impaired fasting glucose (IFG) and/or impaired glucose tolerance (IGT)) is about 10% (5.8–13.2%) per year.4–7 While diabetes is an irreversible state, pre-diabetes can be reverted to a normal glucose state. Therefore, many clinical trials have aimed to reduce the incidence of type 2 diabetes by targeting individuals with pre-diabetes.

Active vitamin D is currently prescribed as the drug of choice for osteoporosis and hypocalcaemia, but it has been reported that vitamin D and active vitamin D might have additional metabolic effects on tissues other than bone and calcium metabolism8–10 because vitamin D receptors have been found in various tissues, such as the brain, pancreas, breast, kidney, colon, prostate and immune cells.11–14 One of the additional effects of vitamin D is expected on the glucose metabolism. Vitamin D is regarded to have two mechanisms by which glucose metabolism in patients with glucose intolerance will be modulated, that is, a direct effect on pancreatic β-cells and an enhancing effect on insulin sensitivity in insulin-targeted organs. First, vitamin D receptors and 1-α-hydroxylase, which activates the synthesis of active vitamin D (1, 25(OH)2D3), are expressed in pancreatic β-cells.15 16 Therefore, it is reported that active vitamin D is involved in insulin biosynthesis.17–19 Second, in insulin-targeted organs, such as adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, the expression of the insulin receptor is enhanced by active vitamin D in cultured cells.20 Also, it is reported that vitamin D modulates the activation of Proxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor δ (PPARδ), which is one of the transcription factors controlling lipid metabolism in adipocytes and skeletal muscle.21

Many observational studies suggested that the serum 25-hydroxy vitamin D3 (25(OH)D3) level was inversely associated with the incidence of type 2 diabetes.22–26 Thus, some small-scale clinical trials have evaluated whether vitamin D and active vitamin D have the effect of improving insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, but the results are still controversial.27–33

With the aim of further addressing this issue, we designed a randomised controlled trial to evaluate whether active vitamin D, eldecalcitol, can prevent the incidence of type 2 diabetes among individuals with IGT and whether it can normalise blood glucose levels.

Objectives and end points

The objective of the present study is to elucidate the therapeutic effect of eldecalcitol (active vitamin D) on the prevention of type 2 diabetes among individuals with IGT. The primary end point is the HR of type 2 diabetes onset during 144 weeks of the study period. The secondary endpoint is the number of participants who achieve normoglycaemia at 48, 96 and 144 weeks.

Methods and analyses

Study design

This Diabetes Prevention with active Vitamin D (DPVD) study is designed as a prospective, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled and parallel group comparison study. In total, 750 adults with IGT will be randomly assigned to either the active vitamin D or control group, and treated until the onset of type 2 diabetes or the end of treatment period. This study is investigator-initiated and the study sponsor is the University of Occupational and Environmental Health.

Study population and settings

Participants will be recruited from outpatient clinics in Fukuoka prefecture and Kanagawa prefecture in Japan by the investigators. Individuals with IGT who meet all inclusion criteria and none of the exclusion criteria (table 1) will be enrolled for randomisation. All participants will be followed at the University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Kokura Medical Association Health Testing Center or Fujisawa City Hospital.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria for participation in the DPVD study

| Diagnostic criteria of IGT | FPG<126 mg/dL, 75 g OGTT's 2h-PG is 140≤2h-PG<200 mg/dL, and HbA1c<6.5% (<48 mmoL/moL). Additionally, he/she should not be medicated with any antidiabetic drug. |

| Inclusion criteria | Men and women aged≥30 years Individuals who are diagnosed with IGT Serum calcium (corrected value) <11.0 mg/dL |

| Exclusion criteria | Individuals who have participated in other clinical trials. Individuals who have been treated with active vitamin D, vitamin D supplement and/or calcium preparation during the past 3 months. Individuals who have already been diagnosed with type 1 or 2 diabetes. Individuals who have already been initiated with drug treatment for pre-diabetes. Individuals who are pregnant or have severe diseases, such as renal insufficiency (serum creatinine >1.5 mg/dL), hepatic insufficiency, psychosis, collagen disease, heart diseases, cerebrovascular diseases. A subinvestigator decides which participants’ conditions are inappropriate and precludes his/her participation in the study. |

2h-PG, 2-hour plasma glucose; DPVD, Diabetes Prevention with active Vitamin D; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; IGT, impaired glucose tolerance; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Registration procedure

After confirming that an individual conforms to the inclusion and not the exclusion criteria, a subinvestigator will obtain written informed consent from him/her. The subinvestigator will fill out the participants' recognition code list with the date of acquisition of the informed consent, the participant registration number (PRN) and personal information necessary for identifying the PRN with the participant. The PRN is composed of the name of the institution, sex (male (M) or female (F)), age (30–54 years (Y); ≥55 years (E)), 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) 2-hour plasma glucose (2h-PG; <170 mg/dL (L); ≥170 mg/dL(H)), and the number of visits. For example, in a hospital, a male participant, aged 43 years, with 176 mg/dL of 2h-PG, who is the fifth participant recruited in this study, will have a PRN composed of hospital name and MYH5. The subinvestigator will also fill out a case report form (CRF) with predetermined requirements and applies for registration and treatment assignment by sending the CRF with the PRN via fax to the Assignment Center at Kokura Medical Association.

Randomisation and blinding

Participants will be assigned in a 1:1 ratio to either the active vitamin D group or the control group by using a central randomisation method. A randomisation list is made using a permuted block procedure by a responsible person in the Assignment Center prior to the first participant's entry, and the list is stratified by sex, age, 75 g OGTT 2h-PG, because these factors are considered to affect the incidence of diabetes. The assignment list will be kept in a safe in the Assignment Center until it is time to open the safe. The location of the key will not be disclosed to the investigators or subinvestigators. Therefore, both the study personnel and the participants will be blinded to which treatment group. The key will be retrieved only after the trial is finished and data are fixed, except in the case of interim analyses or emergencies.

Intervention

Active vitamin D group: participants will receive 0.75 µg of eldecalcitol daily for 144 weeks or until the incidence of diabetes. Eldecalcitol is an active vitamin D3, which is added with the hydroxypropoxy group to the position of 2β in calcitriol (1, 25(OH)2D3), leading to an enhanced calcium absorption from the intestine. Control group: participants will receive one capsule of placebo daily for 144 weeks or until the incidence of diabetes. Participants in both groups will be seen at 12-week intervals by their subinvestigators. A brief (5–10 min long) talk on appropriate calorie intake from diet (ideal body weight×25–30 kcal) and exercise will be given to each participant on the basis of the common sheet.

Additional treatment criteria

When a participant meets the criteria for additional treatment described below, additional treatment will be initiated. Subinvestigators will describe the date and reason for the additional treatment in the CRF.

If low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels exceed 160 mg/dL, participants in both groups will be treated with statins. The subinvestigator can prescribe their statin of choice.

If triglyceride levels exceed 220 mg/dL, participants in both groups will be treated with fibrates. The subinvestigator can prescribe their fibrate of choice.

If bone mineral density (BMD) decreases to ≤−2.5 SD, participants in both groups will be treated with bisphosphonates. The subinvestigator can prescribe their bisphosphonate of choice. However, if there is a significant difference between the two groups in the number of participants with bisphosphonates administration, the analysis is to be performed after adjustment.

If systolic blood pressure exceeds 150 mm Hg and/or diastolic pressure exceeds 100 mm Hg, participants in both groups will be dosed with antihypertensive drugs. The subinvestigator can prescribe their hypertensive drug of choice.

Discontinuation of treatment

When a participant meets the discontinuation criteria described below, subinvestigators shall stop the intervention. They shall describe the date and reason for the discontinuation on the CRF, and perform the same examinations initially planned to be done after the 144-week treatment to evaluate the efficacy and safety. If the treatment discontinuation is caused by adverse events, subinvestigators will have to follow the participant until he/she recovers to the original state as much as possible.

A participant withdraws consent for participation.

Continuation of the study treatment has become difficult because of adverse events.

A participant is diagnosed with type 2 diabetes.

It is recognised that a participant did not satisfy eligibility criteria after registration, except for the restoration to normoglycaemia after treatment.

Serum calcium levels reach ≥11.0 mg/dL.

Subinvestigators judge that it is suitable to discontinue the study.

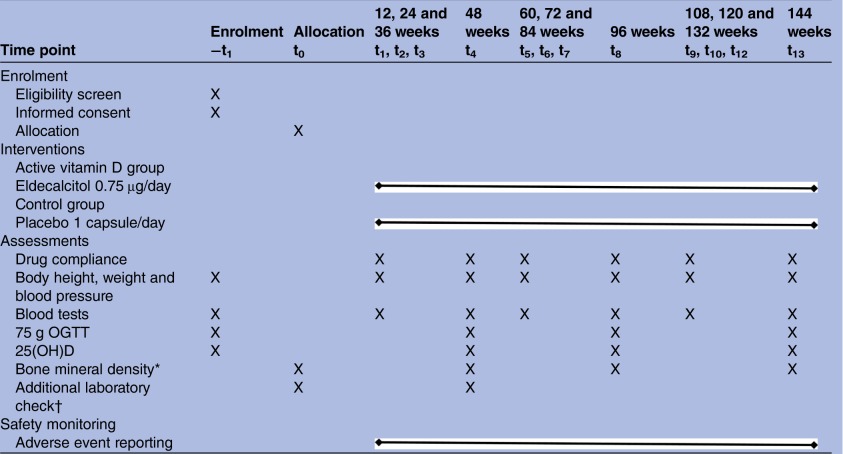

Outline of the study schedule

After registration and assignment to treatments, all participants will be seen at 12-week intervals by their subinvestigators (table 2). Body height, body weight and blood pressure will be measured, and blood samples will be taken at baseline and every 12 weeks thereafter. A list of blood tests is shown in table 3. A 75 g OGTT will be performed at baseline and annually. Serum 25(OH)D levels will be measured by using a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) system34 at baseline and annually. The system consists of ACQUITY UPLC I-Class and Xevo TQ-S (Waters, Milford, MA). BMD is not an obligatory measurement but will be evaluated on request from participants. If fasting plasma glucose (FPG) ≥126 mg/dL or glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥6.5% (≥48 mmoL/moL) is identified, a 75 g OGTT will be performed within 4 weeks. When HbA1c≥6.5% (≥48 mmoL/moL) and at least one of the following is recognised, the participant will be diagnosed with diabetes: FPG≥126 mg/dL, 75 g OGTT 2h-PG≥200 mg/dL, or casual plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dL.35 Participants with diabetes will be excluded from the followed-up data analysis. Conversely, when the participants achieve normoglycaemia, defined as meeting all three glycaemic criteria (FPG<110 mg/dL, 2h-PG<140 mg/dL, and HbA1c<6.5% (<48 mmoL/moL)) or both FPG<100 mg/dL and HbA1c<5.7% (<42 mmoL/moL)36 are recorded successively at least twice, the date will be recorded, and they will be followed up as analysis subjects until diabetes onset. The follow-up period for all participants is 144 weeks.

Table 2.

Outline of the study schedule

|

*Bone mineral density is measured by using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry at baseline and every 48 weeks if a participant wishes.

†Additional laboratory check includes serum levels of RANKL, osteoprotegerin, osteocalcin and leptin.

25(OH)D, 25-hydroxy vitamin D; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; RANKL, receptor activator of the nuclear factor κ-B ligand.

Table 3.

Blood tests

| Sampling period | Analysis |

|---|---|

| Baseline and every 12 weeks | Fasting plasma glucose or casual plasma glucose, HbA1c, IRI (glucose tolerance) White cell count, red blood cell, haematocrit, haemoglobin, platelet (blood counting) Natrium, potassium, chlorine, calcium, phosphorus, magnesium (serum electrolytes) LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides (lipids) AST, ALT, γ-GTP, proteins, albumin (liver function) Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, uric acid (renal function) |

| Baseline and every 48 weeks | 75-g OGTT includes IRI (glucose tolerance) 25(OH)D (vitamin D level) |

| Baseline and at 48-week | RANKL, osteoprotegerin, osteocalcin, leptin (additional laboratory check) |

25(OH)D, 25-hydroxy vitamin D; γ-GTP, γ-glutamyl-transpeptidase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IRI, immunoreactive insulin; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; RANKL, receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand.

Primary end point

The primary end point is the HR of type 2 diabetes onset during 144 weeks of the study period: active vitamin D group versus control group. We consider that the comparison of the treatment effect on type 2 diabetes onset between the two groups is the best measurement to evaluate the improvement of insulin resistance and glucose tolerance.

Secondary end points

1. The number of participants who achieve normoglycaemia at 48, 96 and 144 weeks.

2. HRs and 95% CIs of type 2 diabetes onset in each subgroup at baseline: age (≥/<65 years), sex (men/women), presence or absence of hypertension (systolic ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic ≥90 mm Hg), dyslipidaemia (LDL cholesterol ≥140 g/dL and/or triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL), obesity (body mass index ≥/<25 kg/m2), family history of diabetes, FPG (≥/<110 mg/dL), 2h-PG (≥/<170 mg/dL), 25(OH)D3 (≥/<25 ng/mL), homoeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-R) (∼1.6/1.61–2.49/2.5∼), and insulinogenic index (≥/<0.4).

3. HRs and 95% CI of type 2 diabetes development after adjusting for confounding factors: age (≥/<65 years), sex (men/women), presence or absence of hypertension (systolic ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic ≥90 mm Hg), dyslipidaemia (LDL cholesterol ≥140 g/dL and/or triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL), obesity (body mass index ≥/<25 kg/m2), family history of diabetes, FPG (≥/<110 mg/dL), 2h-PG (≥/<170 mg/dL), 25(OH)D3 (≥/<25 ng/mL), HOMA-R (≥/<2.5), insulinogenic index (≥/<0.4).

4. HRs of the incidence of adverse events.

5. Amount and percentage change in HOMA-R during the 144 weeks.

6. Changes in serum levels of the receptor activator of the nuclear factor κ-B ligand (RANKL), osteoprotegerin, osteocalcin and leptin during 48 weeks and the association of these items with insulin resistance (HOMA-R and quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI)).

Statistical analyses

The intention-to-treat population comprises all participants who undergo randomisation and receive at least one dose of the study drug, and will be analysed for the assessment of effectiveness and safety. In this analysis plan, the data set is called the full analysis set. The per protocol set comprises all participants who undergo randomisation and have no violation of inclusion and exclusion criteria, and this set will be analysed as the secondary population in the sensitivity analysis. When summating data in each specified period, those data that are obtained beyond an acceptable range of the prescribed observation date or obtained by other than the default method or condition will be treated as missing data. Basic statistics (mean, SD) are calculated for all continuous variables in each treatment arm and each visiting time. If necessary, basic statistics are calculated as a whole. As to FPG, HbA1c and other laboratory data, differences between the values at baseline and those taken every 12 weeks, and their per cent changes from baseline are calculated. Basic statistics, SEs or 95% CI are also calculated in these items. The distribution will be summarised in contingency tables for each treatment arm and each visiting time for all categorical variables. All significance tests and CI were two-sided and performed or constructed at the 5% significance level.

Sample size

Sample size was calculated with an 80% power (1-β), a 0.05 α error and a two-sided test for Log-rank test in Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. On the basis of our preliminary study (unpublished), we assumed that the cumulative incidence of type 2 diabetes in the control group is 23.14% (8.4% annually) and that in the active vitamin D group it is 14.81% (5.2% annually) during 3 years. Thus, the relative risk reduction and dropout ratio are assumed at 36% and 7%, respectively. As a result, 375 participants are required in each group (total 750).

Interim analyses

According to the incidence of diabetes, it is assumed that at least 133 participants will develop diabetes during the study period. The total number of interim analyses will be two. When 1 year has passed after the registration of the last participant, the first interim analysis will be conducted. Simultaneously, the dropout ratio of participants will be confirmed. If it is more than 3% per year, recruitment of trial participants will be conducted again. The second interim analysis will be done when 80 participants develop diabetes, that is, 60% of the expected diabetes incidence. Regarding the primary end point, when the difference, determined by the O'Brien-Fleming method, between the two groups is <0.0005 (in the first interim analysis), <0.014 (in the second interim analysis), or <0.045 (this is not an interim analysis but the final analysis),37 early completion of the trial will be decided by the independent Data Monitoring Committee.

Trial management and independent committees

The Trial Steering Committee (Chair: GS) will meet on a termly basis to review the status of the overall programme, including trial progress. In the case that they amend the protocol for a legitimate reason, they shall submit a report about the amendment to the principal investigator and Institutional Review Board as soon as possible for their review and approval. The decision of the amendment must be informed to all authorised study personnel immediately.

The data collection centre will collect the accumulating outcome data from all trial participating institutions. The staff member of the centre will clean up and aggregate the data but will not know the group to which a participant belongs.

The independent Data Monitoring Committee (Chair: TI) will audit the conduct of the trial with safety and ethics review regularly and conduct the interim analyses. When the trial is finished or the independent Data Monitoring Committee adjudicates the trial completion according to the result of the interim analyses, the final data set will be directly sent to a fully independent Data Analyses Committee (Chair: SM). The data will be analysed for all end points. Any investigators other than the Data Analyses Committee cannot access the data.

Ethical considerations and dissemination

This study is being conducted according to Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and the Declaration of Helsinki.38 It is carried out under the surveillance and guidance of the independent Data Monitoring Committee in compliance with the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH)-GCP guidelines. A written informed consent is obtained from each participant before study participation. Participants are informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. This study was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network clinical trials registry (UMIN000010758). The study results will be presented at national and international conferences, and submitted for publication in peer-reviewed journals.

Discussion

There is increasing interest in the potential health benefits by taking vitamin D supplements or active vitamin D formulations. Recent research suggests that vitamin D deficiency may cause both bone diseases and a range of non-skeletal diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases, cancers (eg, colorectal, breast), type 2 diabetes, infectious diseases (eg, influenza, common cold, tuberculosis) and autoimmune diseases (eg, multiple sclerosis, type 1 diabetes).9 39 However, most of these data come from observational studies, and clinical trial data on the effects of vitamin D are scarce and inconsistent.31–33 Hence, we focused on the effectiveness of eldecalcitol, active vitamin D, on the incidence of type 2 diabetes among individuals at high risk for diabetes and designed the protocol of the DPVD study. This study will provide valuable information, both on the incidence of type 2 diabetes and the improvement to the normal glucose state from IGT.

As a result of necessary compromises in study design, the DPVD study protocol has a number of strengths and weaknesses. Since this study consists of only Japanese participants, it is unknown whether the results of this study are adapted to other ethnicities. Several large-scale clinical trials to examine the benefits of vitamin D in a number of chronic diseases have recently been started around the world: USA, Finland, New Zealand, eight European cities and the UK.39 40 The primary end points are cancer, cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, infection, hypertension, bone fracture, cognitive function and longevity. However, there is no trial of which primary end point is diabetes. As compared with these trials in which the number of participants is 2000–20 000, that in our study is 750. However, our study is not considered to be inferior to others because of the following reasons. In other trials, primary end points are diverse: study participants are almost healthy persons; there is no regular outpatient follow-up by a physician; vitamin D supplements are delivered by mail once a year, whereas in our study there is one primary end point: study participants are at high risk for diabetes; all participants visit clinics to be followed by physicians every 3 months; they are prescribed active vitamin D formulations at that visit. Therefore, the drug compliance and the follow-up ratio in our study will be better than those in other trials; additionally, the sample size of our study, 750 participants, will be enough to evaluate the primary end point.

Although vitamin D supplements are chosen to be used in most of the other trials, active vitamin D formulation is chosen in our study. Humans get vitamin D from exposure to sunlight, from their diet and from dietary supplements. Vitamin D from skin and diet is metabolised in the liver to 25-hydroxyvitamin D; 25-hydroxyvitamin D is metabolised in the kidneys by the enzyme 25-hydroxyvitamin D-1α-hydroxylase to its active form, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Vitamin D itself does not have a physiological effect but 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D does—it promotes intestinal calcium absorption in the small intestine and calcium resorption from bone by interacting with the vitamin D receptor to enhance the expression of the epithelial calcium channel and calcium-binding protein.11 As a result, the administration of active vitamin D rather than vitamin D leads to expression of these physiological effects more effectively and promptly both on bone and calcium metabolism and on non-skeletal tissue and glucose metabolism. Hence, we chose active vitamin D formulation in this study. In conclusion, results from this study will provide a clearer picture of the risk and benefits of eldecalcitol (active vitamin D) for prevention of type 2 diabetes, and contribute to the resolution of a debate ‘whether vitamin D and active vitamin D is panacea for glucose metabolism’.41

Current study status

The DPVD study began recruiting participants in June 2013 and we are still collecting data. It is expected to be reported in 2017.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all study participants and all staff of this study for recruiting the participants and contributing to the accurate recording of trial data.

Footnotes

Contributors: TK, GS, SM and FK conceived and designed the study. TK drafted the protocol of the study and organised the study implementation. TK, GS, TI, SM, FK, YO and YT refined the study protocol and study implementation. SM and FK conducted the statistical analyses. TK, GS, TI, SM and YT have drafted the manuscript. All the authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This study received an unrestricted grant from Kitakyushu Medical Association, and was supported by Chugai Pharmaceutical and Taisho-Toyama Pharmaceutical.

Disclaimer: The funders were not involved in the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of the study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol has been approved by the Institutional Review Board at Kokura Medical Association, University of Occupational and Environmental Health and Fujisawa City Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional data can be requested via email to the corresponding author, but the decision to disseminate the data would be solely based on the author's discretion.

References

- 1.Herman WH. The economics of diabetes prevention. Med Clin North Am 2011;95:373–84, viii 10.1016/j.mcna.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Summary of results. National Health and Nutrition Survey Report 2012. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/bunya/kenkou/eiyou/h24-houkoku.html.

- 3.International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes Atlas, 6th edn Basel: International Diabetes Federation, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J, Eriksson JG et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1343–50. 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393–403. 10.1056/NEJMoa012512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawahara T, Takahashi K, Inazu T et al. Reduced progression to type 2 diabetes from impaired glucose tolerance after a 2-day in-hospital diabetes educational program: the Joetsu Diabetes Prevention Trial. Diabetes Care 2008;31:1949–54. 10.2337/dc07-2272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kawamori R, Tajima N, Iwamoto Y et al. Voglibose for prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomised, double-blind trial in Japanese individuals with impaired glucose tolerance. Lancet 2009;373:1607–14. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60222-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kienreich K, Grubler M, Tomaschitz A et al. Vitamin D, arterial hypertension & cerebrovascular disease. Indian J Med Res 2013;137:669–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pludowski P, Holick MF, Pilz S et al. Vitamin D effects on musculoskeletal health, immunity, autoimmunity, cardiovascular disease, cancer, fertility, pregnancy, dementia and mortality-a review of recent evidence. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:976–89. 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rejnmark L, Avenell A, Masud T et al. Vitamin D with calcium reduces mortality: patient level pooled analysis of 70,528 patients from eight major vitamin D trials. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97:2670–81. 10.1210/jc.2011-3328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 2007;357:266–81. 10.1056/NEJMra070553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB et al. The role of vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2007;92:2017–29. 10.1210/jc.2007-0298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kendrick J, Targher G, Smits G et al. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D deficiency is independently associated with cardiovascular disease in the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Atherosclerosis 2009;205:255–60. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.10.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dusso AS, Brown AJ, Slatopolsky E. Vitamin D. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2005;289:F8–28. 10.1152/ajprenal.00336.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JA, Grande JP, Roche PC et al. Immunohistochemical localization of the 1,25(OH)2D3 receptor and calbindin D28k in human and rat pancreas. Am J Physiol 1994;267:E356–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bland R, Markovic D, Hills CE et al. Expression of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3-1alpha-hydroxylase in pancreatic islets. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2004;89–90:121–5. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bourlon PM, Billaudel B, Faure-Dussert A. Influence of vitamin D3 deficiency and 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 on de novo insulin biosynthesis in the islets of the rat endocrine pancreas. J Endocrinol 1999;160:87–95. 10.1677/joe.0.1600087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maestro B, Dávila N, Carranza MC et al. Identification of a Vitamin D response element in the human insulin receptor gene promoter. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2003;84:223–30. 10.1016/S0960-0760(03)00032-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeitz U, Weber K, Soegiarto DW et al. Impaired insulin secretory capacity in mice lacking a functional vitamin D receptor. FASEB J 2003;17:509–11. 10.1096/fj.02-0424fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunlop TW, Väisänen S, Frank C et al. The human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta gene is a primary target of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and its nuclear receptor. J Mol Biol 2005;349:248–60. 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.03.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luquet S, Gaudel C, Holst D et al. Roles of PPAR delta in lipid absorption and metabolism: a new target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta 2005;1740:313–17. 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas GN, Scragg R, Jiang CQ et al. Hyperglycaemia and vitamin D: a systematic overview. Curr Diabetes Rev 2012;8:18–31. 10.2174/157339912798829223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muscogiuri G, Sorice GP, Ajjan R et al. Can vitamin D deficiency cause diabetes and cardiovascular diseases? Present evidence and future perspectives. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2012;22:81–7. 10.1016/j.numecd.2011.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holick MF. Diabetes and the vitamin d connection. Curr Diab Rep 2008;8:393–8. 10.1007/s11892-008-0068-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forouhi NG, Ye Z, Rickard AP et al. Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and the risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC)-Norfolk cohort and updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetologia 2012;55:2173–82. 10.1007/s00125-012-2544-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pittas AG, Nelson J, Mitri J et al. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D and progression to diabetes in patients at risk for diabetes: an ancillary analysis in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care 2012;35:565–73. 10.2337/dc11-1795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu S, Song Y, Ford ES et al. Dietary calcium, vitamin D, and the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older U.S. women. Diabetes Care 2005;28:2926–32. 10.2337/diacare.28.12.2926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pittas AG, Dawson-Hughes B, Li T et al. Vitamin D and calcium intake in relation to type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care 2006;29:650–6. 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitri J, Dawson-Hughes B, Hu FB et al. Effects of vitamin D and calcium supplementation on pancreatic β cell function, insulin sensitivity, and glycemia in adults at high risk of diabetes: the Calcium and Vitamin D for Diabetes Mellitus (CaDDM) randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2011;94:486–94. 10.3945/ajcn.111.011684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eftekhari MH, Akbarzadeh M, Dabbaghmanesh MH et al. Impact of treatment with oral calcitriol on glucose indices in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2011;20:521–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pilz S, Kienreich K, Rutters F et al. Role of vitamin D in the development of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 2013;13:261–70. 10.1007/s11892-012-0358-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Autier P, Boniol M, Pizot C et al. Vitamin D status and ill health: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014;2:76–89. 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70165-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.George PS, Pearson ER, Witham MD. Effect of vitamin D supplementation on glycaemic control and insulin resistance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2012;29:e142–50. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03672.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saenger AK, Laha TJ, Bremner DE et al. Quantification of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D(2) and D(3) using HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry and examination of reference intervals for diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;125:914–20. 10.1309/J32U-F7GT-QPWN-25AP [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seino Y, Nanjo K, Tajima N et al. Report of the Committee on the classification and diagnostic criteria of diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig 2010;1:212–28. 10.1111/j.2040-1124.2010.00074.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2010;33(Suppl 1):S62–9. 10.2337/dc10-S062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulz KF, Grimes DA. Multiplicity in randomised trials II: subgroup and interim analyses. Lancet 2005;365:1657–61. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66516-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Recommendations guiding physicians in biomedical research involving human subjects. JAMA 1997;277:925–6. 10.1001/jama.1997.03540350075038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kupferschmidt K. Uncertain verdict as vitamin D goes on trial. Science 2012;337:1476–8. 10.1126/science.337.6101.1476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pilz S, Rutters F, Dekker JM. Disease prevention: vitamin D trials. Science 2012;338:883 10.1126/science.338.6109.883-c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Osei K. 25-OH vitamin D: is it the universal panacea for metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:4220–2. 10.1210/jc.2010-1550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]