Abstract

Objectives

To determine the incidence of adverse drug events (ADEs) and assess their severity and preventability in four Saudi hospitals.

Design

Prospective cohort study.

Setting

The study included patients admitted to medical, surgical and intensive care units (ICUs) of four hospitals in Saudi Arabia. These hospitals include a 900-bed tertiary teaching hospital, a 400-bed private hospital, a 1400-bed large government hospital and a 350-bed small government hospital.

Participants

All patients (≥12 years) admitted to the study units over 4 months.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Incidents were collected by pharmacists and reviewed by independent clinicians. Reviewers classified the identified incidents as ADEs, potential ADEs (PADEs) or medication errors and then determined their severity and preventability.

Results

We followed 4041 patients from admission to discharge. Of these, 3985 patients had complete data for analysis. The mean±SD age of patients in the analysed cohort was 43.4±19.0 years. A total of 1676 ADEs were identified by pharmacists during the medical chart review. Clinician reviewers accepted 1531 (91.4%) of the incidents identified by the pharmacists (245 ADEs, 677 PADEs and 609 medication errors with low risk of causing harm). The incidence of ADEs was 6.1 (95% CI 5.4 to 6.9) per 100 admissions and 7.9 (95% CI 6.9 to 8.9) per 1000 patient-days. The occurrence of ADEs was most common in ICUs (149 (60.8%)) followed by medical (67 (27.3%)) and surgical (29 (11.8%)) units. In terms of severity, 129 (52.7%) of the ADEs were significant, 91 (37.1%) were serious, 22 (9%) were life-threatening and three (1.2%) were fatal.

Conclusions

We found that ADEs were common in Saudi hospitals, especially in ICUs, causing significant morbidity and mortality. Future studies should focus on investigating the root causes of ADEs at the prescribing stage, and development and testing of interventions to minimise harm from medications.

Keywords: Adverse Drug Events (ADEs), prospective cohort study, Saudi Arabia

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is one of the largest investigating the incidence of adverse drug events (ADEs) in the Middle East.

This study is limited by a lack of hospitals from small towns and rural areas, and these settings may have an even higher incidence of ADEs.

Our study findings are not generalisable to overall Saudi Arabia because the study was conducted in Riyadh only.

Introduction

adverse drug events (ades) are a major cause of morbidity, mortality and increased healthcare costs and hospitalisation.1–3 an ADE is defined as an injury caused by a medication.4 they are largely preventable and occur mostly at the prescribing stage of the medication use process.2 4 5 The incidence of ADEs reported in the literature varies significantly between countries, largely because of the differences in available drug products, practices, training, study methodology and patient safety initiatives among countries. Early in 1995, Bates et al2 reported an incidence of 6.5 per 100 admissions in the USA; however, using the same methods, a study in Japan reported an incidence of 17 per 100 admissions,4 suggesting real differences between these two countries. In Saudi Arabia, a single hospital study reported an incidence of 8.5 per 100 admissions,5 and a cross-sectional study in Morocco reported an incidence of 4.2 per 100 admissions.6 A recent international study using hospital datasets estimated the prevalence of ADEs to be 3.2% in England, 4.8% in Germany and 5.6% in the USA.7 It is important to mention that the incidence of preventable ADEs was estimated by a population-based study to be 13.8 per 1000 person-years.8

Despite the evidence that ades are common and could be life-threatening, little attempt has been made in Saudi Arabia to detect and estimate the incidence of ADEs in hospitalised patients. Such a paucity of research hinders the development of prevention strategies to improve patient safety. To date, one prospective chart review study has been conducted in a single teaching hospital in the Saudi setting.5 therefore we sought to estimate incident ADEs in a larger patient sample from different hospitals with diverse settings and varying practices and strategies for managing patients. Therefore, the objective of our study was to estimate the incidence and risk factors associated with ades in Saudi hospitals and determine their severity and preventability.

Methods

Study design and setting

The ades in Saudi Arabia (ADESA) project was a 4-month prospective cohort study involving four hospitals with diverse settings. These hospitals included a 900-bed tertiary teaching hospital, a 400-bed private hospital, a 1400-bed large government hospital and a 350-bed small government hospital. We randomly selected medical, surgical and intensive care units (ICUs) from these hospitals and excluded obstetrics and paediatric units because of the lower frequency of use of medications within these units. We included patients older than 12 years of age admitted for more than 24 hours during the 4-month study period. None of the hospitals had electronic medical records or decision support systems. Instead, hospitals used paper-based systems where physician notes (including prescribed medications) and nursing notes (including daily administered medications) were handwritten and kept in patient charts. Medication orders were sent to the inpatient pharmacies and dispensed using unit dose systems.

Definitions

Each incident was defined as an ADE (preventable and non-preventable), potential ADE (PADE) (which was classified as either intercepted or non-intercepted), or a medication error with low risk of causing harm. We defined ADE as any injury resulting from medical interventions related to a drug and includes both adverse drug reaction (ADR) in which no error occurred and complications resulting from medication errors.2 9 10 Non-preventable ADEs, also known as ADRs, are defined by the WHO as ‘a response to a drug which is noxious and unintended, and which occurs at doses used in man for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiological function’.11 A non-preventable ADE is an injury with no error in the medication process. An example of this would be an allergic reaction in a patient not previously known to be allergic to that particular medication. Preventable ADEs were those that result from medication errors at any stage of the medication use process.2 An example of this would be an anaphylactic reaction to an antibiotic that the patient is known to be allergic to. Preventability was further classified into definitely preventable/non-preventable and probably preventable/non-preventable. A PADE was an error that carries a risk of causing injury related to the use of a medication but harm did not occur, either because of specific circumstances or because the error was intercepted.9 Intercepted PADEs were those that had the potential to cause injury but did not reach the patient because they were intercepted by someone during the medication use process. Non-intercepted PADEs were those with the potential to cause harm but failed to do so after the medication reached the patient.9 Medication errors with a low risk of causing harm included those with minimal risk to cause ADEs or PADEs. Comorbidities were determined using Charlson's Comorbidity Index, which is a method of classifying comorbidities of patients according to the International Classification of Disease (ICD). Each comorbidity class has an associated weight of 1, 2, 3 or 6. The sum of all weights results in a single comorbidity score for each patient, with higher scores predictive of adverse outcomes such as mortality or high resource use.

Data collection and classification of incidents

Data were collected as described in detail elsewhere.5 Briefly, trained clinical pharmacists collected data each day during the study period. In addition, all nurses working in the particular units were invited to attend monthly in-service presentations on the study to increase their awareness about ADE reporting. The pharmacists reviewed patients' medical charts of all admitted patients in each of the participating units to report demographic characteristics of patients, comorbidity, and the number of medications. When incidents were noted, the pharmacists wrote a detailed description of each incident and captured the relevant patient characteristics and event history.

Two independent clinicians who were not involved in the data collection process were provided with a study manual that contained study terminology and a guide on the assessment of the severity and preventability of an incident. The manual included examples of incidents and their severity classifications. The severity of the incidents was categorised as significant, serious, life-threatening or fatal using a methodology developed by the Brigham and Women's Hospital's Center for Patient Safety Research and Practice.2 The study manual served as a guide for the reviewers to independently review the incidents and decide on inclusion of incidents and further classify them as ADEs, PADEs or medication errors with low risk of causing harm. They were then able to assess severity and preventability. Preventability categories were defined as follows: definitely preventable, probably preventable, definitely not preventable or probably not preventable.2 In the event of disagreement on the classification of the incidents, the clinicians called for a meeting to decide whether to include or exclude the incidents. The primary outcomes of this study were incidence of ADEs, PADEs and medication errors with low risk of causing harm, as defined previously. The secondary outcomes were the severity of events, their preventability, and associated risk factors. The research and ethics committees of the four hospitals approved this study.

Data analysis

We calculated the overall incidence per 100 admissions and crude rate per 1000 patient-days with 95% CIs. In addition, the incidence was calculated by hospital and by unit type. Continuous variables are presented as mean±SD and categorical variables as number and percentage. Inter-rater reliability was assessed using the κ statistic for assessment of the presence of an ADE and its preventability and severity. To evaluate the univariate association of potential risk factors with ADEs, we used univariate logistic regression. The variables included in the univariate analysis were age, gender, Charlson's Comorbidity Index weight, length of hospital stay, number of medications, and service type. Variables found to be statistically significant (p<0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression final model. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software V.22.0.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the patients

Clinical pharmacists reviewed the medical charts of 4041 patients. Complete data for 3985 patients were analysed (table 1). The total length of hospital stay for patients was 30 996 days. The study was conducted in four hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (977 patients from a teaching hospital, 2033 patients from a private hospital, 683 patients from a large government hospital, and 292 patients from a small government hospital). There was a slight majority of male patients (52.7%) (table 1). The patients were admitted to one of the three services (medical, 1352; surgery, 1771; ICU, 862). The mean length of hospital stay was 8.1±10.2 days and the mean age of the patients was 43.4±19.0 years (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 3985 patients admitted to four hospitals in Riyadh

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) | Mean±SD |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 2102 (52.7) | – |

| Female | 1883 (47.3) | – |

| Hospital type | ||

| Hospital 1 (teaching hospital) | 977 (24.5) | – |

| Hospital 2 (private hospital) | 2033 (51.1) | – |

| Hospital 3 (large government hospital) | 683 (17.1) | – |

| Hospital 4 (small government hospital) | 292 (7.3) | – |

| Service | ||

| Medicine | 1352 (33.9) | – |

| Surgery | 1771 (44.5) | – |

| Intensive care unit | 862 (21.6) | – |

| Age, years | – | 43.4±19.0 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | – | 8.1±10.2 |

| Comorbidities (Charlson's Index weight) | – | 1.1±1.4 |

| Number of medications | – | 2.5±2.9 |

Incidents review and classification

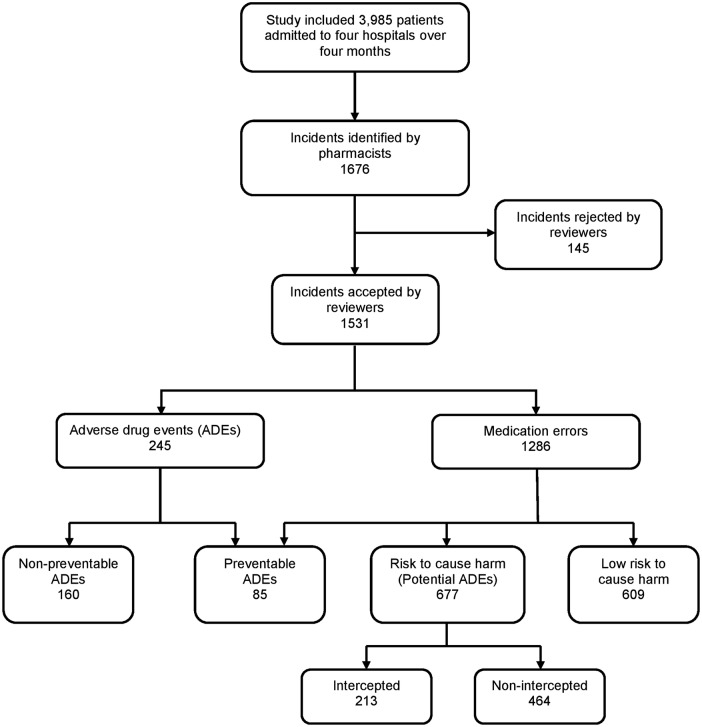

The pharmacists' chart reviews in the four hospitals identified 1676 cases of ADEs, PADEs and medication errors. Physicians reviewed and accepted 1531 (91.3%) of the cases, which were classified as 609 (39.8%) medication errors with low risk of harm, 677 (44.2%) PADEs, and 245 (16%) ADEs (figure 1). Among the ADEs, 85 (34.7%) were deemed preventable and 160 (65.3%) were judged to be non-preventable (table 2). The majority of the preventable ADEs occurred at the prescribing stage (75; 88.2%) followed by the administering stage (7; 8.2%), dispensing stage (2; 2.4%) and monitoring stage (1; 1.2%). Over half (129 (52.7%)) of the ADEs were significant, 91 (37.1%) were serious, 22 (9%) were life-threatening, and 3 (1.2%) were fatal. Of the 85 preventable ADEs, 36 (42.4%) were significant, 38 (44.7%) were serious, 10 (11.9%) were life-threatening and 1 (1.2%) was fatal. Among PADEs, 213 (31.9%) were intercepted by the medical staff. Regarding severity of PADEs, 383 (56.6%) were significant, 271 (40%) were serious and 23 (3.4%) were life-threatening.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 2.

Overall incidence of adverse drug events (ADEs), potential ADEs (PADEs) and medication errors with low risk of causing harm

| Number of incidents (N=1531) | Per cent | Incidence per 100 admissions (95% CI) | Crude rate per 1000 patient-days (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication errors with low risk of causing harm | 609 | 39.8 | 15.3 (14.1 to 16.5) | 19.6 (18.7 to 21.2) |

| PADEs | 677 | 44.2 | 16.9 (15.7 to 18.3) | 21.8 (20.2 to 23.5) |

| Intercepted PADEs (n=213) | 5.3 (4.6 to 6.1) | 6.8 (5.9 to 7.8) | ||

| Not intercepted PADEs (n=464) | 11.6 (10.6 to 12.7) | 14.9 (13.6 to 16.3) | ||

| ADEs (harm) | 245 | 16 | 6.1 (5.4 to 6.9) | 7.9 (6.9 to 8.9) |

| Preventable ADEs (n=85) | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.6) | 2.7 (2.2 to 3.3) | ||

| Non-preventable ADEs (n=160) | 4.0 (3.4 to 4.6) | 5.1 (4.4 to 6.0) |

Medication errors with low risk of causing harm include those with low risk of causing ADEs or PADEs.

Overall incidence of ADEs and medication errors with low risk of causing harm

The incidence of ADEs per 100 admissions was 6.1 (95% CI 5.4 to 6.9) and the incidence of PADEs was 16.9 (95% CI 15.7 to 18.3) per 100 admissions (table 2). The incidence of medication errors with low risk of causing harm was 15.3 (95% CI 14.1 to 16.5) per 100 admissions, and the incidence of preventable ADEs was 2.1 (95% CI 1.7 to 2.6) per 100 admissions. The incidence of non-preventable ADEs was 4.0 (95% CI 3.4 to 4.6) per 100 admissions, and the incidence of intercepted PADEs was 5.3 (95% CI 4.6 to 6.1) per 100 admissions (table 2). Incidents of preventable ADEs, PADEs and medication errors with low risk of causing harm most commonly occurred at the prescribing stage (1288 (84.1%)), followed by the dispensing stage (69 (4.5%)) and the administering stage (43 (2.8%)). Table 3 shows the distribution of incidents among the four hospitals. Examples of PADEs at different stages of the medication use process are listed in online supplementary appendix A. The incidence of ADEs was highest in the large government hospital (16.6 (95% CI 13.5 to 20.2) per 1000 patient-days and 32.9 (95% CI 27.7 to 38.4) per 100 admissions) followed by the teaching hospital (8.7 (95% CI 6.9 to 10.6) per 1000 patient-days and 8.5 (95% CI 6.8 to 10.4) per 100 admissions) (table 3).

Table 3.

Classification of adverse drug events (ADEs) by hospital type

| Units | ADEs | Length of hospital stay (days) | ADE crude rate per 1000 patient-days (95% CI) | Number of admissions | ADE incidence per 100 admissions (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital 1 | 83 | 9585 | 8.7 (6.9 to 10.6) | 977 | 8.5 (6.8 to 10.4) |

| Hospital 2 | 53 | 9032 | 5.9 (4.4 to 7.6) | 2033 | 2.6 (2.1 to 3.3) |

| Hospital 3 | 13 | 6613 | 2.1 (1.1 to 3.2) | 683 | 2.1 (1.1 to 3.2) |

| Hospital 4 | 96 | 5766 | 16.6 (13.5 to 20.2) | 292 | 32.9 (27.7 to 38.4) |

Hospital 1, teaching hospital; Hospital 2, private hospital; Hospital 3, small government hospital; Hospital 4, large government hospital.

bmjopen-2015-010831supp_appendix.pdf (138.7KB, pdf)

The incidence of PADEs was predominantly higher in the private hospital (367; 23.9%). Medication errors were mostly seen in the private hospital (367; 23.9%).

Classification of ADE incidents by service type

The incidence of ADEs was highest in the ICUs at 13.7 (95% CI 11.6 to 16.1) per 1000 patients-days and 17.4 (95% CI 14.7 to 20.3) per 100 admissions, followed by the medical units at 6.1 (95% CI 4.7 to 7.7) per 1000 patients-days and 4.8 (95% CI 3.8 to 6.1) per 100 admissions (table 4).

Table 4.

Classification of incidence of adverse drug events (ADEs) by type of service

| Unit | ADEs | Patient-days, n | ADE crude rate per 1000 patient-days (95% CI) | Admissions, n | ADE incidence per 100 admissions (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | 66 | 10 767 | 6.1 (4.7 to 7.7) | 1352 | 4.8 (3.8 to 6.1) |

| Surgical | 29 | 9310 | 3.1 (2.1 to 4.4) | 1771 | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.3) |

| ICU | 150 | 10 919 | 13.7 (11.6 to 16.1) | 862 | 17.4 (14.7 to 20.3) |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Medication classes involved in ADEs, PADEs and medication errors with low risk of causing harm

Anticoagulants (21.6%) and antibiotics (20.8%) were the most common medication classes associated with ADEs. Medication classes most commonly associated with PADEs were antibiotics (31.3%) followed by anticoagulants (17.3%) and antihypertensives (9.3%) (table 5).

Table 5.

Medication classes involved in adverse drug events (ADEs), potential ADEs (PADEs) and medication errors with low risk of causing harm

| Medication class | ADEs, n (%) (N=245) | PADEs, n (%) (N=677) | Medication errors with low risk of causing harm, n (%) (N=609) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 51 (20.8) | 212 (31.3) | 193 (31.7) |

| Anticoagulants | 53 (21.6) | 117 (17.3) | 92 (15.1) |

| Antihypertensives | 49 (20) | 63 (9.3) | 61 (10) |

| NSAIDs | 11 (4.5) | 41 (6.1) | 55 (9) |

| GI medicines | 4 (1.6) | 43 (6.4) | 39 (6.4) |

| Antidiabetics | 5 (2) | 32 (4.7) | 26 (4.3) |

| Steroids | 14 (5.7) | 12 (1.8) | 17 (2.8) |

| Electrolytes | 7 (2.9) | 19 (2.8) | 6 (1) |

| Cardiovascular medicines | 4 (1.6) | 15 (2.2) | 11 (1.8) |

| Dyslipidaemic agents | 7 (2.9) | 16 (2.4) | 6 (1) |

| Analgesics | 4 (1.6) | 9 (1.3) | 15 (2.5) |

| Antiasthmatics | 5 (2) | 14 (2.1) | 6 (1) |

| Antituberculosis | 3 (1.2) | 11 (1.6) | 7 (1.1) |

| Vitamins | 0 | 8 (1.2) | 5 (0.8) |

| Antifungals | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.6) | 6 (1) |

| Antiseizures | 5 (2) | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) |

| Antipsychotics | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 6 (1) |

| Thyroid agents | 0 | 5 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) |

| Antivirals | 4 (1.6) | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| Antihistamines | 1 (0.5) | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) |

| Sedatives | 4 (1.6) | 1 (0.1) | 0 |

| Anticancers | 0 | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.3) |

| Others | 12 (4.9) | 41 (6.1) | 49 (8) |

GI, gastrointestinal; NSAID, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

Agreement of physicians’ reviews on the classification of the incidents

The κ value was 0.71 for the presence of ADEs, 0.67 for the presence of medication errors, and 0.62 for the presence of PADEs. The κ value for preventability of ADEs was 0.68 (definitely or probably preventable vs definitely or probably not preventable). For the severity of ADEs, the κ value was 0.74 (fatal vs significant, serious or life-threatening), 0.63 (life-threatening vs significant, serious or fatal), 0.52 (significant vs serious, life-threatening or fatal), and 0.48 (serious vs life-threatening or fatal) (table 6).

Table 6.

Inter-rater reliability of the incident type and their severity and preventability

| Severity | Agreement, % | κ value |

|---|---|---|

| Exclude vs ADEs, PADE or medication error | 56.4 | 0.63 |

| ADEs vs PADE, medication error or exclude | 93.6 | 0.71 |

| PADEs vs ADE, medication error or exclude | 70.9 | 0.62 |

| Medication error vs ADEs, PADE or exclude | 93.7 | 0.67 |

| Preventable vs non-preventable ADEs | 92.2 | 0.68 |

| Fatal vs life-threatening, serious or significant | 100 | 0.74 |

| Life-threatening vs fatal, serious or significant | 100 | 0.63 |

| Serious vs fatal, life-threatening or significant | 60.5 | 0.48 |

| Significant vs fatal, life-threatening or serious | 84.2 | 0.52 |

ADE, adverse drug event; PADE, potential ADE.

Factors associated with ADEs

Factors significantly associated with ADEs included age (OR 1.012; 95% CI 1.003 to 1.021), number of medications (OR 1.062; 95% CI 1.008 to 1.119), length of hospital stay (OR 1.025; 95% CI 1.015 to 1.035) and admission to ICUs (OR 3.276; 95% CI 2.005 to 5.354) and medical units (OR 1.736; 95% CI 1.078 to 2.796) (table 7). Gender was not significantly associated with ADEs (p=0.248); therefore, it was not included in the multivariate analysis.

Table 7.

Factors associated with adverse drug events

| 95% CI |

p Value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI |

p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor | Unadjusted OR | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||

| Age | 1.024 | 1.017 | 1.032 | <0.001 | 1.012 | 1.003 | 1.021 | 0.009 |

| Number of medications | 1.193 | 1.148 | 1.240 | <0.001 | 1.062 | 1.008 | 1.119 | 0.023 |

| Charlson's Comorbidity Index weight | 1.251 | 1.158 | 1.352 | <0.001 | 1.041 | 0.937 | 1.157 | 0.452 |

| Length of hospital stay | 1.042 | 1.034 | 1.051 | <0.001 | 1.025 | 1.015 | 1.035 | <0.001 |

| Gender (male)* | 0.848 | 0.642 | 1.121 | 0.248 | – | – | – | – |

| ICU† | 7.786 | 5.259 | 11.528 | <0.001 | 3.276 | 2.005 | 5.354 | <0.001 |

| Medical unit† | 2.539 | 1.664 | 3.872 | <0.001 | 1.736 | 1.078 | 2.796 | 0.023 |

*Reference category: female.

†Reference category: surgery.

ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

In this study we evaluated the incidence of ADEs and found that they were common, with one-third caused by medication errors judged to be preventable. Errors resulting from preventable ADEs were most common at the prescribing stage followed by the dispensing and administering stages. Most of the preventable ADEs were judged to be serious. The incidence of ADEs reported in our study is similar to that found in previous studies.2 5 However, a higher incidence was reported in Japan.4 The differences between our study results and the results from the Japanese study could be due to the longer hospital stay in Japan and differences in healthcare systems between the countries. The similarity between our findings and the US study may be due to the use of the same methods for data collection, ADE detection, and event classification and the similarities in the healthcare systems. The incidence at the prescribing stage in our study was higher than reported in Malaysia (25.15%),12 Indonesia (20.4%)13 and Thailand (1%).14

The κ values reported in our study range from substantial to moderate according to the measure of the strength of agreement suggested by Landis and Koch.15 The lowest level of agreement in the present study was reported for judgement regarding the severity of the incidents (0.48 and 0.52). However, a similar study reported κ values lower than those found in our study (0.32 and 0.37).2

We included 3985 patients and found 245 ADEs, of which 35% were judged to be preventable. Gurwitz et al8 identified 546 ADEs during 2403 nursing home residence admissions and reported that 51% of the observed ADEs were preventable. Bates et al2 determined the incidence of ADEs in 4031 patients and found 247 ADEs, of which 28% were deemed preventable. In 2009, Hug et al16 assessed the occurrence of ADEs in 1200 patients from six community hospitals and identified 180 ADEs, of which 75% were preventable. A multicentre cohort study of 3459 patients identified 1010 ADEs and found that 14% of the identified ADEs were preventable.4

Regarding PADEs, we noticed that only one-third of the events were intercepted. It is noteworthy to highlight that three of the four hospitals had clinical pharmacists monitoring patient treatments and most of the intercepted PADEs were in those hospitals.

Our study revealed that ADEs were associated with admission to ICUs and older age. Consistent with our results, other studies also reported that admission to ICUs4 17 and older age4 8 were major factors associated with ADEs. In support of this finding, perhaps special care should be given to older people who are admitted to ICUs because of the added risk of combining two risk factors.

Several important basic medication safety practices are not widely adopted in most Saudi hospitals.18 19 Therefore, there are opportunities for improving the safe use of medications and preventing ADEs in hospitals in Saudi Arabia. On a national level, the Saudi Food Drug Authority may lead efforts to prevent ADRs, and the Saudi Medication Safety Centre may lead initiatives to prevent medication errors. For example, the use of pharmacists to ascertain complete medication histories at admission and provide discharge counselling reduced the incidence of ADEs.20 21 Although reporting is a good tool to identify and prevent ADEs, under-reporting is a common challenge in Saudi hospitals.22

There is lack of literature about incident medication errors in South-East Asian23 and Middle Eastern countries.24 Future research could focus on investigating the causes of ADEs that occur during the medication use process, especially at the prescribing stage. More research is needed on the causes of ADEs using both qualitative and quantitative methodologies with the use of standard definitions of events and severity classification. Using methods similar to those used in this study, the benefits of interventions to prevent ADEs can be estimated and compared with a rigorously determined baseline.

This study is limited by a lack of hospitals from small towns and rural areas and it is thought that these settings have an even higher incidence of ADEs. Finally, our study findings are not generalisable to Saudi Arabia overall because the study was conducted in Riyadh only.

In conclusion, ADEs are common in Saudi hospitals, especially in the ICUs, causing significant morbidity and mortality. While there are variations in the incidence of ADEs among countries, there are prospects for preventing them. Interventions that are effective in other countries should be tested in Saudi Arabia. Such interventions may include, but are not limited to, implementation of computerised physician entry with a clinical decision support system,16 involvement of clinical pharmacists as part of the medical team during physicians’ rounds,25–27 medication reconciliation to obtain accurate medication histories at hospital admission, unit transfers during hospitalisation and discharge from hospital,28 and changing the currently available paper-based system to an electronic medical records system.29

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank research assistants, Emad Zalloum, Trig Allam, Maram Abuzaid, Umm Hani Sayeda, Shamailah Osmani, Aishah Nor, Nesreen al-shabr, Sultan Al-Harbi, for their help during the data collection process.

Footnotes

Contributors: HA, DB and MDM designed the study. HA and MAM wrote the manuscript. MAM and YA contributed to the data analysis and management. All authors contributed to the data collection process, the study idea and design, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Plan for Science and Technology (09-BIO708-02).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the institutional review boards of all four hospitals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Bates DW, Spell N, Cullen DJ et al. The costs of adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. Adverse Drug Events Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1997;277:307–11. 10.1001/jama.1997.03540280045032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA 1995;274:29–34. 10.1001/jama.1995.03530010043033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al Hamid A, Ghaleb M, Aljadhey H et al. A systematic review of hospitalization resulting from medicine-related problems in adult patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:202–17. 10.1111/bcp.12293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morimoto T, Sakuma M, Matsui K et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and medication errors in Japan: the JADE study. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:148–53. 10.1007/s11606-010-1518-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aljadhey H, Mahmoud MA, Mayet A et al. Incidence of adverse drug events in an academic hospital: a prospective cohort study. Int J Qual Health C 2013;25:648–55. 10.1093/intqhc/mzt075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benkirane R, Pariente A, Achour S et al. Prevalence and preventability of adverse drug events in a teaching hospital: a cross-sectional study. East Mediterr Health J 2009;15:1145–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stausberg J. International prevalence of adverse drug events in hospitals: an analysis of routine data from England, Germany, and the USA. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:125 10.1186/1472-6963-14-125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gurwitz JH, Field TS, Harrold LR et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA 2003;289:1107–16. 10.1001/jama.289.9.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Seger AC et al. Adverse drug events and medication errors: detection and classification methods. BMJ Qual Saf 2004;13:306–14. 10.1136/qshc.2004.010611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bates DW, Boyle DL, Vander Vliet MB et al. Relationship between medication errors and adverse drug events. J Gen Intern Med 1995;10:199–205. 10.1007/BF02600255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. WHO Definitions (cited 2014). http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/quality_safety/safety_efficacy/trainingcourses/definitions.pdf

- 12.Abdullah DC, Ibrahim NS, Ibrahim MI. Medication errors among geriatrics at the outpatient pharmacy in a teaching hospital in Kelantan. Malays J Med Sci 2004;11:52–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ernawati DK, Lee YP, Hughes JD. Nature and frequency of medication errors in a geriatric ward: an Indonesian experience. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2014;10:413–21. 10.2147/TCRM.S61687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sangtawesin V, Kanjanapattanakul W, Srisan P et al. Medication errors at Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health. J Med Assoc Thai 2003;3:S570–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hug BL, Witkowski DJ, Sox CM et al. Adverse drug event rates in six community hospitals and the potential impact of computerized physician order entry for prevention. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:31–8. 10.1007/s11606-009-1141-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benkirane RR, Abouqal R, Haimeur CC et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and medication errors in intensive care units: a prospective multicenter study. J Patient Saf 2009;5:16–22. 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3181990d51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aljadhey H, Alhossan A, Alburikan K et al. Medication safety practices in hospitals: a national survey in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J 2013;21:159–64. 10.1016/j.jsps.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alkhani S, Ahmed Y, Bin-Sabbar N et al. Current practices for labeling medications in hospitals in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J 2013;21:345–9. 10.1016/j.jsps.2012.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abuyassin BH, Aljadhey H, Al-Sultan M et al. Accuracy of the medication history at admission to hospital in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J 2011;19:263–7. 10.1016/j.jsps.2011.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Al-Ghamdi SA, Mahmoud MA, Alammari MA et al. The outcome of pharmacist counseling at the time of hospital discharge: an observational nonrandomized study. Ann Saudi Med 2012;32: 492–7. 10.5144/0256-4947.2012.492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alshaikh M, Mayet A, Aljadhey H. Medication error reporting in a university teaching hospital in Saudi Arabia. J Patient Saf 2013;9:145–9. 10.1097/PTS.0b013e3182845044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salmasi S, Khan TM, Hong YH et al. Medication errors in the Southeast Asian countries: a systematic review. PLoS ONE 2015;10:e0136545 10.1371/journal.pone.0136545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alsulami Z, Conroy S, Choonara I. Medication errors in the Middle East countries: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2013;69:995–1008. 10.1007/s00228-012-1435-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kucukarslan SN, Peters M, Mlynarek M et al. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2014–18. 10.1001/archinte.163.17.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnipper JL, Kirwin JL, Cotugno MC et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:565–71. 10.1001/archinte.166.5.565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leape LL, Cullen DJ, Clapp MD et al. Pharmacist participation on physician rounds and adverse drug events in the intensive care unit. JAMA 1999;282:267–70. 10.1001/jama.282.3.267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tam VC, Knowles SR, Cornish PL et al. Frequency, type and clinical importance of medication history errors at admission to hospital: a systematic review. CMAJ 2005;173:510515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu M, McPeek Hinz ER, Matheny ME et al. Comparative analysis of pharmacovigilance methods in the detection of adverse drug reactions using electronic medical records. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2013;20:420–6. 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010831supp_appendix.pdf (138.7KB, pdf)