Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to compare the catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) prevalence and its determinants between empty-nest and non-empty-nest elderly households.

Setting

Shandong province of China.

Participants

A total of 2761 elderly households are included in the analysis.

Results

CHE incidence among elderly households was 44.9%. The CHE incidence of empty-nest singles (59.3%, p=0.000, OR=3.19) and empty-nest couples (52.9%, p=0.000, OR=2.45) are both statistically higher than that of non-empty-nest elderly households (31.4%). An inverse association was observed between CHE incidence and income level in all elderly household types. Factors including 1 or more household elderly members with non-communicable chronic diseases in the past 6 months, 1 or more elderly household members being hospitalised in the past year and lower household income, are significant risk factors for CHE in all 3 household types (p<0.05). Health insurance status was found to be a significant determinant of CHE among empty-nest singles and non-empty-nest households (p<0.05).

Conclusions

CHE incidence among elderly households is high in China. Empty-nest households are at higher risk for CHE than non-empty-nest households. Based on these findings, we suggest that special insurance be developed to broaden the coverage of health services and heighten the reimbursement rate for empty-nest elderly in the existing health insurance schemes. Financial and social protection interventions are also essential for identified at-risk subgroups among different types of elderly households.

Keywords: catastrophic health expenditure, elderly, empty-nest, determinants, China

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study attempts to compare the catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) prevalence between empty-nest and non-empty-nest elderly households, a subject that has not previously been studied in the older population in China.

There might be a possible recall bias for most questionnaire data, especially for the self-reported information about out-of-pocket, annual household expenditure and food expenditures, which is a limitation of this study.

The cross-sectional study design precludes any causal interpretation.

Introduction

With a significant increase in average life expectancy and a sharp decline in fertility under the one-child policy in the past three decades, China experienced a considerable increase in absolute and relative numbers of elderly, and joined the ranks of many other ‘ageing societies’ late in the 20th century.1–4 A report released in January 2014 by National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China estimated that there were 202.4 million people aged 60 years and above at the end of 2013 in China, accounting for 14.9% of the total population,5 and representing an increase of 1.6% compared with 2010.6 In recent years, following this trend, a new subpopulation of ‘empty-nest elderly’ has emerged in China.1

Empty-nest elderly refers to those elderly with no children or whose children have already left home. These older people either live alone (empty-nest singles) or with a spouse (empty-nest couples).7 A China Research Center on Aging (CRCA) report shows that the number of empty-nest elderly reached 100 million in 2013, accounting for about 50% of the total elderly population.8 It is estimated that the proportion of empty-nest elderly households will reach 90% by 2030.9 This phenomenon has become an important social problem that cannot be ignored. The subject of healthcare problems facing this population is a critical issue that will have to be addressed in the near future.1–2 10

According to CRCA data, of the 202.4 million elderly in 2013, more than 100 million have non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and more than 37 million have disabilities.8 This will result in an increase in health service needs, healthcare usage and health expenditure among the elderly.11–14 Some researchers have demonstrated that the increase in the proportion of older people in a country is an important driver of national health expenditure.12 15 16 As in many other countries, out-of-pocket (OOP) payments are a primary source of health financing in China, accounting for nearly 34.0% of the total health expenditure.17–19 Coupled with a population with high health needs and poor financial resources, OOP payments are likely to push the elderly into financial catastrophe. Previous studies in China have indicated that households with elderly family members were at high risk of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE).20 21

Some studies have shown that empty-nesters have even poorer physical health status, higher prevalence for chronic diseases and lower income than non-empty-nesters. Empty-nest households may face a greater risk of experiencing CHE than non-empty-nest households.22–25 Protecting people, especially vulnerable people (eg, older people), from CHE is a desirable objective of health policy worldwide.26–29 Health insurance has been seen as an effective way to protect households from CHE. In China, coverage by the health insurance system (including the Urban Employee Basic Medical Insurance, the Urban Resident Basic Medical Insurance and the New Cooperative Medical Scheme (NCMS)) had increased to 95% by the end of 2014. Under a nearly universal coverage of health insurance system, to identify the prevalence and intensity of CHE for empty-nest elderly, and to compare the differences in CHE and its determinants, between empty-nest and non-empty-nest households, can be helpful for the development of policies to protect such populations from financial risk because of ill health. Hence, a detailed study of health expenditure for empty-nest households is of high priority.

Our overall goal was to compare CHE between empty-nest and non-empty-nest households, and our specific objectives were to compare the incidence and intensity of CHE between empty-nest and non-empty-nest households with seniors, and to examine predictors for CHE in the surveyed households.

Methods

Definitions

In this study, we defined ‘elderly’ to include all individuals aged 60 years and above, which is a universally accepted standard in China and also some other countries in Asia-Pacific region. We used the term ‘empty-nest elderly’ (or ‘empty-nesters’) to refer to those elderly with no children or whose children have already left home. These older people either lived alone (empty-nest singles) or with a spouse (empty-nest couples).7

Household capacity to pay was defined as total household expenditure net of food expenditure.30 31 We followed the widely accepted WHO definition for CHE: total household OOP payments equalling or exceeding 40% of the household capacity to pay was considered catastrophic. CHE was usually assessed by incidence and intensity indicators. Mean gap (MG) and mean positive gap (MPG) were used to reflect intensity. The incidence of CHE was defined as OOP payments that equalled or exceeded a threshold share of the household's capacity to pay. In this study, we used 40% as the threshold. MG was the average amount by which OOP payments as a proportion of capacity to pay equalled or exceeded the threshold. MPG was defined as the excess expenditure per household experiencing CHE, equalled to MG/CHE. The specific calculations of CHE incidence and intensity have been described in detail elsewhere.32 33

Study sites and participants

The study was conducted in Shandong province, one of the largest provinces in China. Shandong contains 17 municipalities and 140 counties (districts) with a total population of nearly 97 million in 2012. The number of older people aged 60 years and above was about 15 million, accounting for about 15% of the total population. Of these, nearly 50% were empty-nesters.

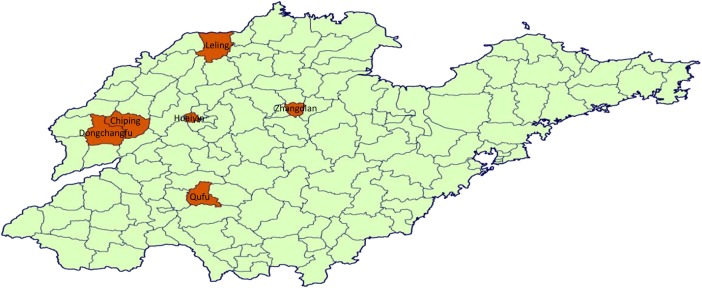

A multistage stratified random cluster sampling method was used. First, the urban districts and rural counties in Shandong province were stratified as three groups according to per capita gross domestic product (GDP). From each group, one district and one county were randomly selected. In total, three districts (Huaiyin, Dongchangfu, Zhangdian) and three counties (Qufu, Chiping, Leling) were selected as study sites (figure 1). Next, the subdistricts and townships in every selected district or county were stratified into three levels according to their per capita GDP, and one subdistrict and one township were randomly selected from each level. Finally, we randomly selected three communities or three villages from each selected subdistrict and township. In all, 27 urban communities and 27 rural villages were selected. All of the elderly households in each sample community/village were recruited for participation in our study. A total of 2950 households were recruited, of which 2761 households with complete data were included in the analysis. Among those we included, 1614 households were empty-nest elderly households. Of the empty-nest households, 51 (3.2%) were those without children, and the rest were those caused by the departure of the children. There were no statistical differences in main health outcomes (NCDs, hospitalisation, see online supplementary table S1) between the empty-nest households from no children and those from departed children. Therefore, we combined the two groups into one defined as empty-nest households when we analysed the data. Of the 189 excluded elderly households, those defined as empty-nest accounted for 48.1%. Around 66.1% of the excluded households had one or more members with NCDs, and 12.2% had one or more elderly members admitted to hospitals.

Figure 1.

Location of the study sites in Shandong province, China.

bmjopen-2015-010992supp_tables.pdf (145.1KB, pdf)

Data collection

A cross-sectional study was conducted by our research team, from November 2011 to January 2012. All the older people were interviewed face-to-face using a questionnaire that included family composition, demographic characteristics, household income, household total expenditure, food expenditure, household OOP payments for health, including direct health expenditures (diagnosis and treatment) and associated non-medical expenses (transport and accommodation costs for patients and companions), health insurance status, and health service needs and usage. Data were collected by trained Masters students from the Shandong University School of Public Health.

Data analysis

In order to ensure quality, the data were double entered and checked using EPI Data V.6.04. The statistical package SPSS V.13.0 was used to analyse the data. Household total expenditure, food expenditure, capacity to pay and OOP payment were presented as means and medians. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to compare the CHE incidence across different types of households. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to assess the explanatory variables for CHE in each type of elderly household. Statistical significance was set at the 5% level.

Ethical consideration

All participants gave their informed written consent for participation prior to the start of study activities.

Results

Complete data were collected from 2761 elderly households. Of these, empty-nest singles accounted for 14.4%, empty-nest couples accounted for 44.0% and non-empty-nest elderly households accounted for 41.5%. Around 51.9% of households were urban and 48.1% were rural. Only 5.5% of households had no health insurance, 23.7% were covered by the Medical Insurance for Urban Employees scheme (MIUE), 13.5% were covered by the Medical Insurance for Urban Residents scheme (MIUR) and 57.2% were covered by the NCMS. Around 67.3% of households had one or more elderly members with NCD, while 16.1% of households had one or more elderly members admitted to hospitals in the 12 months prior to survey administration (table 1). Some variables across different districts or counties were also presented in online supplementary table S2, and interested readers are encouraged to refer to the table for more details.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of sample households in Shandong, China

| Characteristic | Number (households) | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| Observations | 2761 | 100.0 |

| Household composition | ||

| Empty-nest single | 398 | 14.4 |

| Empty-nest couple | 1216 | 44.0 |

| Non-empty-nest elderly | 1147 | 41.5 |

| Residence | ||

| Urban | 1432 | 51.9 |

| Rural | 1329 | 48.1 |

| Household income* | ||

| Q1† | 647 | 23.4 |

| Q2 | 703 | 25.5 |

| Q3 | 698 | 25.3 |

| Q4 | 692 | 25.1 |

| Health insurance‡ | ||

| None | 153 | 5.5 |

| MIUE | 655 | 23.7 |

| MIUR | 374 | 13.5 |

| NCMS | 1579 | 57.2 |

| One or more elderly members with NCD§ | ||

| Yes | 1859 | 67.3 |

| No | 902 | 32.7 |

| One or more elderly members admitted to hospital | ||

| Yes | 445 | 16.1 |

| No | 2316 | 83.9 |

*Twenty households missing household income.

†Quartile 1 (Q1) is the poorest and quartile 4 (Q4) is the richest.

‡MIUE, Medical Insurance for Urban Employees scheme; MIUR, Medical Insurance for Urban Residents scheme; NCMS, New Cooperative Medical Scheme.

§NCD, non-communicable chronic disease.

Mean annual household expenditure was US$2405,i with the highest mean expenditure among non-empty-nest households (US$2905), and the lowest mean expenditure among empty-nest singles (US$1152; table 2). Mean household food expenditure was US$1108 (with a median of US$794) and capacity to pay was US$1294 (with a median of US$873). Mean annual household OOP payment was US$559 (median of US$317), accounting for 43.2% of the mean household capacity to pay. At 53.2%, empty-nest singles had the highest share of OOP payments compared with household capacity to pay, while non-empty-nest households had the lowest share, at 34.9%.

Table 2.

Distribution of capacity to pay and OOP costs for healthcare across elderly households in Shandong, China

| Indicators | Empty-nest single | Empty-nest couple | Non-empty-nest elderly | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | 398 | 1216 | 1147 | 2761 |

| Average OOP* cost of healthcare (US$)† | ||||

| Mean‡ | 343 | 665 | 526 | 559 |

| Median | 160 | 304 | 317 | 317 |

| Average annual household expenditure (US$) | ||||

| Mean | 1152 | 2362 | 2905 | 2405 |

| Median | 815 | 1677 | 2413 | 1905 |

| Average annual household food expenditure (US$) | ||||

| Mean | 506 | 1046 | 1390 | 1108 |

| Median | 383 | 799 | 1270 | 794 |

| Average capacity to pay (US$)§ | ||||

| Mean | 645 | 1315 | 1508 | 1294 |

| Median | 415 | 831 | 1111 | 873 |

| OOP cost as share of capacity to pay (%) | 53.2 | 50.6 | 34.9 | 43.2 |

*OOP, out-of-pocket.

†Currency exchange rate of Chinese ¥RMB630 to US$100 (at the end of 2011).

‡There is a statistically significant difference for the mean OOP cost of health across different types of elderly households (F=12.60, p=0.000).

§Capacity to pay is calculated as household expenditure minus food expenditure.

We found that CHE incidence, on average, was 44.9% among the elderly households. To understand the correlation between household type and CHE, we compared the CHE incidence across different household types using a univariate logistic regression model. The model showed that CHE incidence was highest among the empty-nest singles (59.3%), and was lowest among the non-empty-nest elderly households (31.4%). This difference was statistically significant (table 3). An inverse association was observed between CHE incidence and household income levels (table 4). Nearly 60% of households in the poorest quintile (Q1) experienced CHE compared with around 33% of those in the richest quintile (Q4). Similar trends were observed across all of the three types of elderly households. In nearly every income level, CHE incidence was highest among empty-nest singles and lowest in non-empty-nest households.

Table 3.

Incidence of catastrophic expenditure for healthcare across different household living arrangements in Shandong, China

| Household composition | Households | CHE* | Per cent | OR | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-empty-nest elderly | 1147 | 360 | 31.4 | 1.0 | ||

| Empty-nest single | 398 | 236 | 59.3 | 3.19 | 2.52 to 4.03 | <0.001 |

| Empty-nest couple | 1216 | 643 | 52.9 | 2.45 | 2.07 to 2.90 | <0.001 |

| Total | 2761 | 1239 | 44.9 |

*CHE, catastrophic health expenditure.

Table 4.

Incidence and intensity of CHE by economic status and household composition in Shandong, China

| CHE* | Empty-nest single | Empty-nest couple | Non-empty-nest elderly | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC (%) | ||||

| Q1† | 61.6 | 62.5 | 47.7 | 58.7 |

| Q2 | 60.0 | 53.7 | 39.8 | 49.1 |

| Q3 | 53.0 | 49.5 | 27.9 | 39.0 |

| Q4 | 47.1 | 46.6 | 20.3 | 33.1 |

| Total | 59.3 | 52.9 | 31.4 | 44.9 |

| Mean catastrophic payment gap (%) | ||||

| Q1 | 19.4 | 21.3 | 12.8 | 18.7 |

| Q2 | 17.5 | 16.0 | 10.6 | 14.1 |

| Q3 | 12.2 | 12.6 | 6.9 | 9.7 |

| Q4 | 9.6 | 10.7 | 4.9 | 7.5 |

| Total | 17.3 | 15.1 | 7.8 | 12.4 |

| Mean positive gap (%) | ||||

| Q1 | 31.5 | 34.0 | 26.9 | 31.8 |

| Q2 | 29.1 | 29.8 | 26.7 | 28.7 |

| Q3 | 23.0 | 25.6 | 24.6 | 24.9 |

| Q4 | 20.4 | 22.9 | 22.0 | 22.6 |

| Total | 29.2 | 28.5 | 25.2 | 27.7 |

*CHE, catastrophic health expenditure.

†Quartile 1 (Q1) is the poorest and quartile 4 (Q4) is the richest.

HC, head count.

On average, CHEs were 12.4 percentage points higher than 40%, with the highest MG (17.3 percentage points) appearing among empty-nest singles and the lowest MG (7.8 percentage points) appearing among non-empty-nest households. The MPG measure indicated that elderly households experiencing CHE spent an average of 67.7% of their capacity to pay on healthcare (27.7 percentage points over 40%).

A series of logistic regression models was conducted to examine the risk factors of CHE for each of the three subgroups separately. This allowed for a more complete understanding of the unique determinants of CHE for each subgroup (table 5). Three factors were found to be statistically significant (p<0.05) risk factors in all three types of households: the presence of one or more household elderly with NCDs in the past 6 months, the hospitalisation of one or more elderly household members in the past year and a lower household income. Among empty-nest singles, those who were uninsured were more likely to experience CHE than those covered by NCMS (OR=0.28, p=0.044) or MIUR (OR=0.27, p=0.034). Among non-empty-nest households, those elderly who were uninsured were more likely to have CHE than those covered by NCMS (OR=0.48, p=0.044), and rural households were more likely to have CHE than their urban counterparts (OR=1.60, p=0.035).

Table 5.

Logistic regression model of determinants of CHE* for healthcare of different kinds of elderly households in Shandong, China

| Variables | Empty-nest single (model 1) |

Empty-nest couple (model 2) |

Non-empty-nest elderly (model 3) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ORadj | 95% CI | p Value | ORadj | 95% CI | p Value | ORadj | 95% CI | p Value | |

| Residence | |||||||||

| Urban | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Rural | 1.11 | 0.48 to 2.57 | 0.809 | 0.84 | 0.56 to 1.25 | 0.380 | 1.60 | 1.03 to 2.49 | 0.035 |

| Household income† | |||||||||

| Q4 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Q1 | 7.40 | 2.17 to 25.29 | 0.001 | 2.18 | 1.36 to 3.45 | 0.001 | 5.78 | 3.52 to 9.50 | <0.001 |

| Q2 | 5.53 | 1.66 to 18.36 | 0.005 | 1.40 | 0.92 to 2.15 | 0.121 | 3.49 | 2.30 to 5.30 | <0.001 |

| Q3 | 1.67 | 0.52 to 5.36 | 0.391 | 1.11 | 0.78 to 1.58 | 0.550 | 1.59 | 1.07 to 2.35 | 0.020 |

| One or more elderly members with NCD‡ | |||||||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Yes | 6.28 | 3.61 to 10.93 | <0.001 | 2.56 | 1.96 to 3.35 | <0.001 | 8.44 | 5.61 to 12.72 | <0.001 |

| One or more elderly members admitted to hospital | |||||||||

| No | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| Yes | 4.35 | 2.05 to 9.22 | <0.001 | 2.48 | 1.75 to 3.51 | <0.001 | 4.79 | 3.20 to 7.17 | <0.001 |

| Health insurance§ | |||||||||

| None | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ||||||

| MIUE | 0.89 | 0.26 to 3.08 | 0.849 | 0.69 | 0.40 to 1.19 | 0.181 | 0.94 | 0.46 to 1.94 | 0.874 |

| MIUR | 0.27 | 0.08 to 0.93 | 0.038 | 1.02 | 0.56 to 1.86 | 0.942 | 0.70 | 0.33 to 1.50 | 0.358 |

| NCMS | 0.28 | 0.08 to 0.97 | 0.044 | 1.12 | 0.62 to 2.04 | 0.708 | 0.48 | 0.24 to 0.98 | 0.044 |

| Observations | 394 | 1210 | 1136 | ||||||

| R2 | 0.277 | 0.132 | 0.342 | ||||||

*CHE, catastrophic health expenditure.

†Quartile 1 (Q1) is the poorest and quartile 4 (Q4) is the richest.

‡NCD, non-communicable chronic disease.

§MIUE, Medical Insurance for Urban Employees scheme; MIUR, Medical Insurance for Urban Residents scheme; NCMS, New Cooperative Medical Scheme.

Discussion

We find that the incidence of CHE among elderly households is 44.9%. This is significantly higher than the incidence of CHE identified by other scholars researching this topic in China (and who used an identical definition and calculation for CHE). For example, one 2009 study in Urban Mei County of Shaanxi province found that the CHE incidence was 7.7% among the general population.34 Another study using data from the China Fourth National Health Service Survey (2008) found that the CHE incidence was 13.0%.20 A 2009 study of rural households in Anhui province also found a CHE incidence of around 13.85%.35 Another study, in 2011, conducted in the same province as our study, showed that the CHE incidence was 26.5% among the entire population36—a full 18.4 percentage points below our observed incidence among the elderly. The highest incidence of CHE that we could find in the literature came from a 2006 study by Xining and Yinchuan; however, at 39.4%, this rate was still over 5 percentage points below our observed rate among the elderly in Shandong province.37 Previous studies identified the CHE incidence among the general population. We focused only on the elderly households—a population with higher health needs and lower income than the general population—among which empty-nest households had even higher healthcare needs and worse economic conditions (see online supplementary table S3). The high CHE incidence in our study could be explained mainly by the differences in age and family structure of the participants.

Our results further show that empty-nest households are at higher risk of experiencing CHE than are non-empty-nest households. This is not surprising, since previous studies have already shown that the empty-nest elderly have poorer physical health status (eg, higher rates of chronic diseases) compared with non-empty-nest elderly.22–24 As a subgroup with poorer health conditions and lower incomes, the empty-nest elderly, especially empty-nest singles, might be expected to experience higher CHE than non-empty-nest elderly. That our work confirms this hypothesis underlines the need for policymakers to develop special insurance supplements within existing health insurance schemes (NCMS, MIUE, MIUR) to broaden the coverage of health services and also heighten the reimbursement rate for empty-nest elderly.

Consistent with other studies, our results also show that economic status is a key risk factor for CHE in all three types of elderly households.20 30 Across all household types, elderly in lower income quintiles are at higher risk of suffering CHE. Within the same quintile, CHE incidence among empty-nest households is higher than that among non-empty-nest households. Likewise, households in lower income quintiles have higher MG and MPG than those in richer quintiles, and this holds true across all three household types. Empty-nest households also have higher MG and MPG than do non-empty-nest households. These findings indicate the importance—especially for low-income empty-nest households, known as ‘Dibaohu’ in China—of living and medical aids from municipal governments and other welfare programmes. Such programmes have the potential to reduce the risk of CHE for the most vulnerable households.

The primary policy aim of health insurance is to protect households from catastrophe or impoverishment.38 Our findings show that, while existing health insurance schemes provide some financial protection for empty-nest singles and non-empty-nest households, this protection is insufficient. Nearly 95% of sampled households were covered by some type of health insurance scheme, but 59.3% of empty-nest singles and 31.4% of non-empty-nest households still face CHEs even after reimbursement. This contradiction indicates a need for government to pay more attention to increasing health insurance coverage amounts, now that population coverage is reasonably high.

We were somewhat surprised to observe that the differences between empty-nest couples with and without health insurance are not as significant as expected. One possible explanation for this finding is that uninsured households may refuse or fail to seek treatment when faced with serious illness, thereby reducing financial risk. Another possible explanation might stem from the adverse selection inherent in voluntary insurance schemes such as NCMS.39 Third, China has nearly reached universal coverage by its health insurance system, and only a rather low proportion of households have no health insurance schemes at all. In this study, only 153 (5.5%) elderly households had no insurance. The result might be affected, to some extent, by the representativeness of these households when we used such a small sample for comparisons.

Similar with previous studies,20 36 our results also show that households facing illness (defined as having one or more elderly family members with NCDs in the past 6 months, or having one or more elderly family members admitted to the hospital in the past year) are more likely to suffer CHE, regardless of household type. This finding has important implications for policymakers who aim to develop financial and social protection interventions to better protect at-risk groups. For example, adding insurance coverage for NCD outpatient care or higher reimbursement levels for NCD inpatient services might help to shield patients with NCD from high OOP expenditures.

There are some limitations in this study. First, the fact that some patients who ought to but choose not to seek health services due to perceived financial barriers likely means that the CHE incidence and intensity figures we report here are slightly underestimated. Second, since we collected self-reported information about OOP, annual household expenditure and food expenditures, we cannot exclude the possibility that recall bias is an issue. Third, only 153 (5.5%) elderly households in this study had no insurance. The representativeness of these households may affect the result as we used a small sample for comparisons.

Conclusion

This study shows that CHE incidence is high among elderly households in China. Empty-nesters, including empty-nest singles and empty-nest couples, are at higher risk of CHE than non-empty-nest households. These results imply a need for a special insurance to broaden the coverage of health services and heighten the reimbursement rate in existing health insurance schemes so as to reduce the financial burden on empty-nest households. The elderly households with one or more NCD members were found to have higher risk of CHE, which for decision-makers implies developing an extra benefit package for chronic seniors. We further find that CHE incidence and intensity are both inversely associated with household income across all household types, suggesting a need for modification of existing health insurance and medical aid schemes to make them more pro-poor. Furthermore, this study also identifies a number of risk factors for CHE among different kinds of elderly households, which are useful to design targeted policies that can reduce the risk of CHE among at-risk subgroups.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the officials of the local health agencies and all participants and staff at the study sites, for their cooperation.

Contributors: TY, CZ and AM conceived the idea. CZ, JC and WZ implemented the field study. TY, CZ, JC, AM, LS and JL participated in the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results. TY and CZ drafted the manuscript. JC and AM gave many valuable comments on the draft and also polished it. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors are grateful for funding support from the National Science Foundation of China (71003067), and the Innovation Foundation of Shandong University (2012DX006, 2009TS012).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Ethical Committee of Shandong University School of Public Health approved the study protocol.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Currency exchange rate end 2011: ¥RMB630 to US$100.

References

- 1.Zhou C, Chu J, Xu L. Considering anew on health problems in Chinese urban areas at the initial stages of 21st century. J Med Philos 2006;27:19–21. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lv XL, Jiang YH, Sun YH et al. Short form 36-item Health Survey test result on the empty nest elderly in China: a meta-analysis. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 2013;56:291–7. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.10.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qi L. Analysis on “empty-nesters”—a worthy social issue of social concern. S China Popul 1999;14:18–20. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.China National Committee on Aging. China stepped into aging society in 1999, and the number of the elderly ranks in the first in the world. Xi'an Evening News, 2006. http://www.xiancn.com/gb/news/2006-02/24/content_799130.htm (accessed 4 Sep 2014) [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China. China national economic development undermines stable increase in 2013. China government website, 2014. http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2014-01/20/content_2570763.htm (accessed 4 Sep 2014 [in Chinese]). [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Bureau of Statistics of People's Republic of China. The Sixth China National Census data in 2010 (No. 1). China statistical government website, 2011. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/rkpcgb/qgrkpcgb/201104/t20110428_30327.html (accessed 4 Sep 2014) [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu ZQ, Sun L, Sun YH et al. Correlation between loneliness and social relationship among empty nest elderly in Anhui rural area, China. Aging Ment Health 2010;14:108–12. 10.1080/13607860903228796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu YS, Dang JW. China report of the development on aging cause Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2013. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li DM, Chen TY, Li GY. The problem of mental health in the elderly in empty-nest family. Chin J Gerontol 2003;23:405–7. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang Y, Wu W. Exploratory analysis of health-related quality of life among the empty-nest elderly in rural China: an empirical study in three economically developed cities in eastern China. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2014;12:59 10.1186/1477-7525-12-59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Somkotra T, Lagrada LP. Which households are at risk of catastrophic health spending: experience in Thailand after universal coverage. Health Aff 2009;28:w467–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brinda EM, Rajkumar AP, Enemark U et al. Nature and determinants of out-of-pocket health expenditure among older people in a rural Indian community. Int Psychogeriatr 2012;24:1664–73. 10.1017/S104161021200083X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albanese E, Liu Z, Acosta D et al. Equity in the delivery of community healthcare to older people: findings from 10/66 Dementia Research Group cross-sectional surveys in Latin America, China, India and Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:153 10.1186/1472-6963-11-153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XQ, Chen PJ. Population ageing challenges health care in China. Lancet 2014;383:870 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60443-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006;3:e442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brinda EM, Andrés RA, Enemark U. Correlates of out-of-pocket and catastrophic health expenditures in Tanzania: results from a national household survey. BMC Int Health Hum Rights 2014;14:5 10.1186/1472-698X-14-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.China National Health Development Research Centre. China health account report 2013 Beijing: China Statistical Yearbook Press, 2014. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tambor M, Pavlova M, Woch P et al. Diversity and dynamics of patient cost-sharing for physicians’ and social services in the 27 European Union countries. Eur J Public Health 2011;21:585–90. 10.1093/eurpub/ckq139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bock JO, Matschinger H, Brenner H et al. Inequalities in out-of-pocket payments for health care services among elderly Germans–results of a population-based cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:3 10.1186/1475-9276-13-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Wu Q, Xu L et al. Factors affecting catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment from medical expenses in China: policy implications of universal health insurance. Bull World Health Organ 2012;90:664–71. 10.2471/BLT.12.102178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yan J, Hao N, Liao S et al. The changes and influencing factors on catastrophic health expenditures before and after new health care reform: based on the sample survey in Mei County ‘Shanxi Province. Chin J Health Policy 2013;6:30–3. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou C, Chu J, Liu D et al. Comparison of health need and utilization between empty-nest and non-empty-nest aging population in urban communities: a sample survey based on Jinan City. Chin J Health Policy 2012;5:24–9. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu X, Zhu X, Jiang W et al. Analysis on physical health status among 585 empty-nest older people in Wenzhou City. Chin J Gerontology 2006;26:751–3. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu LJ, Sun X, Zhang CL et al. Health-care utilization among empty-nesters in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Public Health Rep 2007;122:407–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu LJ, Guo Q. Life satisfaction in a sample of empty-nest elderly: a survey in the rural area of a mountainous county in China. Qual Life Res 2008;17:823–30. 10.1007/s11136-008-9370-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.WHO. The world health report 2000: health systems: improving performance Geneva: World Health Organization, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 27.WHO. The world health report 2002 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K et al. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet 2003;362:111–17. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kawabata K, Xu K, Carrin G. Preventing impoverishment through protection against catastrophic health expenditure. Bull World Health Organ 2002;80:612. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su TT, Kouyaté B, Flessa S. Catastrophic household expenditure for health care in a low-income society: a study from Nouna District, Burkina Faso. Bull World Health Organ 2006;84: 21–7. doi:/S0042-96862006000100010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chuma J, Maina T. Catastrophic health care spending and impoverishment in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:413 10.1186/1472-6963-12-413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.O'Donnell O, van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A et al. Analyzing health equity using household survey data: a guide to techniques and their implementation. Washington DC: The World Bank, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E. Catastrophe and impoverishment in paying for health care: with applications toVietnam 1993–1998. Health Econ 2003;12:921–34. 10.1002/hec.776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yan J, Yan Y, Gao J et al. Research of the impact of out-of-pocket payments on catastrophe and impoverishment of urban residents in Shaanxi province. Chin Health Econ 2012;31:25–8. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang L, Jiang Q, Wang A et al. Analysis on catastrophic health spending of rural inhabitant in Anhui province. Chin J Health Policy 2012;5:59–62. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen R, Yin A, Zhao W et al. Catastrophic health expenditure and its determinants among rural residents in Tengzhou City. Chin Health Econ 2012;31:19–21. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun X, Clas R, Meng Q. Analysis on catastrophic health expenditure among urban residents in Xining and Yinchuan City. Chin Health Serv Manag 2008;25:12–15. [in Chinese]. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Cheng X, Tolhurst R et al. How effectively can the New Cooperative Medical Scheme reduce catastrophic health expenditure for the poor and non-poor in rural China? Trop Med Int Health 2010;15:468–75. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02469.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jiang C, Ma J, Zhang X et al. Measuring financial protection for health in families with chronic conditions in Rural China. BMC Public Health 2012;12:988 10.1186/1471-2458-12-988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2015-010992supp_tables.pdf (145.1KB, pdf)