Abstract

Introduction

There is a lack of evidence in the efficacy of the coupled plasma filtration adsorption (CPFA) to reduce the mortality rate in septic shock. To fill this gap, we have designed the ROMPA study (Mortality Reduction in Septic Shock by Plasma Adsorption) to confirm whether treatment with an adequate dose of treated plasma by CPFA could confer a clinical benefit.

Methods and analysis

Our study is a multicentric randomised clinical trial with a 28-day and 90-day follow-up and allocation ratio 1:1. Its aim is to clarify whether the application of high doses of CPFA (treated plasma ≥0.20 L/kg/day) in the first 3 days after randomisation, in addition to the current clinical practice, is able to reduce hospital mortality in patients with septic shock in intensive care units (ICUs) at 28 and 90 days after initiation of the therapy. The study will be performed in 10 ICUs in the Southeast of Spain which follow the same protocol in this disease (based on the Surviving Sepsis Campaign). Our trial is designed to be able to demonstrate an absolute mortality reduction of 20% (α=0.05; 1−β=0.8; n=190(95×2)). The severity of the process, ensuring the recruitment of patients with a high probability of death (50% in the control group), will be achieved through an adequate stratification by using both severity scores and classical definitions of severe sepsis/septic shock and dynamic parameters. Our centres are fully aware of the many pitfalls associated with previous medical device trials. Trying to reduce these problems, we have developed a training programme to improve the CPFA use (especially clotting problems).

Ethics and dissemination

The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committees of all the participant centres. The findings of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, as well as national and international conference presentations.

Trial registration number

NCT02357433; Pre-results.

Keywords: INFECTIOUS DISEASES, STATISTICS & RESEARCH METHODS

Introduction

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome characterised by systemic inflammation due to infection.1 Experimental studies show that infusion of bacterial products leads to rapid systemic release of an array of proinflammatory mediators.2 These mediators are thought to play a role in consequent organ injury or death. Although initially much of the interest in sepsis focused on the proinflammatory response or single inflammatory mediators,3–6 it is now clear that infection often triggers a complex, variable and prolonged host response.7 8 While both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mechanisms can contribute to the resolution of infection and tissue recovery, an inappropriate response consisting of an excess (or deficiency) of mediators, inappropriate timing or location can lead to organ injury and secondary infections.

Sepsis is still a leading cause of mortality in intensive care unit (ICU) patients with a mortality rate of severe sepsis and septic shock ranging from 20% to 50%.9 The Surviving Sepsis Campaign, an international consortium of professional societies involved in critical care, treatment of infectious diseases and emergency medicine, recently issued the third edition of the clinical guidelines for the management of severe sepsis and septic shock.10 However, despite the high prevalence, there is still no consensus on the concise definition and poor evidence for many therapeutic strategies.11–14

One of the great disappointments during the past 30 years has been the failure to apply advances in our understanding of the biological features of sepsis into effective new therapies. Many reasons have been proposed for the numerous failed therapeutic approaches and clinical trials. These include inappropriate targets, targeting specific molecules that are part of redundant pathways, inappropriate timing and incorrect translation of oversimplified animal models to the more complex conditions and timing of human sepsis. In addition, many trials have been strongly criticised for incorrect trial design or execution.13

Theoretically, extracorporeal therapies can be used to remove septic mediators from the bloodstream of critically ill patients.14 15 In practice, however, inflammatory mediators are often poorly removed by conventional diffusion or convection due to the large molecular weight or biophysical size of many cytokines. Even with very high filtration volumes, many cytokines are not able to pass through the pores of commonly used filters.16 Additionally, use of high-permeable membranes or excess filtration can be associated with loss of albumin and other physiological proteins and components. A recent systemic review found that there was no evidence for clinical benefit of high-volume haemofiltration for sepsis.17

Over the past several years, there has been an increased interest in the use of adsorption to aid in the removal of mediators during extracorporeal therapies.14 15 This can be done by adsorption to a membrane during passage of blood through a haemofilter (haemoperfusion), where mediators are adsorbed to the membrane surface; or by adsorption with a cartridge containing resin in either haemoperfusion or plasma perfusion. Although adsorptive techniques have been used for nearly 50 years, there is a relative lack of data regarding clinical efficacy for conditions such as sepsis.

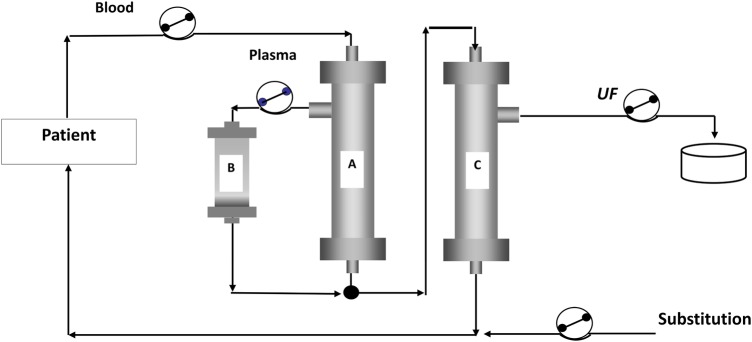

Coupled plasma filtration adsorption (CPFA) has been proposed as one method to non-specifically remove both proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators.18 19 This technique consists of a combination of filters and a resin cartridge to remove a number of different cytokines including tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-6 and IL-10, while simultaneously providing continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT) for renal/fluid support. The entire CPFA process can be divided into four phases: (1) the partial separation of plasma from whole blood by a plasma filter; (2) the removal of sepsis mediators by a cartridge-containing miniature spheres of a synthetic hydrophobic resin; (3) reinfusion of the purified plasma before the haemofilter and finally (4) haemofiltration (figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

AMPLYA system from Bellco Societa unipersonales a r.l. The resin cartridge and plasma filter are in position and ready for use. The copyright holder (Bellco) has approved the usage of this figure.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the CPFA circuit. The extracorporeal circuit consisting of a plasma filter (A), a resin cartridge (B) and a high-flux dialyser (C). Blood pass through a plasma filter, extracted plasma is purified by adsorption on a resin cartridge and the reconstituted blood (●) flows through a high-permeability haemofilter, in which convective exchanges are realised in a postdilution mode (substitution). The copyright holder (Bellco) has approved the usage of this figure. CPFA, coupled plasma filtration adsorption; UF, ultrafiltrate.

CPFA was first used in the late 1990s with subsequent publications of several small observational clinical reports and case studies.20–26 A few years ago, a large randomised multicentre controlled trial was performed by a group of Italian intensive care physicians, GiViTI, but the trial was stopped for futility.27 Factors leading to early stopping were extensively analysed by the investigators and focused primarily on technical problems and the inability to achieve an appropriate dose of treated plasma. Nearly 50% of the patients did not achieve the target goal of 10 hours of treatment/day. In a per protocol analysis, the COMPACT I patients treated with CPFA with a dose of treated plasma superior to 0.20 L/kg/day showed a reduction in the mortality rate compared with control patients or those who received a lesser dose of treated plasma. Although this was an interesting finding, it is necessary to carry out a randomised clinical trial to confirm whether treatment with an adequate dose of treated plasma by CPFA could confer a clinical benefit.

The aim of the ROMPA study (Reduccion de la Mortalidad Mediante Plasma-Adsorción en Shock séptico—Mortality Reduction in Septic Shock by Plasma Adsorption) is to clarify whether the application of high doses of CPFA in addition to the current clinical practice is able to reduce hospital mortality in patients with septic shock in ICUs.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Primary outcome: The main objective is to assess whether the treatment of septic shock associated with standard clinical practice, with the addition of CPFA at high doses (treated plasma volume equal or superior to 0.2 L/kg/day), is able to reduce hospital mortality of patients with septic shock at 28 and 90 days after initiation of therapy.

Secondary outcome: Resolution time of septic shock, expressed in terms of normalisation of plasma lactate, weaning from vasoactive medications and reduction of ICU length of stay (expressed as number of days without septic shock) on the intervention group compared with the control group.

Methods

Setting and participants

The study will be performed in 10 ICUs, in the Southeast of Spain, that follow the same protocol in the treatment of septic shock, based on the recommendations of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign with the participation of the following centres: Vega Baja Hospital of Orihuela, General University Santa Lucía Hospital of Cartagena, University Hospital of San Juan de Alicante, Lluís Alcanyís Hospital of Xàtiva, Marina Baixa Hospital of Villajoyosa, General University Hospital of Alicante, La Plana Hospital of Villarreal, Francesc de Borja Hospital of Gandía, Vinalopó University Hospital of Elche and University Hospital of Torrevieja.

The ROMPA study is a multicentric, randomised, prospective, open clinical trial with a 28-day and 90-day follow-up and allocation ratio 1:1, assessing the mortality reduction by CPFA in patients with septic shock.

Each centre must obtain technical proficiency with the machine and CPFA treatment before they can become ‘activated’ for enrolment by the investigator monitoring team. This was done to avoid similar problems as those reported for COMPACT I, and also because CPFA is not routinely done in Spain and there is a new generation machine now used for CPFA with improved anticoagulation support.

Participants and sample size

Patients aged ≥18 years admitted to the ICU of the participant hospitals with a diagnosis of septic shock can be included in the study. Definition of septic shock is: documented or probable infection with systemic manifestations, accompanied by signs of organ dysfunction or tissue hypoperfusion and with persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation (at least 30 mL/kg of crystalloid), in the absence of other causes of hypotension.

Moreover, the inclusion criteria comprise: (1) identification of the source of infection in the first 12 hours of diagnosis; (2) severity of clinical situation, defined by Acute Physiology and Chronic. Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score, which must be between 20 and 37 points; (3) the time between septic shock diagnosis and randomisation is 12 hours maximum. The choice of timing to start was based on previous experience from the COMPACT study and actual clinical use of routine users (data provided by manufacturer). We think, however, that an early start is better for the patient to avoid further amplification of the inflammatory cascade.

The probability of death in this population in the internal experience of the participating centres is about 50%. We have a higher mortality than what is typically reported in recent literature due to a high percentage of abdominal surgical patients. The observation of a high mortality rate in patients with septic shock from abdominal origin is a classic finding in the scientific papers.28 The European and North American experience of intra-abdominal sepsis is similar, with reported mortality rates for this condition ranging between 30% and 60%. Irrespective of the surgical strategies employed, laparotomy in the critically ill is associated with significant morbidity and mortality, the incidence of which increases with each relaparotomy.29

Finally, we will exclude: (1) patients under the age of 18 years; (2) pregnant patients; (3) patients with pathologies for which expected survival is <90 days (we analyse the mortality at 28 and 90 days. So we thought that it makes sense to exclude patients with comorbidities involving a life expectancy less than that period of time. In any case, this prognosis would not be set by the ICU team but by the respective medical teams treating these pathologies); (4) presence of contraindications (absolute or relative) to extrarenal depuration techniques and (5) lack of informed consent.

We plan to enrol 190 patients with a diagnosis of septic shock in order to demonstrate a reduction in mortality of 20% (similar to that of a subgroup of COMPACT I patients in which the volumes of treated plasma reach a level of at least 0.20 L/kg/day) with an α of 0.05 and a power of the contrast of 80%.30 Our working hypothesis is based on COMPACT I observation in which in an intention-to-treat analysis there was no statistical difference in hospital mortality (47.3%, controls; 45.1%, CPFA; p=0.76), but in a subgroup analysis, patients who could get a dose of treated plasma superior than 0.20 L/ kg/day had a lower mortality compared with controls (OR=0.36, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.99).27 The limit of this per protocol analysis are evident (definition for the per protocol analysis was based on characteristics measured after randomisation, the subgroup allocation may have been influenced by the outcome, etc). In consequence, our objective is to test this hypothesis in a clinical trial with enough power and potency.

Retrospective analysis of the clinical activity of the ICU involved in the previous year allowed us to expect a total admission of 300 cases per year in all participating hospitals. Since only one-third of these patients are likely to meet the inclusion/exclusion requirements, we could complete the clinical trial within 2 years. The recruitment period is preset between March 2015 and March 2017.

Given the characteristics of the study population, with expectations of a long hospital stay (at best) and consequence (comorbidity), which also determine the need for the patients to remain in contact with the hospital system, we do not expect losses to follow-up at 28 and 90 days.

Interventions

The patient is considered registered once the informed consent form has been obtained by the patient or legal representative. The recruitment process ends with the patient randomisation.

Patients will be divided randomly into two arms (control and intervention).

ROMPA has a stratified randomisation based on gender, age (≤65 or >65 years) and Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) III score (<50 or ≥51).

The characteristics of the groups are:

Control group: Treatment following the suggestions provided by the recent surviving sepsis guidelines, as well as standard care guidelines typically followed in Spain. CRRT, continuous veno-venous haemofiltration for both renal (such as acute kidney injury) or non-renal (such as fluid overload) are permitted in both trial arms if these are routinely used. We will not permit the introduction of non-routine extracorporeal or pharmaceutical agents for sepsis during the study to avoid confounding factors.

Intervention group: Same protocol plus high doses of CPFA in the first 3 days after randomisation. Once the patient is placed in the CPFA group, he/she will receive treatment with CPFA immediately. The treatment time will be necessary to achieve the treated plasma dose of 0.2 L/kg/day. Patients will receive a minimum of three sessions and a maximum of five. Regarding the 3-day duration of CPFA, this was also suggested by the manufacturer as the typical shorter usage of CPFA. It is possible for the physician to use CPFA for a longer period if necessary.

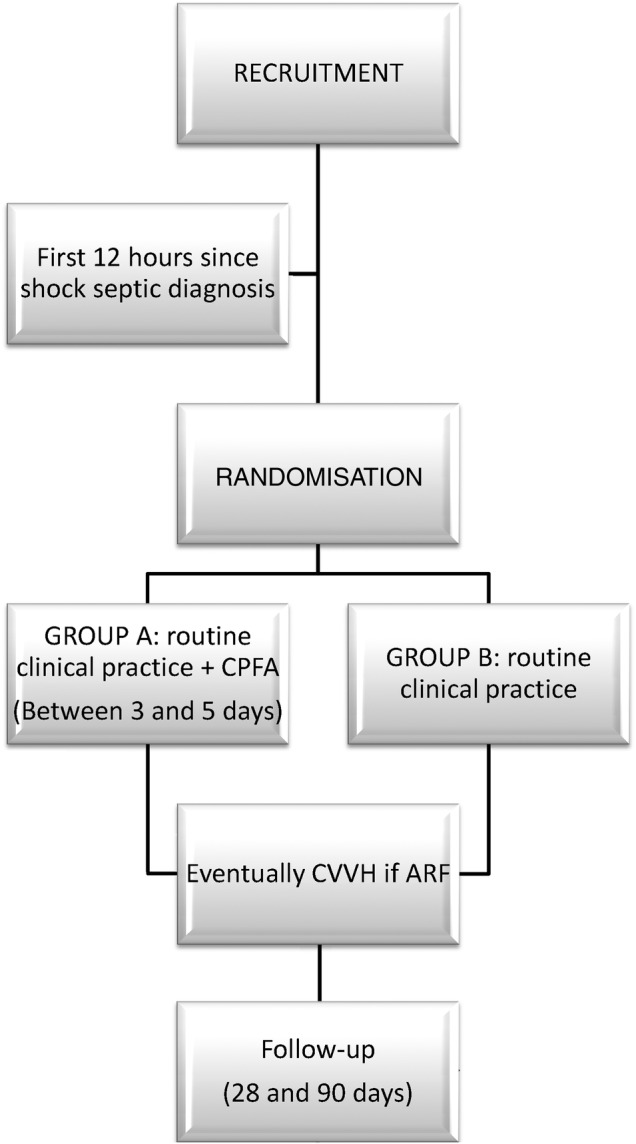

The scheme of the trial is displayed in figure 3.

Figure 3.

Study diagram. This shows the general study design and includes: (1) registration: the patient is considered ‘enrolled’ once informed consent has been obtained. (2) Recruitment phase: must occur within the first 12 hours of septic shock diagnosis. (3) Randomisation: group A (CPFA) or group B (control). (4) Statistical evaluations: at the end of the study and after follow-up. ARF, acute renal failure; CPFA, coupled plasma filtration adsorption; CVVH, continuous veno-venous haemofiltration.

Variables and measurements

The primary outcome is all-cause mortality assessed at 28 and 90 days from the recruitment of the patient. Moreover, at the descriptive level and in order to check the homogeneity of both groups, the following variables will be collected at the time of recruitment: birth year, gender, height, dry weight, body temperature, heart rate, blood pressure, count blood cell, coagulation values (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, international normalised ratio), glucose level, plasma creatinine, bilirubinaemia, plasma C reactive protein, procalcitonin level, blood gas analysis, lactate, urinary output (mL/kg/hours), arterial oxygen tension/fractional inspired oxygen ratio. APACHE II, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) and SAPSIII scores.

Finally, for surviving patients, the following variables will be obtained at a descriptive level: length of stay in ICU (days), normalising times for lactate levels and vasoactive support suspension expressed in hours.

Statistical analysis

The descriptive analysis will be performed using means and SDs for quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for qualitative variables. To verify the homogeneity of both groups, χ2 (Pearson or Fisher) and t-test will be used. To determine the benefit of our intervention, the clinical relevance indicators will be calculated: relative risk, absolute risk reduction, relative risk reduction, number needed to treat.

All analyses will be performed with a significance of 5% and the associated CI of each relevant parameter will be calculated. The statistical software used will be the IBM SPSS Statistics V.22.

The entire analysis will be undertaken with ‘the intention-to-treat’ principle, even though we have foreseen a ‘by protocol’ analysis. Only patients who have received at least the minimum established doses of CPFA treatment in the experimental arm will be evaluated.

The ‘by protocol’ analysis will include the fulfilment of the following requirements: (1) at least three CPFA sessions; (2) total volume of treated plasma >0.2 L/kg day in a minimum of 66% of total sessions; (3) total volume of treated plasma throughout the total number of sessions, once divided by the number of sessions, should result in a mean treated plasma of ≥0.18 L/kg/day.

Discussion

The present study should hopefully confirm the hypothesis showed by ‘per protocol’ analysis of the COMPACT I study and provide answers about the efficacy of early (<12 hours from diagnosis) high-dose CPFA treatment in patients with septic shock.

All-cause mortality is an adequate and unavoidable target in a clinical trial like ours, where we expect a mortality rate of about 50% in the control group. The question, however, remains as to what time point to use to verify a treatment effect, and how to reveal whether an improved survival from treatment can be distinguished from the high background mortality (and often wide range of serious comorbidities) in the critically ill patient with septic shock. Our study analyses mortality at 28 and 90 days.

Twenty-eight day mortality has been used as a main objective in most of the relevant trials in severe sepsis from 1991 to 2009.31 Patients with sepsis are classically considered to be patients who have a high risk of morbid complications and death. This is in large part owing to the organ dysfunction caused by sepsis, and the attendant complications of treating the organ dysfunction.32 The corollary of this situation in terms of mortality is that hospital mortality may be higher than 28-day mortality but is most likely lower than 90-day mortality.33

For this reason, analysis of mortality at 90 days has to be considered as essential to assess the clinical impact of a new therapeutic measure in septic shock treatment. Mortality with sepsis, particularly related to treating organ dysfunction, remains a priority for clinicians worldwide and deserves greater public health attention.

A source of potential weakness in the study design is the expected high mortality in the control group. We acknowledge that this can vary widely. A recent meta-analysis showed mortality rates in the control arms, ranging from 17% to 61%, which impacted the results, resulting in a benefit in the studies with the highest rates.34 We expect that our trial should be able to recruit only patients with high mortality risks based on previous patient data from our centres. We will try to meet this objective through an adequate stratification by using both severity scores and classical definitions of severe sepsis/septic shock (that by themselves have all clearly failed to this end) and dynamic parameters, that is, persistence and/or worsening signs of hypoperfusion after adequate infection source control, goal-directed fluid therapy and vasopressor infusion.

The so-called secondary objectives (average stay, time to resolution of septic shock), but with an undoubted clinical interest, should help to shape the theoretical advantages of this technique.

Why do we think we can carry out this test?

All ICUs participating in this project have extensive experience in using CRRT techniques in critically ill patients. The investigators are fully aware of the challenge of treating patients with septic shock, and have particular experience in the treatment of septic shock due to an abdominal origin (the main type of patient treated for septic shock in our centres). The high mortality of this group consumes a huge amount of resources and has generated awareness of the need for efficacy studies. This is coupled with a strong commitment from the investigators to address this issue.

In addition, our centres are fully aware of the many pitfalls associated with previous medical device trials for extracorporeal therapies. In particular, there have been many discussions centred on whether investigators and nursing staff from previous failed/negative trials were fully familiar and trained in using the technique and associated support (anticoagulation, vascular access, etc). As an example, the first large randomised CPFA trial, COMPACT I, had a complication rate of anticoagulation or other technical issues in nearly 50% of the patients.27

To overcome these hurdles, we have taken several steps to address the issue of familiarity with the technique. These include:

Practical hands-on workshops and intensive training for CPFA in each participating hospital. In these workshops, doctors and nurses have perfected their knowledge and skills in the art. In particular, we have put a lot of emphasis in including our nursing and technical professionals in the study design and execution. Clotting problems have to be taken into account in order to really be able to evaluate the efficacy of CPFA. Clotting was a major issue in the first COMPACT study.27 All investigators and staff in our study underwent a very extensive training programme for use of the machine (AMPLYA and the CPFA technique). This was one of the reasons that we had a relatively slow start for enrolment, as it was mandatory for the centre to become experienced before starting enrolment. Clotting can be due to many factors including: patient-related factors, inappropriate anticoagulation choice or lack of anticoagulation monitoring, and machine alarms/problems. We have increased awareness of all these issues. So far in our study, we have not had significant problems related to clotting.

Requirement of successful completion of at least two cycles of CPFA treatments, for patients similar to those with the inclusion requirements, before the centre will receive the authorisation to officially start the trial and have access to the randomisation portal.

Formation of an intranetwork 24/7 support group among the investigators. Investigators are able to call a core team (from the investigators’ team) to help in treatment or patient issues.

Participating centres meet on a quarterly basis to monitor trial progress and share incidents that have occurred during the study.

Dissemination

Consent or assent

The consent form acknowledges the participants will accept or decline participation in the ROMPA clinical trial. The request for the signing of this document is always a function of accredited doctors to participate in the trial.

Confidentiality

All participants’ personal information will be encrypted with the objective of keeping personal data on condition of anonymity.

Ancillary and post-trial care

Any side effects, which could have been produced while participating in the trial, can be assisted on through the specific insurance policy (HDI Hannover International, policy number 130/002/001903) related to the trial procedures.

Dissemination policy

The findings of the trial will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, as well as national and international conference presentations.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Francisco Colomina-Climent at @pacocolomina1 and Fernando Sánchez-Morán at @Fredomoran

Acknowledgements: The authors thank all the health professionals integrated in the ROMPA research group and those who will participate in our study. The copyright holder (Bellco) has approved the usage of figures 1–2.

Contributors: FC-C drafted the paper of the protocol, AP-B helped draft the paper, and the rest of the authors critically reviewed the paper before sending it to BMJ Open.

Funding: This work was supported by Bellco which provided all the devices and materials related to the use of CPFA for the treatment group and will pay the open access fee for publication in BMJ Open.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of each centre participating in the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med 2013;369:840–51. 10.1056/NEJMra1208623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Poll T, Opal SM. Host-pathogen interactions in sepsis. Lancet Infect Dis 2008;8:32–43. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70265-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bone RC, Grodzin CJ, Balk RA. Sepsis: a new hypothesis for pathogenesis of the disease process. Chest 1997;112:235–43. 10.1378/chest.112.1.235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCloskey RV, Straube RC, Sanders C et al. Treatment of septic shock with human monoclonal antibody HA-1A. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. CHESS trial study group. Ann Intern Med 1994;121:1–5. 10.7326/0003-4819-121-1-199407010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beutler B, Greenwald D, Hulmes JD et al. Identity of tumour necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin. Nature 1985;316:552–4. 10.1038/316552a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernard GR, Wheeler AP, Russell JA et al. The effects of ibuprofen on the physiology and survival of patients with sepsis. The ibuprofen in sepsis study group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:912–18. 10.1056/NEJM199703273361303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wiersinga WJ, Leopold SJ, Cranendonk DR et al. Host innate immune responses to sepsis. Virulence 2014;5:36–44. 10.4161/viru.25436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Immunosuppression in sepsis: a novel understanding of the disorder and a new therapeutic approach. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:260–8. 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70001-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaieski DF, Edwards JM, Kallan MJ et al. Benchmarking the incidence and mortality of severe sepsis in the United States. Crit Care Med 2013;41:1167–74. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827c09f8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med 2013;41:580–637. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angus DC. The search for effective therapy for sepsis: back to the drawing board? JAMA 2011;306:2614–15. 10.1001/jama.2011.1853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drewry AM, Hotchkiss RS. Sepsis: revising definitions of sepsis. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015;11:326–8. 10.1038/nrneph.2015.66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Opal SM, Dellinger RP, Vincent JL et al. The next generation of sepsis clinical trial designs: what is next after the demise of recombinant human activated protein C? Crit Care Med 2014;42:1714–21. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rimmelé T, Kellum JA. Clinical review: blood purification for sepsis. Crit Care 2011;15:205 10.1186/cc9411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Panagiotou A, Gaiao S, Cruz DN. Extracorporeal therapies in sepsis. J Intensive Care Med 2013;28:281–95. 10.1177/0885066611425759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rimmelé T, Kellum JA. High-volume hemofiltration in the intensive care unit: a blood purification therapy. Anesthesiology 2012;116:1377–87. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318256f0c0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark E, Molnar AO, Joannes-Boyau O et al. High-volume hemofiltration for septic acute kidney injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2014;18:R7 10.1186/cc13184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tetta C, Cavaillon JM, Schulze M et al. Removal of cytokines and activated complement components in an experimental model of continuous plasma filtration coupled with sorbent adsorption. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1998;13:1458–64. 10.1093/ndt/13.6.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ronco C, Brendolan A, d'Intini V et al. Coupled plasma filtration adsorption: rationale, technical development and early clinical experience. Blood Purif 2003;21:409–16. doi:73444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hassan J, Cader RA, Kong NC et al. Coupled plasma filtration adsorption (CPFA) plus continuous veno-venous haemofiltration (CVVH) versus CVVH alone as an adjunctive therapy in the treatment of sepsis. EXCLI J 2013;12:681–92. 10.1007/s00134-003-1724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abdul Cader R, Abdul Gafor H, Mohd R et al. Coupled plasma filtration and adsorption (CPFA): a single center experience. Nephrourol Mon 2013;5:891–6. 10.5812/numonthly.11904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Formica M, Olivieri C, Livigni S et al. Hemodynamic response to coupled plasmafiltration-adsorption in human septic shock. Intensive Care Med 2003;29:703–8. 10.1007/s00134-003-1724-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronco C, Brendolan A, Lonnemann G et al. A pilot study of coupled plasma filtration with adsorption in septic shock. Crit Care Med 2002;30:1250–5. 10.1097/00003246-200206000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moretti R, Scarrone S, Pizzi B et al. Coupled plasma filtration-adsorption in Weil's syndrome: case report. Minerva Anestesiol 2011;77:846–9. 10.1097/00003246-200206000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berlot G, Agbedjro A, Tomasini A et al. Effects of the volume of processed plasma on the outcome, arterial pressure and blood procalcitonin levels in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock treated with coupled plasma filtration and adsorption. Blood Purif 2014;37:146–51. 10.1159/000360268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabbri LP, Macchi A, Lecchini R et al. Post influenza vaccination Guillain-Barré syndrome. An exceptional recovery case after cardiac arrest for two hours in hyperthermia and septic shock. Anaesthesia, Pain & Intensive Care 2015;18:166–9. 10.1159/000360268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Livigni S, Bertolini G, Rossi C et al. Efficacy of coupled plasma filtration adsorption (CPFA) in patients with septic shock: a multicenter randomised controlled clinical trial. BMJ Open 2014;4:e003536 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoenberg MH, Weiss M, Radermacher P. Outcome of patients with sepsis and septic shock after ICU treatment. Langenbecks Arch Surg 1998;383:44–8. 10.1007/s004230050090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wakefield CH, Fearon KCH. Laparotomy for abdominal sepsis in the critically ill. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical treatment: evidence-based and problem-oriented. Munich: Zuckschwerdt, 2001:792–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chow S, Wang H, Shao J. Sample size calculations in clinical research. New York, NY: Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stevenson EK, Rubenstein AR, Radin GT et al. Two decades of mortality trends among patients with severe sepsis: a comparative meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2014;42:625–31. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin GS. Sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock: changes in incidence, pathogens and outcomes. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2012;10:701–6. 10.1586/eri.12.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S et al. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically Ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000–2012. JAMA 2014;311:1308–16. 10.1001/jama.2014.2637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asfar P, Claessens YE, Duranteau J, et al. , French Opinion Group in Sepsis (FrOGS) . Residual rates of mortality in patients with severe sepsis: a fatality or a new challenge? Ann Intensive Care 2013;3:27 10.1186/2110-5820-3-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]