Abstract

Objective

Knowledge about patients after calling for an ambulance is limited to subgroups, such as patients with cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, trauma and stroke, while population-based studies including all diagnoses are few. We examined the diagnostic pattern and mortality among all patients brought to hospital by ambulance after emergency calls.

Design

Registry-based cohort study.

Setting and participants

We included patients brought to hospital in an ambulance dispatched after emergency calls during 2007–2014 in the North Denmark Region (580 000 inhabitants). We reported hospital diagnosis according to the chapters of the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10), and studied death on days 1 and 30 after the call. Cohort characteristics and diagnoses were described, and the Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate mortality and 95% CIs.

Results

In total, 148 757 patients were included, mean age 52.9 (SD 24.3) years. The most frequent ICD-10 diagnosis chapters were: ‘injury and poisoning’ (30.0%), and the 2 non-specific diagnosis chapters: ‘symptoms and abnormal findings, not elsewhere classified’ (17.5%) and ‘factors influencing health status and contact with health services’ (14.1%), followed by ‘diseases of the circulatory system’ (10.6%) and ‘diseases of the respiratory system’ (6.7%). The overall 1-day mortality was 1.8% (CI 1.7% to 1.8%) and 30-day mortality 4.7% (CI 4.6% to 4.8%). ‘Diseases of the circulatory system’ had the highest 1-day mortality of 7.7% (CI 7.3% to 8.1%) accounting for 1209 deaths. After 30 days, the highest number of deaths were among circulatory diseases (2313), respiratory diseases (1148), ‘symptoms and abnormal findings, not elsewhere classified’ (1119) and ‘injury and poisoning’ (741), and 30 days mortality in percentage was 14.7%, 11.6%, 4.3% and 1.7%, respectively.

Conclusions

Patients' diagnoses from hospital stay after calling 1-1-2 in this population-based study were distributed across all ICD-10 chapters. Mortality varied widely between diagnostic groups. Non-specific diagnoses accounted for one-third of the patients and contributed to mortality in terms of total number of deaths.

Keywords: Emergency Medical Services, Ambulances, Diagnosis, Survival

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large cohort including 148 757 consecutive emergency patients brought to hospital by ambulance after calling the emergency number 1-1-2.

Population-based and registry-based study of the diagnostic pattern of the entire cohort of emergency patients brought to hospital by ambulance after a 1-1-2 call in a mixed rural–urban area.

On the basis of the Danish Civil Registration system, this study reports 1-day and 30-day mortality—total and for each International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) diagnosis chapter—for the entire group of patients brought to hospital by ambulance after a 1-1-2 call.

The main limitation of the study was that follow-up was not possible for 17.8% because patient identity was not known in the prehospital phase.

Introduction

Emergency care plays a crucial role in healthcare, both in the emergency and other departments of the hospital and in prehospital emergency medical services, and the increasing demand for emergency ambulances is a challenge in several countries.1–3 However, population-based studies on the overall diagnostic pattern and outcome for patients brought to hospital after calling for an emergency ambulance are scarce.4 The focus of research in emergency patients has mainly been on specific critical symptoms and diagnostic groups. The European Emergency Data Project defined five critical emergencies called the ‘First Hour Quintet’: cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, trauma, stroke and severe breathing difficulty requiring urgent treatment.5 6 An ambulance needs to be dispatched rapidly in case of emergencies. However, such high-risk symptoms and diagnoses may not necessarily constitute a major part of the entire prehospital emergency patient population. Thus, it is possible that the current view of the diagnostic pattern of the entire prehospital patient population, both among healthcare professionals and the public, is distorted. Population-based studies are necessary to acquire information on the full diagnostic pattern of the entire prehospital patient group.

Twenty years ago, a small prehospital population-based study including only ∼6000 patients during two short periods of 3 months in 1996 and 1997 explored the diagnostic pattern among emergency ambulance patients. The major diagnostic groups accounting for the largest number of patients were ‘injuries and poisoning’, ‘diseases of the circulatory system’ and the non-specific ‘symptoms and abnormal findings that are not classified elsewhere’. The last-mentioned group was surprisingly the third most frequent diagnosis accounting for 14.1% of the total diagnoses.7

In the North Denmark Region, one of the five Danish healthcare regions, which covers both urban and rural areas, electronic data on prehospital emergency patients have been available since spring 2006. This gave us the opportunity to conduct a large population-based study on prehospital emergency patients during the past years.

The aim of this study was to examine the diagnostic pattern and mortality in patients brought to the hospital in an ambulance dispatched after an emergency call.

Methods

Study design

We performed a registry-based follow-up study of patients brought to the hospital in an ambulance dispatched after emergency 1-1-2 calls in the North Denmark Region. The 1-1-2 call is the Danish national emergency number, common for the police, fire and emergency medical services. Data on the primary diagnoses according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10)8 were obtained, and the outcome in terms of 1-day and 30-day mortality rate together with the cumulative number of deaths was determined.

Study setting

In Denmark, healthcare, including prehospital emergency medical services, is tax-supported, with free access to ambulance services. All ambulance services operate according to contractual obligations with the healthcare regions. The North Denmark Region, with 580 000 inhabitants currently, covers both rural and urban areas. There is one regional organisation responsible for the entire emergency medical services, which includes (1) the Emergency Medical Coordination Centre that receives the 1-1-2 calls, where healthcare professionals assess the severity and need for an ambulance, (2) lay first responders, (3) the ambulance services (operated by a private company, Falck), (4) rapid response units manned by paramedics and (5) mobile emergency care units staffed by anaesthesiologists. The Danish Helicopter Emergency Services with three helicopters also covers the North Denmark Region.

Since April 2006, an electronic prehospital medical record (amPHI) has been in use in all prehospital units in this region. Data are integrated into the hospitals' electronic medical record and available for the healthcare personnel at the Emergency Medical Coordination Centre. A separate logistic electronic system (EVA 2000), which is used for the technical dispatch of prehospital resources, records time stamps and data on dispatched ambulances, first responders, mobile emergency care units and helicopters.

Study population and outcome

The study included patients with hospital contact after dispatch of ambulances due to 1-1-2 emergency calls in the North Denmark Region during the years 2007–2014. We included all 1-1-2 patients with subsequent hospital contacts, including patients with more than one 1-1-2 call during the study period. Patients attended by an ambulance but not brought to the hospital were excluded. Patient identity, level of urgency and time stamps were obtained for each dispatched ambulance after a 1-1-2 call. Each Danish citizen has a unique 10-digit civil registration number used in all Danish registries, which was used for linking data between registries. For all patients brought to a hospital in the region, we retrieved the diagnosis according to ICD-10 from the regional Patient Administrative System. We retrieved the primary diagnosis, which was the main reason for the hospital contact.8 9 In cases where a patient was examined and a diagnosis was not yet confirmed, a tentative diagnosis (observation for) an ICD-10 ‘Z-codes’ (factors influencing health status and contact with health services) may be used. In these cases, we searched for the first specific diagnosis applied during the hospital stay, including transferrals to other departments or other hospitals during the stay. These patients were then included in the study according to the first specific ICD-10 diagnosis at chapter level. For patients in whom we did not find a more specific diagnosis, we kept the Z-diagnosis as the hospital diagnosis.

We retrieved data on the vital status from the regional Patient Administrative System, in order to determine the 1-day and 30-day mortality. We defined 1-day mortality as death on the same day or the day after the 1-1-2 call, because the time of death is not registered by the hour, only by the date.

Statistical analysis

Data were anonymised for analysis. We used a dispatched ambulance that brought a patient to the hospital after the 1-1-2 call as the unit in all our analyses. Since it makes no sense to talk about diagnoses either for 1-1-2 calls or for ambulances, we named this study population ‘1-1-2 patients’, as each ambulance represents one patient. The distribution of diagnoses according to the chapters of ICD-10 was reported as the number and frequency. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate mortality rates as (1—Kaplan-Meier estimate), and these were reported as percentages with 95% CIs along with the cumulative number of deaths.

In some cases, we did not have updated information on the vital status of the patient (ie, patients with addresses outside the North Denmark Region), and these cases were censored on the day they left the hospital. We performed stratified analyses for the age groups 0–10, 11–30, 31–60 and 61 years and older. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata V.13.1 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethics

According to Danish law, the informed consent of patients is not required for registry-based studies.

Results

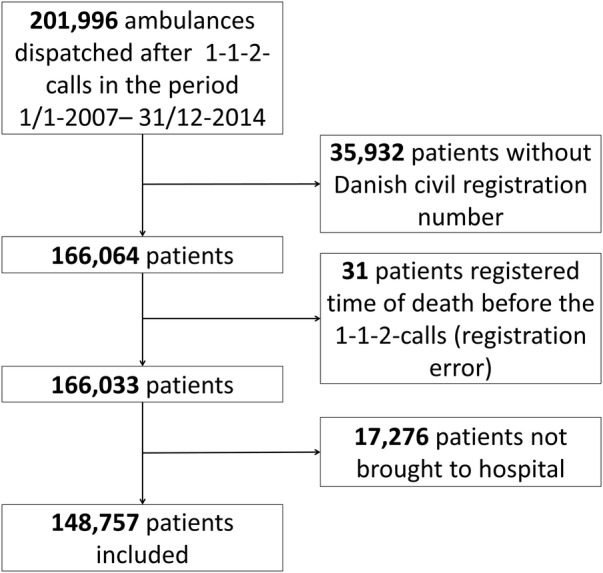

In total, 201 996 ambulances were dispatched in the period 2007–2014 after 1-1-2 calls. In 35 932 cases, the patients had no identifiable civil registration number, and in 31 cases the date of death was registered as before the 1-1-2 call. Moreover, in 17 276 cases, the patients were not brought to the hospital (including ambulances registered as not having returned to the hospital and/or patients without registered information on hospital contact). Thus, we included 148 757 ambulances dispatched to patients with subsequent hospital contact, 1-1-2 patients, as shown in figure 1, which corresponded to 97 245 individuals. Among these, 73 128 patients had only one 1-1-2 emergency call with subsequent hospital contact during the study period, while 14 449 had two and 9668 had more than two 1-1-2 calls with hospital contact during the study period.

Figure 1.

Flow chart for inclusion of patients with one or more hospital contacts after emergency ambulance dispatched after an emergency call in 2007–2014 in the North Denmark Region.

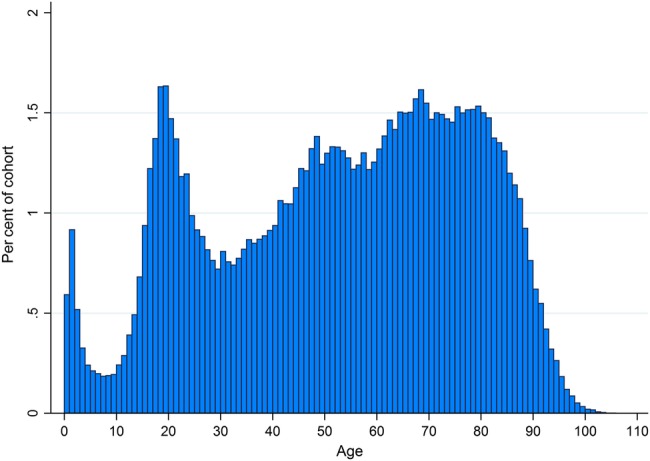

Women constituted 45.2% of the total 1-1-2 patients, and the mean age of all the patients was 52.9 years (SD 24.3), with three peaks observed: 1 year (infants), 19 years (young adults) and 68 years (elderly; figure 2).

Figure 2.

Age distribution among 1-1-2 patients with hospital contact after emergency ambulance runs (N=148 757) after an emergency call in 2007–2014 in the North Denmark Region.

Diagnostic pattern and mortality rate

The diagnostic pattern according to the chapters of ICD-10 for all 1-1-2 patients and for age groups can be seen in table 1.

Table 1.

Hospital diagnoses according to ICD-10 chapters for 148 757 patients brought to hospital after 1-1-2 call, distributed by age groups

| 0–10 years |

11–30 years |

31–60 years |

61+ years |

Total |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICD-10 chapters, age separated | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | N | Per cent | |

| I. | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 110 | 1.9 | 225 | 0.8 | 487 | 1.0 | 1229 | 1.9 | 2051 | 1.4 |

| II. | Neoplasms | 2 | 0.0 | 16 | 0.1 | 203 | 0.4 | 556 | 0.9 | 777 | 0.5 |

| III. | Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | 1 | 0.0 | 20 | 0.1 | 109 | 0.2 | 410 | 0.6 | 540 | 0.4 |

| IV. | Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 43 | 0.8 | 369 | 1.3 | 1149 | 2.3 | 1883 | 2.9 | 3444 | 2.3 |

| V. | Mental and behavioural disorders | 11 | 0.2 | 2687 | 9.1 | 4115 | 8.3 | 1246 | 1.9 | 8059 | 5.4 |

| VI. | Diseases of the nervous system | 342 | 6.0 | 933 | 3.2 | 2151 | 4.4 | 2005 | 3.1 | 5431 | 3.7 |

| VII. | Diseases of the eye and adnexa | 1 | 0.0 | 7 | 0.0 | 27 | 0.1 | 30 | 0.0 | 65 | 0.0 |

| VIII. | Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | 12 | 0.2 | 17 | 0.1 | 127 | 0.3 | 219 | 0.3 | 375 | 0.3 |

| IX. | Diseases of the circulatory system | 15 | 0.3 | 194 | 0.7 | 3717 | 7.5 | 11 836 | 18.4 | 15 762 | 10.6 |

| X. | Diseases of the respiratory system | 383 | 6.8 | 474 | 1.6 | 2081 | 4.2 | 7007 | 10.9 | 9945 | 6.7 |

| XI. | Diseases of the digestive system | 40 | 0.7 | 431 | 1.5 | 1781 | 3.6 | 2596 | 4.0 | 4848 | 3.3 |

| XII. | Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 9 | 0.2 | 45 | 0.2 | 111 | 0.2 | 92 | 0.1 | 257 | 0.2 |

| XIII. | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 14 | 0.2 | 391 | 1.3 | 1074 | 2.2 | 915 | 1.4 | 2394 | 1.6 |

| XIV. | Diseases of the genitourinary system | 18 | 0.3 | 269 | 0.9 | 589 | 1.2 | 1338 | 2.1 | 2214 | 1.5 |

| XV. | Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | 0 | 0.0 | 353 | 1.2 | 298 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 651 | 0.4 |

| XVI. | Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 47 | 0.8 | 1 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.0 | 52 | 0.0 |

| XVII. | Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 14 | 0.2 | 11 | 0.0 | 29 | 0.1 | 18 | 0.0 | 72 | 0.0 |

| XVIII. | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified | 2088 | 36.9 | 4443 | 15.1 | 8016 | 16.3 | 11 430 | 17.8 | 25 977 | 17.5 |

| XIX. | Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | 1744 | 30.8 | 13 448 | 45.8 | 15 256 | 30.9 | 14 230 | 22.1 | 44 678 | 30.0 |

| XXI. | Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | 771 | 13.6 | 4968 | 16.9 | 7894 | 16.0 | 7313 | 11.4 | 20 946 | 14.1 |

| Codes for special purposes | 0 | 0.0 | 86 | 0.3 | 104 | 0.2 | 29 | 0.0 | 219 | 0.1 | |

| Total | 5665 | 100.0 | 29 388 | 100.0 | 49 321 | 100.0 | 64 383 | 100.0 | 148 757 | 100.0 | |

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition.

The majority of the 1-1-2 emergency calls with subsequent hospital stay were among the adults older than 30 years, accounting for 76%, and those older than 60 years accounting for 43%. There were 56 193 patients in whom the first diagnosis was a non-specific Z-diagnosis, and for 35 247 of those we found and assigned a more specific diagnosis, and the patients are classified according to this. The most frequent diagnosis at the hospital was ‘injury and poisoning’, which accounted for nearly one-third of the diagnoses; this was followed by non-specific R-diagnoses (symptoms and abnormal findings not classified elsewhere) and then non-specific Z-diagnoses (factors influencing health status and contact with health services). Altogether, these three most frequent diagnoses constituted 61.6% of all the 1-1-2 calls. The fourth most frequent diagnosis was ‘diseases of the circulatory system’, followed by ‘diseases of the respiratory system’ and then ‘mental and behavioural diseases’. Injuries were the most frequent diagnosis among all age groups, except for children aged 0–10 years. Circulatory diseases was the second most frequent diagnosis among the elderly aged 61 years and above. The non-specific R-diagnosis and Z-diagnosis chapters constituted a significant fraction among all age groups, and among children (0–10 years) the R-diagnoses (chapter 18) was the most frequent.

Table 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier estimate of mortality in percentage (95% CI) and the cumulative number of deaths on days 1 and 30 for the main diagnostic chapters of ICD-10 among the 1-1-2 patients. The updated vital status was missing in 663 (0.4%) patients, and was censored in the analysis on the day they left the hospital.

Table 2.

Days 1 and 30 mortality among 148 757 patients brought to hospital after 1-1-2 call, sorted by ICD-10 chapters

| 1-day mortality | Number of deaths | 30-day mortality | Number of deaths | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapters of ICD-10 related to survival | Per cent (CI) | Day 1 | Per cent (CI) | Day 30 | |

| I. | Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 3.85 (3.10 to 4.78) | 79 | 11.17 (9.87 to 12.61) | 228 |

| II. | Neoplasms | 5.15 (3.80 to 6.95) | 40 | 31.69 (28.54 to 35.09) | 246 |

| III. | Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | 1.48 (0.74 to 2.94) | 8 | 8.7 (6.61 to 11.42) | 47 |

| IV. | Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 0.76 (0.52 to 1.11) | 26 | 4.51 (3.86 to 5.26) | 155 |

| V. | Mental and behavioural disorders | 0.06 (0.03 to 0.15) | 5 | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.04) | 66 |

| VI. | Diseases of the nervous system | 0.35 (0.22 to 0.55) | 19 | 1.7 (1.39 to 2.08) | 92 |

| VII. | Diseases of the eye and adnexa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VIII. | Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | 0.27 (0.04 to 1.89) | 1 | 1.61 (0.73 to 3.55) | 6 |

| IX. | Diseases of the circulatory system | 7.67 (7.27 to 8.10) | 1209 | 14.69 (14.15 to 15.25) | 2313 |

| X. | Diseases of the respiratory system | 2.95 (2.63 to 3.30) | 293 | 11.56 (10.94 to 12.20) | 1148 |

| XI. | Diseases of the digestive system | 1.73 (1.40 to 2.14) | 84 | 6.61 (5.94 to 7.34) | 320 |

| XII. | Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 0 | 0 | 1.95 (0.82 to 4.63) | 5 |

| XIII. | Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 0.08 (0.02 to 0.33) | 2 | 1.34 (0.95 to 1.89) | 32 |

| XIV. | Diseases of the genitourinary system | 0.77 (0.48 to 1.23) | 17 | 4.48 (3.70 to 5.43) | 99 |

| XV. | Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| XVI. | Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| XVII. | Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 1.39 (0.20 to 9.45) | 1 | 2.78 (0.70 to 10.65) | 2 |

| XVIII. | Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified | 2.38 (2.20 to 2.57) | 617 | 4.32 (4.08 to 4.58) | 1119 |

| XIX. | Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | 0.33 (0.28 to 0.39) | 147 | 1.67 (1.55 to 1.79) | 741 |

| XXI. | Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | 0.37 (0.30 to 0.47) | 78 | 1.33 (1.19 to 1.50) | 278 |

| Codes for special purposes | 1.37 (0.44 to 4.19) | 3 | 1.83 (0.69 to 4.79) | 4 | |

| Total | 1.77 (1.71 to 1.84) | 2629 | 4.66 (4.55 to 4.76) | 6901 |

International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition.

The overall mortality was 1.8% and the 30-day mortality was 4.7%. Among the 1-1-2 patients, 1-day mortality as well as the total number of deaths was the highest among those diagnosed with ‘diseases of the circulatory system’. The second highest 1-day mortality rate was reported among patients with neoplasms, but the number of deaths on day 1 was low in this group. Among patients with ‘symptoms and abnormal findings not classified elsewhere’ and ‘diseases of the respiratory system’, the number of deaths was considerably high, but the mortality rate was low.

The highest 30-day mortality, defined as 10% or higher, was reported in the ‘neoplasm’, ‘diseases of the circulatory system’, ‘diseases of the respiratory system’ and ‘infectious diseases’ groups. The diagnoses with the highest cumulative number of deaths on day 30 were ‘diseases of the circulatory system’, ‘diseases of the respiratory system’, ‘non-specific R-diagnoses’ and ‘injury and poisoning’. Mortality varied widely between age groups (see online supplementary appendix 1 for detailed tables). The highest overall 1-day mortality was among the elderly, aged 61 years or older, 3.3% corresponding to 2123 deaths, with 1-day mortality due to circulatory diseases as the highest (8.6% (CI 8.1% to 9.1%)) corresponding to 2012 deaths. In contrast, overall mortality on day 1 was 0.1% corresponding to seven deaths in the entire period among children aged 0–10 years; and 0.2%, with 68 deaths in the age group 11–30 years. Among adults aged 31–60 years, 1-day mortality was 0.9% with 431 deaths, where circulatory diseases accounted for 177 deaths, corresponding to 4.8% (CI 4.1% to 5.5%).

bmjopen-2016-011558supp_appendix.pdf (283.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

Principal findings

This population-based cohort study demonstrated that the diagnoses for 1-1-2 patients with hospital stay after 1-1-2 calls included a wide spectrum of conditions across all the chapters of ICD-10. ‘Injury and poisoning’ was the most frequent diagnosis, accounting for nearly one-third of the population. The two non-specific diagnoses in the chapters R and Z also accounted for one-third of the patients. The overall mortality varied considerably according to the diagnosis, with the highest mortality and number of deaths on day 1 reported for patients with ‘diseases of the circulatory system’. Thirty days after the 1-1-2 call, the highest number of deaths was reported among patients with circulatory diseases, but respiratory diseases as well as non-specific R-diagnoses (‘symptoms and abnormal findings not classified elsewhere’ and ‘injury and poisoning’) all contributed considerably to the number of deaths within 30 days.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

One of the major strengths of the study is the population-based design, as it covered a mixed rural–urban area that is typical of Denmark. Another major strength is the availability of data on the entire prehospital patient group for whom emergency ambulances were dispatched. The free access to healthcare, including prehospital emergency medical services, ensures that this is a genuine population-based study. The unique possiblities of linkage between registries allows for follow-up. The Danish administrative registries are regarded as very valuable tools in epidemiological research, and several validation studies have been performed.9

In order to achieve the most complete picture of the hospital diagnoses, we searched for more specific diagnoses during hospital contact in cases where the initial diagnosis was ICD-10 main Z chapter, ‘factors influencing health status and contact with health services’, which includes tentative (observation for) diagnosis for patients examined but without a diagnosis yet confirmed.

In our study, the patient's civil registration number was missing for 17.8% of the dispatched ambulances. This constitutes the major weakness of our study, as well as for many other studies on prehospital emergency medicine, because the identity of the patient is often unknown in this phase. This can be a bias in the study as these patients may be either more or less critically ill than those with a civil registration number.

Our study included patients brought to hospital by ambulance; thus, our findings cannot be generalised to prehospital emergency patients not transported to hospital.

Other studies

Within the past decade, the most frequent research topics in prehospital care are serious emergencies requiring immediate help including out-of-hospital cardiac arrest,10–12 major trauma,13 14 myocardial infarction15 and stroke.16 17 Moreover, large nationwide registries on cardiac arrest and major trauma and uniform recommendations are advantageous for research in these patient groups.10–14 Prehospital studies rarely report hospital diagnoses according to ICD-10, which is required to get a total picture of the patient group and to compare with other patients admitted to hospital. More often, the prehospital patient population is described according to the initial presented symptoms. This has also been done in a recent Danish study of 1-1-2 calls covering 75% of the Danish population showing the most frequent main symptoms, in descending order of importance, to be (1) an unclear problem, (2) chest pain/heart disease, (3) minor injuries, (4) accidents and (5) breathing difficulty.18 Thus, the most frequent symptom groups are in accordance with our study with the major hospital diagnoses being injuries, non-specific diagnoses, circulatory and respiratory diseases.

A recent Swiss population-based study from one canton described the five most frequent disease groups in their database of prehospital medical records as trauma, coma, chest pain, dyspnoea and cardiac arrest.19 This study did not report hospital diagnoses, and provided no information on non-specific diagnoses. However, this study reported a higher mortality rate of 11% after 48 hours, probably because the study included patients dead on the scene. A huge urban study from Beijing, China, available only as an abstract, showed that the top five symptoms were trauma (25.4%), general injuries (17.7%), heart problems (11.4%), loss of consciousness or fainting (10.0%) and breathing problems (8.1%).20 The symptom pattern in these studies is in accordance with our study with regard to the frequency of injuries and cardiovascular and breathing problems. The two latter studies do not inform on the rate of non-specific diagnosis, but it is not clear whether this was due to the absence of non-specific diagnoses among their patient populations or because these diagnoses were not included in their studies.

The large proportion of non-specific diagnoses found here is in agreement with the findings of a smaller Danish prehospital study conducted in 1996–1997 on patients for whom an emergency ambulance was dispatched and also a recent large cohort study on in-hospital acute medical admissions in Denmark.7 21 Our study confirms that injuries are among the most frequent diagnoses, as also found in a cohort study from a Swiss canton and a large cohort study from Beijing.19 20 It should be noted that this ICD-10 chapter covers all grades of injury, and not only major trauma, which is reflected in the low mortality rate found in this group.

Interpretation

Our study reveals that non-specific diagnoses constitute a significant part of the hospital diagnoses for prehospital emergency patients brought to hospital by ambulance. This might be due to overtriage at the Emergency Medical Coordination Centre. We cannot explain whether this overtriage is of an adequate size in order to secure ambulances to all serious emergencies, or whether it is an unnecessary large overtriage. Some of these patients might be helped better by another kind of support, and future studies are needed to explore this. Moreover, it would be of interest to study the patients' perspective. These questions require more research. Among the three age peaks noted, the elderly constituted the majority of 1-1-2 patients, and patients older than 60 years constituted 43% of all 1-1-2 patients. Veser et al3 also found that ageing was one of the demographic changes with an impact on emergency medical services. The total number of deaths among the patients with non-specific diagnoses on day 30 is remarkable and raises further questions for research. As nearly half of the patients were older than 60 years, one may hypothesise that the underlying cause for calling 1-1-2, may be acute exacerbation of chronic diseases.

This would be an interesting area for further research, as would the reasons for calling for an emergency ambulance for patients with non-specific symptoms.

The description of the diagnostic pattern in 1-1-2 emergency call with subsequent hospital stay and their prognosis may have interest for public healthcare as the prehospital system is an important part of the healthcare system. Our results may help healthcare planners, emergency physicians and prehospital caregivers. In conclusion, the diagnoses of prehospital emergency patients in this population-based study were distributed across all the ICD-10 chapters. Injuries and non-specific diagnoses accounted for nearly two-thirds of the causes in the patients. Overall mortality varied widely among the diagnoses, with high mortality noted among cardiovascular patients; moreover, non-specific diagnoses contributed to mortality in terms of the total number of deaths.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank research secretary Tim Alex Lindskou for assistance with the tables and figures and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Contributors: EFC, TML and MDB contributed to the design, analysis and drafting of the results. EMS, Region North Denmark, collected and reported the data. PAH, FB and TML extracted the data, and FBJ, TML, and MDB analysed the data. PAH, SPJ and CFC contributed to the design and drafting of the results. All authors approve of the publication of this paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: EFC is supported by a grant given from the philanthropic fund of the TRYG foundation to Aalborg University. The grant do not restrict any scientific research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Danish Data Protection Agency approved of the study (North Denmark record number 2008-58-0028 and project ID number 2015-32). According to Danish law, the informed consent of patients is not required for registry-based studies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Lowthian JA, Cameron PA, Stoelwinder JU et al. . Increasing utilisation of emergency ambulances. Aust Health Rev 2011;35:63–9. 10.1071/AH09866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowthian JA, Jolley DJ, Curtis AJ et al. . The challenges of population ageing: accelerating demand for emergency ambulance services by older patients, 1995–2015. Med J Aust 2011;194:574–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veser A, Sieber F, Groß S et al. . The demographic impact on the demand for emergency medical services in the urban and rural regions of Bavaria, 2012–2032. J Public Health 2015;23:181–8. 10.1007/s10389-015-0675-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brice JH, Garrison HG, Evans AT. Study design and outcomes in out-of-hospital emergency medicine research: a ten-year analysis. Prehosp Emerg Care 2000;4:144–50. 10.1080/10903120090941416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.GEOMED. European Emergency Data Research Network. 2006. http://www.eed-project.de/html/eed.htm (accessed 29 Dec 2015).

- 6.Fischer M, Kamp J, Garcia-Castrillo Riesgo L et al. . Comparing emergency medical service systems—a project of the European Emergency Data (EED) project. Resuscitation 2011;82:285–93. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Christenszen EF, Melchiorsen H, Kilsmark J et al. . Anesthesiologists in prehospital care make a difference to certain groups of patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 2003;47:146–52. 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2003.00042.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision. 2016. http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en (accessed 5 Feb 2016).

- 9.Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL et al. . The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol 2015;7:449–90. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wissenberg M, Lippert FK, Folke F et al. . Association of national initiatives to improve cardiac arrest management with rates of bystander intervention and patient survival after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2013;310:1377–84. 10.1001/jama.2013.278483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasselqvist-Ax I, Riva G, Herlitz J et al. . Early cardiopulmonary resuscitation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2307–15. 10.1056/NEJMoa1405796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Perkins GD, Jacobs IG, Nadkarni VM et al. . Cardiac arrest and cardiopulmonary resuscitation outcome reports: update of the Utstein Resuscitation Registry templates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a statement for healthcare professionals from a Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (American Heart Association, European Resuscitation Council, Australian and New Zealand Council on Resuscitation, Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, InterAmerican Heart Foundation, Resuscitation Council of Southern Africa, Resuscitation Council of Asia); and the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Resuscitation 2015;96:328–40. 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patel HC, Bouamra O, Woodford M et al. . Trends in head injury outcome from 1989 to 2003 and the effect of neurosurgical care: an observational study. Lancet 2005;366:1538–44. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67626-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ringdal KG, Coats TJ, Lefering R et al. . The Utstein template for uniform reporting of data following major trauma: a joint revision by SCANTEM, TARN, DGU-TR and RITG. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2008;16:7 10.1186/1757-7241-16-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montalescot G, van 't Hof AW, Lapostolle F et al. . Prehospital ticagrelor in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2014;371:1016–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1407024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fassbender K, Balucani C, Walter S et al. . Streamlining of prehospital stroke management: the golden hour. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:585–96. 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70100-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oostema JA, Nasiri M, Chassee T et al. . The quality of prehospital ischemic stroke care: compliance with guidelines and impact on in-hospital stroke response. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;23:2773–9. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.06.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen MS, Johnsen SP, Sørensen JN et al. . Implementing a nationwide criteria-based emergency medical dispatch system: a register-based follow-up study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2013;21:53 10.1186/1757-7241-21-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pittet V, Burnand B, Yersin B et al. . Trends of pre-hospital emergency medical services activity over 10 years: a population-based registry analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:380 10.1186/1472-6963-14-380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang T, Zhang J, Wang F et al. . Changes and trends of pre-hospital emergency disease spectrum in Beijing in 2003–12: a retrospective study. Lancet 2015;386:S39 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00620-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vest-Hansen B, Riis AH, Sørensen HT et al. . Acute admissions to medical departments in Denmark: diagnoses and patient characteristics. Eur J Intern Med 2014;25:639–45. 10.1016/j.ejim.2014.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-011558supp_appendix.pdf (283.6KB, pdf)