Abstract

Recent studies have suggested associations between certain genetic variants and susceptibility to persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN). The aim of the study was to evaluate the association of EDN1, NOS3, ACE and VEGFA genes with PPHN. Neonates with respiratory distress were enrolled in the study, whose gestational age ≥34 weeks, age ≤3 days. They were divided into PPHN and non-PPHN group. The EDN1, NOS3, ACE and VEGFA genes were detected by next-generation sequencing, and the results were validated by Sanger sequencing. Serum endothelin-1 (ET-1) levels were quantified by ELISA. A total of 112 neonates were enrolled (n = 55 in PPHN group; n = 57 in non-PPHN group). There is a significantly difference in the genotype distribution of EDN1 rs2070699 between the PPHN and non-PPHN group (P = 0). A higher frequency of the rs2070699 T allele was observed in the PPHN group (54.5% vs 27.2%; OR = 3.89; 95%CI 1.96–7.72). The rs2070699 T allele was associated with higher ET-1 levels (3.333 ± 2.517 pg/mL vs 1.223 ± 0.856 pg/mL; P = 0.002) and a longer ventilation period (5.8 ± 2.6 days vs 3.6 ± 3.3 days; P = 0). The results suggest there is an association between EDN1 and PPHN. The presence of the rs2070699 T allele increased the risk of PPHN in neonates with respiratory distress.

Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn (PPHN) occurs when the pulmonary vascular resistance remains elevated after birth, resulting in right to left shunting of blood through fetal circulatory pathways. This, in turn, leads to severe hypoxemia that may not respond to conventional respiratory support. The prevalence of PPHN has been estimated at 1.9 per 1000 live births1. PPHN can be easily triggered in newborns by hypoxic lung diseases such as meconium aspiration syndrome, respiratory distress syndrome, and pneumonia.

Recent studies of pulmonary hypertension in adults and neonates have increased our understanding of the genetic basis of the disease. On one hand, genes involved in the transforming growth factor-β superfamily, nitric oxide pathway, potassium channel family and endothelin system have been implicated in pulmonary arterial hypertension and/or PPHN2,3,4. On the other hand, vasoactive substances, including nitric oxide (NO), endothelin-1 (ET-1), angiotensin-II (ANG-II) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), contribute to progressive changes to pulmonary vasoreactivity via the related genes NOS3, EDN1, ACE and VEGFA5,6,7,8. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase is encoded by NOS39. Variants of this gene have been reported to be associated with coronary spasm and hypertension. ET-1 is one of the most potent and long-lasting vasoconstrictors encoded by EDN1. It plays an important role in pulmonary arterial hypertension10: increased levels of ET-1 were detected in patients with some forms of pulmonary arterial hypertension11. The association of EDN1 gene polymorphisms with hypertension and pulmonary arterial hypertension has been described12,13. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) is a key enzyme in the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) and is for the conversion of ANG-I to ANG-II in the circulation, thereby playing a crucial role in blood pressure regulation14. It has been suggested that ACE gene polymorphisms determine the phenotypic variations of enzyme levels and are associated with essential hypertension15,16,17. VEGFA encodes VEGF, a potent endothelial mitogen with angiogenic and vasoactive properties that plays a critical role in lung development18. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the association of NOS3, EDN1, ACE and VEGFA genes and PPHN.

Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Children’s Hospital of Fudan University and performed from January 2013 to January 2014. The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines.

Patients

The population of this study consisted of infants (gestational age ≥34 weeks and birth weight ≥2000 g) who were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit within 3 days of birth with clinical evidence of respiratory distress.

The inclusion criteria were: Neonates who were born at 34 weeks’ gestation or later, weighed at least 2000g at birth, aged within 3 days, and were admitted to Children’s Hospital of Fudan University with hypoxemic respiratory failure and a requirement for supplemental assisted mechanical ventilation.

The exclusion criteria were: Neonates with structural congenital heart disease excluding patent ductus arteriosus or patent foramen ovale, congenital anomalies such as congenital diaphragmatic hernia.

According to the previous study3, PPHN was diagnosed by clinical and echocardiographic data. Clinical criteria consisted of sustained partial pressures of arterial oxygen below 100 mmHg while breathing 100 percent supplemental oxygen, despite mechanical ventilation. Echocardiographic criteria included a structurally normal heart and an elevated pulmonary arterial pressure, that was considered present if there was either right-to-left or bidirectional flow across the patent ductus arteriosus or foramen ovale or a systolic pulmonary arterial pressure greater than or equal to the systemic blood pressure according to Doppler measurement of the tricuspid-regurgitation jet. Infants with respiratory distress who did not have pulmonary hypertension according to these criteria were designated as non-PPHN.

After informed consent was obtained from a parent, infants met above mentioned criteria were divided into two groups: PPHN group and non-PPHN group. Blood sample collection was completed before inhaled nitric oxide administration.

Candidate gene sequencing by next-generation sequencing (NGS)

Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood leukocytes using a QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany). The DNA concentration was measured using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Genomic DNA samples were tested by NGS sequencing using a custom-designed panel based on an AmpliSeq strategy. The panel, created using the Ion AmpliSeqTM designer software, was designed to identify disease mutations in the following genes: EDN1, ACE, VEGFA and NOS3. This design allowed for the analysis of 70 exons (EDN1: 5, ACE: 26, VEGFA: 9, NOS3: 30) (padding: + /−50 bp). The library was prepared by following the instructions provided by the manufacturers of the kits for fragmentation (Ion Shear, Life Technologies, USA), adaptor and barcode ligation (Ion Xpres Barcode Adapters Kit, Life Technologies, USA) and library quantification (Ion Library Quantification Kit, Life Technologies, USA). We used the Ion OneTouch™ system (Life Technologies, USA) to clonally amplify pooled, barcoded libraries on Ion Sphere™ particles. Torrent Suite™ software was used to compare base calls. NextGENeTM software was used to read alignments and to call variants using the human genomic reference hg19 (NCBI). The variants selected for further analysis met the following criteria: 1) the variant was detected in the sequence reads for both strands, 2) a minimum coverage of 10× was achieved, 3) the variant reads represented >20% of the sequence reads at a particular site, and 4) the targeted region covered all exons and at least 50 bp of all intron/splice sites. The filtered variants were then compared using dbSNP (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP/).

Sanger sequencing

The variants were validated by Sanger sequencing using an automated sequencer (3500XL Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems, USA).

Serum ET-1 concentration detection

Serum ET-1 levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Endothelin-1 Quantikine ELISA kit, R&D Systems, USA). Each blood sample was collected within 3 days after birth, was placed in a blank tube for 30 minutes, and was then centrifuged at 3000× g for 15 minutes. The serum was stored at −80 °C. Each step was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Sample Size and Power Calculations

We used Quanto 1.4 version (University of Southern California) to calculate the study sample size. Research is an unmatched case-control design study. According to the references, we hypothesized that 40~50% of patients would have a T allele in the baseline, chose inheritance model as Additive (GG, GT, TT) and estimated gene-environment model which would be no interaction between the PPHN and non-PPHN groups. Using a 2-sided α level of 0.05 and preinstalling 0.9976 power for gene to test the futility hypothesis in the analysis, a sample size of 55 patients in the PPHN group and 57 patients in the control group were included finally.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata version 12.0 for Windows (StataCorp). Baseline characteristics were compared between the PPHN and non-PPHN infants using the chi-square test for categorical variables and a Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon or Kruskal-Wallis rank sumtest for continuous variables. Categorical variables were summarized using frequency and rate, mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Logistic regression analyses using an α level of 0.05 were performed to determine whether gene expression increased the risk of disease occurrence. The regression imputation was based on a logistic regression model with baseline covariates for gender, gestational age, birth weight, postnatal age, maternal history of disease, and delivery mode.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the enrolled infants

In total, 112 infants were enrolled, including 55 neonates in the PPHN group and 57 neonates in the non-PPHN group. There were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the PPHN and non-PPHN group (Table 1). Among the infants in the PPHN group, the primary diagnosis were hyaline membrane disease, transient tachypnea of the newborn, perinatal asphyxia, meconium aspiration syndrome, and pneumothorax. Among the infants in the non-PPHN group, the primary diagnose were hyaline membrane disease, transient tachypnea of the newborn, perinatal asphyxia, meconium aspiration syndrome, pneumothorax and pneumonia. There was no significant difference in the primary diagnosis between the PPHN and non-PPHN group (P = 0.173) (Table 1). The maximal oxygenation-index values of the PPHN group were higher than non-PPHN group (22.335 ± 23.803 vs 6.961 ± 4.078, P = 0). Twenty-five (45.5%) required treatment with inhaled nitric oxide, 28 (50.9%) required vasoactive agents therapy, finally, 5 died of multiorgan failure (9.1%) in PPHN group. While only 1 (1.75%) required vasoactive agents therapy, and none required treatment with inhaled nitric oxide, 1 (1.75%) died finally in non-PPHN group.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the enrolled infants.

| PPHN (N = 55) | non-PPHN (N = 57) | z/χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex (%) | 31(56.36) | 36(63.16) | 0.538 | 0.463 |

| Gestational age (wk) | 37.58 ± 2.06 | 37.18 ± 2.05 | 1.197 | 0.232 |

| Birth weight (g) | 2986.1 ± 564.3 | 2880.6 ± 559.9 | 1.304 | 0.192 |

| Age at enrollment (d) | 2.4 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 0.9 | 0.782 | 0.434 |

| Cesarean section delivery (%) | 40(74.07) | 42(73.68) | 0.002 | 0.963 |

| Ventilation time (d)* | 5.4 ± 3.2 | 4.3 ± 3.9 | 3.333 | 0.001 |

| Maximal oxygenation index* | 22.335 ± 23.803 | 6.961 ± 4.078 | 6.169 | 0 |

| Inhaled nitric oxide (%)*Ψ | 25(45.5) | 0 | 33.354 | 0 |

| Vasoactive agents therapy (%)*Ψ | 528(50.91) | 1(1.75) | 35.246 | 0 |

| Mortality (%)Ψ | 5(9.1) | 1(1.75)) | 2.971 | 0.110 |

| Primary diagnosis*Ψ | ||||

| Hyaline membrane disease | 28 | 22 | 7.761 | 0.173 |

| Transient tachypnea of the newborn | 13 | 21 | ||

| Perinatal asphyxia | 9 | 8 | ||

| Meconium aspiration syndrome | 4 | 1 | ||

| Pneumothorax | 1 | 2 | ||

| Pneumonia | 0 | 3 | ||

*P < 0.05 for the comparison between groups. Ψχ2-Fisher’s Exact test.

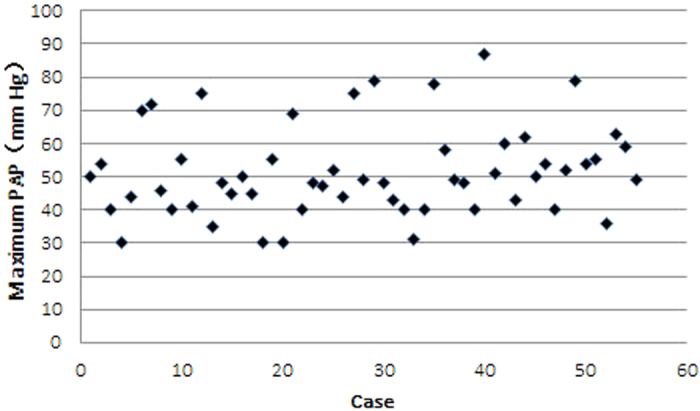

Although pulmonary artery pressure can be measured directly by Swan Ganz Catheter. There are a number of echocardiographic indicators that help indirectly to measure pulmonary artery pressure (PAP), here we use velocity of the tricuspid regurgitation (TR) jet to assess PAP. The maximum PAP trajectories of each individual patient in PPHN group are visualized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Individual values for maximum pulmonary artery pressure (PAP) in PPHN group.

Variants in candidate gene

All the enrolled neonates were evaluated by NGS on the Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine platform. Although no pathogenic mutations were identified, 48 SNPs were found (Table 2). Thirteen SNPs were found to significantly deviate from Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in non-PPHN and were therefore excluded for the further analysis. An interesting observation was that differences in the distribution of allele and genotype frequencies of rs2070699 in EDN1 were observed. A higher frequency of the rs2070699 T allele was observed in the PPHN group (OR = 3.89, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.96–7.72, P = 0) (Table 3). After adjustment for gender, gestational age, birth weight, postnatal age, maternal history of disease, and delivery mode, logistic regression analysis showed that rs2070699 T allele carriers were more likely to be PPHN than G carriers (Table 4). In order to understand the association of this genetic variation and severity of the disease, serum ET-1 levels were measured in 40 patients (n = 15 in PPHN group, n = 25 in non-PPHN group).

Table 2. SNPs identified in 112 infants by Ion Torrent sequencing.

| Gene | Chr | Nucleotide position | SNP (rs) | Nucleotide change | Minor allele frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | 17 | 61554632 | rs147912715 | G/A | 0.0028 |

| 17 | 61556298 | rs4295 | C/G | 0.3666 | |

| 17 | 61556342 | rs182340837 | A/C | 0.0022 | |

| 17 | 61556410 | rs13306087 | G/A | 0.0022 | |

| 17 | 61556429 | rs117134739 | A/G | 0.0034 | |

| 17 | 61557200 | rs4298 | C/T | 0.1444 | |

| 17 | 61557861 | rs148882466 | C/T | 0.0004 | |

| 17 | 61559923 | rs4309 | C/T | 0.4235 | |

| 17 | 61560501 | rs28730839 | C/G | 0.0004 | |

| 17 | 61560763 | rs4311 | T/C | 0.3343 | |

| 17 | 61562309 | rs4316 | C/T | 0.4808 | |

| 17 | 61562553 | rs4320 | G/A | 0.4748 | |

| 17 | 61562774 | rs4321 | T/C | 0.4702 | |

| 17 | 61564052 | rs4331 | A/G | 0.4704 | |

| 17 | 61565990 | rs4341 | G/C | 0.47 | |

| 17 | 61565998 | rs4342 | A/C | 0.47 | |

| 17 | 61566031 | rs4343 | G/A | 0.3568 | |

| 17 | 61573761 | rs4362 | T/C | 0.4125 | |

| 17 | 61574443 | rs117135474 | C/T | 0.0046 | |

| 17 | 61574492 | rs4363 | G/A | 0.4181 | |

| EDN1 | 6 | 12290732 | rs10478694 | A/- | 0.2015 |

| 6 | 12292599 | rs150035515 | G/A | 0.0026 | |

| 6 | 12292615 | rs183694577 | G/A | 0.003 | |

| 6 | 12292772 | rs2070699 | G/T | 0.3562 | |

| 6 | 12294137 | rs1800543 | T/C | 0.274 | |

| 6 | 12294258 | rs5369 | A/G | 0.0986 | |

| 6 | 12296255 | rs5370 | G/T | 0.2474 | |

| 6 | 12297028 | rs9296344 | T/C | 0.1442 | |

| NOS3 | 7 | 150696008 | rs1007311 | A/G | 0.4591 |

| 7 | 150692444 | rs1800781 | G/A | 0.1084 | |

| 7 | 150695726 | rs1549758 | T/C | 0.1823 | |

| 7 | 150696111 | rs1799983 | T/G | 0.1763 | |

| 7 | 150698879 | rs1800780 | A/G | 0.4305 | |

| 7 | 150699250 | rs1800782 | G/T | 0.127 | |

| 7 | 150704250 | rs2566514 | C/G | 0.4313 | |

| 7 | 150704400 | rs3730305 | C/A | 0.1396 | |

| 7 | 150706383 | rs753482 | C/A | 0.1857 | |

| 7 | 150706915 | rs743506 | G/A | 0.2831 | |

| 7 | 150708089 | rs891512 | A/G | 0.1116 | |

| VEGFA | 6 | 43738350 | rs2010963 | C/G | 0.3261 |

| 6 | 43738977 | rs25648 | C/T | 0.1212 | |

| 6 | 43746169 | rs3025000 | C/T | 0.2354 | |

| 6 | 43748545 | rs185218985 | G/A | 0.0008 | |

| 6 | 43748643 | rs3025052 | T/C | 0.011 | |

| 6 | 43752536 | rs3025039 | C/T | 0.1336 | |

| 6 | 43753051 | rs3025040 | C/T | 0.1512 | |

| 6 | 43753212 | rs10434 | A/G | 0.3476 | |

| 6 | 43753325 | rs3025053 | G/A | 0.0871 |

Table 3. Genotype and allele distribution of rs2070699 in 112 neonates.

| PPHN | non-PPHN | χ2 | P | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype frequency | ||||||

| GG | 12(21.8) | 30(52.6) | 11.339 | 0.001 | 0.25 | 0.11, 0.57 |

| GT | 26(47.3) | 23(40.4) | 0.545 | 0.460 | 1.33 | 0.63, 2.80 |

| TTΨ | 17(30.9) | 4(7.0) | 10.488 | 0.001 | 5.93 | 1.85, 19.03 |

| Allele frequency | ||||||

| G | 50(45.5) | 83(72.8) | ||||

| T | 60(54.5) | 31(27.2) | 31.797 | 0 | 3.89 | 1.96, 7.72 |

*The Chi-square test was used. Odds ratios and 95% CI were estimated using an additive model. As to END1 gene, the T allele of rs2070699 was more prevalent in PPHN patients compared to control subjects after Bonferroni-Dunn’s multiple comparisons post-hoc analysis for test groups (0.05/3), there revealed significant differences in frequencies of G/T alleles. CI: confidence interval.

Ψχ2-Fisher’s Exact test.

Table 4. Logistic regression analysis of risk factors associated with PPHN Risk factor.

| Factor | β-value | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | z | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs2070699 T allele | 1.358 | 3.889 | 1.96 | 7.72 | 3.88 | 0 |

| Gestational age | 0.140 | 1.150 | 0.85 | 1.56 | 0.91 | 0.365 |

| Birth weight | −0.000 | 0.999 | 0.99 | 1.00 | −0.29 | 0.769 |

| Gender | 0.658 | 1.931 | 0.75 | 5.00 | 1.35 | 0.175 |

| Postnatal age | 0.272 | 1.312 | 0.87 | 1.98 | 1.29 | 0.195 |

| Maternal history | 0.072 | 1.074 | 0.26 | 4.36 | 0.1 | 0.92 |

| Cesarean section delivery | −0.316 | 0.728 | 0.24 | 2.18 | −0.57 | 0.571 |

| Constant | −7.439 | 0.000 | 3.36E-08 | 10.28 | −1.49 | 0.136 |

R2 = 0.1737, P = 0.0013.

ET-1 concentration

In the cohort of neonates tested for ET-1, there were no significant differences in the baseline characteristics between the sequenced PPHN and non-PPHN infants; ET-1 levels were 2.794 ± 2.634 pg/mL and 2.202 ± 1.731 pg/mL, respectively (P = 0.722). The EDN1 GG genotype was associated with significantly lower ET-1 levels (P = 0.002) compared with the GT/TT genotypes. Neonates with the T allele seemed to have higher oxygenation index and longer ventilation time (Table 5).

Table 5. Comparison of the ET-1 levels between the different genotypes.

| GG (N = 15) | GT + TT (N = 25) | z/χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ET-1 (pg/ml) | 1.223 ± 0.856 | 3.333 ± 2.517 | 3.102 | 0.002 |

| Maximal oxygenation index | 6.275 ± 3.587 | 20.925 ± 23.139 | 2.900 | 0.004 |

| Ventilation time (d) | 3.6 ± 3.3 | 5.8 ± 2.6 | 3.749 | 0 |

| Mortality (%) | 0 | 3(12) | 1.946 | 0.279 |

Note: As we believe that T allele carriers were more susceptible to PPHN, infants with the GT and TT genotypes were combined into one group.

Discussion

At birth, the fetal cardiopulmonary system rapidly establishes the lung as the gas exchange organ by decreasing pulmonary vascular resistance and increasing pulmonary blood flow. Pulmonary hypertension can be easily triggered in newborns by hypoxic lung disease, apnea, or other causes. Interestingly, not all neonates requiring intensive care for respiratory failure develop PPHN1. The disease is most likely a manifestation of pulmonary vascular maladaptation precipitated by an interaction of environmental and genetic factors. A recent single-center study reported the results of the genotype analysis of 88 neonates with documented PPHN; no differences were noted in most candidate genes, including BMPR2 and nitric oxide synthase19. However, PPHN was significantly associated with genetic variants of corticotropin releasing hormone receptor-1 (CRHR1) and CRH-binding protein, as well as with significantly increased 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels.

ET was originally isolated in 1988 from the supernatant of a porcine aortic endothelial cell culture and was demonstrated to be a strong vasoconstrictive peptide20. ET has 3 isoforms (ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3) that are translated from 3 independent genes21. Although structurally and functionally similar, the expression patterns of the 3 endothelins vary considerably. ET-1 is expressed in several tissues, including endothelial cells and cardiomyocytes, whereas ET-2 and ET-3 are mainly expressed in the gastrointestinal tract and neuronal cells, respectively22. ET-1 plays a role in a variety of vascular diseases such as hypertension, arteriosclerosis, and ischemic heart disease. ET-1 levels have been examined as an important risk factor for pulmonary arterial hypertension because plasma ET-1 levels were found to be higher in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension23. DNA sequence variations in the EDN1 gene locus have been reported to be associated with blood pressure levels and idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension13,24,25.

The major objective of the present study was to investigate the association of variations of genes involved in the vasomotor reaction with the development of PPHN in patients with respiratory distress. The major findings of this study were that the rs2070699 SNP in the EDN1 is associated with a predisposition for PPHN in neonates with respiratory distress. The T allele of rs2070699 SNP may increase the risk of PPHN under respiratory distress.

In a study investigating the susceptibility to high-altitude pulmonary edema, Charu et al.26 found that the T allele of the rs2070699 SNP was overrepresented in subjects experiencing pulmonary edema. Rankinen et al.12 showed that the hypertension risk associated with rs5370 was particularly enhanced by an rs2070699 polymorphism. We found that the T allele at rs2070699 was significantly associated with an increased risk of PPHN, higher plasma levels of ET-1 and a longer ventilation time under respiratory distress. We did not find that the genetic variants of VEGFA, NOS3 and ACE significantly contributed to PPHN.

In conclusion, this study provides the first evidence of an association between the EDN1 rs2070699 SNP and the risk of PPHN in Chinese neonates with respiratory distress. However, the sample size is small; thus, the result requires confirmation in a larger sample. The role of this genetic variant in the pathogenesis of PPHN should be further investigated by functional research to provide a new theoretical basis for disease control and prevention.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Mei, M. et al. EDN1 Gene Variant is Associated with Neonatal Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension. Sci. Rep. 6, 29877; doi: 10.1038/srep29877 (2016).

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (91232712).

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.M. and G.C. finished experiment, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript. B.S., L.Y. and H.W. Acquisition of clinical data, statistical analysis. J.S. and W.Z. Conception and design, Administrative support, revising the manuscript and final approval it.

References

- Walsh-Sukys M. C., Tyson J. E., Wright L. L. et al. Persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn in the era before nitric oxide: Practice variation and outcomes. Pediatrics. 105, 14–20 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado R. D., Aldred M. A., James V. et al. Mutations of the TGF-beta type II receptor BMPR2 in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Hum Mutat. 27, 121–132 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson D. L., Dawling S., Walsh W. F. et al. Neonatal pulmonary hypertension urea cycle intermediates, nitric oxide production, and carbamoyl-phosphate synthetase function. N Engl J Med. 344, 1832–1838 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain M., Eyries M., Montani D. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies a susceptibility locus for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Genet 45, 518–521 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepke-Zaba J. & Morrell N. W. The endothelin system and its role in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). Thorax. 60, 443–444 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepke-Zaba J., Higenbottam T. W., Dinh-Xuan A. T. et al. Inhaled nitric oxide as a cause of selective pulmonary vasodilatation in pulmonary hypertension. Lancet. 338, 1173–1174 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abman S. H. Impaired vascular endothelial growth factor signaling in the pathogenesis of neonatal pulmonary vascular disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 661, 323–335 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A. M., Gruhn K., Lange S. et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE, CD143) in the regular pulmonary vasculature. Pathologe. 25, 141–146 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama M., Yasue H., Yoshimura M. et al. T-786>C mutation in the 5′-flanking region of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene is associated with coronary spasm. Circulation. 99, 2864–2870 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price L. C. & Howard L. S. Endothelin receptor antagonists for pulmonary arterial hypertension: Rationale and place in therapy. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 8, 171–185 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D. J., Levy R. D., Cernacek P. et al. Increased plasma endothelin-1 in pulmonary hypertension: Marker or mediator of disease? Ann Intern Med. 114, 464–469 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankinen T., Church T., Rice T. et al. Effect of endothelin 1 genotype on blood pressure is dependent on physical activity or fitness levels. Hypertension. 50, 1120–1125 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vadapalli S., Rani H. S., Sastry B. et al. Endothelin-1 and endothelial nitric oxide polymorphisms in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 1, 208–213 (2010). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisan D. & Carr J. Angiotensin I-converting enzyme: Genotype and disease associations. J Mol Diagn. 2, 105–115 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasyid H., Bakri S. & Yusuf I. Angiotensin-converting enzyme gene polymorphisms, blood pressure and pulse pressure in subjects with essential hypertension in a South Sulawesi Indonesian population. Acta Med Indones. 44, 280–283 (2012). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabadou I. A., Soualmia H., Jemaa R. et al. G protein beta3 subunit gene C825T and angiotensin converting enzyme gene insertion/deletion polymorphisms in hypertensive Tunisian population. Clin Lab. 59, 85–92 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Rodriguez N., Posadas-Romero C., Villarreal-Molina T. et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) gene are associated with essential hypertension and increased ACE enzyme levels in Mexican individuals. PLoS One. 8, e65700 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahm T., Crisostomo P. R., Markel T. A. et al. The critical role of vascular endothelial growth factor in pulmonary vascular remodeling after lung injury. Shock. 28, 4–14 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers H. M., Dagle J. M., Klein J. M. et al. Variations in CRHR1 are associated with persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Pediatr Res. 71, 162–167 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa M., Kurihara H., Kimura S. et al. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature. 332, 411–415 (1988). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue A., Yanagisawa M., Kimura S. et al. The human endothelin family: Three structurally and pharmacologically distinct isopeptides predicted by three separate genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86, 2863–2867 (1989). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunner F., Bras-Silva C., Cerdeira A. S. et al. Cardiovascular endothelins: Essential regulators of cardiovascular homeostasis. Pharmacol Ther. 111, 508–531 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lador F., Soccal P. M. & Sitbon O. Biomarkers for the prognosis of pulmonary arterial hypertension: Holy Grail or flying circus? J Heart Lung Transplant. 33, 341–343 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asai T., Ohkubo T., Katsuya T. et al. Endothelin-1 gene variant associates with blood pressure in obese Japanese subjects: The Ohasama Study. Hypertension. 38, 1321–1324 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J. J., Nakura J., Wu Z. et al. Association of endothelin-1 gene variant with hypertension. Hypertension. 41, 163–167 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charu R., Stobdan T., Ram R. B. et al. Susceptibility to high altitude pulmonary oedema: Role of ACE and ET-1 polymorphisms. Thorax. 61, 1011–1012 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]