Abstract

The evolution of the avian brain is of crucial importance to studies of the transition from non‐avian dinosaurs to modern birds, but very few avian fossils provide information on brain morphological development during the Mesozoic. An isolated specimen from the Cenomanian of Melovatka in Russia was described by Kurochkin and others as a fossilized brain, designated the holotype of Cerebavis cenomanica Kurochkin and Saveliev and tentatively referred to Enantiornithes. We have previously highlighted that this specimen is an incomplete skull, rendering the diagnostic characters invalid and Cerebavis cenomanica a nomen dubium. We provide here a revised diagnosis of Cerebavis cenomanica based on osteological characters, and a reconstruction of the endocranial morphology (= brain shape) based on μCT investigation of the braincase. Absence of temporal fenestrae indicates an ornithurine affinity for Cerebavis. The brain of this taxon was clearly closer to that of modern birds than to Archaeopteryx and does not represent a divergent evolutionary pathway as originally concluded by Kurochkin and others. No telencephalic wulst is present, suggesting that this advanced avian neurological feature was not recognizably developed 93 million years ago.

Keywords: bird brain, Cenomanian, Cerebavis cenomanica, endocast, neural evolution, Russia

Introduction

The evolution of avian flight has been a subject of hot debate since the discovery of Archaeopteryx some 154 years ago. However, flight‐related adaptations that are observable in the bodies of fossil and living birds provide an incomplete picture of how avian flight evolved. Fine somatic control in the inherently unstable three‐dimensional aerial environment would have been essential, so the evolution of flight capability must have been accompanied by neurosensory changes to make such control possible (Domínguez Alonso et al. 2004). Not surprisingly, volant and secondarily flightless extant birds all possess relative enlargement of brain regions that are responsible for control of balance (cerebellum) and vision (e.g. mesencephalic optic tectum, visual wulst region of the telencephalon), sensory modalities that have crucial roles in flight control. Living birds also possess large telencephala relative to other extant sauropsids, although flight control has never been demonstrated to be the main reason for this (Walsh & Milner, 2011a). In fact it has long been known that birds subjected to destruction of the telencephalon can fly and land if thrown in the air, as well as walk and avoid obstacles (Salzen & Parker, 1975).

Compared with all living sauropsids, including birds’ closest extant relatives, the crocodiles, the avian brain is large relative to body size, and is comparable to that of many mammals (Jerison, 1973). This large size appears to be mainly a result of the relative regional expansions mentioned above. Although many bird‐like theropod dinosaurs are now known to have possessed remarkably bird‐like brains in terms of relative brain region size and overall external morphology (Burnham, 2004; Osmólska, 2004; Kundrát, 2007; Balanoff et al. 2009, 2013, 2014; Norell et al. 2009), the known brain morphology of most non‐avian dinosaurs is more similar to that of living crocodiles. The timing of these changes is currently uncertain, and the occurrence of brain morphology typical of flying birds in some non‐avian bird‐like theropods that may have been capable of flight (Balanoff et al. 2013) complicates the situation somewhat.

Brains do not fossilize, but the internal surface of the brain cavity of birds does represent a reasonably accurate approximation of the external dimensions of the brain that it houses (Iwaniuk & Nelson, 2002). In fossils, sediment may fill the brain cavity after death, and where this infilling becomes lithified and is exposed through damage, information about the external shape of the original brain tissue may be revealed. These ‘endocasts’ have been the main source of data about brain morphology in fossil vertebrates since the first paleoneurological investigations of the mid‐1800s (Walsh & Knoll, 2011). Avian endocasts are nevertheless exceedingly rare in the fossil record (Walsh & Milner, 2011a) and this lack of data represented a fundamental impediment to our understanding of the evolutionary pathway by which the large relative brain size of living birds developed from the far smaller brains of their theropod dinosaur ancestors.

In the last two decades, X‐ray micro‐computed tomographic (μCT) approaches have revolutionized the field of paleoneurology by making it possible to create ‘virtual’ 3D models of brain morphology in most 3D‐preserved fossil skulls. The μCT approach also has an important advantage over analysis of isolated endocasts in that virtual endocasts reconstructed from cranial material can be linked to taxonomic identification using osteological criteria, especially where associated with postcrania. The bird‐like brain morphology known in some non‐avian theropod dinosaurs demonstrates that endocast morphology alone may be insufficient to allow referral even to higher taxa (Walsh & Milner, 2011a). There is also the possibility that analysis of isolated endocasts may lead to circular reasoning when endocast features are discussed in the context of evolutionary development, while at the same time being used for taxonomic identification. From the point of view of function‐related brain shape variation (e.g. changes in specific brain region size in relation to the evolution of flight), such changes are less informative about timing of character acquisition if not placed within a robust phylogenetic framework.

Brain morphology in Cenozoic fossil birds is steadily becoming better known thanks to an increasing sample of skulls that have not been flattened during fossilization, but brain shape in Mesozoic birds remains poorly known (Walsh & Milner, 2011a). The oldest unequivocal and most studied Mesozoic example is the partially exposed endocast of the neotype (Barrett & Milner, 2007) specimen of Archaeopteryx lithographica (NHMUK PV OR 37001). Early workers (e.g. Edinger, 1926; de Beer, 1954) regarded this endocast as reptilian rather than avian in form and volume, but this view was later challenged by Jerison (1968) and, most recently, by Domínguez Alonso et al. (2004) based on μCT analysis. Balanoff et al. (2013) reanalyzed this μCT dataset and suggested that Archaeopteryx may have possessed a feature of the telencephalon called a ‘wulst’, a feature that is effectively a synapomorphy of Neornithes (Walsh & Milner, 2011b). The significance of this structure will be discussed later.

Reconstructions of the brains of the Late Cretaceous ornithurine toothed birds Ichthyornis victor (Ichthyornithiformes) and Hesperornis regalis (Hesperornithiformes) were given by Marsh (1880), but this material was subsequently shown by Edinger (1951) to be too incomplete to provide much evidence of brain shape. Elzanowski & Galton (1991) described the inside of the braincase of another ornithurine, Enaliornis barretti (Hesperornithiformes), from the Early Cretaceous of England, but the incomplete nature of both examined specimens meant that only limited information about the caudal‐most regions was available. Chatterjee (1991) described a composite endocast from the Triassic Protoavis texensis, but as this taxon is not widely accepted as being closely related to birds (Witmer, 2002), information from the endocast is of uncertain value. Over the past few decades, Chinese Mesozoic deposits have yielded an excellent avian fossil record that has provided a great deal of information about adaptation and paleoecology in archaic avian lineages (Zhou & Zhang, 2007). However, μCT scanning to determine brain morphology is not viable in these fossils because of their generally flattened preservation. Consequently, Archaeopteryx remains the only Mesozoic bird for which brain shape is completely known. Ornithurine brain shape is incompletely known from fragmentary evidence, and virtually nothing is known about brain shape in extinct archaic lineages such as Enantiornithes.

One specimen that may provide useful information about enantiornithine neurosensory development comes from the Middle Cenomanian of the Volgograd region of Russia. This isolated specimen was described by Kurochkin et al. (2006, 2007) as a ‘fossil brain’, and is potentially very important for studies of avian brain evolution because it is preserved in three dimensions and comes from a period where nothing is known about the degree of neural adaptation and development in any avian lineage. These authors performed μCT analysis of the specimen and concluded that its shape differs markedly from that of any known avian brain, living or fossil, and that neural development in this taxon followed a divergent evolutionary path from other fossil avian clades in which brain development is known. Based on these differences, Kurochkin et al. (2006) proposed a new genus and species for this specimen, Cerebavis cenomanica, and tentatively referred C. cenomanica to the archaic avian clade Enantiornithes.

Although this specimen can potentially provide crucial data about avian brain evolution during the Late Cretaceous, we have already noted (Walsh & Milner, 2011a) that the tomographic data published by Kurochkin et al. (2006) show this specimen to be an incomplete and abraded skull rather than a preserved brain or even an endocast. We provide here an alternative description of the endocast morphology derived from the full μCT dataset kindly provided by Evgeny Kurochkin to one of us (E Bourdon), as well as a description of the endosseous inner ear and endobasicranial cavities (including the pharyngotympanic connections).

Institutional abbreviations

MNHN, Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle, Paris; PIN, Paleontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow; NHMUK, The Natural History Museum, London.

Cerebavis cenomanica: discovery, geological context and history of analysis

The holotype and only specimen of Cerebavis cenomanica (PIN 5028/2; Fig. 1A) was stated to measure 20.6 mm in length, 13.6 mm in width and 13.7 mm in depth, with an estimated volume of 1.0 cm3 (Kurochkin et al. 2006). The specimen was recovered in 1993 from a phosphate‐rich level of the Melovatskaya Formation in the Zhirnovskii District of the Volgograd Region of Russia, dated as Middle Cenomanian based on mollusc and chondrichthyan fossils (Kurochkin et al. 2006). In addition to the chondrichthyan fauna, other vertebrate taxa found in the phosphorites include actinopterygians, ichthyopterygians and sauropterygians, with rare fragments of pterosaurs and birds. Invertebrate fossils are mostly preserved as steinkerns and include bivalves, brachiopods, rare cephalopods and sponges (Kurochkin et al. 2006).

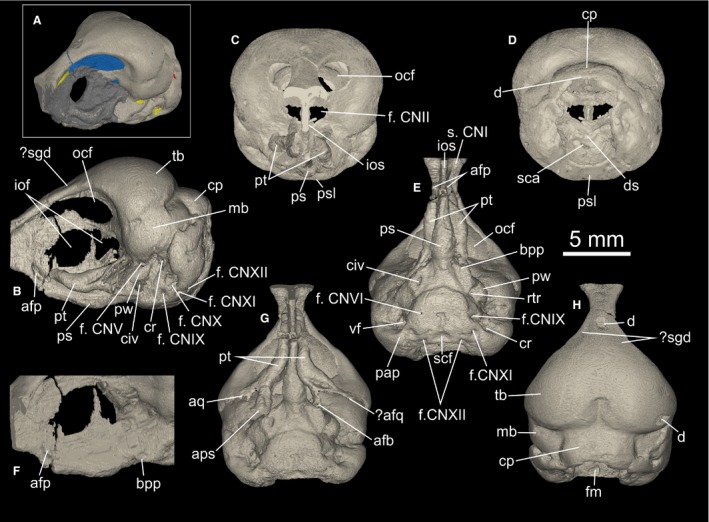

Figure 1.

μCT visualization of the holotype skull of Cerebavis cenomanica. (A). Three‐quarter left lateral view of the skull showing segmented endocast (blue), cranial nerves (yellow) and vascular openings (red), with matrix covering shown in mid gray. (B) Skull in left lateral, (C) rostral, (D) caudal, (E,G) ventral and (H) dorsal views. (F) Detail of the two buttresses mentioned in the text in left lateral view. afb, articular facet for basipterygoid process; afp, articular facet for pterygoid; afq, articular facet for quadrate; bpp, basipterygoid process; cp, cerebellar prominence; cr, columellar recess; d, damage; ds, dorsum sellae; f.CNII, foramen for the optic nerve; f. CNV, foramen for the trigeminal nerve; f. CNVII, foramen for the facial nerve; f. CNIX‐XI, foramen for the undifferentiated glossopharyngeal, vagus and accessory nerves; f. CNXII, foramen for the hypoglossal nerve; fm, foramen magnum; iof, interorbital fonticulus; ios, interorbital septum; mb, mesencephalic bulge; ocf, orbitocranial fonticulus; pap, paroccipital process; ps, bulge in the parasphenoid rostrum; psl, parasphenoid lamina; pt, pterygoid; pw, parasphenoid wing; rcc, rostral end of cranial carotid canal; rtr, rotral tympanic recess (Fig. 3); sca, sulcus for the cranial carotid arteries; scf, subcondylar fossa; s. CNI, sulcus for the olfactory nerve; tb, telencephalic bulge.

Chemical analysis using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) techniques indicated the specimen comprises calcium as the main constituent (40–50%), with silica (20–35%) and phosphorus (15–20%) as the remaining main components. Kurochkin et al. (2006) suggested that rapid phosphatization in water saturated with silica and phosphorus was responsible for preservation of the soft tissue brain structures. They also suggested that the reason the ‘brain’ structures had survived at the expense of the surrounding calcium phosphate skull material was because the silica content of the preserved ‘brain’ made it more resistant to erosion compared with the phosphatic bone.

μCT analysis

Kurochkin et al. (2006) noted that PIN 5028/2 was initially mistaken for an avian skull but that it was difficult to distinguish bony structures such as the interorbital septum and parasphenoid from the phosphatized material of the rest of the specimen. This confusion was ostensibly resolved when the specimen was scanned using μCT analysis, which led the authors to conclude that, apart from the bony structures already recognized, the whole specimen was a fossilized brain. The results of the μCT analysis were included only in Kurochkin et al. (2006) and were not mentioned in a subsequent paper (Kurochkin et al. 2007).

PIN 5028/2 was scanned using a Skyscan 1072 at the University of Antwerp, Belgium. Kurochkin et al. (2006) recorded a range of scanning energies – 40–80 kV and 300–400 mA – suggesting more than one scan was made, but it is not possible to determine which energies were used for the published dataset. No filtering was noted, but these parameters are nevertheless unimportant for interpreting the dataset. The resulting slice stack comprised 1022 slices (443 × 439 pixel grid) saved as 8‐bit data. The image stack does not include a small (~2 mm) rostral‐most portion of the frontals. Kurochkin et al. (2006) state a resolution of 6 μm for the dataset, but this is clearly incorrect as the widest point of the specimen measures 384 pixels, equating to 2.3 mm at 6 μm rather than the published measurement of 13.6 mm. Using those measurements to calculate the true resolution gives an isotropic voxel value of 35 μm.

Original diagnosis of Cerebavis cenomanica

Cerebavis cenomanica Kurochkin et al. (2006) was diagnosed by the following characters (terms in parentheses represent our revised interpretation): cerebral hemispheres (skull roof) rounded oval; olfactory tracts thick, with large olfactory bulbs (rostral portion of frontals); inter‐hemispheric fissure shallow (external expression of interhemispheric fissure); parietal organ (external expression of inter‐hemispheric notch) well pronounced and located in pineal recess on the caudal slope of the inter‐hemispheric fissure; roof of midbrain with large auditory tubercles (lateral margins of cerebellar prominence); well developed epiphysis located between auditory tubercles (cerebellar prominence); optic tubercles (external expression of the mesencephalon) located caudoventral to cerebral hemispheres, not projecting laterally beyond them; middle part of parasphenoid rostrum swollen.

Revised description of the cranial osteology of Cerebavis cenomanica

Anatomical nomenclature follows Baumel & Witmer (1993) with English equivalents of Latin terms. Reinterpreted as a skull, PIN 5028/2 (Fig. 1A–H) is clearly damaged and incomplete. Its dorsal surface is polished and small sections of bone are missing from the frontal and parietal regions, revealing the matrix infilling of the brain cavity. Although this damage reveals the bone wall to be thin, its uniformity (based on μCT analysis) and absence of deep abrasion‐related scratches strongly suggests the bone missing in this region is not significant. However, more severe attritional damage and rounding through abrasion is apparent in the caudal region of the skull (see below). This pattern of attrition and abrasion is typical of reworked bone material in other phosphorite bone accumulations (Walsh & Martill, 2006; Boessenecker et al. 2014), suggesting the specimen was reworked prior to redeposition in a phosphatic lag deposit.

The frontals are truncated rostrally by a fracture line, which is rounded by post‐fossilization abrasion (not visible in Fig. 1 because the scan data do not extend this far rostrally). This break is situated close to where the craniofacial flexion zone would be expected. However, the dorsal surface of the frontal is very slightly concave in this area (Fig. 1C,H), suggesting that if a kinetic boundary was present, the fracture surface is some way caudal to it. No inter‐frontal suture is detectable on the skull surface or in the μCT tomographs. The frontal is exceedingly narrow in the interorbital region (Fig. 1E,H), and the roof of the orbit lacks a median groove. A small depression is present on the dorsal edge of the frontal, where the bone begins to widen towards the caudal wall of the orbit (Fig. 1B,H). These paired depressions may represent minute salt gland depressions, the presence of which would be unsurprising considering the marine paleoenvironment in which the specimen was found (Kurochkin et al. 2006).

The ectethmoid is poorly developed to absent. The dorsal lamina of the mesethmoid is narrow and lacks a depression for the caudal concha. Lacrimals are not preserved, suggesting the lacrimal was most probably not fused to the frontal bone. There is no obvious facet on the lateral edge of the frontal for contact with the lacrimal, but this may have been lost by abrasion.

The orbital region is covered by matrix, but μCT analysis reveals the interorbital septum is perforated by an oval interorbital fonticulus situated roughly in the center of the septum (Fig. 1B,F). The interorbital fonticulus is divided by a narrow, dorsally projecting spur of bone that does not appear to connect with the roof of the orbit. A pair of large orbitocranial fonticuli perforate the caudal wall of the orbit. These extend as far as the rostral extent of the skull reconstruction, so the ventrolateral floor of each foramen for the paired olfactory nerve (CNI) bundles was not ossified. The foramen for the optic nerve (CNII) and associated blood vessels was also not fully ossified and conforms to the Type 3 foramen form of Hall et al. (2009).

The vault of the cranium that houses the telencephalon is broadly rounded and devoid of a marked eminence on either side. A cerebellar prominence (external expression of the cerebellar fossa) is present and very broad, but is only partially preserved. There is no evidence of a sagittal nuchal crest (Fig. 1H). The junction between the frontals and parietals presumably occurs along the angle between the convexity of the cranial vault and cerebellar prominence, but no frontoparietal or interparietal sutures are visible on the skull surface or in the μCT tomographs. The whole lateral surface of each parietal represents a rounded bulge that would have housed each lateral expression of the mesencephalon. The temporal region is similar to that of modern birds, which have lost the typical diapsid condition. The bar between the upper temporal and lower temporal fenestrae has disappeared in Cerebavis, ostensibly indicating that a postorbital bone was absent. However, skull roof element homology is obviously difficult to establish with certainty without visible suture patterns. No postorbital process or temporal crest is apparent in the temporal region (Fig. 1B,D), but absence of these structures might be due to attrition and abrasion. Likewise, no transverse nuchal crest is apparent in the occipital region, and this also may be missing due to abrasion.

The paroccipital process is very poorly developed, and there is no conspicuous bony ridge (lateral parasphenoid process) connecting the ventral border of the process with the lateral edge of the parasphenoid lamina (Fig. 1E). Again, this may be due to abrasion. The lateral and ventral walls of the foramen magnum are preserved, but the dorsal margin is damaged, making the foramen appear dorsoventrally elongate. The remaining border of the foramen magnum appears to show that it was circular, and steeply angled relative to the parasphenoid lamina (i.e. only slightly ventrally oriented). The occipital condyle is not preserved, but a fossa interpreted to be the subcondylar fossa is present (Fig. 1E). Together with the position of the foramina for the hypoglossal nerve (CNXII), this evidence indicates that the missing caudal region of the skull is relatively small and mostly located dorsal to the foramen magnum.

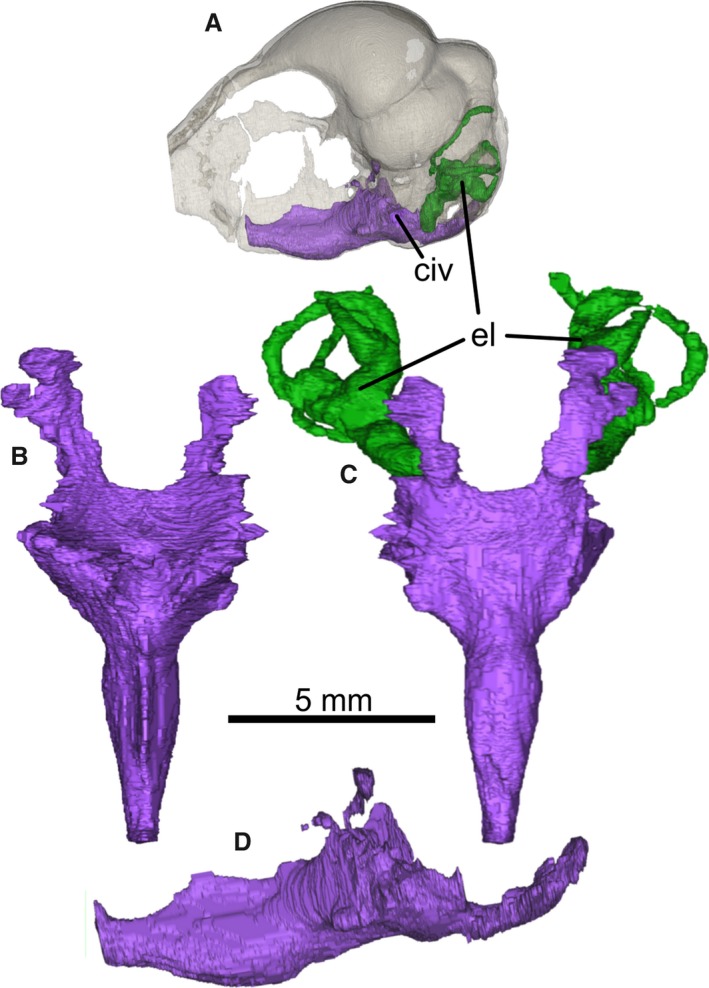

The parasphenoid lamina is a rounded square shape in ventral view (Fig. 1E), and somewhat ventrally projected such that it lies distinctly ventral to the parasphenoid rostrum. A parabasal fossa (sensu Baumel & Witmer, 1993: p. 81) of the kind found in most modern birds was apparently absent. Medial parasphenoid processes (basal tubercles) are absent or very poorly developed, but this may also be due to abrasion. The pharyngotympanic (Eustachian) tubes are visible in the μCT data but are difficult to trace over their entire extent (Fig. 2). They project rostrally from the tympanic cavity, but join a large vacuity within the parasphenoid rostrum, interpreted here as the rostral tympanic recess. Tracing the path of the pharyngotympanic tubes is not possible after they meet the main cavity of the rostral tympanic recess. The endobasicranial cavity communicates with the lateral surface of the brain cavity floor (Fig. 1A), but not the ventral surface of the parasphenoid lamina. Consequently, the pharyngotympanic tubes must have opened laterally, as in paleognaths, but not neognaths in which they open close to the midline of the parasphenoid lamina (Cracraft, 1988).

Figure 2.

Endosphenoidal cavity network segmented from PIN 5028/2. (A) Skull rendered transparent to show the position of the cavity network; cavity network endocast in (B) dorsal, (C) ventral and (D) left lateral views. (C) Relationship of the cavity network to the endosseous inner ear labyrinths and the shape of the caudally oriented pharyngotympanic tubes. civ, external communication with endoparasphenoid cavity network; el, endosseous inner ear labyrinth. Note that the network will have comprised pneumatic and vascular structures in life that are difficult to differentiate in these data.

The parasphenoid wing is poorly developed (Fig. 1B,E). A small opening of the rostral tympanic recess lies medial to the parasphenoid wing (Fig. 1B,E). There are poorly developed dorsoventrally compressed basipterygoid processes at the base of the parasphenoid rostrum, for articulation with the pterygoid (Fig. 1E,F). The basipterygoid processes are smaller than in paleognathous birds including tinamous, ratites and lithornithids (e.g. Pycraft, 1900; McDowell, 1948; Bock, 1963; Houde, 1988; Bertelli et al. 2014). The parasphenoid rostrum itself is long, stout, wide at its stepped junction with the parasphenoid lamina, and shows a conspicuous lateral and ventral expansion around its midpoint (Fig. 1E). From this point the parasphenoid rostrum continues to taper rostrally, with the ventral margin angled dorsally in lateral view (Fig. 1B). Marked buttresses are present on either side of the parasphenoid rostrum at the level of the rostral‐most extent of the interorbital fonticulus (Fig. 1F; see below). These might correspond to the articular facet with the rostral end of the pterygoid.

The middle ear region is heavily abraded, but μCT visualization reveals that no columella is preserved. The shallow columellar recess is visible on both sides (Fig. 1B,E), but abrasion prevents determination of further details. The cotylae for articulation with the quadrate are not preserved.

The foramen for the trigeminal nerve (CNV) is rostral to the parasphenoid wing, as in most modern birds, and in contrast to Enaliornis, Hesperornis, Phaethontiformes, Fregatidae and some Procellariiformes (Elzanowski, 1991; Elzanowski & Galton, 1991; Bourdon et al. 2005). The foramen is not split, so the separation of the three trigeminal branches (CNV1–3) must have occurred after the exit of the nerve from the lateral skull wall. The foramen for the facial nerve (CNVII) possibly exits the brain cavity caudal to the foramen for the trigeminal nerve and dorsal to the columellar recess (Fig. 1B). Paired foramina for the abducens nerve (CNVI) are present on the ventral surface of the lamina, and for the hypoglossal (CNXII) on its caudoventral surface, just lateral to the subcondylar fossa (Fig. 1E). Two foramina are present on the left caudolateral surface that correspond to the bundle that includes the glossopharyngeal (CNIX) and vagus (CNX) nerves. Another foramen is present in a more caudoventral position that is interpreted to be the accessory (CNXI) nerve, as it branches from the same bundle as CNIX and CNX. However, the situation on the right hand side is less clear in this scan dataset, and only the main openings for CNX and CNXI are definitely detectable. In Enaliornis, Hesperornis and a few neornithine birds including Phaethontiformes and some Procellariiformes, the foramen for the vagus nerve (CNX) is in a marginal position, and a separate foramen for the glossopharyngeal nerve (CNIX) is absent (Elzanowski, 1991; Elzanowski & Galton, 1991; Bourdon et al. 2005).

The external ophthalmic blood vessels leave the brain cavity via small foramina located in the angle between the convexities that house the telencephalon and mesencephalon. The cranial carotid arteries are only housed in bony tubes close to where they converge and enter the pituitary fossa. A foramen for the entrance of the cranial carotid artery into the middle ear cavity is absent. The arteries were not enclosed in a bony canal while crossing the middle ear cavity, and they must have extended through the endobasicranial cavity after entering the skull. Due to this, their entry point into the skull cannot be determined with certainty.

A pair of elongate structures covered by matrix extend along the dorsal wall of the parasphenoid rostrum (Fig. 1B,E). μCT visualization indicates that these structures are pterygoids, but the exact morphology of these elements is difficult to determine because of poor contrast between the bone and matrix. Because of this, the surface closest to the interorbital septum cannot be traced with certainty, but the elements do appear to have been hollow with relatively thin bone walls. Each pterygoid is rod‐like and sigmoidal in form. At their caudal extent the pterygoids widen and bifurcate to form two processes, the ventral‐most of which remains in contact with the basipterygoid process of the parasphenoid rostrum on both sides (Fig. 1F). This contact does not appear to be an artifact of preservation. The second process projects dorsally but does not connect with the braincase. We tentatively interpret the tip of this process as the articular facet for the quadrate (Fig. 1G). The pterygoids are long enough to have reached the rostral parasphenoid rostrum buttresses (Fig. 1F), but their rostral‐most extent is situated dorsal to the structure. It seems likely that the rostral articulation of the pterygoids included the parasphenoid rostrum as well as the palatine itself, and that the elements were displaced dorsally and rotated medially prior to fossilization. An interpretation of their original position and orientation is shown in Fig. 1G. As no part of the vomer or palatines is preserved in this specimen, these elements must have been lost before the skull was fossilized.

Emended diagnosis of Cerebavis cenomanica based on external skull morphology

Our diagnosis uses only osteological characters that can be observed without the use of μCT analysis.

All skull roof cranial sutures obliterated; frontals exceedingly narrow in interorbital region (possible autapomorphy); small depressions present on dorsolateral edge of frontals in caudal region of orbit roof (possible autapomorphy); cerebellar prominence present and very wide; paroccipital processes very poorly developed; foramen for cranial carotid artery absent; parasphenoid lamina approximately square and projects ventrally beyond the parasphenoid rostrum (possible autapomorphy); presence of small, dorsoventrally compressed basipterygoid processes at the base of the parasphenoid rostrum (the peculiar shape of the processes might be autapomorphic); parasphenoid rostrum stout with conspicuous expansion at midpoint (possible autapomorphy); large orbitocranial fonticuli extending rostrally to olfactory nerve sulcus; optic nerve foramen Type 3 (sensu Hall et al. 2009); foramen for trigeminal nerve slightly rostral to parasphenoid wing; ectethmoid poorly developed to absent; pterygoids rod‐like, sigmoidal and possessing two distinct caudal processes (possible autapomorphy).

Revised description of the brain morphology of Cerebavis cenomanica

Reconstruction of the brain cavity endocast and endosseus inner‐ear labyrinths was conducted using materialise mimics 17.0. The dorsal skull roof bones are very thin (< 100 μm in places) and, as mentioned above, there is a close relationship between the brain cavity endocast and the external morphology of the skull. Consequently, a good estimation of dorsal brain shape is possible using external skull morphology as a guide, and the brain morphology description given by Kurochkin et al. (2006, 2007) is in some instances close to that of our reconstructions (Fig. 3A–E). For conciseness, neuroanatomical descriptions of the endocast given below use standard Anglicized neuroanatomical nomenclature. It should, however, be noted that these terms relate to osteological brain cavity correlates of the original gross external neural anatomy, and should therefore be regarded as interpretative. Measurements of morphological features are given in Table 1.

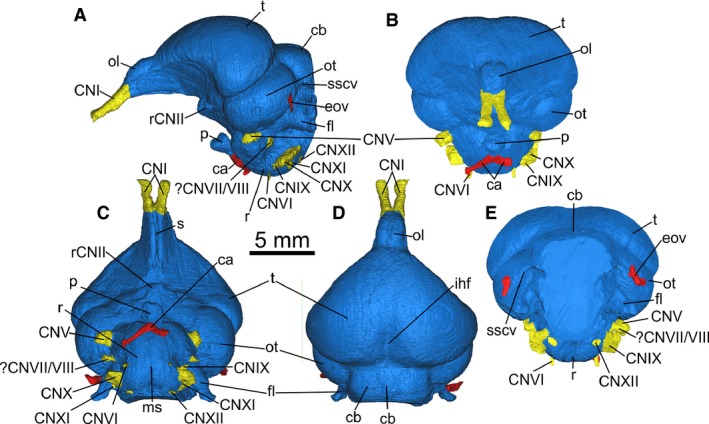

Figure 3.

Endocast segmented from PIN 5028/2 in (A) left lateral, (B) rostral, (C) ventral, (D) dorsal and (E) caudal views. ca, carotid arteries; cb, cerebellum; CNI, olfactory nerve; CNV, trigeminal nerve; CNVII/VIII, facial and vestibulocochlear nerve (undifferentiated); CNVI, abducens nerve; CNIX‐X, bundle including the glossopharyngeal, vagus and accessory nerves; CNXII, hypoglossal nerve; eov, external occipital vein; fl, cerebellar flocculus; ihf, interhemispheric fissure; ms, median sulcus; ol, olfactory lobe; os, occipital sinus; ot, optic tectum; p, pituitary; r, rhombencephalon; rCNII, root of the optic nerve; s, sulcus; sscv, impression of the semicircular vein; t, telencephalon. Identification of CNIX‐XI is tentative. Note that the nomenclature used here refers to interpretation of osteological correlates of external neuroanatomy and vasculature rather than certain identification of those structures.

Table 1.

Linear measurements (in mm) of the maximal dimensions of main brain regions of the endocast of Cerebavis cenomanica

| Region | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Telencephalon (including olfactory lobes) length | 11.75 |

| Telencephalon width | 13.1 |

| Telencephalon height | 5.82 |

| Olfactory lobe length | 3.76 |

| Olfactory lobe width | 2.19 |

| Olfactory lobe height | 3.72 |

| Optic tectum length | 5.89 |

| Optic tectum height | 3.95 |

| Cerebellum length (as preserved) | 3.18 |

| Cerebellum width | 6.34 |

| Cerebellar flocculus length | 3.62 |

Overall, the endocast morphology of Cerebavis is remarkably similar to that of many living species. For instance, when viewed laterally (Fig. 3A) the endocast displays a strong flexure of the main brain axis, similar to most smaller extant neornithine taxa, particularly those possessing especially large eyes (Portmann & Stingelin, 1961; Kawabe et al. 2013) or acute angular relationships between the bill and main skull axis as in parrots and sandpipers (Portmann & Stingelin, 1961; SA Walsh, pers. obs.). As such, the telencephalon, mesencephalon and rhombencephalon appear stacked above each other in lateral view. As a result of this and the width of the telencephalon relative to that of the optic tectum (see below), the telencephalon also completely occludes the mesencephalon in dorsal view (Fig. 3D).

Telencephalon

Casts of blood vessels and defined sinuses are absent on the telencephalon. In dorsal view (Fig. 3D) the telencephalon is broader than long, lacks a defined interhemispheric fissure rostrally, and displays only a shallow interhemispheric sulcus within its caudal‐most half. The broadest part of the telencephalon occurs within that caudal region, resulting in a cordiform outline in dorsal view, much as in the majority of living birds (Walsh & Milner, 2011a). At this point the rostral‐facing surface of the lateral margin of the telencephalon is slightly expanded rostrally, forming a slight notch in lateral view (Fig. 3A). Evidence of a wulst (a distinct swelling on the dorsal surface of the telencephalon; see Walsh & Milner, 2011a for discussion) development is absent.

The olfactory nerves (CNI) bifurcate strongly at the rostral‐most margin of the olfactory lobes (Fig. 3B–D). The olfactory lobes themselves are large (Table 1) and proportionately larger than in Archaeopteryx regardless of whether the area interpreted by Domínguez Alonso et al. (2004) as the olfactory tract is included as part of the olfactory lobe (sensu Balanoff et al. 2013) or not. The endocast of Cerebavis exhibits a defined notch on the dorsal surface that demarcates the olfactory lobe from the rest of the telencephalon, although this cannot be followed laterally due to absence of ossification in this region (Fig. 3A–D). The dorsal surface of the olfactory lobe region bears a very shallow inter‐lobe sulcus (Fig. 3D), with a deep and narrow sulcus on the ventral surface (Fig. 3C).

Mesencephalon

The mesencephalic tegmentum is unlikely to have been exposed due to the lateral expansion of the telencephalon and brain axis flexure, so visible regions of the mesencephalon probably comprise the optic tectum and semicircular torus. These visible regions (mostly optic tectum) are a dorsoventrally flattened oval shape in lateral view (Fig. 3A), and are relatively large compared with most living avian taxa. The ventral surface of the mesencephalon exhibits a broad semicircular vein cast that extends onto the lateral surface of the cerebellum up to where the skull is damaged (Fig. 3A,E), indicating that the vein was not enclosed in a bony tunnel at any point. The inner ear labyrinth is situated within the lateral wall of the cerebellar fossa rather than the caudal wall of the mesencephalic fossa.

Diencephalon

As in extant birds, the pineal gland has apparently left no impression on the skull roof (Fig. 3D). The exit of the optic nerves and optic chiasma are not possible to determine as a result of incomplete ossification in this region (Type 3 CNII foramen of Hall et al. 2009). The pituitary is relatively small, polyhedral and is rotated dorsally at its junction with the main endocast, such that it projects rostrally rather than ventrally (Fig. 3A–C). This condition is unlike that seen in any extant or fossil bird we have so far examined.

Cerebellum

The caudal‐most region of the cerebellum is missing on the reconstructed endocast due to damage around the foramen magnum. The reconstruction of the remaining cerebellum shows that it was broad (Fig. 3D), and although its caudal‐most extent is not possible to determine, the position of the cerebellar flocculi (Fig. 3A,C,D), preservation of CN XII on the medulla (Fig. 3C) and caudal extent of the occipital sinus cast (Fig. 3D) suggests that little is missing. The region was probably rostro‐caudally short and oriented vertically. Cerebellar folliae are not impressed on the cerebellar fossa, although a relatively shallow and narrow occipital sinus is evident on the endocast (Fig. 3D). The flocculi are large, slightly rostrocaudally compressed and directed caudally. As such they conform well to the Type 5 flocculus form of Walsh et al. (2013).

Medulla

In ventral view the medulla is almost spherical and bears a shallow sulcus on the ventral surface. The form and development of the cranial nerves is difficult to resolve in this dataset. The oculomotor (CN III) and trochlear (CN IV) nerves are not possible to reconstruct. The trigeminal nerve (CN V; Fig. 3A,C,E) is large but appears somewhat underdeveloped relative to living birds, and the three main branches (CN V1–3) are difficult to distinguish with certainty. The short distance between their origin on the ventral edge of the optic tectum and external surface of the skull suggests the branches did not separate until the nerve emerged from its foramen. The abducens nerve (CN VI; Fig. 3C) is very narrow and cannot be traced far after its exit from the medullar fossa. The vestibular and cochlear branches of the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII) are not possible to trace in this dataset. However, the facial nerve (CN VII) is unusually thick (Fig. 3A,C), and since birds virtually lack any facial musculature it may be that part of CN VIII is included in the foramen for CN VII. The glossopharyngeal (CN IX) vagus (CN X) and accessory (CN XI) nerves appear to differentiate before leaving the skull, but the shape of the nerve bundle (dorsoventrally compressed) makes identification of each nerve problematic. The hypoglossal (CN XII) nerve is present and narrow.

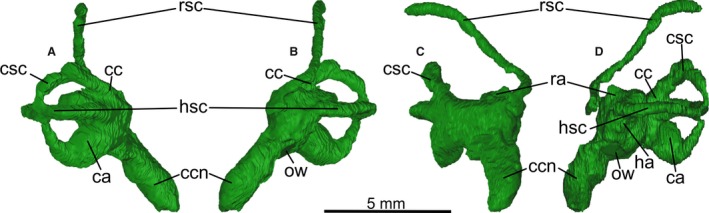

Endosseus inner ear

The right inner ear labyrinth is difficult to trace and can only be partially reconstructed (Fig. 2C). Both the right and left labyrinths (Fig. 4A–D) are missing a caudal segment of the rostral semicircular canal from after the apex of its curve to the crus commune due to damage to the caudal part of the skull. The general form of the inner ear labyrinth is typically avian with an elongate, caudally angled rostral canal, although this morphology is also common to many bird‐like theropods such as oviraptorosaurs (e.g. Balanoff et al. 2009). The cross‐sectional shape of the canals is approximately circular, unlike many avian taxa in which they are more flattened (e.g. anseriforms: Walsh & Milner, 2011b). The rostral origin of the rostral semicircular canal occurs on the rostral‐most margin of the rostral ampulla, whereas its caudal junction with the crus commune is dorsal to the caudal junction of the horizontal canal at that point. The horizontal and caudal canals are much less expanded than the rostral canal, and also have an approximately circular circumference (Table 2). The diameter of the horizontal and caudal canals is very close (Table 2). Although the caudal and rostral canals intersect at around 50°, the remaining canal intersections are almost at right angles.

Figure 4.

Left endosseous inner ear labyrinth segmented from PIN 5028/2 in (A) caudal, (B) rostral, (C) medial and (D) lateral views. ca, caudal ampulla; cc, crus commune; ccn, cochlear canal; csc, caudal semicircular canal; ha, horizontal ampulla; hsc, horizontal semicircular canal; ow, oval window; ra, rostral ampulla; rsc, rostral semicircular canal. Left labyrinth is shown because it is more complete than the right labyrinth.

Table 2.

Measurements of maximal dimensions, diameter (in mm) and semicircular canal intersection angles (in degrees) of the left and right inner ear labyrinths of Cerebavis cenomanica

| Right labyrinth | Left labyrinth | |

|---|---|---|

| Cochlear canal length | 3.14 | 2.94 |

| Cochlear canal width | 1.54 | 1.47 |

| RSC length | 4.59 | 4.35 |

| CSC diameter | 3.3 | 3.3 |

| HSC diameter | 3.2 | 3.51 |

| RSC cross‐section width | 0.37 | 0.44 |

| CSC cross‐section width | 0.57 | 0.5 |

| HSC cross‐section width | 0.48 | 0.48 |

| Angle CSC/RSC | 52.4° | 50.3° |

| Angle CSC/HSC | 90.3° | 94.6° |

| Angle RSC/HSC | 75.4° | 81.4° |

CSC, caudal semicircular canal; HSC, horizontal semicircular canal; RSC, rostral semicircular canal.

The cochlear canal is elongate and strongly directed medially and rostrally, with a slight caudally directed curvature of the distal region. The overall proportions of the canal relative to the vestibular part of the labyrinth and size of the skull and endocast appear to be well within the range of living birds (Walsh et al. 2013).

Discussion

Our reconstruction of the endocast of Cerebavis provides a clear representation of brain cavity morphology in this taxon, but a clearer understanding of the taxonomic affinities of the specimen is needed before these new data can be used to investigate trends in avian neurosensory evolution. Kurochkin et al. (2006) provided no clear synapomorphies that would nest Cerebavis within Aves, other than the avian nature of the morphology of what was believed at that time to be an endocast. Even with our new reconstruction, this morphology is not sufficient to confidently refer Cerebavis to Aves, since some non‐avian theropods and pterosaurs also had remarkably bird‐like brains. The possibility that this ‘avian’ morphology may be a plesiomorphic condition shared with some bird‐like non‐avian theropods (Balanoff et al. 2014) further weakens the use of generalized morphology as a diagnostic character at this level.

Fortunately, the skull itself, although abraded and incomplete, provides some clues. First, the walls of the skull are extremely thin, as they are in most living volant birds. The consistency of this thickness and pattern of abrasion shows that this thinness is not a taphonomic artifact. Thin bone walls are also a characteristic of pterosaur skulls, which also are well known to have an avian‐like brain form (Witmer et al. 2003), as have some bird‐like non‐avian theropods (see Balanoff et al. 2014 for discussion). However, the general cranial architecture, absence of temporal fenestrae and the degree of skull roof fusion in Cerebavis is unlike any pterosaur skull known. Although the cerebellar flocculi in the Cerebavis endocast are within the larger end of the avian flocculus size spectrum, they are far smaller than those known in pterosaurs (Witmer et al. 2003). These lines of evidence preclude referral of Cerebavis to Pterosauria or to a non‐avian bird‐like theropod.

The main line of evidence indicating an avian affinity for Cerebavis is arguably its absence of a temporal fenestrae. This implies loss of the postorbital bone, and there is certainly no evidence that a postorbital was present but not preserved. If genuinely absent, the skull of Cerebavis would differ from that of Enantiornithes, which are generally regarded to have possessed the element (O'Connor & Chiappe, 2011). Cerebavis instead appears to possess the typical ‘ornithurine’ condition (Witmer, 2002).

The degree of braincase fusion in this specimen is remarkable, and closely resembles that observed in living neognaths. This character provides further evidence that Cerebavis is not an enantiornithine, as representatives of that clade retain unfused cranial sutures (O'Connor & Chiappe, 2011). To our knowledge, no known Mesozoic avian skull, including specimens referred to Ornithurae, exhibits the same degree of fusion, and even volant palaeognathous birds (Tinamidae and Lithornithidae) and some basal neognathous birds (Pelagornithidae) retain some open sutures (Houde, 1988; Elzanowski & Galton, 1991; Milner & Walsh, 2009; Bourdon et al. 2010). This light, fusion‐strengthened construction is entirely consistent with advanced flight adaptation of a kind seen in living Neoaves, and surely more advanced than would be expected in a 95–93 Myr old bird. However, the possibility exists that the sutures are in some way obscured on the bone surface and that the resolution of the μCT dataset is insufficient to identify them internally. At this time we prefer not to overemphasize the importance of the apparent absence of sutures until the specimen can be rescanned at a higher resolution. Nonetheless, based on present evidence it seems likely that Cerebavis is an ornithurine bird rather than an enantiornithine bird.

With a brain cavity volume of 0.75 cm3, the brain of Cerebavis was almost half the volume of that of Archaeopteryx (1.4 cm3 as measured and 1.6 cm3 including volume estimated for missing portions; Domínguez Alonso et al. 2004, 1.44 cm3; Balanoff et al. 2013), despite the two skulls being similar in length. The disparity between our volume estimate and that of Kurochkin et al. (2007) for Cerebavis is obviously a result of those authors’ estimate being based on the volume of the whole skull rather than the endocast. Our measure is likely to be a very slight underestimate because a small part of the cerebellum is missing, although as discussed above this missing portion is unlikely to be significant. These estimates for Cerebavis are unfortunately of limited use in tracing the expansion of the avian brain during the Mesozoic, because without associated postcranial remains, they cannot be placed reliably into overall body size context. Consequently, discussion of trends in avian brain size evolution given by Kurochkin et al. (2006, 2007) lack foundation until more complete remains of this taxon are recovered and a reliable estimate of body mass made from them.

Although not useful for higher taxon referral, the overall gross brain morphology of Cerebavis is similar to that of most living avian taxa in its degree of lateral and dorsoventral telencephalic expansion and degree of brain axis flexure. As such, the brain of Cerebavis appears to have been more derived than the more elongate form of Archaeopteryx. However, Kawabe et al. (2013) noted a tendency for smaller taxa to have ‘rounder’, less elongate brains than larger taxa, although the reasons for this allometric trend are at present unclear. As Cerebavis appears to have been a small bird, the overall shape of the endocast may in some way relate to allometry. Skull size in Cerebavis and Archaeopteryx is similar (Kurochkin et al. 2007), so the elongate brain morphology of Archaeopteryx does not appear to fit this allometric trend. Consequently, the brain morphology of Cerebavis is consistent with morphological trends seen in living birds, and does not represent a divergent evolutionary pathway within Aves as suggested by Kurochkin et al. (2006).

The relatively large size of the optic lobes and cerebellum in Cerebavis are expected as part of the neural adaptation for flight (e.g. Domínguez Alonso et al. 2004) and merit little discussion here. Although comparatively large, the optic lobes of the mesencephalon in themselves do not show any particular visual specialization, and the suggestion of Kurochkin et al. (2007) that Cerebavis may have had optimization for nocturnal vision cannot be substantiated because the evidence for these suggestions was based on misinterpretation of the specimen as an endocast.

The relative size of the olfactory lobes was noticeably larger than that of Archaeopteryx, although, proportional to the rest of the brain, they appear to be within the range of living birds. The apparent olfactory lobe enlargement in Cerebavis some 50 Myr after Archaeopteryx is consistent with the trend toward increased reliance on olfaction noted by Zelenitsky et al. (2011) in basal birds. However, without body mass estimates for Cerebavis, this cannot be further investigated.

The absence of a wulst is intriguing. This structure is a dorsal expansion of the telencephalon that is present to a varying extent in all living birds. The wulst is largest and composed of the highest numbers of binocular cells in species that possess greater degrees of stereopsis (Iwaniuk & Wylie, 2006), but the structure is also involved in a number of other cognitive processes including navigation during migration (Mouritsen et al. 2005). We have previously suggested (Milner & Walsh, 2009) that the evolution of the wulst may have been a crucial factor in neornithine survival at the K‐Pg extinction, as it may have provided these early neornithines with enhanced visual cognition and food‐finding behavioral flexibility. Neornithine wulst development was already well within the range of living birds early in the Cenozoic, so it is likely the structure appeared at some point during the Mesozoic (Walsh & Milner, 2011b). Absence of the structure at this time in any other avian clades (i.e. Enantiornithes) that were present at the K‐Pg extinction would support the model of neornithine survival through enhanced cognition, but brain shape in Enantiornithes has not yet been described. It is entirely possible that the neural structures constituting the fully developed wulst in extant birds were already present but too poorly developed within the dorsal portion of the telencephalon of Cerebavis to leave an impression on the endocranium. Leaving such conjectures aside, if Cerebavis really is an ornithurine, the wulst had clearly either not yet evolved to a degree noticeable on an endocast by 95–93 Mya, or it appeared in another ornithurine ancestor directly on the line to Neornithes.

We are unconvinced that the faint depression on the telencephalic cast of the ‘London’ Archaeopteryx noted by Balanoff et al. (2013) actually is a rudimentary wulst. This hypothesis is unlikely as it requires the evolution of a complex and ontogenetically novel (Pearson, 1972) neural structure even before the main expansion of ontogenetically older telencephalic regions that give the modern avian brain much of its increased encephalization (Dubbeldam, 1998). To date, wulst development has only been demonstrated in Cenozoic Neornithes (Walsh & Milner, 2011a), and in all of those the wulst occupies a limited rostral position on the dorsal surface of the telencephalon. If the feature in Archaeopteryx is the impression of this structure, its coverage from the rostral‐most to almost the caudal‐most margins of the telencephalon would have been extraordinarily extensive and therefore highly advanced, even if the dorsal expression of the structure was poor. Since Archaeopteryx is not ancestral to Ornithurae (e.g. O'Connor & Zhou, 2013), the absence of a wulst in Cerebavis (a probable ornithurine) would either mean that the structure arose more than once (in the ancestor of Archaeopteryx and then in the ornithurine lineage more than 55 Myr later), or that it arose once in a common ancestor of Archaeopteryx and Ornithuromorpha and was subsequently lost and reacquired in ornithuromorph birds. Since the loss and reacquisition of such an apparently well developed complex neural structure is difficult to envisage, a multiple origin hypothesis could be more parsimonious. However, since the presence of this impression cannot be verified on the opposite telencephalic hemisphere (Domínguez Alonso et al. 2004) we suggest the presence of a wulst in Archaeopteryx should be regarded with caution unless it is found in other Archaeopteryx specimens.

The size of the cranial nerves in Cerebavis is largely as expected for a bird of this size. However, compared with many living species, the size of the trigeminal (CNV) nerve foramen in Cerebavis is relatively narrow. In living birds, endocasts of the trigeminal foramina tend to be broader in species that rely on mandibular tactile sense for tool use (e.g. corvids) or have mandibular sensory specializations (e.g. kiwi, skimmers) than in species making more use of their feet for object manipulation (e.g. psittaciforms; SA Walsh, pers. obs.), although this has not been tested empirically. The significance of this relationship for the behavior of Cerebavis is at present unclear, but it seems unlikely that the bill of this taxon possessed sensory specializations, and the small size of the nerve bundle could also be related to a relatively small terminal area of sensory innervation (i.e. the bill of Cerebavis may have been small relative to most living birds).

The overall morphology of the inner ear of Cerebavis is typically avian, but in essence not drastically different from that of many non‐avian theropods such as Incisivosaurus gauthieri (Balanoff et al. 2009). The elongate, caudally directed rostral canal in particular is a feature shared by most birds and theropods, and has been interpreted to have evolved for monitoring pitching motion of the head during bipedal locomotion (Sipla, 2007). In this respect, the relative expansion of the three canals is plesiomorphic, and although the caudal and horizontal canals have a relatively small diameter, they are still within the range of living avian species (SA Walsh, pers. obs.). The cochlear canal is elongate and looks proportionately as long relative to the vestibular region of the labyrinth as that of most birds, except palaeognaths, in which the cochlear canal tends to be relatively shorter (Walsh et al. 2009). It is not possible to provide an estimate of hearing sensitivity using the methods of Walsh et al. (2009), since the missing occipital condyle in this specimen makes measurement of basicranial length (required for scaling) uncertain.

Lastly, the preservation of both pterygoids may prove useful for determining the morphology of the palate and presence of cranial kinesis in Cerebavis, but the difficulty in tracing their shape in the scan data used here means that the elements cannot be fully reconstructed. It is likely that a new X‐ray μCT scan of the specimen will be able to resolve ambiguities in our analysis, particularly those relating to the path of the cranial nerves.

Conclusions

Our μCT‐based reconstruction of the skull and endocranial space of Cerebavis cenomanica has provided new and robust information with which to rediagnose the taxon, as well as demonstrating the morphology of the brain cavity endocast, internal cavities and inner ear labyrinth. These data suggest Cerebavis was an ornithurine rather than an enantiornithine, and although no wulst development is apparent, its brain was remarkably modern in external morphology. Due to its initial misinterpretation as an endocast, the inferences about the neurosensory development of this taxon provided by Kurochkin et al. (2006, 2007) are mostly invalid. However, our analysis does not reveal that Cerebavis possessed any major specializations beyond those expected for the brain of a bird. The overall significance of the specimen for answering important questions about avian encephalization in the clade that includes modern birds is unfortunately diminished without body mass estimates. However, apart from a tiny missing portion of cerebellum, Cerebavis has the most completely known brain morphology of any Mesozoic bird; that of Archaeopteryx is known only for one side. Furthermore, as one of only four Mesozoic ornithurines for which brain morphology has been described in any degree of completeness, this specimen will be important for any future investigation of pre‐Cenozoic avian brain evolution.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the late Evgeny Kurochkin for providing a copy of the original CT slice data to EB. We thank Dave Martill, Darren Naish (University of Portsmouth) and Monja Knoll (University of the West of Scotland) for useful discussion, and particularly Dave Martill (University of Portsmouth) for his help with pterosaur skull comparisons. This work was supported by Marie Curie Intra European Fellowship number 255039 and Carlsberg grant number 2013_01_0480 (Carlsbergfondet) to EB and NERC grant number NE/H012176/1 to SAW. The authors declare no conflicting interests.

References

- Balanoff AM, Xu X, Kobayashi Y, et al. (2009) Cranial osteology of the theropod dinosaur Incisivosaurus gauthieri (Theropoda: Oviraptorosauria). Am Mus Novit 3651, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Balanoff AM, Bever GS, Rowe TB, et al. (2013) Evolutionary origins of the avian brain. Nature 7465, 93–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balanoff AM, Bever GS, Norell MA (2014) Reconsidering the avian nature of the oviraptorosaur brain (Dinosauria: Theropoda). PLoS ONE 9, e113559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett PM, Milner AC (2007) Comment on the proposed conservation of usage of Archaeopteryx lithographica von Meyer, 1861 (Aves) by designation of a neotype. Bull Zool Nomen 64, 261–262. [Google Scholar]

- Baumel JJ, Witmer LM (1993) Osteologia In: Handbook of Avian Anatomy: Nomina Anatomica Avium. (eds Baumel JJ, King AS, Breazile JE, Evans HE, Vanden Berge JC.), pp. 45–132. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club. [Google Scholar]

- de Beer G (1954) Archaeopteryx Lithographica. London: British Museum. [Google Scholar]

- Bertelli S, Chiappe LM, Mayr G (2014) Phylogenetic interrelationships of living and extinct Tinamidae, volant palaeognathous birds from the New World. Zool J Linn Soc 172, 145–184. [Google Scholar]

- Bock WJ (1963) The cranial evidence for ratite affinities. Proc Int Ornith Cong 13, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boessenecker RW, Perry FA, Schmitt JG (2014) Comparative taphonomy, taphofacies, and bonebeds of the Mio‐Pliocene Purisima Formation, Central California: strong physical control on marine vertebrate preservation in shallow marine settings. PLoS ONE 9, e91419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon E, Bouya B, Iarochène M (2005) Earliest African Neornithine bird: a new species of Prophaethontidae (Aves) from the Paleocene of Morocco. J Vertebr Paleontol 25, 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdon E, Amaghzaz M, Bouya B (2010) Pseudo‐toothed birds (Aves, Odontopterygiformes) from the Early Tertiary of Morocco. Am Mus Novit 3704, 1–71. [Google Scholar]

- Burnham DA (2004) New information of Bambiraptor feinbergi (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Montana In: Feathered Dragons: Studies on the Transition from Dinosaurs to Birds. (eds Currie P, Koppelhaus EB, Shugar MA, Wright JL.), pp. 67–111. Bloomington: Indiana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee S (1991) Cranial anatomy and relationships of a new Triassic bird from Texas. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B 332, 277–342. [Google Scholar]

- Cracraft J (1988) The major clades of birds In: The Phylogeny and Classification of the Tetrapods, Vol. 1: Amphibians, Reptiles, Birds. (ed. Benton MJ.), pp. 339–361. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez Alonso P, Milner AC, Ketcham RA, et al. (2004) The avian nature of the brain and inner ear of Archaeopteryx . Nature 430, 666–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubbeldam JL (1998) Birds In: The Central Nervous System of Vertebrates, vol. 3 (eds Nieuwenhuys R, Ten Donkelaar HJ, Nicholson C.), pp. 1525–1636. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger T (1926) The brain of Archaeopteryx . Ann Mag Nat Hist 18, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Edinger T (1951) The brains of the Odontognathae. Evolution 5, 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Elzanowski A (1991) New observations on the skull of Hesperornis, with reconstructions of the bony palate and otic region. Postilla 207, 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Elzanowski A, Galton PM (1991) Braincase of Enaliornis, an Early Cretaceous bird from England. J Vertebr Paleontol 11, 90–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hall MI, Iwaniuk AN, Gutíerrez‐Ibáñez C (2009) Optic foramen morphology and activity pattern in birds. Anat Rec 292, 1827–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houde P (1988) Paleognathous Birds from the Early Tertiary of the Northern Hemisphere. Cambridge: Nuttall Ornithological Club; 22, pp. 148. [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniuk AN, Nelson J (2002) Can endocranial volume be used as an estimate of brain size in birds? Can J Zool 80, 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Iwaniuk AN, Wylie DRW (2006) The evolution of stereopsis and the Wulst in caprimulgiform birds: a comparative analysis. J Comp Physiol A 192, 1313–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerison HJ (1968) Brain evolution and Archaeopteryx . Nature 219, 1381–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerison HJ (1973) Evolution of the Brain and Intelligence. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kawabe S, Shimokawa T, Miki H, et al. (2013) Variation in avian brain shape: relationship with size and orbital shape. J Anat 223, 495–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundrát M (2007) Avian‐like attributes of a virtual brain model of the oviraptorid theropod Conchoraptor gracilis . Naturwissenschaften 94, 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurochkin EN, Saveliev SV, Postnov AA, et al. (2006) On the brain of a primitive bird from the Upper Cretaceous of European Russia. Paleontol J 40, 655–667. [Google Scholar]

- Kurochkin EN, Saveliev SV, Dyke GJ, et al. (2007) A fossil brain from the Cretaceous of European Russia and avian sensory evolution. Biol Lett 3, 309–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh OC (1880) Odontornithes: A Monograph on the Extinct Toothed Birds of North America. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell S (1948) The bony palate of birds. Part I: the Palaeognathae. Auk 65, 520–549. [Google Scholar]

- Milner AC, Walsh SA (2009) Avian brain evolution: new data from Palaeogene birds (Lower Eocene) from England. Zool J Linn Soc 155, 198–219. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen H, Feenders G, Liedvogel M, et al. (2005) Night‐vision brain area in migratory songbirds. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 102, 8339–8344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norell MA, Makovicky PJ, Bever GS, et al. (2009) A review of the Mongolian Cretaceous dinosaur Saurornithoides (Troodontidae: Theropoda). Am Mus Novit 3654, 1–63. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor JK, Chiappe LM (2011) A revision of enantiornithine (Aves: Ornithothoraces) skull morphology. J Syst Palaeontol 9, 135–157. [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor JK, Zhou Z (2013) A redescription of Chaoyangia beishanensis (Aves) and a comprehensive phylogeny of Mesozoic birds. J Syst Palaeontol, 11, 889–906. [Google Scholar]

- Osmólska H (2004) Evidence on relation of brain to endocranial cavity in oviraptorid dinosaurs. Acta Pal Pol 49, 321–324. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson R (1972) The Avian Brain. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Portmann A, Stingelin W (1961) The central nervous system In: The Biology and Comparative Physiology of Birds, vol. 2 (ed. Marshall AJ.), pp. 1–36. New York: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pycraft WP (1900) On the morphology and phylogeny of the Palaeognathae (Ratitae and Crypturi) and Neognathae (Carinatae). Trans Zool Soc Lond 15, 149–290. [Google Scholar]

- Salzen EA, Parker DM (1975) Arousal and orientation functions of the avian telencephalon In: Neural and Endocrine Aspects of Behavior in Birds. (eds Wright P, Caryl PG, Vowles DM.), pp. 205–242. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Sipla JS (2007) The semicircular canals of birds and nonavian dinosaurs. Unpublished PhD Thesis. New York: Stony Brook University. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SA, Knoll MA (2011) Directions in palaeoneurology. Spec Pap Pal 86, 263–279. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SA, Martill DM (2006) A possible earthquake‐triggered mega‐boulder slide in a Chilean Mio‐Pliocene marine sequence: evidence for rapid uplift and bonebed genesis. J Geol Soc Lond 163, 697–705. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SA, Milner AC (2011a) Evolution of the avian brain and senses In: Living Dinosaurs: The Evolutionary History of Modern Birds. (eds Dyke G, Kaiser G.), pp. 282–305. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SA, Milner AC (2011b) Halcyornis toliapicus (Aves: Lower Eocene, England) indicates advanced neuromorphology in Mesozoic Neornithes. J Syst Paleontol 9, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SA, Barrett PM, Milner AC, et al. (2009) Inner ear anatomy is a proxy for deducing auditory capability and behaviour in reptiles and birds. Proc R Soc Lond B 276, 1355–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SA, Iwaniuk AN, Knoll MA, et al. (2013) Avian cerebellar floccular fossa size is not a proxy for flying ability in birds. PLoS ONE 8, e67176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witmer LM (2002) The debate on avian ancestry: phylogeny, function and fossils In: Mesozoic Birds: Above the Heads of Dinosaurs. (eds Chiappe LM, Witmer LM.), pp. 3–30. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Witmer LM, Chatterjee S, Franzosa J, et al. (2003) Neuroanatomy of flying reptiles and implications for flight, posture and behaviour. Nature 425, 950–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelenitsky DK, Therrien F, Ridgely RC, et al. (2011) Evolution of olfaction in non‐avian theropod dinosaurs and birds. Proc R Soc B 278, 3625–3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z, Zhang A (2007) Mesozoic birds of China – a synoptic review. Front Biol China 2, 1673–3509. [Google Scholar]