Abstract

Background:

BRAFV600E-mediated MAPK pathway activation is associated in melanoma cells with IFNAR1 downregulation. IFNAR1 regulates melanoma cell sensitivity to IFNα, a cytokine used for the adjuvant treatment of melanoma. These findings and the limited therapeutic efficacy of BRAF-I prompted us to examine whether the efficacy of IFNα therapy of BRAFV600E melanoma can be increased by its combination with BRAF-I.

Methods:

BRAF/NRAS genotype, ERK activation, IFNAR1, and HLA class I expression were tested in 60 primary melanoma tumors from treatment-naive patients. The effect of BRAF-I on IFNAR1 expression was assessed in three melanoma cell lines and in four biopsies of BRAFV600E metastases. The antiproliferative, pro-apoptotic and immunomodulatory activity of BRAF-I and IFNα combination was tested in vitro and in vivo utilizing three melanoma cell lines, HLA class I-MA peptide complex-specific T-cells and immunodeficient mice (5 per group for survival and 10 per group for tumor growth inhibition). All statistical tests were two-sided. Differences were considered statistically significant when the P value was less than .05.

Results:

The IFNAR1 level was statistically significantly (P < .001) lower in BRAFV600E primary melanoma tumors than in BRAF wild-type tumors. IFNAR1 downregulation was reversed by BRAF-I treatment in the three melanoma cell lines (P ≤ .02) and in three out of four metastases. The IFNAR1 level in the melanoma tumors analyzed was increased as early as 10 to 14 days following the beginning of the treatment. These changes were associated with: 1) an increased susceptibility in vitro of melanoma cells to the antiproliferative (P ≤ .04), pro-apoptotic (P ≤ .009) and immunomodulatory activity, including upregulation of HLA class I antigen APM component (P ≤ .04) and MA expression as well as recognition by cognate T-cells (P < .001), of BRAF-I and IFNα combination and 2) an increased survival (P < .001) and inhibition of tumor growth of melanoma cells (P < .001) in vivo by BRAF-I and IFNα combination.

Conclusions:

The described results provide a strong rationale for the clinical trials implemented in BRAFV600E melanoma patients with BRAF-I and IFNα combination.

BRAF inhibitors (BRAF-I) represent a major breakthrough in the treatment of metastatic melanoma harboring the BRAFV600 mutations (1–3). However, the limited efficacy of BRAF-I therapy emphasizes the need to design novel combinatorial therapies for the treatment of metastatic melanoma.

Mutant BRAFV600, a constitutively active protein serine kinase, leads to the sustained activation of MAP kinase (MAPK) pathway (4). This pathway plays a critical role in the proliferation and survival of melanoma cells (5) and in the modulation of molecules that mediate interactions of melanoma cells with immune cells (6–9). MAPK pathway activation is also known to downregulate type I IFNα receptor-1 (IFNAR1) (10), which mediates the effects of IFNα (11,12), a cytokine used for the adjuvant treatment of high-risk melanoma (13). Specifically, ERK activation (14) upregulates βTrcp2/HOS protein, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that increases the ubiquitination and degradation of IFNAR1 (15). As a result, IFNAR1 level and signaling are downregulated. These findings have provided the rationale for this study, which shows that BRAF-I enhances the antiproliferative and immunomodulatory effects of IFNα on BRAFV600E melanoma cells because inhibition of ERK activation by BRAF-I upregulates IFNAR1 expression.

Methods

Cell Cultures

The human melanoma cell lines Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 harboring the BRAFV600E mutation were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Mediatech, Inc., Manassas, VA) supplemented with 2 mmol/L L-glutamine (Mediatech, Inc.) and 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Atlanta Biologicals Flowery Branch, GA). Cells were cultured at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Characterization of melanoma cell lines is detailed in the Supplementary Materials (available online).

Chemical Reagents and Antibodies

Chemical reagents and antibodies are detailed in the Supplementary Materials (available online).

Tumor Samples

Primary melanoma tumor biopsies from treatment-naive patients were obtained from the tissue bank at Istituto Nazionale Tumori Fondazione “G. Pascale” (Naples, Italy). Biopsies of BRAFV600E metastases were obtained from patients enrolled in clinical trials with the BRAF-I (vemurafenib) at Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA). Patients gave written informed consent for tissue acquisition per institutional review board (IRB)–approved protocol. Melanoma metastases were biopsied pretreatment (day 0), at 10 to 14 days on treatment, and/or at the time of disease progression as defined by Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST). Presence of tumor cells in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues was monitored by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

Genotyping of Primary Melanoma Tumors

Genomic DNA was isolated from FFPE tumor tissues using the QIAamp DNA FFPE tissue kit (QIAGEN, Inc., Milan, Italy). The full coding sequences and splice junctions of NRAS (exons 2 and 3) and the entire sequence of the BRAF exons 11 and 15 (16,17) were screened for mutations. Quality of purified DNA was assessed in every sample to avoid discrepancies caused by poor sample quality. Primer sets were designed as described (18). Sequencing and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were performed as described (18).

Mice

C.B-17 severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) female mice (9 weeks old) and NOD.Cg-Prkdc scid Il2rg tm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG) female mice (9 weeks old) were purchased from Taconic Biosciences, Inc (Albany, NY) and from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), respectively.

Immunohistochemistry

FFPE melanoma tumor biopsies were used as substrates in immunohistochemical (IHC) assays. IHC staining is detailed in the Supplementary Materials (available online).

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot assay was performed as described (19).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cells were cell surface and intracellularly stained as described (20). Stained cells were analyzed with a flow cytometer (Cyan ADP, Beckam Coulter, Indianapolis, IN). Apoptosis induction was detected by annexin V and propidium iodide (PI; BD Bioscience) cytometric staining as described (21). Data were analyzed using Summit v4.3 software (DAKO) or BD Accuri C6 software (BD Bioscience).

Cell Proliferation

Cell proliferation was evaluated utilizing the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay (22).

Melanoma Cell Recognition by HLA-A2-MA Peptide Complex–Specific TCR-Transduced T-Cells

T-cells were transduced with a retroviral vector encoding a TCR that recognizes NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165 (SLLMWITQC) or MART-1 peptide27-35 (AAGIGILTV) in the context of HLA-A*0201 (23). Recognition of melanoma cells by transduced T-cells was tested by incubating T-cells with melanoma cells at a 1:1 ratio. Following an 18-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, the medium was harvested from the cultures and IFNγ level was measured as described (24).

In Vivo Studies

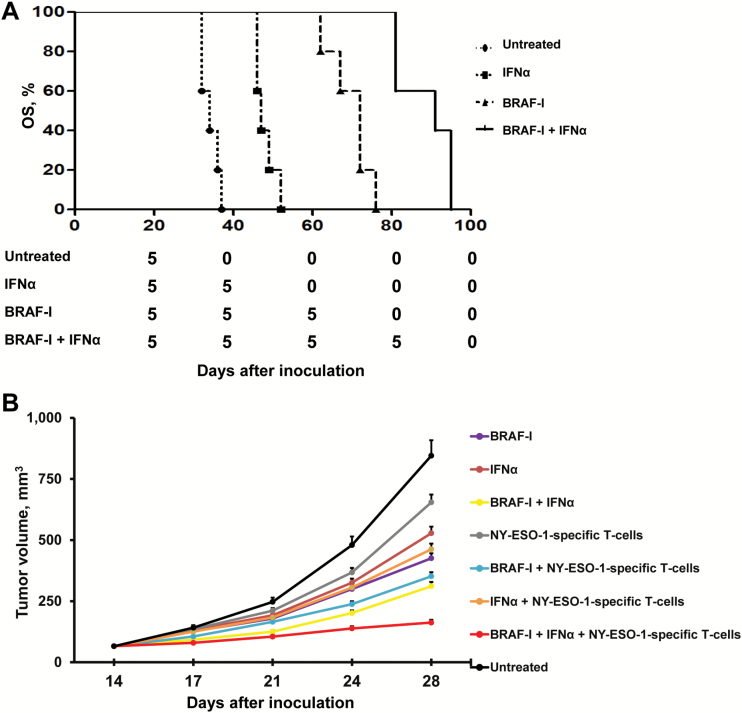

Twenty SCID mice were grafted subcutaneously in the right lateral flank with BRAFV600E M21 melanoma cells (1x106 cells/mouse). Tumor volume was measured once per week by vernier caliper. Ten days after cell inoculation, when the tumor reached a diameter of around 0.4cm, mice were randomly divided into four groups of five mice each, and treatment was started. A mouse was killed when its tumor reached the maximum diameter (1cm3) as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Overall survival (OS) of mice was monitored and recorded.

Eighty NSG mice were grafted subcutaneously in the right lateral flank with BRAFV600E SK-MEL-37 melanoma cells (1x106 cells/mouse). Tumor volume was measured twice per week by vernier caliper. Fourteen days after cell inoculation, when the tumor reached a diameter of around 0.4cm., mice were randomly divided into eight groups of 10 mice each, and treatment was started. All mice were killed when a tumor in a mouse reached the maximum diameter (1cm3) as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Tumor volume in mice was monitored and recorded.

Mouse studies were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital IACUC. The investigator who monitored and recorded tumor volume and OS of mice was blinded to the type of treatment received by the mice.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software (StataCorp LP; College Station, TX). Averages and standard deviations were calculated using Microsoft Excel. The difference between groups was calculated using the two-sided, unpaired t test. Correlation between tumor genotype and protein expression in tumor biopsies was calculated using Fisher’s exact test. Correlation between proteins expressed in tumor biopsies was calculated using the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Treated mice’s OS was analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method; difference among groups was calculated using the log-rank test. Differences were considered statistically significant when the P value was less than .05. All statistical tests were two-sided.

Results

IFNAR1 Expression in BRAFmutant Primary Melanoma Cells

Sixty tumor biopsies were genotyped for BRAF/NRAS and analyzed for pERK, IFNAR1, and HLA class I expression (Figure 1A). HLA class I expression was used to monitor IFNAR1 activity (11,25). BRAF (V600E, V600K, and V600D) and NRAS (Q61R) mutations were detected in 38 (63.3%) and three (5.0%), respectively, of the 60 tumors biopsies. Both BRAFV600D and NRASQ61L mutations were present in one (1.7%) of the 60 tumors. No mutations in BRAF and NRAS were detected in the remaining 18 (30.0%) of the 60 tumors (Supplementary Table 1, available online). Because of the low number, tumors carrying NRAS mutation were excluded from subsequent analyses. pERK expression was high and low in 36 (64.3%) and 20 (35.7%), respectively, of the 56 tumors analyzed. Additionally, IFNAR1 expression was low and high in 34 (60.7%) and 22 (39.3%), respectively, of the 56 tumors. Lastly, HLA class I antigen expression was in the normal range and downregulated in 22 (39.3%) and 34, respectively, of the 56 tumors (60.7%).

Figure 1.

Association of IFNAR1 downregulation with ERK activation in BRAF-mutant primary melanoma tumor biopsies from treatment-naive patients. Sixty primary melanoma tumors were genotyped for BRAF/NRAS and immunohistochemistry (IHC)-stained with pERK (D11A8)-, IFNAR1/IFNAR (C-Terminus)-specific antibodies, and a pool of mouse HLA-A-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) HCA2 and HLA-B/C-specific mAb HC10 (1:1). Rabbit IgG was used as a specificity control for rabbit antibodies. mAb MK2-23, an IgG1, and mAb F3-C25, an IgG2a, were used as specificity controls for mAb HCA2 and mAb HC10, respectively. A) Representative IHC staining of pERK, IFNAR1, and HLA class I antigens in primary melanoma tumors are shown. The magnification and scale bar used are indicated in the panels of the figures. B) Two groups of tumor genotypes (BRAFmutant vs BRAF/NRASwild-type) were associated with pERK score groups by Fisher’s exact test. C) Two groups of tumor genotypes (BRAFmutant vs BRAF/NRASwild-type) were associated with IFNAR1 score groups by Fisher’s exact test. D) IFNAR1 score groups were associated and correlated with pERK score groups by Fisher’s exact test and Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, respectively. All statistical tests were two-sided.

pERK expression was statistically significantly (Fisher’s exact P < .001) increased in BRAF mutant melanomas as compared with wild-type BRAF/NRAS tumors (Figure 1B; Supplementary Table 2, available online). Furthermore, BRAF mutations were statistically (Fisher’s exact P < .001) associated with a lower IFNAR1 expression (Figure 1C; Supplementary Table 3, available online). Lastly, pERK expression was negatively (Fisher’s exact P = .001; Spearman’s rho= - 0.4688, P < .001) associated with IFNAR1 expression (Figure 1D; Supplementary Table 4, available online). No association was found between BRAF mutation, pERK, IFNAR1, and HLA class I expression.

Effect of BRAF-I on IFNAR1 Expression in BRAFV600E Melanoma Cell Lines and Melanoma Tumors

Colo38, M21, and SK-Mel-37 cells were highly sensitive to the antiproliferative activity of BRAF-I vemurafenib (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Treatment with BRAF-I statistically significantly (P ≤ .02) increased IFNAR1 expression as compared with untreated cells in the three cell lines (Figure 2A; Supplementary Figure 2A, available online). Similar results were obtained in biopsies of metastases from patients treated with BRAF-I. IFNAR1 was upregulated in three out of four patients treated with BRAF-I. IFNAR1 upregulation in melanoma tumors was detected as early as 10 to 14 days following the beginning of the treatment (Figure 2B; Supplementary Table 5, available online). Treatment with BRAF-I statistically significantly (P < .001) increased also IFNAR2 expression as compared with untreated cells in M21 and SK-MEL-37 cell lines but had no detectable effect on Colo38 cells (Supplementary Figure 2B, available online).

Figure 2.

IFNAR1 upregulation in BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines and metastases from patients treated with BRAF-I. A) BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 were seeded at the density of 1x105 per well in a six-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM). Untreated cells were used as a control. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle of vemurafenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. Following an up to six-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and lysed. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blot with IFNAR1/IFNAR (C-Terminus, clone EP899Y)-specific antibody. β-actin was used as a loading control. Representative results are shown (left panel). The levels of IFNAR1 normalized to β-actin are plotted and expressed as means ± SD of the results obtained in three independent experiments (right panel). All P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test. B) Four BRAFV600E metastases were biopsied before treatment (day 0), at 10 to 14 days on treatment, and/or at the time of disease progression following treatment with BRAF-I. Tumor sections were stained with hematoxylin and IFNAR1/IFNAR (C-Terminus)-specific antibody. Rabbit IgG was used as a specificity control. Representative immunohistochemistry staining of IFNAR1 expression in a melanoma patient before treatment, at 10 to 14 days on treatment, and at the time of disease progression is shown. The magnification and scale bar used are indicated in the panels of the figure. Score value of IFNAR1 expression is indicated.

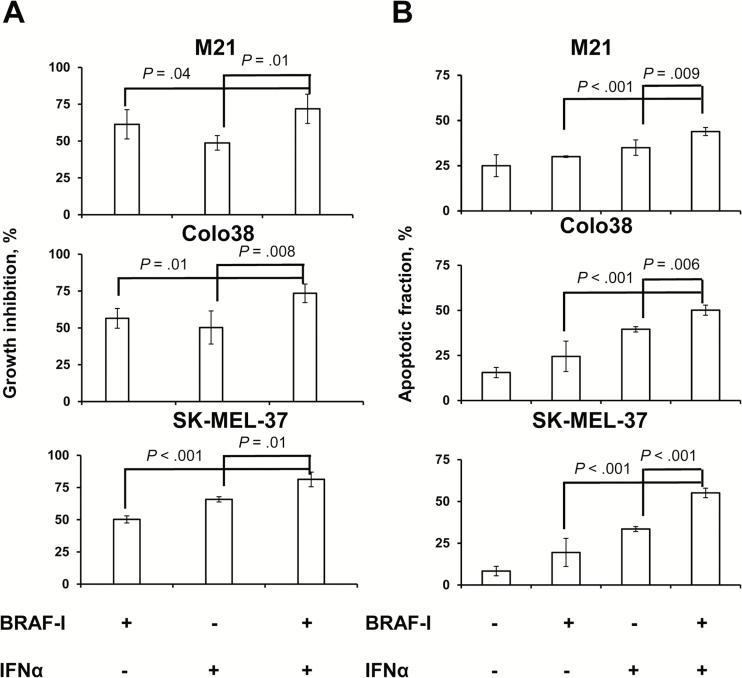

Antitumor Activity of BRAF-I and IFNα-2b Combination in BRAFV600E Melanoma Cell Lines

Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 cells were treated with BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination. The IC50 dose of IFNα-2b was 10 000 IU/mL (Supplementary Figure 1, available online). Vemurafenib and IFNα-2b combination inhibited the proliferation (Figure 3A; Supplementary Figure 3A, available online) and induced apoptosis (Figure 3B; Supplementary Figure 3B, available online) of Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 cells to a statistically significantly (P ≤ .04 and P ≤ .009, respectively) greater extent than each individual agent. Furthermore, BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination markedly increased cleaved PARP as compared with each individual agent (Figure 4A). It is noteworthy that IFNα-2b induced apoptosis while vemurafenib did not.

Figure 3.

Enhancement by BRAF-I of the in vitro antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity of IFNα in BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines. A) BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 were seeded at the density of 2.5x103 per well in a 96-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM) and/or IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/mL). Untreated cells were used as a control. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle of vemurafenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. Following a three-day incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, growth inhibition was determined by 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay. Data are expressed as percentages of growth inhibition ± SD of treated cells as compared with untreated cells. Percent of growth inhibition and SD were calculated from three independent experiments; each of them was performed in triplicate. B) BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 were seeded at the density of 1x105 per well in a six-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM) and/or IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/mL). Untreated cells were used as a control. DMSO (vehicle of vemurafenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. Following a 24-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, apoptosis induction was determined by flow cytometry analysis of annexin V and PI staining. The levels of apoptosis are plotted and expressed as mean fraction of annexin V + cells ± SD of the results obtained in three independent experiments. All P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test.

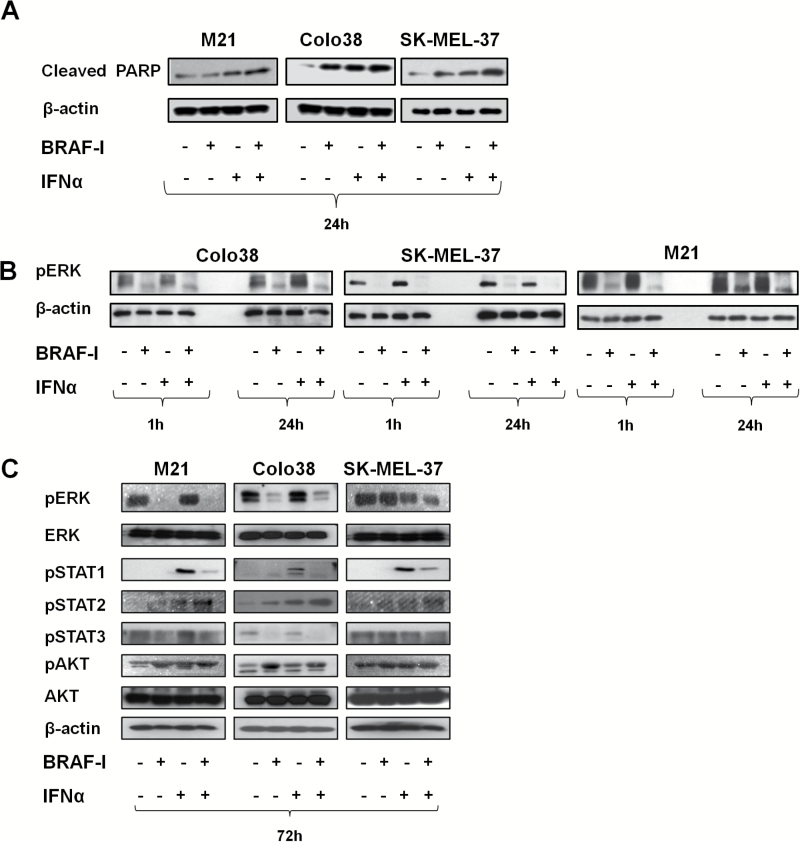

Figure 4.

Mechanisms underlying the enhancement by BRAF-I of the antiproliferative and pro-apoptotic activity of IFNα in BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines. BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 were seeded at the density of 1x105 per well in a six-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM) and/or IFNα (10 000 UI/mL). Untreated cells were used as a control. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle of vemurafenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. A) Following a 24-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and lysed. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blot with Cleaved PARP-specific antibody. β-actin was used as a loading control. Representative results are shown. B) Following an up to 24-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and lysed. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blot with pERK-specific antibody. β-actin was used as a loading control. Representative results are shown. C) Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and lysed. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blot with the indicated mAbs. β-actin was used as a loading control. Representative results are shown.

Modulation of Signaling Pathways by BRAF-I and IFNα-2b Combination in BRAFV600E Melanoma Cell Lines

pERK expression was markedly decreased in Colo38 and M21 cells following an up to 72-hour incubation with vemurafenib. In contrast, it was decreased in SK-MEL-37 cells incubated for up to 24 hours with vemurafenib but was not changed in the cells incubated for up to 72 hours. pERK expression was not changed in Colo38 and M21 cells treated with IFNα-2b for up to 72 hours but was decreased in SK-MEL-37 cells. Nevertheless, vemurafenib and IFNα-2b combination decreased pERK expression more markedly than each individual agent in the three cell lines (Figure 4B).

pSTAT1 and pSTAT2 were upregulated after treatment with IFNα-2b in the three cell lines, while only pSTAT2 was upregulated after treatment with BRAF-I. Furthermore, pSTAT3 was decreased in Colo38 and M21 cells after treatment with BRAF-I but was increased in SK-MEL-37 cells. Vemurafenib and IFNα-2b combination increased pSTAT2 expression more markedly than each individual agent in the three cell lines. In contrast, the combination displayed an effect similar to that of vemurafenib alone on pSTAT1 and pSTAT3 (Figure 4C). Lastly, pAKT was increased in the three cell lines treated with BRAF-I and only slightly downregulated in Colo38 and SK-MEL-37 cells incubated with BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination (Figure 4C).

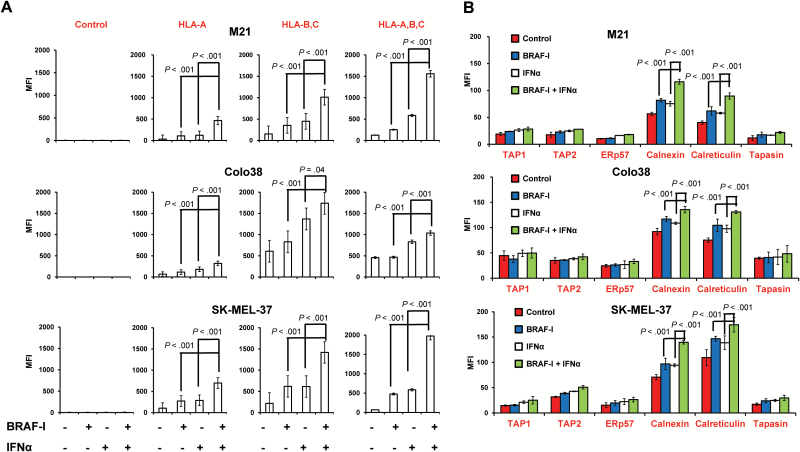

Immunomodulatory Activity of BRAF-I and IFNα-2b Combination in BRAFV600E Melanoma Cell Lines

BRAF-I and IFNα-2b displayed differential effects on HLA class I antigen processing machinery (APM) component expression in Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 cells. BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination increased HLA-A, B, and C antigen, calnexin, and calreticulin expression to a statistically significantly (P ≤ .04) greater extent than each individual agent in the three cell lines (Figure 5, A and B). It is noteworthy that not only the intracellular level but also the membrane-bound expression of calnexin and calreticulin by melanoma cells was increased by BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination to a statistically significantly (P < .001) greater extent than by each individual agent (Supplementary Figure 4, available online).

Figure 5.

Enhancement by BRAF-I of HLA class I APM component upregulation by IFNα in BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines. BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 were seeded at the density of 1x105 per well in a six-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM) and/or IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/mL). Untreated cells were used as a control. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle of vemurafenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. A) Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and cell surface stained with the indicated HLA class I antigen-specific mAbs. mAb MK2-23 was used as a specificity control. Cell staining was detected by R-phycoerythrin(PE)-conjugated F(ab’)2 fragment goat antimouse IgG. Data are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ± SD of the results obtained in three independent experiments. B) Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and intracellularly stained with the indicated APM component–specific mAbs. mAb MK2-23 was used as a specificity control (data not shown). Cell staining was detected by R-phycoerythrin(PE)-conjugated F(ab’)2 fragment goat antimouse IgG. Data are expressed as MFI ± SD of the results obtained in three independent experiments. All P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test.

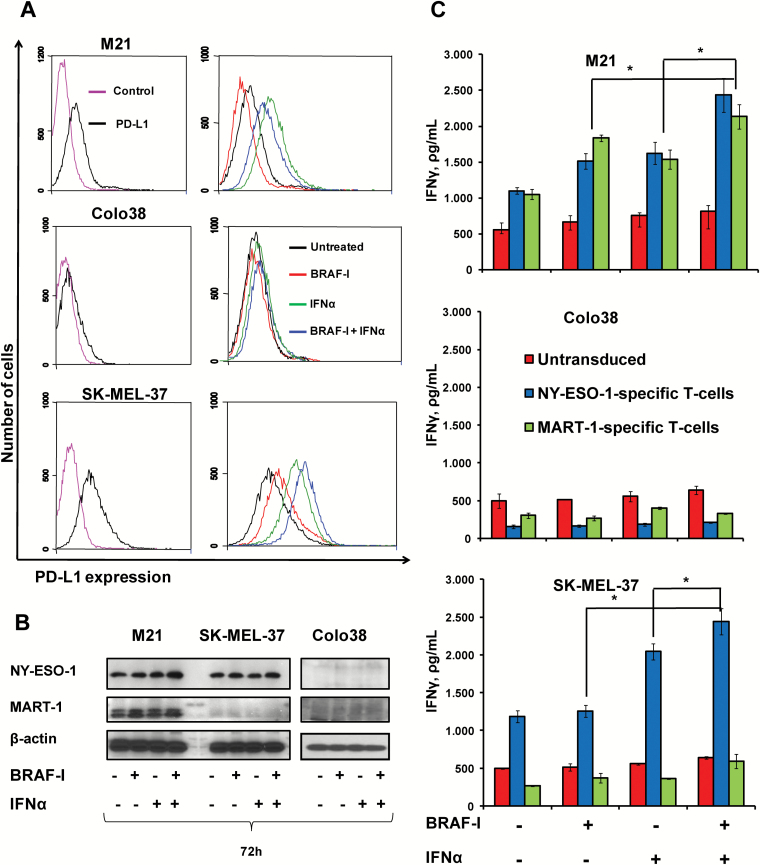

Among the other immunologically relevant molecules HLA-DR, DQ and DP antigens were statistically (P < .05) upregulated by IFNα-2b in the three cell lines to an extent similar to that induced by the BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination (Supplementary Figure 5, available online). Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) was not detected on Colo38 cells even when they were treated with BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination (Figure 6A; Supplementary Figure 6, available online). PD-L1 was differentially modulated on the other two cell lines by BRAF-I and/or IFNα-2b. BRAF-I statistically significantly (P = .009) decreased the PD-L1 upregulation induced by IFNα-2b on M21 cells but statistically significantly (P = .008) increased it on SK-MEL-37 cells (Figure 6A; Supplementary Figure 6, available online).

Figure 6.

Enhancement by BRAF-I of the immunomodulatory activity of IFNα in BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines. BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38, M21, and SK-MEL-37 were seeded at the density of 1x105 per well in a six-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM) and/or IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/mL). Untreated cells were used as a control. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle of vemurafenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. A) Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and cell surface stained with PE-conjugated PD-L1-specific mAb. PE-conjugated IgG1 was used as a specificity control. Representative results are shown. B) Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and lysed. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blot with the indicated mAbs. β-actin was used as a loading control. C) Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were cocultured with HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165- or HLA-A2-MART-1 peptide27-35-complex-specific T-cells in a 1:1 ratio. Untransduced T-cells were used as a control. Following an 18-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, IFNγ levels in the medium harvested from cultures of T-cells with target cells were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. Data are expressed as IFNγ levels ± SD of the results obtained in three independent experiments; each of them was performed in triplicate. *Indicates P < .001. All P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test.

Melanoma antigens (MAs) NY-ESO-1 and MART-1 were not detected in Colo38 cells even following treatment with both agents. Similarly, MART-1 was not detected in SK-MEL-37 cells even following treatment with the two agents. In contrast, NY-ESO-1 expression in M21 and SK-MEL-37 cells and MART-1 expression in M21 cells were upregulated by BRAF-I. IFNα-2b upregulated NY-ESO-1 and MART-1 in M21 cells but had no detectable effect on NY-ESO-1 in SK-MEL-37 cells. However, BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination increased NY-ESO-1 and MART-1 more markedly than each individual agent in both cell lines (Figure 6B; Supplementary Figure 7, available online). Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 4 (CSPG4), B7-H3, and ICAM-1 were decreased after BRAF-I treatment; the effect of BRAF-I was not changed by its combination with IFNα-2b. In contrast, CD44 expression on the three cell lines was upregulated by both BRAF-I and IFNα-2b; the effect became statistically significantly (P ≤ .04) greater following treatment with BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination (Supplementary Figure 5, available online).

To assess the functional significance of the changes induced by BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination in the biomarkers tested, we investigated the effect on the recognition of melanoma cells by cognate T-cells following treatment with vemurafenib and/or IFNα-2b. In SK-MEL-37 cells, which express NY-ESO-1 but do not express MART-1, treatment with IFNα-2b statistically significantly (P < .001) increased IFNγ release by HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells as compared with untreated cells or cells treated with vemurafenib. Furthermore, vemurafenib and IFNα-2b combination increased T-cell recognition of melanoma cells to a statistically significantly (P < .001) greater extent than each individual agent (Figure 6C). As expected, no statistically significant changes in IFNγ release were found when SK-MEL-37 cells were incubated with HLA-A2-MART-1 peptide27-35-complex-specific T-cells or untrasduced T-cells. In addition, treatment with BRAF-I or IFNα-2b of M21 cells, which express both MART-1 and NY-ESO-1, statistically significantly (P < .001) increased IFNγ release by HLA-A2-MART-1 peptide27-35-complex-specific T-cells and HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells as compared with untreated cells. However, vemurafenib and IFNα-2b combination increased T-cell recognition of melanoma cells to a statistically significantly (P < .001) greater extent than each individual agent (Figure 6C). No statistically significant changes were found, even after treatment with vemurafenib and IFNα-2b, in Colo38 cells that express neither MART-1 nor NY-ESO-1 (Figure 6C).

In Vivo Antitumor Activity of BRAF-I and IFNα-2b Combination in BRAFV600E Melanoma Cell Lines

The in vivo relevance of the described in vitro results is indicated by the following lines of evidence. First, vemurafenib prolonged the OS of SCID mice grafted with M21 cells statistically significantly more (P < .001) than IFNα-2b as compared with untreated mice. However, vemurafenib and IFNα-2b combination prolonged the OS of mice statistically significantly (P < .001) more than each individual agent (Figure 7A). In addition, the combination of BRAF-I, IFNα-2b, and HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells inhibited the growth of SK-MEL-37 cells grafted in NSG mice statistically significantly (P < .001) more than HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex- specific T-cells in combination with IFNα-2b or with BRAF-I (Figure 7B). Furthermore, vemurafenib inhibited the growth of SK-MEL-37 cells in NSG mice to a statistically significantly (P < .001) greater extent than IFNα-2b or HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells as compared with untreated mice. Lastly, all the agents used in double combinations inhibited the in vivo growth of SK-MEL-37 cells statistically significantly (P < .001) more than each individual agent. It is noteworthy that administration of the drugs or T-cells, either in combination or as individual agents, caused no overt side effects (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Enhancement by BRAF-I of the antitumor activity of IFNα in BRAFV600E melanoma cells grafted in immunodeficient mice treated with adoptive T-cell therapy. A) M21 cells were implanted subcutaneously in 20 SCID mice. When tumors became palpable, mice were randomly divided into four groups (5 mice/group). One group was treated with vemurafenib (25mg/kg/twice per day/oral gavage/4 weeks), one with IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/4 weeks, i.p.) and one with vemurafenib (25mg/kg/twice per day/oral gavage/4 weeks) in combination with IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/4 weeks, i.p.). One group of mice was left untreated as a reference for the natural course of the disease. Efficacy data are plotted as overall survival (OS) of the mice. The survival curve was plotted by Kaplan-Meier analysis. The number of mice at risk at each time point is also shown. B) M21 cells were implanted subcutaneously in 80 NSG mice. When tumors became palpable, mice were randomly divided into eight groups (10 mice/group): group 1 was treated with vemurafenib (25mg/kg/twice per day/oral gavage/2 weeks), group 2 with the IFNα-2b (100 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.), group 3 with vemurafenib (25mg/kg/twice per day/oral gavage/2 weeks) in combination with IFNα-2b (100 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.), group 4 with HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells (2x106 cells/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.v.) plus PEG-IL-2 (20 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.), group 5 with vemurafenib (25mg/kg/twice per day/oral gavage/2 weeks) in combination with HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells (2x106 cells/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.v.) and PEG-IL-2 (20 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.), group 6 with IFNα-2b (100 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.) in combination with HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells (2x106 cells/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.v.) and PEG-IL-2 (20 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.), group 7 with vemurafenib (25mg/kg/twice per day/oral gavage/2 weeks) in combination with IFNα-2b (100 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.) and HLA-A2-NY-ESO-1 peptide157-165-complex-specific T-cells (2x106 cells/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.v.) plus PEG-IL-2 (20 000 IU/injection/mouse, 3 times/week/2 weeks, i.p.). Group 8 of mice was left untreated as a reference for the natural course of the disease. Efficacy data are plotted as mean tumor volume of mice ± SD.

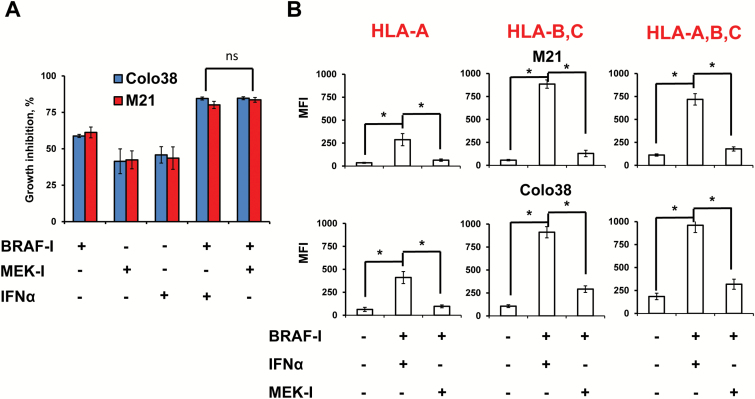

Antitumor Activity of BRAF-I and IFNα-2b Combination Compared With BRAF-I and MEK-I Combination in BRAFV600E Melanoma Cell Lines

The BRAF-I and IFNα-2b combination inhibited the in vitro growth of melanoma cells to a similar extent as the BRAF-I and MEK inhibitor (MEK-I) combination (Figure 8A). However, the BRAF-I and IFNα combination upregulated HLA class I antigens to a statistically significantly (P < .001) greater extent than the BRAF-I and MEK-I combination (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Antiproliferative and immunomodulatory activity of BRAF-I in combination with IFNα or MEK-I in BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines. A) BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38 and M21 were seeded at the density of 2.5x103 per well in a 96-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM) and/or IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/mL) and/or MEK-I trametenib (IC50). The IC50 of trametenib in M21 cells was 0.75nM while in Colo38 cells was 1.5nM (data not shown). Untreated cells were used as a control. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; vehicle of vemurafenib and trametenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, growth inhibition was determined by 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay. Data are expressed as percentage of growth inhibition ± SD of treated cells as compared with untreated cells. Percent of growth inhibition and SD were calculated from three independent experiments; each of them was performed in triplicate. B) BRAFV600E melanoma cell lines Colo38 and M21 were seeded at the density of 1x105 per well in a six-well plate and incubated with vemurafenib (500nM) and/or IFNα-2b (10 000 IU/mL) and/or MEK-I trametenib (IC50). Untreated cells were used as a control. DMSO (vehicle of vemurafenib) concentration was maintained at 0.02% in all wells. Following a 72-hour incubation at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, cells were harvested and cell surface stained with the indicated HLA class I antigen–specific mAbs. mAb MK2-23 was used as a specificity control. Cell staining was detected by R-PE-conjugated F(ab’)2 fragment goat antimouse IgG. Data are expressed as mean fluorescence intensity ± SD of the results obtained in three independent experiments. *Indicates P < .001. All P values were calculated using the two-sided Student’s t test.

Discussion

MAPK pathway activation induced by BRAFV600E has been shown to downregulate IFNAR1 both in cell lines and in melanoma tumors. The latter change is likely to reflect the ERK-mediated upregulation of βTrcp2/HOS protein, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that increases the ubiquitination and degradation of IFNAR1 (15). IFNAR1 expression both in cell lines and in patient-derived tumors is restored by BRAF-I, which causes inhibition of ERK activation (14). As a result, melanoma cells become more sensitive in vitro to IFNα’s antiproliferative, pro-apoptotic, and immunomodulatory activity. These in vitro findings provide a mechanism for the enhanced antitumor activity of IFNα when administered in combination with BRAF-I to immunodeficient mice grafted with BRAFV600E melanoma cells. If these results generated by in vitro experiments and in an mouse model system are predictive of results in patients with melanoma treated with BRAF-I and IFNα, then our findings have several clinical implications. First, optimal administration of IFNα, which is used in an adjuvant setting for high-risk resectable melanoma (11,12), requires selection of patients for lack of BRAF mutation in their melanoma tumors. Patients without BRAF mutation in their tumors are expected to do better than those with BRAFV600E. Second, this variable should be taken into account in the evaluation of clinical responses to IFNα administered to patients without selection for lack of BRAF mutation. Third, IFNα administration to patients harboring BRAFV600 mutations in their tumors should be combined with BRAF-I administration in order to increase the sensitivity of melanoma cells to the antitumor activity of IFNα.

In agreement with the information in the literature (26–29), we have found that IFNα increases HLA class I and HLA class II expression by melanoma cells. In addition, we show for the first time that IFNα upregulates the expression of most of the HLA class I APM components analyzed. This effect in conjunction with the increased expression of some of the MAs investigated has a functional relevance because, as previously described in a different experimental setting (29,30), the recognition of melanoma cells by cognate T-cells is statistically significantly increased. The immunomodulatory activity of IFNα is enhanced by BRAF-I. These results are likely to reflect not only the BRAF-I induced IFNAR1 upregulation but also the modulation by these two agents of the mechanisms that regulate HLA class I APM component and MA expression through distinct signaling pathways: STAT pathway activation by IFNα (11) and inhibition of MAPK pathway activation by BRAF-I (6-9,31). In addition, patients treated with BRAF-I and IFNα are expected to benefit from strategies that enhance the host’s T-cell immune response to his own tumor and/or from adoptive T-cell-based immunotherapy. In view of the current interest in the use of inhibitory checkpoint molecule-specific mAbs for the treatment of malignant diseases including melanoma, their administration is expected to enhance the therapeutic efficacy of BRAF-I and IFNα combination, especially if the mutated peptide(s) targeted by the host’s immune system is (are) derived from a protein(s) upregulated by BRAF-I and/or IFNα.

Induction of apoptosis appears to be one of the major mechanisms underlying the antitumor activity of IFNα (32). This effect is mediated by the STAT1 and STAT2 complex, which initiates gene transcription by binding to IFN-stimulated response elements (ISRE) (33). The pro-apoptotic activity of IFNα was markedly enhanced by BRAF-I, most likely because the BRAF-I-induced inhibition of MAPK activation eliminates the survival response of the cells exposed to IFNα. This interpretation is supported by the information in the literature (34,35) and our own results, that the inhibition of MAPK activation increases the sensitivity of melanoma cells to the pro-apoptotic activity of IFNα. However, this effect was counteracted at least in part by the persistence of an activated AKT in cells treated with BRAF-I and IFNα either as individual agents or in combination. We believe that this aberrant pathway activation might be an obstacle to the therapeutic efficacy of the BRAF-I and IFNα combination and therefore has to be counteracted in order to optimize its clinical use. Alternatively, given the lack of clinically useful PI3K/AKT inhibitors to be combined with BRAF-I because of the high associated toxicity, patients to be treated with the BRAF-I and IFNα combination should be selected for the lack of activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway in their melanoma tumors.

IFNα upregulated PD-L1 expression on M21 and SK-MEL-37 cells but did not induce its expression on Colo38 cells. On the other hand, BRAF-I exerted a differential effect either as an individual agent or in combination with IFNα. It enhanced PD-L1 expression on SK-MEL-37 cells, reduced it on M21 cells, and did not induce it on Colo38 cells. Whether patients carrying tumors without detectable PD-L1 expression even following exposure to IFNα will be more responsive to immunotherapy with BRAF-I and IFNα combination remains to be determined. Equally it remains to be determined whether CD44 induction on melanoma cells treated with BRAF-I and IFNα is associated with an increased aggressiveness because CD44 plays a role in their malignant phenotype and in their metastatic spread (36). An answer to these questions, as well as to the role of PI3K/AKT pathway activation in the clinical response to the BRAF-I and IFNα combination, may be provided by the two phase I-II clinical trials that are testing the toxicity and clinical response to BRAF-I and IFNα combination in patients with advanced melanoma (ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT01943422 and NCT01959633).

Lastly, in view of the recent approval by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) of the use of BRAF and MEK-I (37,38) for the treatment of BRAFV600E melanoma, the results we have obtained suggest that the BRAF-I and IFNα combination should be therapeutically more effective than BRAF-I and MEK-I combination if patients’ T-cell-based immune response against their own tumors plays an important role in the clinical course of the disease.

A limitation of this study is the lack of information about the effect of inhibition of AKT activation and PD-L1-PD-1 axis on the therapeutic efficacy of BRAF-I and IFNα combination. These questions are being addressed.

In conclusion, our study has provided a strong rationale to test the therapeutic efficacy of BRAF-I and IFNα combination in two currently recruiting clinical trials (ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT01943422 and NCT01959633). The implementation of these trials has been facilitated by the results we have obtained as well as by the availability of both BRAF-I and IFNα as FDA-approved drugs for the treatment of melanoma patients.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute (PHS grants RO1CA138188 and P50CA121973 to SF), by Fondazione Umberto Veronesi (Fondazione Umberto Veronesi Post Doctoral Fellowship by FS), by the Susan G. Komen for the Cure Foundation (Susan Komen Post Doctoral Fellowship KG111486 by YW), and by Centro per la Comunicazione e la Ricerca of the Collegio Ghislieri of Pavia (Research Fellowship by VV).

Supplementary Material

The study sponsors had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; the writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Keith T. Flaherty has a consultant/advisory role for GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and Roche. Paolo A. Ascierto has a consultant/advisory role for Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Roche-Genentech, and Ventana. He received a research grant from Roche-Genentech for the VEMUPLINT clinical study (NCT01959633); he received also drug supply from Merck Sharp & Dohme for the same clinical study. He received research grants from Bristol Myers Squibb and Ventana.

SF and FS developed the concept. SF, FS, WY, GB, and PAA designed the experiments. FS, YW, GS, EF, GP, and VV performed the experiments. FS, YW, GS, EF, ES, GP, AA, and GB analyzed the data. SAF provided unique reagents and analyzed the results. FS, SF, and CRF wrote the manuscript. SN and DG performed the statistical analysis of the results. KTF, PAA, SP, and CRF reviewed the data with special emphasis on the clinical aspects.

References

- 1. Chapman PB, Hauschild A, Robert C, et al. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(26):2507–2516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hauschild A, Grob JJ, Demidov LV, et al. Dabrafenib in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma: a multicentre, open-label, phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):358–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McArthur GA, Chapman PB, Robert C, et al. Safety and efficacy of vemurafenib in BRAF(V600E) and BRAF(V600K) mutation-positive melanoma (BRIM-3): extended follow-up of a phase 3, randomised, open-label study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(3):323–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wan PT, Garnett MJ, Roe SM, et al. Mechanism of activation of the RAF-ERK signaling pathway by oncogenic mutations of B-RAF. Cell. 2004;116(6):855–867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cohen C, Zavala-Pompa A, Sequeira JH, et al. Mitogen-actived protein kinase activation is an early event in melanoma progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(12):3728–3733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sapkota B, Hill CE, Pollack BP. Vemurafenib enhances MHC induction in BRAF homozygous melanoma cells. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2(1):e22890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boni A, Cogdill AP, Dang P, et al. Selective BRAFV600E inhibition enhances T-cell recognition of melanoma without affecting lymphocyte function. Cancer Res. 2010;70(13):5213–5219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mimura K, Kua LF, Shiraishi K, et al. Inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway can induce upregulation of human leukocyte antigen class I without PD-L1-upregulation in contrast to interferon-gamma treatment. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(10):1236–1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frederick DT, Piris A, Cogdill AP, et al. BRAF inhibition is associated with enhanced melanoma antigen expression and a more favorable tumor microenvironment in patients with metastatic melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(5):1225–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Liu J, Suresh Kumar KG, Yu D, et al. Oncogenic BRAF regulates beta-Trcp expression and NF-kappaB activity in human melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(13):1954–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Taniguchi T, Takaoka A. A weak signal for strong responses: interferon-alpha/beta revisited. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2(5):378–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Colamonici OR, Porterfield B, Domanski P, et al. Ligand-independent anti-oncogenic activity of the alpha subunit of the type I interferon receptor. J Biol Chem. 1994;269(44):27275–27279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mocellin S, Pasquali S, Rossi CR, et al. Interferon alpha adjuvant therapy in patients with high-risk melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(7):493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spiegelman VS, Tang W, Chan AM, et al. Induction of homologue of Slimb ubiquitin ligase receptor by mitogen signaling. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(39):36624–36630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kumar KG, Tang W, Ravindranath AK, et al. SCF(HOS) ubiquitin ligase mediates the ligand-induced down-regulation of the interferon-alpha receptor. EMBO J. 2003;22(20):5480–5490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee JH, Choi JW, Kim YS. Frequencies of BRAF and NRAS mutations are different in histological types and sites of origin of cutaneous melanoma: a meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(4):776–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002;417(6892):949–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Colombino M, Capone M, Lissia A, et al. BRAF/NRAS mutation frequencies among primary tumors and metastases in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2522–2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang X, Osada T, Wang Y, et al. CSPG4 protein as a new target for the antibody-based immunotherapy of triple-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2010;102(19):1496–1512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ogino T, Wang X, Ferrone S. Modified flow cytometry and cell-ELISA methodology to detect HLA class I antigen processing machinery components in cytoplasm and endoplasmic reticulum. J Immunol Methods. 2003;278(1–2):33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vermes I, Haanen C, Steffens-Nakken H, et al. A novel assay for apoptosis. Flow cytometric detection of phosphatidylserine expression on early apoptotic cells using fluorescein labelled Annexin V. J Immunol Methods. 1995;184(1):39–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sabbatino F, Wang Y, Wang X, et al. PDGFRalpha up-regulation mediated by sonic hedgehog pathway activation leads to BRAF inhibitor resistance in melanoma cells with BRAF mutation. Oncotarget. 2014;5(7):1926–1941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Robbins PF, Li YF, El-Gamil M, et al. Single and dual amino acid substitutions in TCR CDRs can enhance antigen-specific T cell functions. J Immunol. 2008;180(9):6116–6131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhao Y, Wang QJ, Yang S, et al. A herceptin-based chimeric antigen receptor with modified signaling domains leads to enhanced survival of transduced T lymphocytes and antitumor activity. J Immunol. 2009;183(9):5563–5574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Williams BR. Transcriptional regulation of interferon-stimulated genes. Eur J Biochem. 1991;200(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Angell TE, Lechner MG, Jang JK, et al. MHC Class I Loss is a Frequent Mechanism of Immune Escape in Papillary Thyroid Cancer that is Reversed by Interferon and Selumetinib Treatment in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(23):6034–6044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Garbe C, Krasagakis K, Zouboulis CC, et al. Antitumor activities of interferon alpha, beta, and gamma and their combinations on human melanoma cells in vitro: changes of proliferation, melanin synthesis, and immunophenotype. J Invest Dermatol. 1990;95(6 Suppl):231S–237S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nistico P, Tecce R, Giacomini P, et al. Effect of recombinant human leukocyte, fibroblast, and immune interferons on expression of class I and II major histocompatibility complex and invariant chain in early passage human melanoma cells. Cancer Res. 1990;50(23):7422–7429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maio M, Gulwani B, Langer JA, et al. Modulation by interferons of HLA antigen, high-molecular-weight melanoma associated antigen, and intercellular adhesion molecule 1 expression by cultured melanoma cells with different metastatic potential. Cancer Res. 1989;49(11):2980–2987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Greiner JW, Guadagni F, Noguchi P, et al. Recombinant interferon enhances monoclonal antibody-targeting of carcinoma lesions in vivo. Science. 1987;235(4791):895–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mimura K, Shiraishi K, Mueller A, et al. The MAPK pathway is a predominant regulator of HLA-A expression in esophageal and gastric cancer. J Immunol. 2013;191(12):6261–6272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Caraglia M, Dicitore A, Marra M, et al. Type I interferons: ancient peptides with still under-discovered anti-cancer properties. Protein Pept Lett. 2013;20(4):412–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Darnell JE, Jr., Kerr IM, Stark GR. Jak-STAT pathways and transcriptional activation in response to IFNs and other extracellular signaling proteins. Science. 1994;264(5164):1415–1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bruzzese F, Di Gennaro E, Avallone A, et al. Synergistic antitumor activity of epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor gefitinib and IFN-alpha in head and neck cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(2):617–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Caraglia M, Marra M, Viscomi C, et al. The farnesyltransferase inhibitor R115777 (ZARNESTRA) enhances the pro-apoptotic activity of interferon-alpha through the inhibition of multiple survival pathways. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(10):2317–2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dietrich A, Tanczos E, Vanscheidt W, et al. High CD44 surface expression on primary tumours of malignant melanoma correlates with increased metastatic risk and reduced survival. Eur J Cancer. 1997;33(6):926–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Larkin J, Ascierto PA, Dreno B, et al. Combined Vemurafenib and Cobimetinib in BRAF-Mutated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1867–1876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Long GV, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, et al. Combined BRAF and MEK Inhibition versus BRAF Inhibition Alone in Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(20):1877–1888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.