Significance

Our data suggest that the sudden rise in atmospheric temperature during the Paleocene–Eocene transition was not accompanied by highly elevated carbon dioxide concentrations >∼2,500 ppm. Instead, the low 13C/12C isotope ratios during the Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum were most likely caused by a significant contribution of methane to the atmosphere. We present data applying a newly developed partial pressure of CO2 proxy.

Keywords: PETM, temperature, CO2 concentration, mammals

Abstract

The Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) is a remarkable climatic and environmental event that occurred 56 Ma ago and has importance for understanding possible future climate change. The Paleocene–Eocene transition is marked by a rapid temperature rise contemporaneous with a large negative carbon isotope excursion (CIE). Both the temperature and the isotopic excursion are well-documented by terrestrial and marine proxies. The CIE was the result of a massive release of carbon into the atmosphere. However, the carbon source and quantities of CO2 and CH4 greenhouse gases that contributed to global warming are poorly constrained and highly debated. Here we combine an established oxygen isotope paleothermometer with a newly developed triple oxygen isotope paleo-CO2 barometer. We attempt to quantify the source of greenhouse gases released during the Paleocene–Eocene transition by analyzing bioapatite of terrestrial mammals. Our results are consistent with previous estimates of PETM temperature change and suggest that not only CO2 but also massive release of seabed methane was the driver for CIE and PETM.

The Paleocene–Eocene transition at about 56 Ma (1–3) is marked by an abrupt climate change in conjunction with a large negative carbon isotope excursion (CIE), ocean acidification, and enhanced terrestrial runoff—during a period lasting less than 220,000 y (e.g., refs. 4–7). During the CIE a global temperature increase of 5–8 °C has been inferred from a variety of marine and terrestrial proxies (e.g., refs. 3 and 8–21), hence the name “Paleocene–Eocene Thermal Maximum,” or PETM is frequently applied to the transition interval.

The CIE is well-documented by proxy data, and it is largely accepted that it was caused by the addition of a large amount of 13C-depleted carbon into the exogenic carbon cycle (ref. 22 and references therein). Considering the atmospheric CIE to be between –4 and –5‰ (ref. 22 and references therein and refs. 23 and 24), the suggested amount of carbon needed to cause this negative carbon isotope shift ranges between 2,200 and 153,000 Gt, a range depending on the isotope composition of the hypothesized carbon source and secondarily on the model approach used (22, 24–27). Possible carbon sources are biogenic methane (i.e., methane clathrates, δ13C ∼–60‰), thermogenic methane or permafrost soil carbon (δ13C ∼–30‰), carbon released due to wildfires or through desiccation and oxidation of organic matter due to drying of epicontinental seas (δ13C ∼–22‰), and mantle CO2 (δ13C ∼–5‰) (22, 28).

A massive release of methane clathrates by thermal dissociation (29) has been the most convincing hypothesis to explain the CIE since it was first identified. However, a methane clathrate source is still debated, and an involvement of other carbon sources—exclusively or additionally—is widely discussed (e.g., refs. 22, 26, and 28).

Global warming during the CIE is attributed to radiative forcing due to increased concentrations of greenhouse gases, most likely CO2 and/or CH4, and to accessory phenomena such as aerosol forcing and reduced cloudiness (26, 30).

Substantially different CO2 scenarios have been discussed for the PETM. Mass balance estimates range from an increase in atmospheric CO2 concentration of less than 100 ppm to an increase of several 10,000 ppm, depending on the proposed magnitude of the CIE and the associated carbon source (10, 22, 24, 25, 27, 31–34).

Existing proxy data for CO2 concentrations in the time interval surrounding the PETM (50–60 Ma) suggest background partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) levels between 100 and 1,900 ppm (ref. 35 and references therein). Only a single estimate (36) of the previously published data is questionably correlated to PETM strata (670 ppm).

From increased insect herbivory during the PETM Currano et al. (37, 38) suggested a three- to fourfold increase in atmospheric CO2 but left open the possibility that increased herbivory was an effect of higher insect diversity and density due to the elevated temperature.

Here we bring evidence to bear on both temperatures and CO2 concentrations through the Paleocene–Eocene transition based on triple oxygen isotope measurements (δ17O, δ18O) of bioapatite in mammalian tooth enamel.

The oxygen isotopic composition of mammalian body water is determined by its oxygen sources and sinks (Figs. S1 and S2). The main oxygen input sources for mammals are drinking water, food water, and inhaled air O2. Sinks are feces, sweat, water loss due to transpiration, as well as exhaled CO2 and moisture. The fractionation between δ18O of body water and δ18O of bioapatite in mammals is constant due to a constant body temperature of ∼37 °C, and it has been demonstrated that it is possible to relate the δ18O of mammalian bioapatite to the oxygen isotope composition of drinking water (i.e., environmental surface water, δ18OSW) by empirically developed calibration equations or by modeling approaches (39–44). Due to the strong correlation between δ18OSW and mean annual (air) temperatures (MAT) (45), it is in turn possible to infer paleotemperatures using the oxygen isotope composition of δ18OSW reconstructed from δ18O of mammalian bioapatite. This was first applied extensively by Bryant et al. (46). These studies rely solely on δ18O because, in nearly all terrestrial fractionation processes, δ18O is correlated to δ17O by the equation δ17O ≈ 0.52 × δ18O (e.g., ref. 47 and references therein).

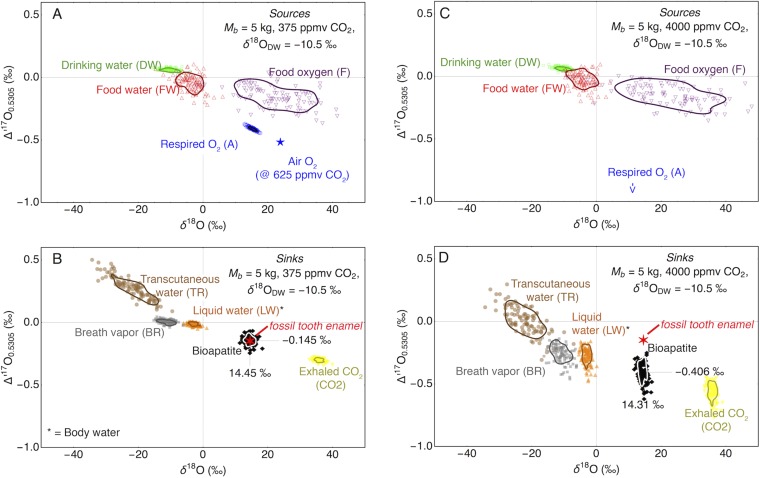

Fig. S1.

Plot of Δ17O vs. δ18O for sources (A) and sinks, BW, and bioapatite (B) for a scenario with 375 ppm CO2. The mass balance was calculated for Mb = 5 kg and model δ18ODW = –10.5 ‰. The ellipses outline the 1σ SD that was computed calculated by Monte Carlo simulation (n = 100). The uncertainties of the individual input parameters were taken from Pack et al. (50). The composition of fossil tooth enamel [sample E. osbornianus (Wa-2, locality SC-2), red star] is shown for comparison. (B and C) The same scenario as in A with an atmospheric CO2 mixing ratio of 4,000 ppm. The model bioapatite (D, black diamonds) has much lower Δ17O than the analyzed bioapatite (red star).

Fig. S2.

Mass balance calculation for enhanced water flow (2×, A and B and 4×, C and D) higher than inferred from the allometric scaling; all other parameters were the same as used in the model illustrated in Fig. S1). The main difference is the model δ18ODW, which increases with increasing FDW. This reflects the increasing dominance of drinking water as controlling factor for the isotope composition of BW and bioapatite.

However, air O2, which is one of the main oxygen sources of mammalian body water, carries an isotope anomaly in 17O (48) that is related to mass independent processes in the stratosphere. The isotope anomaly of inhaled air O2 is transferred to the body water and hence to mammalian bioapatite. The 17O anomaly of air O2 scales with atmospheric CO2 level and gross primary productivity (GPP) (49), and thus triple oxygen isotope analyses of bioapatite from fossil mammals can be used as a paleo-CO2 proxy (see ref. 50 for more details).

The magnitude of the 17O anomaly in mammalian bioapatite is connected to the fraction of inhaled anomalous air O2 in relation to the other oxygen sources. Due to higher specific metabolic rates (i.e., higher specific O2 respiration), smaller mammals carry a higher portion of anomalous oxygen in their bioapatite than larger mammals (50).

Studies relying on the relationship of paleotemperature to δ18O in mammalian bioapatite already exist for the Paleocene–Eocene transition in the Clarks Fork and Bighorn Basin (Wyoming) based on various mammalian taxa, targeting either the carbonate oxygen component (δ18OCO3) of mammalian tooth enamel, the phosphate oxygen component (δ18OPO4), or both in a combined approach (8, 17, 20, 21, 51–53).

In the present study, we combine this well-established δ18O paleothermometer (e.g., refs. 39 and 40) with the recently published discovery of a connection between the triple oxygen isotope composition of mammalian bioapatite and atmospheric CO2 concentration (50).

Materials and Methods

Samples.

The most suitable taxa for an application of the approach described above should have a body weight as small as possible (to ensure a high proportion of inhaled anomalous air oxygen in respect to the other oxygen sources) but large enough (with respect to fossil samples) to provide an adequate amount of diagenetically unaltered sample material (i.e., tooth enamel) (e.g., refs. 54 and 55).

We sampled tooth enamel from teeth from jaws and isolated teeth of 11 individual specimens of the phenacodontid genus Ectocion (Ectocion osbornianus and Ectocion parvus) from the Clarks Fork Basin (Sand Coulee area) in northwestern Wyoming (e.g., refs. 56 and 57). The enamel was carefully hand-picked under a binocular microscope before pretreatment. The samples cover a time interval of several mammalian biozones, from the late Clarkforkian (Cf-3) to the early Wasatchian (Wa-2), encompassing the PETM. All samples were acquired from the collections of the Museum of Paleontology at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor (localities SC-2, SC-11, SC-67, SC-107, SC-138, and SC-161). All were molded and cast before destructive sampling. Only second molars (M2) were used for the present study to obtain the highest possible comparability.

Sample Pretreatment.

To ensure analysis was limited to the phosphate oxygen isotope composition (δ18OPO4), other oxygen-bearing components of the sample material (e.g., organic matter, sorbed water, structural carbonate, and OH– groups) were removed by treating the tooth enamel in an Ar-flushed horizontal tube furnace for 10–15 min at 1,000 °C. Subsequently, the samples were cooled to below 100 °C while remaining in an Ar atmosphere, followed by immediate storage in a desiccator until analysis (50). This procedure follows Lindars et al. (58), who demonstrated safe removal of all of the unwanted compounds at temperatures between 850 and 1,000 °C. Ar is used to avoid exchange with atmospheric water, which was reported to be a problem by Lindars et al. (58) when heating samples to 1,000 °C in ambient air.

Triple Oxygen Isotope Analysis.

Variations in the oxygen isotope ratios (17O/16O, 18O/16O) are reported relative to the international isotope reference standard Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water 2 in the form of the δ17O and δ18O notation (59). In mass-dependent (equilibrium or kinetic) fractionation processes, variations in δ17O broadly correlate with variations in δ18O. To better display small deviations from an otherwise good correlation, the Δ17O value has been introduced. We follow the definition scheme for Δ17O as presented in Pack and Herwartz (60) with Δ17O = 1,000*ln(δ18O/1,000 + 1) – 0.5305*1,000*ln(δ18O/1,000 + 1). The Δ17O has been normalized to a revised composition of NBS 28 quartz with δ17O = 5.03‰ and δ18O = 9.60‰ (Δ17O = −0.05‰).

A slope derived from analytical data of terrestrial rocks and minerals as done in previous studies (50, 55) has not been used because of its arbitrary selection depending on the specific samples analyzed to obtain it. However, the data can easily be converted for comparison with results from other studies and/or other laboratories.

Oxygen was released from the samples by infrared laser fluorination (61) and analyzed by gas chromatography isotope ratio monitoring gas mass spectrometry in continuous flow mode (e.g., refs. 50, 55, and 62). Typically, ∼0.3 mg of pretreated fossil tooth enamel was loaded into an 18-pit polished Ni sample holder along with ∼0.3 mg of pretreated tooth enamel from a modern African Elephant (Loxodonta africana) as an internal standard and ∼0.2 mg NBS 28 quartz. Following evacuation and heating of the sample chamber to 70 °C for at least 12 h, fluorination was implemented by heating the samples with a SYNRAD 50 W CO2 laser in a ∼20–30 mbar atmosphere of F2 gas, purified according to Asprey (63). Liberated excess F2 was reacted with heated NaCl (∼180 °C) to NaF and Cl2. The latter was cryotrapped by liquid N2 until all samples were analyzed. Sample O2 was cryofocused on a molecular sieve trap at –196 °C (liquid N2) then expanded into a stainless steel capillary and transported with He as carrier gas through a second molecular sieve trap, where a fraction of the sample gas was again cryofocused at –196 °C. After releasing this back into the He carrier gas stream by heating it in a hot water bath (∼92 °C), the sample O2 was purified by passing it through a 5-Å molecular sieve GC column of a Thermo Scientific GasBench II and then injected via an open split valve of the GasBench II into the source of a Thermo MAT 253 gas mass spectrometer. The signals of 16O16O, 17O16O, and 18O16O were simultaneously monitored on three Faraday cups. Reference O2 was injected before each sample measurement through a second open split valve of the GasBench II. Sample and reference gas peaks (m/z = 32) had an amplitude of 20–30 V.

The SD for replicates of the same bioapatite samples from different runs is typically better than ±0.5‰ in Δ18O and ± 0.04‰ in Δ17O for a single analysis.

A total of 72 single laser fluorination analyses were made using 14 different Ectocion tooth enamel samples (from the 11 Ectocion specimens used for the present study, 3 were sampled twice to have a reproducibility control between different analytical runs) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Oxygen isotope composition (δ18OPO4, Δ17OPO4) of tooth enamel from second molars of Ectocion osbornianus and Ectocion parvus from the Clarks Fork Basin in north-western Wyoming

| Species | Biozone | Level, m | Locality | Sample no. | δ18OPO4, ‰ | Δ17OPO4, ‰ | N | pCO2 (model), ppm by volume | pCO2 (model, 2.3× GPP), ppm by volume | ||

| E. osbornianus | Wa-2 | 1,720 | SC-2 | 85906 | 13.0 ± 0.4 | −0.17 ± 0.04 | 5 | 500 | −400 +600 | 1,150 | −1,000 +1,400 |

| E.osbornianus | Wa-2 | 1,720 | SC-2 | 66572 (sample A) | 12.4 ± 0.3 | −0.18 ± 0.02 | 8 | 625 | −400 +600 | 1,440 | −1,000 +1,400 |

| E.osbornianus | Wa-2 | 1,720 | SC-2 | 66572 (sample B) | 13.0 ± 0.5 | −0.19 ± 0.03 | 7 | 750 | −400 +600 | 1,730 | −1,000 +1,400 |

| Mean | 12.8 ± 0.2 | -0.18 ± 0.02 | 20 | 630 | −230 +350 | 1,450 | −500 +800 | ||||

| E.osbornianus | Wa-2 | 1,665 | SC-161 | 80705 | 13.5 ± 0.4 | −0.14 ± 0.02 | 3 | 225 | −200 +400 | 520 | −500 +1,000 |

| E.osbornianus | Wa-2 | 1,665 | SC-161 | 98404 | 13.2 ± 0.3 | −0.13 ± 0.03 | 4 | 200 | −200 +400 | 460 | −500 +1,000 |

| E.osbornianus | Wa-2 | 1,665 | SC-161 | 68200 | 12.3 ± 0.3 | −0.15 ± 0.03 | 4 | 250 | −250 +500 | 580 | −600 +1,200 |

| Mean | 13.0 ± 0.2 | -0.14 ± 0.02 | 11 | 230 | −200 +320 | 530 | −460 +750 | ||||

| E.parvus | Wa-0 | 1,520 | SC-67 | 83478 | 14.3 ± 0.3 | −0.15 ± 0.04 | 2 | 250 | −200 +400 | 580 | −500 +1,000 |

| E.parvus | Wa-0 | 1,520 | SC-67 | 87354 | 14.3 ± 0.6 | −0.18 ± 0.03 | 5 | 625 | −400 +600 | 1,440 | −1,000 +1,400 |

| E.parvus | Wa-0 | 1,520 | SC-67 | 86572 (sample A) | 15.1 ± 0.2 | −0.17 ± 0.03 | 7 | 625 | −400 +600 | 1,440 | −1,000 +1,400 |

| E.parvus | Wa-0 | 1,520 | SC-67 | 86572 (sample B) | 14.4 ± 0.3 | −0.15 ± 0.03 | 2 | 250 | −200 +400 | 580 | −500 +1,000 |

| Mean | 14.5 ± 0.2 | -0.16 ± 0.02 | 16 | 440 | −160 +250 | 1,010 | −400 +600 | ||||

| E.osbornianus | Cf-3 | 1,502 | SC-107 | 66621 | 11.0 ± 0.5 | −0.14 ± 0.03 | 11 | 250 | −250 +500 | 580 | −600 +1,200 |

| E.osbornianus | Cf-3 | 1,495 | SC-138 | 67243 (sample A) | 13.7 ± 0.3 | −0.16 ± 0.03 | 7 | 500 | −400 +500 | 1,150 | −1,000 +1,200 |

| E.osbornianus | Cf-3 | 1,495 | SC-138 | 67243 (sample B) | 13.8 ± 0.6 | −0.19 ± 0.05 | 4 | 825 | −400 +600 | 1,900 | −1,000 +1,400 |

| E.osbornianus | Cf-3 | 1,485 | SC-11 | 64726 | 12.1 ± 0.3 | −0.14 ± 0.02 | 3 | 225 | −200 +500 | 520 | −500 +1,200 |

| Mean | 12.7 ± 0.2 | −0.16 ± 0.02 | 25 | 450 | −200 +260 | 1,040 | −450 +600 | ||||

The reported pCO2 data were calculated for modern gross primary productivity (GPP) and 2.3× elevated GPP on basis of the mass balance model (for details, see Supporting Information). Uncertainty estimates are ±1σ SD.

Results and Discussion

Temperature Change Across the PETM Inferred from δ18O of Ectocion Tooth Enamel.

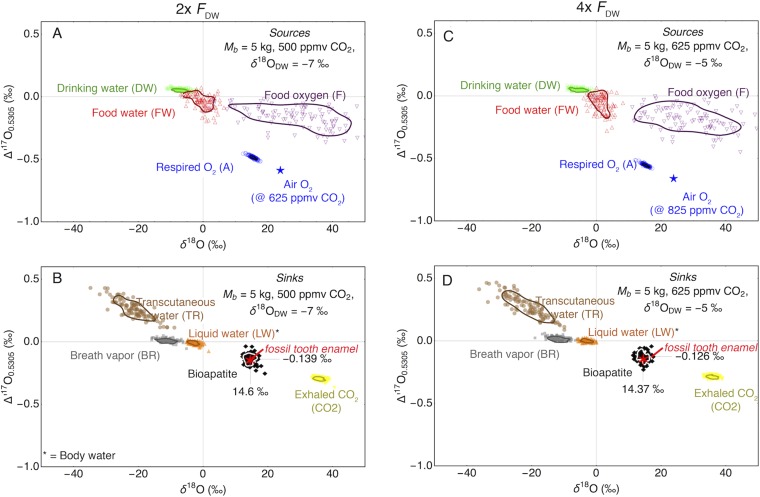

The mean oxygen isotope composition of tooth enamel phosphate (δ18OPO4) in the Ectocion specimens investigated increases by 2.2‰ from the late Clarkforkian (Cf-3) to the CIE in the early Wasatchian (Wa-0), considering the mean values for each mammalian biozone. From Wa-0 to Wa-2, a decrease in mean δ18OPO4 of 1.6‰ is observed (different meter levels within Wa-2 do not show any difference in δ18OPO4, so they were combined (Fig. 1 and Tables 1 and 2). This is in agreement with previous results from δ18OPO4 (17, 20), as well as δ18OCO3 (17, 20, 21) for mammals covering the same biozones in the same study area. To estimate the change of δ18OSW from δ18OPO4, we used the relationship for modern herbivorous mammals (δ18OSW = 1.32 × δ18OPO4), which Secord et al. (20) adapted from Kohn et al. (64).

Fig. 1.

Oxygen isotope composition (δ18OPO4, ±1σ SD) of Ectocion (white squares, this study; Table 1), Phenacodus [gray diamonds; Secord et al. (20)], and Coryphodon specimens [gray squares; Fricke et al. (17)]. Red circles are mean values for Ectocion (this study). Missing error bars indicate single analyses. The stratigraphic level is expressed in meters above the K-T boundary in the Clarks Fork Basin. Age of Ectocion samples is in the range of −56 to −55 Ma (see Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Estimated change in δ18OSW and temperature at the Paleocene–Eocene transition in the Clarks Fork and Bighorn Basin

| Biozone interval | Δ18OPO4, ‰ | Δ18OSW, ‰ | ΔT (0.58‰/°C) | ΔT (0.39‰/°C) | ΔT (0.36‰/°C) |

| This study | |||||

| Wa-0 to Wa-2 | −1.6 | −2.1 | −3.6 | −5.4 | −5.8 |

| Cf-3 to Wa-0 | +2.2 | +2.9 | +5.0 | +7.4 | +8.1 |

| Secord et al. (20) | |||||

| Cf-3 to Wa-0 | +2.1 | +2.8 | +4.8 | +7.2 | +7.8 |

| Fricke et al. (17) | |||||

| Wa-0 to Wa-3a | −1.4 | −1.8 | −3.1 | −4.6 | −5.0 |

| Cf-2 to Wa-0 | +1.8 | +2.4 | +4.1 | +6.2 | +6.7 |

Applying this to our results, δ18OSW became enriched by 2.9‰ from Cf-3 to Wa-0 followed by a depletion of 2.1‰ to Wa-2 (Table 2).

The δ18OSW/MAT slope is sensitive to the latitudinal gradient and other factors (e.g., ref. 65), so an important precondition for estimating the corresponding change in temperature is to adjust this slope as closely as possible to early Cenozoic conditions. The modern temperature dependence for a MAT of 0–20 °C ranges between 0.5 and 0.6‰ per degree Celsius (66–68). During the Paleocene–Eocene transition in the Bighorn Basin, Secord et al. (20) proposed δ18OSW/MAT slopes of 0.39 and 0.36 (per mille per degree Celsius), based on two different approaches.

For the Ectocion tooth enamel data of the present study, this implies an increase of 7.4 °C (8.1 °C) from Cf-3 to Wa-0 and a decrease of 5.4 °C (5.8 °C) from Wa-0 to Wa-2 (the value in parentheses refers to the slope for 0.36). These results are in general agreement with previous studies from Fricke et al. (17) and Secord et al. (20) based on tooth enamel δ18OPO4 of Coryphodon and Phenacodus, respectively. Calculated on the same basis, the data from Fricke et al. (17) indicate a temperature increase of 6.2 °C (6.7 °C) from Cf-2 to Wa-0 and a decrease of 4.6 °C (5.0 °C) from Wa-0 to Wa-3. The data from Secord et al. (20) suggest a temperature increase of 7.2 °C (7.8 °C) from Cf-3 to Wa-0, if mean biozone values are used (Table 2).

Atmospheric CO2 Levels Across the PETM Inferred from δ17O of Ectocion Tooth Enamel.

Tooth enamel of the investigated Ectocion specimens has a distinctly negative 17O anomaly, with Δ17O ranging between –0.19 and –0.13‰ (Table 1). The anomaly is due to the portion of oxygen in the bioapatite that comes from inhaled isotopically anomalous air O2 (50). To estimate the Δ17O of PETM air oxygen from the tooth enamel measurements, we used the oxygen mass balance model of Pack et al. (50), developed for terrestrial herbivorous mammals (for details see Supporting Information). The body weights of E. osbornianus and E. parvus are estimated to have been 9 and 5 kg, respectively (e.g., refs. 69 and 70).

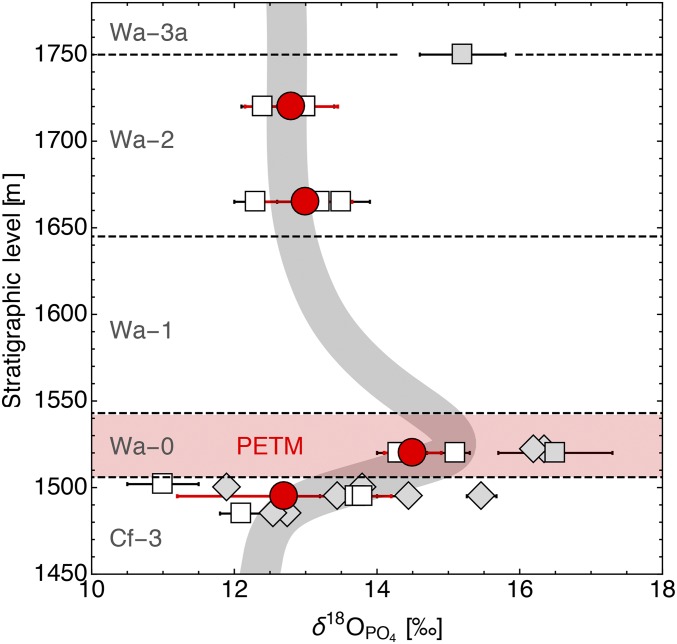

Combining the approach of Pack et al. (50) with the linear relationship between Δ17Oair and pCO2 given by Bao et al. (49), the estimated mean pCO2 values are 450, 440, 230, and 630 ppm for Cf-3 (1,485- to 1,502-m level), Wa-0 (1,520-m level), Wa-2 (1,665-m level), and Wa-2 (1,720-m level), respectively (Fig. 2A and Table 1). The uncertainty estimate is in the range of ± several hundred ppm. However, these numbers are based on modern O2 and GPP conditions. Whereas pO2 remains more or less unchanged within the last 60 Ma (71), a considerably different GPP of 2.3 times the modern value has been estimated by Beerling (72) for the early Eocene. Because a doubling of GPP results in a halving of Δ17Oair (49, 50), a 2.3 GPP would imply pCO2 mean values of 1,040, 1,010, 530, and 1,450 ppm for Cf-3 (1,485- to 1,502-m level), Wa-0 (1,520-m level), Wa-2 (1,665-m level), and Wa-2 (1,720-m level), respectively (Fig. 2B and Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Existing proxy data for pCO2 between 50 and 60 Ma adapted from the compilation of Beerling and Royer (35), compared with pCO2 estimates from Δ17O of Ectocion bioapatite (red circles, this study). pCO2 has been calculated for (A) modern global GPP conditions and (B) GPP 2.3 times the modern value, as proposed by Berner (71). White diamonds, paleosols; gray squares, leaf stomata; white squares, marine phytoplankton; gray diamonds, liverworts. pCO2 results here are the first to our knowledge to come unquestionably from the PETM interval. Note that pCO2 results for the PETM here are not elevated but consistent with earlier and later pCO2 values reported by Beerling and Royer (35).

The results for the modern GPP scenario agree well with other proxy data for the time slice between 50 and 60 Ma from δ13C of paleosols (1, 36, 73), leaf stomata (36, 74–76), and δ13C of marine phytoplankton (77), which nearly all range between 300 and 800 ppm (Fig. 2B). A few paleosol estimates propose a considerably lower pCO2 of ∼100 ppm [ref. 78, reevaluated by Breecker et al. (73)], and a single estimate from δ13C of fossil liverworts (79) suggests a considerably higher pCO2 of ∼1,900 ppm for the Early Eocene.

Following Beerling and Royer (35), Paleocene and Eocene pCO2 estimates from δ11B of planktonic foraminifera were not considered for the present comparison due to several uncertainties (e.g., regarding diagenetic alteration and unknown vital effects of the analyzed foraminifera). Geochemical modeling (GEOCARBSULFvolc, refs. 80–82) predicts slightly higher pCO2 than nearly all proxy results. However, the low resolution (10-Ma time steps) precludes tracking pCO2 fluctuations within shorter time intervals.

Nearly all previously published proxy data represent either pre- or post-PETM estimates of pCO2. Only Royer et al. [ref. 36, updated by Beerling et al. (76); compare also Beerling and Royer (35)] report a single stomatal index estimate revised to 670 ppm. This estimate is based on material from the Isle of Mull, United Kingdom, which was initially stated to correlate potentially to the PETM, within a data series of slightly older late Paleocene and younger early Eocene pCO2 estimates ranging between 300 and 570 ppm.

Thus, the pCO2 data presented here from the Wa-0 biozone, which to our knowledge are the first to track CO2 levels directly through the CIE and PETM, are of particular interest and provide independent information on the potential carbon source generating the CIE.

Even when considering the large uncertainty in pCO2 and a 2.3 times higher bioproductivity than today, all mean biozone estimates suggest a peak pCO2 (upper error limit) not higher than about 2,500 ppm before and during the PETM and CIE, from Cf-3 to the start of Wa-2 (Fig. 2B and Table 1).

In the spectrum of pCO2 values associated with different carbon sources considered as generating a global CIE in a range of –4 to –5‰, our results are compatible with dissociation of ∼2,500 to ∼4,500 Gt of highly 13C-depleted marine methane clathrates, as initially proposed by Dickens et al. (29), which would require only a moderate pCO2 increase (e.g., refs. 22, 24, and 27).

The model of Zeebe et al. (27) requires an increase in pCO2 from a pre-PETM 1,000 ppm baseline to ∼1,700 ppm during the PETM main phase, based on an initial input of 3,000 Gt C from methane clathrates with a δ13C lighter than –50‰. Furthermore, Zeebe et al. (27) claim that this 70% increase in pCO2 is largely independent from the initial pre-PETM pCO2, arguing for an increase from 500 to ∼850 ppm as likewise possible. A similar result was obtained by Cui et al. (24) when 2,500 Gt C from methane clathrates with a δ13C of –60‰ was assumed as the potential carbon source (increase in pCO2 from a baseline of 835 ppm to ∼1,500 ppm). In addition, the mass balance presented by McInerney and Wing (22) estimated a pCO2 increase to ∼1,500 ppm, potentially triggered by a release of 4,300 Gt C from methane clathrates required to generate a CIE of –4.6‰. In a recent approach, Schubert and Jahren (83) calculated initial and peak-PETM CO2 levels using the difference between the magnitude of the marine and terrestrial CIE (ΔCIE) and proposed a pCO2 increase from 670 to 1,380 for the methane clathrate scenario.

All other sources in discussion for the CIE (thermogenic methane, permafrost soil carbon, carbon released due to wildfires or through desiccation and oxidation of organic matter due to drying of epicontinental seas as well as mantle CO2) would have led to significantly higher CO2 levels than suggested by our results.

If the observed CIE would have been induced by the release of thermogenic methane or permafrost soil carbon (10,000 Gt C, δ13C ∼–30‰), McInerney and Wing (22) proposed a pCO2 increase to ∼3,000 ppm. Using ΔCIE, Schubert and Jahren (83) calculated an increase from 920 to 2,480 ppm until the peak of the PETM for this scenario (Fig. 2). Such a scenario would still be within the uncertainty range of our data and cannot be completely excluded here.

Higher pCO2 estimates have been proposed for carbon input from wildfires and/or desiccation and oxidation of organic matter from drying epicontinental seas (with a δ13C of ∼–22‰). The mass balance of McInerney and Wing (22) suggests CO2 levels >4,000 ppm induced by a release of ∼15,400 Gt of carbon. This is nearly identical to the model of Cui et al. (24), who proposed a release of 13,000 Gt C from the same source, resulting in a pCO2 increase from 835 to 4,200 ppm. The proposed CO2 concentrations are considerably higher than estimated from the present study.

An alternative model (25) suggests a minimum pulse of carbon with a δ13C of –22‰ to be 6,800 Gt to trigger a CIE of –4‰, associated to an increase in pCO2 to levels considerably above 2,000 ppm. The approach of Schubert and Jahren (83) suggests for the same carbon sources an increase from an initial value of 1,030 ppm to 3,340 ppm atmospheric CO2 during the PETM.

Thus, the present study supports the initial idea of Dickens et al. (29) that massive releases of methane from clathrates caused the positive temperature excursion and the CIE during the PETM, at least to a considerable amount. Some criticisms to the methane clathrate scenario proposed in the last decade have turned out to be poorly constrained. One widely discussed argument is that pCO2 values associated with the methane clathrate hypothesis are insufficient to explain the PETM temperature increase. However, alternative mechanisms, such as direct radiative forcing due to an increased pCH4, and associated indirect effects (26, 27, 30, 31) may overrule this objection. The assumption that early Paleogene methane clathrate reservoirs were too small (84) has recently been discredited (26, 85). The idea that the amount of carbon released from methane clathrates would have been insufficient to explain observed shoaling of the carbonate compensation depth (86) has also been criticized (26). A massive release of CO2 from soils, wildfires, or by oxidation of organic matter from drying epicontinental seas is not supported by the results of this study.

Conclusions

Triple oxygen isotope analysis of fossil mammalian bioapatite has the potential to trace fluctuations in temperature and CO2 levels simultaneously, representing a powerful new tool for paleoclimatological research. Our Ectocion bioapatite data agree well with previous estimates of temperature change from the oxygen isotope composition of mammalian tooth enamel and from other proxies across the Paleocene–Eocene transition. Our results support existing proxy data for late Paleocene and early Eocene pCO2. Our samples originate directly from pre-, peak- and post-PETM/CIE strata, making it possible for the first time to our knowledge to recognize any substantial change in CO2 concentration within the respective time interval. Our data suggest that CO2 levels during the PETM/CIE remained, within uncertainty of a few hundreds of parts per million, at pre- and post-PETM/CIE levels. Our data hence support the hypothesis that the CIE was mainly caused by a massive release of seabed methane to the atmosphere, and carbon emissions from other sources have made a subordinate contribution.

Oxygen Mass Balance Model

The mass balance model used in this study is based on the model presented in Pack et al. (50). The following in and out fluxes Fi were considered:

-

•

Sources

o FDW: Drinking water

o FA: Respired air O2

o FFW: Moisture in food

o FF: Oxygen bond in carbohydrates, fats, and proteins

-

•

Sinks

o FLW: Liquid water in excrements

o FCO2: Oxygen in exhaled CO2

o FTR: Transcutaneous water loss

o FBR: Vapor loss in breath

The fluxes (moles of O2 per day) were taken from Pack et al. (50). The steady-state oxygen isotope composition of body water (BW) is given by

with

The isotope compositions of the influxes (FDW, FA, FFW, and FF) are independent of the composition of the BW. The isotope compositions of the outfluxes (FLW, FCO2, FTR, and FBR) are function of δ17,18OBW and the fractionation associated with the outflux with

The fractionation factor α17 for 17O/16O is related to the fractionation factor α18 for 18O/16O by the triple isotope fractionation exponent θ with

The Δ17O of any flux Fi and BW is then calculated from the individual δ17Oi–δ18Oi pairs. The composition of the bioapatite is assumed to be in equilibrium with BW at a temperature of 37 °C (see ref. 50 for details).

The only anomalous component is air O2 with negative Δ17O. Several studies have been undertaken to determine the Δ17Ο of tropospheric O2 (87–91). The reported Δ17O values vary between −566 (89) and −432 ppm (91). The anomaly in Δ17O scales with the atmospheric CO2 mixing ratio (49) and is an important input parameter for this study. We have extracted O2 from air following a protocol similar to that described by Young et al. (91). We obtained Δ17O = −469 ppm for air O2, which is in good agreement with the data reported by Thiemens et al. (−462 ppm) (87), and Young et al. (91) normalized to the revised Δ17O of San Carlos olivine of −51 ppm (−460 ppm). For this study we adopt a value of Δ17O = −465 ppm for air O2. This value is tied to the preindustrial CO2 mixing ratio of 270 ppm by volume.

Because of the restricted body mass Mb range in this study (5 and 9 kg), allometric scaling for the total water flux (FTW; data from ref. 92) and field metabolic rates (FMR; data from ref. 93) were calculated from data with 1 kg ≤ Mb ≤ 10 kg (FTW = 3.520 Mb0.787 mol O2⋅d–1) and 0.1 kg ≤ Mb ≤ 10 kg (FMR = 1.434 Mb0.638 mol O2⋅d–1).

Examples for the results of the mass balance are given in Figs. S1 and S2.

For the pre- and post-PETM fossils, the mass balance model gives δ18ODW is −14.8‰. During the PETM (Wa-0), an elevated mean model δ18ODW of −10.5‰ is calculated (Fig. S1B). This is slightly lower than the range of −12 to −8‰ suggested by Koch et al. (21) but higher than suggested by measurements of soil hematite by Bao et al. (94). The discrepancy between our model δ18ODW data and the suggested meteoric water data by Koch et al. (21) could be interpreted in terms of a higher FDW/FA flux ratio (FDW and FA are the main oxygen sources in mammals). This would lead to a dilution of the anomalous oxygen isotope signal and erroneously low pCO2 estimates. We thus calculated the pCO2 for a two- and fourfold increased intake of drinking water (FDW) (Fig. S2).

The model with 1× FDW gives 375 ppm CO2 (Fig. S1). For elevated drinking water fluxes (2× and 4×; Fig. S2), elevated CO2 concentrations of 500 and 625 ppm are inferred from the model. Dilution of the isotope anomaly of respired air O2 by isotopically normal drinking water leads to an underestimate of the atmospheric CO2 mixing ratios. The effect of a fourfold increased water flux, however, is still within the uncertainty limits given for a scenario with average (in this case for mammals of Mb = 5 kg) FDW. The scenario with 4× enhanced drinking water flux, however, gives a δ18ODW = –5 ‰, which is higher than suggested for the Bighorn Basin during the Eocene/Paleocene boundary (21, 94). Higher FDW will give even higher δ18O values for the meteoric water. From these results we conclude that the E. parvus likely had a water balance typical of the average land-living mammal.

Acknowledgments

We thank N. Albrecht, A. Höweling, C. Seidler, and M. Troche for assistance during sample pretreatment and isotope analysis; Verena Bendel for technical assistance in data analysis; Vanessa Roden, Wiebke Kallweit, and Tanja Stegemann for careful proofreading; and Reinhold Przybilla for technical support on the mass spectrometry line. A.G. was supported by German National Science Foundation Grant PA909/5-1 (to A.P.). Specimens analyzed here were collected with support from National Science Foundation Grant EAR-0125502 (to P.D.G.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1518116113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Koch P, Zachos JC, Gingerich PD. Correlation between isotope records in marine and continental carbon reservoirs near the Palaeocene/Eocene boundary. Nature. 1992;358:319–322. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Westerhold T, Röhl U, McCarren HK, Zachos JC. Latest on the absolute age of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM): New insights from exact stratigraphic position of key ash layers +19 and -17. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2009;287(3):412–419. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kennett JP, Stott LD. Abrupt deep sea warming, palaeoceanographic changes and benthic extinctions at the end of the Palaeocene. Nature. 1991;353:225–229. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aziz HA, et al. Astronomical climate control on paleosol stacking patterns in the upper Paleocene-lower Eocene Willwood Formation, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Geology. 2008;36(7):531–534. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Röhl U, Westerhold T, Bralower TJ, Zachos JC. On the duration of the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) Geochem Geophys Geosyst. 2007;8(12):Q12002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy BH, Farley KA, Zachos JC. An extraterrestrial 3He-based timescale for the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM) from Walvis Ridge, IODP Site 1266. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2006;74(17):5098–5108. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farley KA, Eltgroth SF. An alternative age model for the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum using extraterrestrial 3He. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2003;208(3):135–148. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fricke HC, Wing SL. Oxygen isotope and paleobotanical estimates of temperature and δ18O-latitude gradients over North America during the early Eocene. Am J Sci. 2004;304(7):612–635. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, Thomas E, Billups K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science. 2001;292(5517):686–693. doi: 10.1126/science.1059412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zachos JC, et al. A transient rise in tropical sea surface temperature during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Science. 2003;302(5650):1551–1554. doi: 10.1126/science.1090110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tripati A, Elderfield H. Deep-sea temperature and circulation changes at the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Science. 2005;308(5730):1894–1898. doi: 10.1126/science.1109202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zachos JC, et al. Extreme warming of mid-latitude coastal ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: Inferences from TEX86 and isotope data. Geology. 2006;34(9):737–740. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas DJ, Zachos JC, Bralower TJ, Thomas E, Bohaty S. Warming the fuel for the fire: Evidence for the thermal dissociation of methane hydrate during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Geology. 2002;30(12):1067–1070. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sluijs A, et al. Expedition 302 Scientists Subtropical Arctic Ocean temperatures during the Palaeocene/Eocene thermal maximum. Nature. 2006;441(7093):610–613. doi: 10.1038/nature04668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weijers JWH, Schouten S, Sluijs A, Brinkhuis H, Sinninghe Damsté JS. Warm arctic continents during the Palaeocene–Eocene thermal maximum. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2007;261(1):230–238. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowen GJ, et al. 2001. Refined isotope stratigraphy across the continental Paleocene-Eocene boundary on Polecat Bench in the northern Bighorn Basin. Paleocene-Eocene Stratigraphy and Biotic Change in the Bighorn and Clarks Fork Basins, Wyoming, University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology, ed Gingerich PD (Museum of Paleontology, Univ of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), Vol 33, pp 73–78.

- 17.Fricke HC, Clyde WC, O’Neil JR, Gingerich PD. Evidence for rapid climate change in North America during the latest Paleocene thermal maximum: Oxygen isotope compositions of biogenic phosphate from the Bighorn Basin (Wyoming) Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1998;160(1):193–208. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch PL, et al. Carbon and oxygen isotope records from paleosols spanning the Paleocene-Eocene boundary, Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Spec Pap Geol Soc Am. 2003;369:49–64. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wing SL, et al. Transient floral change and rapid global warming at the Paleocene-Eocene boundary. Science. 2005;310(5750):993–996. doi: 10.1126/science.1116913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Secord R, Gingerich PD, Lohmann KC, Macleod KG. Continental warming preceding the Palaeocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Nature. 2010;467(7318):955–958. doi: 10.1038/nature09441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koch P, Zachos JC, Dettmann DL. Stable isotope stratigraphy and paleoclimatology of the Paleogene Bighorn Basin (Wyoming, USA) Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1995;115(1):61–89. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McInerney FA, Wing SL. The Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum: A perturbation of carbon cycle, climate, and biosphere with implications for the future. Annu Rev Earth Planet Sci. 2011;39:489–516. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diefendorf AF, Mueller KE, Wing SL, Koch PL, Freeman KH. Global patterns in leaf 13C discrimination and implications for studies of past and future climate. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(13):5738–5743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910513107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cui Y, et al. Slow release of fossil carbon during the Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Nat Geosci. 2011;4(7):481–485. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Panchuk K, Ridgwell A, Kump LR. Sedimentary response to Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum carbon release: A model-data comparison. Geology. 2008;36(4):315–318. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dickens GR. Down the rabbit hole: Toward appropriate discussion of methane release from gas hydrate systems during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum and other past hyperthermal events. Clim Past. 2011;7(3):831–846. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeebe R, Zachos JC, Dickens GR. Carbon dioxide forcing alone insufficient to explain Palaeocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum warming. Nat Geosci. 2009;2(8):576–580. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins JA, Schrag DP. Beyond methane: Towards a theory for the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2006;245(3):523–537. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickens GR, O’Neil JR, Rea DK, Owen RM. Dissociation of oceanic methane hydrate as a cause of the carbon isotope excursion at the end of the Paleocene. Paleoceanography. 1995;10(6):965–971. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kurtén T, et al. Large methane releases lead to strong aerosol forcing and reduced cloudiness. Atmos Chem Phys. 2011;11(14):6961–6969. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt GA, Shindell DT. Atmospheric composition, radiative forcing, and climate change as a consequence of a massive methane release from gas hydrates. Paleoceanography. 2003;18(1):4-1–4-9. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagani M, Caldeira K, Archer D, Zachos JC. Atmosphere. An ancient carbon mystery. Science. 2006;314(5805):1556–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1136110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Renssen H, Beets J. Modeling the climate response to a massive methane release from gas hydrates. Paleoceanography. 2004;19(2):PA2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shellito CJ, Sloan LC, Huber M. Climate model sensitivity to atmospheric CO2 levels in the Early-Middle Paleogene. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2003;193(1):113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beerling DJ, Royer DL. Convergent Cenozoic CO2 history. Nat Geosci. 2011;4(7):418–420. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Royer DL, et al. Paleobotanical evidence for near present-day levels of atmospheric CO2 during part of the tertiary. Science. 2001;292(5525):2310–2313. doi: 10.1126/science.292.5525.2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Currano ED, et al. Sharply increased insect herbivory during the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(6):1960–1964. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708646105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Currano ED, Kattler KR, Flynn A. Paleogene insect herbivory as a proxy for pCO2 and ecosystem stress in the Bighorn Basin, Wyoming, USA. Berichte der Geologischen Bundes-Anstalt. 2011;85:61. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Longinelli A. Oxygen isotopes in mammal bone phosphate: A new tool for paleohydrological and paleoclimatological research? Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1984;48(2):385–390. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luz B, Kolodny Y, Horowitz M. Fractionation of oxygen isotopes between mammalian bone phosphate and environmental drinking water. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1984;48(8):1689–1693. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Luz B, Kolodny Y. Oxygen isotope variations in phosphate of biogenic apatites, IV. Mammal teeth and bones. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1985;75(1):29–36. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryant JD, Froelich PN. A model of oxygen isotope fractionation in body water of large mammals. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1995;59(21):4523–4537. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kohn MJ. Predicting animal δ18O: Accounting for diet and physiological adaption. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1996;60(23):4811–4829. [Google Scholar]

- 44.D’Angela D, Longinelli A. Oxygen isotopes in living mammal’s bone phosphate: Further results. Chem Geol. 1990;86(1):75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dansgaard W. Stable isotopes in precipitation. Tellus. 1964;16(4):436–468. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bryant JD, Luz B, Froelich PN. Oxygen isotopic composition of fossil horse tooth phosphate as a record of continental paleoclimate. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1994;107(3-4):303–316. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharp Z. Principles of Stable Isotope Geochemistry. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luz B, Barkan E, Bender ML, Thiemens MH, Boering KA. Triple-isotope composition of atmospheric oxygen as a tracer of biosphere productivity. Nature. 1999;400(6744):547–550. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bao H, Lyons JR, Zhou C. Triple oxygen isotope evidence for elevated CO2 levels after a Neoproterozoic glaciation. Nature. 2008;453(7194):504–506. doi: 10.1038/nature06959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pack A, Gehler A, Süssenberger A. Exploring the usability of isotopically anomalous oxygen in bones and teeth as paleo-CO2-barometer. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2013;102:306–317. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fricke HC. Investigation of early Eocene water-vapor transport and paleoelevation using oxygen isotope data from geographically widespread mammal remains. Geol Soc Am Bull. 2003;115(9):1088–1096. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Secord R, Wing SL, Chew A. Stable isotopes in Early Eocene mammals as indicators of forest canopy structure and resource partitioning. Paleobiology. 2008;34(2):282–300. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Secord R, et al. Evolution of the earliest horses driven by climate change in the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum. Science. 2012;335(6071):959–962. doi: 10.1126/science.1213859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kohn MJ, Cerling TE. Stable isotope compositions of biological apatite. Rev Mineral Geochem. 2002;48(1):455–488. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gehler A, Tütken T, Pack A. Triple oxygen isotope analysis of bioapatite as tracer for diagenetic alteration of bones and teeth. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2011;310(1):84–91. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gingerich PD, Smith T. 2006. Paleocene-Eocene land mammals from three new latest Clarkforkian and earliest Wasatchian wash sites at Polecat Bench in the northern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Contributions from the Museum of Paleontology (Museum of Paleontology, Univ of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), Vol 31, pp 245–303.

- 57.Gingerich PD. 1989. New earliest Wasatchian mammalian fauna from the Eocene of northwestern Wyoming: Composition and diversity in a rarely sampled high floodplain assemblage. University of Michigan Papers on Paleontology (Museum of Paleontology, Univ of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI), Vol 28, pp 1–97.

- 58.Lindars ES, et al. Phosphate δ18O determination of modern rodent teeth by direct laser fluorination: An appraisal of methodology and potential application to palaeoclimate reconstruction. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2001;65(15):2535–2548. [Google Scholar]

- 59.McKinney CR, McCrea JM, Epstein S, Allen HA, Urey HC. Improvements in mass spectrometers for the measurement of small differences in isotope abundance ratios. Rev Sci Instrum. 1950;21(8):724–730. doi: 10.1063/1.1745698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pack A, Herwartz D. The triple oxygen isotope composition of the Earth mantle and understanding Δ17O variations in terrestrial rocks and minerals. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2014;390:138–145. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sharp ZD. A laser-based microanalytical method for the in situ determination of oxygen isotope ratios of silicates and oxides. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1990;54(5):1353–1357. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pack A, Toulouse C, Przybilla R. Determination of oxygen triple isotope ratios of silicates without cryogenic separation of NF3- technique with application to analyses of technical O2 gas and meteorite classification. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21(22):3721–3728. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Asprey LB. The preparation of very pure fluorine gas. J Fluor Chem. 1976;7(1):359–361. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kohn MJ, Schoeninger MJ, Valley JW. Herbivore tooth oxygen isotope compositions: Effects of diet and physiology. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1996;60(20):3889–3896. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fricke HC, O’Neil JR. The correlation between 18O/16O ratios of meteoric water and surface temperature: Its use in investigating terrestrial climate change over geologic time. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1999;170(3):181–196. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rozanski K, Araguás-Araguás L, Gonfiantini R. Isotopic patterns in modern global precipitation. In: Swart PK, Lohmann KC, McKenzie J, Savin S, editors. Climate Change in Continental Isotope Records. Am Geophysical Union; Washington, DC: 1993. pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gourcy LL, Groening M, Aggarwal PK. Stable oxygen and hydrogen isotopes in precipitation. In: Aggarwal PK, Gat JR, Froelich KFO, editors. Isotopes in the Water Cycle: Past, Present and Future of a Developing Science. Springer; Dordrecht¸ The Netherlands: 1997. pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rozanski K, Araguás-Araguás L, Gonfiantini R. Relation between long-term trends of oxygen-18 isotope composition of precipitation and climate. Science. 1992;258(5084):981–985. doi: 10.1126/science.258.5084.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gingerich PD. 2003. Mammalian responses to climate change at the Paleocene-Eocene boundary: Polecat Bench record in the northern Bighorn Basin, Wyoming. Causes and Consequences of Globally Warm Climates in the Early Paleogene, eds Wing SL, Gingerich PD, Schmitz B, Thomas E, Geological Society of America Special Paper (Geological Soc of America, Boulder, CO), Vol 369, pp 463–478.

- 70.Gingerich PD. Environment and evolution through the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21(5):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Berner RA. Modeling atmospheric O2 over Phanerozoic time. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2001;65(5):685–694. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Beerling DJ. Quantitative estimates of changes in marine and terrestrial primary productivity over the past 300 million years. Proc Biol Sci. 1999;266(1431):1821–1827. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Breecker DO, Sharp ZD, McFadden LD. Atmospheric CO2 concentrations during ancient greenhouse climates were similar to those predicted for A.D. 2100. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(2):576–580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902323106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Royer DL. 2003. Estimating latest Cretaceous and Tertiary atmospheric CO2 from stomatal indices. Causes and Consequences of Globally Warm Climates in the Early Paleogene, eds Wing SL, Gingerich PD, Schmitz B, Thomas E, Geological Society of America Special Paper (Geological Soc of America, Boulder, CO), Vol 369, pp 79–93.

- 75.Greenwood DR, Scarr MJ, Christophel DC. Leaf stomatal frequency in the Australian tropical rainforest tree Neolitsea dealbata (Lauraceae) as a proxy measure of atmospheric pCO2. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 2003;196(3):375–393. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Beerling DJ, Fox A, Anderson CW. Quantitative uncertainty analyses of ancient atmospheric CO2 estimates from fossil leaves. Am J Sci. 2009;309(9):775–787. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stott LD. Higher temperatures and lower oceanic pCO2: A climate enigma at the end of the Paleocene epoch. Paleoceanography. 1992;7(4):395–404. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sinha A, Stott LD. New atmospheric pCO2 estimates from paleosols during the late Paleocene/early Eocene global warming interval. Global Planet Change. 1994;9(3):297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fletcher BJ, Brentnall SJ, Anderson CW, Berner RA, Beerling DJ. Atmospheric carbon dioxide linked with Mesozoic and early Cenozoic climate change. Nat Geosci. 2008;1(1):43–48. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Berner R. GEOCARBSULF: A combined model for Phanerozoic atmospheric O2 and CO2. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2006;70(23):5653–5664. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Berner RA. Inclusion of the weathering of volcanic rocks in the GEOCARBSULF model. Am J Sci. 2006;306(5):295–302. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berner RA. Addendum to “Inclusion of the weathering of volcanic rocks in the GEOCARBSULF model” (R. A. Berner, 2006, V. 306, p. 295–302) Am J Sci. 2008;308(1):100–103. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schubert BA, Jahren AH. Reconciliation of marine and terrestrial carbon isotope excursions based on changing atmospheric CO₂ levels. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1653. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Buffet B, Archer D. Global inventory of methane clathrate: Sensitivity to changes in the deep ocean. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 2004;227(3):185–199. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gu G, et al. Abundant Early Palaeogene marine gas hydrates despite warm deep-ocean temperatures. Nat Geosci. 2011;4(12):848–851. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zachos JC, et al. Rapid acidification of the ocean during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. Science. 2005;308(5728):1611–1615. doi: 10.1126/science.1109004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thiemens MH, Jackson T, Zipf E, Erdman PW, van Egmond C. Carbon dioxide and oxygen isotope anomalies in the mesosphere and stratosphere. Science. 1995;339:780–785. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Barkan E, Luz B. High precision measurements of 17O/16O and 18O/16O ratios in H2O. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2005;19(24):3737–3742. doi: 10.1002/rcm.2250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barkan E, Luz B. The relationships among the three stable isotopes of oxygen in air, seawater and marine photosynthesis. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2011;25(16):2367–2369. doi: 10.1002/rcm.5125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaiser J, Abe O. Reply to Nicholson’s comment on “Consistent calculation of aquatic gross production from oxygen triple isotope measurements” by Kaiser (2011) Biogeosciences. 2012;9(8):2921–2933. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Young ED, Yeung LY, Kohl IE. On the Δ17O budget of atmospheric O2. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2014;135:102–125. [Google Scholar]

- 92.Nagy KA, Peterson CC. Scaling of Water Flux Rate in Animals. Univ of California Press; Berkeley, CA: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nagy KA, Girard IA, Brown TK. Energetics of free-ranging mammals, reptiles, and birds. Annu Rev Nutr. 1999;19(1):247–277. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Bao H, Koch PL, Rumble D., III Paleocene-Eocene climatic variation in western North America: Evidence from the δ18O of pedogenic hematite. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1999;111(9):1405–1415. [Google Scholar]