Significance

Pyroptosis is a form of cell death that is critical for eliminating innate immune cells infected with intracellular bacteria. Microbial products such as lipopolysaccharide, which is a component of Gram-negative bacteria, trigger activation of the inflammatory caspases 1, 4, 5, and 11. These proteases cleave the cytoplasmic protein Gasdermin-D into two pieces, p20 and p30. The p30 fragment is cytotoxic when liberated from the p20 fragment. Our work suggests that p30 induces pyroptosis by associating with cell membranes and forming pores that perturb vital electrochemical gradients. The resulting imbalance causes the cell to lyse and release intracellular components that can alert other immune cells to the threat of infection.

Keywords: GsdmD, pyroptosis, caspase-11

Abstract

Gasdermin-D (GsdmD) is a critical mediator of innate immune defense because its cleavage by the inflammatory caspases 1, 4, 5, and 11 yields an N-terminal p30 fragment that induces pyroptosis, a death program important for the elimination of intracellular bacteria. Precisely how GsdmD p30 triggers pyroptosis has not been established. Here we show that human GsdmD p30 forms functional pores within membranes. When liberated from the corresponding C-terminal GsdmD p20 fragment in the presence of liposomes, GsdmD p30 localized to the lipid bilayer, whereas p20 remained in the aqueous environment. Within liposomes, p30 existed as higher-order oligomers and formed ring-like structures that were visualized by negative stain electron microscopy. These structures appeared within minutes of GsdmD cleavage and released Ca2+ from preloaded liposomes. Consistent with GsdmD p30 favoring association with membranes, p30 was only detected in the membrane-containing fraction of immortalized macrophages after caspase-11 activation by lipopolysaccharide. We found that the mouse I105N/human I104N mutation, which has been shown to prevent macrophage pyroptosis, attenuated both cell killing by p30 in a 293T transient overexpression system and membrane permeabilization in vitro, suggesting that the mutants are actually hypomorphs, but must be above certain concentration to exhibit activity. Collectively, our data suggest that GsdmD p30 kills cells by forming pores that compromise the integrity of the cell membrane.

Pyroptosis is an inflammatory form of programmed cell death that occurs in response to microbial products in the cytoplasm or to cellular perturbations caused by diverse stimuli, including crystalline substances, toxins, and extracellular ATP (1, 2). Pyroptosis plays a critical role in the clearance of intracellular bacteria (3), but may also contribute to autoinflammatory and autoimmune disease pathology. Mechanistically, pyroptosis occurs when cytosolic nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), including NLRP1, NLRP3, and NLRC4, or the pyrin domain-containing protein AIM2, nucleate a canonical inflammasome complex that activates the protease caspase-1 (2). Alternatively, intracellular lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Gram-negative bacteria can trigger noncanonical activation of mouse caspase-11 and human caspases 4 and 5 (4–7). Caspases 1, 4, 5, and 11 can each cleave Gasdermin-D (GsdmD) to mediate pyroptotic cell death (8, 9). It is the N-terminal p30 fragment of GsdmD that is cytotoxic to cells, but precisely how it kills cells is unknown.

Here we show that the human GsdmD p30 fragment liberated by active caspase-11 forms ring-like structures within membranes that function as pores. Therefore, we propose p30 kills cells by directly compromising the integrity of cellular membranes. We also show that the GsdmD I105N mutant that was unable to mediate macrophage pyroptosis (9) is hypomorphic at cell killing in a transient overexpression system and at liposome permeabilization in vitro—conditions where p30 concentration favors oligomerization.

Results

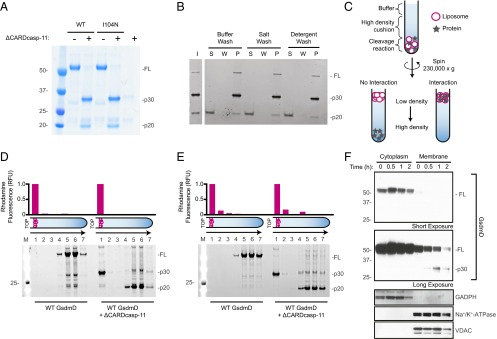

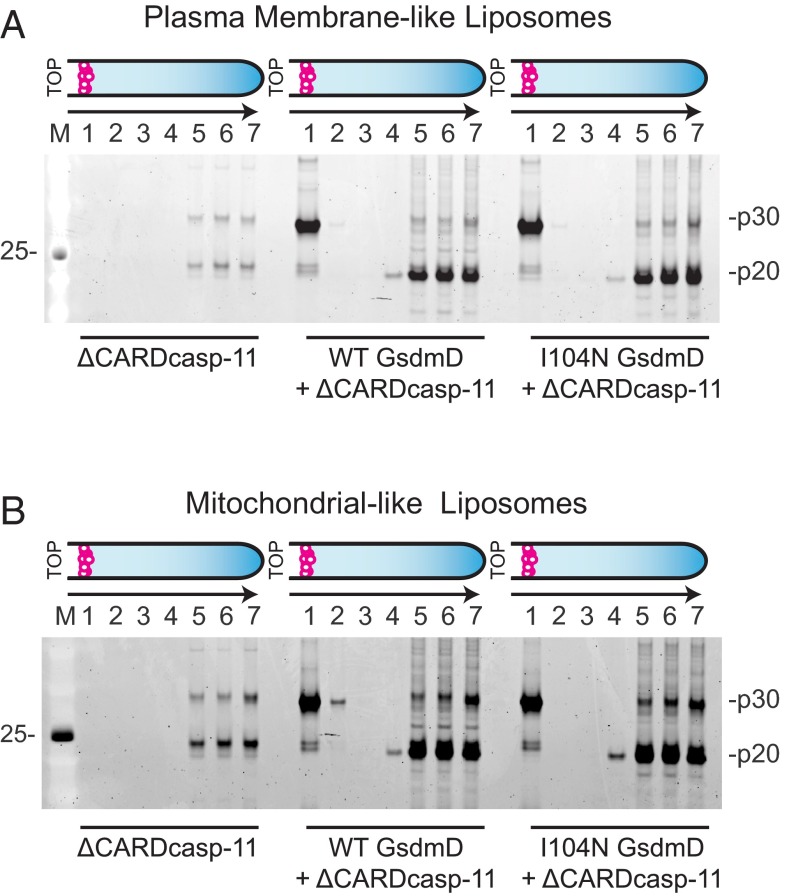

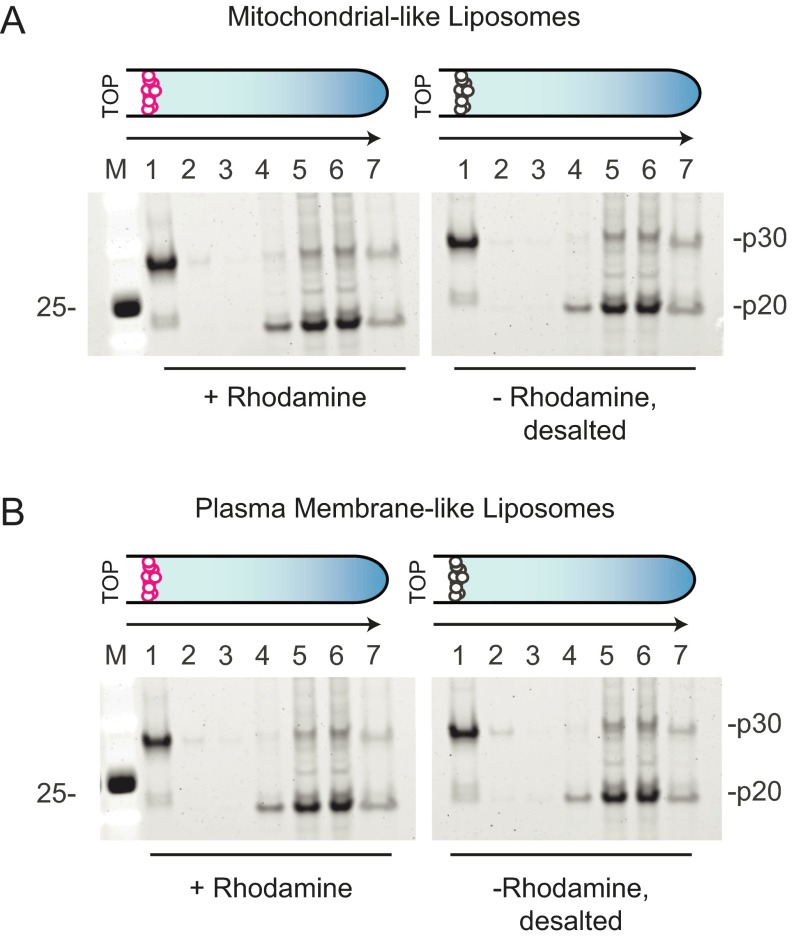

Previous studies demonstrated that both endogenous and recombinantly expressed mouse GsdmD were cleaved by caspase-11 (8, 9). We were also able to cleave recombinant human GsdmD with a constitutively active form of caspase-11 lacking the N-terminal caspase activation and recruitment domain (ΔCARDcasp-11; Fig. 1A). The resulting N-terminal p30 domain precipitated after cleavage, whereas the C-terminal p20 domain was predominantly soluble (Fig. 1B). Given that plasma membrane rupture is a prominent feature of pyroptosis, we hypothesized that the liberated p30 domain favored association with cellular membranes and therefore formed insoluble aggregates in their absence. To test this idea, GsdmD was cleaved by ΔCARDcasp-11 in the presence of liposomes. The resulting reaction was centrifuged over a high-density cushion to float the low-density liposomes and separate them from both the soluble cleavage products and insoluble precipitate (Fig. 1C). GsdmD p30, but not GsdmD p20 or full-length GsdmD, strongly colocalized with liposomes of different lipid compositions (Fig. 1 D and E and Table S1), suggesting that p30 may associate with cellular membranes upon cleavage by caspase-11. Indeed, liposomes composed of either plasma membrane-like or mitochondrial-like lipid bilayers were bound equally well by p30. Interestingly, exclusion of sphingomyelin from the plasma membrane-like liposomes seemed to impair full association of p30 with the membrane (Fig. S1).

Fig. 1.

Processing and membrane partitioning of GsdmD. (A) SDS/PAGE of wild-type (WT) and I104N GsdmD with and without ΔCARDcasp-11 treatment (coomassie staining). Full-length (FL) and cleavage products, p20 and p30, are denoted. (B) WT GsdmD cleavage reactions were subject to sedimentation analysis to assess component solubilities. SDS/PAGE of input (I), supernatant (S), wash (W), and pellet (P) fractions are shown for different washing strategies (see SI Methods, SYPRO ruby staining). (C) Schematic of liposome flotation assay. A high-density medium was used to float the low-density liposomes and any associated proteins. Rhodamine-labeled liposomes are shown as magenta circles, and protein is shown as gray stars. (D and E) Liposome flotation assay fractions were evaluated by SDS/PAGE (SYPRO ruby staining) for reactions containing (D) plasma membrane-like and (E) mitochondrial-like liposomes. Lanes correspond to successive 100-μL layers starting at the top of the assay tube (Left to Right) and solubilized pellet (fraction 7). Liposome quantification of each layer (as measured by rhodamine fluorescence, normalized to the top layer) is depicted in the bar graphs above the gels. (F) Western blots of immortalized macrophages after stimulation with intracellular LPS. Cellular localization markers, GAPDH (glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase), Na+/K+-ATPase (sodium-potassium adenosine triphosphatase), and VDAC (voltage-dependent ion channel), are shown below.

Table S1.

Liposome composition

| Lipid | Lipid composition (%) | ||

| Mitochondrial-like liposomes | Plasma membrane-like liposomes | Plasma membrane-like liposomes (no sphingomyelin) | |

| Phosphatidylcholine (PC) | 45 | 23 | 44 |

| Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) | 30 | 18.5 | 18 |

| Rhodamine-DHPE (Rho-PE)* | 5 | 3 | 3 |

| Phosphatidylinositol (PI) | 10 | 14 | 13 |

| Cardiolipin | 10 | — | — |

| Cholesterol | — | 23 | 22 |

| Sphingomyelin | — | 18.5 | — |

PE substituted for Rho-PE in unlabeled, cargo-loaded liposomes.

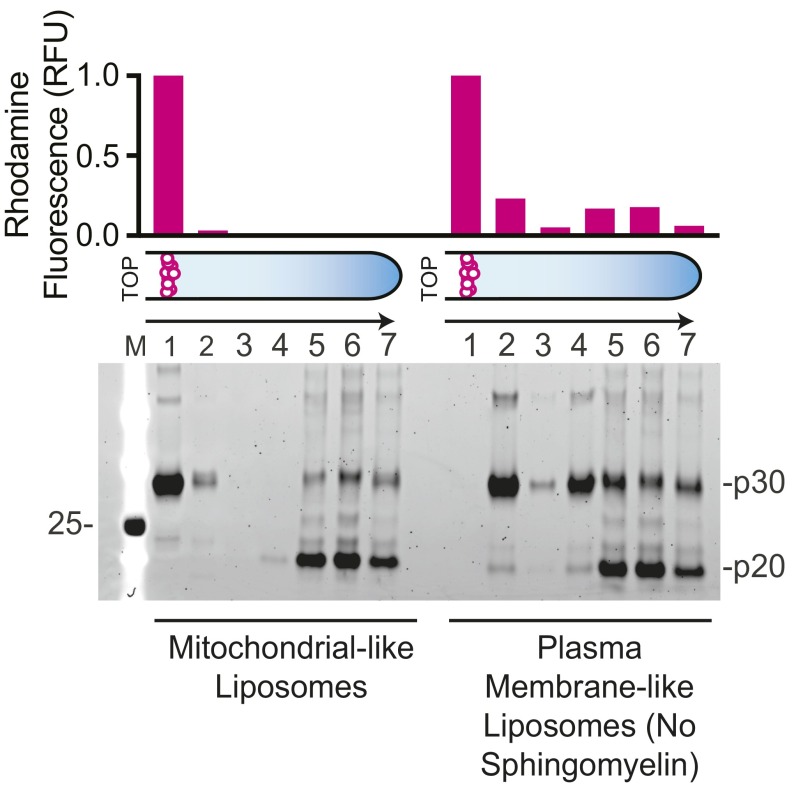

Fig. S1.

Wild-type (WT) GsdmD colocalization with plasma membrane-like liposomes lacking sphingomyelin. Mitochondrial-like and plasma membrane-like liposomes lacking sphingomyelin (Table S1) were incubated with wild-type GsdmD cleavage reactions. Liposomes were then separated using the flotation assay and analyzed by SDS/PAGE (SYPRO ruby staining). The GsdmD cleavage products p20 and p30 are shown. Liposome quantification of each coflotation layer is represented in a bar graph above the gel as rhodamine fluorescence, normalized to the top layer.

Next we determined if endogenous GsdmD p30 localized to membranes in immortalized macrophages after caspase-11 activation by electroporated LPS. Cytosolic and membrane-containing fractions were prepared, with p30 only evident in the latter (Fig. 1F). In contrast, the majority of full-length GsdmD was detected in the cytosolic fraction, and intracellular LPS did not cause it to accumulate in the membrane fraction. The specificity of our GsdmD antibody was confirmed using GsdmD-deficient bone marrow-derived macrophages (Fig. S2). These data support the notion that GsdmD cleavage by caspase-11 promotes translocation of the GsdmD p30 fragment to cell membranes.

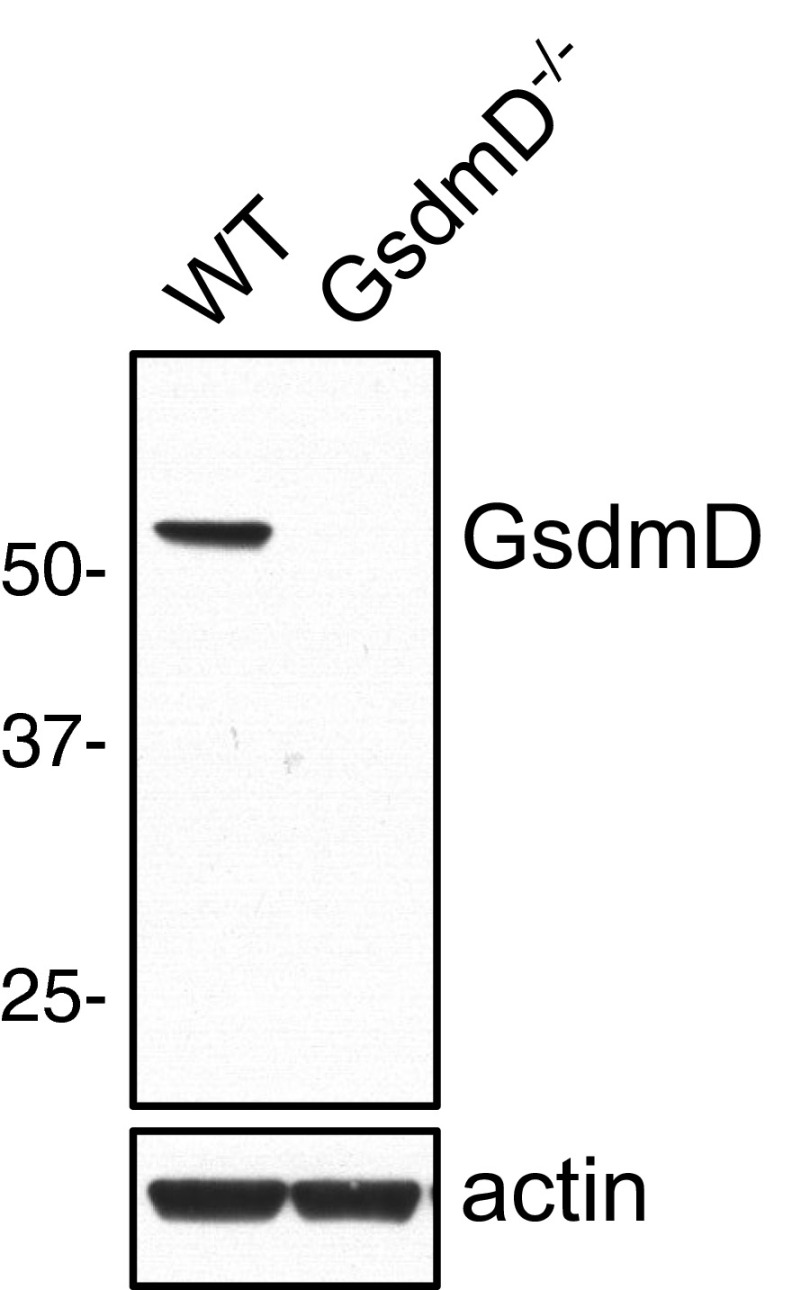

Fig. S2.

Western blots of bone marrow-derived macrophages from indicated mice. Wild-type (WT).

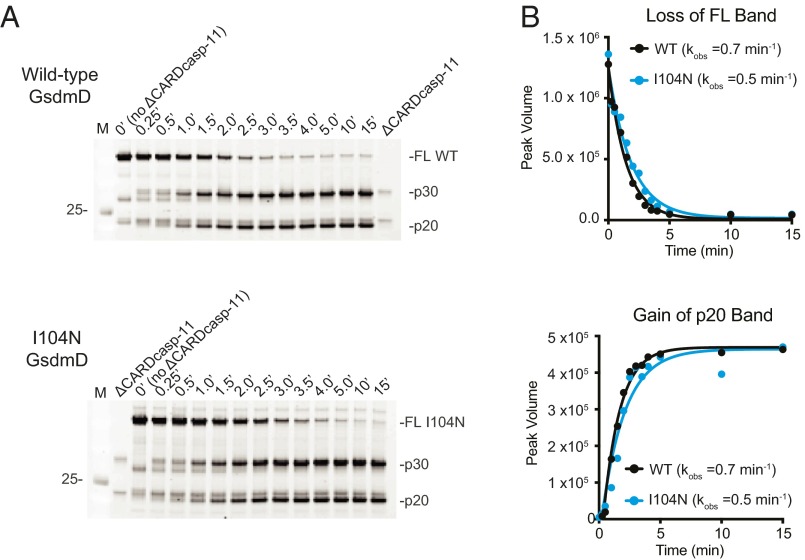

Mutation of isoleucine 105 to asparagine in murine GsdmD was shown to block the cytotoxic activity of GsdmD in mouse macrophages, albeit through an unknown mechanism (9). GsdmD I105N was cleaved by caspase-11 (9); therefore we tested how this mutation affected the membrane association observed for wild-type GsdmD. We confirmed that the corresponding mutation in human GsdmD, I104N, did not impair GsdmD processing by ΔCARDcasp-11 in vitro (Fig. 1A). Indeed, wild-type GsdmD and GsdmD I104N were cleaved with very similar kinetics (Fig. 2 A and B). I104N p30 was also found in the liposome fraction of liposome flotation assays at levels similar to that of wild-type GsdmD, indicating that the mutant is at least competent for membrane association (Fig. 3 A and B).

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of GsdmD cleavage by ΔCARDcasp-11. (A) SDS/PAGE analysis of wild-type (WT) and I104N GsdmD cleavage reaction timecourses (SYPRO ruby staining). (B) Quantification of full-length (FL) and p20 bands for WT (black) and I104N (blue) reactions. Single-exponential fits to the data were used to determine listed rates.

Fig. 3.

GsdmD colocalization with different membrane compositions. Rhodamine-labeled (A) plasma membrane-like and (B) mitochondrial-like liposomes were incubated with wild-type (WT) and I104N cleavage reactions or with ΔCARDcasp-11 alone. Liposomes were separated via flotation assay, and the resulting layers were analyzed by SDS/PAGE (SYPRO ruby staining). GsdmD p20 and p30 cleavage products are denoted.

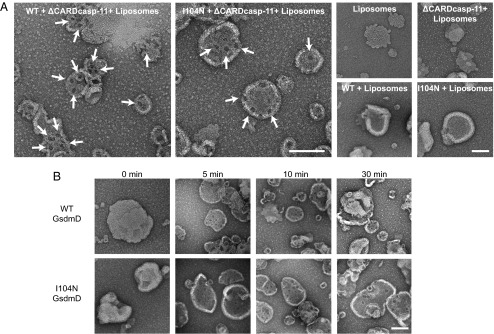

We visualized GsdmD p30 on liposomes directly using electron microscopy. GsdmD cleavage reactions were initiated in the presence of liposomes by addition of ΔCARDcasp-11, and then aliquots were applied onto grids at different time-points and subjected to negative staining. Ring-like structures with darkly stained centers were observed embedded in the liposomes (Fig. 4A). These structures required processing of GsdmD because they were not observed in liposomes exposed to full-length GsdmD or ΔCARDcasp-11 individually. The ring-like structures appeared within 5 min of initiating the cleavage reaction (Fig. 4B). Cleaved GsdmD I104N formed similar structures and on a comparable timescale (Fig. 4B and Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Negative stain electron microscopy images of p30-bound liposomes. (A) Representative images of liposomes incubated with GsdmD cleavage reactions and control samples. Ring-shaped pore structures are highlighted with arrows. (B) Images from a timecourse of GsdmD cleavage reactions initiated by ΔCARDcasp-11. (Scale bar for all images, 100 nm.)

Table 1.

Diameter of ring-like structures visualized by electron microscopy

| Inner pore diameter (nm) | StDev (nm)* | |

| Wild-type GsdmD | 12.8 | 2.4 |

| I104N GsdmD | 13.6 | 2.4 |

n = 50 for both wild-type and I104N.

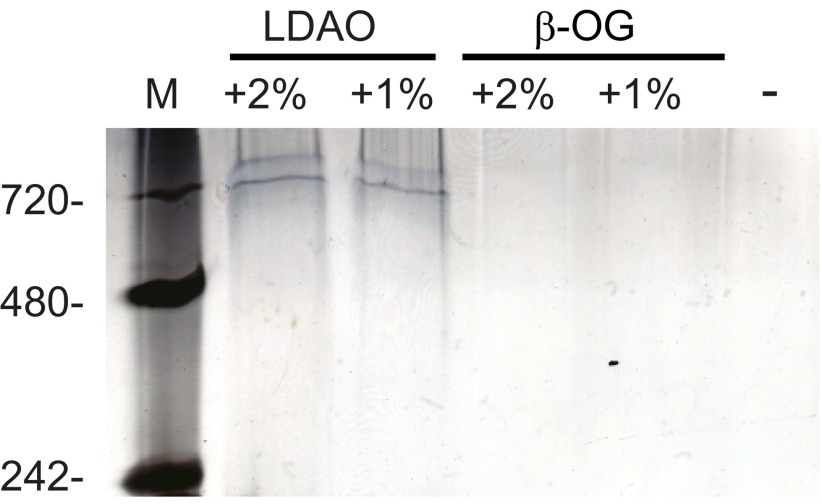

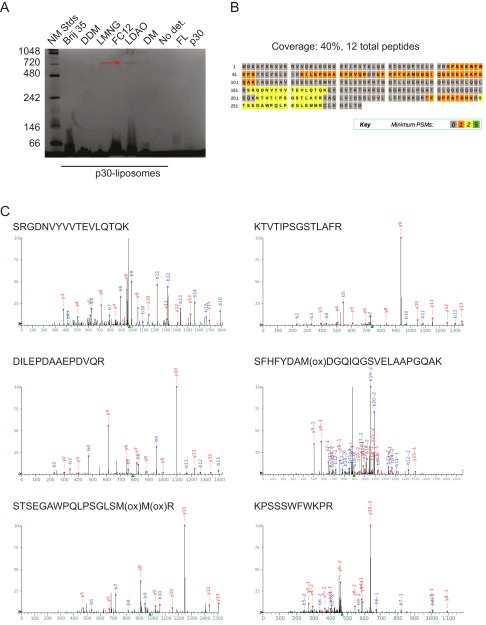

The apparent oligomeric rings were extracted from liposomes using detergent treatment and appeared as a single discrete band at ∼720 kDa on a Blue Native-PAGE gel (Fig. 5 and Fig. S3). Mass spectrometry confirmed that the band contained GsdmD p30 (Fig. S3). Based on its molecular weight, this complex should contain about 24 monomers of p30, which is in keeping with the approximate size and stoichiometry of known pore-forming toxins (10–12). Given that pyroptosis is characterized by formation of pores in the plasma membrane (13, 14), that ectopic GsdmD p30 kills cells (8, 9), and that the C-terminal domain of another gasdermin family member inhibits toxicity of the corresponding N-terminal domain (15), our observations argue that GsdmD p30 that is liberated by caspase-11 forms pores in cellular membranes.

Fig. 5.

Blue Native-PAGE analysis of p30 colocalized to membranes. Liposome-bound p30 was treated with detergent and analyzed by BN-PAGE along with a no-detergent control. Bands were visualized by silver staining. LDAO (n-Dodecyl-N,N-Dimethylamine-N-Oxide) and β-OG (n-Octyl-β-Glucoside).

Fig. S3.

Detergent extraction of GsdmD p30 complex from liposomes. (A) Blue native page gel (coomassie staining) of p30 extraction from liposomes using the panel of detergents listed. The band identified as p30 is indicated by a red arrow. (B) Coverage map of GsdmD p30 sequence. (C) Representative tandem mass spectra confirming the 720-kDa band as GsdmD p30.

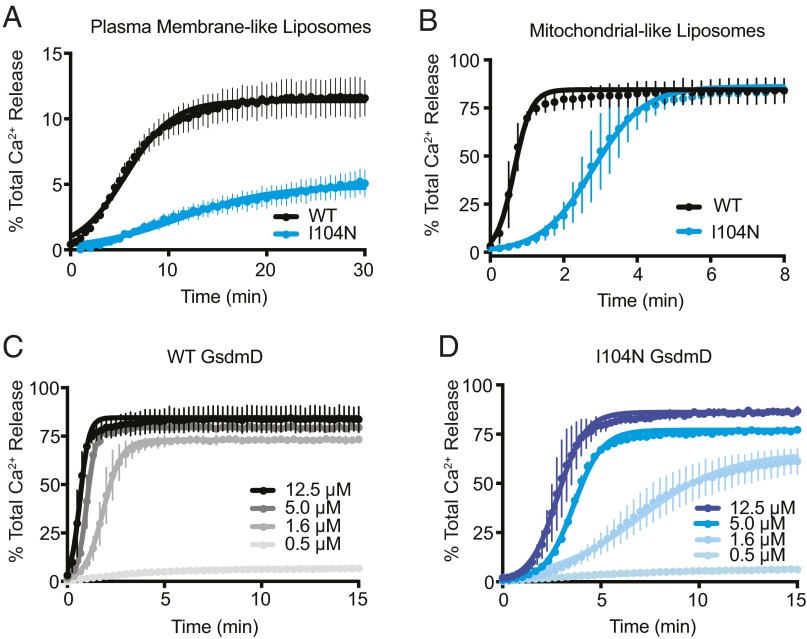

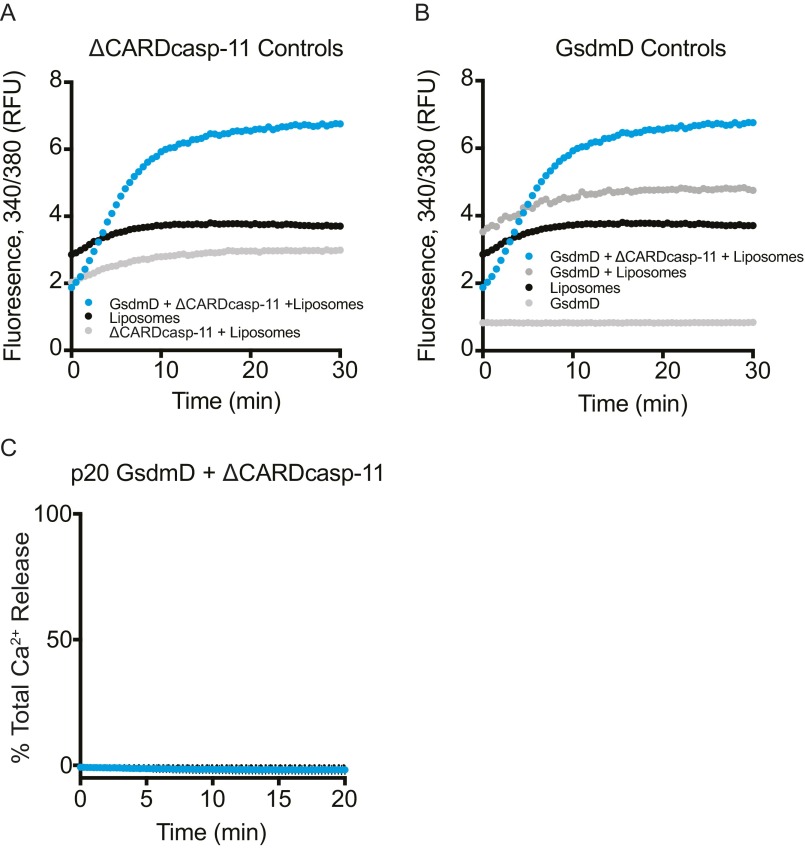

We performed liposome cargo release assays to more directly assess the effect of p30 association on membrane integrity. Liposomes were loaded with calcium chloride, washed via a desalting column, and then added to a ΔCARDcasp-11–mediated GsdmD cleavage reaction. Subsequent release of calcium ions into the surrounding buffer due to membrane permeabilization was monitored using the calcium-sensitive dye Fura-2. Importantly, loading and subsequent desalting of the liposomes had no effect on p30 membrane localization (Fig. S4). Cleavage of full-length GsdmD into p30 and p20 fragments triggered rapid and robust calcium release from liposomes (Fig. 6 A and B). The effect was specific to p30 because no calcium was released by GsdmD p20 with ΔCARDcasp-11, by full-length GsdmD alone, or by ΔCARDcasp-11 alone (Fig. S5). GsdmD p30 effectively permeabilized membranes of different lipid composition, albeit at different rates. The fraction of total signal in the assays also varied with liposome type. GsdmD I104N p30 also caused calcium release from liposomes, but at a significantly slower rate than wild-type GsdmD p30 (Fig. 6 A and B). Dilution of either wild-type or I104N GsdmD retarded the rate of calcium release. However, I104N-mediated membrane permeabilization was more dramatically affected by concentration changes than wild-type (Fig. 6 C and D). Dilution of both GsdmD variants to submicromolar concentration abrogated observable calcium release in the assay.

Fig. S4.

Coflotation assay of desalted liposomes. (A) Mitochondrial-like and (B) plasma membrane-like liposomes were prepared ± rhodamine label. Liposomes without the rhodamine label were desalted via NAP-5 column. All liposomes were then incubated with GsdmD cleavage reactions, separated via flotation assay, and analyzed via SDS/PAGE (SYPRO ruby staining). Successive layers of the coflotation assay, as well as GsdmD cleavage products p20 and p30, are shown.

Fig. 6.

Calcium-loaded liposome release assays. Calcium release from (A) plasma membrane-like and (B) mitochondrial-like liposomes upon incubation with ΔCARDcasp-11 and full-length wild-type (WT) or I104N GsdmD (mean ± SD error bars; n = 6). Dilution series of (C) WT and (D) I104N GsdmD in calcium release assays from loaded mitochondrial-like liposomes (mean ± error bars; n = 3). All fits shown are standard logistic function.

Fig. S5.

Cargo release assay background signal subtraction and controls. (A) ΔCARDcasp-11 background signal. The raw ratio of fluorescence from 340/380 nm excitation is shown for a GsdmD cleavage reaction in the presence of liposomes (blue), as well as the background signal for liposomes alone (black) and liposomes + ΔCARDcasp-11 (gray). Because the ΔCARDcasp-11 storage buffer contains imidazole that binds a fraction of the background calcium signal (compare liposomes alone to liposomes + ΔCARDcasp-11), a parallel ΔCARDcasp-11 + liposomes control assay was used for background subtraction of the data reported in Fig. 6. (B) GsdmD liposome release controls. The raw ratio of fluorescence from 340/380 nm excitation is shown for a GsdmD cleavage reaction in the presence of liposomes (blue), liposomes alone (black), GsdmD + liposomes (dark gray), and GsdmD alone (light gray). (C) GsdmD p20 liposome cargo release assay control. CaCl2-loaded mitochondrial-like liposomes were incubated with ΔCARDcasp-11 and GsdmD p20 and monitored for calcium release (mean ± error bars; n = 3).

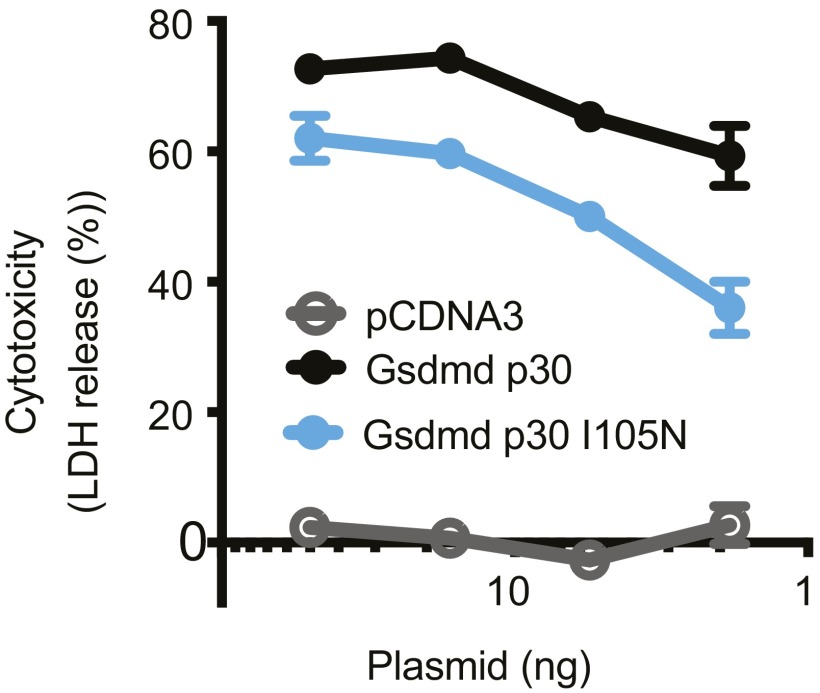

Similar trends were also observed for p30-mediated cytotoxicity in cells. Transient transfection of HEK293T cells with wild-type or I105N mouse p30 caused considerable cell death compared with transfection with vector alone (Fig. 7). However, the toxicity of the I105N mutant was attenuated compared with wild-type p30. Attempts to detect expression of the p30 fragments failed, probably due to how fast they killed the cells.

Fig. 7.

Cytotoxicity of GsdmD p30 variants. Cytotoxicity, as measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, at 24 h after transient transfection of HEK293T cells. Graph shows the mean ± SD of triplicate wells and is representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

Plasma membrane permeabilization is a hallmark of pyroptotic cell death (13, 14). A study of Salmonella-infected macrophages estimated functional pyroptotic pores to be 1.1–2.4 nm in diameter based on the size range of osmoprotectant molecules that prevented cell lysis (13). It was surmised that pores of this size would disrupt ionic gradients and cause water influx, cell swelling, and eventual membrane rupture. Direct imaging of GsdmD p30 pores by negative stain electron microscopy revealed ring-shaped oligomers with an average inner diameter of ∼13 nm (Table 1). Pores of these dimensions might do more than just permeabilize membranes to ions, as shown using liposome cargo release assays (Fig. 6). They would also be theoretically large enough for secretion of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18. These cytokines are cleaved by caspase-1 into their mature, active forms, but they lack sorting motifs for secretion via the classical ER-Golgi secretory pathway. Therefore, it is tempting to speculate that IL-1β and IL-18 could exit the pyroptotic cell through GsdmD p30 pores even before catastrophic membrane rupture by osmotic lysis.

We observed p30 membrane association and permeabilization with both plasma membrane-like and mitochondrial-like liposomes. Whereas p30 membrane localization appeared equivalent for the two lipid compositions in longer timescale liposome flotation assays, p30-mediated calcium release was more rapid and efficient with the mitochondrial-like lipid bilayers. It has been reported that inflammasome activation leads to caspase-1–dependent mitochondrial damage (16). Our findings suggest that formation of GsdmD p30 pores in mitochondrial membranes may account for the observed organelle damage.

Previous work has shown that specific lipids can modulate insertion and/or nucleation of pore-forming toxins (17–20). Our data demonstrate that p30 can bind and permeabilize liposomes of disparate lipid composition, although the rate of calcium release and fraction of total signal in the liposome release assays varied with liposome type (Fig. 6). These data indicate that there is a rate-limiting step between p30 membrane binding and functional pore formation that is affected by lipid composition, presumably either p30 oligomerization or penetration into the lipid bilayer itself. Sphingomyelin is a lipid that gathers into lipid rafts (21, 22), and its exclusion from liposomes appeared to hinder effective p30 association with membranes in coflotation assays. However, sphingomyelin was not required for p30 colocalization with liposomes that contained cardiolipin, another lipid that forms raft-like microdomains (23, 24). Taken together, our data suggest that lipid composition probably influences p30 insertion into the membrane, with lipids that create boundaries or physical distortions in the lipid bilayer facilitating membrane entry.

Irrespective of liposome composition, the I104N mutant p30 colocalized with membranes similar to wild-type p30, but demonstrated slower calcium release from loaded liposomes (Fig. 6). Given that full-length wild-type and I104N GsdmD were cleaved by ΔCARDcasp-11 at similar rates in vitro (Fig. 2), I104N dysfunction appears to be intrinsic to the mutant GsdmD itself rather than affecting interactions with another protein in the signaling cascade. Collectively, our data suggest that the I104N mutation directly impedes p30 pore formation. It is possible that the I104N mutant is defective at membrane insertion, but the permeabilization kinetics would also be consistent with impaired p30 oligomerization.

Our data are consistent with an oligomerization model in which formation of a small, stable “seed” is a rate-limiting step before full assembly into the final ring-like oligomer (25). If the I104N point mutation weakens p30 self-association, this would impair p30 oligomerization by effectively raising the threshold concentration required to form a stable seed. Such a defect could be overcome by increasing the concentration of the mutant. This model may explain why the endogenous I105N mouse mutant blocked noncanonical pyroptosis in macrophages, similar to GsdmD deficient cells (9), but had hypomorphic cell lytic activity when overexpressed in HEK293T cells (Fig. 7). Moreover, nonassembled or improperly assembled mutant p30 fragments would likely contain exposed hydrophobic surfaces and, thus, may be more susceptible to the cell’s quality control mechanisms.

Although the molecular details of p30 assembly and membrane insertion remain to be fully elucidated, our studies indicate a direct role for GsdmD p30 in the formation of pyroptotic pores. Caspase-11 cleavage of GsdmD very effectively removes the inhibitory C-terminal p20 fragment, allowing p30 to assemble into functional pores. The pronounced segregation of p30 and p20 populations, especially in the presence of membranes, suggests that at least one of these newly formed fragments undergoes conformational rearrangements that favor dissociation, as opposed to just a simple covalent decoupling upon proteolytic cleavage. A more detailed understanding of p30-p20 interactions in the autoinhibited full-length protein would enable identification/design of mutations that either impede or enhance GsdmD cytotoxicity. Such mutations would be important tools in probing the molecular mechanisms of p30 inhibition and oligomerization and may also provide important insights into how the cytotoxic p30 domains from the other gasdermin family members (26) are regulated.

Methods

Full-length GsdmD variants were expressed in insect cells and purified to homogeneity. Recombinant ΔCARDcasp-11 was added to process GsdmD into its p30 and p20 fragments. Synthetic liposomes were used to evaluate p30 membrane association and pore formation. Localization of endogenous p30 to cellular membranes was determined by cellular fractionation of LPS-stimulated bone marrow-derived macrophages. Detailed methods are provided in SI Methods.

SI Methods

Protein Purification.

WT and I104N GsdmD were expressed in baculovirus-infected Trichoplusia ni cells as N-terminally His-MBP (Maltose Binding Protein)–tagged fusions and harvested via centrifugation. Frozen cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP) supplemented with 1 mM magnesium chloride, 5 μg/mL DNase I, and Roche complete protease inhibitors (no EDTA), passed through a microfluidizer, and spun for 125,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C to clarify the lysate. The resulting supernatant was incubated with Ni-NTA agarose resin (Qiagen), preequilibrated in lysis buffer, for ∼30 min at 4 °C. Resin slurry was transferred to gravity-flow columns and washed with lysis buffer followed by wash buffer (25 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM, 0.5 mM TCEP). Bound protein was eluted with elution buffer (25 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 300 mM imidazole pH 8.0, 0.5 mM TCEP), and peak fractions were pooled and concentrated using 30 kDa MWCO Ultra-free 15 centrifugal filter devices (Amersham) and dialyzed against wash buffer overnight. The dialyzed pool was cleaved with TEV protease for 1 h at 30 °C followed by passage over a His-trap column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) to remove the His-MBP-tag and uncleaved starting material. Tag-free GsdmD was further purified via size exclusion chromatography using a Sephacryl 300 column [SEC buffer: 20 mM Tris pH7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 4% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.5 mM TCEP], concentrated, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

GsdmD p20 (276-484) was expressed with an N-terminal 6xHis tag and TEV cleavage site in BL21(DE3) cells. Cells were lysed in buffer A1 (50 mM Tris, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP, pH 8.0) and spun to clarify the lysate. Cell supernatant was passed over a Ni-NTA column, washed with buffer A2 (20 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 20 μM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP, pH 8.0), and eluted with buffer B (20 mM Tris, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM TCEP, pH 8.0). Eluted p20 was dialyzed into buffer A2 while cleaving with TEV protease for 12 h at 4 °C. Cleaved p20 was passed through a Ni-NTA column, concentrated, and run over a superdex 75 column in SEC buffer [20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP, 4% (vol/vol) glycerol, pH 7.5].

ΔCARDcasp-11 was expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 cells with a pLYsS plasmid for 4 h at 37 °C. Cells were harvested via centrifugation and frozen at −20 °C. Cell pellets were lysed via sonication and spun at 25,000 × g at 4 °C for 30 min. Supernatant was passed through a 0.45-μm filter, batch-bound to chelating Sepharose fast-flow resin at 4 °C, and washed with 40 mL of wash buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl). Ten milliliters of resuspension buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl) was added to the column, and the protein was eluted using a linear gradient of elution buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 200 mM imidazole). Fractions were kept on ice, tested for caspase-11 activity in cleavage buffer [20 mM Pipes, 10% (wt/vol) sucrose, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS, pH 7.2] using 100 μM LEHD-Afc substrate, and then further analyzed by SDS/PAGE. Active fractions were pooled, flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

Cleavage Reactions.

Concentrated full-length GsdmD and ΔCARDcasp-11 stocks were thawed on ice and individually diluted into cleavage buffer [20 mM Pipes pH7.2, 10% (wt/vol) sucrose, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM ETDA, 10 mM DTT, 0.1% CHAPS]. Reactions were initiated by mixing equivalent volumes of the diluted stocks (final concentrations of 5 μM GsdmD and 1.8 μM ΔCARDcasp-11 unless otherwise specified) and incubating at 37 °C. For determination of cleavage rates, aliquots of the reaction were removed at specific time-points, quenched with SDS sample buffer, and heated at 95 °C for 5 min. Samples were separated by SDS/PAGE and visualized using SYPRO ruby staining and a Typhoon imager. Quantification of band intensities was determined using ImageQuant TL Software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). For cleavage assays that included liposomes, full-length GsdmD was preincubated with liposomes in cleavage buffer for 10 min at room temperature before initiating the reaction with the addition of ΔCARDcasp-11. Final liposome concentration was 1mg/mL unless otherwise specified.

Sedimentation Assay.

GsdmD cleavage reactions (see above) incubated at 37 °C for 30 min were spun at 50,000 RPM in a TLA-55 rotor for 30 min at 4 °C. Supernatant was removed, and the pellets were washed with either buffer (10 mM Hepes pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl), buffer with increased salt concentration (300 mM NaCl), or buffer supplemented with detergent (1% Triton-X100). Centrifugation was repeated, wash supernatant removed, and pellets resuspended in buffer. All samples were separated by SDS/PAGE and visualized by SYPRO ruby staining.

Liposome Formation (Unloaded and Loaded).

Phospholipids were purchased (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.), mixed in chloroform at defined ratios, and dried in a rotary evaporator overnight. The resulting lipid cakes were purged with nitrogen gas and stored at −20 °C until rehydrated in liposome buffer (20 mM Tris Cl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP) at a concentration of 10 mg/mL lipid and resuspended via sonification at room temperature. The liposome mixture was then passed >20 times through an extrusion chamber assembled with a 0.1-μm pore-size filter (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc.) to yield liposome suspensions of homogenous particle size. To load liposomes for the cargo release assays, 50 mM CaCl2 was added to the liposome buffer during the resuspension step. Loaded liposomes were then extruded as above, and unincorporated cargo was removed using a NAP-5 desalting column (GE Healthcare).

Liposome Flotation Assays.

GsdmD association with liposomes was examined by a floating assay because a sedimentation assay could not differentiate insoluble, pelleted protein from protein pelleting due to liposome association. Unless otherwise specified, 5% rhodamine-labeled phosphatidylethanolamine (DHPE, Sigma) was used in the lipid mixture to aid in the detection of liposomes. GsdmD cleavage reactions (see above) incubated at 37 °C for 30 min were added 1:1–80% (wt/vol) Nycodenz/HistoDenz (Sigma-Aldrich) in buffer (20 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5 mM TCEP), and 200 μL of the resulting 40% (wt/vol) Nycodenz/HistoDenz cleavage sample was added to centrifuge tubes. A cushion of 350 μL of 30% (wt/vol) Nycodenz/HistoDenz followed by 70 μL buffer was gently layered on top, and the layered solutions were centrifuged in a SW55Ti rotor (Beckman Coulter) for 3 h at 48,000 RPM. Successive 100-μL layers were pipetted from the top and analyzed by SDS/PAGE with SYPRO ruby staining. Liposome flotation to the top layer was confirmed visually and via detection of the fluorescent rhodamine-PE.

Calcium-Loaded Liposome Release Assays.

Full-length GsdmD, CaCl2 loaded liposomes, and Fura-2 were incubated in caspase cleavage buffer that excluded detergent [20 mM Pipes pH7.2, 10% (wt/vol) sucrose, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM ETDA, 10 mM DTT] for 10 min at room temperature before initiating the reaction by addition of ΔCARDcasp-11 for a final concentration of 12.5 μM GsdmD, 2.5 mg/mL liposomes, 4.5 μM ΔCARDcasp-11, and 10 μM Fura-2. Reactions proceeded at 37 °C, and time-points of dual-wavelength fluorescence were taken using a SpectraMax5E plate reader (Molecular Devices) at 340/380 nm excitation, 510 nm emission. The ratio of emission at 510 nm from 340/380 nm excitations was then calculated to give the raw release signal. Because the ΔCARDcasp-11 stock contained imidazole, which effected the background signal, a side-by-side control of liposomes + ΔCARDcasp-11 was background-subtracted from the GsdmD + ΔCARDcasp-11 + liposomes raw signal (Fig. S5). To account for small differences in liposome concentration due to pipetting error, the data from each sample were converted to a percentage of total calcium release [as measured by addition of 2% (wt/vol) Triton-X100 to the completed reaction] to give the final readout reported in Fig. 6.

Negative Staining and Image Collection.

GsdmD cleavage reactions were initiated at 37 °C with a final liposome concentration of 0.5 mg/mL. At the time-points indicated, 4 μL aliquot of liposome sample was placed onto a continuous carbon grid that had been glow-discharged for 30 s. After 30 s of incubation on the grid at room temperature, the sample was negatively stained with a solution of 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate and blotted dry. Samples were imaged using a Tecnai 12 BioTwin-transmission electron microscope operating at 120 keV at a nominal magnification of 42,000× (2.7 Å/pixel at the detector level) and 110,000× (1.03 Å/pixel at the detector level) using a defocus range of −0.5 to −1.3 μm. Images were recorded on a Gatan 4096 × 4096 pixel CCD camera using the software Digital Micrograph (Gatan, Inc.). Pore diameters were measured using ImageJ software.

Detergent Extraction and Blue Native-PAGE.

GsdmD p30-bound liposomes were purified by liposome flotation assay and flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen. Thawed samples were treated with detergent for 30 min at room temperature. Samples were analyzed by blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE) using the Native-PAGE Bis-Tris system and Native-Mark unstained markers (Novex). Protein bands were visualized with either coomassie staining or silver staining (SilverQuest), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Detergents: 1% Brij-35, 1% DDM (Dodecyl Maltoside), 1% LMNG (Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol), 1% FC12 (n-Dodecylphosphocholine), 1–2% LDAO (n-Dodecyl-N,N-Dimethylamine-N-Oxide), 1–2% β-OG (n-Octyl-β-Glucoside), and 2% DM (Decyl Maltoside). All detergents were supplied by Anatrace, except for Bridj-35, which was supplied by Calbiochem.

Mass Spectrometry.

Band of interest on SDS/PAGE gel was excised and washed in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (Burdick and Jackson) in 50:50 acetonitrile: water (100 µL, 20 min). The gel slice was dehydrated with acetonitrile and digested with trypsin (Promega) in ammonium bicarbonate pH 8.0, 0.2 µg overnight at 37 °C. Peptides were extracted from the gel slice(s) in 50 µL of 50:50 vol/vol acetonitrile: 1% formic acid (Sigma) for 30 min followed by 50 µL of pure acetonitrile. Extractions were pooled and evaporated to near dryness and were reconstituted in 2% acetonitrile: 0.1% formic acid. Samples were injected via an autosampler onto a 75 µm × 100 mm column (ethylene bridged hybrid, 1.7 μm, Waters Corporation) at a flow rate of 1 µL/min using a NanoAcquity ultraperformance liquid chromatography (Waters Corporation). A gradient from 98% solvent A (water + 0.1% formic acid) to 80% solvent B (acetonitrile + 0.08% formic acid) was applied over 40 min. Samples were analyzed online via nanospray ionization into a hybrid linear trap quadropole-Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were collected in data-dependent mode with the parent ion being analyzed in the Fourier transform mass spectrometry and the top eight most abundant ions being selected for fragmentation and analysis in the LTQ. Tandem mass spectrometric data were analyzed using the Mascot search algorithm (Matrix Sciences).

LPS Stimulation and Fractionation.

ER-Hoxb8–immortalized macrophages were maintained and differentiated as described (9). The macrophages were cultured overnight in 24-well plates at 1 × 106 cells/mL before being primed for 5–6 h with 1 μg/mL Pam3CSK4 (Invivogen). Primed cells were electroporated with 5 μg/mL LPS (Invivogen, O111:B4 ultra pure grade) in OPTI-MEM (Life Technologies) using the 4D-Nucleofector system (Lonza) as described (5). Cytosolic and membrane fractions were isolated as described (27). Briefly, cytosolic fractions were extracted in buffer A [20 mM Hepes (pH 7.5), 100 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2,100 mM sucrose, and 1× complete protease inhibitor tablet (Roche)] with 0.025% digitonin. The insoluble crude membrane fraction was then extracted in buffer A with 1% digitonin. For immunoblotting, samples were resolved on a 10% Bis-Tris PAGE gel (Life Technologies) and probed using 1 μg/mL of anti-GsdmD antibody (raised against full-length recombinant mouse GsdmD, mouse IgG2b, clone 17G2G9, Genentech), anti-Na+/K+-ATPase antibody (Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), anti-VDAC antibody (Cell Signaling, 1:1,000), and anti-GAPDH antibody (Abcam, 1:2,500).

Transient Transfection.

Mouse p30 GsdmD (M1-D276) cDNA was artificially synthesized and subcloned into pcDNA3.1/Zeo(+) (Life Technologies) for transient expression in HEK293T cells. The p30 GsdmD I105A mutant was created with a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies). For transient expression, HEK293T cells (ATCC) were cultured overnight in 96-well plates at 1.2 × 105 cells/mL, then transfected with 2–50 ng of plasmids by using 0.16 mL lipofectamine2000 (Life Technologies). At 24 h after transfection, cytotoxicity against HEK293T cells was measured by CellTiter-Glo (Promega).

Acknowledgments

We thank Irma Stowe, Bettina Lee, and Mike Holliday for technical assistance; Joyce Lai for assistance with anti-GsdmD antibody reagents; Kim Newton for editing of the manuscript; and Guy Salvesen for helpful discussions. We also thank the BioMolecular Expression Group for construct generation, expression analysis, and large-scale expression.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: R.A.A., A.E., A.G., P.S.L., N.K., C.C., V.M.D., and E.C.D. were employees of Genentech, Inc.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1607769113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Cookson BT, Brennan MA. Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9(3):113–114. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01936-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lamkanfi M, Dixit VM. Mechanisms and functions of inflammasomes. Cell. 2014;157(5):1013–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miao EA, et al. Caspase-1-induced pyroptosis is an innate immune effector mechanism against intracellular bacteria. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(12):1136–1142. doi: 10.1038/ni.1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kayagaki N, et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479(7371):117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kayagaki N, et al. Noncanonical inflammasome activation by intracellular LPS independent of TLR4. Science. 2013;341(6151):1246–1249. doi: 10.1126/science.1240248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hagar JA, Powell DA, Aachoui Y, Ernst RK, Miao EA. Cytoplasmic LPS activates caspase-11: Implications in TLR4-independent endotoxic shock. Science. 2013;341(6151):1250–1253. doi: 10.1126/science.1240988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi J, et al. Inflammatory caspases are innate immune receptors for intracellular LPS. Nature. 2014;514(7521):187–192. doi: 10.1038/nature13683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi J, et al. Cleavage of GSDMD by inflammatory caspases determines pyroptotic cell death. Nature. 2015;526(7575):660–665. doi: 10.1038/nature15514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kayagaki N, et al. Caspase-11 cleaves gasdermin D for non-canonical inflammasome signalling. Nature. 2015;526(7575):666–671. doi: 10.1038/nature15541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dal Peraro M, van der Goot FG. Pore-forming toxins: Ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2016;14(2):77–92. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tilley SJ, Orlova EV, Gilbert RJ, Andrew PW, Saibil HR. Structural basis of pore formation by the bacterial toxin pneumolysin. Cell. 2005;121(2):247–256. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leung C, et al. Stepwise visualization of membrane pore formation by suilysin, a bacterial cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. eLife. 2014;3:e04247. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fink SL, Cookson BT. Caspase-1-dependent pore formation during pyroptosis leads to osmotic lysis of infected host macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8(11):1812–1825. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bergsbaken T, Fink SL, Cookson BT. Pyroptosis: Host cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7(2):99–109. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin HY, Lin PH, Wu SH, Yang LT. Inducible expression of gasdermin A3 in the epidermis causes epidermal hyperplasia and skin inflammation. Exp Dermatol. 2015;24(11):897–899. doi: 10.1111/exd.12797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu J, et al. Inflammasome activation leads to Caspase-1-dependent mitochondrial damage and block of mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(43):15514–15519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1414859111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giddings KS, Johnson AE, Tweten RK. Redefining cholesterol’s role in the mechanism of the cholesterol-dependent cytolysins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(20):11315–11320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2033520100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimada Y, Maruya M, Iwashita S, Ohno-Iwashita Y. The C-terminal domain of perfringolysin O is an essential cholesterol-binding unit targeting to cholesterol-rich microdomains. Eur J Biochem. 2002;269(24):6195–6203. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waheed AA, et al. Selective binding of perfringolysin O derivative to cholesterol-rich membrane microdomains (rafts) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(9):4926–4931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091090798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abrami L, van Der Goot FG. Plasma membrane microdomains act as concentration platforms to facilitate intoxication by aerolysin. J Cell Biol. 1999;147(1):175–184. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.1.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown DA, Rose JK. Sorting of GPI-anchored proteins to glycolipid-enriched membrane subdomains during transport to the apical cell surface. Cell. 1992;68(3):533–544. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90189-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zech T, et al. Accumulation of raft lipids in T-cell plasma membrane domains engaged in TCR signalling. EMBO J. 2009;28(5):466–476. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renner LD, Weibel DB. Cardiolipin microdomains localize to negatively curved regions of Escherichia coli membranes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(15):6264–6269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015757108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sorice M, et al. Cardiolipin-enriched raft-like microdomains are essential activating platforms for apoptotic signals on mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2009;583(15):2447–2450. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oosawa F, Asakura S. Thermodynamics of the Polymerization of Protein. Academic Press; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tamura M, et al. Members of a novel gene family, Gsdm, are expressed exclusively in the epithelium of the skin and gastrointestinal tract in a highly tissue-specific manner. Genomics. 2007;89(5):618–629. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hildebrand JM, et al. Activation of the pseudokinase MLKL unleashes the four-helix bundle domain to induce membrane localization and necroptotic cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(42):15072–15077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1408987111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]