Significance

Antibodies are generated by B cells of the adaptive immune system to eliminate various pathogens. A somatic gene rearrangement process, termed V(D)J recombination, assembles antibody gene segments to form sequences encoding the antigen-binding regions of antibodies. Each of the multitude of newly generated B cells produces a different antibody with a unique antigen-binding sequence, which collectively form the primary antibody repertoire of an individual. Given the utility of specific antibodies for treating various human diseases, approaches to elucidate primary antibody repertoires are of great importance. Here, we describe a new method for high-coverage analysis of antibody repertoires termed high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing-adapted repertoire sequencing (HTGTS-Rep-seq). We discuss the potential merits of this approach, which is both unbiased and highly sensitive.

Keywords: antibody repertoires, HTGTS-Rep-seq, V(D)J recombination

Abstract

Developing B lymphocytes undergo V(D)J recombination to assemble germ-line V, D, and J gene segments into exons that encode the antigen-binding variable region of Ig heavy (H) and light (L) chains. IgH and IgL chains associate to form the B-cell receptor (BCR), which, upon antigen binding, activates B cells to secrete BCR as an antibody. Each of the huge number of clonally independent B cells expresses a unique set of IgH and IgL variable regions. The ability of V(D)J recombination to generate vast primary B-cell repertoires results from a combinatorial assortment of large numbers of different V, D, and J segments, coupled with diversification of the junctions between them to generate the complementary determining region 3 (CDR3) for antigen contact. Approaches to evaluate in depth the content of primary antibody repertoires and, ultimately, to study how they are further molded by secondary mutation and affinity maturation processes are of great importance to the B-cell development, vaccine, and antibody fields. We now describe an unbiased, sensitive, and readily accessible assay, referred to as high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing-adapted repertoire sequencing (HTGTS-Rep-seq), to quantify antibody repertoires. HTGTS-Rep-seq quantitatively identifies the vast majority of IgH and IgL V(D)J exons, including their unique CDR3 sequences, from progenitor and mature mouse B lineage cells via the use of specific J primers. HTGTS-Rep-seq also accurately quantifies DJH intermediates and V(D)J exons in either productive or nonproductive configurations. HTGTS-Rep-seq should be useful for studies of human samples, including clonal B-cell expansions, and also for following antibody affinity maturation processes.

The B-lymphocyte antigen receptor (BCR) comprises identical Ig heavy (IgH) and Ig light (IgL) chains. Antibodies are the secreted form of the BCR. The V(D)J recombination process assembles germ-line V, D, and J gene segments into exons that encode the antigen-binding variable region exons of the BCR. The RAG 1 and 2 endonuclease (RAG) initiates V(D)J recombination by generating DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) between V, D, and J gene segments and their flanking recombination signal sequences (RSSs) (1). In this process, the V, D, and J coding ends are generated as covalent hairpins that must be opened and that are often further processed, before being joined by classical nonhomologous end joining (2). Processing of V, D, J coding ends can involve generation of deletions or insertions of nucleotides at the junction regions (2), including the frequent de novo addition of nucleotides by the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase component of the V(D)J recombination process (3). Notably the V(D)J junctional region encodes a major antigen contact region of the antibody variable region, known as complementarity determining region 3 (CDR3), and thus these junctional diversification processes make a huge contribution to antibody diversity.

The mouse IgH locus spans 2.7 megabases (Mb). There are 100s of VHs in the several megabase distal portion of the IgH, with the number varying substantially in certain mouse strains (4). The VHs lie ∼100 kb upstream from a 50-kb region containing 13 DHs, which is followed several kilobases downstream by a 2-kb region containing four JHs. The IgH constant region (CH) exons lie downstream of the JHs. After assembly of a VHDJH exon, transcription initiates upstream of the VH and terminates downstream of the CH exons, with V(D)J and CH portions being fused into the ultimate IgH messenger RNA (mRNA) via splicing of the primary transcript. Due to the random junctional diversification mechanisms, only about 1/3 of assembled IgH V(D)J exons are able to generate in-frame splicing events that place the V(D)J and CH exons in the same reading frame to generate productive (in-frame with functional VH) rearrangements that encode an IgH polypeptide, with the remainder being nonproductive (out-of-frame, in-frame with a stop codon, or using a pseudo-VH) (5). IgL chain variable region exons are assembled from just V and J segments but otherwise follow similar basic principles to those of IgH. The mouse Igκ light chain locus spans 3.2 Mb with 100s of Vκs in a 3.1-Mb region separated by 20 kb from five Jκs downstream whereas the Igλ light chain locus is smaller and less complex (6). RNA splicing again joins assembled VJL exons to corresponding CL exons.

During B-cell development, V(D)J recombination is regulated to ensure specific repertoires and prevent undesired rearrangements. IgH V(D)J recombination occurs stage-specifically in progenitor B (pro-B) cells before that of IgL loci, which occur in precursor B (pre-B) cells. IgH V(D)J recombination is ordered, with D-to-JH joining occurring, usually on both alleles, before appendage of a VH to a DJH complex (Fig. S1A) (2). In addition, the VH-to-DJH step of IgH V(D)J recombination is feedback-regulated with a productive rearrangement leading to cessation of V(D)J recombination on the other allele if it is still in the DJH configuration (2). In contrast, initial nonproductive IgH V(D)J rearrangements do not prevent VH-to-DJH rearrangements from occurring on the other allele. Such feedback regulation generally leads to the typical 40/60 ratio of mature B cells, with two IgH V(D)J rearrangements (one productive) versus one IgH V(D)J plus a DJH rearrangement (7). VH-to-DJH rearrangement is also regulated to generate diverse utilization of the 100s of upstream VHs. Although proximal VHs, notably the most proximal VH (VH81X), are somewhat overused in pro-B V(D)J rearrangements, the sequestering of the DHs and JHs in a separate chromosomal domain from that of the VHs (8, 9), coupled with the phenomenon of locus contraction (10, 11), allows even the most distal VHs to be used. Subsequently, the somewhat biased primary VH repertoire in pro-B cells is subjected to cellular selection mechanisms to generate a more normalized primary repertoire in newly generated B cells (12).

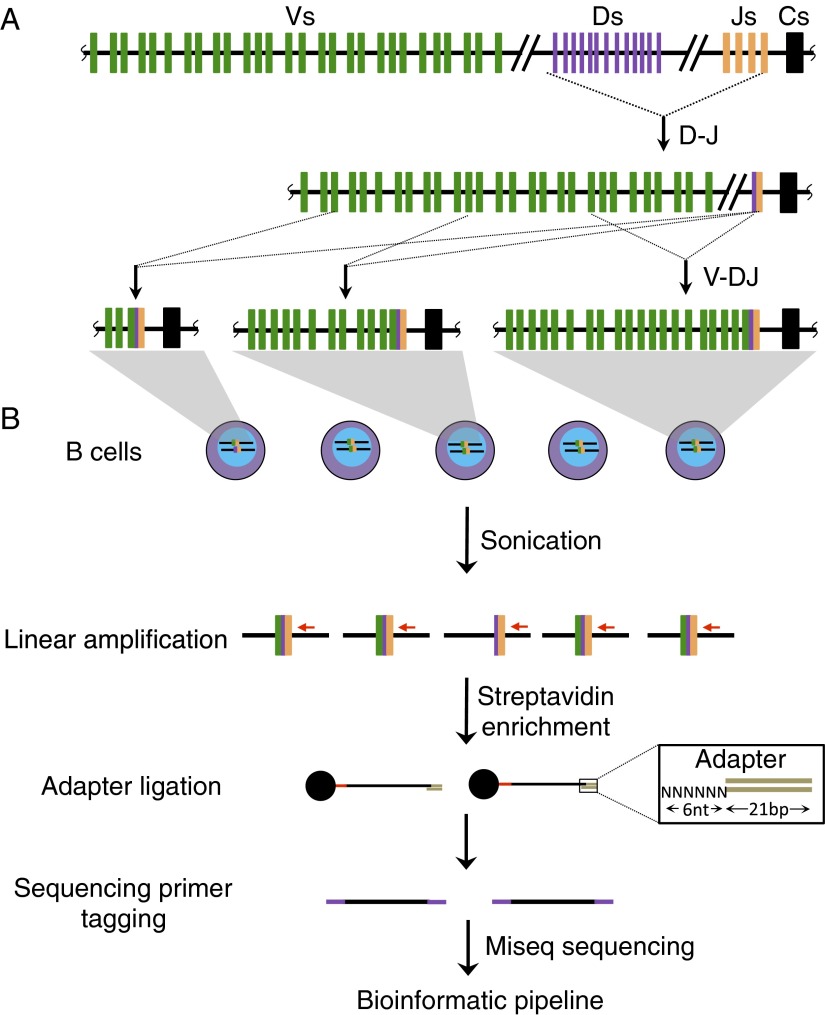

Fig. S1.

Schematic for HTGTS-Rep-seq. (A) Schematic of the generation of DJ and VDJ rearrangements via V(D)J recombination showing Vs (green), Ds (purple), and Js (orange). Representative DJ and VDJ joining events are shown. (B) HTGTS-Rep-seq method overview. Briefly, genomic DNA from B-cell populations are sonicated and linearly amplified with a biotinylated primer that anneals downstream of one specific J segment. The biotin-labeled single-stranded DNA products are enriched with streptavidin beads, and 3′ ends are ligated in an unbiased manner with a bridge adaptor containing a 6-nucleotide random nucleotide (highlighted in the rectangular box). Products were then prepared for 2 × 300-bp sequencing on an Illumina MiSeq. Generated reads were analyzed with the Ig/TCR-Repertoire analysis pipeline described in Materials and Methods.

Each B cell expresses a unique BCR, and each individual mouse or human has the capacity to generate up to 1013 or more distinct BCRs in the primary repertoire (13), with a large fraction of these being generated by junctional diversification of IgH and IgL CDR3s (14). In this regard, the ability to quantitatively identify the IgH and IgL variable region exons that contribute to the primary antibody repertoire is of great interest in elucidating contributions of this repertoire to immune responses and to immune diseases (15). Several important repertoire sequencing assays that use next-generation sequencing have been developed. These approaches involve the generation of repertoire libraries from either genomic DNA or mRNA (15). Most prior DNA-based approaches rely on use of upstream degenerate V primers, each designed to identify members of particular VH families, and a downstream degenerate J primer, an approach that covers many, but not necessarily all, V(D)J exons and likely not all equally. RNA-based approaches generally require only one downstream primer (from the J or constant region) and thus obviate biases in prior DNA-based assays, but these approaches can severely underestimate nonproductive rearrangements due to decreased transcript levels (15). In addition, the long length of the 5′ RACE-derived complementary DNAs can also pose a challenge because sequencing technologies cannot always cover the entire length of the V(D)J exons.

We developed linear amplification-mediated high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing (LAM-HTGTS) to identify unknown “prey” sequences that join to fixed DSB-associated “bait” sequences (16). LAM-HTGTS, like its predecessor HTGTS (17), employs a single primer for a DSB-associated bait sequence to perform linear amplification across bait–prey junctions to identify all prey sequences joined to the bait DSBs in an unbiased manner (16, 18). We have used various types of DSBs as bait for LAM-HTGTS, including those generated by engineered nucleases and endogenous DSBs (17–22). Because V(D)J recombination generates rearrangements with junctions at borders of V, D, and J segments, we can use primers for any of these gene segments as LAM-HTGTS bait to identify sites of RAG-generated DSBs, both in progenitor or precursor lymphocytes undergoing V(D)J recombination, as well as in mature lymphocytes to retrospectively identify V(D)J recombination events that occurred earlier in development. Notably, LAM-HTGTS using endogenous RAG-generated DSBs identified RAG-generated DJH joins, RSS joins in excision circles, and off-target junctions in developing B-lineage cells that were not detected by prior assays (22), illustrating the high sensitivity of the assay. Based on these earlier studies, we now describe an adaptation of LAM-HTGTS as a robust repertoire-sequencing assay that we term “HTGTS-adapted repertoire sequencing” (HTGTS-Rep-seq).

Results

Overview of LAM-HTGTS Adapted Repertoire Sequencing.

For HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries, we used bait coding ends of J segments to identify, in unbiased fashion, mouse IgH DJH repertoires, along with both productive and nonproductive IgH V(D)J repertoires from both pro-B and peripheral B cells. Similarly, we also identified mouse productive and nonproductive Igκ repertoires from peripheral B cells. For all samples analyzed, genomic DNA isolated from a pool of the given type of B cells was sonicated to generate fragments with an average size of ∼1 kb and that thus would be expected to harbor IgH V(D)J or DJ rearrangements, Igκ VJ rearrangements, or unrearranged JHs or Jκs (Fig. S1B). Biotinylated primers that anneal to sequences downstream of the coding end of a particular JH or Jκ segment will allow linear amplification of any fragments containing the bait J segment(s). Subsequent streptavidin purification, adapter ligation, and library construction steps were carried out as previously described (16) (Fig. S1B). To generate longer sequencing reads for more accurate alignment of Vs and Ds, we positioned bait primers closer to the coding ends of bait Js and used MiSeq 2 × 300-bp paired-end sequencing to capture full-length V(D)J sequences in recovered junctions. For bioinformatic analysis, we combined our LAM-HTGTS pipeline with IgBLAST (23) to generate an analysis pipeline that provides comprehensive information on productive or nonproductive junctions and CDR3 sequences (see Materials and Methods for details).

For the HTGTS-Rep-seq, we generally kept for analysis all recovered junctions, including all duplicates for reasons described previously (22). To control for experimental variations, we generated three technical repeat HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from the same splenic B-cell DNA samples, which yielded highly reproducible repertoires with correlation coefficient (r) values of 0.99 (Table S1). Even for biological repeat IgH or IgL HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from pro-B or splenic B cells of three different mice, correlation analyses revealed highly reproducible repertoires with r values greater than 0.9 in most of the datasets (Tables S1 and S2). However, as described below, detailed analyses of certain aspects of such libraries, such as the fraction of unique CDR3s in the total repertoire, revealed expected biological variations (Table S1).

Table S1.

Summary of VDJH joins analysis from HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries of C57BL/6 mice

| Cell type | Locus | Input DNA | Coding end primer | Exp.* | No. of V(D)J junctions, including duplicates | Correlation between % productive V(D)J subsets† | No. of unique CDR3 junctions | Correlation between % productive V(D)J subsets† |

| Pro-B | IgH | 2 μg | JH4 | Mouse 1 | 8,299 | vs. M2: 0.88 | 1,639 | vs. total: 0.97 |

| Mouse 2 | 25,957 | vs. M3: 0.98 | 9,133 | vs. total: 0.99 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 22,613 | vs. M1: 0.85 | 8,894 | vs. total: 0.99 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH4 | Mouse 1 | 45,857 | vs. M2: 0.99 | 20,583 | vs. total: 0.97 |

| Mouse 2 | 57,477 | vs. M3: 0.97 | 38,091 | vs. total: 0.99 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 16,504 | vs. M1: 0.96 | 7,053 | vs. total: 0.97 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH1 | Mouse 1 | 54,172 | vs. M2: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Mouse 2 | 77,670 | vs. M3: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 37,648 | vs. M1: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH2 | Mouse 1 | 66,589 | vs. M2: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Mouse 2 | 81,547 | vs. M3: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 74,857 | vs. M1: 0.99 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH3 | Mouse 1 | 26,586 | vs. M2: 0.99 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Mouse 2 | 29,619 | vs. M3: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 23,097 | vs. M1: 0.99 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH4 | Mouse 1 | 21,532 | vs. M2: 0.97 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Mouse 2 | 26,838 | vs. M3: 0.95 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 12,669 | vs. M1: 0.95 | N.D. | N.D. | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH4 | Repeat 1 | 20,703 | vs. R2: 0.99 | 14,461 | vs. total: 1.00 |

| Repeat 2 | 18,959 | vs. R3: 0.99 | 13,045 | vs. total: 1.00 | ||||

| Repeat 3 | 22,118 | vs. R1: 0.99 | 14,799 | vs. total: 1.00 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 500 ng | JH4 | Repeat 1 | 20,605 | vs. R2: 0.98 | 5,093 | vs. total: 0.99 |

| Repeat 2 | 18,897 | vs. R3: 0.97 | 5,374 | vs. total: 0.99 | ||||

| Repeat 3 | 20,105 | vs. R1: 0.97 | 5,570 | vs. total: 0.99 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 100 ng | JH4 | Repeat 1 | 12,007 | vs. R2: 0.77 | 1,163 | vs. total: 0.96 |

| Repeat 2 | 6,968 | vs. R3: 0.79 | 649 | vs. total: 0.92 | ||||

| Repeat 3 | 8,106 | vs. R1: 0.86 | 896 | vs. total: 0.96 | ||||

| Splenic B | Igκ | 1 μg | Jκ1 | Mouse 1 | 46,554 | vs. C1: 0.99 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Jκ2 | Mouse 1 | 26,117 | vs. C1: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| Jκ4 | Mouse 1 | 16,047 | vs. C1: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| Jκ5 | Mouse 1 | 9,782 | vs. C1: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| Splenic B | Igκ | 1 μg | Jκ1 | Combined | 10,988 | vs. M1: 0.99 | N.D. | N.D. |

| Jκ2 | Combined | 10,159 | vs. M1: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| Jκ4 | Combined | 8,613 | vs. M1: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. | |||

| Jκ5 | Combined | 17,750 | vs. M1: 0.98 | N.D. | N.D. |

N.D., not determined.

Mouse 1, 2, 3, the experiments were performed from three different mice; Repeat 1, 2, 3, the experiments were performed using DNA from the same mouse.

The correlation coefficient values (r) were derived from two sets of productive V(D)J exons (%) via the CORREL function in Excel. The bigger the value, the more similar the two sets of data.

Table S2.

Summary of HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from 129SVE mice

| Cell type | Locus | Input DNA | Coding end primer | Experiment | No. of junctions, including duplicates | Correlation between productive V(D)J subsets |

| Pro-B | IgH | 2 μg | JH4 | Mouse 1 | 20,081 | vs. M2: 0.95 |

| Mouse 2 | 14,950 | vs. M3: 0.93 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 21,701 | vs. M1: 0.96 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH4 | Mouse 1 | 52,140 | vs. M2: 0.98 |

| Mouse 2 | 67,885 | vs. M3: 0.95 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 68,337 | vs. M1: 0.96 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH1 | Mouse 1 | 165,224 | vs. M2: 0.94 |

| Mouse 2 | 102,858 | vs. M3: 0.95 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 97,125 | vs. M1: 0.96 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH2 | Mouse 1 | 191,016 | vs. M2: 0.98 |

| Mouse 2 | 123,362 | vs. M3: 0.96 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 95,336 | vs. M1: 0.96 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH3 | Mouse 1 | 77,966 | vs. M2: 0.97 |

| Mouse 2 | 50,202 | vs. M3: 0.97 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 43,512 | vs. M1: 0.97 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH4 | Mouse 1 | 85,649 | vs. M2: 0.96 |

| Mouse 2 | 37,247 | vs. M3: 0.96 | ||||

| Mouse 3 | 40,422 | vs. M1: 0.97 | ||||

| Splenic B | IgH | 2 μg | JH1 | Combined | 3,652 | N.D. |

| JH2 | Combined | 27,701 | N.D. | |||

| JH3 | Combined | 11,104 | N.D. | |||

| JH4 | Combined | 12,713 | N.D. |

N.D., not determined.

HTGTS-Rep-Seq Reveals IgH VHDJH and DJH Repertoires in Developing and Mature B Cells.

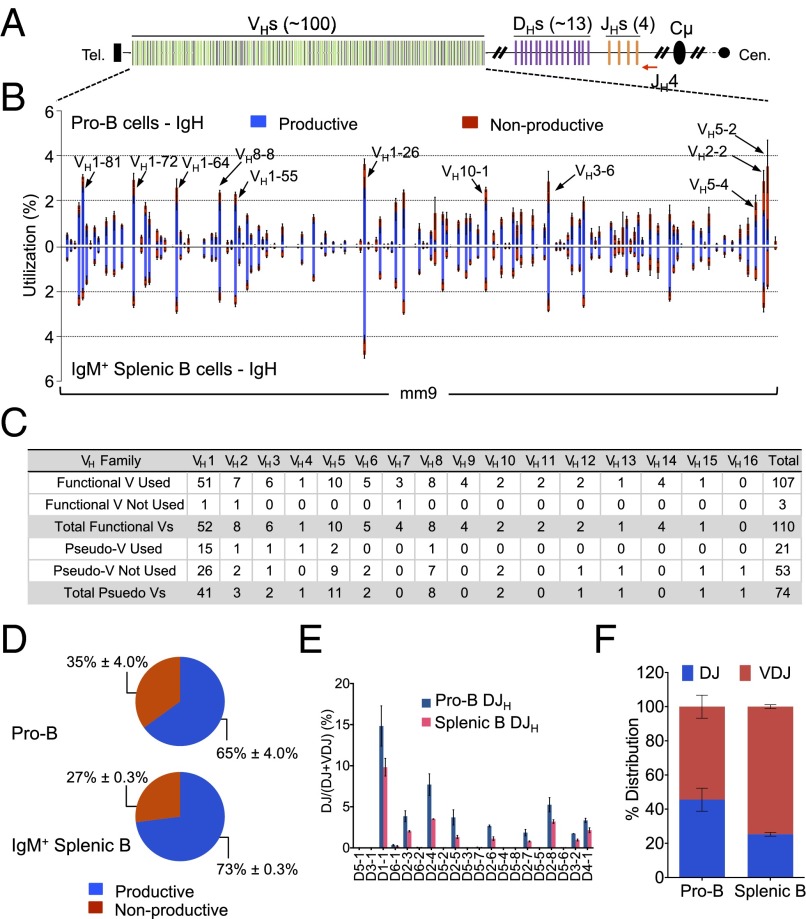

To test the ability of HTGTS-Rep-seq to detect differences between primary pro–B-cell IgH repertoires versus those of peripheral B lymphocytes, we purified primary B220+CD43+IgM− pro-B cells from the bone marrow and B220+IgM+ B cells from the spleen of wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice. We first used 2 μg of genomic DNA isolated from these cell populations to perform HTGTS-Rep-seq with a JH4 coding end bait primer to capture VHDJH4 and DJH4 rearrangements (Fig. 1A and Table S1). Libraries from both cell types showed broad use of VHs in VHDJH4 rearrangements throughout the IgH variable region locus, with some VHs used more frequently (e.g., VH5-2, VH2-2, VH3-6, VH1-26, VH1-64, VH1-72, and VH1-81) (Fig. 1B). The C57BL/6 IgH locus has ∼110 potentially functional VHs and 74 pseudo VHs categorized into 16 families (24). In the IgH repertoire libraries generated with a JH4 coding end bait, we detected in VHDJH exons 107 functional VHs from all 16 families, as well as 21 pseudo VHs with relatively conserved RSSs (Fig. 1C). Notably, the three “functional” VHs (VH1-62-1, VH2-6-8, and VH7-2) not detected by HTGTS-Rep-seq also were not found by another high-throughput repertoire sequencing method (25), suggesting that they may actually be nonfunctional with respect to the ability to undergo V(D)J recombination.

Fig. 1.

HTGTS-Rep-seq of VHDJH and DJH repertoire in pro-B cells and splenic B cells of C57BL/6 mice. (A) Schematic of the murine IgH locus showing VHs (green, functional; black, pseudo), DHs (purple), JHs (orange), and CH region (black). The red arrow indicates the JH4 coding end bait primer. (B) VH repertoire with productive and nonproductive information from VHDJH joins in pro-B cells (Upper) and IgM+ splenic B cells (Lower). Some of the most frequently used VHs are highlighted with arrows as indicated. (C) Utilization numbers of functional VHs and pseudo VHs across 16 families in HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries described in B. (D) Pie chart showing the average overall percentage of productive and nonproductive VHDJH joins from libraries described in B. (E) D use in VHDJH and DJH joins in pro-B cells and IgM+ splenic B cells as indicated. (F) DJH:VHDJH ratios in pro-B cells and IgM+ splenic B cells as indicated. All of the data are showed by mean ± SEM, n = 3.

VH-to-DJH rearrangements occur at the pro-B stage, with only one in three expected to be in-frame (5). In the VHDJH4 exons we identified by HTGTS-Rep-seq, on average 65% were productive, and, correspondingly, 35% were nonproductive (Fig. 1D). This ratio likely reflects a dynamic differentiation process in which pro-B cells with two nonproductive rearrangements are negatively selected and those with a productive rearrangement on one allele are positively selected (12). Due in large part to feedback mechanisms from productive V(D)JH rearrangements during pro–B-cell development, ∼40% of splenic B cells displayed VHDJH rearrangements on both alleles (one productive and one nonproductive) and the remaining 60% had one productive VHDJH and one DJH rearrangement (5). Thus, a population of splenic B cells theoretically would be expected to have about 71% productive VHDJH exons and 29% nonproductive VHDJH exons. Indeed, we observed a very similar ratio of productive/nonproductive VHDJH4 exons (73:27) in the HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from splenic B-cell DNA (Fig. 1D). In the DJH joins revealed by HTGTS-Rep-seq, DH1-1 (also known as DFL16.1) was used most frequently in libraries from both pro-B and splenic mature B cells (Fig. 1E). Moreover, we observed a much higher percentage of DJH exons in pro-B cells compared with that of splenic B cells (45% vs. 25%) (Fig. 1 E and F), in line with D-to-JH rearrangement on both alleles preceding VH-to-DJH rearrangement in developing pro-B cells (5, 26, 27).

Biased Proximal VH Use in 129SVE Mice Revealed by HTGTS-Rep-Seq.

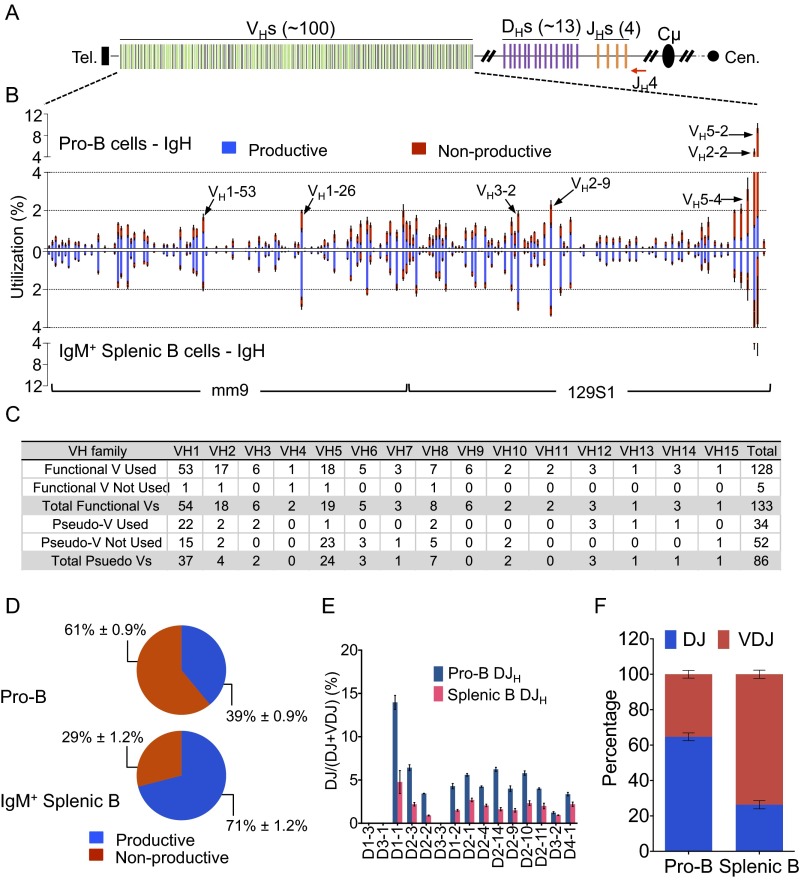

The 129SVE mouse strain IgH locus contains more VHs than the C57BL/6 IgH locus with a somewhat different organization (24). Given that 129SVE mice and cell lines have frequently been used in V(D)J recombination studies, we used the same JH4 bait primers to also generate HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from 129SVE bone marrow pro-B cells and splenic B cells (Table S2). The 129SVE IgH locus VH sequences are annotated up to ∼1 Mb into the variable VH region, but VH sequences lying within the relatively large more distal region of the locus are not completely annotated. Thus, to generate an approximate 129SVE VHDJH repertoire, we ran IgBLAST analyses against a combination of all of the known 129SVE VH sequences and the annotated distal VH sequences from the C57BL/6 background starting from VH8-2 (Fig. S2 A and B). As with the C57BL/6 libraries, the VHs were widely used, and we detected 128 functional VHs out of 133 distinct members of the 15 VH families, plus 34 pseudo VHs (Fig. S2C).

Fig. S2.

HTGTS-Rep-seq of VHDJH and DJH repertoire in pro-B cells and IgM+ splenic B cells of 129SVE mice. (A) Schematic of the murine IgH locus showing VHs (green, functional; black, pseudo), DHs (purple), and JHs (orange). The red arrow indicates the JH4 coding end bait primer. (B) VH repertoire with productive and nonproductive information from VHDJH joins in pro-B cells (Upper) and IgM+ splenic B cells (Lower). Some of the most frequently used VHs are highlighted with arrows as indicated. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. (C) Utilization numbers of functional or pseudo VHs across 16 families in the HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries described in B. (D) Pie charts showing the average overall percentage ± SEM of productive and nonproductive VHDJH joins in pro-B cells (Upper) and IgM+ splenic B cells (Lower). (E) D use in DJH joins in pro-B cells and IgM+ splenic B cells as indicated. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. (F) Comparison of DJH:VHDJH ratios in pro-B cells and IgM+ splenic B cells as indicated. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. Details of the analysis are as described for Fig. 1.

In contrast to the IgH VHDJH4 repertoire in C57BL/6 mice, we found a highly biased use of proximal VHs, especially VH5-2 (also known as VH81X) and VH2-2, in 129SVE mice (Fig. 1B and Fig. S2B). The D-proximal VH5-2 was used in 9.5% (1.7% productive; 7.7% nonproductive) of all VHDJH4 exons in pro-B cells and about 4% (0.3% productive; 3.5% nonproductive) of all VHDJH4 exons in splenic B cells of 129SVE mice (Fig. S2B). In contrast, VH5-2 appeared in only about 3.5% (0.7% productive; 2.8% nonproductive) and about 1.8% (0.15% productive; 1.6% nonproductive) of the VHDJH4 exons in C57BL/6 pro-B and splenic B cells, respectively (Fig. 1B). The majority of VH5-2–containing VHDJH4 joins in splenic B cells were nonproductive in both mouse strains, in contrast to other highly used VHs throughout both alleles (VH2-2, VH5-4, VH3-6, VH1-26, VH1-55, VH8-8, VH1-64, VH1-72, and VH1-81), consistent with previous reports that most VH5-2–containing productive rearrangements are selected against due to their autoreactive properties or inability to properly pair with IgL or surrogate IgL chains (28–30). Because the VH5-2 gene body, associated RSS, and downstream region are conserved in C57BL/6 versus 129SVE mouse strains, the basis for greatly increased VH5-2 utilization in primary repertoires of the 129SVE strain remains to be determined.

A comparison of VHDJH and DJH rearrangements in 129SVE pro–B-cell libraries also revealed a relatively lower ratio of productive/nonproductive VHDJH exons (39:61 in 129SVE vs. 65:35 in C57BL/6), as well as a lower ratio of VHDJH/DJH rearrangements (about 45:55 in 129SVE vs. about 55:45 in C57BL/6) (Fig. 1 D–F and Fig. S2 D–F). VH5-2 rearrangements did not substantially contribute to these differences. Both pro–B-cell libraries were generated in 4-week-old mice, suggesting that the lower relative proportion of productive VHDJH exons in 129SVE compared with C57BL/6 pro-B cells might be attributed to differential timing of B-cell checkpoint selection in these two mouse strains. For both mouse strains, the splenic B-cell libraries showed comparable productive/nonproductive and VDJ/DJ ratios (Figs. 1 D–F and Fig. S2 D–F).

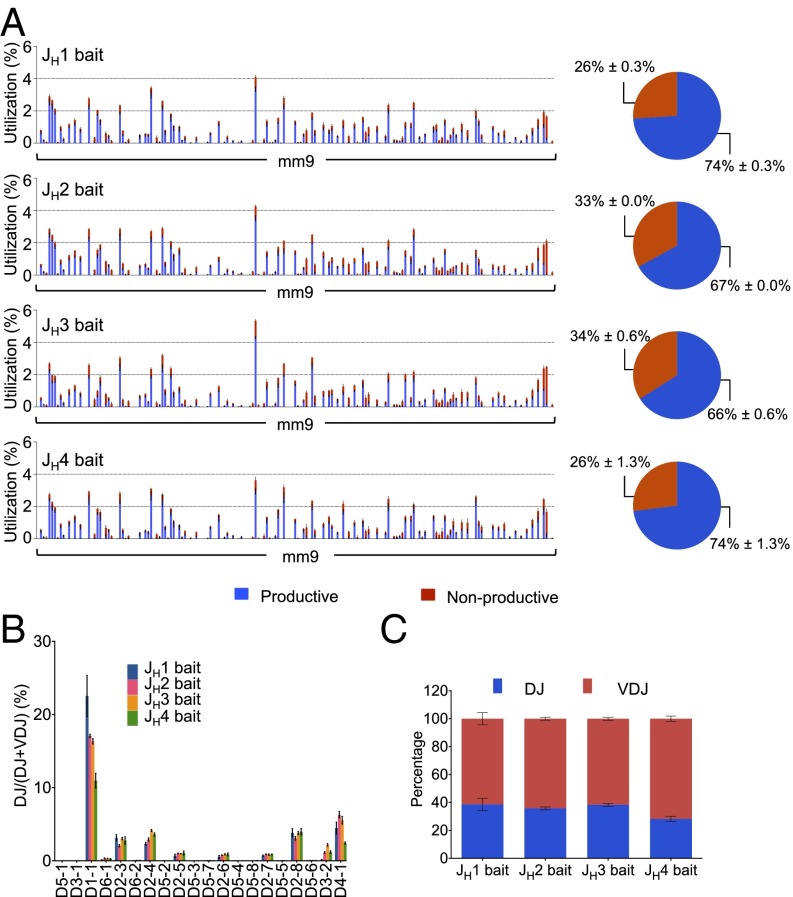

IgM+ Splenic B-Cell VHDJH Exons Display Similar VH Use Profiles Across Different JHs.

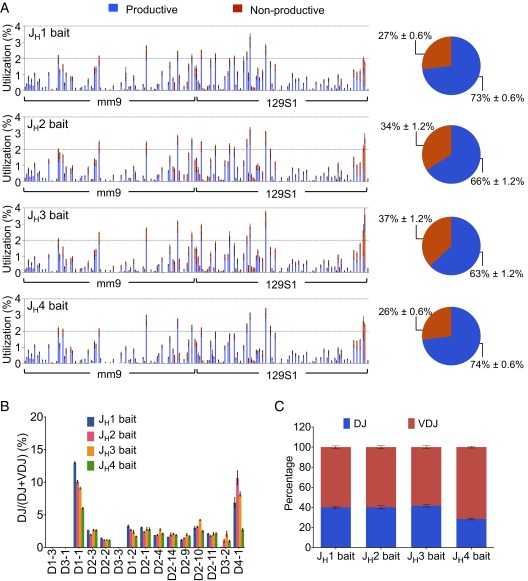

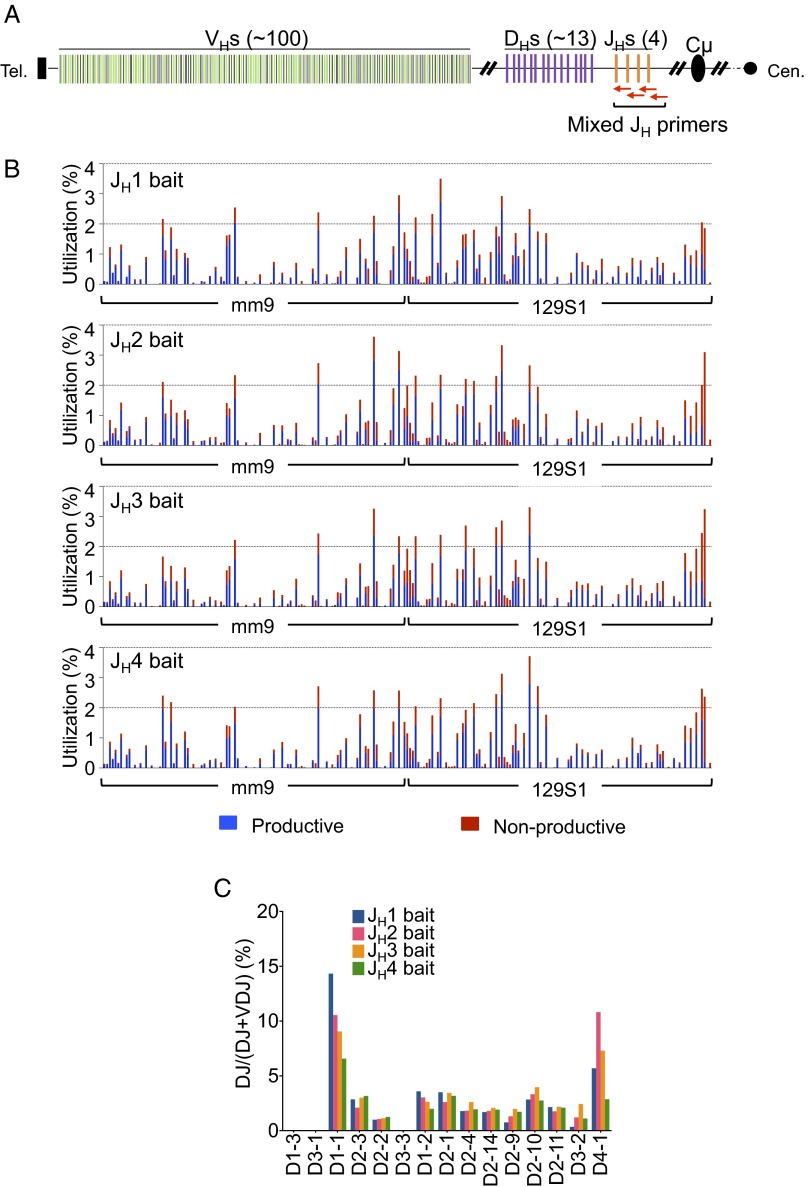

We also designed bait primers to the other three JHs in the IgH locus and made libraries from splenic B cells of both C57BL/6 and 129SVE mice to compare VH and D utilization among the different JHs. These assays revealed similar VH and D utilization repertoires for the four different JHs, indicating that selection for a particular VH or D in a VHDJH join did not vary substantially between the JHs in both C57BL/6 and 129SVE mice (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3A). However, we did find higher proportions of nonproductive VHDJH rearrangements using the JH2 and JH3 baits, compared with the JH1 and JH4 bait libraries (Fig. 2A and Fig. S3A). In this regard, the stretch of sequence from the JH coding ends to the highly conserved WGXG-motif that is crucial for a stable antibody structure (24) is shorter in the JH2 and JH3 segments relative to the JH1 and JH4 segments (Fig. S4A). Thus, some VHDJH2 and VHDJH3 join sites could lie too close to the WGXG-encoded sequences and be selected against due to unstable antibody structure (Fig. S4B). Moreover, we observed moderate differences in the DH use profiles among the four JHs and a larger ratio of VHDJH:DJH joins for the JH4 bait libraries, which potentially could reflect the relative positions of these JHs in the recombination center that initiates V(D)J recombination (31) (Fig. 2 B and C and Fig. S3 B and C). Finally, we prepared HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from 129SVE splenic B cells with four sets of JH HTGTS-Rep-seq primers combined (Fig. S5A and Table S2). This approach, which allowed us to detect all VHDJH1-4 exons in one HTGTS-Rep-seq library, revealed general V(D)J repertoires similar to those detected with individual JH primers (Fig. S5 vs. Fig. S3).

Fig. 2.

VHDJH and DJH repertoires in IgM+ splenic B cells across four JH baits. (A) VH repertoire with productive and nonproductive information from VHDJH joins (Left) and pie charts showing the average overall percentage of productive and nonproductive VHDJH joins (Right) in IgM+ splenic B cells using each of the JH coding end bait primers as indicated. (B) Comparison of D use in DJH joins in IgM+ splenic B cells using each of the JH coding end bait primers. (C) Comparison of DJH:VHDJH ratios in IgM+ splenic B cells using each of the JH coding end bait primers. Mean ± SEM, n = 3 for all of the data. Other analysis details are as described for Fig. 1.

Fig. S3.

Comparison of VHDJH and DJH repertoire in IgM+ splenic B cells of 129SVE mice using four different JH baits. (A) VH repertoire with productive and nonproductive information from VHDJH joins (Left) and pie charts showing the average overall percentage ± SEM of productive and nonproductive VHDJH joins (Right) in IgM+ splenic B cells using individual JH coding end bait primers. (B) Comparison of D use in DJH joins in IgM+ splenic B cells using each of the JH coding end bait primers. (C) Comparison of DJH:VHDJH ratios in IgM+ splenic B cells using each of the JH coding end bait primers. Mean ± SEM, n = 3 for all of the panels. Other analysis details are as described for Fig. 1.

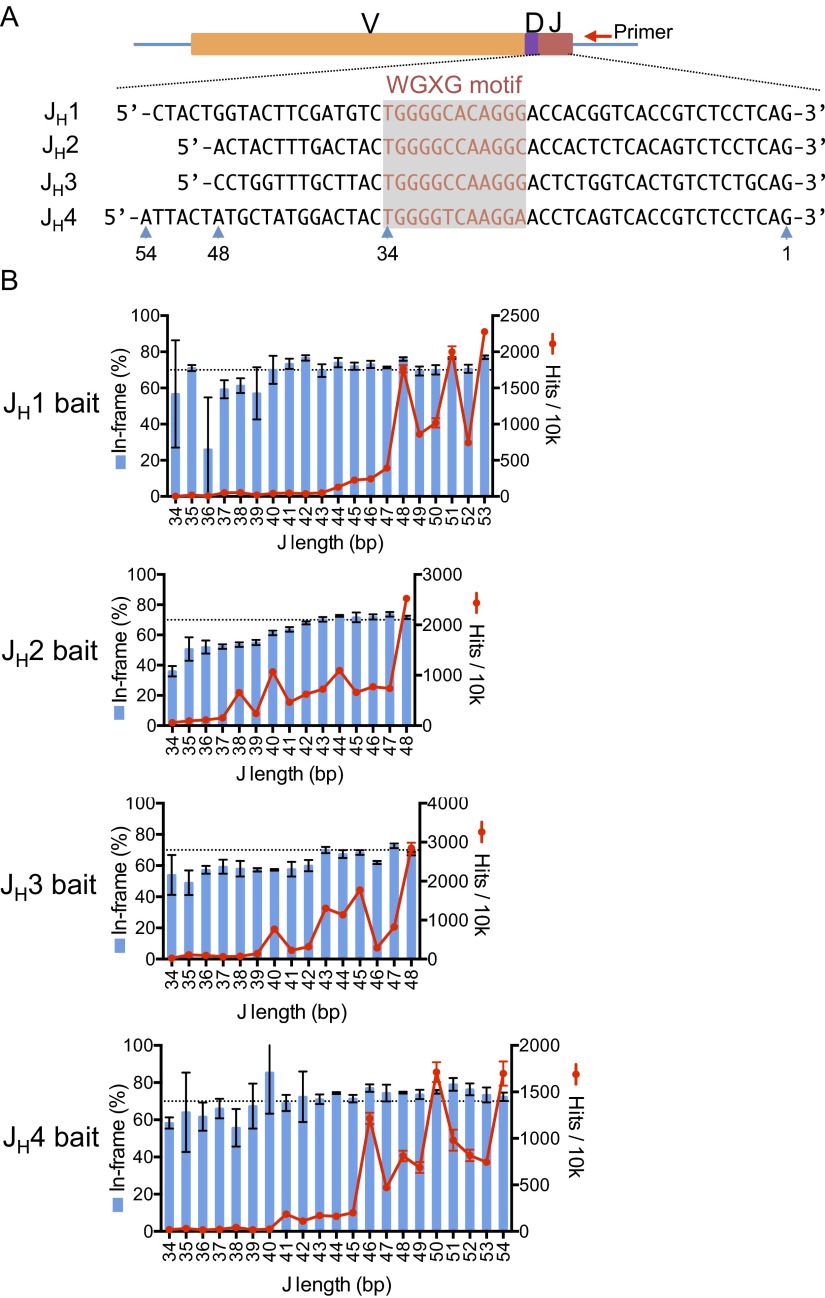

Fig. S4.

In-frame VHDJH proportions across JH coding end lengths for JH1-4. (A) Alignment of the germ-line sequences of JH1-4. The sequences were extracted from the mm9 genome and are highly conserved between 129SVE and C57BL/6. The WGXG-encoding sequences are in red. JH length is marked with blue arrowheads, with 1 indicating the nucleotide most proximal to the bait primer. (B) Red line plots show the number per 10,000 total V(D)J joins that retained the indicated JH length for each JH bait. Blue bar graphs show the percentage of in-frame V(D)J exons at each retained JH length. Mean ± SEM, n = 3.

Fig. S5.

IgM+ splenic B-cell VHDJH use profiles in a 129SVE mouse using four JH baits combined. (A) Schematic of IgH locus as in Fig. 1. Red arrows indicate mixed primers that bind downstream of each JH. (B) VH use profiles separated by JH segment baits. One representative profile is shown here from two repeats of combined primer HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries. (C) D use in DJH joins in IgM+ splenic B cells using each of the JH coding end bait primers.

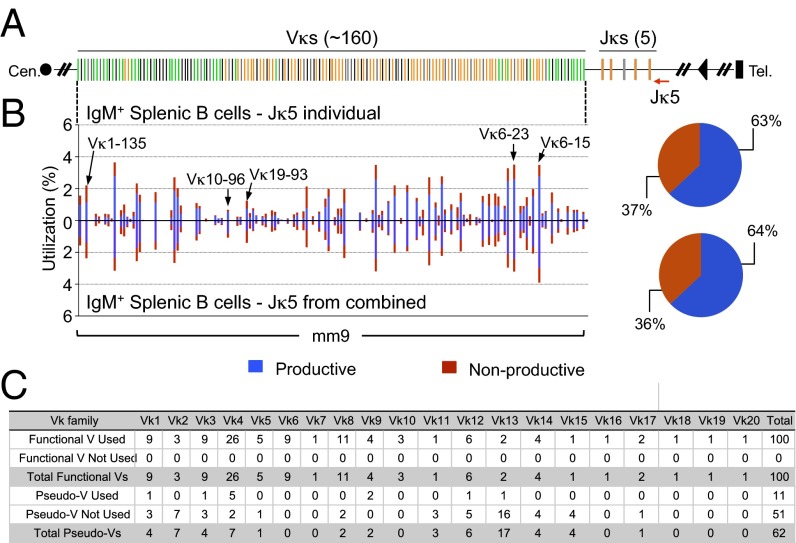

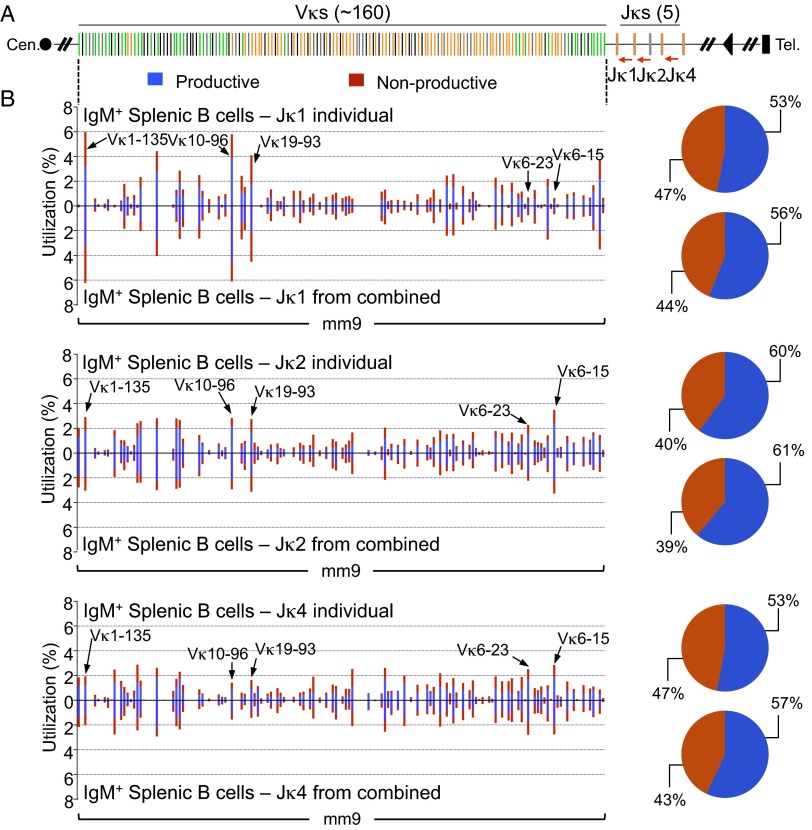

HTGTS-Rep-Seq Detects Diverse Igκ VJ Rearrangements.

In mice, the Igκ locus generates the majority of IgL-expressing B cells (32). The Vκ locus organization is distinct from that of the VH locus. Besides not having D segments and, therefore, undergoing direct Vκ-to-Jκ rearrangements, the Vκ locus contains V segments organized in both direct and inverted orientation relative to the Jκ segments (6) (Fig. 3A). Thus, for some Vκs, joining to Jκ occurs deletionally like VH-to-DJH joining, but, for others, it occurs via inversion of the intervening sequence. Direct and inverted Vκs generally occur in distinct clusters but also can be individually interspersed (Fig. 3A). To first assess the Igκ repertoire, we performed HTGTS-Rep-seq on 1 μg of genomic DNA from C57BL/6 splenic B cells using a Jκ5 coding end bait primer. Similar to the IgH locus, we also observed widespread use of Vκs across the entire locus to the Jκs (Fig. 3 A and B). All of the 100 functional Vκs across 20 Vκ families were detected by HTGTS-Rep-seq, and 11 out of 62 pseudo Vκs were also detected (Fig. 3C). We saw productive/nonproductive VJκ joins at a 63:37 ratio in splenic B cells (Fig. 3B), which is slightly lower than the predicted 67:33 ratio (33). This small deviation might reflect the presence of nonproductive VJκ joins in Igλ-positive cells (32).

Fig. 3.

HTGTS-Rep-seq of VJκ repertoire in IgM+ splenic B cells of C57BL/6 mice using Jκ5 bait primer. (A) Schematic of the murine Igκ locus showing Vκs and Jκs. Green and orange bars indicate functional Vκs with convergent and tandem transcriptional orientations, respectively, to the downstream Jκs. Black bars indicate pseudo Vκs. The red arrow indicates the Jκ5 coding end bait primer. (B, Left) Vκ repertoire with productive and nonproductive information from VJκ joins in IgM+ splenic B cells with Jκ5 bait primer either individually (Upper) or from combined Jκ bait primers (Lower). Some differentially used Vκs among four different Jκs are highlighted with arrows as indicated (see also Fig. S6). (Right) Pie chart showing the overall percentage of productive and nonproductive VJκ joins. Representative results from two repeats are shown. (C) Utilization numbers of functional and pseudo Vκs across 20 families in libraries described in B.

We also generated HTGTS-Rep-seq libraries from splenic B-cell DNAs to capture VJκ joins from the three other functional Jκ segments separately or in a combination of all four Jκ primers. In contrast to IgH repertoires with different JH primers, the Igκ repertoires showed apparently different utilization of some Vκs (e.g., Vκ6-15, Vκ6-23, Vκ19-93, Vκ10-96, and Vκ1-135) between different Jκ baits. Moreover, the productive/nonproductive ratios from the other Jκ primer libraries were slightly lower than those observed with the Jκ5 primer (Jκ1, 53:47; Jκ2, 60:40; Jκ4, 53:47; vs. Jκ5, 63:37) (Fig. S6). These differences in utilization and ratios likely reflect the occurrence of sequential VJκ recombination events (34). In this context, alleles containing nonproductive VJκ joins with the three Jκs upstream of Jκ5 have the ability for an unrearranged Vκ upstream of the nonproductive VJκ to join to a remaining Jκ (34). If this secondary rearrangement is inversional, the nonproductive VJκ joins would be retained in the genome and add to the nonproductive fraction of VJκ1, VJκ2, or VJκ4 joins that are detected by HTGTS-Rep-seq. Given this scenario, VJκ5 rearrangements, which are terminal rearrangement events, would be expected to reflect the theoretical productive/nonproductive ratios, as we have found.

Fig. S6.

Igκ repertoire in IgM+ splenic B cells of C57BL/6 mice using different Jκ baits. (A) Schematic of Igκ locus, as in Fig. 3. Red arrows indicate the position of used Jκ bait primers. (B) Vκ use profiles and overall productive/nonproductive ratios of VJκ separated by Jκ baits in IgM+ splenic B cells. In each panel, representative Vκ repertoires with productive and nonproductive information from VJκ joins with each Jκ bait primer either individually (Upper) or from combined Jκ primers (Lower) are shown. Some differentially used Vκs among four different Jκs are highlighted with arrows as indicated (see also Fig. 3). Representative results from two repeats are shown.

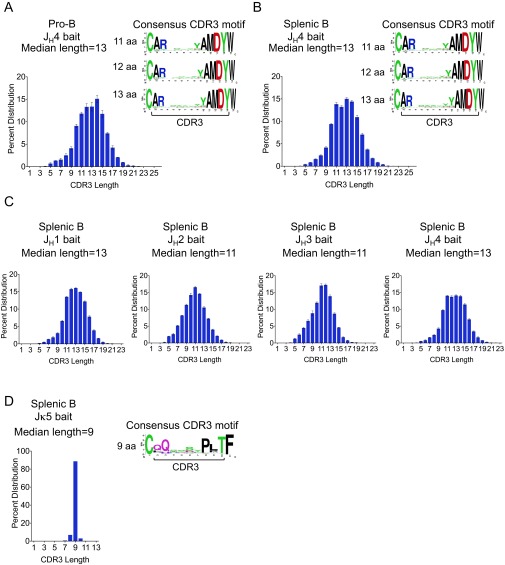

HTGTS-Rep-Seq Revealed Characteristic CDR3 Properties.

We analyzed the CDR3 sequences from productive VHDJH and VJκ rearrangements in pro-B and splenic B cells. The CDR3 of productive VHDJH exons in pro-B and splenic B cells showed a diverse range of lengths from 3 to 24 amino acids (aa) with a peak at 11–15 aa (Fig. S7 A and B). The consensus CDR3 motifs of these VHDJH exons, made from the unique subset, from unimmunized pro-B and splenic B cells, shared the same VH contributed and JH4 contributed amino acid sequences as anticipated (Fig. S7 A and B). Given that the gene bodies of JH2 and JH3 are shorter than those of JH1 and JH4, the average lengths of VHDJH2 and VHDJH3 exons were shorter than those of VHDJH1 and VHDJH4 (median length 11 aa vs. 13 aa) (Fig. S7C). In contrast to productive VHDJH exons, ∼85% of productive VJκ exons from splenic B cells showed a CDR3 length of 9 aa. The VJκ CDR3 motif also showed the expected flanking cysteine and phenylalanine (Fig. S7D). Thus, HTGTS-Rep-seq produces sequences with CDR3 characteristics expected from the various bait loci.

Fig. S7.

CDR3 length distribution and consensus motif of productive VHDJH and VJκ exons. (A) CDR3 length distribution of productive VHDJH exons in C57BL/6 pro-B libraries made with JH4 bait primer. Consensus CDR3 motif plots were made for the subset of 11- to 13-aa-length CDR3 sequences, flanked on either end by the consensus cysteine and tryptophan. (B) As in A, for C57BL/6 splenic B libraries made with JH4 bait primer. (C) As in A, for C57BL/6 splenic B libraries made with the four JH bait primers. Mean ± SEM, n = 3 for A–C. (D) As in A, for C57BL/6 splenic B libraries made with Jκ5 primer. Note that we noticed some errors in our CDR3 sequence analyses due to the basal levels of sequencing errors of current high-throughput sequencing methods, including Illumina MiSeq, and the read length (maximum 600 bp) that are not sufficient to cover entire sequences of longer DNA fragments containing V(D)J exons. However, we eliminated such potential ambiguities by including in our analyses only overlapping joined reads and/or by increasing thresholds for read quality.

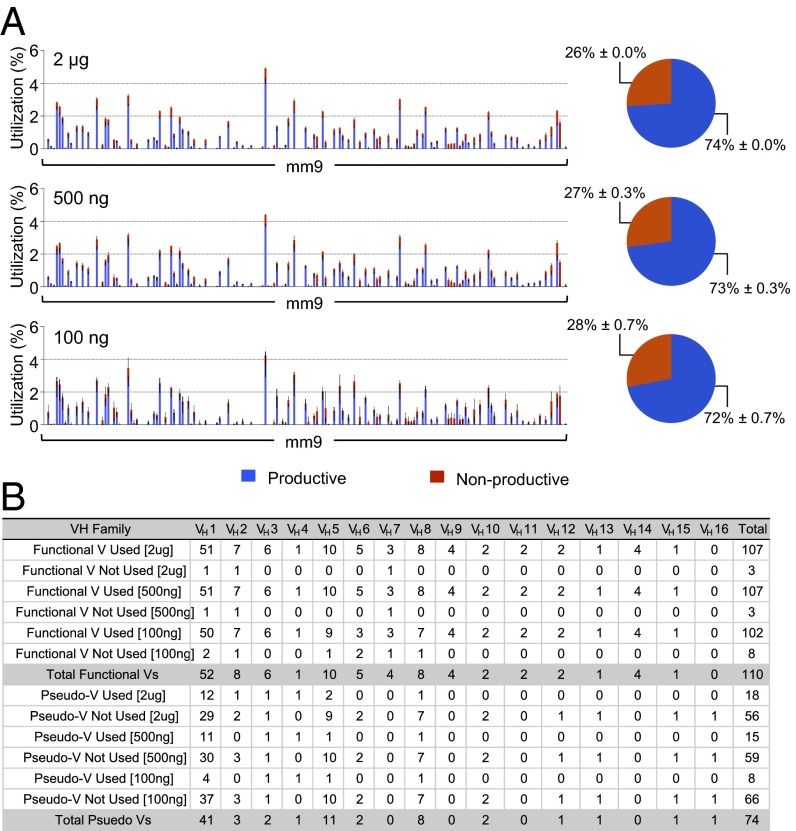

HTGTS-Rep-Seq Can Be Used with Low Amounts of Starting Material.

We generated libraries from JH4 coding end baits with starting DNA amounts of 2 μg, 500 ng, and 100 ng, each purified from the splenic B cells of the same C57BL/6 mouse. Libraries generated from 2 μg and 500 ng of genomic DNA were almost identical (r > 0.97) in VH use and productive/nonproductive rearrangement ratios (Fig. 4 and Table S1). Even though we saw a slight decrease in the number of detected VHs from the libraries generated from 100 ng of genomic DNA, they still displayed a similar repertoire profile (r ≈ 0.8) and productive/nonproductive ratio (Fig. 4), suggesting that HTGTS-Rep-seq can be used to generate a quite representative VHDJH repertoire library from as little as 20,000 B cells.

Fig. 4.

Representative VHDJH repertoire can be generated from small amounts of starting genomic DNA. (A) VH repertoire with productive and nonproductive information from VHDJH joins (Left) and pie charts showing the average overall percentage of productive and nonproductive VHDJH joins (Right) in IgM+ splenic B cells cloned from indicated amounts of genomic DNA using JH4 coding end bait primer. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. (B) VH utilization numbers separated by family, organized as in Fig.1C.

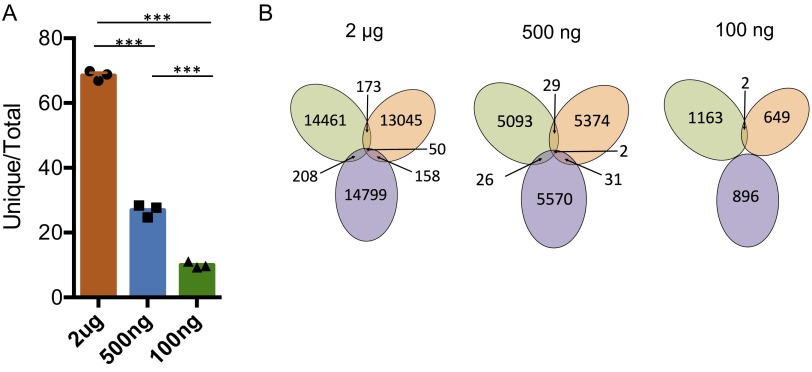

We further evaluated V(D)JH junctional diversities in these titrated libraries by comparing the percentages of unique CDR3 sequences (35). We found that the proportion of V(D)J exons containing unique CDR3 sequences substantially decreased with reduced amounts of starting material (Fig. S8A), indicating that higher amounts of DNA starting material allow us to detect a greater fraction of the highly diverse IgH CDR3 repertoire. Although sequencing errors might in theory lead to minor overestimation of CDR3 diversity, the biological diversity of CDR3 in these samples was so high that we observed only a very small overlap portion in detected V(D)JH CDR3 sequences (<1%) between the three technical repeats of 2-μg DNA libraries and even less between 500-ng or 100-ng DNA library repeat subsets (Fig. S8B). Thus, 100 ng of DNA is enough to generate a representative V(D)JH library with respect to VH use, but even 2 μg of DNA reveals only a very small fraction of the immense diversity of IgH CDR3s.

Fig. S8.

Characterization of unique CDR3 reads. (A) Proportion of unique CDR3 sequences for each technical repeat library from Fig. 4. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. (B) The number of identical CDR3 sequences between technical repeat libraries at varying amounts of starting material.

Discussion

HTGTS-Rep-seq is a DNA-based method that requires only a single bait PCR primer, reads out both deletional and inversional V(D)J joins, and can readily be adapted to identify low frequency recombination events invisible to prior repertoire sequencing assays (22). In addition, HTGTS-Rep-seq can be used to comprehensively study productive and nonproductive V exon use. We also can use HTGTS-Rep-seq to developmentally assess the frequency of V(D)J intermediates, most notably by quantitatively identifying the frequency of particular DJH rearrangements (22) (Fig. 1 E and F). HTGTS-Rep-seq also could be adapted for revealing joining patterns of individual Ds or Vs by using them as baits. Thus, this assay, or adaptations of it, could be useful for detecting changes in repertoires that occur during development, or during an immune response. However, use of HTGTS-Rep-seq for assaying certain antigen receptor repertoires, most notably TCRα repertoires, would currently be more limited given the very large number of different Jαs (24).

HTGTS-Rep-seq requires as little as 100 ng of genomic DNA (and potentially less) from mouse splenic B cells to capture a representative profile of VH use. Thus, this technique can be applied to relatively small numbers of cells and yield accurate repertoire profiles. However, we find that much larger amounts of starting material would be required to capture the full extent of the immense complexity of the CDR3s that we demonstrate to exist in a given population of splenic B cells. Moreover, potential inaccuracies that do arise in quantifying certain rearrangements via HTGTS-Rep-seq, such as productive/nonproductive ratios for the Igκ repertoire, are due to inherent biological events that would be detected in other DNA-based repertoire-sequencing methods, such as nonproductive VJκ rearrangements in the genome in Igλ-expressing cells or sequential rearrangements involving inversional VJκ joining (34) (Fig. S6). This ambiguity in the assay for the Igκ locus could be minimized if desired by adding an initial step to enrich for sonicated DNA fragments containing sequences just downstream of the whole Jκ region.

The ability to use linear amplification with only a single J primer or set of J primers by HTGTS-Rep-seq avoids the necessity of using sets of degenerate V primers (along with J primers) required by prior DNA-based repertoire-sequencing methods, which could lead to variable amplification efficiencies of different V families or Vs within a family (15). Being DNA-based, HTGTS-Rep-seq also bypasses a major limitation of RNA-based methods for certain applications by quantitatively capturing the frequency of Ig rearrangements in a population regardless of their expression level or whether they are productive or nonproductive. Current means to address biases due to multiplex PCR or varying expression levels between cells include the use of universal identifiers (25, 36, 37) or single cell methods (38), but HTGTS-Rep-seq can accurately identify a population repertoire profile without the additional cost or steps of synthesizing primers with random barcodes, or sorting for single cells.

It is striking that, in experiments where we sequenced about 15,000 unique V(D)J rearrangements from each of three technical repeats, we found less than 1% overlap of unique CDR3 sequences, emphasizing the great sensitivity of the approach. This highly sensitive HTGTS-Rep-seq approach should easily be adapted for application to human samples. In that regard, the sensitivity of HTGTS-Rep-seq should provide a low cost and rapid method for identifying clonal rearrangements (even DJH rearrangements) that would be diagnostic of clonal B- or T-lymphocyte expansions that occur in the context of certain immune system diseases, including cancers. Finally, in our libraries, approximately one-third of our joined sequences cover the entire length of the ∼370-bp V(D)J exons, making HTGTS-Rep-seq applicable to tracking dominant populations of particular V(D)J exons, including particular CDRs, that appear in the B-cell repertoire during antibody affinity maturation in an immune response. This application may be enhanced as high throughput sequencing technologies are advanced to achieve greater lengths and accuracy.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

WT 129SVE and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories International. All animal experiments were performed under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston Children’s Hospital.

B-Cell Isolation from Bone Marrow and Spleen.

Bone marrow-derived pro-B (B220+IgM−CD43+) cells were purified from 129SVE or C57BL/6 mice by sorting and after the depletion of erythrocytes. Single cell suspensions were stained with B220-APC, CD43-PE, and IgM-FITC antibodies. Splenic resting B cells were purified using biotin/streptavidin bead methods (B220-positive selection) (130-049-501; Miltenyi) or EasySep negative B-cell selection (19754; Stem Cell Technologies).

HTGTS-Rep-Seq.

HTGTS-Rep-seq was performed as described (16). Primers are listed in Table S3. For the DJH joins analysis, we used the standard LAM-HTGTS bioinformatic pipeline (16). For the VHDJH and VJκ identification, we demultiplexed MiSeq reads using the fastq-multx tool in the ea-utils suite (https://code.google.com/archive/p/ea-utils) and trimmed adaptors with cutadapt software (https://cutadapt.readthedocs.io/en/stable/). The paired reads were then joined using the fastq-join tool from the ea-utils suite (overlap region ≥10 bp and mismatch rate ≤8%). Reads were then grouped as joined reads and unjoined and were analyzed separately in the following analysis. We used IgBLAST (23) using joined reads and unjoined reads against V(D)J gene databases using default parameters. The V(D)J gene sequences were obtained from IMGT (24), manually curated, and used to generate IgBLAST sequence databases. Various stringencies were applied to filter reads that can align to V, D, and J genes (IgBLAST score >150, total alignment length >100, overall mismatch ratio <0.1). In unjoined reads, the top V gene identified in R1 and R2 reads must match. The use of V genes can be computed based on the processed IgBLAST results. A pipeline named “HTGTSrep” was developed to conduct the above-mentioned processing and analyzing and can be downloaded at Bitbucket (https://bitbucket.org/adugduzhou/htgtsrep).

Table S3.

Oligos used for library construction

| Name | Sequence | Purpose |

| JH1-bio | /5BiosG/CTGCAGCATGCAGAGTGTG | HTGTS bio primer for JH1 coding end |

| JH1- red | TGACATGGGGAGATCTGAGA | HTGTS red primer for JH1 coding end |

| JH2- bio | /5BiosG/ACCCTTTCTGACTCCCAAGG | HTGTS bio primer for JH2 coding end |

| JH2- red | CCCCAACAAATGCAGTAAAATCT | HTGTS red primer for JH2 coding end |

| JH3- bio | /5BiosG/GGGACAAAGGGGTTGAATCT | HTGTS bio primer for JH3 coding end |

| JH3- red | CCCGTTTGCAGAGAATCTT | HTGTS red primer for JH3 coding end |

| JH4_bio | /5BiosG/CCCTCAGGGACAAATATCCA | HTGTS bio primer for JH4 coding end |

| JH4 _red | CTGCAATGCTCAGAAAACTCC | HTGTS red primer for JH4 coding end |

| Jκ1_bio | /5Biosg/TTCCCAGCTTTGCTTACGGAG | HTGTS bio primer for Jκ1 coding end |

| Jκ1_ red | AGTGCCAGAATCTGGTTTCAGAG | HTGTS red primer for Jκ1 coding end |

| Jκ2_bio | /5Biosg/ATTCCAACCTCTTGTGGGACAG | HTGTS bio primer for Jκ2 coding end |

| Jκ2_ red | TCCCTCCTTAACACCTGATCTGAG | HTGTS red primer for Jκ2 coding end |

| Jκ4_bio | /5BiosG/CGCTCAGCTTTCACACTGACTC | HTGTS bio primer for Jκ4 coding end |

| Jκ4_ red | CAGGTTGCCAGGAATGGCTC | HTGTS red primer for Jκ4 coding end |

| Jκ5_bio | /5Biosg/GCCCCTAATCTCACTAGCTTGA | HTGTS bio primer for Jκ5 coding end |

| Jκ5_ red | GTCAACTGATAATGAGCCCTCTCC | HTGTS red primer for Jκ5 coding end |

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the F.W.A. laboratory for stimulating discussions and Dr. Richard Frock for experimental advice. This work is supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01AI020047 (to F.W.A.) and Grant F31-AI117920 (to S.G.L.). Z.B. is supported by a Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellowship; J.H. by a Robertson Foundation/Cancer Research Institute Irvington Fellowship; and Y.Z. by a career development fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. F.W.A. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The sequencing and processed data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE82126).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1608649113/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Teng G, Schatz DG. Regulation and Evolution of the RAG Recombinase. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:1–39. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alt FW, Zhang Y, Meng F-L, Guo C, Schwer B. Mechanisms of programmed DNA lesions and genomic instability in the immune system. Cell. 2013;152(3):417–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alt FW, Baltimore D. Joining of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene segments: Implications from a chromosome with evidence of three D-JH fusions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79(13):4118–4122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.13.4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Retter I, et al. Sequence and characterization of the Ig heavy chain constant and partial variable region of the mouse strain 129S1. J Immunol. 2007;179(4):2419–2427. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.4.2419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yancopoulos GD, Alt FW. Regulation of the assembly and expression of variable-region genes. Annu Rev Immunol. 1986;4:339–368. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.04.040186.002011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proudhon C, Hao B, Raviram R, Chaumeil J, Skok JA. Long-range regulation of V(D)J recombination. Adv Immunol. 2015;128:123–182. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung D, Giallourakis C, Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW. Mechanism and control of V(D)J recombination at the immunoglobulin heavy chain locus. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:541–570. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guo C, et al. CTCF-binding elements mediate control of V(D)J recombination. Nature. 2011;477(7365):424–430. doi: 10.1038/nature10495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin SG, Guo C, Su A, Zhang Y, Alt FW. CTCF-binding elements 1 and 2 in the Igh intergenic control region cooperatively regulate V(D)J recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(6):1815–1820. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424936112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuxa M, et al. Pax5 induces V-to-DJ rearrangements and locus contraction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Genes Dev. 2004;18(4):411–422. doi: 10.1101/gad.291504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jhunjhunwala S, et al. The 3D structure of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain locus: Implications for long-range genomic interactions. Cell. 2008;133(2):265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melchers F. Checkpoints that control B cell development. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(6):2203–2210. doi: 10.1172/JCI78083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granato A, Chen Y, Wesemann DR. Primary immunoglobulin repertoire development: Time and space matter. Curr Opin Immunol. 2015;33:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2015.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schroeder HW, Jr, Zemlin M, Khass M, Nguyen HH, Schelonka RL. Genetic control of DH reading frame and its effect on B-cell development and antigen-specifc antibody production. Crit Rev Immunol. 2010;30(4):327–344. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i4.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Georgiou G, et al. The promise and challenge of high-throughput sequencing of the antibody repertoire. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(2):158–168. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu J, et al. Detecting DNA double-stranded breaks in mammalian genomes by linear amplification-mediated high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(5):853–871. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiarle R, et al. Genome-wide translocation sequencing reveals mechanisms of chromosome breaks and rearrangements in B cells. Cell. 2011;147(1):107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frock RL, et al. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33(2):179–186. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng F-L, et al. Convergent transcription at intragenic super-enhancers targets AID-initiated genomic instability. Cell. 2014;159(7):1538–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wei P-C, et al. Long neural genes harbor recurrent DNA break clusters in neural stem/progenitor cells. Cell. 2016;164(4):644–655. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dong J, et al. Orientation-specific joining of AID-initiated DNA breaks promotes antibody class switching. Nature. 2015;525(7567):134–139. doi: 10.1038/nature14970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu J, et al. Chromosomal loop domains direct the recombination of antigen receptor genes. Cell. 2015;163(4):947–959. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ye J, Ma N, Madden TL, Ostell JM. IgBLAST: An immunoglobulin variable domain sequence analysis tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41(Web Server issue):W34–W40. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lefranc M-P, et al. IMGT®, the international ImMunoGeneTics information system® 25 years on. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(Database issue):D413–D422. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan TA, et al. Accurate and predictive antibody repertoire profiling by molecular amplification fingerprinting. Sci Adv. 2016;2(3):e1501371. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alt FW, et al. Ordered rearrangement of immunoglobulin heavy chain variable region segments. EMBO J. 1984;3(6):1209–1219. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1984.tb01955.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daly J, Licence S, Nanou A, Morgan G, Mårtensson I-L. Transcription of productive and nonproductive VDJ-recombined alleles after IgH allelic exclusion. EMBO J. 2007;26(19):4273–4282. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yancopoulos GD, et al. Preferential utilization of the most JH-proximal VH gene segments in pre-B-cell lines. Nature. 1984;311(5988):727–733. doi: 10.1038/311727a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malynn BA, Yancopoulos GD, Barth JE, Bona CA, Alt FW. Biased expression of JH-proximal VH genes occurs in the newly generated repertoire of neonatal and adult mice. J Exp Med. 1990;171(3):843–859. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.3.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.ten Boekel E, Melchers F, Rolink AG. Changes in the V(H) gene repertoire of developing precursor B lymphocytes in mouse bone marrow mediated by the pre-B cell receptor. Immunity. 1997;7(3):357–368. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80357-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schatz DG, Ji Y. Recombination centres and the orchestration of V(D)J recombination. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(4):251–263. doi: 10.1038/nri2941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gorman JR, Alt FW. Regulation of immunoglobulin light chain isotype expression. Adv Immunol. 1998;69:113–181. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60607-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mostoslavsky R, Alt FW, Rajewsky K. The lingering enigma of the allelic exclusion mechanism. Cell. 2004;118(5):539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melchers F, ten Boekel E, Yamagami T, Andersson J, Rolink A. The roles of preB and B cell receptors in the stepwise allelic exclusion of mouse IgH and L chain gene loci. Semin Immunol. 1999;11(5):307–317. doi: 10.1006/smim.1999.0187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pieper K, Grimbacher B, Eibel H. B-cell biology and development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(4):959–971. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vollmers C, Sit RV, Weinstein JA, Dekker CL, Quake SR. Genetic measurement of memory B-cell recall using antibody repertoire sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(33):13463–13468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1312146110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Egorov ES, et al. Quantitative profiling of immune repertoires for minor lymphocyte counts using unique molecular identifiers. J Immunol. 2015;194(12):6155–6163. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1500215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundling C, et al. Single-cell and deep sequencing of IgG-switched macaque B cells reveal a diverse Ig repertoire following immunization. J Immunol. 2014;192(8):3637–3644. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]