Abstract

Recent advancements in material science and engineering may hold the key to overcoming reproducibility and scalability limitations currently hindering the clinical translation of stem cell therapies. Biomaterial assisted differentiation commitment of stem cells and modulation of their in vivo function could have significant impact in stem cell-centred regenerative medicine approaches and next gen technological platforms. Synthetic biomaterials are of particular interest as they provide a consistent, chemically defined, and tunable way of mimicking the physical and chemical properties of the natural tissue or cell environment. Combining emerging biomaterial and biofabrication advancements may finally give researchers the tools to modulate spatiotemporal complexity and engineer more hierarchically complex, physiologically relevant tissue mimics. In this review we highlight recent research advancements in biomaterial assisted pluripotent stem cell (PSC) expansion and three dimensional (3D) tissue formation strategies. Furthermore, since vascularization is a major challenge affecting the in vivo function of engineered tissues, we discuss recent developments in vascularization strategies and assess their ability to produce perfusable and functional vasculature that can be integrated with the host tissue.

1. Introduction

The advent of the tissue engineering field brought great promise in advancing regenerative medicine(1), drug screening and pathophysiologically relevant disease modelling(2). Decades later, still faced with increasing organ shortages and drug-screening discrepancies, any clinically relevant success in the field have been limited. Even though tissue specific cells (somatic cells and tissue specific stem cells) have been marginally successful in creating engineered tissues by recapitulating certain physiologically relevant structural and functional attributes, they are in limited supply and have limited in vitro expansion capabilities. On the other hand, human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs), which include human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), exhibit unlimited expansion potential in vitro and have the ability to differentiate into all cell types in the human body, making them an ideal cell source(3). Additionally, because hiPSCs can be derived from patient's own cells, new frontiers in personalized medicine can be explored.

Successful application of pluripotent stem cells for regenerative medicine relies on our ability to grow them in vitro without any karyotypic instability, acquire large number of cells and direct their differentiation in a tissue specific manner, as well as achieve in vivo integration and function upon transplantation. While conventional approaches involving growth factors and soluble molecules have been widely used to control stem cell commitment, recent advances in the field of biomaterials have led to new strategies to control stem cell fate(4). Studies over the years have shown that the architecture, interfacial properties (hydrophobicity, topography), mechanical properties, and chemical properties of the biomaterials could play a pivotal role in stem cell fate determination(4-14). Though biomaterial-based strategies have been used to achieve stem cell differentiation; successfully engineering large and hierarchically complex three-dimensional (3D) tissues would require complex biomaterial design and incorporation of multiple cell types as well as vascularization of the tissues upon transplantation.

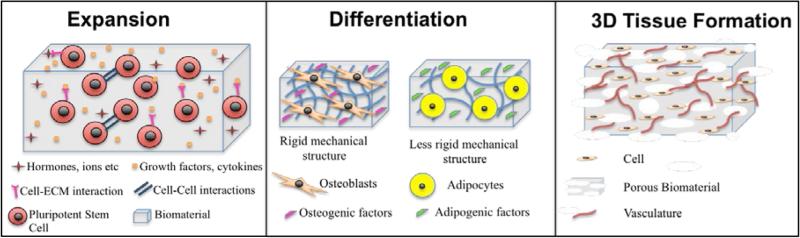

Pluripotent stem cells could contribute to regenerative medicine in a myriad of ways including contributing to tissue repair (cell transplantation and 3D tissue engineered implants)(15-17), as a technological platform towards improving drug discovery(18-20), identifying small molecules to improve stem cell lineage specificity(21) and recapitulating pathophysiology of various diseases (disease-in-a-dish). Both natural and synthetic biomaterials have been used as artificial extracellular matrices (ECM) to improve expansion and differentiation of stem cells as well as 3D tissue formation (Fig.1). While natural materials are the obvious choice as they intrinsically provide the necessary biochemical cues, they often suffer from weak mechanical properties, poor reproducibility, high cost and short shelf life. On the contrary, synthetic biomaterials may be more advantageous because they can be chemically and mechanically tuned, easily sterilized, reproduced, scaled and they have a longer shelf life and lower immunogenicity.

Figure 1.

Schematic Overview of the contribution of biomaterials for the expansion, differentiation and 3D tissue formation of pluripotent stem cells.

In this review, we first identify efforts in biomaterial-based expansion of hPSCs because before clinical translation of hPSC-based therapies can be achieved, reproducible expansion and differentiation techniques must be established. Then we summarize recent biomaterial-assisted stem cell engineering developments, with a specific focus on skeletal (cartilage and bone) and cardiac tissues, and vascularization of engineered 3D tissue constructs.

2. Biomaterial Assisted Expansion of Stem Cells

The success and scalability of stem cell-based bioengineering strategies hinges on the supply of a reproducible and extensive cell source. Clinical translation of these strategies requires well-defined expansion of cells. However, many of the conventional expansion protocols utilize mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)(22) or Matrigel(23) as feeder layers. While these feeder layers are efficient in supporting self-renewal of hPSCs, they could potentially transmit pathogens or non-human contaminants (e.g. N-glycolylneuraminic acid), thereby creating a safety hazard(24, 25). Though mechanically separating the feeder layer from the hPSCs could be a potential solution to limit such contaminant transfer, Kim et al showed that cocultures of the two cells by using porous membranes (where the membrane was used to eliminate cell-cell contact between the two cell types) could only decrease, but not eliminate, mouse vimentin gene expression in the hESCs(26). Thus, there is a great need for chemically defined culture conditions. This has led to active research in the identification of various peptides, components of ECM proteins (recombinant proteins), and synthetic biomaterials such as polymers to replace feeder layers in the support of in vitro expansion of hPSCs. Some of these strategies include coating or conjugating the tissue culture plates with peptides, ECM proteins, and/or synthetic polymers(27-29).

Given the propensity of ECM proteins to foster cell-matrix interactions, different ECM proteins have been actively studied. Laminin isoform LN-521/E-cadherin matrices have been demonstrated as a promising alternative for Matrigel(27). Similarly, vitronectin has been shown to support long-term hPSC expansion in vitro(28) and hence tissue culture surfaces modified with vitronectin- and RGD- moieties are already commercially available as Synthemax™. Although ECM proteins are ideal for mediating cell-matrix interactions necessary for cell adhesion and growth, they are not an ideal candidate due to their sensitivity to environmental parameters such as temperature and pH (ECM proteins can denature responding to temperature and pH fluctuations) and are often cost prohibitive. Using synthetic peptides, polymers, and combinations thereof has been evaluated to circumvent these limitations. Studies have shown that surfaces modified with vitronectin-based(29, 30) and bone sialoprotein-based(30) peptides along with RGD, ligands that facilitate cell adhesion to the underlying matrices, supported self-renewal of hPSCs in vitro while maintaining their pluripotency and karyotypic stability(29). Similarly, surfaces modified with synthetic polymers have also been shown to support self-renewal of hPSCs in vitro(31-33). However, such surface modifications require additional manufacturing steps and hence may be cost prohibitive.

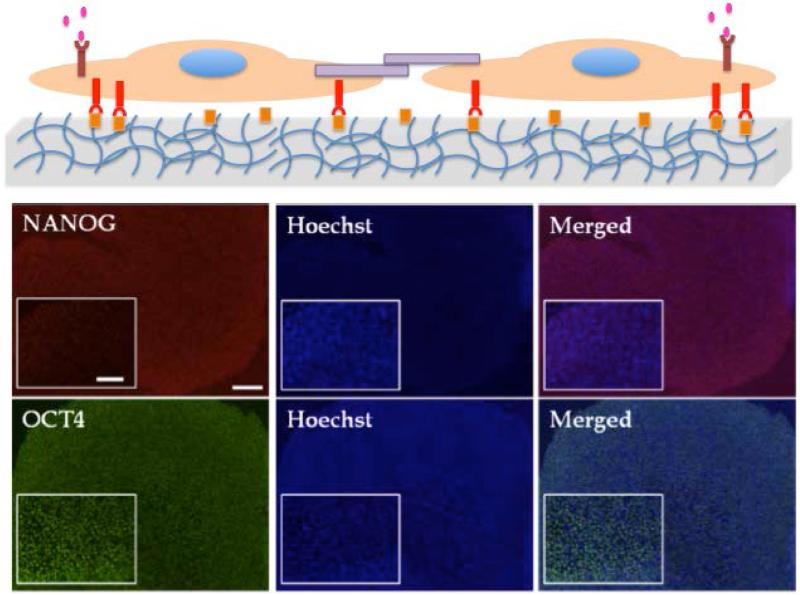

Alternatively, synthetic hydrogels may provide easy to synthesize and reproducible matrices for hPSC expansion. Unlike substrates such as tissue culture (TC) plates, the mechanical and chemical properties of the hydrogels can be easily tuned, as needed. Our group has demonstrated that poly(acrylamide) hydrogels modified with poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS) units (PAm-PSS) can activate cellular processes and harness autocrine factors to support self renewal of hPSCs and sustain their long term growth (≥20passages) without compromising karyotypic stability and pluripotencey (Fig. 2)(33). Another chemically defined synthetic hydrogel, poly[2(methacryloyloxy) ethyl dimethyl-(3-sulfopropyl) ammonium hydroxide] (PMEDSAH) showed similar ability to promote long term hPSC growth(34). Similarly, studies by Irwin et al have shown the potential of aminopropylmethacrylamide (APMAAm)-based hydrogel interfaces to promote expansion and pluripotency maintenance of hESCs in chemically defined mTeSR™ media(35).

Figure 2.

Biomaterial assisted expansion of human pluripotent stem cells. Top panel, schematic of cell expansion on synthetic PSS hydrogel. Middle and Bottom panel, Immunoflourescent staining of PAm-PSS hydrogels supported in vitro growth of HUES6 cells after 7 passages. Red NANOG, green OCT4, blue Hoechst stained nuclei. Scale bar 200μm main image and inset 100μ m. Adapted and reprinted from Chang C-W. et al(33) with permission from Biomaterials.

Surface properties (hydrophobicity, surface topography, functional groups and charge) and bulk properties (such as stiffness) of the biomaterials play an important role in determining the cell-matrix and cell-cell adhesions. Research throughout the years has implied the importance of many biomaterial properties hydrophobicity (or hydrophilicity), functional groups, and matrix stiffness in supporting self-renewal of hPSCs (4-14). However, these findings do not ensure that the observed cellular behaviours are solely attributed to a single factor and not the result of interplay of multiple interdependent and convoluted physical and chemical properties of the biomaterial.

An optimal cell-matrix interaction that supports colony formation of cells is necessary to maintain pluripotency of hPSCs. In the absence of any adhesive moiety, such as protein or peptide conjugation, the physicochemical properties of the biomaterial play a key role in supporting cell adhesion mostly through non-specific adsorption of proteins from the culture medium and/or sequestration of cell secreted ECM proteins and growth factors. In addition to mediating the attachment of cells to the underlying substrate, the biomaterial properties also contribute to cell shape determination. Both the amount and conformation of proteins and biomolecules at the cell-matrix interface provide the biological cues to determine the stem cell fate. For instance, the study by Chang et al.(33) have used hydrogels bearing PSS molecules, a synthetic analogue of heparin, for the ex vivo expansion of pluripotent stem cells. Similar to heparin, PSS molecules have been shown to bind to bFGF molecules, a crucial growth factor required for maintenance of self-renewal of hPSCs in vitro, and modulate their bioactivity.

The 2D culture method is widely used for hPSC expansion because it allows easy cell retrieval through conventional enzyme digestion such as trypsinization. However, 2D cultures lack many spatiotemporal cues (of the ECM) that 3D culture formats provide(36-38). Such spatiotemporal cues could improve efficacy and yield of hPSC expansion significantly (39). Since the retrieval of cells from 3D cultures (involving 3D scaffolds embedded with cells) requires complete degradation of the scaffold without introducing any detrimental effect to the embedded cells; relying on traditional degradation methods such as enzymatic and hydrolytic degradation may not be conducive for cell retrieval. To this end, stimuli responsive biomaterials like thermoresponsive polymers that exhibit sol-gel transition(40) around physiologically relevant temperatures could offer some solutions. In fact, a recent study by Lei et al has used thermoresponsive hydrogels as scaffolds to support in vitro expansion of hPSCs and facilitate easy cell retrieval by simply changing temperature (39). Specifically, the authors have used poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)-co-poly(ethylene glycol) (PNIPAAm-PEG) to support hPSC culture at 37°C. Upon lowering the temperature to 4°C, the scaffolds undergo gel to solution transition to release the cells. The authors have shown that the hPSCs cultured under optimal conditions within PNIPAAm-PEG hydrogels resulted in 20-fold cell expansion in just 4-5 days and 1072 fold expansion in 280 days (around 60 passages). This study exemplifies the advantages of 3D cultures over the conventional 2D formats.

It is well established that 3D cultures in suspension yield higher cell numbers compared to 2D adherent cultures. Hence, 3D culture offers scalable and efficient culture platforms to generate large numbers of cells required for various applications, thus contributing significantly to stem cell manufacturing. Furthermore, since 3D cultures could support exponential growth of hPSCs in comparable culture media (both amount and composition) to the media used in 2D cultures, this would make 3D cultures substantially more cost-effective, which is key to improving the translational potential of hPSCs. Additionally, 3D systems could yield a more homogenous cell population compared to 2D cultures especially if the cultures were beginning with small cell numbers.

3. Biomaterial assisted 3D tissue formation through hPSC differentiation and organization

Beyond enabling in vitro growth of cells, biomaterial-based technologies have been used to direct differentiation of stem cells (Table 1) and as an instructive scaffold to support functional 3D tissue formation(36). Studies that use hPSCs as a cell source to create 3D skeletal or cardiac tissues can be generally categorized by either employing hPSCs or hPSC-derivatives. In vitro differentiation or pre-conditioning of hPSCs prior to implantation can be more advantageous in promoting in vivo survival and engraftment of transplanted cells. Using differentiated cells also limits potential teratoma formation (41, 42), which is a serious safety issue impeding the prospect of clinical translation of pluripotent stem cell-based therapies. In addition to pre-conditioning the cells prior to transplantation, biomaterials have also been used as a delivery vehicle to improve the functional outcome of cell transplantation(43-46).

Table 1.

Overview of natural and synthetic biomaterials for stem differentiation

| Biomaterial | Natural or Synthetic | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fibrillar collagen | Natural | Pluripotent stem cell differentiation into MSC-like cells | [48] |

| poly(l-lactic acid)/poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLLA/PLGA) | Synthetic | Chondrogenic differentiation | [52] |

| Hyaluronan | Natural | Chondrogenic differentiation | [53] |

| Alginate | Natural | Chondrogenic differentiation | [51] |

| Poly(caprolactone) (PCL) | Synthetic | Osteogenic differentiation | [54] |

| Decellularized bovine bone | Natural | Osteogenic differentiation | [55] |

| Mineralized gelatin methacrylate | Synthetic | Osteogenic differentiation | [56-58] |

| Fibrin | Natural | Cardiomyocyte differentiation | [59] |

| Collagen gels or matrices | Natural | Cardiomyocyte differentiation | [62, 63] |

| poly(glycerol sebacate) (PGS) | Synthetic | Cardiomyocyte differentiation | [67] |

3.1 Skeletal Tissue

Engineering elements of the musculoskeletal system demands 3D tissue replacements that can structurally support load, accommodate stresses, and facilitate movement. The inevitable wear and tear of the aging musculoskeletal system places a constant demand on the need for cartilage and bone replacements and new therapeutic strategies to repair the compromised tissues. The physiochemical properties of biomaterials have been used both towards promoting early commitment (derivation of mesenchymal like progenitor cells) and also towards achieving terminal differentiation (e.g. hPSCs to osteoblasts) of hPSCs(47). For instance, fibrillar collagen scaffolds, devised to mimic the physiological structure of collagen present in native tissue, were used by Liu et al to seed both hiPSCs and hESCs and demonstrate that substrate physiochemical properties were sufficient to derive MSC-like mesoderm progenitor cells with adipogenic, osteogenic, and chondrogenic differentiation capacities(48). While a number of studies have used such hPSC-derived MSC-like cells as precursors (48, 49), there also exist reports that directly used hPSCs to create cartilage and bone tissues(50, 51).

For example, biomaterial supported 3D cultures that can control cell shape and promote mesenchymal condensation of cells, have been used to achieve chondrogenic commitment of stem cells and progenitor cells(52). Levenberg et al showed that a combination of poly(l-lactic acid)/poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLLA/PLGA) scaffold with transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) could promote chondrogenic differentiation of hESCs(52). In another study, Bigdeli et al used hyaluronan-based scaffolds to facilitate chondrogenic differentiation of a coculture of undifferentiated hESCs with human adult chondrocytes(53). Results indicated that in two weeks cells showed increased chondrogenic differentiation as evidenced by the production of cartilage specific extracellular matrices. In a similar approach, Wei et al used an alginate matrix to promote chondrogenic differentiation of cocultured (with chondrocytes) iPSCs, derived from osteoarthritic chondrocytes. (51). The group demonstrated not only that they could successfully reprogram human osteoarthritic chondrocytes into iPSCs but that they could also promote chondrogenic differentiation of the generated iPSCs. In both these coculture studies biomaterials played an integral role in promoting cell-cell interactions and serving as a reservoir of secreted factors that promote chondrogenic differentiation of the pluripotent stem cells.

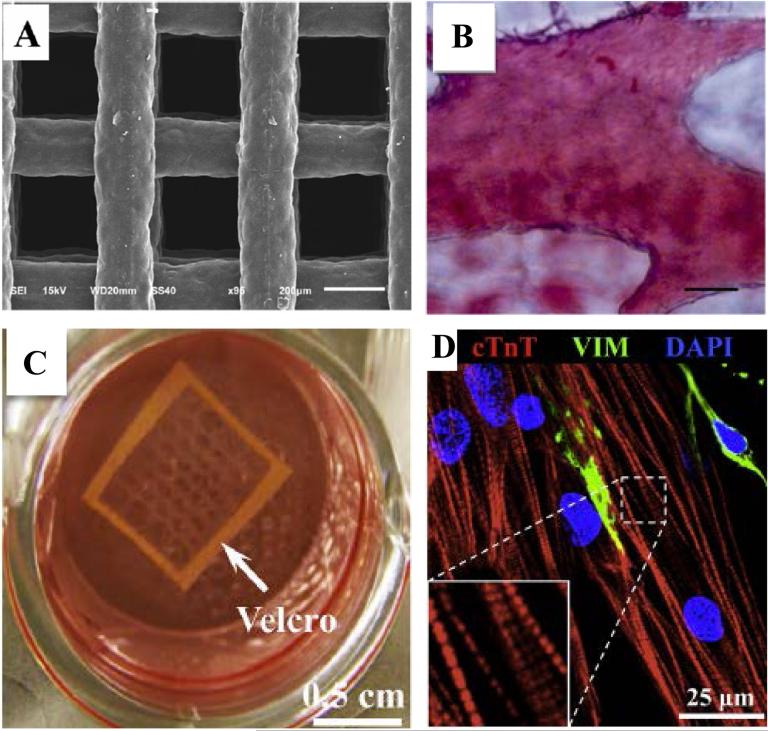

Osteogenic differentiation was studied by groups like Jin et al who cultured hiPSCs in poly(caprolactone) (PCL) scaffolds (Fig. 3A) to promote osteogenesis by the addition of exogenous osteogenic factors(54). After 4 weeks of subcutaneous implantation they demonstrated that ECM and mineral deposition within the scaffold was indicative of bone formation (Fig. 3B) and could be achieved without the use of an embryoid body step. While many studies have used a combination of biomaterials and growth factors towards differentiation, de Peppo et al have used biological materials, such as decellularized bovine bone, to achieve osteogenic differentiation of the hiPSC-derived MSC-like cells (55). The hiPSC-seeded scaffolds facilitated osteogenic differentiation and bone tissue formation of hiPSC-derived MSC-like cells in a bioreactor. After 5 weeks in the bioreactor, constructs were subcutaneously implanted in mice for 12 weeks. Subsequent analysis demonstrated mature bone like tissue formation and evidence of osteoclast recruitment and vascularization. Another recent sans growth factor study has shown that synthetic biomaterials recapitulating the mineral environment (calcium phosphate minerals) of bone tissue can be used to direct osteogenic differentiation of hPSCs to result in 3D bone tissue formation (56, 57). In addition to supporting differentiation, these mineralized biomaterials (e.g. Mineralized Polyethylene (glycol) Diacrylate) formed vascularized bone tissue when implanted in vivo(58).

Figure 3.

Biomaterial Assisted 3D tissue formation. A. SEM microphotograph of porous PCL scaffold used for bone tissue engineering. B. Alizarin red S staining indicating calcified ECM of PCL porous scaffold containing hiPSC-derived osteoblasts. (Scale bar 40μm) Adapted and reprinted from Jin et al(54) with permission from Journal of Biomedical Materials Research. C. Fibrin based cardiac patch tethered with Velcro frame. D. Aligned 3D cardiac tissue patch with cross-striated cardiac Troponin (cTnT) expression. (VIM=vimentin positive fibroblasts). Adapted and reprinted from Zhang et al(59) with permission from Biomaterials.

Though a number of different biomaterials have been used to assist osteogenic differentiation, most of these approaches required a cooperative or synergetic effect of biomaterials along with osteogenic inducing soluble factors. In contrast, our studies showed that mineralized biomaterials containing calcium phosphate minerals assist osteogenic differentiation of hESCs and hiPSCs in growth medium devoid of any osteogenic inducing soluble factors(58). This finding suggests that the sole use of mineralized materials is sufficient to direct osteogenic commitment of hPSCs to form 3D bone tissues both in vitro and in vivo.

3.2 Cardiac Tissue

Biomaterials have been extensively used in cardiac tissue engineering both in vitro and in vivo(60, 61). Most of these studies utilize cardiomyocytes or cardiac progenitor cells derived from hPSCs to form 3D cardiac tissues. Chen et al have used an elastomeric polymer, poly (glycerol sebacate) (PGS), as a scaffold to generate cardiac tissue patches from hESC derived cardiomyocytes (62). When implanted in vivo the engineered cardiac patches remained intact after being sutured over the left ventricle of rats and did not negatively impact the ventricular function. Studies have also integrated mechanical cues along with biomaterials to create cardiac tissues emulating the alignment observed in native tissue. Zhang et al. have tethered cell-laden fibrin gels to a Velcro frame (Fig. 3C) to mechanically induce alignment of cardiac tissues (Fig. 3D) (59). The hESC-derived cardiomyocytes cultured using this setup enabled formation of tissues with high electrical propagation and contractile force generation. Furthermore, the engineered cardiac patch demonstrated positive inotropy with isoproterenol treatment, which is indicative of cardiomyocyte maturation. Similarly, hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes cultured using collagen matrices and subjected to uniaxial mechanical loading has been shown to significantly enhance myofibrillogenesis and sarcomeric banding of the cellular constructs(63). Tulloch et al also used the same 3D culture system to incorporate cell-cell communications by coculturing the hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes with endothelial cells and stromal cells. This not only enhanced cardiomyocyte proliferation rates but also led to in vivo engraftment and microvessel perfusion upon transplantation onto athymic rat hearts.

Nunes et al, in an alternative approach, used an electrically stimulated “biowire” to induce maturation and alignment of hPSC-derived cardiomyocytes(64). In this technique a linear suture template was used to facilitate organization of the encapsulated stromal cells and the cardiomoyocytes within collagen type I hydrogels. Electrical stimulation of these cell-laden structures led to increased myofibril organization and enhanced contractile and electrical properties compared to non-stimulated controls. Subsequent work, by the same group and others, has indicated that a combination of electrical stimulation and mechanical conditioning plays an important role in stem cell differentiation towards cardiac cells as well as cardiac tissue maturation(65, 66). Biomaterials can contribute significantly to this effort by facilitating the integration of electrical and mechanical cues in 3D stem cell cultures(67). One such multi-functional biomaterial could be electric field responsive hydrogels wherein the hydrogels undergo reversible stretching/bending in response to external electric field, thereby providing multiple physicochemical cues to the encapsulated cells.

4. Vascularization of engineered tissues

While significant developments can be made through the integration of biomaterial and hPSC-based approaches to engineer more complex tissues, the overall growth of the field is still stunted by poor tissue vascularization and in vivo integration. Though relatively successful on a small scale, engineering larger, more metabolically demanding tissues like the liver, heart, pancreas, bone, and kidney that adhere to diffusion limitations within 100-200μ m(68) has remained illusive. In the absence of a perfusable nutrient rich oxygen supply, engineered tissues quickly develop necrotic cores, making their long-term survival and integration with the host tissue challenging. Thus, a great impetus has been placed on biomaterial fabrication as a major vehicle to facilitate vascularization. As such, researchers are exploring different avenues like porous scaffold design, bio printing, and functionalization to promote vascularization.

Successful in vivo engineered tissue vascularization requires space within the scaffold for host cell infiltration and vessel ingrowth after implantation. Porous scaffolds, especially with interconnected pores, have been found to promote efficient host cell infiltration and vascularization of the implant(69, 70). Particle leaching, freeze-drying and other techniques commonly produce these porous scaffolds. While these approaches are sufficient to create scaffolds with varying pore sizes, they often result in random pore organization and poor interconnectivity. Now, the advent of solid free form fabrication systems allows controlled generation of more defined pore architecture, through computer-aided design (CAD), to reproduce desired scaffold porosity and interconnectivity(71, 72). Incorporation of proangiogenic growth factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) into scaffolds has also been used to promote further vascularization(73). However, since high growth factor dosage can result in vascular leakage and hypotension(73) researchers have tried replacing exogenously added growth factors with cell types that could release these factors in a more controlled manner. As such, successful attempts have been made to seed porous scaffolds with endothelial cells before implantation to speed up vessel formation(74).

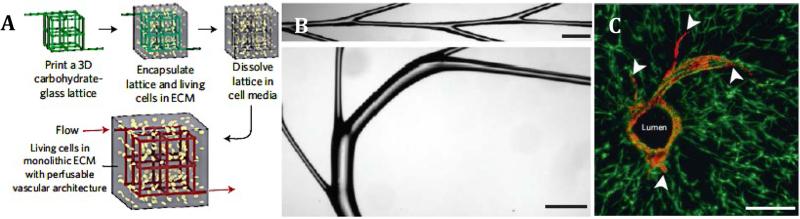

New fabrication methods such as micropatterning(75, 76) and 3D printing(77) are also being used rapidly to promote vascularization. These approaches have the potential to produce intricately designed vasculature in a high throughput manner(78). Recently, many studies have combined 3D printing and sacrificial layers to generate hollow-tubular structures that can be exogenously populated with cells or have the potential to facilitate recruitment of endogenous cells and subsequent anastomosis of the implant with the host tissue. For example, Kolesky et al have demonstrated a method to produce spatially separated, multicellular, vascularized 3D tissues by using gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) based cell inks to print two different cell types along with temperature sensitive sacrificial vascular network structures (Pluronic F127 layer) all encased within a chemically crosslinked gelatin network (79). The sol-gel transition of the Pluronics at 4°C converted the sacrificial layer to a liquid phase, which was washed away, leaving behind a hollow, tubular vascular framework. Subsequent perfusion of the structures with exogenous HUVECs showed successful lumen formation. In a rapid casting method, Miller et al 3D printed carbohydrate-glass sacrificial vasculature networks which were then encapsulated with cells within various different ECM mimics (Fig. 4)(78). They too showed successful perfusion and lumen formation in addition to vessel sprouting. However, even though both methods can potentially have many in vitro applications, whether they can form functional vasculature that can be successfully integrated in vivo has yet to be seen.

Figure 4.

Vascularization Strategies. A. Schematic overview of rapid casting sacrificial layer printing and subsequent dissolving. B. Rapid casting of branched filaments (scale bar 1mm). C. Endothelial cell (red) lumen formation and sprouting (white arrows) from patterned vasculature (scale bar 200μm). Adapted and reprinted from Miller et al(78) with permission from Nature Materials.

Like these studies, any future developments in sacrificial layer vascularization approaches must take precautions to mitigate cell exposure to changes in osmolarity or toxic byproducts, resulting from the dissolution of the sacrificial layer, that could have detrimental effect on the cells’ function or viability. Additionally, to facilitate the widespread successful application of 3D printing for vascularization applications, improvements must be made to increase the resolution, ease of use, adaptability, number of cytocompatible biomaterials that can be used as sacrificial layers and printing speed in order to improve cell viability during future scaling up attempts.

5. Conclusions and Perspective

Any chance of successful translation of cell and tissue engineering approaches from bench top to bedside demands substantial cell sources and vascularization of engineered tissues upon transplantation. While researchers are getting closer, reproducibly producing pure differentiated cell populations from hPSCs remains a serious issue, as the presence of undifferentiated hPSC progeny have been known to form teratomas(41, 42). Hence, it is important to ensure complete and irreversible differentiation of hPSCs into the desired phenotypes. Tissue specific differentiation of hPSCs can be achieved by exposing them to necessary soluble and insoluble (biomaterial based) cues. Emerging evidences suggest that the physicochemical properties of the biomaterial could be very powerful in controlling various cellular functions ranging from adhesion to differentiation. Leveraging that various tissues in the human body exhibit inherently different mechanical properties, biomaterials were designed to mimic the tissue specific mechanical environment. These attempts have established the importance of the elasticity of biomaterials in promoting stem cell differentiation. Similarly, tissue specific chemical environment of the biomaterial also plays a pivotal role in directing stem cell differentiation. Hence, biomaterials have been developed to mimic tissue specific mechanical, chemical, and topographical cues to direct stem cell differentiation. While these developments have offered new understanding and opened up exciting avenues, substantial work remains to elucidate the dependence of cellular response to various physicochemical cues of the biomaterials individually and in concert. Equally important is unraveling the underlying mechanism through which the biomaterial properties exert specific cellular functions.

Nonetheless, these advancements in the field of functional biomimetic materials (recapitulating tissue specific physicochemical cues), along with biofabrication has led to significant progress in creating functional 3D tissues. For instance, integration of biomaterial technologies along with micro-fabrication could circumvent the current limitation in tissue architecture determination and vascularization. Thus, there is no doubt that novel methods at the interface of biomaterial manipulation, stem cell engineering and micro-fabrication have and will continue to be successfully used to propel the advancement of pluripotent stem cell fate determination and development of more physiologically relevant engineered tissue.

Harnessing the ability of hPSCs to differentiate into multiple cell types could significantly contribute to the generation of multicellular, multifunctional, hierarchically complex tissues. Tissue engineering approaches to create these 3D tissue surrogates will not only contribute to tissue and organ repair but will also improve healthcare as the same principles can be employed to recapitulate pathophysiological characteristics and the morphogenesis of organs. The ability to recapitulate the pathophysiological function of the organs in vitro can lead to major breakthroughs in disease modelling and drug discovery.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the funding support of the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (5R01 AR063184-02) and California Institute of Regenerative Medicine (RT3-07907). N.M.S. acknowledges the funding support of the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship Program.

References

- 1.Smith AG. Embryo-derived stem cells: of mice and men. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 2001;17:435–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alison MR. Stem cells in pathobiology and regenerative medicine. The Journal of pathology. 2009;217(2):141–3. doi: 10.1002/path.2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, et al. Embryonic Stem Cell Lines Derived from Human Blastocysts. Science. 1998;282(5391):1145–7. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Discher DE, Mooney DJ, Zandstra PW. Growth Factors, Matrices, and Forces Combine and Control Stem Cells. Science. 2009;324(5935):1673–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1171643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Downing TL, Soto J, Morez C, Houssin T, Fritz A, Yuan F, et al. Biophysical regulation of epigenetic state and cell reprogramming. Nat Mater. 2013;12(12):1154–62. doi: 10.1038/nmat3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gurdon JB, Bourillot PY. Morphogen gradient interpretation. Nature. 2001;413(6858):797–803. doi: 10.1038/35101500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin S, Sangaj N, Razafiarison T, Zhang C, Varghese S. Influence of Physical Properties of Biomaterials on Cellular Behavior. Pharm Res. 2011;28(6):1422–30. doi: 10.1007/s11095-011-0378-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ayala R, Zhang C, Yang D, Hwang Y, Aung A, Shroff SS, et al. Engineering the cell–material interface for controlling stem cell adhesion, migration, and differentiation. Biomaterials. 2011;32(15):3700–11. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burdick JA, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Engineered Microenvironments for Controlled Stem Cell Differentiation. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2008;15(2):205–19. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matrix Elasticity Directs Stem Cell Lineage Specification. Cell. 2006;126(4):677–89. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benoit DSW, Schwartz MP, Durney AR, Anseth KS. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nat Mater. 2008;7(10):816–23. doi: 10.1038/nmat2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phillips JE, Petrie TA, Creighton FP, García AJ. Human mesenchymal stem cell differentiation on self-assembled monolayers presenting different surface chemistries. Acta Biomaterialia. 2010;6(1):12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2009.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, et al. Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate. Nat Mater. 2010;9(6):518–26. doi: 10.1038/nmat2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Tare R, Andar A, Riehle MO, Herzyk P, et al. The control of human mesenchymal cell differentiation using nanoscale symmetry and disorder. Nat Mater. 2007;6(12):997–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinton DA, Daley GQ. The promise of induced pluripotent stem cells in research and therapy. Nature. 2012;481(7381):295–305. doi: 10.1038/nature10761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Takebe T, Sekine K, Enomura M, Koike H, Kimura M, Ogaeri T, et al. Vascularized and functional human liver from an iPSC-derived organ bud transplant. Nature. 2013;499(7459):481–4. doi: 10.1038/nature12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sazia Sharmin AT, Kaku Yusuke, Yoshimura Yasuhiro, Ohmori Tomoko, Sakuma Tetsushi, Mukoyama Masashi, Yamamoto Takashi, Kurihara Hidetake, Nishinakamura Ryuichi. Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell–Derived Podocytes Mature into Vascularized Glomeruli upon Experimental Transplantation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2015010096. 2015/11/19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grskovic M, Javaherian A, Strulovici B, Daley GQ. Induced pluripotent stem cells — opportunities for disease modelling and drug discovery. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. 2011;10(12):915–29. doi: 10.1038/nrd3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leyton-Mange J, Milan D. Pluripotent Stem Cells as a Platform for Cardiac Arrhythmia Drug Screening. Curr Treat Options Cardio Med. 2014;16(9):1–18. doi: 10.1007/s11936-014-0334-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braam SR, Passier R, Mummery CL. Cardiomyocytes from human pluripotent stem cells in regenerative medicine and drug discovery. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 2009;30(10):536–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou P, Li Y, Zhang X, Liu C, Guan J, Li H, et al. Pluripotent Stem Cells Induced from Mouse Somatic Cells by Small-Molecule Compounds. Science. 2013;341(6146):651–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1239278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meregalli M, Farini A, Torrente Y. Stem cell therapy for neuromuscular diseases. INTECH Open Access Publisher; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu C, Inokuma MS, Denham J, Golds K, Kundu P, Gold JD, et al. Feeder-free growth of undifferentiated human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotech. 2001;19(10):971–4. doi: 10.1038/nbt1001-971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heiskanen A, Satomaa T, Tiitinen S, Laitinen A, Mannelin S, Impola U, et al. N-glycolylneuraminic acid xenoantigen contamination of human embryonic and mesenchymal stem cells is substantially reversible. Stem Cells. 2007;25(1):197–202. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin MJ, Muotri A, Gage F, Varki A. Human embryonic stem cells express an immunogenic nonhuman sialic acid. Nat Med. 2005;11(2):228–32. doi: 10.1038/nm1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim S, Ahn SE, Lee JH, Lim D-S, Kim K-S, Chung H-M, et al. A Novel Culture Technique for Human Embryonic Stem Cells Using Porous Membranes. STEM CELLS. 2007;25(10):2601–9. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodin S, Antonsson L, Niaudet C, Simonson OE, Salmela E, Hansson EM, et al. Clonal culturing of human embryonic stem cells on laminin-521/E-cadherin matrix in defined and xeno-free environment. Nat Commun. 2014:5. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim HT, Lee KI, Kim DW, Hwang DY. An ECM-based culture system for the generation and maintenance of xeno-free human iPS cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(4):1041–50. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin S, Yao H, Weber JL, Melkoumian ZK, Ye K. A Synthetic, Xeno-Free Peptide Surface for Expansion and Directed Differentiation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e50880. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melkoumian Z, Weber JL, Weber DM, Fadeev AG, Zhou Y, Dolley-Sonneville P, et al. Synthetic peptide-acrylate surfaces for long-term self-renewal and cardiomyocyte differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotech. 2010;28(6):606–10. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brafman DA, Chang CW, Fernandez A, Willert K, Varghese S, Chien S. Long-term human pluripotent stem cell self-renewal on synthetic polymer surfaces. Biomaterials. 2010;31(34):9135–44. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mei Y, Saha K, Bogatyrev SR, Yang J, Hook AL, Kalcioglu ZI, et al. Combinatorial development of biomaterials for clonal growth of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Mater. 2010;9(9):768–78. doi: 10.1038/nmat2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang -W, Hwang Y, Brafman D, Hagan T, Phung C, Varghese S. Engineering cell–material interfaces for long-term expansion of human pluripotent stem cells. Biomaterials. 2013;34(4):912–21. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villa-Diaz LG, Nandivada H, Ding J, Nogueira-de-Souza NC, Krebsbach PH, O'Shea KS, et al. Synthetic polymer coatings for long-term growth of human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotech. 2010;28(6):581–3. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Irwin EF, Gupta R, Dashti DC, Healy KE. Engineered polymer-media interfaces for the long-term self-renewal of human embryonic stem cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32(29):6912–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.05.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7(3):211–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sant S, Hancock MJ, Donnelly JP, Iyer D, Khademhosseini A. BIOMIMETIC GRADIENT HYDROGELS FOR TISSUE ENGINEERING. The Canadian journal of chemical engineering. 2010;88(6):899–911. doi: 10.1002/cjce.20411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kraehenbuehl TP, Langer R, Ferreira LS. Three-dimensional biomaterials for the study of human pluripotent stem cells. Nat Meth. 2011;8(9):731–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lei Y, Schaffer DV. A fully defined and scalable 3D culture system for human pluripotent stem cell expansion and differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(52):E5039–E48. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309408110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Otake K, Inomata H, Konno M, Saito S. Thermal analysis of the volume phase transition with N-isopropylacrylamide gels. Macromolecules. 1990;23(1):283–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Z-N, Xu Y. Progress and bottleneck in induced pluripotency. Cell Regeneration. 2012;1(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/2045-9769-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hong So G, Winkler T, Wu C, Guo V, Pittaluga S, Nicolae A, et al. Path to the Clinic: Assessment of iPSC-Based Cell Therapies In Vivo in a Nonhuman Primate Model. Cell Reports. 7(4):1298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kabra H, Hwang Y, Lim HL, Kar M, Arya G, Varghese S. Biomimetic Material-Assisted Delivery of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Derivatives for Enhanced In Vivo Survival and Engraftment. ACS Biomaterials Science & Engineering. 2015;1(1):7–12. doi: 10.1021/ab500021a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kar M, Vernon Shih Y-R, Velez DO, Cabrales P, Varghese S. Poly(ethylene glycol) hydrogels with cell cleavable groups for autonomous cell delivery. Biomaterials. 2016;77:186–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bensaïd W, Triffitt JT, Blanchat C, Oudina K, Sedel L, Petite H. A biodegradable fibrin scaffold for mesenchymal stem cell transplantation. Biomaterials. 2003;24(14):2497–502. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00618-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu SQ, Rachel Ee PL, Ke CY, Hedrick JL, Yang YY. Biodegradable poly(ethylene glycol)–peptide hydrogels with well-defined structure and properties for cell delivery. Biomaterials. 2009;30(8):1453–61. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mullen CA, Haugh MG, Schaffler MB, Majeska RJ, McNamara LM. Osteocyte differentiation is regulated by extracellular matrix stiffness and intercellular separation. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2013;28:183–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2013.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu Y, Goldberg AJ, Dennis JE, Gronowicz GA, Kuhn LT. One-Step Derivation of Mesenchymal Stem Cell (MSC)-Like Cells from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells on a Fibrillar Collagen Coating. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e33225. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou L, Luo Y, Chen M, Wang G, Ding M, Petersen CC, et al. A simple method for deriving functional MSCs and applied for osteogenesis in 3D scaffolds. Scientific reports. 2013;3:2243. doi: 10.1038/srep02243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bilousova G, Jun DH, King KB, De Langhe S, Chick WS, Torchia EC, et al. Osteoblasts derived from Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells form Calcified Structures in Scaffolds both in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells (Dayton, Ohio) 2011;29(2):206–16. doi: 10.1002/stem.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wei Y, Zeng W, Wan R, Wang J, Zhou Q, Qiu S, et al. Chondrogenic differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells from osteoarthritic chondrocytes in alginate matrix. European cells & materials. 2012;23:1–12. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v023a01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Levenberg S, Huang NF, Lavik E, Rogers AB, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Langer R. Differentiation of human embryonic stem cells on three-dimensional polymer scaffolds. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100(22):12741–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1735463100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bigdeli N, Karlsson C, Strehl R, Concaro S, Hyllner J, Lindahl A. Coculture of human embryonic stem cells and human articular chondrocytes results in significantly altered phenotype and improved chondrogenic differentiation. Stem Cells. 2009;27(8):1812–21. doi: 10.1002/stem.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jin G-Z, Kim T-H, Kim J-H, Won J-E, Yoo S-Y, Choi S-J, et al. Bone tissue engineering of induced pluripotent stem cells cultured with macrochanneled polymer scaffold. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 2013;101A(5):1283–91. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Peppo GM, Marcos-Campos I, Kahler DJ, Alsalman D, Shang L, Vunjak-Novakovic G, et al. Engineering bone tissue substitutes from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110(21):8680–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301190110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kang H, Shih Y-RV, Hwang Y, Wen C, Rao V, Seo T, et al. Mineralized gelatin methacrylate-based matrices induce osteogenic differentiation of human induced pluripotent stem cells. Acta Biomaterialia. 2014;10(12):4961–70. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kang H, Wen C, Hwang Y, Shih YR, Kar M, Seo SW, et al. Biomineralized matrix-assisted osteogenic differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Journal of materials chemistry B, Materials for biology and medicine. 2014;2(34):5676–88. doi: 10.1039/C4TB00714J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wen C, Kang H, Shih YV, Hwang Y, Varghese S. In vivo comparison of biomineralized scaffold-directed osteogenic differentiation of human embryonic and mesenchymal stem cells. Drug delivery and translational research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s13346-015-0242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang D, Shadrin IY, Lam J, Xian H-Q, Snodgrass HR, Bursac N. Tissue-engineered cardiac patch for advanced functional maturation of human ESC-derived cardiomyocytes. Biomaterials. 2013;34(23):5813–20. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turnbull IC, Karakikes I, Serrao GW, Backeris P, Lee J-J, Xie C, et al. Advancing functional engineered cardiac tissues toward a preclinical model of human myocardium. The FASEB Journal. 2014;28(2):644–54. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-228007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schaaf S, Shibamiya A, Mewe M, Eder A, Stöhr A, Hirt MN, et al. Human Engineered Heart Tissue as a Versatile Tool in Basic Research and Preclinical Toxicology. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e26397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen QZ, Ishii H, Thouas GA, Lyon AR, Wright JS, Blaker JJ, et al. An elastomeric patch derived from poly(glycerol sebacate) for delivery of embryonic stem cells to the heart. Biomaterials. 2010;31(14):3885–93. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tulloch NL, Muskheli V, Razumova MV, Korte FS, Regnier M, Hauch KD, et al. Growth of Engineered Human Myocardium With Mechanical Loading and Vascular Coculture. Circulation Research. 2011;109(1):47–59. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nunes SS, Miklas JW, Liu J, Aschar-Sobbi R, Xiao Y, Zhang B, et al. Biowire: a platform for maturation of human pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Nat Meth. 2013;10(8):781–7. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miklas JW, Nunes SS, Sofla A, Reis LA, Pahnke A, Xiao Y, et al. Bioreactor for modulation of cardiac microtissue phenotype by combined static stretch and electrical stimulation. Biofabrication. 2014;6(2):024113. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/6/2/024113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hirt MN, Boeddinghaus J, Mitchell A, Schaaf S, Börnchen C, Müller C, et al. Functional improvement and maturation of rat and human engineered heart tissue by chronic electrical stimulation. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2014;74:151–61. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lim HL, Chuang JC, Tran T, Aung A, Arya G, Varghese S. Dynamic Electromechanical Hydrogel Matrices for Stem Cell Culture. Advanced Functional Materials. 2011;21(1):55–63. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201001519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kannan RY, Salacinski HJ, Sales K, Butler P, Seifalian AM. The roles of tissue engineering and vascularisation in the development of micro-vascular networks: a review. Biomaterials. 2005;26(14):1857–75. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phadke A, Hwang Y, Kim SH, Kim SH, Yamaguchi T, Masuda K, et al. Effect of scaffold microarchitecture on osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. European cells & materials. 2013;25:114–28. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v025a08. discussion 28-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Druecke D, Langer S, Lamme E, Pieper J, Ugarkovic M, Steinau HU, et al. Neovascularization of poly(ether ester) block-copolymer scaffolds in vivo: long-term investigations using intravital fluorescent microscopy. Journal of biomedical materials research Part A. 2004;68(1):10–8. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.20016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cohen DL, Malone E, Lipson H, Bonassar LJ. Direct freeform fabrication of seeded hydrogels in arbitrary geometries. Tissue Eng. 2006;12(5):1325–35. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hutmacher DW, Sittinger M, Risbud MV. Scaffold-based tissue engineering: rationale for computer-aided design and solid free-form fabrication systems. Trends in Biotechnology. 2004;22(7):354–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zisch AH, Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Biopolymeric delivery matrices for angiogenic growth factors. Cardiovascular Pathology. 2003;12(6):295–310. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(03)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levenberg S, Rouwkema J, Macdonald M, Garfein ES, Kohane DS, Darland DC, et al. Engineering vascularized skeletal muscle tissue. Nat Biotech. 2005;23(7):879–84. doi: 10.1038/nbt1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chaturvedi RR, Stevens KR, Solorzano RD, Schwartz RE, Eyckmans J, Baranski JD, et al. Patterning vascular networks in vivo for tissue engineering applications. Tissue engineering Part C, Methods. 2015;21(5):509–17. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2014.0258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Culver JC, Hoffmann JC, Poché RA, Slater JH, West JL, Dickinson ME. Three-Dimensional Biomimetic Patterning in Hydrogels to Guide Cellular Organization. Advanced Materials. 2012;24(17):2344–8. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Miller JS. The Billion Cell Construct: Will Three-Dimensional Printing Get Us There? PLoS Biology. 2014;12(6):e1001882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miller JS, Stevens KR, Yang MT, Baker BM, Nguyen D-HT, Cohen DM, et al. Rapid casting of patterned vascular networks for perfusable engineered three-dimensional tissues. Nat Mater. 2012;11(9):768–74. doi: 10.1038/nmat3357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kolesky DB, Truby RL, Gladman AS, Busbee TA, Homan KA, Lewis JA. 3D Bioprinting of Vascularized, Heterogeneous Cell-Laden Tissue Constructs. Advanced Materials. 2014;26(19):3124–30. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.