Abstract

This review summarises the evidence for inequalities in community and consumer nutrition environments from ten previous review articles, and also assesses the evidence for the effect of the community and consumer nutrition environments on dietary intake. There is evidence for inequalities in food access in the US but trends are less apparent in other developed countries. There is a trend for greater access and availability to healthy and less healthy foods relating to better and poorer dietary outcomes respectively. Trends for price show that higher prices of healthy foods are associated with better dietary outcomes. More nuanced measures of the food environment, including multi-dimensional and individualised approaches, would enhance the state of the evidence and help inform future interventions.

Background

Socioeconomic disparities in dietary quality exist in developed countries across the globe (Ball et al. 2004;Ecob et al. 2000;Robinson et al. 2004) and are contributing to the inequitable distribution of conditions such as obesity and cardiovascular disease (Fox et al. 2011;McLaren 2007;Mente et al. 2009). Dietary intake is recognised as a complex behaviour of multi-factorial origin, whereby individual and environmental factors interact to influence what people eat (Foresight 2007;Story et al. 2008). Areas with little or no provision of healthy foods are believed to contribute to disparities in diet-related conditions such as obesity and diabetes, particularly in the United States (US) (Larson et al. 2009;Walker et al. 2010).

There is growing evidence that the neighbourhood food environment is an important determinant of dietary behaviour and obesity (Giskes et al. 2011;Holsten 2009;Lovasi et al. 2009) and an increasing consensus over the need to adapt the environment to make healthy choices easier, particularly for individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds (Department of Health UK 2010). Recent recommendations from the United Nations stressed the need for member states to provide equitable access and availability to foods that contribute to a healthy diet and discourage the production and promotion of foods that contribute to an unhealthy diet (United Nations General Assembly 2012).

The literature examining associations between neighbourhood environmental factors and socio-economic indicators or diet has grown in recent years (Caspi et al. 2012b). The neighbourhood food environment literature has tried to address many different research questions using a variety of different outcome and exposure measures and very few valid or reliable measures (Charreire et al. 2010;Gustafson et al. 2012;McKinnon et al. 2009b). This diversity in methodologies combined with the ecological design of the vast majority of studies has made interpreting this body of literature challenging within the standard systematic review paradigm.

As a result, previous reviews of the evidence have made recommendations for further research rather than concise conclusions about the strength or range of effect sizes of the current evidence base (Caspi, Sorensen, Subramanian, & Kawachi 2012b;Giskes, van Lenthe, Avendano-Pabon, & Brug 2011;Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010). This paper offers the first synthesis of previous review articles to determine the evidence for socioeconomic disparities in the neighbourhood food environment and explores the potential for quantifying the relationship between the food environment and dietary inequalities.

Organising the evidence

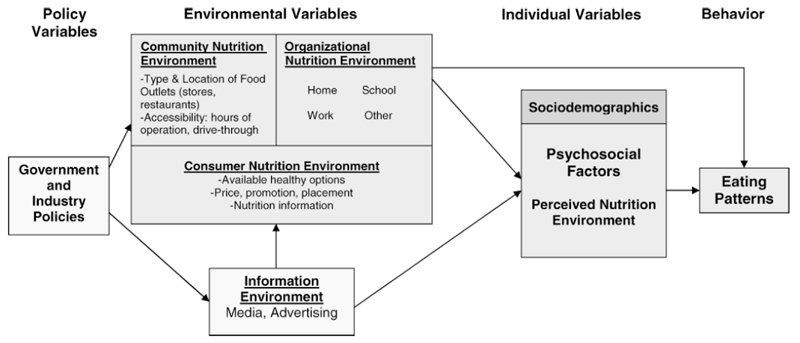

Leading academics in the food environment field have called for research to use conceptual models that theorise and test the mechanisms by which specific environmental exposures interact with individual factors to influence health behaviours such as diet (Cummins 2007;McKinnon et al. 2009a;Oakes et al. 2009). A widely used model of the food environment is that of Glanz et al in 2005 (Figure 1). It considers the policy, environmental, social and individual determinants of diet. The model links dietary behaviour directly to a collection of three settings: community nutrition environment, consumer nutrition environment and organisational nutrition environment. The model also suggests that the effect of these settings plus a fourth setting, the information environment (media and advertising), may be moderated or mediated by demographic, psychosocial or perceived environmental factors.

Figure 1.

Model of nutrition environments (Glanz et al. 2005)

Most of the food environment research to date has focused on the community nutrition environment (Caspi, Sorensen, Subramanian, & Kawachi 2012b;Thornton et al. 2010b) which measures the accessibility of food sources in the context of residential neighbourhoods. These studies use Geographic Information Systems (GIS) or other methods to determine the geospatial location of food sources to measure accessibility in terms of outlet proximity, density and to lesser extent diversity (Charreire, Casey, Salze, Simon, Chaix, Banos, Badariotti, Weber, & Oppert 2010;McKinnon, Reedy, Morrissette, Lytle, & Yaroch 2009b). Proximity assesses the minimum distance between food outlet and residence or proxy location, using road network, Euclidean distance or travel time. Density quantifies the availability of different types of food outlets within a specific area such as census tracts or buffer zones around centroid, home or food outlet. Density calculations may include total count, count per population, per square area or kernel density estimation (density calculation weighted by distance from origin). Diversity measures the different types of outlets for example the number of different fast food outlets.

The consumer nutrition environment reflects factors that consumers encounter within a retail food outlet such as the types of food available, price, promotions, placement, range of choice, freshness or quality and nutrition information. Assessment of the in-store environment typically requires internal audits by observation using a checklist or market basket tool (McKinnon, Reedy, Morrissette, Lytle, & Yaroch 2009b). A range of such tools have been developed where the majority measure product availability and price. A smaller number of tools consider additional factors such as product quality or variety (Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012). Fewer studies have explored consumer nutrition environment factors probably due to the time and financial costs associated with collecting and analysing such data (Thornton & Kavanagh 2010b).

The organisational nutrition environment refers to specific institutional settings where defined groups of people consume food such as workplace cafeterias or children’s centres, churches and healthcare facilities. The nutrition environment of these institutions has long been identified as an important determinant of health whereby the ethos, policies and practices of the setting can heavily influence an individual’s beliefs and behaviours including food choices (McLeroy et al. 1988). To date the role of organisational nutrition environments have rarely been considered in reviews of the food environment literature. However, these settings can play an important part of an individual’s day-to-day life and form part of their food environment exposure.

This paper uses the model by Glanz and colleagues to structure a review of the literature with a key focus on identifying the evidence for the role of the food environment on dietary inequalities. This review is restricted to research conducted in developed nations, on adults aged 18-60 years and does not cover literature on the organisational nutrition environment. More specifically, the review i) summarises the evidence for neighbourhood disparities in community and consumer nutrition environments from previous review articles, and ii) assesses the evidence for the effect on dietary intake.

Methods

In order to summarise the evidence for neighbourhood disparities in community and consumer nutrition environments previous semi-systematic and systematic review articles assessing this literature were identified and synthesised. A literature search for reviews was completed in January 2013 using Medline and Web of Science databases using the search terms ‘review’ and ‘food environment’. A total of 123 articles were reviewed. After screening and analysis a total of ten papers were found to have reviewed the findings of studies investigating neighbourhood disparities in the community and consumer nutrition environments. Review papers that described methods for assessing the food environment were excluded. Collectively these 10 review articles considered research on the community and consumer nutrition environment to early 2011. Additional original research papers recently published were also considered to present examples of more recent evidence.

To answer the second aim of the paper, and assess the evidence for an effect of the community and consumer nutrition environments on dietary intake, a literature search was performed in in November 2012 and again in September 2013 using Medline, Embase, AMED and PsycArticles, and Web of Science databases. Both MeSH and free terms were applied including ‘environmental medicine’ (MeSH), ‘food stores’, ‘food outlet’, ‘food price’, ‘food availability’, ‘food promotions’, ‘food habits’ (MeSH), ‘diet’, ‘consumption’ and ‘intake’. A total of 3943 articles were returned in November 2012. After screening abstracts and removing duplicates 59 original research articles and two review articles were identified. A further 33 articles were excluded because they did not assess the direct relationship between objective measures of permanent food outlets and dietary outcomes in adults aged 18-60 years. An additional 21 articles were identified from the bibliographies of relevant papers and through contact with experts in the field of food environment research. In September 2013 nine new studies that met the inclusion criteria were identified. Due to the heterogeneity of the exposure and outcome variables used in these original research papers a meta-analysis could not be performed. As an alternative, exposure measurements were tallied according to the direction of their relationship with three common dietary outcomes: dietary quality, fruit and vegetable intake or fast food intake. Several exposure measures from a single article may have been included in the count. Exposure measures were grouped by store type and key environmental variables (density, proximity, availability, price, quality and variety). The final results were presented in tables or graphs. Similar methods were used to summarise studies which investigated relationships between environmental variables and diet in disadvantaged populations.

Results

Question 1: Disparities in the neighbourhood food environment

A total of ten published reviews have assessed studies investigating differences in neighbourhood deprivation or ethnicity of the community nutrition environment and/or the consumer nutrition environment (Beaulac et al. 2009;Black et al. 2008;Fleischhacker et al. 2011;Ford et al. 2008;Fraser et al. 2010;Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012;Hilmers et al. 2012;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Lovasi, Hutson, Guerra, & Neckerman 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010). Three articles were described as systematic reviews (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Fleischhacker, Evenson, Rodriguez, & Ammerman 2011;Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012) however, only one review by Beaulac et al indicated that two independent authors had reviewed the search results. Collectively, these reviews consider 102 original research papers from five developed countries, which were published from 1966 to 2011. Four of the ten review articles assessed literature solely from the US where the bulk of the research in this field has been conducted (Ford & Dzewaltowski 2008;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Lovasi, Hutson, Guerra, & Neckerman 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010). The remaining six reviews took an international perspective but were limited to research from developed nations and papers published in English. Of the 102 papers reviewed, 70 were from the US, 12 from the UK, 11 from Canada, seven from Australia and two from New Zealand. Approximately half (47%) of the studies focused on assessing neighbourhood disparities in the community nutrition environment, 34% on the consumer nutrition environment and 19% included measures of both these nutrition environments. There was much overlap in original research papers reviewed, with 41% of studies featuring in more than one review article.

The reviews considered heterogeneity in measurements of the community and consumer nutrition environments to be a major challenge in interpreting the literature. A variety of definitions of neighbourhood and food outlets had been used and a range of analyses applied for measures of food outlet density or proximity and the availability and price of food within stores. As a result of this heterogeneity none of the review articles were able to perform a meta-analysis. A summary of the ten review articles is provided in Table 1 and a summary of their main findings are described below.

Table 1.

Summary of review articles and key findings relevant to neighbourhood inequalities in the community nutrition environment and consumer nutrition environment.

| Author, year | Review aim and methods | Number of papers reviewed | Geographical coverage | Key findings - Community nutrition environment | Key findings - Consumer nutrition environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Hilmers,

2012 Am J Public Health |

Examine socio-economic/ ethnic disparities in

neighbourhood access to fast food outlets and convenience

stores. Reviewed literature from 2000 to 2011. |

24 in total, all relevant to this

review. 14 ecological design. |

Australia Canada New Zealand UK US |

14 of 18 studies identified fast food access

favoured more deprived areas. 5 of 9 studies found fast food access was greater in predominantly ethnic areas. All 8 studies found higher density of convenience stores in areas of higher deprivation/ ethnicity. |

|

|

Gustafson,

2012 J Community Health |

Review literature on food availability in

stores and neighbourhood characteristics, diet, weight and food

prices. Reviewed literature between 2000 and 2011. Described as systematic review. |

56 in total. 30 relevant to this review, all cross-sectional design. |

Australia UK US |

Inconsistent evidence for less availability of

healthy food (6 of 10) and F&V (7 of 11) in poorer/ ethnic

areas. Prices of healthy foods (2 of 8) rarely differed by area deprivation. All 8 studies showed quality of healthy foods was poorer in more deprived areas. |

|

| Fleischhacker, 2010 Obesity Reviews |

Systematic review to examine the evidence on

fast food access and its associations with socioeconomic status,

ethnicity, obesity, other health

behaviours/outcomes. Reviewed literature between 1998 and 2008. Described as systematic review. |

40 in total. 17 relevant to this review. 3 cross-sectional design and 14 ecological design. |

Australia Canada New Zealand UK US |

Only 3 of 15 studies did not find fast food

outlets were more prevalent in low income areas (all

non-US). 7 of 9 studies found fast food outlets were more prevalent in high ethnic minority areas. |

|

|

Fraser,

2010 Int J Environ Research Public Health |

Summarise the literature regarding fast food

outlet location by area deprivation, dietary intake and

weight. Reviewed literature between 1990 and 2009. |

33 in total. 12 relevant to this review, all ecological design. |

Australia Canada New Zealand UK US |

10 out of 11 studies showed associations

between increasing area deprivation and access to fast food

outlets. The 2 studies identified showed a positive association between area ethnicity and access to fast food outlets. |

|

|

Walker,

2010 Health & Place |

To review the literature on healthy food

access in the US. Reviewed literature up to January 2010. |

31 in total. 20 relevant to this review. 8 cross-sectional design and 12 ecological design. |

US | Evidence to suggest that disparities in

supermarket access exist with ethnic minority and low-income

neighbourhoods being disproportionately

affected. Non-chain smaller grocery stores are more likely to be located in poor areas. Supermarkets are more prevalent in more affluent areas. |

Chain supermarkets have lower prices and

better availability and quality of healthy food than smaller non-chain

stores. Residents of neighbourhoods with no supermarket pay more for food and have poorer quality food. |

|

Beaulac,

2009 Preventing Chronic Disease |

To determine whether access to healthy,

affordable food in retails stores varies by area, specifically

disadvantaged areas. Reviewed literature up to 2007. Systematic review - two independent authors reviewed the search results. |

52 in total, all relevant to this

review. 32 cross-sectional design and 20 ecological design. |

Australia Canada New Zealand UK US |

18 out of 19 US studies showed low-income/

black American areas were underserved by grocery stores compared with

more advantaged areas. In other developed countries, 1 out of 6 studies found that low-income areas had poorer access to grocery stores while 2 studies showed low income areas had better access. |

5 of 9 US studies found poorer availability

and quality of foods in disadvantaged areas. 6 of 9 nine studies in other developed countries found no difference in availability, variety or quality of healthy foods by area deprivation. In all countries findings for price were mixed and complex. From a total of 23 studies, 3 found higher prices in poorer areas, 4 found lower prices in poorer areas and 16 found mixed or no association. |

|

Larson,

2009 Am J Prev Medicine |

To comprehensively review disparities across

the US according to neighbourhood access to more and less healthy foods

and obesity and dietary outcomes. Reviewed literature between 1985 and 2008. |

54 in total. 26 relevant to this review. 14 cross-sectional design and12 ecological design. |

US | 14 of 17 studies showed low income and ethnic

neighbourhoods were more often affected by poor access to supermarkets

than more affluent areas. 4 of 6 studies showed access to fast food outlets was greater in low income and minority areas. |

8 of 10 studies showed the availability of

healthy food was poorer in more disadvantaged areas. 2 of 2 studies showed restaurants in more affluent areas off more health menu options than low income areas. |

|

Lovasi,

2009 Epidemiologic Reviews |

To evaluate whether built environments might

explain ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in

obesity. Reviewed literature between 1995 and 2009. |

45 in total. 15 relevant to this review. 8 cross-sectional design and 7 ecological design. |

US | 10 of 15 studies found disadvantaged areas had

fewer supermarkets than more affluent areas. 5 of 8 studies found higher proportions of fast food outlets in more disadvantaged areas. |

|

|

Ford,

2008 Nutrition Reviews |

To provide preliminary evidence to assess: (a)

geographical disparities in the retail food environment, (b)

disadvantaged areas have poor-quality retail food environment (c)

individuals exposed to poor-quality retail food environments have poorer

quality diets and higher obesity rates. Reviewed literature from 1992 to 2007. |

13 in total, all relevant to this

review. 7 cross-sectional design and 6 ecological design. |

US | 8 of 9 studies found lower access to supermarkets in more deprived and ethnic areas compared to more affluent and white neighbourhoods. | 5 of 5 studies found poorer availability or

quality of healthy foods is more disadvantaged areas. 2 of 2 studies found no difference in price of products by area deprivation or ethnicity. |

| Black, 2007 Nutrition Reviews |

Comprehensively assess the neighbourhood

determinants of obesity in high-income

countries. Reviewed literature from 2005 to 2007. |

90 in total. 18 relevant to this review. 5 cross-sectional and 13 ecological. |

Australia Canada UK US |

9 US studies showed access to stores selling

healthy food is worse for low income neighbourhoods. 3 studies from Canada, Australia and UK did not identify differences in grocery store access by area deprivation. 2 studies found more food retailers in low income areas. 4 studies from the US, UK and Australia showed low income and ethnic neighbourhoods had greater exposure to fast food outlets. |

2 studies showed low income and ethnic areas had fewer healthy choices in local restaurants. |

Community nutrition environment

There is consensus across the nine articles reviewing the community nutrition environment of sufficient evidence that residents of low income or ethnic minority neighbourhoods in the US have disproportionally poorer access to healthy foods (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Black & Macinko 2008;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010) and greater access to food outlets selling less healthy foods (Black & Macinko 2008;Fleischhacker, Evenson, Rodriguez, & Ammerman 2011;Fraser, Edwards, Cade, & Clarke 2010;Hilmers, Hilmers, & Dave 2012;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009) than residents of more affluent neighbourhoods. One review concluded that the strongest evidence for environmental influences for socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in obesity is the unequal access to food stores (along with access to exercise facilities and neighbourhood safety (Lovasi, Hutson, Guerra, & Neckerman 2009). The evidence for differences in access to healthy food by level of area deprivation from other developed nations including Canada, Australia and the UK was equivocal (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Black & Macinko 2008). However, there was more consistent evidence for disparities in access to fast food outlets in these countries, with greater access in more deprived neighbourhoods (Black & Macinko 2008;Fleischhacker, Evenson, Rodriguez, & Ammerman 2011;Fraser, Edwards, Cade, & Clarke 2010;Hilmers, Hilmers, & Dave 2012).

The five review articles that assessed the evidence for neighbourhood differences in fast food access found that internationally, the vast majority of studies showed greater access to fast food outlets in neighbourhoods with higher levels of deprivation and minority populations (Black & Macinko 2008;Fleischhacker, Evenson, Rodriguez, & Ammerman 2011;Fraser, Edwards, Cade, & Clarke 2010;Hilmers, Hilmers, & Dave 2012;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009).

The United States

The four review articles which assessed the evidence for spatial disparities in grocery store access found consistent trends for low-income and ethnic communities in the United States having fewer supermarkets per capita and farther distances to travel to the closest store than more affluent communities (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Black & Macinko 2008;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010). For example, research assessing the national distribution of supermarkets by zip codes showed that residents in low income neighbourhoods had only 75% as many chain supermarkets as middle income neighbourhoods (Powell et al. 2007b). There were also differences in access according to ethnicity, with the availability of chain supermarkets in neighbourhoods with higher proportions of black residents roughly half that in predominantly white neighbourhoods. Similarly research from Detroit, which investigated distance to closest supermarket from census tracts centroid, showed the nearest supermarket was at a significantly greater distance from people’s homes in the most impoverished areas (>17% in poverty) compared with the least impoverished areas (<5% in poverty) (Zenk et al. 2005). Furthermore, the most impoverished black areas were 1.1 miles futher from the closest supermarket than the most impoverished white areas. A more recent study in a Texan county however, found that percent Latino in the neighbourhood was not associated with access to supermarkets, grocery stores or specialty stores but there was an association with exposure to convenience stores (Lisabeth et al. 2010). This brief summary suggests, as noted in the review by Black et al (Black & Macinko 2008), that there is evidence in the US that neighbourhood environmental factors may be inhibiting residents of more disadvantaged communities from making health dietary choices.

In the United States a national study that examined the distribution of food service outlets in more than 28,000 zip codes, found lower income neighbourhoods had 1.2 and 1.3 times the number of full service and fast food outlets of higher income neighbourhoods respectively (Powell et al. 2007a). These disparities were observed after adjustment for population density, urbanisation and region. Research from New York City highlights how black communities are disproportionally affected by fast food access with results showing that the prevalence of fast food outlets was positively associated with percentage of black residents (Kwate et al. 2009). This association was stronger than the association with median household income such that high income black neighbourhoods had similar exposure to fast food outlets as low income black neighbourhoods. A more recent study, included in one review article (Hilmers, Hilmers, & Dave 2012), applied a novel approach to assessing food outlet accessibility by creating an index that considered density of supermarkets, convenience stores selling healthy foods and fast food outlets in census blocks (Gordon et al. 2011). Results showed that predominantly black neighbourhoods had poorer food access scores while predominantly Latino and white neighbourhoods had better food access scores. Additionally, neighbourhoods with the highest median income had better food access scores compared with the lowest income neighbourhoods.

Other developed nations

Grocery store access studies from other developed nations including Australia, Canada and the UK have not consistently identified disparities in access to supermarkets and grocery stores among neighbourhoods of varied socioeconomic status (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Black & Macinko 2008) and very few studies have reported differences by the ethnic composition. For example, research from Melbourne, Australia, has shown that geographical access to supermarkets and fruit and vegetable stores was better for those living in more advantaged neighbourhoods (Ball et al. 2009). This finding was consistent across three measures of access: count within a two kilometre buffer of home, density per 10, 000 residents and closest proximity via road network. Another study from Melbourne, however, found that although more advantaged areas had closer access to supermarkets, most residents (>80%) lived within an 8-10 minute car journey of a major supermarket suggesting most people had good access to healthy food (Burns et al. 2007). Similarly, research in Brisbane, Australia, demonstrated no differences in shopping infrastructure according to the socioeconomic status of census districts (Winkler et al. 2006b). In Canada, research conducted in Edmonton revealed few differences in supermarket access across neighbourhoods of differing socioeconomic status or proportion of Aboriginal residents (Smoyer-Tomic et al. 2008). Furthermore, research in British Columbia and Quebec has shown that supermarkets pre-dominated low income neighbourhoods (Apparicio et al. 2007;Black et al. 2011), while in Ontario, lower income neighbourhoods were predominated by convenience stores (Latham et al. 2007). The evidence from the UK is also mixed. Assessment of the community nutrition environment in Wales and Northern England has shown poorer access to supermarkets in poorer areas (Clarke et al. 2002). Research in Glasgow, however, has shown little difference by neighbourhood deprivation (Macdonald et al. 2009) or better access to supermarkets in more deprived neighbourhoods (Cummins et al. 2002). Nation-wide research in Sweden, that was not included in the review articles, revealed that neighbourhoods of high deprivation have a greater prevalence of supermarkets and grocery stores than less deprived neighbourhoods (Kawakami et al. 2011). These results provide further indication that food access issues, which appear to be importance predictors of inequalities in the US, may be less apparent in other developed countries.

Socioeconomic trends in fast food access in other developed countries have been reasonably consistent with trends observed in the US (Black & Macinko 2008). Only three studies, from Canada and the UK, have shown no association between level of neighbourhood deprivation and fast food access (Fleischhacker, Evenson, Rodriguez, & Ammerman 2011;Fraser, Edwards, Cade, & Clarke 2010). In Australia for example, research in Melbourne has shown, that residents of the poorest neighbourhoods lived closer, and had up to 2.5 times more exposure to fast food outlets, than people living in wealthier neighbourhoods (Burns & Inglis 2007;Reidpath et al. 2002). In Edmonton, Canada, poorer neighbourhoods, as well as those with higher percentages of Aboriginal residents, had greater access to fast food outlets than more affluent neighbourhoods (Smoyer-Tomic, Spence, Raine, Amrhein, Cameron, Yasenovskiy, Cutumisu, Hemphill, & Healy 2008). This association remained after adjusting for supermarket proximity to residents’ homes. Research from the UK has shown a positive linear relationship between the density per 1000 population of McDonald’s and other chain fast food outlets and neighbourhood deprivation such that fast food outlets were more prevalent in poorer areas (Cummins et al. 2005b;Macdonald et al. 2007). However, investigations including all out-of-home eating outlets in Glasgow showed the density was highest in neighbourhoods of the second most affluent quintile (Macintyre et al. 2005). A recent study assessing facilities across Sweden revealed results consistent with the international trend showing higher prevalence of fast food outlets in more deprived neighbourhoods (Kawakami, Winkleby, Skog, Szulkin, & Sundquist 2011).

Consumer nutrition environment

Six review articles appraised neighbourhood disparities in the consumer nutrition environment literature, three with an international perspective (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Black & Macinko 2008;Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012) and three focused on literature from the US (Ford & Dzewaltowski 2008;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010). Ford et al (Ford & Dzewaltowski 2008) concluded that consumer nutrition environment studies revealed weaker associations between in-store variables and area deprivation than community nutrition environment studies that used store type as a proxy for healthy food (larger stores having greater availability and cheaper prices). However, the authors also stated that consumer nutrition environment studies are important because they allow for critical differences in availability, price and quality to be observed (Ford & Dzewaltowski 2008).

The United States

There is some evidence for neighbourhood disparities in the availability of healthier foods in the United States but the evidence for price is less robust (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Ford & Dzewaltowski 2008;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010). For example, results from in-store surveys in two socioeconomic and ethnically contrasting cities in Alabama revealed that the more disadvantaged city had a dominance of convenience stores which stocked few healthy foods. The more affluent city had no convenience stores and several chain supermarkets which offered a large variety of healthy food options and lower price ranges for some fruit and vegetables (Bovell-Benjamin et al. 2009). In contrast, survey results from grocery stores in two socio-economically and ethnically contrasting cities in Chicago showed that store prices were cheaper in the poorer community (Block et al. 2006).

Other developed countries

In other developed countries the evidence is equivocal (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012). In Australia, research in Brisbane showed no differences in fruit and vegetable price or availability by level of neighbourhood deprivation (Winkler et al. 2006a). In-store surveys in Melbourne however, revealed that fruit and vegetable availability slightly favoured more affluent neighbourhoods but food prices were cheaper in more deprived neighbourhoods (Ball, Timperio, & Crawford 2009). Cheaper food prices in poorer areas have also been observed in Canada (Latham & Moffat 2007) and the UK (Cummins & Macintyre 2002;Cummins et al. 2010).

Although limited and reviewed in only one article, evidence has consistently shown poorer quality produce in more deprived neighbourhoods (Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012). A recent study from the UK revealed that residents of the most deprived neighbourhoods had 69-76% greater risk of poor quality fruit and vegetables than residents of more affluent neighbourhoods (Black et al. 2012). The small body of evidence assessing the consumer nutrition environment in food service outlets, reviewed in only one article, revealed that restaurants in more affluent areas offer more healthy menu options than low income areas (Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009). The current evidence for socioeconomic neighbourhood differences in the consumer nutrition environment suggests that the relationship between the availability and price of healthy food and area deprivation is complex and context dependent (Ford & Dzewaltowski 2008). Variations in the foods assessed in stores and exclusion of in-store factors such as marketing and product placement limits the ability of the current body of evidence to determine whether neighbourhood differences in the consumer nutrition environment contribute to dietary inequalities (Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012).

Question 2: The neighbourhood food environment and dietary quality

In the search for evidence of a relationship between the community and consumer nutrition environments and dietary outcomes two systematic reviews were identified. Caspi et al (Caspi, Sorensen, Subramanian, & Kawachi 2012b) completed a systematic review of articles published prior to March 2011 which investigated a relationship between neighbourhood food environment exposures and diet. A total of 38 empirical studies were identified, 26 of which measured the relationship between objective community or consumer nutrition environment exposures and dietary outcomes in adults aged 18-60 years. More than two-thirds of the articles (n=26) used geographical exposure data to measure community nutrition environment against dietary outcomes. Gustafson et al (Gustafson, Hankins, & Jilcott 2012) systematically reviewed literature investigating the consumer nutrition environment of food stores from 2000 to 2011. A total of six articles that assessed the relationship between objective consumer nutrition environment exposures and diet in adults aged 18-60 years were identified. One article (Hermstad et al. 2010) was additional those identified by Caspi et al, however, has not been included in our review because multiple community and consumer nutrition environment variables were combined in a model, making direct comparison with other original research papers not possible.

The literature search for the present paper identified a further 27 articles (Ball et al. 2006;Boone-Heinonen et al. 2011;Burgoine et al. 2009;Burgoine et al. 2011;Casagrande et al. 2011;Caspi et al. 2012a;Duffey et al. 2010;Dunn et al. 2012;Fuller et al. 2013;Gordon-Larsen et al. 2011;Gustafson et al. 2013a;Gustafson et al. 2013b;Hickson et al. 2011;Jack et al. 2013;Layte et al. 2011;Macdonald et al. 2011;Minaker et al. 2013;Monsivais et al. 2012;Murakami et al. 2010;Ollberding et al. 2012;Rehm et al. 2011;Richardson et al. 2011;Robinson et al. 2013;Sadler et al. 2013;Sharkey et al. 2011;Thornton et al. 2012;White et al. 2004) in addition to those identified by Caspi et al and Gustafson et al. Grey literature identified from the bibliographies of relevant papers were included in this review however the grey literature was not systematically reviewed. All identified literature was reviewed by only one reviewer. The findings from the two systematic reviews and a summary of the original research papers investigating the neighbourhood food environment and dietary outcomes is provided below for the community and consumer nutrition environments respectively.

Community nutrition environment and dietary quality

A total of 31 articles, involving adults aged 18-60 years, measured access to food stores using measures of density. These studies tested whether (a) increased access to food stores selling healthy foods such as supermarkets/ greengrocers is associated with better dietary outcomes and/or (b) increased access to outlets selling less healthy foods like fast food outlets is associated with poorer dietary outcomes. The majority of these studies (n=20) identified at least one significant association between geographical density and their diet in the expected direction. Two studies assessed the ratio of number of healthy food outlets to less healthy food outlets (Retail Food Environment Index) within a specified boundary but found no association between overall retail exposure and diet(Gustafson, Christian, Lewis, Moore, & Jilcott 2013a;Minaker, Raine, Wild, Nykiforuk, Thompson, & Frank 2013). A total of 24 articles, involving adults aged 18-60 years, examined distance to nearest food outlet from participant’s home or proxy location. Thirteen of these papers revealed no association between proximity and diet. One study investigated fast food chain diversity and showed that increased numbers of different fast food outlets were linked with higher fast food intake (Thornton et al. 2009).

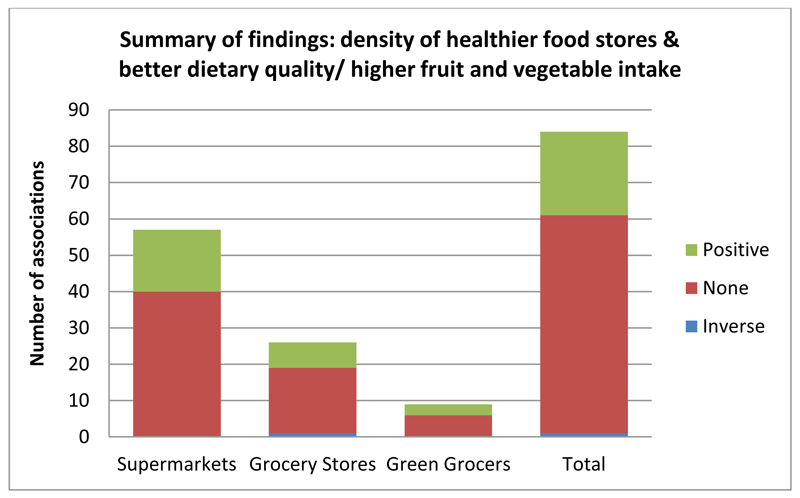

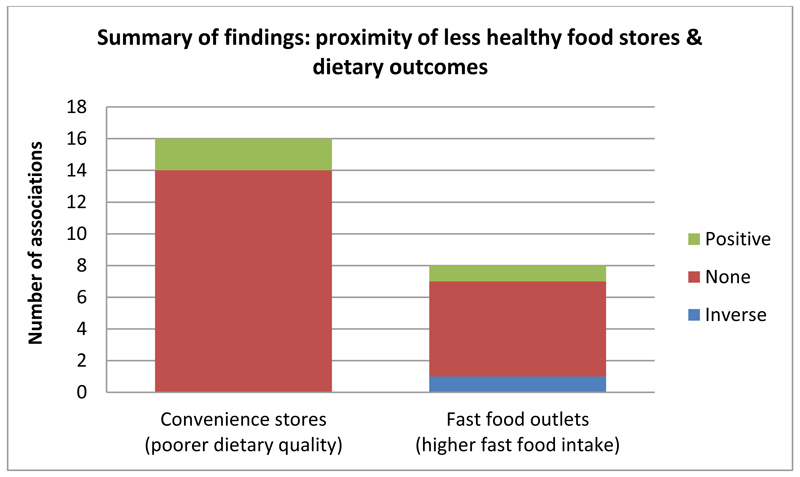

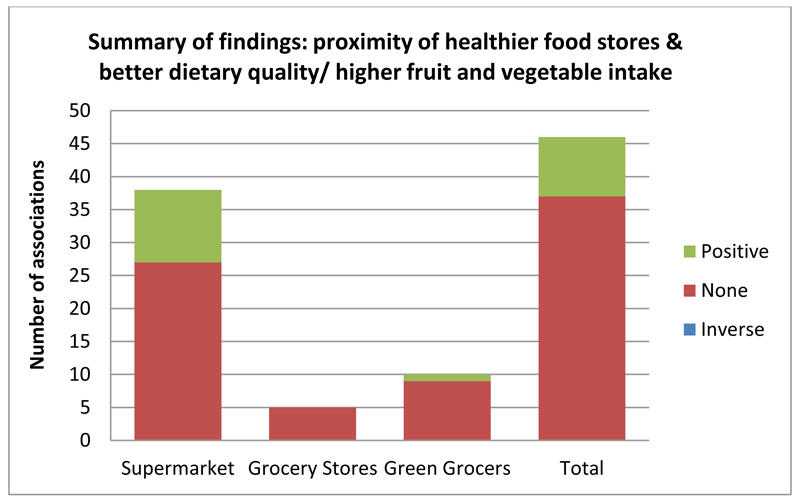

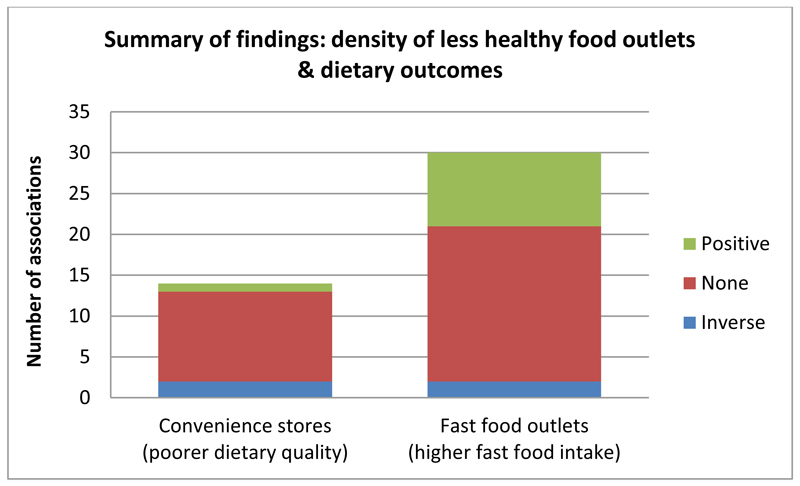

Summaries of the findings from the 42 original research papers investigating a relationship between community nutrition environment exposures and diet are presented in Figures 2-5. Around a quarter of the density findings provide evidence for expected associations: food stores selling healthy foods (supermarkets, grocery stores and green grocers) related to better dietary outcomes (27%) and less healthy food stores related to poorer dietary outcomes (22%). Approximately one fifth of the proximity findings provide for an association between healthier food stores and better dietary outcomes (20%) and even fewer indicate an association between less healthy food outlets and poorer dietary outcomes (13%). Very similar trends were observed in the few studies (n=9) that focused analyses on disadvantaged populations. More than a quarter of the density findings showed an association between density of healthier food stores and better dietary outcomes while, nearly a fifth showed evidence of an association between closer proximity to healthier food stores and better dietary outcomes. No relationships were observed between proximity of convenience stores and diet in disadvantaged populations however, proximity to fast food outlets was associated with higher fast food intake in the one study identified (Dunn, Sharkey, & Horel 2012). The evidence for the community nutrition environment shows a trend toward expected associations however the majority of findings reported no association. There is some variation by global regions which is discussed further below.

Figure 2.

Summary of findings relating density of healthier food stores to better dietary quality or higher fruit and vegetable intake.

* Across 42 different exposure measures, 17 studies and 21 papers.

Figure 5.

Summary of findings relating density of less healthy stores to poorer dietary outcomes.

* Across 5 different exposure measures for convenience stores, 7 studies and 7 papers.

* Across 1 different exposure measures for fast food outlets, 4 studies and 5 papers.

* 1 study was not included in the convenience store calculation because different outcome measures were used.

* 1 study was not included in the fast food outlet calculation because different outcome measures were used.

The United States

The majority of studies have been conducted in United States (n=24). This literature provides the strongest evidence of all regions for a relationship between community nutrition environment exposures and dietary outcomes with almost two thirds showing significant associations (p<0.05) in the expected direction. Better access to supermarkets and green grocers was associated with healthier dietary behaviours in ten studies. However, a further eleven studies revealed no significant associations. Two studies revealed negative associations between fruit and vegetable intake and the density of small grocery stores and convenience stores which are known to offer poorer availability of healthy foods (Gustafson et al. 2011;Powell et al. 2009). For example, Powell et al (Powell, Zhao, & Wang 2009) showed that each additional grocery store per 10,000 capita was associated with an approximate 3% decrease in weekly fruit and vegetable consumption (p=0.05). This study by Powell et al also showed that each additional fast food outlet per 10,000 capita was associated with an approximate 5% decrease in fruit and vegetable consumption. However, the evidence for a relationship between fast food access and fast food intake in the US is mixed with four of the nine studies showing mixed results and three returning null or unexpected findings. Results from a longitudinal study stratifying the sample by gender found no association between fast food outlet density and fast food consumption in women. For males however, 1% increase in access to fast food outlets within a 1km and 1-3km radius from home corresponded with modest increases in monthly fast food intake of 0.13% and 0.34% respectively (Boone-Heinonen, Gordon-Larsen, Kiefe, Shikany, Lewis, & Popkin 2011). The evidence suggests that while some inconsistency exists in the literature there is weak evidence for a relationship between community nutrition environment exposures and dietary outcomes in the US.

Canada

One comprehensive study in Ontario, Canada, has assessed the relationship between food access and diet (Minaker, Raine, Wild, Nykiforuk, Thompson, & Frank 2013). This study measured multiple aspects of the community nutrition environment including road network distance to nearest grocery store, convenience store and fast food outlet, total store and restaurant density within one kilometre of home, and the ratio of healthy to unhealthy stores and restaurants. Analyses were stratified by gender and results revealed not one significant relationship. These lack of findings suggest that in Canada, diet quality is not influenced by access to food stores and restaurants however, clear conclusions cannot be drawn from a single study.

Australasia

A total of eight articles were identified from the Australasia region: four from Australia, two from New Zealand and two from Japan. The outcomes from these papers are largely equivocal, with several studies revealing mixed results. For example, the SESAW study from Australia found that density of supermarkets per 10,000 residents (Ball, Crawford, & Mishra 2006) and within 2km radius of low-income women’s homes (Williams et al. 2010) was not associated with fruit and vegetable consumption. Higher supermarket density within 3 km radius of residence, however, was associated with increased vegetable consumption of the full sample of women (Thornton et al. 2010a). In New Zealand, research by Pearce et al (Pearce et al. 2008;Pearce et al. 2009) found no association between supermarket access and fruit and vegetable consumption. However, this study did show that residents with the worst access to fast food outlets were up to 17% more likely to consume the recommended intake of vegetables and those with the best access to convenience stores were up to 25% less likely to.

Europe

Across Europe, a total of nine articles written in English were identified: eight from the UK (5 in England and three in Scotland), and one from Ireland. This literature revealed many inconsistencies with several studies reporting inconsistent findings. In the UK, Burgoine et al (Burgoine, Alvanides, & Lake 2011) showed no association between fruit and vegetable consumption and density of supermarkets or convenience stores. They also found an unexpected association between elevated vegetable consumption and higher density of food service outlets. These outlets included restaurants as well as take-away outlets and the authors postulate that residents may not always be making unhealthy choices if they are eating-out within their neighbourhood. Two natural experiments exploring the effects of opening a new supermarket have been conducted in the UK. In northern England, consumers who switched supermarkets or lived within 500 meters of the new store had increased fruit and vegetable consumption after the new supermarket had opened (Wrigley et al. 2003). In Glasgow, however, no positive effect on the fruit and vegetable intake of neighbourhood residents was identified even though 30% of the sample reported switching to the new supermarket (Cummins et al. 2005a). The single non-UK study revealed a weak effect for supermarket access on dietary quality in the republic of Ireland: each additional supermarket within a two kilometre radius from home was associated with a 2.5% increase in diet score which represented a healthier dietary pattern (Layte, Harrington, Sexton, Perry, Cullinan, & Lyons 2011). The findings from studies in Europe demonstrate inconsistencies in the relationships between the community nutrition environment and diet and the effect sizes observed have been relatively small. However, the body of literature is limited, particularly outside the UK, and there is a need to improve methodological techniques to enhance the quality of this body of evidence (Caspi, Sorensen, Subramanian, & Kawachi 2012b;Charreire, Casey, Salze, Simon, Chaix, Banos, Badariotti, Weber, & Oppert 2010).

Consumer nutrition environment and dietary quality

A total of 20 studies used in-store audit tools to measure consumer nutrition environment exposures and dietary outcomes in adults aged 18-60 years. These studies tested whether (a) better availability, variety and quality of healthy foods is associated with healthier dietary intakes and/or (b) lower costs of healthy food and higher costs of less healthy food are associated with healthier dietary outcomes.

Different in-store audit tools were used across most studies and few studies reported the psychometric properties of reliability. Ten assessed product availability, six of which identified at least one positive association with diet. The eight studies that assessed price found either null associations or unexpected associations where better dietary patterns were associated with higher prices. The two longitudinal studies (Duffey, Gordon-Larsen, Shikany, Guilkey, Jacobs, Jr., & Popkin 2010;Gordon-Larsen, Guilkey, & Popkin 2011), however, showed that price increases on less healthy foods were associated with lower energy or fast food intake. Few studies measured the variety or quality of products (n=4) and results were mixed.

Summaries of the findings from the 20 original research papers investigating a relationship between consumer nutrition environment exposures and diet are presented in Table 2. Almost a quarter (24%) of findings regarding the availability of healthy products revealed that better availability was associated to better dietary outcomes. Findings for price investigations showed that while a fifth of studies showed that lower prices of healthy and less healthy products increased consumption of these foods, almost half of the findings regarding price showed that higher prices of healthy foods were associated with better dietary outcomes. Few studies (n=5) investigated the effect of produce variety or quality on dietary outcomes and the evidence is currently equivocal.

Table 2.

Summary of findings relating consumer nutrition environment exposures to better dietary quality/higher fruit and vegetable intake.

| Direction of relationship | Number of findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | Price | Variety | Quality | |

| Inverse (unexpected) | 2 | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| None | 27 | 12 | 3 | 4 |

| Positive | 9 | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of exposure measures | 20 | 13 | 3 | 4 |

| Number of papers | 11 | 10 | 3 | 4 |

| Number of studies | 11 | 10 | 3 | 4 |

The United States

A total of 16 studies from the United States have investigated links between factors within food stores and dietary outcomes. This region has the largest body of research on this topic and provides moderate evidence to support the hypothesis that the consumer nutrition environment influences diet. Of the ten studies investigating the relationship between product availability and dietary outcomes, six showed at least one significant association in the expected direction, healthy food availability and healthier dietary intakes. One study found that, after adjusting for individual characteristics, lower availability of healthy foods in residential neighbourhood was associated with higher scores on the poorer dietary pattern but not the better dietary pattern (Franco et al. 2009). Four studies using the NEMS-S market basket tool showed mixed results: lower availability of healthier foods was associated with poorer quality of diet patterns (Franco, Diez-Roux, Nettleton, Lazo, Brancati, Caballero, Glass, & Moore 2009) and better availability of healthier foods was associated with higher odds of eating at least one serve of vegetables a day (Gustafson, Lewis, Perkins, Wilson, Buckner, & Vail 2013b), but associations between higher dietary quality and lower availability of healthier foods have also been found (Casagrande, Franco, Gittelsohn, Zonderman, Evans, Fanelli, & Gary-Webb 2011).

Five of the nine studies investigating the effect of price on dietary outcomes found at least one significant association in the expected direction, higher prices and lower intake of less healthy items or lower prices and increased intakes of healthy items. A longitudinal price study showed a strong relationship between weekly fast food consumption and prices of soda and weaker associations for take-away burger prices (Gordon-Larsen, Guilkey, & Popkin 2011). This relationship was differentiated by ethnicity and income. The strongest association, in black males, showed a 20% increase in the price of soda was associated with a 0.25 reduction in number of days eating fast food per week. Two recent cross-sectional studies using published price data revealed negative associations between total diet cost and dietary quality such that better quality diets were more costly (Rehm, Monsivais, & Drewnowski 2011) and diet cost mediated the relationship between socioeconomic position and diet quality (Monsivais, Aggarwal, & Drewnowski 2012).

Other developed nations

Four studies have investigated product availability or price and diet outside of the US: two from the UK and one each from Canada and Australia. This small body of literature revealed inconsistent findings that can largely be considered inconclusive.

Discussion

This review has summarised the evidence for neighbourhood disparities in community and consumer nutrition environments from ten previous review articles, and also assessed the evidence for the effect of community and consumer nutrition environments on dietary intake. There is evidence that disadvantaged neighbourhoods in the US have poorer access to healthy foods than more affluent areas. Globally there is also a trend for greater access to less healthy foods in neighbourhoods of higher deprivation. More than a quarter of density investigations and a fifth of proximity investigations provide evidence for an association between increased access to stores selling healthy foods and better dietary outcomes. There is some evidence for neighbourhood disparities in the availability of healthier foods but the evidence on price is less robust. A quarter of the food availability investigations showed that greater availability of healthy foods was related to better dietary outcomes however, half of the price investigations revealed that higher prices for healthy products related to better dietary outcomes. The literature for other consumer nutrition environment factors such as variety, quality, placement and promotions is limited.

Community nutrition environment

There is consensus across review articles of evidence in the community nutrition environment literature for area-based inequalities in healthy food access in the US: residents of low income and ethnic minority neighbourhoods in the US have disproportionately poorer access to healthy food than residents of more affluent neighbourhoods. The evidence for differences in access to healthy food is equivocal for Australia, Canada and the UK. However, there is compelling international evidence for inequalities in access to less healthy foods: neighbourhoods with higher levels of deprivation and ethnic populations have greater access to fast food outlets than more affluent, predominantly white neighbourhoods. This evidence confirms that, particularly in the US, there is variation in terms of neighbourhood factors that influence diet and health. The stronger evidence from the US may be in-part due to the higher levels of urban residential segregation in the US than in other developed countries. Globally, low income areas offer low rent, low competition and cheap labour opportunities, however black areas in the US are also stigmatised and seen as undesirable to many retailers including supermarket chains (Kwate 2008). In these circumstances, policy makers may be reliant on retailers willing to trade in these communities such as fast food chains, to create jobs and employment opportunities for local residents.

Fraser et al (Fraser, Edwards, Cade, & Clarke 2010) have suggested that the disparities identified above are an illustration of the ‘deprivation amplification’ effect. Deprivation amplification describes how individual or household deprivation, for example low income or educational attainment, is amplified by area level deprivation and the conditions within deprived neighbourhoods such as the increased availability of less healthy foods or decreased availability of affordable healthy food (Macintyre et al. 1993). However, as has been suggested in the literature (Macintyre 2007) and confirmed by the evidence in our review, it may not always be true that poorer neighbourhoods provide a less healthful environment for residents. Two recent intervention studies, focused on mobile food stores, aimed to improve access to fruit and vegetables in low income communities. The interventions, which involved a mobile food store in the UK and farmers market in the US, found that self-reported intakes of fruit and vegetables had increased over the time period of the interventions (Evans et al. 2012;Jennings et al. 2012). Neither of these studies, however, used a control group or indicated adjustment for individual or societal factors that may have also influenced dietary intake. Other initiatives such as public-private partnerships to introduce supermarkets to underserved areas, improved transportation in low income neighbourhoods or restrictions and incentives for food retailers such as zoning regulations or tax rebates have been proposed as strategies to enable a more equitable distribution of food sources (Hilmers, Hilmers, & Dave 2012).

Consumer nutrition environment

There have been fewer studies of the consumer nutrition environment than the community nutrition environment and the findings of these studies are mixed. There is some evidence in the US for poorer availability of healthy products in low income and ethnic neighbourhoods than more affluent neighbourhoods. The evidence from other developed countries is weaker and less consistent. The evidence for neighbourhood disparities in price is varied across all countries with findings showing both cheaper and dearer prices in disadvantaged neighbourhoods. While few studies have assessed neighbourhood differences in quality of food, the evidence consistently showed poorer quality produce in more deprived than more affluent neighbourhoods. Moving to consider how consumer nutrition environment factors relate to diet, the literature shows evidence for associations between price and availability and dietary intake in the US. The literature and evidence from other developed countries is limited and weaker. Changes in the price of less healthy foods, particularly sweet carbonated drinks, have shown that as price increased intake of these foods decreased. This relationship was differentiated by ethnicity and income with the strongest associations observed in blacks and low-income earners. Local availability of healthy foods was also shown to relate to poorer dietary patterns but not better dietary patterns. This finding suggests that individuals with poorer diets may be disproportionately affected by their neighbourhood food environment than individuals with better quality diets. This disparity may result from being less likely to have access to a private car to travel to other shopping opportunities or more likely to keep daily activities to a more localised space (Coveney et al. 2009).

Limitations of the food environment literature

Methodological limitations of the neighbourhood food environment literature have been repeatedly cited in review articles (Beaulac, Kristjansson, & Cummins 2009;Black & Macinko 2008;Fleischhacker, Evenson, Rodriguez, & Ammerman 2011;Ford & Dzewaltowski 2008;Fraser, Edwards, Cade, & Clarke 2010;Larson, Story, & Nelson 2009;Walker, Keane, & Burke 2010). Heterogeneity in the categorisation of outlets, definition of neighbourhood and measurement of exposure variables, as well as the ecological study design of many studies have been reported as potential contributors to the inconsistent findings observed in review papers. A great assortment of neighbourhood boundaries have been applied including various predefined boundaries from census blocks to county boundaries and wide range of buffer zone radii measured by road network or Euclidean distance. A variety of food outlet categorisation systems have been applied across studies and the majority of studies have focused on one or two outlet types with very few assessing the neighbourhood differences or dietary affects of a full range of food retailers.

Much of the research to date is ecological in design, comparing neighbourhood or dietary data from national or cohort surveys with secondary food outlet information and may not accurately represent true associations. Few studies ground-truthed their food outlet data and may misrepresent food outlet access by including outlets that have ceased to trade and miss those which have recently opened. Field validation studies of secondary data have shown only fair to moderate agreement between observation and existence of food outlets from commercial and government lists or remote sensing technology such as Google street view (Lake et al. 2010;Powell et al. 2011). Levels of agreement, however, were poorer when categorisation of outlets was included in the comparison (Clarke et al. 2010;Rossen et al. 2012). The findings from secondary data may therefore need to be viewed with caution and more longitudinal studies are needed, particularly using individualised data.

Another methodological limitation of this body of literature is the premise that people shop and are primarily influenced by food outlets geographically proximate to their homes (Zenk et al. 2011). The assessment of individualised living spaces for community nutrition environment research has been piloted in two studies: one used seven day global positioning system tracking data to create a total individualised area by buffering all locations visited by 0.5 mile radius (Zenk, Schulz, Matthews, Odoms-Young, Wilbur, Wegrzyn, Gibbs, Braunschweig, & Stokes 2011) and the other used one day travel surveys and locations visited as anchor points to calculate an individualised area (Kestens et al. 2010). Time-geographic accessibility measures may also provide opportunities for more complete and realistic representations of the food environment by considering exposures along routes people regularly travel in conjunction with practical time restrictions on food shopping (Widener et al. 2013). Applying these individualised food environment exposure measures to individualised dietary measures will help eliminate the ambiguity found in the current evidence.

There is also a need for consumer nutrition environment studies to link dietary data to the in-store environment of where people shop to overcome previous methodological assumptions (Caspi, Sorensen, Subramanian, & Kawachi 2012b). Thus, consumer nutrition environment studies could be further enhanced by the use of reliable tools that assess the range of environmental stimuli consumers face when shopping in additional to product availability and price, including product placement, prominence, promotion and labelling (Kelly et al. 2011). These tools may also be useful for assessing organisational nutrition environments such as workplace canteens (Kelly, Flood, & Yeatman 2011).

It has been suggested that the single most important strategy for future food environment research is combining multiple environment assessment techniques. An intelligent mix of in-store audit measures and GIS based methods would provide a more accurate characterisation of the neighbourhood food environment (Rose et al. 2010). A good example of such multi-dimensional assessment is work by Hermstad et al (Hermstad, Swan, Kegler, Barnette, & Glanz 2010) which used structural equation modelling to investigate the relative influence of environmental, social and individual level factors on dietary fat intake. The reliable in-store audit tool NEMS-S was used to assess the availability, cost and quality of lower fat items and scores were summed for all grocery and convenience stores within a five mile radius of participants home. Proximity measures of fast food outlets were also calculated. Modelling calculations measured the combined effect of these exposures as well as the home nutrition environment, perceived nutrition environment and psychosocial factors. Further research applying a multi-dimensional approach to investigating the neighbourhood food environment and incorporating potential mediating factors such as transport method and psychosocial factors is needed. Recent qualitative research has also shown that residents of deprived neighbourhoods do not respond in a uniform manner to similar in-store supermarket environments suggesting a mediating role for psychosocial factors (Thompson et al. 2013). Therefore, socio-ecological conceptual approaches and sophisticated modelling techniques are required alongside qualitative research to enhance the current state of the evidence and identify the relative influence of multiple dimensions of the neighbourhood food environment and psychosocial factors on dietary inequalities. Findings of such research are likely to help inform the allocation of resources and development of complex interventions to improve disparities in dietary intake.

Conclusion

This review summarised the evidence for neighbourhood disparities in community and consumer nutrition environments from 10 previous review articles, and also assessed the evidence for an effect of the community and consumer nutrition environments on dietary intake. There is evidence for inequalities in food access in the US; trends are less evident in other developed countries. The evidence also shows a trend for greater access and availability, to either healthy or less healthy foods, relating to diet as expected. However unexpectedly, the evidence for price shows a trend for higher prices of healthy foods being associated with better dietary outcomes. The neighbourhood food environment literature suffers from considerable heterogeneity in methodology and generalised environmental exposures. These methodological limitations hinder the development of clear policy recommendations and interventions to improve nutrition environments. Further research applying a multi-dimensional approach and individualised environmental exposures is needed to enhance the current state of the evidence and help inform future interventions.

Figure 3.

Summary of findings relating proximity of healthier food stores to better dietary quality/fruit and vegetable intake.

* Across 11 different exposure measures, 16 studies and 18 papers.

Figure 4.

Summary of findings relating density of less healthy food stores to poorer dietary outcome.

* Across 10 different exposure measures for convenience stores, 7 studies and 7 papers.

* Across 12 different exposure measures for fast food outlets, 8 studies and 9 papers.

* 2 studies were not included in the convenience store calculation because different outcome measures were used.

* 5 studies were not included in the fast food outlet calculation because different outcome measures were used.

Acknowledgments

This review is independent research arising from a Doctoral Research Fellowship supported by the National Institute for Health Research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research or the Department of Health.

References

- Apparicio P, Cloutier MS, Shearmur R. The case of Montreal’s missing food deserts: Evaluation of accessibility to food supermarkets. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2007;6 doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-6-4. available from: ISI:000258119300001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Crawford D, Mishra G. Socio-economic inequalities in women’s fruit and vegetable intakes: a multilevel study of individual, social and environmental mediators. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(5):623–630. doi: 10.1079/phn2005897. available from: PM:16923294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Mishra GD, Thane CW, Hodge A. How well do Australian women comply with dietary guidelines? Public Health Nutrition. 2004;7(3):443–452. doi: 10.1079/PHN2003538. available from: ISI:000222034100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Timperio A, Crawford D. Neighbourhood socioeconomic inequalities in food access and affordability. Health & Place. 2009;15(2):578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.09.010. available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6VH5-4TPX0RS-3/2/f4efd8917531052792761df20ca1a32d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulac J, Kristjansson E, Cummins S. A systematic review of food deserts, 1966-2007. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A105. available from: PM:19527577. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black C, Ntani G, Kenny R, Tinati T, Jarman M, Lawrence W, Barker M, Inskip H, Cooper C, Moon G, Baird J. Variety and quality of healthy foods differ according to neighbourhood deprivation. Health Place. 2012;18(6):1292–1299. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.09.003. available from: PM:23085202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JL, Carpiano RM, Fleming S, Lauster N. Exploring the distribution of food stores in British Columbia: associations with neighbourhood socio-demographic factors and urban form. Health Place. 2011;17(4):961–970. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.04.002. available from: PM:21565544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JL, Macinko J. Neighborhoods and obesity. Nutrition Reviews. 2008;66(1):2–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2007.00001.x. available from: PM:18254880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block D, Kouba J. A comparison of the availability and affordability of a market basket in two communities in the Chicago area. Public Health Nutrition. 2006;9(7):837–845. doi: 10.1017/phn2005924. available from: ISI:000240867400006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boone-Heinonen J, Gordon-Larsen P, Kiefe CI, Shikany JM, Lewis CE, Popkin BM. Fast food restaurants and food stores: longitudinal associations with diet in young to middle-aged adults: the CARDIA study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2011;171(13):1162–1170. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.283. available from: PM:21747011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovell-Benjamin AC, Hathorn CS, Ibrahim S, Gichuhi PN, Bromfield EM. Healthy food choices and physical activity opportunities in two contrasting Alabama cities. Health Place. 2009;15(2):429–438. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.08.001. available from: PM:18845469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoine T, Alvanides S, Lake AA. Assessing the obesogenic environment of North East England. Health Place. 2011;17(3):738–747. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.01.011. available from: PM:21450512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgoine T, Lake AA, Stamp E, Alvanides S, Mathers JC, Adamson AJ. Changing foodscapes 1980-2000, using the ASH30 Study. Appetite. 2009;53(2):157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2009.05.012. available from: PM:19467279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns CM, Inglis AD. Measuring food access in Melbourne: Access to healthy and fast foods by car, bus and foot in an urban municipality in Melbourne. Health & Place. 2007;13(4):877–885. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.02.005. available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6VH5-4NM5Y00-1/2/332fffdc2f31fc576b1b5eca928cfb9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande SS, Franco M, Gittelsohn J, Zonderman AB, Evans MK, Fanelli KM, Gary-Webb TL. Healthy food availability and the association with BMI in Baltimore, Maryland. Public Health Nutr. 2011;14(6):1001–1007. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010003812. available from: PM:21272422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi CE, Kawachi I, Subramanian SV, Adamkiewicz G, Sorensen G. The relationship between diet and perceived and objective access to supermarkets among low-income housing residents. Social Science and Medicine. 2012a;75(7):1254–1262. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.05.014. available from: PM:22727742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian SV, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: A systematic review. Health Place. 2012b;18(5):1172–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006. available from: PM:22717379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charreire H, Casey R, Salze P, Simon C, Chaix B, Banos A, Badariotti D, Weber C, Oppert JM. Measuring the food environment using geographical information systems: a methodological review. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(11):1773–1785. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000753. available from: PM:20409354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke G, Eyre H, Guy C. Deriving indicators of access to food retail provision in British cities: Studies of Cardiff, Leeds and Bradford. Urban Studies. 2002;39(11):2041–2060. available from: ISI:000178382600005. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke P, Ailshire J, Melendez R, Bader M, Morenoff J. Using Google Earth to conduct a neighborhood audit: Reliability of a virtual audit instrument. Health & Place. 2010;16(6):1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.08.007. available from: ISI:000284135900019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coveney J, O’Dwyer LA. Effects of mobility and location on food access. Health & Place. 2009;15(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.01.010. available from: ISI:000261636300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, Macintyre S. A systematic study of an urban foodscape: The price and availability of food in Greater Glasgow. Urban Studies. 2002;39(11):2115–2130. available from: ISI:000178382600009. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, Petticrew M, Higgins C, Findlay A, Sparks L. Large scale food retailing as an intervention for diet and health: quasi-experimental evaluation of a natural experiment. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2005a;59(12):1035–1040. doi: 10.1136/jech.2004.029843. available from: ISI:000233271200008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S, Smith DM, Aitken Z, Dawson J, Marshall D, Sparks L, Anderson AS. Neighbourhood deprivation and the price and availability of fruit and vegetables in Scotland. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2010;23(5):494–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2010.01071.x. available from: PM:20831708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins SC, McKay L, Macintyre S. McDonald’s restaurants and neighborhood deprivation in Scotland and England. Am J Prev Med. 2005b;29(4):308–310. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.06.011. available from: PM:16242594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins S. Neighbourhood food environment and diet--Time for improved conceptual models? Preventive Medicine. 2007;44(3):196–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.11.018. available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6WPG-4MT551Y-1/2/4801a83220992bd21680f80d7312e128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health UK. Healthy Lives, Healthy People: Our strategy for public health in England. Her Majesty’s Stationery Office; London: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Duffey KJ, Gordon-Larsen P, Shikany JM, Guilkey D, Jacobs DR, Jr, Popkin BM. Food price and diet and health outcomes: 20 years of the CARDIA Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2010;170(5):420–426. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.545. available from: PM:20212177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn RA, Sharkey JR, Horel S. The effect of fast-food availability on fast-food consumption and obesity among rural residents: an analysis by race/ethnicity. Econ Hum Biol. 2012;10(1):1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.09.005. available from: PM:22094047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ecob R, Macintyre S. Small area variations in health related behaviours; do these depend on the behaviour itself, its measurement, or on personal characteristics? Health Place. 2000;6(4):261–274. doi: 10.1016/s1353-8292(00)00008-3. available from: PM:11027952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans AE, Jennings R, Smiley AW, Medina JL, Sharma SV, Rutledge R, Stigler MH, Hoelscher DM. Introduction of farm stands in low-income communities increases fruit and vegetable among community residents. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1137–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.007. available from: PM:22608130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhacker SE, Evenson KR, Rodriguez DA, Ammerman AS. A systematic review of fast food access studies. Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(501):e460–e471. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00715.x. available from: ISI:000289687500044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford PB, Dzewaltowski DA. Disparities in obesity prevalence due to variation in the retail food environment: three testable hypotheses. Nutrition Reviews. 2008;66(4):216–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00026.x. available from: ISI:000254385200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foresight. Tackling Obesities: Future Choices - Project Report. Government Office for Science; 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox R, Smith G. Sinner Ladies and the gospel of good taste: geographies of food, class and care. Health Place. 2011;17(2):403–412. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.07.006. available from: PM:20801073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco M, Diez-Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Lazo M, Brancati F, Caballero B, Glass T, Moore LV. Availability of healthy foods and dietary patterns: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2009;89(3):897–904. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26434. available from: PM:19144728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser LK, Edwards KL, Cade J, Clarke GP. The geography of Fast Food outlets: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(5):2290–2308. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7052290. available from: PM:20623025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller D, Cummins S, Matthews SA. Does transportation mode modify associations between distance to food store, fruit and vegetable consumption, and BMI in low-income neighborhoods? American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2013;97(1):167–172. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.036392. available from: ISI:000313135600022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giskes K, van Lenthe F, Avendano-Pabon M, Brug J. A systematic review of environmental factors and obesogenic dietary intakes among adults: are we getting closer to understanding obesogenic environments? Obesity Reviews. 2011;12(501):e95–e106. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00769.x. available from: ISI:000289687500012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glanz K, Sallis JF, Saelens BE, Frank LD. Healthy Nutrition Environments: Concepts and Measures. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2005;19(5):330–333. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-19.5.330. available from: http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&AN=17004178&site=ehost-live. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon C, Purciel-Hill M, Ghai NR, Kaufman L, Graham R, Van WG. Measuring food deserts in New York City’s low-income neighborhoods. Health Place. 2011;17(2):696–700. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2010.12.012. available from: PM:21256070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon-Larsen P, Guilkey DK, Popkin BM. An economic analysis of community-level fast food prices and individual-level fast food intake: A longitudinal study. Health & Place. 2011;17(6):1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.07.011. available from: ISI:000296671500007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson A, Christian JW, Lewis S, Moore K, Jilcott S. Food venue choice, consumer food environment, but not food venue availability within daily travel patterns are associated with dietary intake among adults, Lexington Kentucky 2011. Nutrition Journal. 2013a;12 doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-12-17. available from: ISI:000315384000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]