Abstract

Objective

This study was designed to investigate the efficacy and safety outcomes of ticagrelor in comparison with clopidogrel on a background of aspirin in elderly Chinese patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

Patients and methods

A double-blinded, randomized controlled study was conducted, and 200 patients older than 65 years with the diagnosis of ACS were assigned 1:1 to take ticagrelor or clopidogrel. The course of treatment was required to continue for 12 months.

Results

The median age of the whole cohort was 79 years (range: 65–93 years), and females accounted for 32.5% (65 patients). Baseline characteristics and clinical diagnosis had no significant difference between patients taking ticagrelor and clopidogrel; they were also balanced with respect to other treatments (P>0.05 for all). The risk of cardiovascular death was significantly lower in patients taking ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel, as was the risk of myocardial infarction (P<0.05 for all); there was no difference in the risk of stroke (P>0.05). Ticagrelor was more effective than clopidogrel in decreasing the primary efficacy end point (cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and stroke, P<0.05). The all-cause mortality was not significantly different between patients taking ticagrelor and clopidogrel (P>0.05). The difference in the risk of bleeding, platelet inhibition and patient outcomes major bleeding (life-threatening bleeding and others), and platelet inhibition and patient outcomes minor bleeding was not evident between patients taking ticagrelor and clopidogrel (P>0.05 for all).

Conclusion

The current study in elderly Chinese patients with ACS demonstrated that ticagrelor reduced the primary efficacy end point at no expense of increased bleeding risk compared with clopidogrel, suggesting that ticagrelor is a suitable alternative for use in elderly Chinese patients with ACS.

Keywords: acute coronary syndrome, Chinese elderly, clopidogrel, ticagrelor

Introduction

Morbidity of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) keeps a rapid growth in the People’s Republic of China, while aspirin and adenosine diphosphate P2Y12 receptor comprise the standard dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in patients with ACS.1 As a new developed P2Y12 receptor antagonist, ticagrelor is chosen to perform the optimization of DAPT due to its direct and reversible role.2–4 Because ticagrelor does not need metabolic activation and has less interindividual variation in drug action, it is a more potent antiplatelet drug in comparison with clopidogrel. In the global Phase III PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial, ticagrelor exceeded clopidogrel in reducing cardiovascular (CV) death.5 However, the finding is difficult to apply to specific age groups and individual national regions in the light of the diversity in patients enrolled in multinational trial. Age features as a strong predictor of adverse prognosis after ACS,6–8 and elderly patients with ACS are at increased risk of CV death as well as drug-related bleeding complications.9,10 In addition, difference in demographics, comorbidities, disease patterns, and genetic backgrounds of the Chinese patients with ACS leads to diverse prognostic result and bleeding risk.11–13 Hence, poor prognostic effect and excessive bleeding risk are viewed as the primary concerns for selecting antiplatelet drugs for elderly Chinese patients with ACS.14 However, it remains uncertain on the choice of clopidogrel vs ticagrelor in the therapy of elderly Chinese patients with ACS. The current study was designed to investigate the efficacy and safety outcomes of ticagrelor in comparison with clopidogrel on a background of aspirin in elderly Chinese patients with ACS.

Patients and methods

Study participants

A double-blind, randomized controlled study was conducted in Harbin, People’s Republic of China. A total of 200 patients older than 65 years were recruited from August 2013 to November 2014 and randomly assigned 1:1 to take ticagrelor or clopidogrel in double-blind fashion with the least delay after admission. Based on the sample size calculation (α=0.05, β=0.2), 200 cases were enough for this study. Patients were included with the diagnosis of ACS made according to the European Society of Cardiology guideline, and excluded if they: 1) had any contraindication against the use of P2Y12 inhibitors, 2) were under DAPT, anticoagulation, and fibrinolytic therapy, 3) had active bleeding or increased bleeding risk such as malignancy, surgery, trauma, fracture, or organ biopsy, 4) had clinically significant out-of-range values for platelet count or hemoglobin, and 5) had renal function failure requiring dialysis, hypertension with systolic blood pressure >180 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure >110 mmHg, or cardiogenic shock with systolic blood pressure <80 mmHg lasting for >30 minutes.2 The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Fourth Clinical College of Harbin Medical University and performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki. Each participant provided written informed consent to be included in the study.

Dosing regimens

The initial loading dose (LD) of drug was administered as soon as possible after randomization with the first maintenance dose (MD) administered at the usual time. Clopidogrel was administered at a 300 mg LD with an MD of 75 mg once daily. Ticagrelor was administered at a 180 mg LD, and then an MD of 90 mg twice daily. All patients took aspirin at an LD of 300 mg followed by an MD of 100 mg once daily, unless aspirin was intolerant. The course of treatment was required to continue for 12 months.

Follow-up procedures

Follow-up visit was scheduled at 12 months after randomization or until death occurred before 12 months, with a safety follow-up visit 1 month after the end of treatment. No patient dropped out during the study period. The primary efficacy end point was the composite of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, or CV death. The secondary efficacy variables were MI, stroke, CV death, all-cause death, recurrent cardiac ischemia, transient ischemic attack, and other arterial thrombotic events. The safety variables were bleeding (any bleeding episode), PLATO major bleeding (life-threatening and others), and PLATO minor bleeding (requiring medical intervention). All variables were determined as defined in PLATO trial.5,15,16

Statistical analyses

Continuous variable was described as mean (with standard deviation) or median (with interquartile range), and categorical variable as number. Continuous variable was compared with Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test, and categorical variable with chi-square test. End event was analyzed with Cox regression, and event risk in patients taking ticagrelor relative to patients taking clopidogrel was described as hazard ratio with 95% confidence interval. Survival curves were generated by means of Kaplan–Meier estimates. All analyses were conducted using SPSS 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and with two-sided significance level of 0.05.

Results

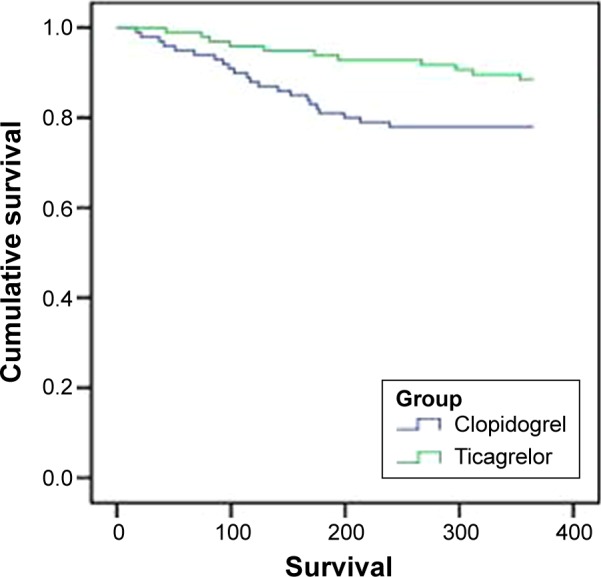

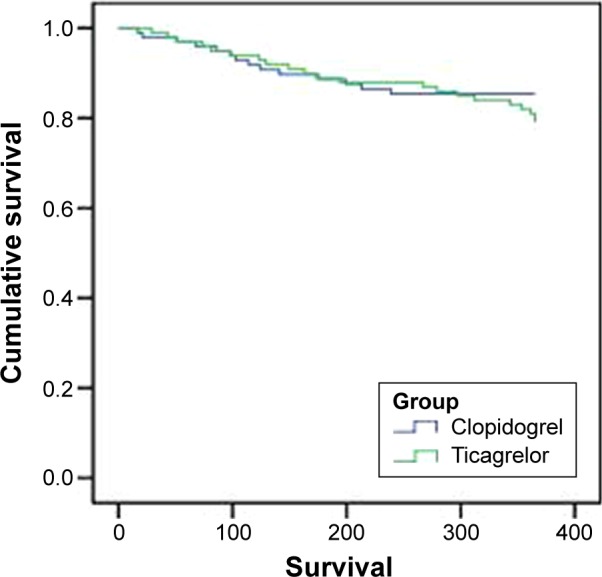

The median age of the whole cohort was 79 years (range: 65–93 years), and females accounted for 32.5% (65 patients). As shown in Table 1, baseline characteristics and clinical diagnosis had no significant difference between patients taking ticagrelor and clopidogrel; they were also balanced with respect to other treatments (P>0.05 for all). The risk of CV death was significantly lower in patients taking ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel, as was the risk of MI (P<0.05 for all; Table 2); there was no difference in the risk of stroke (P>0.05). Ticagrelor was more effective than clopidogrel in decreasing the primary efficacy end point (CV death, MI, and stroke, P<0.05). The all-cause mortality was not significantly different between patients taking ticagrelor and clopidogrel (P>0.05). The risk in the composite of all-cause death, MI, and stroke and the composite of CV death, MI, stroke, recurrent cardiac ischemia, transient ischemic attack, and other arterial thrombotic events was similar in patients taking ticagrelor and clopidogrel (P>0.05 for all). The difference in the risk of bleeding, PLATO major bleeding (life-threatening bleeding and others), and PLATO minor bleeding was not evident between patients taking ticagrelor and clopidogrel (P>0.05 for all). Kaplan–Meier estimates of the composite of CV death/MI/stroke and bleeding for all the patients using clopidogrel or ticagrelor are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics, diagnosis, and management

| Variables | Clopidogrel (n=100) | Ticagrelor (n=100) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline characteristics, n (%) | |||

| Age, median (interquartile range) | 80 (74–86) | 79 (76–85) | 0.833 |

| Female | 34 (34%) | 31 (31%) | 0.651 |

| Smoker | 41 (41%) | 37 (37%) | 0.562 |

| DM | 39 (39%) | 42 (42%) | 0.666 |

| Dyslipidemia | 79 (79%) | 84 (84%) | 0.363 |

| Hypertension | 82 (82%) | 79 (79%) | 0.592 |

| Angina pectoris | 36 (36%) | 40 (40%) | 0.560 |

| Prior MI | 15 (15%) | 17 (17%) | 0.700 |

| Prior PCI | 6 (65%) | 3 (3%) | 0.495 |

| Prior CABG | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| CHF | 9 (9%) | 13 (13%) | 0.366 |

| TIA | 14 (14%) | 16 (16%) | 0.692 |

| Nonhemorrhagic stroke | 10 (10%) | 11 (11%) | 0.818 |

| PAD | 7 (7%) | 5 (5%) | 0.552 |

| CKD | 13 (13%) | 12 (12%) | 0.831 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.755 | ||

| STEMI | 32 (32%) | 37 (37%) | |

| NSTEMI | 47 (47%) | 44 (44%) | |

| UA | 21 (21%) | 19 (19%) | |

| Risk, n (%) | |||

| TIMI risk score ≥3 | 95 (95%) | 96 (96%) | 0.733 |

| Management, n (%) | |||

| Aspirin | 100 (100%) | 100 (100%) | |

| Nitrates | 89 (89%) | 90 (90%) | 0.818 |

| ACEI/ARB | 67 (67%) | 61 (61%) | 0.377 |

| β-Blocker | 74 (74%) | 69 (69%) | 0.434 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 63 (63%) | 69 (69%) | 0.370 |

| Statin | 79 (79%) | 83 (83%) | 0.471 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 33 (33%) | 31 (31%) | 0.762 |

| Coronary angiography | 83 (83%) | 86 (86%) | 0.558 |

| PCI during study | 71 (71%) | 75 (75%) | 0.524 |

| CABG during study | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHF, congestive heart failure; CKD, chronic kidney disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; MI, myocardial infarction; NSTEMI, non-ST-segment elevation MI; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI, ST-segment elevation MI; TIA, transient ischemic attack; UA, unstable angina; TIMI, thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

Table 2.

Efficacy and safety end points

| End points | Clopidogrel (n=100) | Ticagrelor (n=100) | HR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Efficacy end points, n (%) | ||||

| Composite of CV death/MI/stroke | 22 (22%) | 11 (11%) | 0.473 (0.230–0.976) | 0.043 |

| Composite of all-cause mortality/MI/stroke | 22 (22%) | 13 (13%) | 0.558 (0.281–1.108) | 0.095 |

| Composite of CV death MI/stroke/RI/TIA/other ATEs | 26 (26%) | 19 (19%) | 0.688 (0.381–1.243) | 0.216 |

| All-cause death | 16 (16%) | 9 (9%) | 0.534 (0.236–1.209) | 0.133 |

| CV death | 15 (15%) | 6 (6%) | 0.381 (0.148–0.982) | 0.046 |

| MI | 15 (15%) | 6 (6%) | 0.380 (0.148–0.981) | 0.045 |

| Stroke | 3 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 0.623 (0.104–3.732) | 0.605 |

| Safety end points, n (%) | ||||

| Bleeding | 14 (14%) | 21 (21%) | 1.410 (0.717–2.774) | 0.319 |

| PLATO major bleeding | 6 (6%) | 8 (8%) | 1.250 (0.434–3.604) | 0.679 |

| Life-threatening bleeding | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 1.249 (0.279–5.582) | 0.771 |

| Others | 3 (3%) | 4 (4%) | 1.252 (0.280–5.593) | 0.769 |

| PLATO minor bleeding | 8 (8%) | 13 (13%) | 1.531 (0.634–3.694) | 0.343 |

Abbreviations: ATEs, arterial thrombotic events; CI, confidence interval; CV, cardiovascular; HR, hazard ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; PLATO, PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes; RI, recurrent cardiac ischemia; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of composite of CV death/MI/stroke for all patients using clopidogrel or ticagrelor.

Abbreviations: CV, cardiovascular; MI, myocardial infarction.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimate of bleeding for all patients using clopidogrel or ticagrelor.

Discussion

The current study was the first study comparing the efficacy and safety between clopidogrel and ticagrelor in elderly Chinese patients, and demonstrated that ticagrelor had the superior efficacy and similar safety relative to clopidogrel regardless of age and race. Results from the current study confirmed that patients taking ticagrelor were at lower risk of MI and CV death without more common bleeding compared with clopidogrel. Lower risk of the primary efficacy end point was also noted in patients taking ticagrelor. However, there was no differential treatment effect for all-cause mortality and other efficacy end points between ticagrelor and clopidogrel.

With the extension of lifetime and the expansion of elderly in the People’s Republic of China, the Chinese elderly will account for an increasing proportion of patients with ACS in the future.1,17,18 An old age is known to be a strong predictor of thromboembolic and bleeding events as well as corresponding elevation in death risk in patients with ACS.6–10,19 Moreover, clinical prognosis of elderly with ACS is often further complicated by more common comorbidity.20,21 DAPT is crucial to prevent adverse events in patients with ACS, and ticagrelor is likely to be more suitable for DAPT.2–4 However, the evaluation of ticagrelor is insufficient in the elderly Chinese patients with ACS. The current study showed that ticagrelor had greater treatment effect on elderly Chinese patients with ACS compared with clopidogrel, and proved that ticagrelor is a more potent inhibitor of adenosine-diphosphate-induced platelet aggregation than clopidogrel in elderly Chinese patients with ACS.

Chinese patients are susceptible to have bleeding events due to the difference in demographics, comorbidities, disease patterns, and genetic backgrounds.11–13 Compared with clopidogrel, ticagrelor has a direct, potent, fast-acting P2Y12 inhibition in normal patients,22,23 and has been suggested to have higher levels of platelet inhibition in the Chinese patients.24 In addition to race, increased platelet inhibition of ticagrelor has been reported for elderly patients.24 However, data for difference in bleeding risk according to age and race are limited. The PLATO trial found that ticagrelor had similar overall major bleeding risk compared with clopidogrel in patients with ACS.5 The current study realized that there was no significant difference in bleeding risk between ticagrelor and clopidogrel in elderly Chinese patients.

The current study had one limitation. Although it was the first study exclusively aimed at elderly Chinese patients with ACS and it provided significant information regarding the benefit and risk of ticagrelor application in elderly Chinese patients with ACS, its sample size was relatively small, and the large-scale study will be imperative to compare the efficacy and safety outcomes of ticagrelor and clopidogrel in elderly Chinese patients with ACS.

Conclusion

The current study in elderly Chinese patients with ACS demonstrated that ticagrelor reduced the primary efficacy end point at no expense of increased bleeding risk compared with clopidogrel, suggesting that ticagrelor is a suitable alternative for use in elderly Chinese patients with ACS.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Events Trial Investigators Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(7):494–502. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamm CW, Bassand JP, Agewall S, et al. ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation: the Task Force for the management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) in patients presenting without persistent ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2011;32(23):2999–3054. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation. American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2012;126(7):875–910. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e318256f1e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallentin L. P2Y12 inhibitors: differences in properties and mechanisms of action and potential consequences for clinical use. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(16):1964–1977. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallentin L, Becker RC, Budaj A, et al. PLATO Investigators Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(11):1045–1057. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boersma E, Pieper KS, Steyerberg EW, et al. Predictors of outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes without persistent ST-segment elevation. Results from an international trial of 9461 patients. The PURSUIT Investigators. Circulation. 2000;101(22):2557–2567. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.22.2557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eagle KA, Lim MJ, Dabbous OH, et al. GRACE Investigators A validated prediction model for all forms of acute coronary syndrome: estimating the risk of 6-month post-discharge death in an international registry. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2727–2733. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Granger CB, Goldberg RJ, Dabbous O, et al. Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events Investigators Predictors of hospital mortality in the global registry of acute coronary events. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(19):2345–2353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.19.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopes RD, Alexander KP. Antiplatelet therapy in older adults with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome: considering risks and benefits. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104(5 Suppl):16C–21C. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newby LK. Acute coronary syndromes in the elderly. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2011;12(3):220–222. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e328343e9ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatt DL, Pare G, Eikelboom JW, et al. CHARISMA Investigators The relationship between CYP2C19 polymorphisms and ischaemic and bleeding outcomes in stable outpatients: the CHARISMA genetics study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(17):2143–2150. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang TY, Chen AY, Roe MT, et al. Comparison of baseline characteristics, treatment patterns, and in-hospital outcomes of Asian versus non-Asian white Americans with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes from the CRUSADE quality improvement initiative. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(3):391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.03.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta RH, Parsons L, Peterson ED, National Registry of Myocardial Infarction Investigators Comparison of bleeding and in-hospital mortality in Asian-Americans versus Caucasian-Americans with ST-elevation myocardial infarction receiving reperfusion therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;109(7):925–931. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine GN, Jeong YH, Goto S, et al. Expert consensus document: world heart federation expert consensus statement on antiplatelet therapy in East Asian patients with ACS or undergoing PCI. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(10):597–606. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(16):1581–1598. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.James S, Akerblom A, Cannon CP, et al. Comparison of ticagrelor, the first reversible oral P2Y(12) receptor antagonist, with clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes: rationale, design, and baseline characteristics of the PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes (PLATO) trial. Am Heart J. 2009;157(4):599–605. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control (CDC) Trends in aging-United States and worldwide. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(6):101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jokhadar M, Wenger NK. Review of the treatment of acute coronary syndrome in elderly patients. Clin Interv Aging. 2009;4:435–444. doi: 10.2147/cia.s3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Avezum A, Makdisse M, Spencer F, et al. Impact of age on management and outcome of acute coronary syndrome: observations from the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) Am Heart J. 2005;149(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Cannon CP, et al. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology. Society of Geriatric Cardiology Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I: non–ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115(19):2549–2569. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.182615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, et al. American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology. Society of Geriatric Cardiology Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: in collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115(19):2570–2589. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.182616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurbel PA, Bliden KP, Butler K, et al. Response to ticagrelor in clopidogrel nonresponders and responders and effect of switching therapies: the RESPOND study. Circulation. 2010;121(10):1188–1199. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.919456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Storey RF, Angiolillo DJ, Patil SB, et al. Inhibitory effects of ticagrelor compared with clopidogrel on platelet function in patients with acute coronary syndromes: the PLATO (PLATelet inhibition and patient outcomes) PLATELET substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(18):1456–1462. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li H, Butler K, Yang L, Yang Z, Teng R. Pharmacokinetics and tolerability of single and multiple doses of ticagrelor in healthy Chinese subjects: an open-label, sequential, two-cohort, single-centre study. Clin Drug Investig. 2012;32(2):87–97. doi: 10.2165/11595930-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]