Abstract

Cardiovascular health disparities persist despite decades of recognition and the availability of evidence-based clinical and public health interventions. Racial and ethnic minorities and adults in urban and low-income communities are high-risk groups for uncontrolled hypertension (HTN), a major contributor to cardiovascular health disparities, in part due to inequitable social structures and economic systems that negatively impact daily environments and risk behaviors. This commentary presents the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities as a case study for highlighting the evolution of an academic-community partnership to overcome HTN disparities. Key elements of the iterative development process of a Community Advisory Board (CAB) are summarized, and major CAB activities and engagement with the Baltimore community are highlighted. Using a conceptual framework adapted from O’Mara-Eves and colleagues, the authors discuss how different population groups and needs, motivations, types and intensity of community participation, contextual factors, and actions have shaped the Center’s approach to stakeholder engagement in research and community outreach efforts to achieve health equity.

Keywords: Hypertension, Health Status Disparities, Health Care Disparities, Community-Based Participatory Research, Social Determinants of Health

Introduction

Despite widely available efficacious pharmacologic and behavioral therapies, uncontrolled hypertension (HTN) remains a significant public health issue, particularly among African Americans (AAs) and adults living in urban and low-income neighborhoods in the US.1-4 Disparities in HTN prevalence and control also contribute to persistent disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related outcomes, including deaths from heart disease and stroke.1,5,6 National estimates show that rates of uncontrolled HTN in AAs are among the world’s highest, contributing to an 80% higher rate of stroke mortality, a 50% higher rate of heart disease mortality, and a 320% higher rate of end-stage renal disease in AAs as compared with the general US population.1,2,5-8

In Baltimore, disparities in HTN and CVD-related outcomes are particularly striking. Heart disease and stroke are the #1 and #3 leading causes of total deaths in Baltimore City with African Americans bearing the greatest burden of mortality.9,10 CVD is a major contributor to the disparity in life expectancy between residents living in poorer neighborhoods vs those living in more affluent Baltimore neighborhoods.9-12 For instance, in the Greater Roland Park/Poplar Hill neighborhood, median household income exceeds $90,000; rate of heart disease deaths is 14.1/10,000 and average life expectancy is 83.1 years.11 However, just five miles away in the Madison/East End neighborhood, which lies adjacent to entities comprising the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, median household income is $30,389; rate of heart disease deaths jumps to 35.4/10,000 and life expectancy drops a dramatic 18.3 years to only 64.8 years.12

A significant body of literature implicates the complex, multifactorial nature of barriers to reducing disparities, including factors related to: individuals; family and social support systems; health care providers and organizational settings; the local community; and local and national policy environments.13,14 Furthermore, inequities in social determinants of health, including neighborhood poverty, crime rates, reduced access to high-earning jobs, housing, transportation, and healthy foods significantly contribute to these disparities.13,14 The convergence of these factors sustains an environment that threatens individual, family-level, and community-wide attempts to manage and/or reduce CVD risk, particularly in impoverished communities throughout Baltimore City.

In response to the well-documented link between pervasive social inequities and health disparities in the greater metropolitan Baltimore area, we established the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities (CVD Center).15 In this commentary, we share our experience cultivating a robust community-academic partnership through the auspices of a Community Advisory Board (CAB). We discuss the conceptual framework that articulates our CAB-Center partnership and outline our ongoing efforts to work collaboratively with the CAB to tackle proximal social determinants of health affecting CVD risk and management. Finally, we conclude with the steps we are taking to realize a vision of building a culture of health that intervenes at distal, fundamental root causes of poor health throughout Baltimore City, particularly the communities neighboring the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Development of the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities Community Advisory Board

Baltimore has a rich history of community-academic partnerships to address HTN. These partnerships, which found evidence supportive of the deployment of community health workers (CHWs) as a strategy for addressing HTN disparities, yielded significant associations between exposure to CHWs and improvements in several areas: appointment-keeping and continuity of care among adults using emergency departments as their usual source of care; reductions in blood pressure and increases in entry of care among young AA males; improved HTN self-management for adults receiving home visits from CHWs vs traditional care; and better HTN control for patients receiving activation coaching by CHWs vs educational newsletters only.16-20 Such efforts contributed to building an evidence base asserting the need for health care providers and researchers to engage local stakeholders (eg, individual patients, community members, nonprofit/community/faith-based organizations, educational and government institutions, insurers, and private businesses/employers) in order to fully leverage community-based resources in support of reducing HTN disparities.20

Although systematic reviews of community-based participatory research (CBPR) provide frameworks to guide successful community-academic partnerships, variations in effectiveness of these partnerships highlight the importance of a “fit for purpose” approach and combining community-academic collaboration with solid research methods.21-24 To this end, our Center established a formal CAB to ensure that our NIH-funded training core and three clinical trials to reduce HTN disparities responded to the needs and preferences of the community. CAB members are diverse stakeholders representing national organizations, health systems, educational partners, professional societies, government, community and faith-based organizations, community members, patients, and the business sector, as reflected in Table 1. We use a CBPR approach to equitably involve and build on strengths of CAB members in all phases of research.25 All partners share their expertise and assume responsibilities and co-ownership of Center outputs. CAB members participate in all phases of our research and training programs, from formulation to dissemination, including: development of grant proposals; piloting and refinement of research procedures and materials; recruitment of study participants; training staff and students; and manuscript authorship.

Table 1. Partnerships developed and sustained by the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities, 2010-2016.

| National Organizations | American Diabetes Association |

| American Heart & Stroke Association | |

| Urban League | |

| YMCA | |

| Medical / Health Systems | Baltimore Medical System, Inc. |

| CareFirst BlueCross BlueShield | |

| Charm City Clinic | |

| Individual Patients | |

| Johns Hopkins Community Physicians | |

| Johns Hopkins Health Care | |

| Maryland Men’s Cardiovascular Program | |

| Mid-Atlantic Association of Community Health Centers | |

| Park West Medical System | |

| Priority partners MCO | |

| Total Health Care | |

| University of MD Medical Center | |

| Educational Partners | Center on Urban Environmental Health / Environmental Justice Partnership |

| Coppin State University | |

| Johns Hopkins University | |

| Morgan State University | |

| University of Maryland, Baltimore, Department of Pharmacy | |

| University of Maryland School of Medicine | |

| Urban Health Institute | |

| Professional Societies | American College of Physicians |

| American Medical Association | |

| Association of Black Cardiologists | |

| Institute for Public Health Innovation | |

| MedChi (Maryland State Medical Society) | |

| Monumental City Medical Society | |

| Government | Baltimore City Health Department |

| Baltimore City Public Schools | |

| Baltimore County Health Department | |

| Maryland Dept. of Health and Mental Hygiene Office of Chronic Disease Prevention | |

| Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Office of Minority Health | |

| Maryland House of Delegates | |

| Maryland State Senate | |

| Community Organizations | Associated Black Charities |

| Baltimore Food Policy Council | |

| Belair-Edison Healthy Community Coalition | |

| The Diabetes Awareness Project | |

| Health Freedom, Inc. | |

| Health Care Access Maryland | |

| Men and Families Center | |

| Sisters Together and Reaching (STAR) | |

| United Against Inequities in Disease | |

| Upton Planning Committee | |

| Western Police District’s Community Affairs Council | |

| Faith-Based Organizations | Koinonia Baptist Church |

| Life Restoration Ministry | |

| St. Martin Church of Christ | |

| Zion Baptist Church | |

| Businesses | Break Open Coaching |

| Free State Information & Media Services | |

| IT Design Works | |

| OMRON | |

| The Pandit Group | |

| Santoni’s Market |

Iterative CAB Development Process – Challenges and Solutions

Our CAB has grown over the past 6 years, and member interactions have evolved. Initially, interactions between researchers and CAB members during stakeholder engagement meetings primarily involved researchers giving project updates followed by community members sharing updates from their organizations. Researchers would devise specific questions for community members before meetings, and interactions were very formal, with clear lines of “researchers” and “community” visible, down to who sat where. In response to members’ suggestions about ways to improve relationships, we held three in-depth, half-day retreats over 8 months. Our goals were to develop a clear vision and mission for the CAB, break down the “dividing lines” between researchers and community members, and create a more open exchange of ideas in the group. To inform the strategic planning process, we also administered a survey, the Partnership Self-Assessment Tool26 in 2013, which we repeated a year later. At baseline, among eight domains examined, community members rated the quality of our partnership highest for non-financial (eg, expertise, data, information, connections to others, credibility, influence) and financial (eg, money, space, equipment) resources, while overall satisfaction and CAB leadership ranked third and fourth. Over time, group assessments of effectiveness of leadership, administration/management, and decision making all improved significantly. We will continue using this tool to monitor progress and identify areas for improvement.

Our 2013 CAB research retreats and strategic planning process resulted in more collaborative and dynamic interactions, as well as the creation of guiding mission and shared vision statements and bylaws (Table 2). Since financial resources are critical to the success and durability of the CAB-Center partnership, the Center has invested approximately $250,000 to 1) support a dedicated community-liaison staff member, with expertise in CBPR and extensive relationships with local stakeholder groups, to facilitate regular communication between CAB members and the research team; 2) provide gifts and honoraria for CAB members; and 3) cover the costs incurred from community outreach events as well as CAB meetings and retreats. The CAB is co-led by the executive director of a highly regarded local community-based organization (the executive director is a life-long advocate for social justice in Baltimore City) and an academic researcher. During our meetings, CAB members and researchers interact in breakout working groups that report updates to the larger group, and our meetings now feature dedicated time for open discussion where community members can reach out to researchers for support with grant writing, health-related programing for events, data for advocacy with policy-makers, and their own advisory boards.

Table 2. Community Advisory Board mission and vision statements, Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

| Vision | A healthy community free of disparities in heart disease. |

| Mission | Our mission is to provide guidance in all activities of the Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities to ensure equitable care and improve the heart health of the community. |

| We will accomplish this by: | |

| - Helping the Center to provide education and outreach to the community regarding the conduct and results of research. | |

| - Working in partnership with the Center in all phases of research from planning, implementation, and evaluation to translation and dissemination. | |

| - Representing the Baltimore community, which includes local residents, patients, health care providers, researchers, students, faith-based organizations, community-based organizations, educational institutions, business leaders, and local and state government officials. |

These changes facilitated a more engaged partnership. Our interactions progressed from simply providing updates and reports, to engaging in honest, open conversations, in which both sides listen carefully to one another’s viewpoints, respect different perspectives, and demonstrate commitment by responding with concern and tangible support when able, and with care or referrals to other resources when appropriate. Challenges to initial engagement and sustainability, and the solutions employed to address them, are summarized in Table 3. In addition, we compiled a report, Community, Patient, and Clinic Stakeholder Input and Impact on Center Research and Training Activities, which is available from the corresponding author).

Table 3. Challenges to engagement between CAB members and CVD Center researchers.

| Challenge | Solution |

| Cultivating authentic relationships between CAB members and the Center’s researchers | 3 half-day retreats, over an 8-month period, to build rapport between CVD Center researchers and CAB members and strengthen relationships |

| Quarterly CAB meetings with designated time built in for all participants to talk among themselves and forge friendships with one another | |

| Co-hosting events in the community (eg, the family-oriented event, “Celebrate Your Heart,” keynote presentations at faith-based and health care organization, academic-community panels to discuss how to strengthen communication and relationships during times of civil unrest) | |

| Center researcher participation in community/stakeholder events (eg, Maryland Million Hearts Symposium, Urban League’s Obesity Awareness Day, Why Women Cry Conference) | |

| Provision of health education, nutritional counseling, and blood pressure screenings at local health fairs and block parties | |

| Communication | Weekly newsletter about Center’s events and information about local events from CAB members |

| Hiring a full-time stakeholder engagement and outreach manager to facilitate bidirectional information flow between CAB and research team | |

| Building trust between the CAB and the Center’s researchers | Transparency about each individual’s motivations behind participation in the CAB during retreats and quarterly meetings |

| Sharing study proposals, intervention protocols, job descriptions with CAB members | |

| Modifying study designs and protocols based on feedback received from CAB members | |

| Enlisting CAB members’ participation in study work groups | |

| Defining a shared agenda between CAB members and Center researchers | Co-developed mission and vision statements |

| CAB jointly led by a CAB member and an academic researcher | |

| Continuous review of the core values governing the CAB-Center partnership | |

| Sustainability | Garnering specific support and resources from our broader institution for community partners |

| Providing technical support for securing external funding to our community partners | |

| Advocating within our institution and seeking external funding for a stronger, more centralized and coordinated approach to community engagement in research, education, and health system change via the establishment of an Institute for Health Equity with a Community Outreach and Engagement Center | |

| Providing training for other researchers seeking to engage in CBPR |

Conceptual Framework for the CAB-Center Partnership

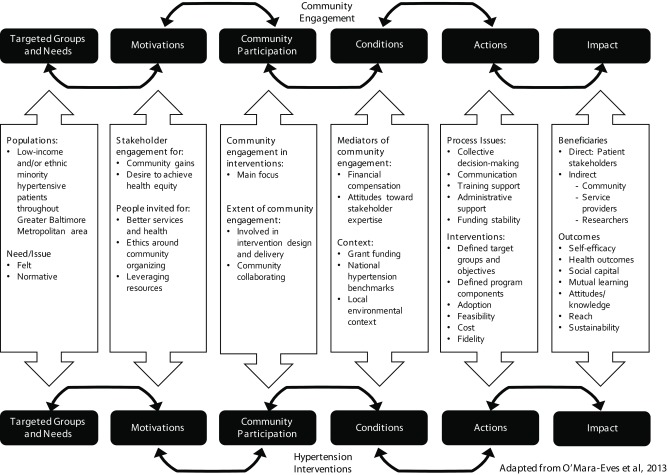

O’Mara-Eves et al’s conceptual framework for community engagement well captures the evolution of our CAB to its present state.23 We adapted the framework to reflect our Center’s approach to community engagement and pulled those aspects of the original framework that are the most salient to our CAB-Center Partnership (Figure 1). The framework’s intersecting inverted triangles are consistent with our belief in the inextricable link between community engagement and the development and implementation of effective interventions. O’Mara-Eves et al contend that community engagement and health interventions alike are dynamic processes, such that both phenomena influence, and are influenced by, a host of contextual factors. Thus, as illustrated in Figure 1, the arrows’ bi-directionality speaks to the fundamental interdependence of each stage on the community engagement and hypertension intervention continuums, and the interplay between the two.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework of community engagement. The Johns Hopkins Center to Eliminate Cardiovascular Health Disparities.

(Modified from O’Mara-Eves et al, 2013.)

In the context of the CVD Center, our target population consists of low-income and/or ethnic minorities residing in communities throughout the Baltimore metropolitan area. O’Mara-Eves and colleagues’ framework posits that a community’s needs run the gamut from felt needs (identified by community members), to expressed needs (inferred upon observing a community’s use of services), to comparative needs (discerned through comparing service use in similar communities) to normative needs (explicated through contrasting the community’s living conditions against expert-established societal norms).23 In our CAB-Center partnership, CAB members play a central role in identifying the felt needs of underserved communities (for example, education, outreach, and advocacy), shaping the perceived utility of our interventions in such a way as to influence their responsiveness to the normative needs elucidated through the Center’s researchers. Figure 1 explicates the motivations underlying community/stakeholder engagement, which are another component of O’Mara-Eves and colleagues’ framework: namely, a commitment to initiate and sustain community organizing around reducing cardiovascular health disparities and achieving health equity. For this reason, our CAB includes providers, community members, leaders of community-based organizations, and health system leaders to improve health and social service access and delivery and leverage resources across partnering entities, with the express purpose of improving health outcomes and quality of life in high-risk communities.

As mentioned, community participation mechanisms range from CAB members providing input on study design, implementation, and evaluation, to the employment of community members as CHWs to support blood pressure control and other facets of chronic disease self-management. These activities are implemented with an overlaying focus on mitigating the burden of social determinants of health, with an ultimate goal of directly intervening on fundamental causes of disparities. Community engagement is considered an essential component of our Center’s strategy and occurs through distal avenues (intervention construction and deployment) to proximal endeavors, achieved through lay health workers.

Consistent with O’Mara-Eves and colleagues’ assertions regarding the relationship between community engagement processes and health outcomes, we link the Center’s administrative infrastructure (eg, a dedicated community-liaison staff member) with the communication processes guiding our community engagement approaches. These factors, combined with intervention fidelity, cost, adoption, feasibility, and clearly defined populations and program components, are hypothesized as enhancing the association between CAB-Center engagement and a range of psychosocial, community-level, and cardiovascular health outcomes that directly benefit patients and indirectly benefit target communities, service providers, and research stakeholders. We will continue to use this framework to guide our CAB engagement process, as well as future inquiries exploring the link between implementation of community engagement activities and relevant study outcomes.

The CAB-Center Partnership’s Influence on Addressing Social Determinants of Health – Bridging the Proximal-Distal Intervention Spectrum

In their seminal work positing socioeconomic status as a fundamental cause of health inequities, Link and Phelan frame medical and public health interventions as occurring on a continuum, from those that address proximal, individual-level risk factors, to those that attempt to intercede at distal, systemic levels (such as housing policies) that drive health disparities.27 Our CAB-Center partnership has contributed to the development of contextualized interventions and activities that traverse the proximal-distal health intervention spectrum. For example, with respect to endeavors that are more proximal in nature, the Center’s Five Plus Nuts and Beans study28 highlights the intersection between O’Mara-Eves et al’s delineation of felt needs, as expressed by our CAB members (namely, such social determinants of health as food deserts and knowledge deficits around healthy eating, as well as the need for culturally tailored dietary advice) and normative needs (the empirical link between potassium deficiencies, excess salt intake, and elevated blood pressure). The Five Plus Nuts and Beans study used CBPR principles to guide the development of an 8-week, single center randomized trial that evaluated the impact of enhanced support to adopt a DASH diet. Our primary outcomes were blood pressure control, fruit and vegetable consumption, and urine potassium secretion. Those in the intensive intervention arm (DASH-Plus) received weekly coach-directed, tailored dietary advice that provided assistance with selecting higher potassium grocery items, as well as a weekly $30 food allowance. Participants in the minimal intervention group received a brochure about the diet. As a direct result of CAB members’ input, we partnered with the Baltimore City Health Department’s Virtual Supermarket, which allowed us to affordably deliver groceries in a food desert to those in the intervention group. The study resulted in statistically significant improvements in self-reported fruit and vegetable consumption and urine potassium excretion.

Other activities that aim to intercede at the individual/community level include participation in public forums (eg, Maryland Million Hearts Symposium, Urban League’s Obesity Awareness Day, and Why Women Cry Conference), sharing knowledge and experiences about cardiovascular risk factors, and educating community members about research methods and results, including how to become involved and contribute to research. We also provided health education, nutritional counseling, and blood pressure screenings at local health fairs and block parties, and we spoke on radio talk shows, including Urban Radio One’s “Our Health, Our Way” about our research on health disparities and how community members can use the results to improve their own health. CAB members are working with us to develop a program called “Heart of the Community,” supported by funds from the Johns Hopkins Office of Government and Community Affairs, to train community members to be “heart ambassadors,” providing blood pressure screening, education and peer support in the community.

In terms of approaching distal efforts to affect systemic change, center researchers have partnered with the community organizations in our CAB to advocate for policy change. We have interacted with policymakers at the local, state and federal level, including serving on the Maryland Healthcare Quality and Costs Council to advise lawmakers on the Maryland Health Improvement and Health Disparities Reduction Act of 2012,29 and speaking to Congress at the Profiles of Promise Launch30 to advocate for health disparities research funding. Recently, we partnered with the Association of American Medical Colleges and the University of Maryland to hold a special session at the 2015 Annual Meeting in Baltimore. This session (Communities, Social Justice and Academic Medicine)31 incorporated community perspectives on how academic medical centers, through their research, clinical and education missions, can impact social injustice and effectively partner with communities to address social determinants of health. While these endeavors are notable, we are continuously strategizing how best to cultivate and sustain a culture of health that intervenes at the fundamental root causes of cardiovascular disparities in East Baltimore. Our CAB membership, featuring representation from local and state politicians, national organizations, and community members, underscores the importance of engaging stakeholders operating at multiple levels of influence to support population health, with the goal of reducing the prevalence and impact of social factors that adversely influence health in Baltimore.

Conclusions

There are key lessons our Center has learned from engaging and building our CAB that may be applicable to others who are interested in fostering health equity through academic-community partnerships. We learned that one must begin by bringing a diverse and inclusive group of stakeholders to the table and finding ways to engage each of them in activities that are relevant both to individual stakeholders and the whole group, while utilizing their diverse expertise and perspectives. Members will choose to remain involved, or not, based on the manner in which they are engaged and the priorities that are set. Building a cohesive group that works well together is based on timing, shared values and commitment. We also learned to formalize priorities by engaging in strategic planning to develop the CAB’s mission, vision and goals early in the process, with annual reviews to reaffirm these constructs.

We have a strong, committed group and now fully appreciate the potential impact of our joint efforts. We have discovered that engagement is a dynamic and evolving process – our membership continues to expand and our research is developing in different directions based on what we learn from each other as well as evolving social conditions and events in our community. This requires flexibility and adaptability in our approach. For instance, although the social unrest that occurred in April 2015 shook our communities,32 it also brought us closer with opportunities to celebrate strengths and work together to enhance solidarity – members are now more likely to check in with each other when something happens in the community and reach out to support each other’s work and events. We also learned to better incorporate community feedback into research tools to improve our research studies – community members provided input on intervention materials, pilot-tested surveys, led focus groups, and gave feedback on research procedures, making the studies more appealing to participants and ultimately enhancing sustainability of effective components. In fact, the Five Plus Nuts and Beans study concluded with a 100% retention rate; the Achieving Blood Pressure Control Together (ACT) study,33 also housed in the Center, reached full recruitment in a fraction of the expected time; and Project ReDCHiP,34,35 the Center’s health system study, achieved high ratings of care and significant improvements in blood pressure among patients receiving care management. Community members remained engaged during times of scarce funding, and researchers kept the partnership a priority when funding was limited. Recently, academic and non-academic CAB members worked together on developing new research proposals, including a successful NIH-PCORI-sponsored grant (funded in 2015) that evolved out of our completed research trials and the unmet community needs identified by CAB members. Our adaptation of O’Mara-Eves et al’s conceptual framework organizes the philosophical underpinnings of our Center, guides activities, assists us in evaluating progress, and informs decision-making and translation of research into practice and policy to achieve equity and reduce hypertension disparities.

Researchers, clinicians, educators, community leaders and residents working together to achieve health equity need strong multi-sector partnerships, guiding principles and rigorous approaches to optimize conditions and actions that will maximize their impact. These partnerships, principles and approaches require significant investments of time and resources from all members of the partnership, but the potential rewards, in creating and sustaining a culture of health around cardiovascular disease, and achieving health equity, are enormous.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by a grant from the National, Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (P50HL105187). The authors would like to thank members of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research Community Research Advisory Council and to acknowledge the support of the Johns Hopkins Office of Community Health and the Johns Hopkins Office of Government and Strategic Affairs. The authors would also like to acknowledge the following persons for their contributions to the development and the work of the CAB: Dr. Michael Albert, Alyssa Allen, Jessica Ameling, Barbara Bates-Hopkins, Wanda Best, Emily Brown, Jeanne Charleston, Bishop Dr. Kevin Daniels, Patti Ephraim, Annette Fisher, Whitney Franz, Debra Gayles, Dr. M. Christopher Gibbons, Arlee Gist, Larry Gourdine, Dr. Wallace Johnson, LaPricia Lewis-Boyer, Rev. Dr. Mankekolo Mahlangu-Ngcobo, Richard Matens, Joy Mays, Dwyan Monroe, Dr. Gary Noronha, Leon Purnell, Dr. Rebecca Rios, Dr. Fadia Shaya, Valerie Sneed, Brian Taltoan, Ede Taylor, Kara Taylor, Patricia Tracey, Roderick Willis, Dr. H. C. Jessica Yeh, and Renee Youngfellow. The authors also want to remember the contributions of two members of the CAB who have passed away, Michael Carter and Dr. Elijah Saunders. The authors are also grateful to our clinical and payer stakeholders from the Johns Hopkins Department of Pharmacy, Johns Hopkins Health Care and Johns Hopkins Community Physicians. Lastly, the authors thank Won K. Choi for his help in the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Racial/Ethnic disparities in the awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension - United States, 2003-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62(18):351-355. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000. JAMA. 2003;290(2):199-206. 10.1001/jama.290.2.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gebreab SY, Davis SK, Symanzik J, Mensah GA, Gibbons GH, Diez-Roux AV. Geographic variations in cardiovascular health in the United States: contributions of state- and individual-level factors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(6):e001673. 10.1161/JAHA.114.001673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morenoff JD, House JS, Hansen BB, Williams DR, Kaplan GA, Hunte HE. Understanding social disparities in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control: the role of neighborhood context. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(9):1853-1866. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61(4):1-117. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr61/nvsr61_04.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1585-1592. 10.1056/NEJMsa012979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hall WD, Ferrario CM, Moore MA, et al. Hypertension-related morbidity and mortality in the southeastern United States. Am J Med Sci. 1997;313(4):195-209. 10.1097/00000441-199704000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klag MJ, Whelton PK, Randall BL, Neaton JD, Brancati FL, Stamler J. End-stage renal disease in African-American and white men. 16-year MRFIT findings. JAMA. 1997;277(16):1293-1298. 10.1001/jama.1997.03540400043029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. .Maryland State Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Maryland Vital Statistics Annual Report 2013. http://dhmh.maryland.gov/vsa/documents/13annual.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- 10. .Baltimore City Health Department Office of Epidemiologic Services Baltimore City Health Disparities Report Card 2013. http://health.baltimorecity.gov/sites/default/files/Health%20Disparities%20Report%20Card%20FINAL%2024-Apr-14.pdf. 2014. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- 11. .Ames A, Evans M, Fox L, Milam A, Petteway R, Rutledge R; Baltimore City Health Department Baltimore City 2011 Neighborhood Health Profile: Greater Roland Park/Poplar Hill. http://www.baltimorehealth.org/dataresearch.html. 2011. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- 12. .Ames A, Evans M, Fox L, Milam A, Petteway R, Rutledge R; Baltimore City Health Department 2011 Neighborhood Health Profile: Madison/East End. http://www.baltimorehealth.org/dataresearch.html. 2011. Accessed on April 21, 2016.

- 13.Davis AM, Vinci LM, Okwuosa TM, Chase AR, Huang ES. Cardiovascular health disparities: a systematic review of health care interventions. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(5)(suppl):29S-100S. 10.1177/1077558707305416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mueller M, Purnell TS, Mensah GA, Cooper LA. Reducing racial and ethnic disparities in hypertension prevention and control: what will it take to translate research into practice and policy? Am J Hypertens. 2015;28(6):699-716. 10.1093/ajh/hpu233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cooper LA, Boulware LE, Miller ER III, et al. Creating a transdisciplinary research center to reduce cardiovascular health disparities in Baltimore, Maryland: lessons learned. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):e26-e38. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bone LR, Mamon J, Levine DM, et al. Emergency department detection and follow-up of high blood pressure: use and effectiveness of community health workers. Am J Emerg Med. 1989;7(1):16-20. 10.1016/0735-6757(89)90077-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill MN, Bone LR, Kim MT, Miller DJ, Dennison CR, Levine DM. Barriers to hypertension care and control in young urban black men. Am J Hypertens. 1999;12(10 Pt 1):951-958. 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00121-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hill MN, Han HR, Dennison CR, et al. Hypertension care and control in underserved urban African American men: behavioral and physiologic outcomes at 36 months. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16(11 Pt 1):906-913. 10.1016/S0895-7061(03)01034-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. A randomized trial to improve patient-centered care and hypertension control in underserved primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(11):1297-1304. 10.1007/s11606-011-1794-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levine DM, Bone LR, Hill MN, et al. The effectiveness of a community/academic health center partnership in decreasing the level of blood pressure in an urban African-American population. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(3):354-361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Viswanathan M, Ammerman A, Eng E, et al. Community-based participatory research: assessing the evidence. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ). 2004;99(99):1-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahmed SM, Maurana C, Nelson D, Meister T, Young SN, Lucey P. Opening the black box: conceptualizing community engagement from 109 community-academic partnership programs. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2016;10(1):51-61. 10.1353/cpr.2016.0019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, McDaid D, et al. Community engagement to reduce inequalities in health: a systematic review, meta-analysis and economic analysis. Public Health Research. 2013;1(4). 10.3310/phr01040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Mara-Eves A, Brunton G, Oliver S, Kavanagh J, Jamal F, Thomas J. The effectiveness of community engagement in public health interventions for disadvantaged groups: a meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):129. 10.1186/s12889-015-1352-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173-202. 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. .National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (2008). Partnership Self-Assessment Tool. http://www.nccmt.ca/registry/view/eng/10.html. 2010. Accessed April 21, 2016.

- 27.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;35(Spec No):80-94. 10.2307/2626958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller ER III, Cooper LA, Carson KA, et al. A dietary intervention in urban African Americans: results of the “five plus nuts and beans” randomized trial. Am J Prev Med. 2016;50(1):87-95. 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reece EA, Brown AG, Sharfstein JM. New incentive-based programs: maryland’s health disparities initiatives. JAMA. 2013;310(3):259-260. 10.1001/jama.2013.7236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. .United for Medical Research Profiles of Promise Launch Event Videos. United for Medical Research website. http://www.unitedformedicalresearch.com/profiles-of-promise-launch-event-videos/. Accessed on April 21, 2016.

- 31. .Learn Serve Lead 2015. The AAMC Annual Meeting. Event website. http://www.cvent.com/events/learn-serve-lead-2015-the-aamc-annual-meeting/agenda-84345b2300604645bf80450becd1d00d.aspx. Accessed on April 21, 2016.

- 32.Wen LS, Sharfstein JM. Unrest in Baltimore: the role of public health. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2425-2426. 10.1001/jama.2015.5561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ephraim PL, Hill-Briggs F, Roter DL, et al. Improving urban African Americans’ blood pressure control through multi-level interventions in the Achieving Blood Pressure Control Together (ACT) study: a randomized clinical trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;38(2):370-382. 10.1016/j.cct.2014.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cooper LA, Marsteller JA, Noronha GJ, et al. A multi-level system quality improvement intervention to reduce racial disparities in hypertension care and control: study protocol. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):60. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hussain T, Franz W, Brown E, et al. The role of care management as a population health intervention to address disparities and control hypertension: a quasi-experimental observational study. Ethn Dis. 2016;26(3):285-294. 10.18865/ed.26.3.285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]