Abstract

Objectives

Perceived risk of HIV infection is thought to drive low adherence in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) trials. We explored the level of perceived risk of incident HIV infection in the Partners PrEP Study, in which adherence was generally high.

Methods

A cross-sectional questionnaire assessed perceived risk of HIV at 12 months after enrollment. Logistic regression was used to analyze the relationship between perceived risk and other demographic and behavioral variables.

Results

3226 couples from the Partners PrEP Study were included in this analysis. Only 15.4% of participants reported high or moderate perceived risk. Participants at high risk of acquiring HIV were slightly more likely to report high perceived risk (OR=1.60, 95%CI: 1.30–1.95, p<0.001); nevertheless, only 20% of participants with high risk reported high perceived risk.

Conclusions

Participants reported low perceived risk of HIV but were adherent to PrEP. Perceptions of risk are likely socially determined and more complex than Likert-scale questionnaires capture.

Keywords: PrEP, HIV, perceived risk, adherence, Kenya, Uganda

Introduction

The efficacy of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention has been evaluated in several clinical trials (1–6). These trials have produced encouraging yet varied results, with some studies finding significant HIV protection and others substantially less protection. Two trials, which studied the efficacy of PrEP strategies among young heterosexual African women, demonstrated no protective effect (2,4). Analyses done after those two trials were concluded found poor adherence in the study populations (7,8). Across PrEP trials, variations in PrEP adherence between different study populations are associated with the trial outcomes (9,10).

One hypothesis explaining low PrEP adherence in the trials is that enrolled young African women had low levels of perceived risk (9), and, as a result, low adherence to PrEP based on categorical risk questions asked of all participants and qualitative research among seroconverters (11). As a result, developing ways to increase reporting of higher perceived risk has been offered as a strategy to improve PrEP use.

In the Partners PrEP Study, a clinical trial of oral PrEP among heterosexual adults in long-term, serodiscordant relationships, adherence was high overall, with over 70% of participants having plasma tenofovir levels of at least 40ng/mL, which is consistent with regular daily dosing (12). In this study, PrEP was demonstrated to be highly efficacious for HIV prevention (1). In the present study, we aimed to describe the perceived risk for acquiring HIV infection in HIV seronegative partners enrolled in the Partners PrEP Study.

Methods

The Partners PrEP Study

Between July 2008 and November 2010, the Partners PrEP Study recruited 4747 heterosexual, mutually-disclosed, HIV-serodiscordant sexual couples from Kenya and Uganda and randomized the HIV uninfected partners to PrEP or placebo, as previously described (1). All couples received HIV testing and counseling as well as individual and couple-based risk-reduction counseling. HIV uninfected men were referred for circumcision services, and HIV infected partners were counseled to begin treatment and referred to local clinics as soon as they met national guidelines for initiating antiretroviral therapy. Use of placebo in the Partners PrEP Study was discontinued in 2011 after an interim review of HIV incidence found a highly significant risk reduction of 67% in the tenofovir study arm and 75% in the tenofoviremtricitabine study arm, each compared to placebo (1).

Seronegative participants were seen at monthly follow-up visits where they were tested for HIV and given 30 days’ worth of the appropriate study medication. Plasma samples were taken at the first monthly visit and then on a quarterly basis, and, for a subset of subjects, plasma levels of the study medication were evaluated with methods described previously (12). For this analysis, participants who had plasma tenofovir levels at 12 months of at least 40ng/mL, a level consistent with high adherence to the daily dosing regimen, were considered adherent. For HIV infected partners, CD4 counts and viral load were obtained every six months (1).

For both partners, demographic characteristics, including socio-economic indicators and relationship characteristics, were recorded at enrollment. Sexual behaviors (frequency of unprotected sex with partner, condom use at last sexual encounter with partner, number of new sexual partners, frequency of unprotected sex without partner) were recorded according to self-report at each visit (1).

Measurement of perceived HIV risk

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted within the Partners PrEP Study cohort in order to measure self-perceived risk of HIV infection at the study visit 12 months after enrollment. The interviewer-administered survey was implemented part-way through the trial, and thus some subjects who were enrolled early into the trial did not complete the assessment. For the present analysis, couples were included if the seronegative partner and the seropositive partner completed a follow-up assessment at the 12-month visit, including the risk-evaluation questionnaire.

In their preferred language, participants were asked to describe their perceived risk of acquiring HIV from their partner as ‘high,’ ‘moderate,’ ‘low,’ ‘none,’ or ‘I don’t know.’ For the purposes of this analysis, those participants who responded ‘high’ or ‘moderate’ were considered to have higher perceived risk. All other responses (‘low,’ ‘none,’ or ‘I don’t know’) were categorized as lower perceived risk. All participants who gave a response other than ‘I don’t know’ were asked to identify the reasons for their risk beliefs in a fixed response format.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were generated for perceived risk of infection as well as all relevant demographic and behavioral variables. Univariate logistic regression was used to calculate a crude odds ratio to describe associations between the severity of perceived risk versus demographic and behavioral variables, as well as versus an objective risk scoring tool developed and validated in the study population. The development and validation of this risk scoring tool, which accounts for age, number of children, marital status, condom use in the past 30 days, viral load of the infected partner, and circumcision of male uninfected partners, is described more fully elsewhere (13). An individual risk score of 5 or higher was considered an indicator of high risk for HIV infection. Variables found to be statistically significant in univariate analysis with p<0.05 were included in a multivariate analysis, with the exception of the calculated risk score. This variable was excluded from the multivariate analysis since the value was calculated using other demographic variables included in the multivariate model. Statistical analysis was conducted with STATA® Data Analysis and Statistical Software version 13 software (College Station, TX).

This research protocol was approved by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division and the Kenyatta National Hospital Ethics Review Committee.

Results

Of the 4747 seronegative partners enrolled in the Partners PrEP Study, 571 did not complete their 12 month follow-up visit or did not complete the visit concurrently with their partner; 892 completed their 12 month follow-up visit before the risk perception questionnaire was initiated or were not offered the questionnaire; and 58 had seroconverted by 12 months. The remaining 3226 seronegative adults were included in the present analysis: 36.7% (n=1213) were female and the average age was 34.2 years at enrollment. 26.3% (n=850) of participants reported receiving more than 8 years of education, and 70.5% (n=2272) reported having no income. Twelve months after enrollment, the HIV-uninfected participants’ seropositive partners had an average CD4 count of 512.7 cells/μL, and 9.7% (n=312) had begun ART. Plasma tenofovir levels were obtained from 441 participants at the 12-month follow-up visit. Of these, 66.7% (n=294) had plasma tenofovir levels of 40ng/mL or higher (Table I). These characteristics were representative of the Partners PrEP Study cohort as a whole (1).

Table I.

Participant Demographics

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

|

| ||

| Female | 1213 | 37.6 |

|

| ||

| Age | ||

|

| ||

| 18–25 yrs | 343 | 10.6 |

| 25–34 yrs | 1650 | 51.2 |

| 35+ yrs | 1233 | 38.2 |

|

| ||

| Income | ||

|

| ||

| Has income | 2666 | 82.6 |

|

| ||

| Education | ||

|

| ||

| >8 yrs | 990 | 30.7 |

|

| ||

| Married or Cohabitating with Partner | ||

|

| ||

| yes | 3192 | 99.0 |

|

| ||

| Number of Children at enrollment | ||

|

| ||

| none | 241 | 7.5 |

| 1 or 2 | 1005 | 31.2 |

| 3 or more | 1980 | 61.4 |

|

| ||

| Unprotected sex in partnership in last 30 days prior to 12-month study visit | ||

|

| ||

| yes | 505 | 15.7 |

|

| ||

| Circumcised (male seronegative partners only) | ||

|

| ||

| fully circumcised | 1136 | 56.6 |

|

| ||

| Plasma viral load of HIV-infected partner at 12 months | ||

|

| ||

| 50,000 copies/mL or higher | 1160 | 36.0 |

| 10,000–49,999 copies/mL | 814 | 25.2 |

| <10,000 copies/mL | 1252 | 38.8 |

|

| ||

| CD4 Count of HIV infected partner at 12m (n=3197) | ||

|

| ||

| 500+ cells/μL | 1364 | 42.7 |

| 200–499 cells/μL | 1725 | 54.0 |

| <200 cells/μL | 108 | 3.4 |

|

| ||

| HIV infected partner initiated ART by the 12-month study visit | ||

|

| ||

| yes | 312 | 9.7 |

|

| ||

| Plasma TDF at least 40ng/mL at 12-month study visit (n=441) | ||

|

| ||

| yes | 294 | 66.7 |

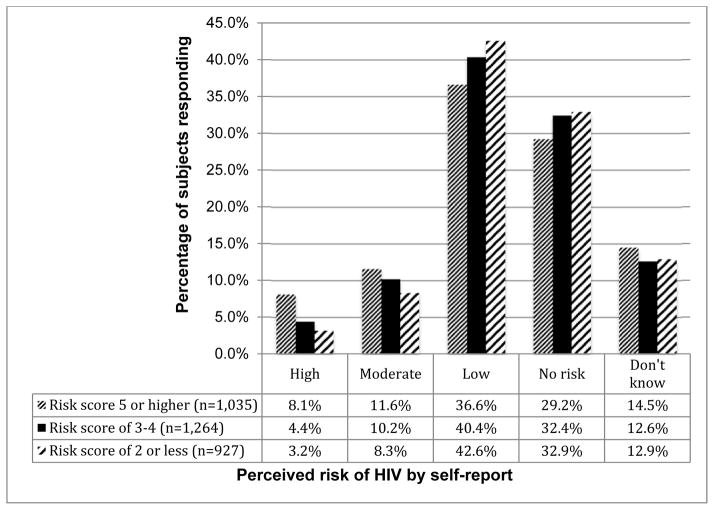

Of the 3226 participants, 15.4% (n=496) perceived themselves to be at ‘high’ or ‘moderate’ risk of HIV infection, while the majority of the participants reported being at ‘low’ risk (39.8%, n=1284) or ‘no risk’ (31.5%, n=1017). A minority (13.3%, n=429) of participants reported ‘don’t know’ for their quantification of perceived risk. Women were slightly more likely than men to respond ‘I don’t know’ about their perceived risk (17.2% vs. 11.0%, respectively; p<0.001). Otherwise, men and women had comparable degrees of perceived risk (Figure I).

Figure I.

Perceived Risk (Seronegative Partner) According to Calculated Risk Score

Reported condom use was the most commonly cited reason given by participants for their level of perceived risk. High condom use was identified as a reason for risk beliefs in more than 80% of those who reported being at ‘no risk’ or ‘low’ risk for infection, and low condom use was given as a reason for their perceived risk by 71.2% of participants who reported being at ‘high’ risk for infection. Those who reported themselves to be at ‘moderate’ risk of infection were split on these responses: 37.1% gave high condom use as a reason for their beliefs, and 46.0% gave low condom use as a reason. Additionally, approximately 15.5% of those who reported being at ‘no risk,’ ‘low’ risk, and ‘moderate’ risk, and 5.3% of those who reported ‘high’ risk reported that being on the study drug was a reason for their risk beliefs.

Finally, 22.3% (N=38) of those who responded that they were at ‘high’ risk of infection chose ‘other’ as one of their responses in lieu of the other choices made available by the fixed-response. Of these 38 participants, 25 reported some kind of condom failure or fear of condom failure. Other open-ended responses included the partner’s HIV-positive status, forced unprotected sex, having intercourse while the seropositive partner had an outbreak of genital ulcers, and stopping the study medication for breastfeeding purposes.

In univariate analysis, those with objective measures of HIV risk were slightly more likely to report high perceived risk of HIV infection. Higher risk was reported by 19.7% (n=204) of participants whose risk score (13) indicated higher risk for infection, compared to 13.3% (n=292) of those whose score indicated lower risk (OR=1.60, 95% CI: 1.30–1.95, p<0.001). Reporting unprotected sex with their known HIV positive partner in the past 30 days was strongly associated with an increased likelihood of reporting higher perceived risk of infection (OR=5.57, 95% CI: 4.49–6.91, p<0.001). Participants whose HIV seropositive partners had initiated ART in the previous 12 months were less likely to report perceived high risk for infection (OR=0.70, 95% CI: 0.48–0.99, p=0.049) than those whose partners had not yet initiated ART. In a multivariate analysis, neither gender nor plasma tenofovir levels (cut off: 40ng/mL) at 12 months after enrollment were associated with higher perceived risk. The HIV seropositive partner’s CD4 count at 12 month and the survival of the partnership beyond two years also showed no association. Only unprotected sex within the partnership in the past 30 days remained statistically significant in a multivariate model (Table II).

Table II.

Factors Related to Self-Reported High Risk of HIV Infection

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Variable | OR (95%CI) | p-value | OR (95%CI) | p-value |

| Risk Score of 5 or above (unadjusted OR) | 1.60 (1.30–1.95) | <0.001 | ||

| <25 years old | Ref | |||

| 25–34 years | 1.15 (0.84–1.59) | 0.384 | ||

| 35 yrs or older | 0.85 (0.60–1.19) | 0.334 | ||

| Female | 0.97 (0.80–1.19) | 0.801 | ||

| 8yrs or more of education | 1.16 (0.95–1.43) | 0.145 | ||

| Having any Income | 0.87 (0.68–1.11) | 0.252 | ||

| No children | Ref | -- | ||

| 1 or 2 children | 0.91 (0.62–1.33) | 0.625 | ||

| 3 or more children | 0.95 (0.66–1.37) | 0.784 | ||

| Married or cohabitating | 1.37 (0.48–3.90) | 0.559 | ||

| Unprotected sex w partner in last 30d | 5.57 (4.49-6.91) | <0.001 | 5.54 (4.46–6.87) | <0.001 |

| Unprotected sex w/o partner | 1.01 (0.71–1.43) | 0.964 | ||

| <10,000 copies | Ref | -- | ||

| 10,000–49,999 copies | 1.05 (0.83–1.33) | 0.676 | ||

| 50,000 copies or higher | 0.88 (0.66–1.17) | 0.377 | ||

| Together 2 years or more | 1.06 (0.80–1.40) | 0.693 | ||

| Physical or emotional abuse reported at 12mo | 2.22 (0.69–7.09) | 0.208 | ||

| Perpetrator of domestic abuse | 1.25 (0.47–3.32) | 0.652 | ||

| Sex partners outside the partnership | 1.08 (0.81–1.44) | 0.607 | ||

| Index reports sex partners outside partnership | 1.02 (0.71–1.46) | 0.911 | ||

| Index had unprotected sex w/others | 1.24 (0.73–2.12) | 0.441 | ||

| Index on ART (at 12mo) | 0.70 (0.48–0.99) | 0.049 | 0.76 (0.52–1.10) | 0.148 |

| Index CD4 count 500+ | Ref | -- | ||

| Index CD4 count 200–499 | 1.02 (0.84–1.24) | 0.861 | ||

| Index CD4 count <200 | 1.11 (0.66–1.88) | 0.694 | ||

| Plasma TDF level >40ng/mL | 0.98 (0.58–1.64) | 0.929 | ||

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis of perceived risk of HIV acquisition among HIV-uninfected partners in the Partners PrEP Study cohort, a minority reported high perceived risk of HIV, which was primarily associated lack of condom use in the prior 30 days. Self-perceived risk of HIV infection was not strongly related to actual risk of HIV acquisition or to adherence to the daily PrEP regimen, as indicated by plasma tenofovir levels above 40ng/mL. If low perceived risk was sufficient to explain the poor adherence to PrEP observed in other trials, then perceived risk should be higher in the Partners PrEP Study population than in other trials where adherence was low. To the contrary, nearly 85% of study participants in this survey reported that their perceived their risk of HIV infection was low. Overall, participants with objective measures of higher risk were more likely to report perceived high risk of infection, but still a minority of those at objectively higher risk reported perceiving higher risk.

In HIV prevention research, adherence to risk-reduction strategies is thought to be motivated by perceived risk (14–16). In this study, low levels of perceived risk was reported in a population in which more than two thirds of those sampled had plasma tenofovir levels above 40ng/mL (indicating high adherence to PrEP). These findings indicate that other factors may also motivate persons to adhere to PrEP. These findings are important in light of two earlier studies of PrEP, FEM-PrEP (2) and VOICE (17), both of which recruited heterosexual women and demonstrated little protective effect for oral PrEP in reducing the risk of HIV acquisition. In both of those trials, researchers attributed these study results in part to low perceived risk among the study participants which, in turn, led to poor adherence (7–9).

Both FEM-PrEP and the Partners PrEP Study used a 4-point Likert scale to assess perceived risk of HIV acquisition (no chance, small chance, moderate chance, and high chance in FEM-PrEP, and no risk, low risk, moderate risk, and high risk in the Partners PrEP Study) at 60 and 52 weeks after enrollment, respectively (7,9) This renders these findings largely comparable. Furthermore, FEM-PrEP asked participants to report their perceived risk of HIV infection during the subsequent four weeks, whereas the Partners PrEP Study asked participants to report their perceived risk in general. Therefore, the protocol followed in the Partners PrEP Study might have been expected to capture a greater frequency of perceived high risk than the FEM-PrEP study protocol. Nevertheless, perceived risk in the Partners PrEP Study was lower than in FEM-PrEP, with 84.6% and 74.8% of participants, respectively, reporting ‘low’ or ‘no risk’ (2) while drug adherence was higher (12). This indicates that perceived risk, as ascertained by this simple cross-sectional measure of risk perception, is not sufficient to motivate (or de-motivate) adherence to PrEP.

The limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting these results. First, even though the survival of the relationship beyond two years was not associated with perceived risk in this analysis many couples in the Partners PrEP Study had been sexually active for a relatively long time without transmitting HIV between them. Second, perceived risk was measured at 12 months, not at baseline. Both of these factors, especially in combination, could have led participants to believe that their risk of infection truly was low. The measurement of perceived risk at 12 months may have also decreased the variance in our study population. Though, the post-enrollment ascertainment of perceived risk analyzed here is similar to how perceived risk was measured in the FEM-PrEP study, it is nevertheless difficult to extrapolate the findings of this study to other populations with different demographic and behavioral characteristics or to populations in which ascertainment of perceived risk are taken at baseline.

Given these limitations, a few possible explanations for the incongruence of the relationship between perceived risk and adherence in the results from the Partners PrEP Study are worth considering. One is that perceived risk for HIV infection may be calculated differently by single and married heterosexual adults or by adults of different ages. For example, qualitative research among a sample of Partners PrEP Study participants found that PrEP adherence may be attributable to partners’ desire to maintain their relationship despite their discordance (10). The largely unmarried study population in the FEM-PrEP study may not have benefited from this supportive factor if the had not disclosed their participation in a PrEP trial.

Another potential explanation is that the measures of perceived risk used by these studies are insufficient to fully capture the complexity and variability of HIV risk perception. In other words, the true relationship between perceived risk of HIV and adherence to PrEP not withstanding, it is likely that the common approach of assessing perceived risk by self-report on a Likert scale is a poor method and produces data with the appearance of meaning but which is ultimately uninformative. Contemporary social research provides many reasons for suspecting that the brief questionnaires used in these studies were unable to capture meaningful information about perceived risk. Social perceptions of health-related risk encompass possible outcomes which might be viewed as deviant, amoral, or otherwise socially undesirable—a distinction that is fundamentally qualitative, not quantitative (18,19). Therefore, when research protocols aim to quantify individual perceptions of risk through empirical methods (e.g. when study participants are asked to rate their perceived risk on a Likert scale), these complex social dimensions of risk perception are collapsed into a few categories, and the meaning that each participant attributes to concepts such as ‘low’ and ‘moderate’ is subjective and heterogeneous.

The interpretation of empirical evidence is rarely, if ever, an exercise of pure reason. Rather, the very process of translating between evidence of risk and an accounting of personal risk is culturally informed (20). The perceived plausibility and tolerability of certain risks is often more important than empirical evidence in determining whether some risk will be recognized as valid or true (21). The determination about what even constitutes a risk from an individual’s perspective is tied to social norms and can vary greatly depending on personal experience, public opinion, discourse about that risk, and countless other factors. For example, of the 326 participants who reported being at ‘moderate’ risk of HIV infection in this study, 37% reported high levels of condom use as their reason behind this choice and 46% reported that low levels of condom use was their motivation. There is clearly no singular, meaningful way to interpret the responses of participants who claimed to be at ‘moderate’ risk because the term ‘moderate’ bore categorically different meanings for different participants.

Finally, even posing a question about risk has the potential to change or shape the response that is given. For example, research participants are often inclined to provide what they have learned to be the ‘right’ or socially desirable answer when asked about risk or risky behaviors, especially when that research concerns morally charged issues such as HIV and related high-risk behaviors like sexual practices and drug use (22). Study participants may also be inclined to alter their response to avoid association with clinically defined ‘high risk groups’ (drug users, men who have sex with men, sex workers, etc.), as these groups are frequently perceived in the popular imagination as clearly defined ‘types’ of persons who deviate from the social norm and are subject to negative stereotype (23–25). Therefore, participants may be disinclined to report being at high risk not only for reasons of comfort or social desirability but also for morally loaded reasons about what it means, in the social sense, to be ‘high risk.’

An individual’s response to questions about perceived risk may be useful in building rapport with care givers or in structured counseling efforts such as motivational interviewing (26). However, such questions cannot be used as a direct indicator of perceived risk in the context of PrEP delivery and are unlikely to be informative in determining whether initiating PrEP is appropriate for any given person. As risk perception is a complex social phenomenon, innovative techniques will be required to capture this variable in any meaningful way. In this endeavor, mixed method approaches, triangulation, and prospective evaluation may be beneficial.

Acknowledgments

Funding: The National Institute of Mental Health of the US National Institutes of Health (grant R01 MH095507) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (grant OPP47674) provided financial support for this study. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funders.

References

- 1.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):411–422. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1202614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–2599. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marrazzo JM, Ramjee G, Richardson BA, et al. Tenofovir-based preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(6):509–518. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–434. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1110711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Choopanya K, Martin M, Suntharasamai P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV infection in injecting drug users in Bangkok, Thailand (the Bangkok Tenofovir Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. The Lancet. 2013;381(9883):2083–2090. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: where have we been and where are we going? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;63(Suppl 2):S122–129. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3182986f69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, et al. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS Lond Engl. 2012;26(7):F13–19. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283522272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corneli A, Wang M, Agot K, et al. Perception of HIV risk and adherence to a daily, investigational pill for HIV prevention in FEM-PrEP. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2014;67(5):555–563. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ware NC, Wyatt MA, Haberer JE, et al. What’s love got to do with it? Explaining adherence to oral antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2012;59(5):463–468. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824a060b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corneli A, Perry B, Agot K, et al. Facilitators of adherence to the study pill in the FEM- PrEP clinical trial. PloS One. 2015;10(4):e0125458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2014;66(3):340–348. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahle EM, Hughes JP, LIngappa JR, et al. An empiric risk scoring tool for identifying high-risk heterosexual HIV-1 serodiscordant couples for targeted HIV-1 prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 1999. 2013;62(3):339–347. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e622d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60312-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Bushman BJ. Relation between perceived vulnerability to HIV and precautionary sexual behavior. Psychol Bull. 1996;119(3):390–409. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisingerich AB, Wheelock A, Gomez GB, et al. Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV preexposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: A multinational study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(1):e28238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mascolini M. HIV Prevention fails in all three VOICE arms, as daily Truvada PrEP fails. Presented at 20th conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections; 2013; Atlanta, GA. [Accessed October 4, 2015]. Available at: http://www.natap.org/2013/CROI/croi_09.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, et al. Women’s experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: The VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(2):e89118. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas M. Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. New York: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durkheim E. Elementary forms of religious life. New York: The Free Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dolan B. [Accessed March 25, 2012];The Art of Evidence. 2007 Available at: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/4963v0m4.pdf.

- 22.Douglas M, Wildavsky A. Risk and culture: An essay on the selection of technological and environmental dangers. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scott S, Prior L, Wood F, et al. Repositioning the patient: the implications of being “at risk”. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2005;60(8):1869–1879. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell ND, Shaw SJ. Incitements to discourse: Illicit drugs, harm reduction, and the production of ethnographic subjects. Cult Anthropol. 2008;23(4):688–717. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schiller NG, Crystal S, Lewellen D. Risky business: the cultural construction of AIDS risk groups. Soc Sci Med 1982. 1994;38(10):1337–1346. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown T. AIDS, risk and social governance. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2000;50(9):1273–1284. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00370-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kane S, Mason T. “IV Drug Users” and “Sex Partners”: The limits of epidemiological categories and the ethnography of risk. In: Herdt G, Lindenbaum S, editors. The time of AIDS: social analysis, theory, and method. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1992. pp. 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational interviewing. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]