Abstract

Introduction:

Cysteine protease are biological catalysts which play a pivotal role in numerous biological reactions in organism. Much of the literature is inscribed to their biochemical significance, distribution and mechanism of action. Many diseases, e.g. Alzheimer’s disease, develop due to enzyme balance disruption. Understanding of cysteine protease’s disbalance is therefor a key to unravel the new possibilities of treatment. Cysteine protease are one of the most important enzymes for protein disruption during programmed cell death. Whether protein disruption is part of cell deaths is not enough clear in any cases. Thereafter, any tissue disruption, including proteolysis, generate more or less inflammation appearance.

Review:

This review briefly summarizes the current knowledge about pathological mechanism’s that results in AD, with significant reference to the role of cysteine protease in it. Based on the summary, new pharmacological approach and development of novel potent drugs with selective toxicity targeting cysteine protease will be a major challenge in years to come.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cysteine protease, calpain, cathepsin, caspase, cystatin C, inflammation

1. INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common cause of dementia in the aging population. Due to its increasing prevalence it is in focus of numerous studies (1-4). This disease leads to significant cognitive defects affecting memory, insight, judgment, abstraction, and language functions (5). For a first time it was described 1906. Since this time neuropathologist tried to distinguish the nature of the amyloid material found in the senile plaque (5). Up to date the entire fundamental developing mechanism remains unknown.

It is clear that the isolation and partial sequencing of the meningovascular amyloid β-protein (Aβ) by George Glenner and Caine Wong in 1984 provided a turning point for modern research of AD (5, 6, 7). Although several species of Aβ peptides of 39-43 amino acids are produced in the brain, Aβ1-42 appears to be particularly critical in AD pathogenesis. Most mutations associated with autosomal dominant familial AD (FAD) increase the production or relative abundance of Aβ1-42 (8). Research into Alzheimer’s disease has so far contributed to development of symptomatic therapy, which had certain failures. These ups-and-downs prove evidences that there is an important brick missing in the wall of the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Luckily, preclinical researches provide us constantly with new information regarding the complex Alzheimer’s disease puzzle (9).

2. ROLE OF CYSTEINE PROTEASE IN ALZHEIMER DISEASE PATHOGENESIS

Emerging evidences show that cysteine protease play an important role in AD pathology, as well (10, 11, 12). Cysteine protease are class of abundant protease (13) which are widely spread in all living organisms (14). They include calpains, cathepsins, caspases, deubiquitinating enzymes, and small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) protease (13). It is known that cysteine protease are responsible for many biochemical processes occurring in living organisms. On the other hand, they are implicated in the development and progression of several diseases based on abnormal protein turnover, as well (14). Thus, precise regulation of their activity is essential for maintenance of homeostasis. It is based on proper gene transcription, regulation of expression, maturation and the rate of protease synthesis/degradation and their specific inhibitors: cystatin (14). Multiple lines of research have shown that cystatin C (CysC), cysteine protease inhibitor, plays protective roles in AD and other neurodegenerative diseases both in vitro and in vivo (15). AD pathology is characterized by deposition of oligomeric and fibrillar forms of Aβ in cerebral vessel walls, neurofibrillary tangles composed mainly of hyperphosphorylated tau and neurodegeneration with devastating consequences. In vitro studies show that CysC inhibits Aβ oligomerization and fibril formation as it binds Aβ. In vivo results from the brains and plasma of Aβ-depositing transgenic mice confirmed the association of CysC with the soluble, non-pathological form of Aβ and the inhibition of Aβ plaques formation (15). Moreover, in vitro studies showed that CysC protects neuronal cells from a wide range of insults that may cause cell death, including cell death induced by oligomeric and fibrillar Aβ. These data prove that reduced levels of CysC in AD contribute to increased neuronal vulnerability and impaired neuronal ability to prevent neurodegeneration (15).

3. ROLE OF CALPAINS IN ALZHEIMER DISEASE PATHOGENESIS

Calpains are calcium-dependent enzymes that determine the fate of proteins through regulated proteolytic activity. Not only do they participate in memory modulation but are considered as key to the pathogenesis of Alzheimer disease (AD) (16). In order to prevent deleterious consequences of massive proteolytic activity, calpain activation has to be precisely regulated. Nevertheless, these regulatory mechanisms decline with aging resulting in an increased calpain activity which are also abnormally activated under pathological conditions (17, 18, 4).

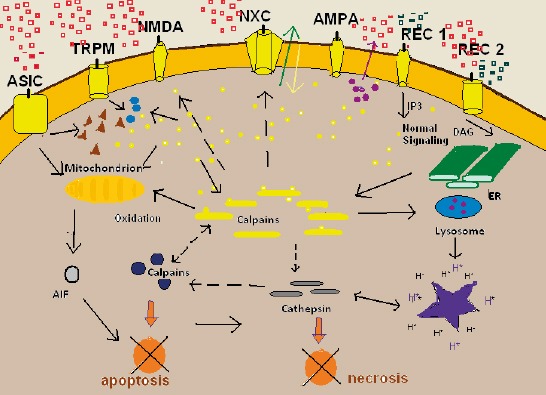

As is presented in figure 1. Calcium influx plays one of the central roles in cell degeneration in nerve tissue, apoptosis, programmed cell death, and necrosis, undesired cell death. As its known nerve cells live an entire lifetime. Some partial degeneration of cells occurs and reparation is permanent. Necrosis of nerve cells is undesired and tends toward degeneration of nerve tissue and malfunction. That’s the cornerstone of pathogenesis of AD. REC1 and REC2 are normal cell surface receptor for signal reception, and then the production of second messengers in cells. Other receptors are involved in cell death. Receptors AMPA, NMDA, TRMP7 and ASIC (see figure 1 for abbreviations), when activated, provoke influx of Ca++ ions in cell. Undesired and sharp increase of intracellular concentration of Ca++ ions tend toward cell death in both manner – apoptotic and necrotic. Subsequent activation of calpains occurs. Activated calpains process NMDA and NxC channels and cleave them. NMDA remains active, but NxC, which is involved in calcium extrusion, becomes inactivated. These events tend toward to further elevation of Ca++ in intracellular space. If the activation of calpains is inappropriate high neurons might undergo to apoptotic or necrotic death. Apoptotic inducing factor (AIF), processed in mitochondrion denote predominantly apoptosis, but predominant activation of calpains and cathepsins tend toward cell necrosis.

Figure 1.

Cell death, apoptosis and necrosis. Calcium plays a central role in degeneration of nerve cells. Cell membrane surface with many receptors. Some of them are involved in cell death and neurodegenation. Detailed explanation in text. ASIC, acid sensing ion channel; TRMP7 transient receptor potential cation channel; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; NaxC, Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; AMPA a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; AIF, appoptotic inducing factor; REC1 and REC2 physiologic cell receptor for signaling and processing second messengers

It is to note that energy depletion, lack of oxygen in nerve tissue, and hypoglycemic state is the most potent trigger of nerve cell necrosis. This status leads to shortage of energy to sustain the membrane potential and membrane depolarization occurs. Overstimulation of nerve cell’s membrane receptors NMDA and AMPA lead to Ca++ and Na+ overload in postsynaptic neurons. Additionally, secondary activation of voltage-gated Ca-channels leads to Ca++ overload in cells, and necrotic death in postsynaptic neurons. The term for these events is excitoxicity. It occurs in acute degenerative processes, like ischemia, anoxia, trauma, inflammation, epilepsy, and also in neurodegenerative diseases like AD.

The hyperactivation of calpain in AD is the result of several factors, including enhanced intracellular Ca2+ concentration and decreased calpastatin levels. Experiments performed using an AD culture model system showed that oligomeric Aβ induced a significant (5-fold) and instantaneous rise in Ca2+ in hippocampal neurons leading to calpain activation (19, 20, 21). The data obtained from other studies, which considered the role of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCC) in development of AD, showed that Aβ induces calpain activation by enhancing extracellular Ca2+ influx, which leads to neuronal cell dysfunction and death (20, 21, 22).

4. ROLE OF CALCIUM CHANNEL BLOCKER IN ISCHEMIC AND DAMAGED TISSUES

Taken all together, the theory that calcium blockers, e.g. the L-type voltage-gated calcium channel blockers verapamil, diltiazem (no-didropiridine, older formulations), isradipine and nimodipine (dihydropiridine, new formulations), exert neuroprotective effects may have therapeutic value in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease (23, 22, 24). All of noted calcium channel blockers improve oxygen supply in nerve tissue, and improve metabolic consumption). Memantin inhibates calpain activation via NMDA receptors because it is an open channel blocker (23). It enters in receptor–associated ion channel preferentially when it is excessively open, and its off-rate is relatively fast so that it does not substantially accumulate in the channel to interfere with normal synaptic transmission. Memantin is well toleranted, and it is the only NMDA antagonist now in clinical use (23). Moreover, isradipine is the most potent blocker as it prevents neurotoxicity at nanomolar levels (22, 24). On top of that, vascular dementia may benefit from calcium channel blockage due to relaxation of the cerebral vasculature, as it is caused by cerebral hypoperfusion (25).

5. ROLE OF CALPAINS IN SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION THROUGH MEMBRANE OF NERVE CELLS

Another prove which elucidates the role of calpains in AD is the fact that calpain inhibition through cysteine protease inhibitor and the highly specific calpain inhibitor restores normal synaptic function in both hippocampal cultures and hippocampal slices from the animal model of AD (16). Calpain inhibition also improves spatial-working memory and associative fear memory due to restoration of normal phosphorylation levels of the transcription factor CREB (16). Therefore, in order to provide enzyme inhibition and selective drug delivery, multifunctional liposomes have been tested (26, 27, 28, 29). When tacrine (30) was delivered through nasal mucosa within multifunctional liposomes made of cholesterol and phosphatidylcholine, its permeability has markedly increased due to liposome fusion with cellular membrane. Moreover, the addition of α-tocopherol has improved neuroprotective activity and antioxidant properties of liposomes (28). Therefore, selective delivery of calpain inhibitor within liposome might be a promising approach for AD treatment.

6. CATHEPSINS AND ALZHEIMER DISEASE

Cathepsins might participate in AD pathology, as well. Cathepsin B is a 30 kDa lysosomal cysteine protease of the papain subfamily of protease (31, 32). The main function of cathepsin B is the degradation of proteins that have entered the lysosomal system from outside the cell via endocytosis or phagocytosis (31). Cathepsin B is derived by cleavage of a proenzyme, procathepsin B, in the lysosomal endosomes. It is mainly active intracellularly but may also be secreted as a proenzyme and activated ex-tracellularly (31). Cathepsin B possesses the unique ability to act both as a dipeptidyl carboxypeptidase and an endopeptidase. Because it has two histidine residues (His 110 and His 111) in a 20 residue occluding loop on the primer side of its catalytic site, cathepsin B has greater carboxyldipeptidic then endopeptidic activity. Both proteolytic activities appear to be involved in the cathepsin B-dependent C-terminal truncation of Aβ1-42 (33). Impaired degradation of Aβ peptides could lead to Aβ accumulation, an early trigger of AD. Cystatin C (CysC) is an endogenous inhibitor of cysteine protease, including cathepsin B. Cumulatively, genetic knockout data (34), chemical inhibition (36, 34), and RNA silencing studies in cellular and animal models of AD (33), support the notion that cathepsin B inhibition reduces Aβ load and improves memory deficit in AD. Based on these data it has been hypothesised that inhibition of cathepsin B may be a therapeutic strategy in AD.

In contrast, in a mouse model of AD cathepsin B was recently demonstrated to act as an anti-amyloidogenic agent via C-terminal degradation of Aβ peptides (including Aβ 1-40 and Aβ 1-42). In fact, cathepsin B inhibition increased Aβ levels and plaque deposition. Cathepsin B cleaved fibrillar as well as nonfibrillar assemblies of Aβ1-42 into shorter Aβ peptides that are less pathogenic and amyloidogenic (33). Moreover, cystatin C has been suggested to be the main inhibitor of this anti-amyloidogenic action of cathepsin B (31). It still remains unclear if cathepsin B is mainly “good” or “bad” in AD pathogenesis and if the balance between cathepsin B and cystatin C is related to the risk of AD.

7. CASPASES IN ALZHEIMER DISEASE

Caspases (cysteinyl aspartate-specific protease) are enzymes from cysteine protease family which cleave peptide bonds specifically after an aspartic acid residue. They are normally present as inactive precursors in cells. Caspases are indispensable for the execution of apoptosis, following the cleavage of critical cellular proteins (37). These enzymes are participants in a proteolytic cascade leading to cell death via apoptosis. In neurons, the major „killer caspase” is thought to be caspase-3. The biochemical activation of apoptosis occurs through two general pathways: the intrinsic pathway, which is mediated by the mitochondrial release of cytochrome C and resultant activation of caspase-9; and the extrinsic pathway, originating from the activation of cell surface death receptors such as Fas, resulting in the activation of caspase-8 or -10. A third general pathway, which is essentially a second intrinsic pathway, originates from the endoplasmic reticulum and also results in the activation of caspase-9. In addition, other organelles, such as the nucleus and Golgi apparatus, also display damage sensors that are associated to apoptotic pathways. Thus, damage to any of several different cellular organelles may lead to the activation of the apoptotic pathway (38). Members of the caspase family play a critical role in AD- induced neuronal apoptosis (39). Therefore, their role in AD pathology has been widely examined (40, 39, 38, 37, 12, 41).

Caspases -1, -2, -3,–5, -6, -7, -8 and -9 have all been detected to be transcriptionally elevated in AD (41). Caspases may be playing a proximal role in the disease mechanisms underlying AD including promoting Aβ formation as well as linking plaques to neurofibrillary tangles (40). Therefore, caspase inhibitors may provide an effective strategy for treating AD (12). Therefore, in order to provide an overwhelming body of evidence, novel studies regarding these agents should be undertaken.

8. CONCLUSION

Alzheimer disease research is a huge challenge due to its increasing prevalence among elderly. A multifactorial hypothesis is probably the best way to integrate the many bits and pieces of evidence that link multiple molecular pathways to AD. An overwhelming body of evidence shows that protease play a crucial role in AD pathology. Moreover, protease are reasonably good drug targets, and many of the described avenues might open new perspectives for additional therapies or possibilities for new approaches to drug development in AD. In order to turn AD into a curable or preventable disease, future research should expand the emerging knowledge on AD.

Footnotes

• Author’s contribution: Samra Hasanbasic: Preparing and writing of manuscript, preparing and reviewing of final version. Alma Jahic: critical review of manuscript. Emina Karahmet: preparing of final version of manuscript, preparing of figure. Asja Sejranic: critical review of manuscript. Besim Prnjavorac: preparing of final version of manuscript, preparing of figure, critical review of manuscript.

• Conflict of interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(8):1119–22. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.8.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun B, Zhou Y, Halabisky B, Lo I, Cho SH, Mueller-Steiner S, Devidze N, Wang X, Grubb A, Gan L. Cystatin C-Cathepsin B axis regulates amyloid beta levels and associated neuronal deficits in an animal model of Alzheimer s disease. Neuron. 2008;60:247–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mebane-Sims I. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2009;5:234–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira A. Calpain Disregulation in Alzheimer’s Diesease. Biochemistry. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu MJ, Chen TF, Yip PK, Hua MS, Tang LY. Behavioral and psychologic symptoms in different types of dementia. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105(7):56–62. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colin L, Masters Dennis J. Selkoe. Biochemistry of Amyloid β-Protein and Amyloid Deposits in Alzheimer Disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(6) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palop JJ, Mucke L. Amyloid-β–induced neuronal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: from synapses toward neural networks. Nature Neuroscience. 2010;13:812–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mueller-Steiner S, Zhou Y, Arai H, Robertson ED, Sun B, Chen J, Wang X, Yu G, Esposito L, Mucke L, Gan L. Antiamyloidogenic and neuroprotective functions of cathepsin B: implications for Alzheimer s disease. Neuron. 2006;51:703–14. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangialasche Francesca, et al. Alzheimer’s disease: clinical trials and drug development. The Lancet Neurology. 2010;9(7):702–16. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70119-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee E, Eom JE, Kim HL, Baek KH, Jun KY, Kim HJ, Lee M, Mook-Jung I, Kwon Y. Effect of conjugated linoleic acid, µ-calpain inhibitor, on pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831(4):709–18. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Urbanelli L, Emiliani C, Massini C, Persichetti E, Orlacchio A, Pelicci G, Sorbi S, Hasilik A, Bernardi G, Orlacchio A. Cathepsin D expression is decreased in Alzheimer’s disease fibroblasts. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29(81):12–22. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rohn TT. The role of caspases in Alzheimer’s disease;potential novel therapeutic opportunities. Apoptosis. 2010;15(11):1403–9. doi: 10.1007/s10495-010-0463-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richard I. The genetic and molecular bases of monogenic disorders affecting proteolytic systems. J Med Genet. 2005;25:529–39. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.028118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grzonka Z, Jankowska E, Kasprzykowski F, Kasprzykowska R, Lankiewicz L, Wiczk W, Wieczerzak E, Ciarkowski J, Drabik P, Janowski R, Kozak M, Jaskólski M, Grubb A. Structural studies of cysteine protease and their inhibitors. Acta Biochimica Polonica. 2001;48(1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaur G, Levy E. Cystatin C in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;6(5):79. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trinchese F, Fa’ M, Liu S, Zhang H, Hidalgo A, Schmidt SD, Yamaguchi H, Yoshii N, Mathews PM, Nixon RA, Arancio O. Inhibition of calpains improves memory and synaptic transmission in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2008;1(8):2796–807. doi: 10.1172/JCI34254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sloane JA, Hinman JD, Lubonia M, Hollander W, Abraham CR. Age-dependent myelin degeneration and proteolysis of oligodendrocyte proteins is associated with the activation of calpain-1 in the rhesus monkey. J Neurochem. 2003;84(1):57–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferreira A, Bigio EH. Calpain-mediated tau cleavage: a mechanism leading to neurodegeneration shared by multiple tauopathies. Mol Med. 2011;17(7-8):676–85. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2010.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly BL, Vassar R, Ferreira A. β-amyloid-induced dynamin 1 depletion in hippocampal neurons: a potential mechanism for early cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(36):31746–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503259200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly BL, Ferreira A. β-amyloid-induced dynamin 1 degradation is mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors in hippocampal neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(38):28079–89. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605081200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danysz W, Parsons CG. Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid, glutamate, NMDA receptors and memantine - searching for the connections. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(2):324–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02057.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anekonda TS, Quinn JF, Harris C, Frahler K, Wadsworth TL, Woltjer RL. L-type voltage-gated calcium channel blockade with isradipine as a therapeutic strategy for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2011;41(1):62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsons CG, Stöffler A, Danysz W. Memantine: a NMDA receptor antagonist that improves memory by restoration of homeostasis in the glutamatergic system - too little activation is bad, too much is even worse. Neuropharmacology. 2007;53(6):699–723. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gholamipour-Badie H, Naderi N, Khodagholi F, Shaerzadeh F, Motamedi F. L-type calcium channel blockade alleviates molecular and reversal spatial learning and memory alterations induced by entorhinal amyloid pathology in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2013;237:190–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nimmrich V, Eckert A. Calcium channel blockers and dementia. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169(6):1203–10. doi: 10.1111/bph.12240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Airoldi C, Mourtas S, Cardona F, Zona C, Sironi E, D’Orazio G, Markoutsa E, Nicotra F, Antimisiaris SG, La Ferla B. Nanoliposomes presenting on surface a cis-glycofused benzopyran compound display binding affinity and aggregation inhibition ability towards Amyloid β1-42 peptide. Eur J Med Chem. 2014;85:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2014.07.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balducci C, Mancini S, Minniti S, La Vitola P, Zotti M, Sancini G, Mauri M, Cagnotto A, Colombo L, Fiordaliso F, Grigoli E, Salmona M, Snellman A, Haaparanta-Solin M, Forloni G, Masserini M, Re F. Multifunctional liposomes reduce brain β-amyloid burden and ameliorate memory impairment in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. J Neurosci. 2014;34(42):14022–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0284-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corace G, Angeloni C, Malaguti M, Hrelia S, Stein PC, Brandl M, Gotti R, Luppi B. Multifunctional liposomes for nasal delivery of the anti-Alzheimer drug tacrine hydrochloride. J Liposome Res. 2014;24(4):323–35. doi: 10.3109/08982104.2014.899369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ordóñez-Gutiérrez L, Re F, Bereczki E, Ioja E, Gregori M, Andersen AJ, Antón M, Moghimi SM, Pei JJ, Masserini M, Wandosell F. Repeated intraperitoneal injections of liposomes containing phosphatidic acid and cardiolipin reduce amyloid-βlevels in APP/PS1 transgenic mice. Nanomedicine. 2015;11(2):421–30. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tumiatti V, Minarini A, Bolognesi ML, Milelli A, Rosini M, Melchiorre C. Tacrine derivatives and Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17(17):1825–38. doi: 10.2174/092986710791111206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mort JS, Buttle DJ, Cathepsin B. Int J Biochem Cel Biol. 1997;29:715–20. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rawlings NM, Morton FR, Barrett AJ. The peptidase database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006);34:270–2. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klein DM, Felsenstein KM, Brenneman DE. Cathepsins B and L differentially regulate amyloid precursor protein processing. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:813–21. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.147082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hook VY, Kindy M, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Hook G. Genetic cathepsin B deficiency reduces beta-amyloid in transgenic mice expressing human wild-type amyloid precursor protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;386:284–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.05.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hook VY, Kindy M, Hook G. Inhibitors of cathepsin B improve memory and reduce beta-amyloid in transgenic Alzheimer disease mice expressing the wild-type, but not the Swedish mutant, beta-secretase site of the amyloid precursor protein. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:7745–53. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hook V, Toneff T, Bogyo M, et al. Inhibition of cathepsin B reduces beta-amyloid production in regulatedsecretory vesicles of neuronal chromaffin cells: evidence for cathepsin B as a candidate beta-secretase of Alzheimer’s disease. J Biol Chem. 2005;386:931–40. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rohn TT, Head E. Caspases as Therapeutic Targets in Alzheimer’s Disease: Is It Time to “Cut” to the Chase? Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2009;2(2):108–18. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bredesen DE. Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer`s disease: caspases and synaptic element interdependence. Molecular Neurodegeneration. 2009;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lester I, Binder, Angela L, Guillozet-Bongaart, Francisco Garcia-Sierra, Robert W. Berry, Tau, tangles, and Alzheimer’s disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1739:216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rohn TT, Rissman RA, Head E, Cotman CW. Caspase activation in the Alzheimer’s disease brain: tortuous and torturous. Drug News Perspect. 2002;15:549–57. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2002.15.9.740233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jana K, Banerjee B, Parida PK, Caspases A. Potential Therapeutic Targets in the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Transl Med. 2013 [Google Scholar]