Abstract

Objective

The ARC organizational intervention was designed to improve community-based youth mental health services by aligning organizational priorities with five principles of effective service organizations (i.e., mission-driven, results-oriented, improvement-directed, relationship-centered, participation-based). This study assessed the effect of the ARC intervention on youth outcomes and the mediating role of organizational priorities as a mechanism linking the ARC intervention to outcomes.

Methodology

Fourteen community-based mental health agencies in a Midwestern metropolis along with 475 clinicians and 605 youth (aged 5–18) served by those agencies were randomly assigned to the three-year ARC intervention or control condition. The agencies’ priorities were measured with the ARC Principles Questionnaire (APQ) completed by clinicians at the end of the intervention. Youth outcomes were measured as total problems in psychosocial functioning described by their caregivers using the Shortform Assessment for Children (SAC) at six monthly intervals.

Results

The rate of improvement in youths’ psychosocial functioning in agencies assigned to the ARC condition was 1.6 times the rate of improvement in agencies assigned to the control condition, creating a standardized difference in functioning of d = .23 between the two groups at the six month follow-up. The effect on youth outcomes was fully mediated by the alignment of organizational priorities described in the five ARC principles (d = .21).

Conclusions

The ARC organizational intervention improves youth outcomes by aligning organizational priorities with the five ARC principles. The findings suggest that organizational priorities explain why some community mental health agencies are more effective than others.

Keywords: ARC, organizational intervention, organizational priorities, youth mental health, service improvement

Mental health researchers, practitioners, and policymakers agree there is a need for improvement in community mental health services for youth (Garland et al, 2013; McMorrow and Howell, 2010; Warren et al, 2010). Studies of community mental health service systems confirm that they vary in effectiveness and that we know little about why some systems are more effective than others or how the effectiveness of community mental health services can be improved (NIMH, 2015). The limited use of evidence-based practices (EBPs) in community-based agencies has been identified as one factor that contributes to the variance in effectiveness; however, even agencies that adopt EBPs vary in their ability to improve services beyond usual care, so other factors must also play a role in service outcomes (Kazdin, 2015; NIMH, 2015; Weisz, Doss, & Hawley, 2005; Weisz, Krumholz, Santucci, et al, 2015; Weisz, Ugueto, Cheron et al, 2013). Previous studies suggest other factors affecting service outcomes include characteristics of the community-based organizations that provide the services (Glisson, Hemmelgarn et al, 2013; Glisson, Schoenwald et al, 2010; Patel, Weiss, Chowdhary et al, 2010; Weisz, Ugueto, Cheron et al, 2015). The current study focuses on the priorities of the organizations in which the services are embedded and assesses whether changes in those priorities can improve the outcomes of community-based care.

Organizational Priorities in Mental Health Services

A long history of organizational research explains that a variety of strategic goals and operational demands compete for emphasis in organizations as they attempt to survive and succeed (Quinn & Rohrbaugh, 1983; Schneider & Bowen, 1995). This research concludes that organizations that do similar work differ in the priorities they place on the competing goals and demands they face, and in the extent to which they align organizational priorities in a way that complements their efforts to be effective. An organization’s priorities reflect what is most important to the organization but an organization’s espoused and enacted priorities can be different – that is, organizations can say one thing and do another (Argyris & Schon, 1996; Pate-Cornell, 1990; Simons, 2002). Moreover, an organization can enact inconsistent and even conflicting priorities (Weick, 1979). The relative priorities placed on competing demands (that specify what is most important to the organization), the alignment of enacted and espoused priorities (ensuring the organization’s actions reflect what it says is most important), and the consistencies in its enacted priorities (the extent to which the organization’s priorities complement rather than conflict with each other) distinguish effective from ineffective organizations (Zohar & Hoffman, 2012).

Experience in our preliminary studies (Glisson, Dukes & Green, 2006; Glisson, Hemmelgarn et al, 2012, 2013; Glisson, Schoenwald et al, 2010) suggests that similar to other types of organizations, community mental health service agencies face competing demands (e.g., the demand for service quality versus the demand for service quantity, the demand for resources to develop a highly trained staff versus the demand for fiscal restraint), the difficulty of enacting espoused priorities (e.g., ensuring that a priority on improving client well-being is reflected in organizational practices, ensuring that the needs of the identified target population are actually being addressed), and conflicts created by inconsistent priorities (e.g., enacting rules to control clinician behavior that are inconsistent with specified treatments that require clinician discretion, assessing program performance based on client outcomes while limiting treatment options that individualize care). Inconsistent priorities in mental health agencies or the failure to enact espoused priorities can increase staff turnover, decrease staff morale, harm treatment relationships, limit commitment to improving care, and reduce the continuity of services. Misaligned priorities can create inappropriate referral procedures or delay access to treatment in the agency’s service structure, reducing service availability and responsiveness. Importantly, mental health service organizations can fail to enact priorities that promote effectiveness independently of their clinicians’ knowledge and skills. Perhaps more importantly, organizational strategies that provide mental health service agencies with the capacity for aligning priorities -- enacting consistent priorities that focus on improvements in client well-being and eliminating conflicting priorities within and across organizational levels -- should improve service effectiveness.

Successful organizational strategies for aligning priorities must include all levels of the organization and provide the flexibility for addressing each organization’s unique priority conflicts. Those who provide direct care (e.g., clinicians) are best able to identify conflicts associated with service barriers that affect outcomes, but clinicians are unable to align organizational priorities to address those barriers without the participation and support of upper management in an organization-wide strategy for realigning priorities. Therefore, a mental health agency’s capacity for identifying and addressing its misaligned priorities requires a structured, collaborative process that includes the participation of clinicians, middle management and top administration.

The Availability, Responsiveness and Continuity (ARC) Organizational Intervention

The ARC organizational intervention is designed to help service systems align priorities using a participative process that is guided by five principles of organizational effectiveness. The five ARC principles were developed specifically for mental health agencies using previous work on strategies for improving effectiveness in other types of organizations (Osborne and Gaebler, 1992). Each ARC principle describes a distinct dichotomy of conflicting priorities for mental health agencies. The ARC intervention uses the principles to guide the enactment and alignment of priorities for the agency’s improvement efforts through a structured, multi-level, team-based process that identifies and addresses service barriers associated with misaligned organizational priorities. ARC is the first intervention of this type to be designed specifically for mental health services and is more comprehensive than related models, incorporating specific intervention strategies at each stage of the intervention process (as described below under Stages) that have been developed from the broader organizational literature.

Preliminary studies show that the ARC intervention improves organizational social context and increases the effectiveness of community youth mental health and social service systems (Glisson, Dukes & Green, 2006; Glisson, Hemmelgarn et al, 2012, 2013; Glisson, Schoenwald et al, 2010). However, there is little empirical information about the active mechanisms that explain how ARC influences service outcomes. This information is important in order to understand how ARC and similar interventions can be most useful to community mental health agencies. The current study is the first to assess the alignment of organizational priorities as a mediating mechanism that links the ARC intervention to youth outcomes.

The ARC intervention aligns organizational priorities with five principles focused on client well-being:

(1) Mission-driven not rule-driven

This priority requires that all managerial and frontline service provider behavior and decisions contribute to improving the well-being of clients, and that the appropriateness of any work behavior or decision within the organization be assessed on that basis. This principle addresses the threat posed by the conflicting organizational priority of relying on overly bureaucratic processes that restrict frontline service providers’ discretion through rigid organizational rules and red tape that ignore the varying needs of individual clients and inhibit service providers’ responsiveness to unique client characteristics.

(2) Results-oriented not process-oriented

This priority requires that performance be evaluated at all levels -- the individual service provider, treatment team, program, and organization -- on the basis of improvements in the well-being of clients. This principle addresses deficits in service caused by the conflicting priority of evaluating performance on the basis of process criteria such as the number of clients served, billable service hours, or the extent to which specified bureaucratic procedures (e.g., correct completion of paperwork) are followed.

(3) Improvement-directed not status quo-directed

This priority requires that the organization’s top leadership, middle managers and clinicians continually seek more effective ways to improve the well-being of clients and avoid complacency with the status quo. This principle addresses the conflicting priority represented by the tendency of individuals in formal organizations at all levels to resist change and cling to established protocols, whether or not the existing protocols promote improvements in the well-being of clients.

(4) Relationship-centered not individual-centered

This priority requires that the identification and removal of service barriers focus on the characteristics of the social systems within which services are provided and within which clients function, rather than on individuals. Successful mental health services are supported by a network of service provider relationships, and positive change in client well-being is supported by an associated network of relationships (e.g., family, school, community). This principle addresses the conflicting priority of attributing poor services or outcomes to specific individuals rather than to failures in the service system.

(5) Participation-based not authority-based

This priority requires the active, open, and collaborative participation of clinicians, middle managers and top administrators within an agency to identify and address service barriers. Collaborative participation improves the organization’s absorptive capacity for new knowledge, openness to change, and sustainment of the improvements that are implemented. This principle counters the conflicting priority of administrators prescribing innovations to improve services in a top-down manner without the benefit of the experience, knowledge, and input of frontline service providers.

Stages in the ARC Intervention

The ARC intervention supports a mental health agency’s enactment of the five priorities using The ARC Team Leader Guide and ARC Team Member Handbook. ARC provides the structure and processes for each organization to identify and address the unique service barriers they face. Consistent with the multi-component and phased nature of successful organizational change strategies developed from organizational intervention research, trained ARC specialists facilitate an agency’s movement through three stages (i.e., collaboration, participation and innovation) to align organizational policies and practices with the five priorities (Robertson et al., 1993; Worren et al., 1999). As shown below, each stage incorporates intervention strategies developed from the organizational research literature cited for that stage. The service barriers associated with misaligned priorities are identified in the third (innovation) stage by ARC teams of clinicians who refer proposals to a multi-level Organization Action Team (OAT) for aligning priorities as specified in the five principles.

First, in the collaboration stage, the ARC specialists focus on communicating to clinicians, middle managers and top administrators the five principles described above and setting high standards for enacting the five recommended priorities. Initial work includes forming a multi-level Organizational Action Team (OAT) that includes clinicians, middle managers and top administrators to support and guide collaborative efforts focused on realigning priorities (Edmondson, Bohmer, & Pisano, 2001; Gustafson et al., 2003).

Second, in the participation stage, the ARC specialists focus on building team work and openness to change within the newly formed OAT and the ARC teams. ARC teams are formed from existing treatment teams and employ ARC tools and processes to facilitate participation, information sharing, and support among service providers. ARC treatment team supervisors are trained by ARC specialists to help team members apply the ARC principles in identifying service barriers created by misaligned priorities. Each team is guided through a series of steps designed to build the structure and social support for participative decision-making and problem-solving required for aligning priorities (Baer & Frese, 2003; Denis, Hebert, Langley, Lozeau, & Trottier, 2002; Edmondson et al., 2001; Ensley & Pearce, 2001; Rentsch & Klimoski, 2001).

Third, in the innovation stage, the ARC teams identify service barriers (e.g., inappropriate referral procedures, unnecessary red tape, process-oriented evaluative criteria) using information from frontline service providers whose efforts are guided by the five principles. ARC teams work with the OAT to enact practices, protocols and organizational procedures that reflect the desired priorities. This process ensures that recommended service improvements originate from treatment teams and that ARC principles are applied to address service barriers identified by the teams (Lemieux-Charles et al., 2002: Shortell, Bennett, & Byck, 1998).

Hypotheses

This randomized trial tests two hypotheses regarding the effects of a three year ARC intervention on the outcomes of mental health services in 14 community mental health agencies in a major Midwestern city: (1) The reduction in the psychosocial problems of youth served by agencies that complete the ARC intervention will be greater than those of youth served by agencies assigned to the control condition; (2) the effects of the ARC intervention on youth outcomes will be mediated by the agencies’ enactment of organizational priorities described by the five ARC principles.

Method

Participants

Community mental health agencies

Fourteen outpatient mental health agencies that serve youth in a large Midwestern metropolis were randomly assigned to ARC or control conditions after being matched on size (number of staff and budget). The agencies were selected to reflect characteristics of a national representative sample of mental health agencies that serve youth (e.g., Schoenwald, Chapman, Kelleher et al., 2008). Each agency had one or more units that delivered mental health treatment to youth with 15 or more staff. Agencies were excluded from the study if they had initiated the adoption of new treatment programs in the prior 12 months or if they were part of a federally-funded mental health services research network. Consistent with the national sample, selected agencies delivered a variety of mental health services (e.g., pharmacotherapy, individual psychotherapy, family therapy, skills-training, therapeutic groups) in a range of settings with the specific theoretical orientation and approach for each youth determined by individual clinicians.

Clinicians

The study included 475 clinicians who provided direct services to youth and their families in participating agencies (n = 259 clinicians in ARC agencies, n = 216 clinicians in control agencies), representing an 86% participation rate (M = 34 clinicians per agency, SD = 23.88, min = 8, max = 96). Participating clinicians were predominantly female (82.1%, n = 390) and white (82.5%, n = 392) with an average of 9.14 years of experience (SD = 8.87) working in mental health settings. Most clinicians had master’s (73.7%, n = 350) or bachelor’s (19.2%, n = 91) degrees with a major in social work (38.3%, n = 182) or an allied health field such as counseling (29.9%, n = 142). Average clinician turnover was 28 percent annually at baseline and there were no examples of clinicians working under both conditions during the study. Clinicians in the ARC and control agencies did not differ on years of experience, education, gender, race, age, or staff turnover (all p’s > .05). Clinicians, caregivers, and youth provided informed consent following protocols approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and Washington University in St. Louis.

Youth

The client sample included youth (and their caregivers) who met study criteria and consented to participate. Eligible youth were identified from those referred to participating units through initial assessments conducted as part of the usual intake procedures of those units. Selection criteria included youth who: (a) were 5 to 18 years-old at intake, (b) had no siblings enrolled in the study, (c) lived with at least one parent or long-term caregiver, (d) had behavioral or mental health symptoms requiring intervention, and (e) did not exhibit symptoms of psychosis or severe developmental delays. In accordance with typical service characteristics, youth who had received previous mental health services were eligible to participate and concomitant treatments were allowed.

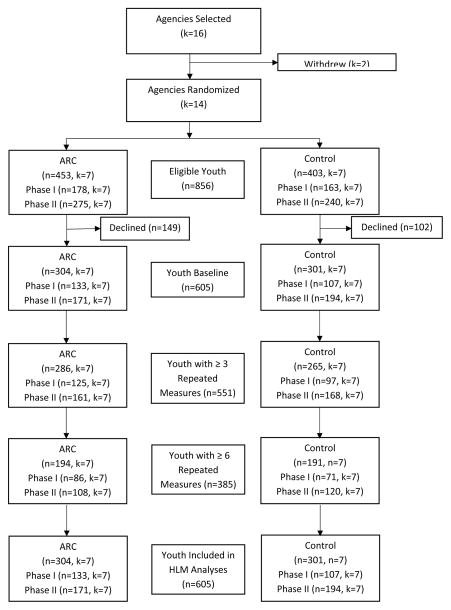

As shown in Figure 1, youth were recruited in two study phases of 24 months each. In Phase I, youth were recruited in the first 24 months (first two stages) of the ARC intervention. In Phase II, youth were recruited in the last 12 months (final stage) of the ARC intervention and the 12 months following the completion of the intervention. A total of 605 eligible youth (and their caregivers) agreed to participate (n = 240 youth during Phase I, n = 365 youth during Phase II), representing 65% of youth identified at intake. Youth participants were most often male (54.0%, n = 327) and identified as white (65.8%, n = 398) or African American (25.5%, n = 154) with an average age of 11.94 years (SD = 3.41). Consistent with other clinically referred populations, the youths’ average impairment in psychosocial functioning at baseline as assessed by the Shortform Assessment for Children (SAC) was above the clinical cut point of 25 (M = 37.82, SD = 15.36) substantiating the need for mental health treatment. Youth served by agencies in the ARC and control conditions did not differ in either phase on baseline SAC Total Problem score, age, gender, or race (all p’s > .05).

Figure 1.

Timeline showing study phases and ARC stages

Measures

Shortform Assessment for Children (SAC)

Youth outcomes were assessed as improvement in psychosocial functioning using the 48-item caregiver-report SAC that was developed with NIMH funding to assess psychosocial functioning for both white and African American youth between the ages of 5 to 18 years of age. The SAC has produced reliable and valid scores and demonstrated sensitivity to change among five unique samples of youth (n’s = 188, 393, 1249, 1254, 3790) receiving mental health or social services (Glisson & Green, 2006; Glisson, Hemmelgarn, & Post, 2002; Glisson et al., 2013; Hemmelgarn, Glisson, & Sharp, 2003; Tyson & Glisson, 2005).

Items on the SAC refer to youths’ internalizing behaviors (e.g., anxious, withdrawn) and externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggressive, noncompliant) and caregivers indicate the extent to which the youth has exhibited these problems using a 3-point rating scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 2 (Often). Item responses are summed to produce a SAC Total Problem Score where higher scores indicate greater impairment with a clinical cut score of 25. Previous validity data from the five unique samples confirm the SAC factor structure (Glisson, Hemmelgarn & Post, 2002; Tyson & Glisson, 2005) and the association of SAC Total Problem Scores with the Columbia Impairment Scale (r = .77 and 83% clinical classification agreement) (Glisson & Green, 2006), DSM IV diagnoses of depression/anxiety (r = .37) and impulsive/disruptive (r= .38) disorders (Hemmelgarn, Glisson & Sharp, 2003), CBCL Total Problem Score (r = .70) (Tyson & Glisson, 2005) and several other behavioral criteria (Glisson & Green, 2006; Glisson, Hemmelgarn, & Post, 2002; Hemmelgarn, Glisson, & Sharp, 2003; Tyson & Glisson, 2005). Alpha reliability for the SAC in the present study ranged from α = 0.92 to α = 0.95 across baseline and six waves of data collection at one month intervals.

ARC Principles Questionnaire

The agency-level enactment of ARC principles was assessed at the end of the ARC intervention using the ARC Principles Questionnaire (APQ). The APQ was developed and validated in two prior RCTs of ARC in which it demonstrated reliability, sensitivity to change, and discriminant validity with respect to agencies in ARC and control conditions (Glisson et al., 2010; Glisson et al., 2013). Items on the APQ refer to the organization’s enactment of ARC principles (e.g., improvement-directed, participation-based, relationship-centered) as described above and to the completion of planned ARC activities (e.g., completion of meetings for service improvement efforts) with items such as “Our program makes changes to be more effective in serving clients,” and “All service team members participate in decisions to improve services.” Items are accompanied by a 5-point rating scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always) with an alpha reliability of α = 0.75.

The APQ uses clinician responses to assess an organization’s efforts in enacting priorities that reflect ARC principles. Although the specific content of these efforts vary across organizations, ARC provides the structure and process for clinicians, guided by the ARC principles, to identify and address the unique service barriers in their own work environments. Clinicians’ responses to the APQ items are aggregated to the agency level based on a referent-shift composition model (Chan, 1998). Validity evidence to support aggregation is provided by sufficient within-unit inter-rater agreement based on the rwg(j) statistic (James, Demaree, & Wolf, 1993). In the present study, rwg(j) values for the APQ exceeded the recommended cutoff of .7 for all agencies (M rwg(j) = .94, min = .89, max = .97), supporting the agency-level aggregation of clinicians’ APQ responses (LeBreton & Senter, 2008). In the present sample, responses to the APQ vary between organizations (ICC = .09, χ2 = 33.66, p < ,002), discriminate between ARC and control conditions (r = .59) at the agency level, and predict the trend in youth outcomes associated with each agency (r =.58).

Control variables

Agency- and youth-level covariates were included in the analyses to optimize statistical power, control for organizational and workforce differences, and adjust SAC Total Problem Scores for youth characteristics. Agency-level covariates included baseline organizational social context (i.e., culture and climate) and workforce characteristics (i.e., clinicians’ average years of experience and education) that are associated with service capacity. Youth-level covariates include youth age and gender.

Agencies’ baseline organizational social contexts were assessed using OSC profile scores that include all six dimensions of organizational culture (proficiency, rigidity, and resistance) and climate (engagement, functionality, and stress) included in the Organizational Social Context (OSC) measure (Glisson, Landsverk et al., 2008; Williams & Glisson, 2014). OSC profile scores represent a configural approach to characterizing organizational social context in reference to three latent sub-population profiles derived empirically from a national sample of youth mental health service agencies (Schulte, Ostroff, Shmulyian, & Kinicki, 2009). The criterion and predictive validity of OSC profile scores were confirmed in two samples of youth mental health agencies on three separate outcome criteria including clinicians’ work attitudes (Glisson et al., 2014), auditor-rated mental health service quality (Olin et al., 2014), and parent-rated youth outcomes (Glisson et al., 2013).

Baseline OSC profile scores are derived using procedures described by Glisson, Williams, et al. (2014). Following the aggregation of clinicians’ responses to the six dimensions of organizational culture and climate assessed by the OSC, confirmatory latent profile analysis (Vermunt & Magidson, 2002) estimates the probability that each agency is a member of three sub-populations characterized by different OSC profiles in the national sample (Glisson, Landsverk et al., 2008). Agencies’ probabilities of membership in each of the three groups is transformed into a weighted summary score, ranging from 1.00 to 3.00, with higher scores representing more positive profiles (i.e., associated with higher service quality, increased clinician job satisfaction and commitment, and improved youth outcomes). In the present study, agencies’ baseline OSC profile scores for Phase I ranged from 1.00 to 3.00 with a mean of 1.70 (SD = .72); baseline scores for Phase II ranged from 1.04 to 2.99 with a mean of 1.77 (SD = .66).

Procedures

Study phases

Following the random assignment of agencies to ARC and control conditions, recruitment of youth for assessing service outcomes occurred in two phases, each 24 months long. As shown in Figure 1, Phase I of the study corresponded to ARC’s initial 24-month start-up period during which agencies completed the collaboration and participation stages of the ARC intervention as described above. Phase II of the study incorporated the final 12 months of the ARC intervention, referred to as the innovation stage, as well as an additional 12-month follow-up period of continued youth recruitment following the completion of ARC. During Phase I, agencies established the foundation necessary to enact the ARC principles by receiving training in the ARC process and by developing the relationships, structures, and procedures necessary to identify service barriers. According to ARC’s program theory, completion of the first two stages of the ARC intervention is necessary before agencies can effectively address service barriers by enacting ARC principles in the third stage. Agencies completed ARC’s third and final intervention stage, innovation, in Phase II.

Hypothesis 1 stated that ARC’s effects on youth outcomes should be observed during Phase II when agencies completed the third and final ARC stage. Hypothesis 2 stated that ARC’s effects on youth outcomes would be mediated by the agencies’ level of enactment of the ARC principles at the conclusion of the ARC intervention. Youth in the ARC and control groups did not differ on baseline SAC or other demographic characteristics (all p’s > .05) in either Phase I or Phase II of the study.

Intervention conditions

The ARC organizational intervention was facilitated by trained ARC specialists during a 36-month period from 2010 to 2013. The procedures used to train the ARC specialists and the ARC manuals used to guide the intervention process were previously validated in three prior randomized controlled trials of the ARC intervention (Glisson et al., 2006; Glisson et al., 2010; Glisson et al., 2013). ARC specialists facilitated the intervention using separate ARC manuals for team leaders and team members. These manuals guided completion of the ARC components in the three stages to enact the five ARC principles. Specialists had advanced graduate degrees and five or more years of experience working with human service organizations. Training for ARC specialists included reading ARC manuals and facilitation guides, didactic training sessions, and weekly consultation and supervision with developers of the ARC intervention. Detailed specification of the ARC components, stages, and principles is available in manuals published by the University of Tennessee Children’s Mental Health Services Research Center (www.cmhsrc.utk.edu).

Agencies in the control condition received no intervention. Following completion of data collection for the study, CEOs in the control group were offered a 3-day leadership institute in which they received feedback on their agencies’ organizational culture and climate profiles along with consultation on the enactment of ARC principles to improve service effectiveness in their organizations.

Clinician surveys

Trained research assistants administered the OSC and APQ surveys to clinicians at three time points corresponding to the beginning of Phase I (OSC), the beginning of Phase II (OSC), and the midpoint of Phase II (APQ). The APQ assessment was timed to capture agencies’ enactment of ARC principles at the conclusion of the ARC intervention and the midpoint of youth outcome data collection in Phase II. Clinician surveys were administered in person on-site at each agency during regularly scheduled staff meetings. In order to increase the frankness of clinicians’ responses, no managers or supervisors were present during the meetings and surveys were returned directly to research assistants who were not associated with the agency. Research assistants assured clinicians that their responses were confidential and informed them that results would only be reported in aggregate form. Clinician surveys took approximately 20 minutes to complete. Clinician response rates averaged 86% across the three waves of data collection.

Youth outcome surveys

Caregiver reports of youth psychosocial functioning were obtained by researchers via monthly telephone contacts following youth and caregiver recruitment and informed consent at intake. Measures were completed at intake and six monthly intervals thereafter. Caregivers were asked to provide information on youths’ psychosocial functioning using the 48-item SAC. Calls occurred independent of treatment participation. Caregivers received incrementally larger monetary incentives (from $5 to $15 dollars) for completion of the 20-minute follow-up phone interviews. On average, caregivers completed 5.54 SACs (SD = 1.77) per youth with a response rate of 79.1% across all waves. As shown in Figure 2, over 90% of caregivers completed at least 3 SACs (91.1%, n = 551) and nearly two-thirds completed 6 SACs (63.6%, n = 385).

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram of youth participants during Phase I and II

Data Analysis

Hypothesis 1 was tested in two steps that reflect the two phases of youth recruitment. The first step examined differences in outcomes between ARC and control agencies for youth recruited during Phase I of the study in which only the initial two stages of ARC (collaboration and participation) were completed. No significant differences in the outcomes of services between ARC and control agencies were expected for youth recruited during this first phase.

ARC is based on sequenced intervention components that must be completed before the ARC principles are enacted in the third stage, so that matriculation through the intervention process over time constitutes one observable facet of fidelity. Consequently, a significant ARC effect on outcomes for youth recruited during Phase I prior to beginning the third ARC stage of innovation where priorities are realigned, would suggest that something other than the enactment of ARC principles (which occurs in stage three) accounts for ARC’s effects on youth outcomes.

The second step of the analysis examined differences in service outcomes between ARC and control agencies for youth recruited during Phase II of the study which began with the third ARC stage (i.e., innovation) and ended one year following the completion of ARC. We anticipated significantly improved outcomes in ARC agencies relative to control agencies for youth recruited in Phase II due to the enactment of the ARC principles that coincided with the innovation stage.

Hypothesis 1 incorporated 3-level mixed-effects regression models, also known as hierarchical linear models, to account for the nesting of repeated observations within youth and of youth within agencies (Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006; Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). In the analyses, youths’ Total Problem Scores were modeled at level 1 as a function of time (measured in days following intake) in a linear growth model:

| (1a) |

Youths’ baseline Total Problem Scores and growth in Total Problem Scores were modeled at level 2 as a function of youth covariates including age (AGE) and gender (FEMALE).

| (1b) |

| (1c) |

At level 3, each agency’s expected youth baseline status and average growth in SAC Total Problem scores were modeled as a function of a binary treatment variable representing assignment to the ARC condition (ARC) and agency covariates including its baseline OSC profile (OSC), agency mean clinician experience (AM_EXP), and agency mean clinician education (AM_EDUC):

| (1d) |

| (1e) |

Equation 1 estimates the effect of ARC on agencies’ average youth outcome trajectories, adjusted for youth and agency-level covariates. Preliminary analyses confirmed the presence of significant agency-level variance in youth outcomes at each wave (Mean ICC = .06, range = .05 to .07, all p’s < .001) and a significant negative linear trend in youth total problem scores over the six month assessment period (γ = −.04, SE = .003, df = 13, p < .001). The negative linear trend indicated that, on average, youths’ total problem scores decreased (i.e., functioning improved) by 7.2 points or .47 of a standard deviation during the six months of follow-up. Tests of the random effects for the youth-level covariates age and gender confirmed that the youth covariate slopes did not vary across agencies. Consequently, the coefficients for these effects were fixed in all models. All covariates, with the exception of TIME and the bivariate treatment assignment variable, ARC, were grand mean centered to facilitate interpretation of the results. Hypothesis tests for fixed effects were based on model comparisons using the likelihood ratio χ2 test (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Analyses were conducted using HLM 6 software with maximum likelihood estimation.

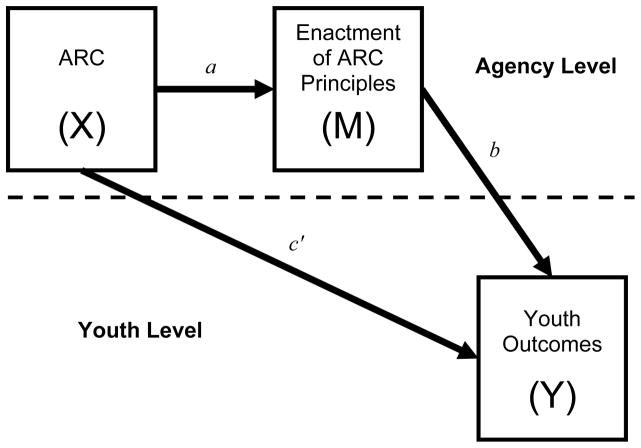

Hypothesis 2 was tested using the product of coefficients approach for multilevel mediation analysis (Krull and MacKinnon, 2001; Zhang, Zyphur & Preacher, 2009; Pituch, Murphy, & Tate, 2010). We extend Pituch et al.’s (2010) formulation to the 3-level problem with repeated measures at level 1. Under the product of coefficients approach, the point estimate of the mediated (or indirect) effect is obtained by estimating two simultaneous equations, depicted conceptually in Figure 3. These equations parse the total effect of ARC on youths’ growth in Total Problem Scores into direct (c′) and indirect (a×b) effects. In Figure 3, path a represents the agency-level effect of ARC (X) on the mediator (M), the agency-level enactment of ARC principles. Path b represents the cross-level association of ARC principles (M) with youths’ growth in Total Problem Scores (Y), adjusted for the effect of ARC. The product of the a and b coefficients (i.e., a×b) is the cross-level indirect effect of ARC and represents the expected difference in the growth in youths’ Total Problem Scores between ARC and control agencies that is attributable to the enactment of ARC principles. Path c’ in Figure 3 corresponds to the unique direct effect of ARC on youths’ growth in Total Problem Scores independent of the influence of the ARC principles. A non-significant direct effect coupled with a significant indirect effect is consistent with complete mediation and indicates that ARC’s effect on youth service outcomes is fully explained by the enactment of the ARC principles.

Figure 3.

Conceptualization of two-level mediation model

For 3-level mediation models in which the X and M variables are at the highest level (in this case, the agency), path a is estimated using a single-level ordinary least squares regression as shown in Equation 2 (MacKinnon, 2008; Pituch et al., 2010).

| (2) |

In this model, the agency-level mediator (enactment of ARC principles) is estimated as a function of agency-level treatment assignment (ARC), agency-level covariates (OSC profile, agency mean clinician experience and education), and the agency means of the youth-level covariates included in Equations 1 and 3 (i.e., age and gender). The inclusion of the agency means for the youth-level covariates is necessary to adjust the a path in a manner equivalent to the adjustment of the b path in the 3-level model predicting youths’ growth in Total Problem Scores (i.e., Equation 3). Path a is represented by the γ1 coefficient in Equation 2.

The b path is estimated using a 3-level mixed effects regression model identical to Equation 1, with two exceptions: the agency-level mediator, enactment of ARC principles represented by APQk, is added to equation 1e as a predictor at level 3 on both the intercept and slope as shown in Equations 3a and 3b:

| (3a) |

| (3b) |

Note that Equations 3a and 3b differ from Equations 1d and 1e only in the inclusion of the APQ term which represents the influence of the mediator (APQ) adjusted for the independent variable, ARC, and the agency- and youth-level covariates (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). Equation 3 estimates the b and c’ paths represented in Figure 3 via the γ105 and γ101 coefficients, respectively. The product of the a coefficient from Equation 2 and the b coefficient from Equation 3 (i.e., γ1γ105) provides an unbiased point estimate of the cross-level indirect or mediated effect of ARC on growth in youths’ Total Problem Scores through the enactment of ARC principles (Krull & MacKinnon, 2001; Pituch et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2009). Measurement of agencies’ enactment of the ARC principles was timed to occur at the end of the intervention period and one year before the end of youth recruitment for Phase II, thereby establishing temporal precedence of ARC in relation to the mediator and precedence of the mediator in relation to youth outcomes.

Two complementary approaches were used to test the statistical significance of ARC’s mediated effect on youth outcomes through the ARC principles. First, the joint significance test examined the joint null hypothesis, H0: a = 0 and b = 0 (Cohen & Cohen, 1983, p. 366; MacKinnon, Lockwood, Hoffman et al., 2002). A significant mediation effect is supported if the null hypotheses for both the a and b coefficients are rejected in their respective models. In a large simulation study comparing 14 methods for testing the statistical significance of mediation effects, MacKinnon et al. (2002) found that the joint significance test provided the best balance of Type I error rates and statistical power. Moreover, the joint significant test provides a flexible null hypothesis significance testing approach for complex mediation models such as the one described here.

Second, asymmetric 95% confidence limits were constructed around the point estimate of the indirect effect using computationally intensive Monte Carlo methods (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004; Preacher & Selig, 2012). Under the Monte Carlo approach, parameter estimates of the a and b coefficients and their standard errors are used to construct an empirical sampling distribution of the indirect effect. The population value of the indirect effect is inferred to be nonzero if the 95% confidence limits of the empirical sampling distribution do not span zero (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Confidence limits based on computationally intensive resampling methods are more accurate and exhibit higher statistical power than normal theory approaches (e.g., the Sobel test) because the sampling distributions of indirect effects rarely conform to normality (MacKinnon et al., 2004). Based on extensive simulation research, several methodologists have recommended Monte Carlo CIs as the optimal choice to maximize statistical power and avoid Type I errors (Biesanz et al., 2010; Hayes & Scharkow, 2013; MacKinnon et al., 2004), particularly for multilevel mediation models where alternative resampling strategies such as bootstrapping are not well-developed (Preacher & Selig, 2012). The online R utility developed by Selig and Preacher (2008) was used to construct the Monte Carlo CIs for the indirect effects in this study using 100,000 replications. The mediated effect is a fixed effect because both the independent variable (X) and the mediator (M) are at the highest level of the model, so the a and b paths cannot incorporate random effects.

Results

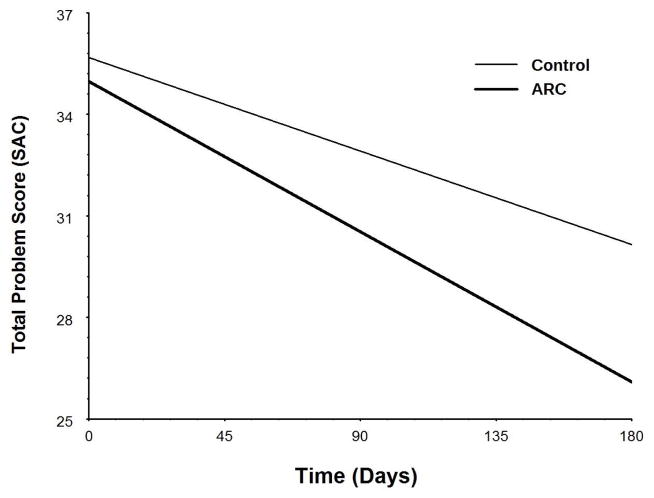

Table 1 presents results of the three, 3-level, mixed effects regression analyses examining youth outcomes in ARC versus control agencies during study Phases I and II, respectively (coded as ARC = 1, control = 0). Consistent with Hypothesis 1, youth outcomes did not differ between ARC and control agencies during Phase I as indicated by the nonsignificant ARC x Time interaction (γ = .003, SE = .009, p > .500), but were significantly improved in ARC agencies relative to control during Phase II (γ = −.019, SE = .009, p = .045). As shown in Figure 4, the significant ARC x Time interaction in Phase II indicates that the rate of improvement in youths’ Total Problem scores for ARC agencies was 1.6 times the rate of improvement in control agencies. This translates into a difference in the rate of change in SAC scores of .57 points per month between ARC and control conditions and a standardized difference in group means of d = .23 at the end of the six month follow-up period. The expected Total Problem Score for youth in control agencies remained significantly above the clinical cut point of 25 after six months (γ = 30.11, t = 4.79, df = 193, p < .001), while the expected Total Problem Score for youth in ARC agencies did not (γ = 26.69, t = 1.44, df = 170, p = .153). The non-significant effect of ARC during Phase I of the study coupled with the significant effect of ARC during Phase II of the study supports Hypothesis 1 and suggests that the ARC intervention improved youth outcomes.

Table 1.

Three-level mixed effects regression analyses of youth SAC Total Problem Scores.

| Phase I

|

Phase II

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE |

| Fixed Effects | ||||||

| Intercept | 39.440*** | 2.257 | 35.686*** | 1.286 | 35.009*** | 1.370 |

| OSC profile | .455 | 2.646 | −1.107 | 1.701 | −.185 | 1.750 |

| Ave. clinician experience | −.695 | .466 | −.592 | .314 | −.563 | .289 |

| Ave. clinician education | 6.006 | 7.584 | 3.936 | 4.464 | 3.107 | 4.017 |

| ARC (ARC=1, control=0) | −2.624 | 3.194 | −.709 | 1.975 | .747 | 2.373 |

| Youth age | .364 | .338 | .463 | .243 | .504* | .249 |

| Youth gender | −1.218 | 1.951 | 2.415 | 1.574 | 2.333 | 1.578 |

| Time (days from intake) | −.033** | .007 | −.031*** | .006 | −.040*** | .007 |

| Time x Baseline OSC profile | .000 | .009 | .007 | .008 | .017 | .009 |

| Time x Ave. clinician experience | .000 | .001 | −.001 | .002 | −.001 | .001 |

| Time x Ave. clinician education | .032 | .023 | .012 | .022 | .006 | .021 |

| Time x Youth age | −.000 | .001 | −.001 | .001 | −.001 | .001 |

| Time x Youth gender | −.007 | .009 | −.006 | .008 | −.007 | .008 |

| Time x ARC | .003 | .009 | −.019* | .009 | −.000 | .011 |

| ARC Principles | −4.536 | 5.379 | ||||

| Time x ARC Principles | −.061* | .026 | ||||

| Variance Components | ||||||

| Within youth | 37.433 | 41.379 | 41.362 | |||

| Youth intercepts | 184.345 | 191.938 | 193.371 | |||

| Youth slopes | .002 | .003 | .003 | |||

| Agency intercepts | 14.799 | 2.849 | .723 | |||

| Agency slopes | .000 | .000 | .000 | |||

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Figure 4.

Three-level hierarchical linear models analysis of trends in youth total problem scores in ARC and control conditions

Hypothesis 2 stated that the agency-level enactment of ARC principles would mediate ARC’s effects on youth outcomes. The third column of coefficients in Table 1 presents results of the mixed effects regression analysis testing path b for Hypothesis 2. Consistent with a mediation effect, increased enactment of ARC principles significantly improved youth outcomes (γ = −.061, SE = .026, p = .020) and the direct effect of ARC (cγ) was no longer significant after controlling for the enactment of ARC principles (γ = .000, SE = .011, p = .981). Furthermore, results from the ordinary least squares regression analysis testing path a of the indirect effect indicated that ARC agencies exhibited higher enactment of ARC principles relative to control agencies (B = .292, SE = .117, p = .042, ΔR2 = .21), after controlling for baseline OSC, workforce characteristics, and youth characteristics (ARC also significantly increased the enactment of ARC principles in the absence of all covariates). The resulting indirect effect of ARC on youth outcomes through ARC principles was statistically significant according to the joint significance test and according to the asymmetric 95% Monte Carlo confidence intervals (a×b = −.018, 95% CI: LL = −.043, UL = −.001). These results support Hypothesis 2 and indicate that ARC’s effects on youth outcomes were fully mediated by the enactment of priorities specified in the ARC principles. The standardized difference in youths’ Total Problem Scores attributable to ARC through the enactment of ARC principles was d = .21.

An additional multilevel, mixed effects logistic regression analysis of reliable change index scores (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) for the individual youth clustered within organizations confirmed the effect of ARC on youth outcomes. Controlling for the same covariates included in the model described above, Phase II youth served by agencies in the ARC condition were more likely to meet the criteria for reliable change (RCI = 12.04) than were youth served by agencies in the control condition (43.05 % vs 22.21 %, γ = .973, SE = .235, p < .000). Moreover, the enactment of ARC principles explained significant variance in reliable change (γ = 1.346, SE = .530, p < .011) when added to the logistic model (path b in Figure 3), producing a significant indirect effect of ARC on reliable change in youth outcomes (a×b = .393) according to the asymmetric 95% Monte Carlo confidence intervals (, 95% CI: LL = .035, UL = .919) and the joint significance test.

Discussion

The outcomes of community-based youth mental health services have been described as the product of a multi-layered mental health ecosystem that includes the referred youth, families, practitioners, organizations providing the treatment, network of service systems, and policy context (Weisz, Ugueto, Cheron et al, 2013). This perspective suggests that research on strategies for improving community based services must be broadened beyond the use of EBPs and that the focus on EBPs may be missing important information from other levels of the ecosystem for improving services. Similarly, Kazdin’s (2015) review of treatment as usual (TAU) in research and practice identifies the type of setting and other factors that influence treatment outcomes and concludes that future research on improving community based services should examine a variety of factors and strategies for improving the outcomes of usual treatments (TAU) as well as EBPs. The present study responds to the need for a broader perspective on improving community-based mental health services by examining the effects of an organizational strategy that has been shown in preliminary studies to improve service outcomes both with and without the implementation of an EBP (Glisson, Hemmelgarn et al, 2013; Glisson, Schoenwald et al, 2010).

The present findings provide evidence that the outcomes of community-based youth mental health services are affected by the priorities of the organizational context that provides the services and that organizational intervention strategies can be used to improve service outcomes by altering and aligning those priorities (Zohar & Hoffman, 2012). Community mental health service agencies enact priorities in responding to competing demands for generating revenue, serving target populations, and managing work activities within and across organizational levels (Weisz, Ugueto, Cheron et al, 2013). We conclude that misaligned priorities from competing demands (e.g., the demand for increased client headcounts versus the demand for quality service), the failure to enact espoused priorities focused on improving client well-being, and inconsistent priorities that create opposing efforts (e.g., limiting clinician authority while requiring clinical discretion) reduce effectiveness.

The findings show that mental health service organizations can improve service outcomes by using a cross-level, collaborative, participative process to enact consistent priorities that are aligned with five principles of effective service organizations. The five principles address, for example, service deficits created by organizations emphasizing control of work behavior through bureaucratic rules and red tape, focusing on headcounts and billable hours rather than quality care, making top-down decisions that affect services without input from service providers, blaming individuals for poor service system outcomes rather than identifying service system weaknesses, and resisting improvement efforts without questioning deficits in the status quo.

The present study is the first to examine the enactment of consistent organizational priorities that are aligned with principles of effective service delivery as a mechanism that links an organizational intervention to mental health service outcomes. The organizations’ relative success in enacting ARC priorities fully mediated the ARC intervention effect on service outcomes. The fact that the three constructs were operationalized, respectively, as a randomly assigned variable (i.e., ARC intervention), perceptions shared by clinicians who provide services in the same organization (i.e., enacted priorities), and youth caregiver reports (i.e., youth outcomes) eliminates concerns about common method error variance and strengthens support for the role of organizational priorities in effective care.

Preliminary studies show that the ARC organizational intervention can improve youth mental health service outcomes with or without the implementation of a specific EBP (Glisson, Hemmelgarn et al, 2013; Glisson, Schoenwald et al, 2010). Those results along with the current finding that improvements in service outcomes are a function of realigned organizational priorities suggest the need for additional research that couples strategies for changing organizational priorities with other strategies for improving service outcomes such as the implementation of EBPs. The two organizational priorities that are focused on the value of being results-oriented and improvement-directed, respectively, directly support the adoption of EBPs and along with the other three priorities (i.e., mission-driven, participation-based, relationship-centered) complement the organizational processes required for successful EBP adoption, implementation and sustainment. This suggests the need for research on improving the effectiveness of community mental health systems that couples efficacious treatments or other best practices (e.g., the use of feedback systems) with strategies for enacting organizational priorities that support their use.

Research on factors and strategies in the youth mental health ecosystem may ultimately lead us to conclude that the relative importance of factors at various levels (e.g., practitioner, organization, policy context) may vary and interrelate across client populations and service systems (Aarons, Glisson, Green et al, 2012). Future research could find that practice and treatment factors are relatively more important for some populations and settings and organizational factors may be relatively more important for others, but the objective of the current study is not to partition the variance in youth outcomes between treatment and organizational factors. Rather, the objective is to illustrate the importance of organizational factors in the community based youth mental health ecosystem and offer evidence of one promising approach for improving outcomes with organizational strategies. Future studies are planned to link specific organizational priority problems to the service barriers that are identified and addressed by clinicians in each organization as a next step in the development of the ARC intervention. We also expect that future studies will contribute to a more precise delineation of the relative contributions of practitioner, organization, policy and other components of the community-based youth mental health ecosystem along with the relative impact of improvement strategies that focus on each.

Caveats

Several caveats must be considered in interpreting these results. First, the youth were randomized as clusters served by agencies that were randomly assigned to ARC and control conditions after matching on agency size. Cluster randomization is a well-accepted strategy, youth gender and age were included as covariates, and youth in the two conditions did not differ in outcomes in Phase I of the study or on intake measures at baseline in either Phase I or II. These characteristics of the design support the causal attributions of our mediation model. Nevertheless, it is possible that other unmeasured youth level variables could explain outcomes in Phase II in a way that limits internal validity.

Second, the assessment of priorities enacted within each organization depended on the report of clinicians in each agency. Although the level of agreement among clinicians within each organization was assessed and showed that clinicians within the same organization shared similar views of their organization’s priorities, and that those views were associated with youth outcomes, clinician views could be affected by demand characteristics or might not coincide with other measures of enacted organizational priorities (such as CEO reports). Subsequent studies could be designed to explore the unique ways that each of the five principles is expressed and addressed by individual organizations.

Third, a majority of the youth received six monthly assessments (64%) and almost all youth received at least three monthly assessments (91%), but missing data could have altered estimations of youth outcomes. While these caveats temper interpretation, the random assignment of agencies to conditions, the differences in ARC effects on youth outcomes in Phases I (not significant) and II (significant), and the relative time points at which the measures of the agencies’ enacted priorities and youth outcomes were collected support the conclusion of a positive ARC effect on youth outcomes that is mediated by the priorities described in the five ARC principles.

Finally, the current study examines 14 organizations in a single, large mid-western metropolitan area in a four year period which controls the policy context of the agencies associated with geographical location and time but limits the external validity of the findings. Although characteristics of the organizations are similar to those of a nationwide sample of community-based organizations providing mental health services to youth, the sampled organizations were not randomly selected and the extent to which they are representative of agencies that serve youth nationwide is unknown. Replication of the study in other geographical locations would increase the generalizability of our findings and support efforts to improve our understanding of organizational factors in the improvement of community-based mental health services.

Public Health Significance Statement.

The ARC intervention improves the outcomes of community based mental health services for youth. ARC improves outcomes by aligning organizational priorities with five principles of effective service.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH R01-MH084855 (PI:CG) and F31-MH099846 (PI:NJW).

Contributor Information

Charles Glisson, University of Tennessee

Nathaniel J. Williams, Boise State University

Anthony Hemmelgarn, University of Tennessee

Enola Procter, Washington University St. Louis

Philip Green, University of Tennessee

References

- Aarons G, Glisson C, Green P, Hoagwood K, Kelleher K, Landsver J. The organizational social context of mental health services and clinician attitudes toward evidence-based practice: A United States national study. Implementation Science. 2012;7:56. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Argyris C, Schon DA. Organizational Learning: Theory, Method and Practice. 2. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Baer M, Frese M. Innovation is not enough: Climates for initiatives and psychological safety, process innovations and firm performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2003;24:45–68. [Google Scholar]

- Biesanz JC, Falk CF, Savalei V. Assessing mediational models: Testing and interval estimation for indirect effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2010;45:661–701. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2010.498292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickman L. A continuum of care: More is not always better. American Psychologist. 1996;51:689–701. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.51.7.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan D. Functional relations among constructs in the same content domain at different levels of analysis: A typology of composition models. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1998;83:234–246. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P. Applied multiple regression/ correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Denis JL, Hebert Y, Langley A, Lozeau D, Trottier LH. Explaining diffusion patterns for complex health care innovations. Health Care Management Review. 2002;27:60–73. doi: 10.1097/00004010-200207000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson AC, Bohmer RM, Pisano GP. Disrupted routines: Team learning and new technology implementation on hospitals. Administrative Science Quarterly. 2001;46:685–716. [Google Scholar]

- Ensley MD, Pearce CL. Shared cognition in top management teams: Implications for new venture performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2001;22:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Garland AF, Haine-Schlagel R, Brookman-Frazee L, Baker-Ericzen M, Trask E, Fawley-King K. Improving community-based mental health care for children: Translating knowledge into action. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2013;40:6–22. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0450-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Dukes D, Green P. The effects of the ARC organizational intervention on caseworker turnover, climate, and culture in children’s service systems. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2006;30:855–880. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Atkinson S, Williams NJ. Randomized trial of the availability, responsiveness and continuity (ARC) organizational intervention with community mental health programs and clinicians serving youth. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2012;51:780–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Williams NJ. Randomized trial of the availability, responsiveness and continuity (ARC) organizational intervention for improving youth outcomes in community mental health programs. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:493–500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Hemmelgarn AL, Post JA. The Shortform Assessment for Children: An assessment and outcome measure for child welfare and juvenile justice. Research on Social Work Practice. 2002;12:82–106. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Green P. Role of specialty mental health care in predicting child welfare and juvenile justice out-of-home care. Research on Social Work Practice. 2006;16(5):480–490. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Mayberg S, Green P The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2008;35:98–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Schoenwald SK, Hemmelgarn A, Green P, Dukes D, Armstrong KS, Chapman JE. Randomized trial of MST and ARC in a two-level evidence-based treatment implementation strategy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:537–550. doi: 10.1037/a0019160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Williams NJ, Green P, Hemmelgarn A, Hoagwood K. The organizational social context of mental health Medicaid waiver programs with family support services: Implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2014;41:32–42. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0517-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson DH, Sainfort F, Eichler M, Adams L, Bisognano M, Steudel H. Developing and testing a model to predict outcomes of organizational change. Health Services Research. 2003;38:751–776. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, Scharkow M. The relative trustworthiness of inferential tests of the indirect effect in statistical mediation analysis: Does method really matter? Psychological Science. 2013;24:1918–1927. doi: 10.1177/0956797613480187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal data analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmelgarn AL, Glisson C, Sharp SR. The validity of the Short-form Assessment for Children (SAC) Research on Social Work Practice. 2003;13:510–530. [Google Scholar]

- James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G. Rwg: An assessment of within-group agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78:306–309. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Truax P. Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE. Treatment as usual and routine care in research and clinical practice. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015;42:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krull JL, MacKinnon DP. Multilevel modeling of individual and group level mediated effects. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2001;36:249–277. doi: 10.1207/S15327906MBR3602_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBreton JM, Senter JL. Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods. 2008;11:815–852. [Google Scholar]

- Lemieux-Charles L, Murray M, Baker GR, Barnsley J, Tasa K, Ibrahim SA. The effects of quality improvement practices on team effectiveness: a meditational model. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2002;23:553–553. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Hoffman JM, West SG, Sheets V. A comparison of methods to test mediation and other intervening variable effects. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:83–104. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.7.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMorrow S, Howell E. State Mental Health Systems for Children: A Review of the Literature and Available Data Sources. Washington, DC: Urban Institute; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. Strategic Plan for Research. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 2015. NIH Publication Number 15–6368. [Google Scholar]

- Olin SS, Williams N, Pollock M, Armusewicz K, Kutash K, Glisson C, Hoagwood KE. Quality indicators for family support services and their relationship to organizational social context. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2014;41:43–54. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0499-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne D, Gaebler TA. Reinventing Government. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pate-Cornell ME. Organizational aspects of engineering system safety: The case of offshore platforms. Science. 1990;250:1210–1217. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4985.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Weiss HA, Chowdhary N, Naik S, Pednekar S, Chatterjee S, Kirkwood BR. Lay health worker led intervention for depressive and anxiety disorders in India: Impact on clinical and disability outcomes over 12 months. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;199:459–466. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pituch KA, Murphy DL, Tate RL. Three-level models for indirect effects in school- and class-randomized experiments in education. Journal of Experimental Education. 2010;78:60–95. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2004;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Selig JP. Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Communication Methods and Measures. 2012;6:77–98. [Google Scholar]

- Quinn RE, Rohrbaugh J. A spatial model of effectiveness criteria: Towards a competing values approach to organizational analysis. Management Science. 1983;29:363–377. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis. 2. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rentsch JR, Klimoski RJ. Why do “great minds” think alike? Antecedents of team member schema agreement. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2001;22:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson PJ, Roberts DR, Porras JI. Dynamics of planned organizational change: Assessing empirical support for a theoretical model. Academy of Management Journal. 1993;36:619–634. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5. New York: Free Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider B, Bowen D. Winning the service game. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Chapman JE, Kelleher K, Hoagwood KE, Landsverk J, Stevens J, Glisson C, Rolls-Reutz J The Research Network on Youth Mental Health. A survey of the infrastructure for children’s mental health services: Implications for the implementation of empirically supported treatments (ESTs) Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2008;35:84–97. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte M, Ostroff C, Shmulyian S, Kinicki A. Organizational climate configurations: Relationships to collective attitudes, customer satisfaction, and financial performance. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2009;94:618–634. doi: 10.1037/a0014365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selig JP, Preacher KJ. Monte Carlo method for assessing mediation: An interactive tool for creating confidence intervals for indirect effects [Computer software] 2008 Jun; Available from http://quantpsy.org/

- Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: What it will take to accelerate progress. The Milbank Quarterly. 1998;76:593–624. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.00107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons T. Behavioral integrity: The perceived alignment between managers’ words and deeds as a research focus. Organization Science. 2002;13:18–35. [Google Scholar]

- Tyson EH, Glisson C. A cross-ethnic validity study of the short-form assessment for children (SAC) Research on Social Work Practice. 2005;15:97–109. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt JK, Magidson J. Latent class cluster analysis. In: Hagenaars JA, McCutcheon AL, editors. Applied latent class analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2002. pp. 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Warren JS, Nelson PL, Mondragon SA, Baldwin SA, Burlingame GM. Youth psychotherapy change trajectories and outcomes in usual care: Community mental health versus managed care settings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:144–155. doi: 10.1037/a0018544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weick KE. The Social Psychology of Organizing. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Doss AJ, Hawley KM. Youth psychotherapy outcome research: A review and critique of the evidence base. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:337–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Donenberg GR, Han SS, Weiss B. Bridging the gap between laboratory and clinic in child and adolescent psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995;63:688–701. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.5.688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Krumholz LS, Santucci L, Thomassin K, Ng MY. Shrinking the gap between Research and Practice: Tailoring and testing youth psychotherapies in clinical care contexts. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2015;11:139–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032814-112820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Ugueto AM, Cheron DM, Herren J. Evidence-based youth psychotherapy in the mental health ecosystem. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42(2):274–286. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.764824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weisz JR, Weiss B, Donnberg GR. The lab vs. the clinic: Effects of child and adolescent psychotherapy. American Psychologist. 1992;47:1578–1585. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.47.12.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NJ, Glisson C. Testing a theory of organizational culture, climate, and youth outcomes in child welfare systems: A United States national study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38:757–767. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Worren NAM, Ruddle K, Moore K. From organizational development to change management: The emergence of a new profession. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 1999;35:273–286. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zyphur MJ, Preacher KJ. Testing multilevel mediation using hierarchical linear models: Problems and solutions. Organizational Research Methods. 2009;12:695–719. [Google Scholar]

- Zohar D, Hofmann DA. Organizational culture and climate. In: Kozlowski SWJ, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Organizational Psychology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]