Abstract

Objective

Failure to detect clinical deterioration in the hospital is common and associated with poor patient outcomes and increased healthcare costs. Our objective was to evaluate the feasibility and accuracy of real-time risk-stratification using the electronic Cardiac Arrest Risk Triage score version 1 (eCART), an electronic health record based early warning score.

Design

We conducted a prospective black-box validation study. Data were transmitted via HL7 feed in real-time to an integration engine and database server wherein the scores were calculated and stored without visualization for clinical providers. The high-risk threshold was set a priori. Timing and sensitivity of eCART activation were compared to standard of care Rapid Response Team (RRT) activation for patients who experienced a ward cardiac arrest or intensive care unit (ICU) transfer.

Setting

Three general care wards at an academic medical center

Patients

3,889 adult inpatients

Measurements and Main Results

The system generated 5,925 segments during 5,751 admissions. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve for eCART was 0.88 for cardiac arrest and 0.80 for ICU transfer, consistent with previously published derivation results. During the study period, 8/10 patients with a cardiac arrest had high-risk eCART scores, while the RRT was activated on 2 of these patients (p<0.05). Further, eCART identified 52% (n=201) of the ICU transfers compared to 34% (n=129) by the current system (p<0.001). Patients met the high-risk eCART threshold a median of 30 hours prior to cardiac arrest or ICU transfer versus 1.7 hours for standard RRT activation.

Conclusions

eCART identified significantly more cardiac arrests and ICU transfers than standard RRT activation and did so many hours in advance.

Keywords: Heart arrest, hospital rapid response team, decision support techniques, early diagnosis, models (statistical)

INTRODUCTION

Many patients who experience an adverse outcome on the hospital wards exhibit abnormal vital signs hours to days before the event (1–3). Unfortunately, these vital sign abnormalities often go unnoticed by hospital staff (1,2), and studies have shown that delayed intervention, such as sepsis management or ICU transfer, leads to worse outcomes (4–7). As a result, the majority of hospitals in the US have implemented Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) (8), which are specialized groups of caregivers who provide early assessment and intervention to deteriorating patients (2). However, the effectiveness of these teams remains controversial (9), and consensus statements have proposed that the inability to accurately trigger RRT activation is a major limitation (2,10,11).

A wide variety of RRT protocols exist among different hospitals, including who may initiate the call. Traditional RRT activation criteria often include triggering for any one of a pre-specified set of abnormal vital signs, but they are known to have poor accuracy for predicting adverse events (12). In our prior work, we used retrospective data to derive and validate an algorithm for determining the risk of cardiac arrest or ICU transfer, and subsequently named it the electronic Cardiac Arrest Risk Triage score version 1, (eCART) (13). In this current study, we developed a real-time analytics platform and conducted a prospective black-box study to assess the feasibility and accuracy of real-time eCART calculation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was conducted between February 4, 2013 and June 20, 2014 in three adult general care wards containing 83 beds at an urban academic medical center. All patients admitted to one of those beds during the study period were included. The hospital had a nurse-led RRT in place that could be activated by any clinical staff member, but no specific vital sign criteria were used for their activation (14). The study was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board (IRB#14-0538).

Real Time Data Collection

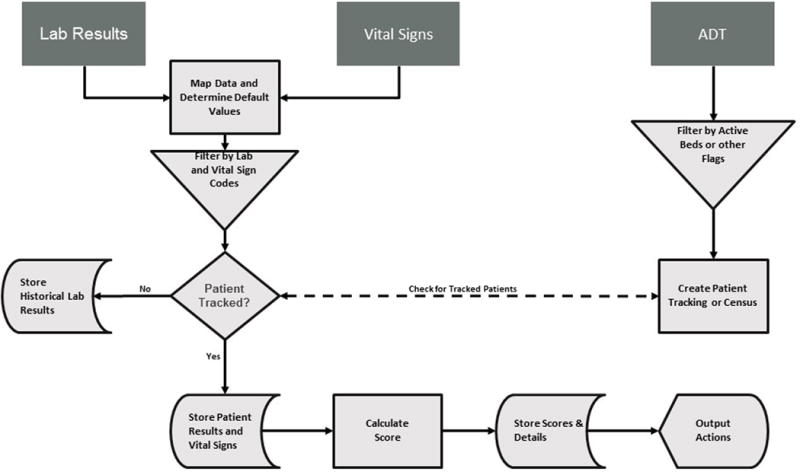

Existing hospital HL7 feeds from the laboratory information system, bedside patient monitors, and registration/ADT (admission-discharge-transfer) system were integrated into a scoring database through the integration engine. The laboratory values and vital signs were mapped and filtered according to the eCART algorithm variables. ADT information was collected to create a patient tracking data set with appropriate ward beds flagged for processing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Real Time Data Flow.

Abbreviations: ADT, admission-discharge-transfer

Values that matched the clinical data and ADT flagged ward beds were used to calculate eCART scores. All lab results were held in the database for 36 hours in case of patient admission to one of the targeted ward beds. eCART scores were calculated for a targeted patient whenever a variable was changed from previous values, regardless of the magnitude of change, utilizing database stored procedures as real-time data flowed through the system. Default median values derived from all hospitalized ward patients were stored in the database and used if a previous value for a particular variable could not be found. Final eCART scores, clinical results to calculate the scores, and additional details were stored for analytics and future output actions.

Analysis

The unit of analysis was a ward segment, defined as a consecutive period of time that a patient was hospitalized in one of the study units. Each ward segment concluded with one of three mutually exclusive outcomes: cardiac arrest, ICU transfer, or no adverse outcome. Cardiac arrest was defined, a priori, as a loss of pulse with attempted resuscitation while on the wards or within 6 hours after transfer to ICU. Time of ICU transfer was determined by the time of the last vital sign documentation on the general ward prior to transfer. All ward-to-ICU transfers were presumed to be unexpected. Patients who went to the ICU by way of an operating room were not counted as unexpected ICU transfers. Further, decisions to transfer patients to an ICU were made by the on-call Medical ICU Resident. The RRT nurses did not have direct admitting privileges. Patients who died in the study units without attempted resuscitation were presumed to have been receiving palliative care only and were excluded from analysis. Additionally, segments with at least one RRT call were identified. The dates and times for cardiac arrest, ICU transfer, and RRT activation, as well as patient characteristics were provided by the Clinical Research Data Warehouse (CRDW) maintained by the Center for Research Informatics (CRI) at University of Chicago (IRB11-0539).

Patient demographics were compared between segments that did not result in an adverse outcome and those that resulted in cardiac arrest or ICU transfer. Using the highest score in each ward segment, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for eCART predicting cardiac arrest and ICU transfer at any time during a ward segment was calculated using the trapezoidal rule (15). Scores were categorized, a priori, into risk categories by setting the high and intermediate-risk thresholds at 54 and 50, respectively, which represented the 95% and 86% specificity cut-off determined from our previous study (13). For ward segments that resulted in cardiac arrest or ICU transfer, McNemar’s test was used to compare the proportion of those segments that had at least one intermediate and/or high-risk eCART score to the proportion that had an RRT call. Times from critical eCART score or RRT call to cardiac arrest or ICU transfer were compared using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. All tests of significance used a two-sided p-value less than 0.05. Statistical analyses were completed using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

During the study period, 5,751 admissions, occurring in 3,889 distinct patients, generated 5,969 unique ward segments. We excluded 44 segments that ended in death without attempted resuscitation, leaving 5,925 segments. Demographic characteristics by ward segment are shown in Table 1. The median highest eCART score per segment was 45 [IQR 41–50] with 14% and 25% meeting the high and intermediate-risk threshold respectively. Ten ward segments ended in cardiac arrest and 383 ended in ICU transfer. Of the 836 segments that met the high-risk threshold, 209 (25%) resulted in an ICU transfer or cardiac arrest.

Table 1.

Comparisons of Characteristics Between Ward Segments Which Resulted in Cardiac Arrest, ICU Transfer, or Neither Event

| Characteristics | No Adverse Outcome (n=5,532) | ICU Transfer (n=383) | Cardiac Arrest (n=10) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 58.9±17 | 60.4±16 | 56.4±20 |

| Female Sex (%) | 2681 (48.5) | 184 (48.0) | 4 (40.0) |

| Hospital Length of Stay, median (IQR), d | 4.7 (2.4–7.0) | 13.2 (7.2–25.5) | 11.4 (10.0–36.1) |

| Survived to discharge (%) | 5506(99.5) | 268 (70.0) | 0 (0) |

| Race (%): | |||

| White | 2195 (39.7) | 137 (35.8) | 3 (30) |

| Black/African-American | 2841 (51.4) | 213 (55.6) | 4 (40) |

| Asian/Mideast Indian | 170 (3.1) | 10 (2.6) | 2 (20) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 172 (3.1) | 11 (2.9) | 1 (10) |

| Other/Unknown | 154 (2.8) | 12 (3.1) | 0 |

Abbreviations: ICU, Intensive Care Unit

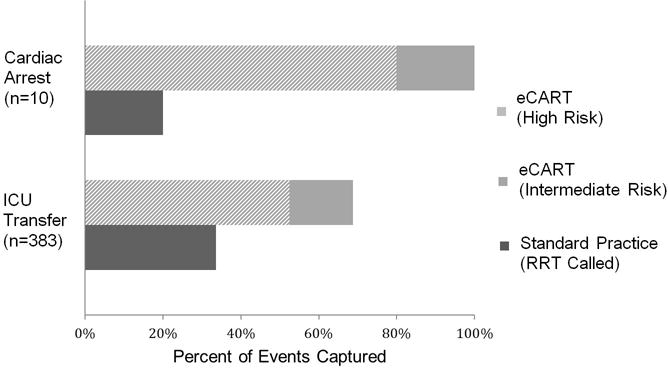

Overall, the AUC for eCART predicting cardiac arrest or ICU transfer was 0.80 [95%CI 0.78–0.82]. The AUC for predicting cardiac arrest alone was 0.88 [95%CI 0.85–0.92]. Of the 10 cardiac arrests, eCART surpassed the high-risk threshold for 8/10 of those patients and surpassed the intermediate-risk threshold for all 10 patients (Figure 2). In contrast, only two of these patients triggered an RRT (p<0.05). The AUC for eCART predicting ICU transfer alone was 0.80 [95%CI 0.77–0.82]. For patients who experienced ICU transfer, 52% surpassed the high-risk threshold and 69% surpassed the intermediate-risk threshold, compared to 34% of ICU transfer patients who triggered an RRT (p<0.001) (Figure 2). In addition, 27% of ICU transfers both triggered an RRT and surpassed the intermediate-risk threshold while 24% never activated an RRT or met the intermediate-risk threshold. The sensitivity and specificity of the high and intermediate-risk thresholds for cardiac arrest and ICU transfer are listed in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Events Identified by Standard Practice vs. eCART

Table 2.

AUC, Sensitivity and Specificity of eCART at High and Intermediate-Risk Thresholds

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | AUC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICU Transfer | 0.80 (0.77–0.82) | ||

| eCART > 54 | 52.5 (47.3–57.6) | 88.5 (87.7–89.4) | |

| eCART ≥ 50 | 68.9 (64.0–73.5) | 78.0 (76.8–79.0) | |

| Cardiac Arrest | 0.88 (0.85–0.92) | ||

| eCART > 54 | 80.0 (44.2–96.5) | 86.0 (85.1–86.9) | |

| eCART ≥ 50 | 100 (65.5–100.0) | 75.1 (73.9–76.2) |

Abbreviations: eCART, electronic cardiac arrest risk triage score; AUC, Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; ICU, Intensive Care Unit

The RRT was activated in 241 ward segments. Of those, an eCART threshold was met in 176 (73%) of RRTs, with 140 (58%) meeting both the intermediate and high-risk thresholds and an additional 36 (15%) meeting only the intermediate-risk criteria. Two segments with RRT activations (0.8%) resulted in cardiac arrest and 129 (34%) resulted in ICU transfer.

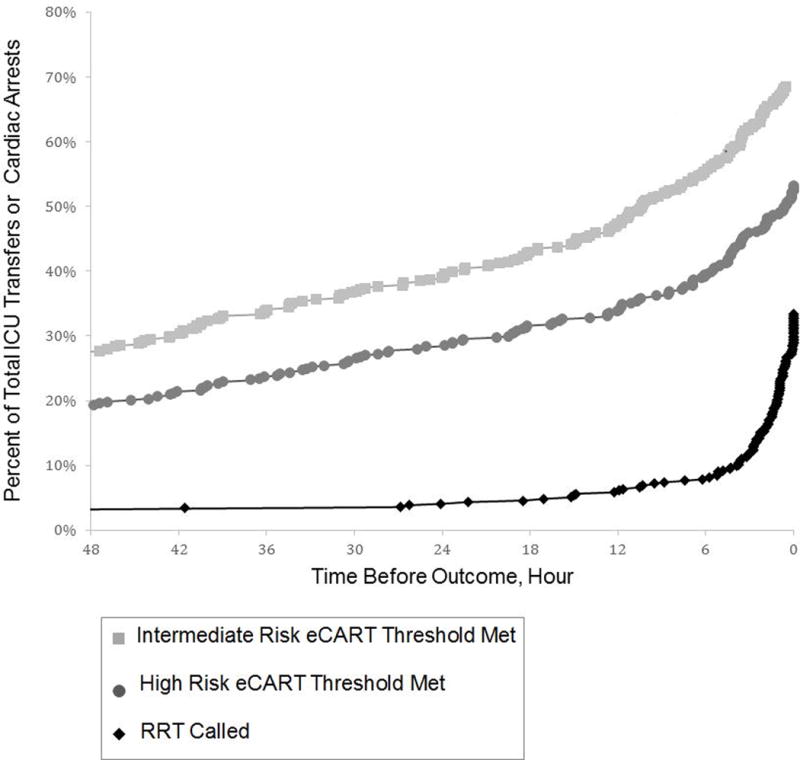

Cardiac arrest patients first triggered a high-risk score a median of 24.7 hours prior to cardiac arrest and an intermediate-risk score a median of 44.4 hours beforehand. Of the two cardiac arrest cases in which a standard of care RRT call was triggered, one RRT call was triggered 4.8 hours prior to arrest and the other was triggered 5 minutes prior to arrest. ICU transfer patients first triggered a high-risk score a median of 29.6 hours prior to transfer and an intermediate-risk score a median of 33.1 hours beforehand. RRT calls were only triggered a median of 1.7 hours before ICU transfer (Figure 3). In paired analysis, for those patients having a poor outcome who also met an eCART threshold and were seen by the RRT, the high-risk threshold was met a median of 11.1 hours prior to RRT call [n=88], and the intermediate-risk threshold was met 20.5 hours beforehand [n=104]; p<0.001 for both comparisons.

Figure 3.

Timing of RRT and eCART Activation Prior to Adverse Event

DISCUSSION

We demonstrated the feasibility of prospective real-time eCART calculation in a general ward setting and found that it detected four times as many cardiac arrests and 50% more ICU transfers compared to our current RRT activation system. Furthermore, we found that patient eCART scores met the high-risk threshold more than eight hours prior to RRT activation and the intermediate-risk threshold almost a full day prior. This lead time should provide sufficient opportunity for earlier clinical assessment and intervention with the hopes of improving patients outcomes (4–7,16,17).

To our knowledge, our black-box study is the first to directly compare the real-time performance of a statistically derived prediction model to the current hospital RRT activation system on the same patients without altering clinical interventions. This study was not designed to test the impact of eCART risk stratification on clinical outcomes but rather to evaluate its prospective performance independent from the downstream RRT system. Thus, we were able to assess the sensitivity and specificity of real-time eCART scoring for predicting patient adverse outcomes, and describe the lead time in identifying patient deterioration using eCART compared to our current RRT activation system. In contrast, an implementation study affecting clinical workflow could only test the entire RRT system and would not be able to directly compare the performance of the scoring tool to the traditional RRT activation system within the same patient population. Therefore, in implementation studies that have failed to demonstrate an improvement in patient outcomes, it is impossible to determine whether the problem lay with the prediction model or the downstream RRT system.

Several studies have directly implemented and evaluated real-time electronic risk prediction systems with mixed results. Huh and colleagues demonstrated a reduction in ICU transfers using a single parameter activation criteria system (18). And Bellomo et al demonstrated a reduction in mortality in a multicenter heterogeneous intervention (19). However, a study by Kollef et al failed to demonstrate reductions in either ICU transfer or mortality (20).

Our analysis of RRT activation timing not only demonstrated that real-time eCART calculation would have activated the RRT much earlier than current practice, but also revealed that only 15% of ICU transfer patients actually triggered an RRT more than two hours before transfer. While this was not an interventional study and therefore we were unable to measure the impact on outcomes, it is possible that earlier notification of the Rapid Response Team could result in more patients being stabilized on the floor, thereby averting ICU transfer entirely, or earlier recognition that ICU transfer is required, which could decrease transfer delays. Several studies have demonstrated increased mortality for patients experiencing delays in ICU transfer (6,21). In one study, Cardoso et al found that patients in need of an ICU transfer had a 1.5% increased risk of death for every hour that transfer was delayed (4). However, improvements in patient outcomes are not the only targets for such an intervention. Several studies have shown that better monitoring and notification of caregivers for high-risk patients decreases hospital length of stay (20,22). For example, Kollef and colleagues found a one-day decrease in hospital length of stay associated with the implementation of their system.

Our study has several limitations. First, as this was a single center study, the results may not be generalizable to other hospitals and patient populations. However, our AUCs were similar to our retrospective study as well as a subsequent multicenter study of eCART (13,23). Second, because this study compared real-time eCART calculation to the current system, which promoted the activation of RRTs for clinical deterioration, we were unable to identify the subset of patients who would have suffered an adverse outcome but had a successful intervention by an RRT or the clinical team. However, because our plan is for real-time eCART calculation to work with the current RRT calling system, not as a replacement, we only needed to determine whether it was able to accurately identify patients that were missed by the current system. Additionally, we did not have data on interventions taking place in the time between the patient meeting the high-risk eCART threshold and the time of outcome. Therefore, clinical interventions that ultimately prevented a cardiac arrest or eliminated the need for ICU transfer may have taken place, resulting in an overestimation of our false positive rate. Finally, because this was a black-box study, it is unknown whether earlier notification by eCART would have altered the frequency or timing of ICU transfers. Future work will be needed to assess the impact of automated RRT triggering by eCART on patient outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that eCART identified many high-risk patients missed by the current RRT system and, for those for whom the RRT was called, identified them hours in advance of the standard RRT activation. As such, real-time calculation and notification of the RRT using a statistically derived and validated score has the potential to provide earlier intervention for patients becoming critically ill on the wards and improve patient outcomes and resource utilization.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to John Chung, Prasanna Nippani, and Chicago Biomedicine Information Services (CBIS) for development and implementation of the real-time infrastructure. Data from this study were provided by the Clinical Research Data Warehouse (CRDW) maintained by the Center for Research Informatics (CRI) at University of Chicago. The CRI is funded by the Biological Sciences Division, the Institute for Translational Medicine/CTSA (NIH UL1 TR000430) at the University of Chicago.

Source of Funding: Work completed by Michael Kang was supported in part by funding from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (#2T35AG029795-07). Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending (ARCD. P0535US.P2) for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients. Dr. Churpek is supported by a career development award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080). Dr. Edelson has received research support and honoraria from Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA), research support from the American Heart Association (Dallas, TX) and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway). She has ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), which is developing products for risk stratification of hospitalized patients.

Copyright form disclosures: Dr. Edelson received funding from Ownership interest in Quant HC (Chicago, IL), disclosed other support (Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending [ARCD. P0535US.P2] for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients), and received support for article research from the NIH. Her institution received funding from National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (#2T35AG029795- 07); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K08 HL121080); American Heart Association (Dallas, TX) and Laerdal Medical (Stavanger, Norway); and Philips Healthcare (Andover, MA). Dr. Kang received support for article research from the NIH and received funding from National Institute on Aging (Grant #2T35AG029795-07). Dr. Churpek received support for article research from the NIH and disclosed other relationships (Drs. Churpek and Edelson have a patent pending [ARCD. P0535US.P2] for risk stratification algorithms for hospitalized patients). His institution received funding from an NHLBI K08 grant.

Footnotes

Preliminary versions of these data were presented as a poster presentation at the 2015 meeting of the American Thoracic Society (May 19, 2015; Denver, CA).

Author Contributions: Study concept and design: M.C., D.P.E.; acquisition of data: F.Z., R.A., N.T.; analysis and interpretation of data: all authors; first drafting of the manuscript: M.K.; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors; statistical analysis: M.K.; M.C.; obtained funding: all authors; administrative, technical, and material support: M.C., F.Z., R.A., N.T., D.P.E.; study supervision: M.C., D.P.E,. Data access and responsibility: M.K. and M.C had full access to all the data in the study, and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflicts of Interest: All other authors report no conflicts of interest.

The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Edelson DP. Risk Stratification of Hospitalized Patients on the Wards. CHEST J. 2013 Jun 1;143(6):1758. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jones DA, DeVita MA, Bellomo R. Rapid-Response Teams. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):139–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0910926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Churpek MM. Predicting Cardiac Arrest on the Wards: A Nested Case-Control Study. CHEST J. 2012 May 1;141(5):1170. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardoso LT, Grion CM, Matsuo T, Anami EH, Kauss IA, Seko L, et al. Impact of delayed admission to intensive care units on mortality of critically ill patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2011;15(1):R28. doi: 10.1186/cc9975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early Goal-Directed Therapy in the Treatment of Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 8;345(19):1368–77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mardini L, Lipes J, Jayaraman D. Adverse outcomes associated with delayed intensive care consultation in medical and surgical inpatients. J Crit Care. 2012 Dec;27(6):688–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, Light B, Parrillo JE, Sharma S, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock*. Crit Care Med. 2006 Jun;34(6):1589–96. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Edelson DP, Yuen TC, Mancini ME, Davis DP, Hunt EA, Miller JA, et al. Hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation practice in the United States: A nationally representative survey: In-hospital CPR Practices. J Hosp Med. 2014 Jun;9(6):353–7. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan PS, Jain R, Nallmothu BK, Berg RA, Sasson C. Rapid response teams: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010 Jan 11;170(1):18–26. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edelson DP. A weak link in the rapid response system. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(1):12–3. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeVita MA, Smith GB, Adam SK, Adams-Pizarro I, Buist M, Bellomo R, et al. “Identifying the hospitalised patient in crisis”—A consensus conference on the afferent limb of Rapid Response Systems. Resuscitation. 2010;81(4):375–82. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao H, McDonnell A, Harrison DA, Moore T, Adam S, Daly K, et al. Systematic review and evaluation of physiological track and trigger warning systems for identifying at-risk patients on the ward. Intensive Care Med. 2007 Mar 23;33(4):667–79. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0532-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Park SY, Gibbons R, Edelson DP. Using electronic health record data to develop and validate a prediction model for adverse outcomes in the wards*. Crit Care Med. 2014 Apr;42(4):841–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Park SY, Meltzer DO, Hall JB, Edelson DP. Derivation of a cardiac arrest prediction model using ward vital signs*. Crit Care Med. 2012 Jul;40(7):2102–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318250aa5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the Areas under Two or More Correlated Receiver Operating Characteristic Curves: A Nonparametric Approach. Biometrics. 1988 Sep;44(3):837. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J, Bellomo R, Flabouris A, Hillman K, Finfer S. The relationship between early emergency team calls and serious adverse events*. Crit Care Med. 2009 Jan;37(1):148–53. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181928ce3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McQuillan P, Pilkington S, Allan A, Taylor B, Short A, Morgan G, et al. Confidential inquiry into quality of care before admission to intensive care. Bmj. 1998;316(7148):1853–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7148.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huh JW, Lim C-M, Koh Y, Lee J, Jung Y-K, Seo H-S, et al. Activation of a Medical Emergency Team Using an Electronic Medical Recording–Based Screening System*. Crit Care Med. 2014 Apr;42(4):801–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellomo R, Ackerman M, Bailey M, Beale R, Clancy G, Danesh V, et al. A controlled trial of electronic automated advisory vital signs monitoring in general hospital wards*. Crit Care Med. 2012 Aug;40(8):2349–61. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318255d9a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kollef MH, Chen Y, Heard K, LaRossa GN, Lu C, Martin NR, et al. A randomized trial of real-time automated clinical deterioration alerts sent to a rapid response team: Clinical Deterioration Alerts. J Hosp Med. 2014 Apr;:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Young MP, Gooder VJ, Bride K, James B, Fisher ES. Inpatient transfers to the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):77–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown H, Terrence J, Vasquez P, Bates DW, Zimlichman E. Continuous Monitoring in an Inpatient Medical-Surgical Unit: A Controlled Clinical Trial. Am J Med. 2014 Mar;127(3):226–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Churpek MM, Yuen TC, Winslow C, Robicsek AA, Meltzer DO, Gibbons RD, et al. Multicenter Development and Validation of a Risk Stratification Tool for Ward Patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 Sep 15;190(6):649–55. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201406-1022OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]