Abstract

Vaporizing drugs in e-cigarettes is becoming a common method of administration for synthetic cathinones and classical stimulants. Heating during vaporization can expose the user to a cocktail of parent compound and thermolytic degradants, which could lead to different toxicological and pharmacological effects compared to ingesting the parent compound alone via injection or nasal inhalation. This study examined the in vivo toxicological and pharmacological effects of vaporized and injected methamphetamine (METH) and α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP). Male and female ICR mice were administered METH or α-PVP through vapor or i.p. injection. Dose-effect curves were determined for locomotor activity and a functional observational battery (FOB). METH and α-PVP vapor were also evaluated for place preference in male mice. Vapor exposure and injection led to more similarities than differences in toxicological and pharmacological effects. In the FOB, both routes of administration produced typical stimulant effects, and injection also increased some bizarre behaviors (e.g. licking, teeth chattering, darting). Both METH and α-PVP vapor exposure produced conditioned place preference. The two routes of administration had comparable efficacy in locomotor activation, with vapor producing longer lasting effects than injection. Females showed greater METH-induced locomotor activity, and greater incidence of a few somatic signs in the FOB than males. These results explore the toxicology of stimulant vapor inhalation in mice using an e-cigarette device. Despite the current technological and methodological difficulties, studying drug vapor promises to allow determination of toxicological effects of thermolytic products and flavor additives.

Keywords: α-PVP, functional observational battery, locomotor activity, methamphetamine, conditioned place preference, vapor

1.0 Introduction

Products containing synthetic cathinones, commonly sold as “bath salts” or “research chemicals,” arrived on the recreational drug market in recent years (Baumann et al., 2013; Psychonaut, 2009; U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, 2013). These products are purchased online as “legal” alternatives to “ecstasy,” methamphetamine (METH), or other illicit drugs of abuse (EMCDDA, 2015; Karila and Reynaud, 2011; Schifano et al., 2011; Winstock and Ramsey, 2010; Winstock et al., 2011). As earlier synthetic cathinones were banned, manufacturers introduced a new supply of novel compounds to serve as replacements (Brandt et al., 2010; Fratantonio et al., 2015; Shanks et al., 2012). One of these replacements, alpha-pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP) (also known as “gravel” or “flakka”), was detected in the U.S. with accelerating frequency from 2013 to 2014 (U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, 2014, 2015). Despite an emergency ban in 2014 (United States Department of Justice, 2014), use of α-PVP continued to increase substantially throughout 2015, during which it was implicated in at least 16 deaths in the U.S. (National Drug Early Warning System, 2015b). In Florida, α-PVP seizures tripled in the first half of 2015 in comparison to all of 2014 (Fratantonio et al., 2015), and reports of α-PVP-induced excited delirium were widespread (National Drug Early Warning System, 2015b). Large scale seizures of α-PVP also occurred throughout Europe in 2015 (EMDCCA, 2015).

Smoking/vaporizing synthetic cathinones was first documented in a survey conducted in 2012–2013 (Johnson & Johnson, 2014), a time period concomitant with the popularization of e-cigarette devices. Similar to cocaine and METH (Anglin et al., 2000; Beebe & Walley, 1995; Jeffcoat et al., 1989), smoking/vaporizing synthetic cathinones produces a very rapid onset of effects (7.5 s) and a shorter duration of action compared to nasal inhalation (i.e. snorting) (Johnson & Johnson, 2014). The quick onset and short duration of action suggests that smoking/vaporizing is likely to be the preferred route of administration (Fischman, 1989; Hatsukami & Fischman 1996), providing that the compounds are easily volatilized and smoking/vaporizing equipment is readily available. In fact, e-cigarettes are increasingly being used to vaporize a variety of drugs, including METH and α-PVP (EMCDDA 2015; National Drug Early Warning System, 2015a, 2015b; Rass et al., 2015), and users report achieving the desired effects when vaporizing METH or synthetic cathinones (Rass et al., 2015).

Nasal inhalation and injection, which are common routes of administration for stimulants, expose users to the parent compound and potential additives, whereas heating and inhaling stimulants may cause thermolysis, exposing the user to a chemical cocktail including the parent compound, additives, and numerous degradants. These degradants may have psychoactive properties of their own, and may be more potent or more toxic than the parent compound. Thermolytic degradants of METH and cocaine include potential carcinogens, and other toxins that cause bronchoconstriction, hypotension, and tachycardia (Chen et al., 1994; Sato et al., 2004; Scheidweiler et al., 2003). The synthetic cathinone mephedrone creates degradants that cause lachrymation and respiratory irritation (Kavanagh et al., 2013). Furthermore, METH and cocaine thermolysis create psychoactive degradants including cocaethylene, amphetamine, and ephedrine (Gayton-ely et al., 2007; Sekine and Nakahara, 1987).

The purpose of this study was to determine the in vivo toxicological and pharmacological effects of vaporized stimulants using an e-cigarette-like device. Since classical stimulants and synthetic cathinones are currently being abused through vaporization, one classical stimulant (METH) and one synthetic cathinone (α-PVP) were examined. Additionally, analysis of these two compounds provides information on the thermolytic degradants of transporter releasers (METH) and transporter uptake inhibitors (α-PVP) (Rickli et al., 2015).

2.0 Methods

2.1 Subjects

Adult male and female ICR mice (Harlan/Envigo, Frederick, MD, USA) (total n=136) were housed individually in polycarbonate cages with hardwood bedding. Male mice weighed 31–51 g and female mice weighed 27–42 g. Mice were housed in temperature-controlled conditions (20–24°C) with a 12 h standard light-dark cycle (lights on at 0600), and had ad libitum access to food and water in their home cages at all times. Experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Mispro Biotech. All research was conducted as humanely as possible, and followed the principles of laboratory animal care (National Research Council, 2011).

2.2 Drugs

Methamphetamine was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). α-Pyrrolidinopentiophenone (α-PVP) was synthesized in house using standard synthetic procedures. It was formulated as recrystalized salt and was > 97% pure. The purity was assessed by several analytical techniques including carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen (CHN) combustion analysis and proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Compounds were dissolved in sterile saline USP (Butler Schein, Dublin, OH) for injection, and in 50% propylene glycol + 50% vegetable glycerin (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburg, PA; J.T. Baker, Center Valley, PA) for vaporization, a vehicle that is commonly used in e-cigarettes. Injected doses are expressed as mg/kg of the salt, and were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) at a volume of 10 ml/kg. Vapor exposure concentrations are expressed as mg/ml of the salt in the e-cigarette tank, and are not representative of the actual amount of drug inhaled. Sterile saline vehicle and 50% propylene glycol + 50% glycerin vehicle were used as comparisons for injected and vaporized compounds, respectively.

2.3 Apparatus for Vapor Delivery

Vapor was generated using a custom built system that included a modified electronic cigarette (iStick 30W Variable Wattage; eLeaf, Irvine, CA) which heated and vaporized compounds. An atomizer generated vapor, and then an air pump pushed the vapor through the reservoir tank containing the drug solution at a flow rate of 1 L/min. The tank was connected to a small Plexiglas exposure chamber (E-Z-Anesthesia™ EZ177; 10 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm; 1000mL volume) where the mouse was located. The system was configured at 7W using a 1.8Ω atomizer. During exposure periods, approximately 0.01 mL of liquid was vaporized, and the chamber was filled with drug vapor over the course of 10 s. The mouse then remained in the exposure chamber for 5 min (Hueza et al., 2016; Meng et al., 1997, 1999), with no additional vapor introduced.

2.4 Apparatus for Functional Observation Battery (FOB) and Locomotor Activity

FOBs and locomotor activity sessions were conducted in clear Plexiglas open fields measuring 47 × 25.5 × 22 cm. San Diego Instruments Photobeam Activity System software (model 2325-0223, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to calculate beam breaks during locomotor sessions. Each chamber contained two 4 × 8 beam infrared arrays that monitored horizontal movement.

2.5 Apparatus for CPP

Conditioned place preference (CPP) sessions were conducted in an automated system with three-compartment chambers. Side compartments were 27.5 cm × 22 cm × 31.5 cm and the center compartment was 14 cm × 22 cm × 31.5 cm. Each chamber contained an array of 4 × 16 photocell infrared beams. San Diego Systems software (model 6610-001-A, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to calculate beam breams and time spent in each chamber. Each side compartment was marked with distinct patterns, and the equipment was unbiased.

2.6 FOB and Locomotor Activity

Mice were randomly assigned to a drug or vehicle group (n=8 per sex per group). Vaporized drug or vehicle was administered before the first round of testing, and injected drug or vehicle was administered before the second round of testing, with a minimum 7-day wash out between administrations. Concentrations/doses, routes of administration, and progression through the study in time are presented in Table 1. Injected doses were chosen based on previous research (Marusich et al., 2012, 2014). Liquid concentrations for vapor delivery were determined by applying ICR mouse respiration data (Fairchild, 1972) and vapor delivery system settings to the chosen injection doses. Liquid concentrations for vapor delivery were 24.0–134.4 mg/ml METH, 24.0–240.0 mg/ml α-PVP, and propylene glycol/vegetable glycerin (PG/VG) vehicle. Injected doses were 1.0–5.6 mg/kg METH, 1.0–10.0 mg/kg α-PVP, and saline vehicle. Mice were administered the same drug for vapor and injection exposures.

Table 1.

Concentrations/doses administered to each group of mice (n = 8) during the FOB and locomotor activity phases of the experiment.

| FOB and 60 min Locomotor | 6 hr Locomotor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 1 - Vapor | Week 2 - Injection | Week 3 - Vapor | Week 4 - Injection | |

| Group 1 | PG/VG | Saline | PG/VG | Saline |

| Group 2 | 24.0 mg/ml METH | 1.0 mg/kg METH | ||

| Group 3 | 72.0 mg/ml METH | 3.0 mg/kg METH | 24.0 mg/ml METH | 1.0 mg/kg METH |

| Group 4 | 134.4 mg/ml METH | 5.6 mg/kg METH | ||

| Group 5 | 24.0 mg/ml α-PVP | 1.0 mg/kg α-PVP | ||

| Group 6 | 72.0 mg/ml α-PVP | 3.0 mg/kg α-PVP | 72.0 mg/ml α-PVP | 3.0 mg/kg α-PVP |

| Group 7 | 240.0 mg/ml α-PVP | 10.0 mg/kg α-PVP | ||

2.6.1 FOB

An FOB was used to measure observable effects of the drugs, focusing on detection of possible safety concerns (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 1998a, 1998b). The FOB began 5 min after the end of vapor exposure or 10 min post-injection, equating time from initial drug exposure (beginning of 5 min vapor exposure period or injection) to FOB. Mice were observed for 5 min, and FOBs were scored by a trained technician. While the technician was not blind to treatment, this was the first study in this lab on vaporized drug effects, and the FOB was conducted before the technician observed animals in other assays. Both of which minimized experimenter bias. Somatic signs were scored on an ordinal scale, with 1 = normal/no drug effect, 2 = minor-moderate drug effect, and 3 = major drug effect. Methods were similar to those used in our previous studies (Marusich et al., 2012, 2014, 2016). Dependent measures included ataxia, bizarre behavior (e.g. licking the cage wall, teeth chattering, darting in different directions), circular ambulations, convulsions, flattened body posture, grooming, hyperactivity, hypoactivity, piloerection, rapid head movements, retropulsion, salivation, self-injury, stimulation (e.g. increased respiration rate), Straub tail, and tremor.

2.6.2 Locomotor Activity – 60 min Sessions

Locomotor assessments began immediately after the FOB, and were quantified by an automated system that provided a general measure of movement in the horizontal plane across time. Locomotor activity was measured for 60 min, with data collected in 10 min bins.

2.6.3 Locomotor Activity – 6 hr Sessions

A subset of male and female mice from the FOB (n=32 per sex) was reused to determine the time course of locomotor effects in a 6 hr session (see Table 1). Mice were given 2 additional exposures of the same drug or vehicle to which they were exposed previously, with a minimum 7-day wash out between each administration. The first administration was vaporized drug or vehicle, and the second was injected drug or vehicle. Liquid concentrations for vapor delivery and injected doses that produced approximately equivalent locomotor activation for initial groups (see Figure 1) were assessed (vapor: 24.0 mg/ml METH, 72 mg/ml α-PVP, PG/VG; injection: 1.0 mg/kg METH, 3.0 mg/kg α-PVP, saline). Sessions began immediately after drug exposure, and data were collected in 10 min bins.

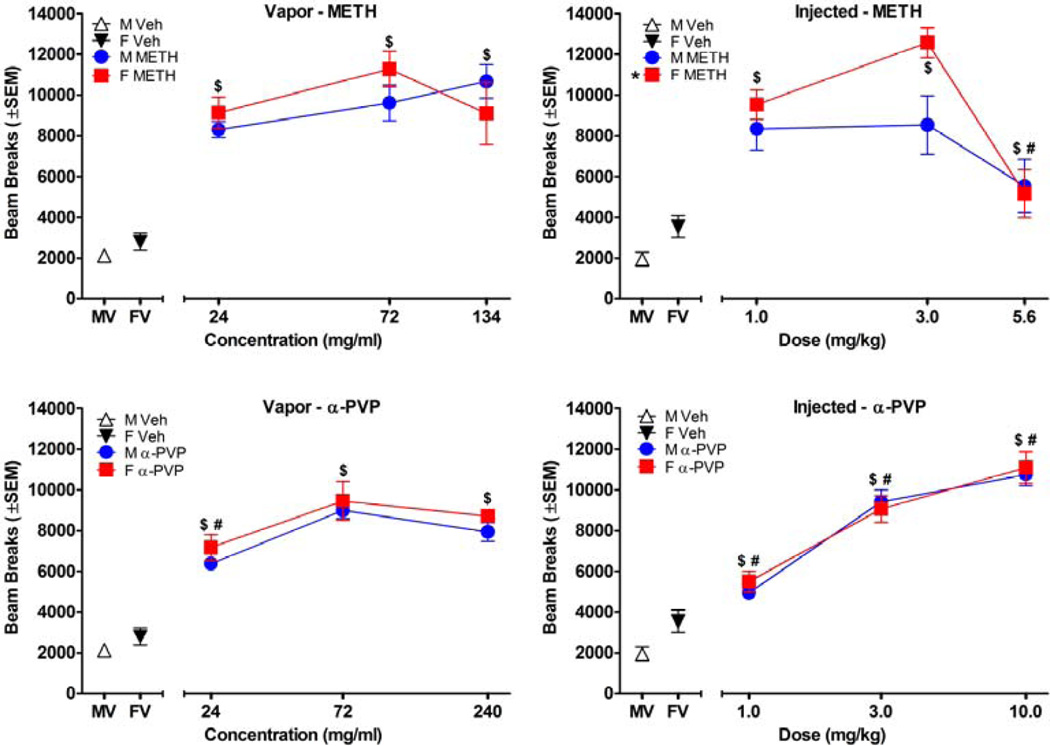

Figure 1.

Effects of test drugs on cumulative locomotor activity during 60 min sessions, plotted as a function of concentration (n=8/group). Top panels shows data for METH, bottom panels show data for α-PVP, left panels show data for vapor, and right panels shows data for injection. * in panel legends indicate a significant difference from male (main effect) for the same drug and route of exposure. $ indicates significant increases in beam breaks compared to vehicle (main effect). # indicates active concentrations that were significantly different from all other active concentrations for the same route of administration (main effect). M stands for male, F stands for female, MV stands for male vehicle, and FV stands for female vehicle.

2.7 Vapor Exposure CPP

The CPP procedure was used to assess rewarding drug effects (Carr et al., 1989; Tzschentke, 1998). Since CPP has been demonstrated with injected METH and α-PVP (Cherng et al., 2007; Gatch et al., 2015; Schindler et al., 2002; Shimosato and Ohkuma, 2000; Zakharova et al., 2009), vapor exposure was the only route of administration used in this assay. A new cohort of male mice were randomly assigned to 24.0 mg/ml METH vapor, 72 mg/ml α-PVP vapor, or PG/VG vehicle groups (n=8 per group). On Day 1, mice had access to all compartments of the apparatus during a 15 min pre-conditioning session. Conditioning day side assignment was biased with drug paired with the originally non-preferred side of the chamber. Conditioning sessions, in which mice were confined to one side compartment, occurred twice daily for 3 days, and began immediately following 5 min of vapor exposure. Mice were exposed to PG/VG vehicle before morning sessions, and exposed to drug before afternoon sessions, except that the PG/VG group was exposed to PG/VG prior to both sessions. Conditioning sessions lasted 30 min and were separated by approximately 4.5 hrs. On Day 5, mice had access to all compartments of the apparatus during a 15 min post-conditioning session.

2.8 Data Analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using NCSS (2004; Number Cruncher Statistical Systems, Kaysville, Utah, USA). PG/VG vehicle and saline vehicle data were included in graphs and analyses for vaporized and injected drugs, respectively. FOB data were analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance (ANOVA) by ranks for each dependent measure, corrected for ties. Routes of administration and sexes were analyzed separately. Neither drug produced convulsions or self-injury; therefore, these measures were not analyzed. Measures were grouped into four domains: CNS activity (α=0.0167; grooming, hyperactivity, hypoactivity), CNS excitability (α=0.0083; bizarre behavior, circular ambulations, retropulsion, rapid head movements, stimulation, Straub tail, tremor), autonomic effects (α=0.025; piloerection, salivation), and muscle tone/equilibrium (α=0.025; ataxia, flattened body posture) (Bowen et al., 1996; Marusich et al., 2016). Dunn’s post hoc test with Bonferroni correction was used to determine differences between groups.

Locomotor activity was expressed as total beam breaks per 60 min session, and beam breaks per 30-min bin for 6 hr sessions. Between-subject ANOVAs (concentration × sex) were used to analyze dose-effect curves for 60 min sessions. Exposure routes were analyzed separately. Mixed model ANOVAs (bin × concentration × sex) were used to analyze time course data for 6 hr sessions. An additional mixed model ANOVA was used to compare vehicle data from 6 hr sessions for the two exposure routes (bin × route × sex). All tests were considered significant at p<0.05, and were followed with Tukey’s post hoc tests as appropriate.

For CPP, time spent in each compartment during the pre and post-conditioning tests, and number of photocell beam breaks during conditioning sessions were collected. Time spent in the initially non-preferred compartment (“drug side”) on the post-conditioning day was used as the primary measure of CPP (Dewey et al., 1999; Le Foll and Goldberg, 2005). These data were analyzed with a two-sample T-test comparing time spent for each drug group to the vehicle group. Locomotor activity during conditioning sessions was analyzed with mixed model ANOVAs [group (drug or vehicle) × drug exposures (1–3)]. Tukey-Kramer post hoc tests were used to compare means when appropriate. All tests were considered significant at p<0.05.

3.0 Results

3.1 Functional Observational Battery

Somatic signs that were significantly altered in the FOB are displayed in Table 2. Within the CNS activity domain, both exposure routes increased hyperactivity compared to vehicle for METH [vapor male: H(3)=18.02, p<0.0167; vapor female: H(3)=11.56, p<0.0167; inject male: H(3)=19.39, p<0.0167; inject female: H(3)=13.61, p<0.0167] and α-PVP [vapor male: H(3)=24.42, p<0.0167; vapor female: H(3)=25.42, p<0.0167; inject male: H(3)=21.80, p<0.0167; inject female: H(3)=20.23, p<0.0167]. Visual inspection of the data revealed that males showed enhanced hyperactivity for a greater number of drug concentrations than females, particularly for METH.

Table 2.

Somatic signs that were significantly affected by methamphetamine (METH) and α-PVP in the FOB.

| Dependent variable |

METH | α-PVP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vapor (mg/ml) | Injected (mg/kg) | Vapor (mg/ml) | Injected (mg/kg) | |||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| CNS Activity (α=0.0167) | ||||||||

| Hyperactivity | 24.0 (188)* | 24.0 (138) | 1.0 (175)* | 1.0 (156) | 24.0 (275)* | 24.0 (275)* | 1.0 (213)* | 1.0 (156) |

| 72.0 (200)* | 72.0 (188)* | 3.0 (213)* | 3.0 (200)* | 72.0 (250)* | 72.0 (275)* | 3.0 (250)* | 3.0 (222)* | |

| 134.4 (200)* | 134.4 (163) | 5.6 (200)* | 5.6 (175)* | 240.0 (200) | 240.0 (200) | 10.0 (238)* | 10.0 (233)* | |

| CNS Excitability | ||||||||

| Bizarre Behaviors |

24.0 (113) | 24.0 (100) | 1.0 (100) | 1.0 (113) | 24.0 (125) | 24.0 (100) | 1.0 (125) | 1.0 (125) |

| 72.0 (100) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (163)* | 3.0 (125) | 72.0 (125) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (113) | 3.0 (113) | |

| 134.4 (100) | 134.4 (100) | 5.6 (125) | 5.6 (138) | 240.0 (200)* | 240.0 (138) | 10.0 (200)* | 10.0 (200)* | |

| Circular Ambulations |

24.0 (113) | 24.0 (113) | 1.0 (175) | 1.0 (175) | 24.0 (150) | 24.0 (175) | 1.0 (100) | 1.0 (100) |

| 72.0 (100) | 72.0 (163) | 3.0 (163) | 3.0 (225)* | 72.0 (225)* | 72.0 (225)* | 3.0 (213)* | 3.0 (150) | |

| 134.4 (175)* | 134.4 (138) | 5.6 (163) | 5.6 (150) | 240.0 (113) | 240.0 (125) | 10.0 (188)* | 10.0 (188)* | |

| Rapid Head Movements |

24.0 (100) | 24.0 (100) | 1.0 (125) | 1.0 (100) | 24.0 (113) | 24.0 (113) | 1.0 (113) | 1.0 (113) |

| 72.0 (100) | 72.0 (113) | 3.0 (150) | 3.0 (125) | 72.0 (100) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (138) | 3.0 (100) | |

| 134.4 (113) | 134.4 (113) | 5.6 (138) | 5.6 (138) | 240.0 (200)* | 240.0 (150) | 10.0 (163) | 10.0 (150) | |

| Stimulation | 24.0 (100) | 24.0 (100) | 1.0 (113) | 1.0 (113) | 24.0 (150) | 24.0 (125) | 1.0 (150) | 1.0 (125) |

| 72.0 (100) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (113) | 3.0 (100) | 72.0 (113) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (163) | 3.0 (125) | |

| 134.4 (113) | 134.4 (100) | 5.6 (138) | 5.6 (188)* | 240.0 (150) | 240.0 (138) | 10.0 (175) | 10.0 (188)* | |

| Straub Tail | 24.0 (100) | 24.0 (100) | 1.0 (150) | 1.0 (122) | 24.0 (150) | 24.0 (113) | 1.0 (200)* | 1.0 (167)* |

| 72.0 (100) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (200)* | 3.0 (178)* | 72.0 (163) | 72.0 (163) | 3.0 (200)* | 3.0 (178)* | |

| 134.4 (138) | 134.4 (138) | 5.6 (200)* | 5.6 (189)* | 240.0 (175) | 240.0 (188)* | 10.0 (200)* | 10.0 (178)* | |

| Autonomic Effects | ||||||||

| Piloerection | 24.0 (82) | 24.0 (100) | 1.0 (113) | 1.0 (125) | 24.0 (91) | 24.0 (100) | 1.0 (175) | 1.0 (138) |

| 72.0 (73) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (175) | 3.0 (200)* | 72.0 (82) | 72.0 (100) | 3.0 (225)* | 3.0 (175)* | |

| 134.4 (82) | 134.4 (163)* | 5.6 (225)* | 5.6 (288)* | 240.0 (73) | 240.0 (100) | 10.0 (238)* | 10.0 (175) | |

| Muscle tone/Equilibrium (α=0.025) | ||||||||

| Flattened Body Posture |

24.0 (100) | 24.0 (113) | 1.0 (113) | 1.0 (175)* | 24.0 (138) | 24.0 (163) | 1.0 (113) | 1.0 (200)* |

| 72.0 (138) | 72.0 (138) | 3.0 (138) | 3.0 (200)* | 72.0 (100) | 72.0 (138) | 3.0 (138) | 3.0 (138) | |

| 134.4 (163)* | 134.4 (163) | 5.6 (163) | 5.6 (175)* | 240.0 (100) | 240.0 (150) | 10.0 (163) | 10.0 (188)* | |

Concentrations/doses that produced a significant difference from vehicle are followed by asterisks, and the average percent of vehicle is shown in parenthesis.

Corrected alpha levels for each domain are noted in parenthesis in the first row for the domain.

For CNS excitability, injected METH and both routes of α-PVP elevated bizarre behavior for males [METH: H(3)=11.87, p<0.0083; α-PVP vapor: H(3)=18.60, p<0.0083; α-PVP inject: H(3)=13.19, p<0.0083], but not females. Both routes of α-PVP administration increased circular ambulations for both sexes [vapor male: H(3)=20.25, p<0.0083; vapor female: H(3)=14.97, p<0.0083; inject male: H(3)=23.33, p<0.0083; inject female: H(3)=15.32, p<0.0083]. In contrast, METH showed sex by route specific effects for circular ambulations, with vapor-induced effects for males [H(3)=13.63, p<0.0083] and injection-induced effects for females [H(3)=17.95, p<0.0083]. Elevated rapid head movements were specific to α-PVP-vapor-administered males [H(3)=15.83, p<0.0083], and heightened stimulation was specific to injected females [METH: H(3)=15.83, p<0.0083; α-PVP: H(3)=21.96, p<0.0083]. Finally, drug injection led to Straub tail for both sexes and both drugs [METH male: H(3)=22.73, p<0.0083; METH female: H(3)=19.49, p<0.0083; α-PVP male: H(3)=31.00, p<0.0083; α-PVP female: H(3)=21.96, p<0.0083], whereas vaporized α-PVP produced Straub tail only for females [H(3)=16.44, p<0.0083].

For autonomic effects, METH caused piloerection for both sexes, but was limited to injection exposure for males [vapor female: H(3)=17.22, p<0.025; inject male: H(3)=18.62, p<0.025; inject female: H(3)=27.00, p<0.025]. Furthermore, injected, but not vaporized, α-PVP produced piloerection [male: H(3)=21.51, p<0.025; female: H(3)=10.16, p<0.025]. Within the muscle tone/equilibrium domain, METH vapor increased flattened body posture for males [H(3)=11.63, p<0.025], whereas injection of both drugs increased flattened body posture for females [METH: H(3)=15.96, p<0.025; α-PVP: H(3)=14.38, p<0.025].

3.2 Locomotor Dose-Response During 60 Min Sessions

As depicted in Figure 1, both routes of administration and both drugs increased beam breaks [METH vapor: F(3, 56)=39.32, p<0.001; METH inject: F(3, 56)=25.63, p<0.001; α-PVP vapor: F(3, 56)=72.64, p<0.001; α-PVP inject: F(3, 56)=91.07, p<0.001]. Because different doses/concentrations were used, the two routes were not compared statistically; however, visual inspection of the results showed that injection led to greater dose-dependent effects than vapor, as indicated by greater variability in effects across doses. Injected METH was the only drug and route combination that produced a sex difference [F(1, 56)=5.39, p<0.05], with females showing greater activity than males (Figure 1, top right panel).

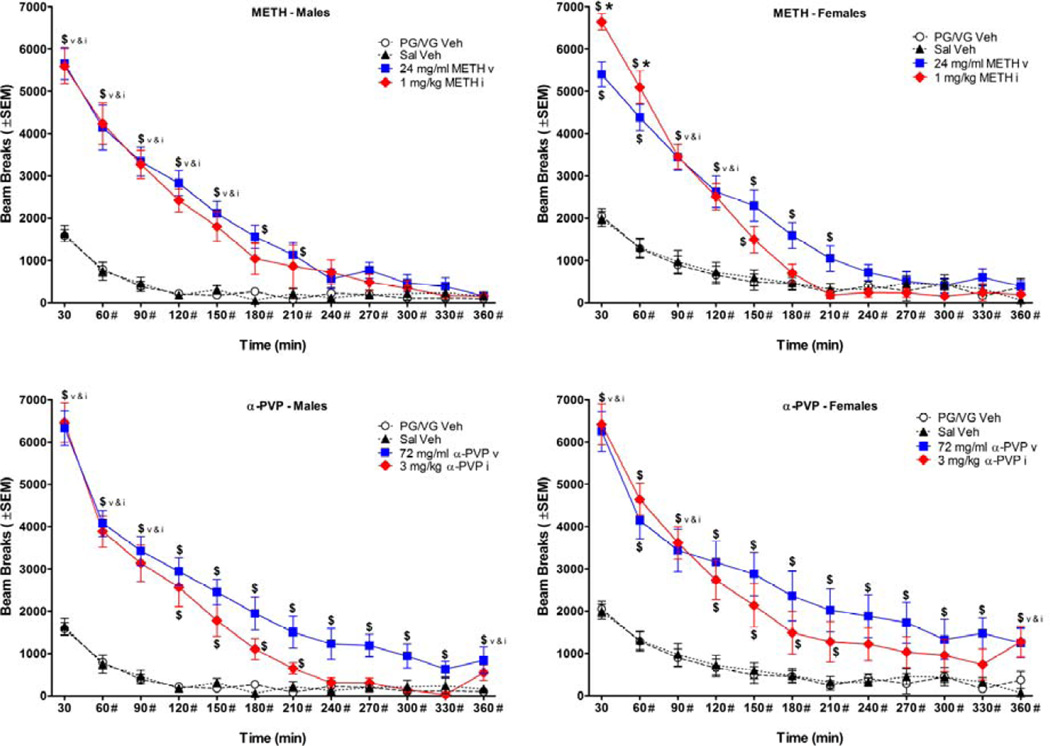

3.3 Locomotor Time course During 6 Hr Sessions

The 6 hr time course for locomotor activity is shown in Figure 2. Vaporized and injected METH and α-PVP increased locomotor activity compared to vehicle for both sexes [METH vapor: F(1, 28)=81.49, p<0.001; METH inject: F(1, 28)=63.46, p<0.001; α-PVP vapor: F(1, 28)=59.45, p<0.001; α-PVP inject: F(1, 28)=44.48, p<0.001]. The duration of locomotor activation compared to vehicle was different for each route of administration, but consistent across drugs with vapor producing longer lasting increases than injection. Vaporized METH and α-PVP elevated beam breaks for 210 and 360 min, respectively, whereas injected METH and α-PVP elevated beam breaks for 150 and 210 min, respectively [METH vapor bin: F(11, 308)=163.64, p<0.001; METH vapor interaction: F(11, 308)=58.36, p<0.001; METH inject bin: F(11, 308)=208.59, p<0.001; METH inject interaction: F(11, 308)=83.38, p<0.001; α-PVP vapor bin: F(11, 308)=130.87, p<0.001; α-PVP vapor interaction: F(11, 308)=39.59, p<0.001; α-PVP inject bin: F(11, 308)=174.34, p<0.001; α-PVP inject interaction: F(11, 308)=64.45, p<0.001].

Figure 2.

Time course of locomotor activity during 6 hr sessions, plotted as a function of 30 min bins (n=8/group). $ indicates a significant difference from vehicle (concentration × bin interaction), and * indicates a significant difference from male (sex × bin interaction) for the same administration route and bin. # beside minutes on the X-axis indicate significant attenuation of effects of PG/VG and saline vehicles compared to the first 30 min bin (main effect). Top panels show data for METH, bottom panels show data for α-PVP, left panels show data for males, and right panels show data for females. PG/VG Veh stands for propylene glycol/vegetable glycerin vehicle, Sal Veh stands for saline vehicle, v stands for vapor, and i stands for injection.

Injected METH was the only route and drug combination that produced a sex difference (Figure 2, top panels). Females displayed greater locomotor activation than males during the first 60 min [sex × bin interaction: F(11, 308)=3.38, p<0.001], an effect that replicated results from the 1 hr locomotor sessions. A comparison of locomotor activity for injection and vapor vehicles showed an effect of bin [F(11, 154)=65.84, p<0.001], with beam breaks attenuating after the first 30 min, but did not show any route of administration differences (Figure 2).

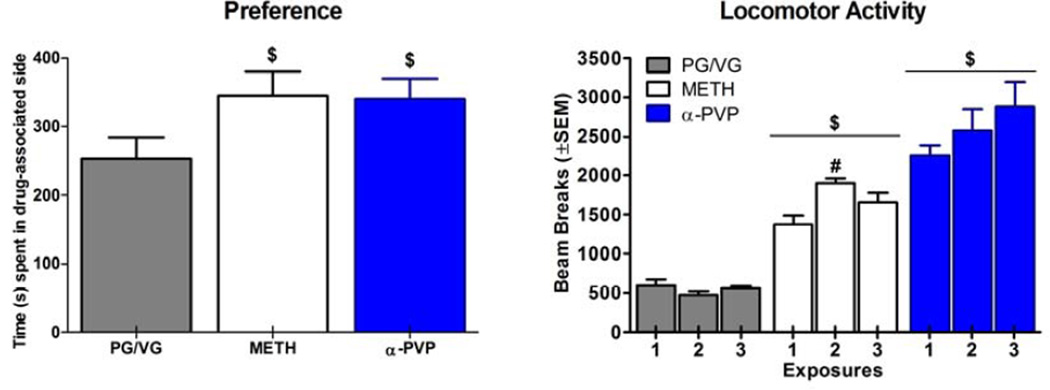

3.4 CPP

Time (s) spent in the drug-associated compartment on the post-conditioning day, and locomotor activity across vapor exposures are shown in Figure 3. Both drugs produced significant CPP compared to the PG/VG group [METH: T(14)=1.94, p<0.05; α-PVP: T(14)=1.99, p<0.05] (Figure 3, left panel). During conditioning days, both drugs elevated beam breaks compared to the PG/VG group [METH: F(1, 14)=94.77, p<0.001; α-PVP: F(1, 14)=58.15, p<0.001]. While there was a significant dose by exposure interaction for both drugs [METH: F(2, 28)=21.96, p<0.001; α-PVP: F(2, 28)=4.27, p<0.05], and α-PVP showed a trend toward locomotor sensitization, activity was not significantly different between any of the 3 exposures for α-PVP. METH produced elevated activity for exposure 2 compared to exposure 1, but did not maintain this elevation for exposure 3 (Figure 3, right panel).

Figure 3.

For each drug, time (s) spent in the drug-associated compartment on the post-conditioning day is shown in the left panel (n=8/group). Locomotor activity following the three drug exposure sessions is shown in the right panel. $ indicates a significant difference from vehicle (main effect), and # indicates a significant difference from the first exposure for the same dose group (exposure × dose interaction). PG/VG stands for propylene glycol/vegetable glycerin vehicle.

4.0 Discussion

In summary, injection of METH and α-PVP produced typical stimulant effects in mice of both sexes, including enhanced locomotor activity and increases in behaviors associated with CNS activation and excitability. These behavioral effects have been previously reported with other classic stimulants and synthetic cathinones in male mice (Aarde et al., 2015; Gatch et al., 2015; Marusich et al., 2012, 2014). Vaporized METH and α-PVP produced a similar profile of stimulant-like overt effects. Although both compounds stimulated locomotor activity with comparable efficacy across the two routes of administration, activity levels at each vapor concentration were similar whereas activity levels exhibited greater dose-dependence with injections, which was especially notable for α-PVP. In agreement with past research using injected METH and α-PVP (Cherng et al., 2007; Gatch et al., 2015; Schindler et al., 2002; Shimosato and Ohkuma, 2000; Zakharova et al., 2009), vapor exposure to both compounds also produced CPP.

While results of the present study did not show large sex differences, a number of subtle differences were observed. FOB results hint at greater route of administration differences for females than males, with a few behaviors more elevated for females following injection compared to vapor (stimulation, flattened body posture). This effect was consistent across drugs, suggesting that classical stimulants and synthetic cathinones may produce similar sex differences in somatic signs. Consistent with past research, injection of METH produced greater locomotor activity for females than males (Milesi-Hallé et al., 2005), an effect that may be related to sex differences in the pharmacokinetics of METH. For example, female rodents show greater levels of METH, and its metabolite amphetamine, in plasma and brain than male rodents (Rambousek et al., 2014). Females also show lower volume of distribution, and lower total clearance of injected METH than males (Milesi-Hallé et al., 2005). In contrast, sex differences in METH-induced hyperactivity were not noted following vapor exposure. As relatively few studies have examined sex differences in stimulant effects and even fewer have administered stimulant via vapor exposure, the degree to which the lack of sex difference observed here is related to greater cross-sex similarity in the pharmacokinetics of METH after vapor exposure or to some other factor is unknown and awaits further research.

Another unexpected difference with vapor exposure was that it induced longer lasting locomotor stimulation than injection, an effect that was more pronounced for α-PVP than for METH. This finding would appear to be contrary to self-reported shorter durations of subjective effects following smoking/vaporizing in humans (Anglin et al., 2000; Beebe & Walley, 1995; Johnson & Johnson, 2014); however, the cross-species disparity could be related to differences in the effect measured (i.e., locomotor activity vs. subjective effects) or to differences in respiratory physiology between mice and humans. Although beyond the scope of the present initial study, evaluation of the time course of a range of doses/concentrations would have allowed better assessment of the equivalence of injected doses versus inhaled concentrations.

Characteristic stimulant effects were produced with each route of administration, suggesting high abuse potential for human drug users regardless of route. Since humans prefer stimulants with a shorter duration of action (Fischman, 1989; Hatsukami & Fischman 1996), injection might be more appealing than vapor due to the shorter time course for injection versus vapor. On the other hand, drug vapor produced greater similarity in effects across concentrations than injection. To the extent that these findings may be applied to human vaping, these results suggests that vapor may lead to a more reliable and predictable experience than injection, an effect that is likely important for established users. In the FOB, fewer adverse effects were observed for vapor than injection, suggesting that vapor would be the preferred route for people primarily seeking prototypic stimulant effects.

Data from human drug abusers support the conclusion that both injection and smoking/vaporizing can contribute to abuse liability of stimulants, but in different ways. Among METH users seeking treatment, METH smokers reported more compulsive use, quicker onset of psychosis, and faster treatment seeking than METH injectors (i.v.) (Matsumoto et al., 2002; McKetin et al., 2008). In contrast, METH injectors were more likely to be dependent on METH, and more likely to experience auditory hallucinations compared to METH smokers (Matsumoto et al., 2002; McKetin et al., 2008).

Limitations of the present study are that the amount of drug inhaled from vapor was not determined, and drug concentrations used to generate vapor were not adjusted for body weight. While our system specifications provide an estimate of milligrams vaporized, ascertaining doses of inhaled drug during vapor exposure is challenging, partly due to the lack of information on ICR mouse respiration parameters. Only male ICR mice have been examined, and the average weight of those mice was 11 g less than the average male mouse in the present study (Fairchild, 1972), making estimation of our subjects’ respiration parameters difficult. Another method to determine the amount of drug inhaled is to measure drug levels in blood and brain after in vivo assessments. A previous study found that i.v. injection and vapor inhalation produced similar brain levels of METH, but vapor exposure led to greater concentrations of METH in plasma and whole body compared to i.v. injection (Meng et al., 1999). The lack of definitive a priori vapor inhalation doses may have led to examination of a smaller dose range for vapor than anticipated, which may explain the similarities in locomotor effects across vapor concentrations. Similarly, not adjusting concentration based on body weight may have contributed to sex differences in effects; however, it is unclear if adjusting for body weight is the best method for ensuring a consistent vapor inhalation dose across animals. It is possible that adjusting for respiration rate and volume would provide more consistent doses than adjusting for weight. As the study of drug vapor abuse expands, it will be important to determine various species parameters that influence drug vapor inhalation such as age, sex, strain, and weight to allow greater flexibility in experimental methods.

A second limitation is that vapor created under the conditions used in the present study was not analyzed for thermolytic products. While previous analytical studies identified thermolytic degradants of METH that produce harmful effects and psychoactive effects (Gayton-ely et al., 2007; Sato et al., 2004; Sekine and Nakahara, 1987), the degree to which these degradants (or others) were generated under the heating conditions used in the present study remains unknown. Results show subtle route of administration differences such as alterations in time course, and potential route by sex interactions in the FOB. This suggests that vaporizing METH and α-PVP may have produced chemical alterations in the parent compounds, but it is yet to be determined if the different results across routes of administration are the product of the thermolytic process, differences in pharmacokinetics, or both.

5.0 Conclusion

In conclusion, the present results demonstrate that exposure to METH and α-PVP vapor produce stimulant-like effects that are similar to those observed following i.p. injection, including rewarding effects (in male mice). Furthermore, female mice showed greater increases in locomotor activity and greater incidence of a few somatic signs in the FOB after METH injection than males, sex differences that were not noted following vapor exposure. Although several limitations were associated with vapor exposure (e.g., difficulty of exact dose calculation), this study provides information on the toxicology of inhaled stimulants of abuse in mice. Despite the current technological and methodological difficulties, studying drug vapor promises to allow determination of toxicological effects of thermolytic products and flavor additives.

Highlights.

Vaporizing stimulants in e-cigarettes is becoming a common method of administration.

The pharmacology of methamphetamine and α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone vapor was studied.

Vapor exposure and injection produced similar pharmacological effects in mice.

E-cigarettes are a feasible method to expose mice to drugs of abuse via inhalation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ricardo Cortes and Tony Landavazo for technical assistance. Research was generously supported by RTI International internal research and development funds, and NIH/NIDA Grants DA12970 and DA040460. The funding source had no other role other than financial support. All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript, and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aarde SM, Creehan KM, Vandewater SA, Dickerson TJ, Taffe MA. In vivo potency and efficacy of the novel cathinone α-pyrrolidinopentiophenone and 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone: self-administration and locomotor stimulation in male rats. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:3045–3055. doi: 10.1007/s00213-015-3944-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anglin MD, Burke C, Perrochet B, Stamper E, Dawud-Noursi S. History of the methamphetamine problem. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2000;32(2):137–141. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2000.10400221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann MH, Partilla JS, Lehner KR. Psychoactive “bath salts”: not so soothing. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2013;698(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beebe DK, Walley E. Smokable methamphetamine ('ice'): an old drug in a different form. American Family Physician. 1995;51(2):449–453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen SE, Wiley JL, Evans EB, Tokarz ME, Balster RL. Functional observational battery comparing effects of ethanol, 1, 1, 1-trichloroethane, ether, and flurothyl. Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 1996;18(5):577–585. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(96)00064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt SD, Sumnall HR, Measham F, Cole J. Analyses of second-generation ‘legal highs’ in the UK: Initial findings. Drug Testing and Analysis. 2010;2(8):377–382. doi: 10.1002/dta.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr GD, Fibiger HC, Phillips AG. Conditioned place preference as a measure of drug reward. In: Liebman JM, Cooper SJ, editors. The neuropharmacological basis of reward. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1989. pp. 264–319. [Google Scholar]

- Chen LC, Graefe JF, Shojaie J, Willetts J, Wood RW. Pulmonary effects of the cocaine pyrolysis product, methylecgonidine, in guinea pigs. Life Sciences. 1994;56(1):PL7–PL12. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00410-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherng CG, Tsai CW, Tsai YP, Ho MC, Kao SF, Yu L. Methamphetamine-disrupted sensory processing mediates conditioned place preference performance. Behavioural Brain Research. 2007;182(1):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Brodie JD, Gerasimov M, Horan B, Gardner EL, Ashby CR. A pharmacologic strategy for the treatment of nicotine addiction. Synapse. 1999;31(1):76–86. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199901)31:1<76::AID-SYN10>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction) Europol Joint Report on a new psychoactive substance: 1-phenyl-2-(1-pyrrolidinyl)-1-pentanone (α-PVP) 2015 Available at http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/attachements.cfm/att_242501_EN_TDAS15001ENN.pdf.

- Fairchild GA. Measurement of respiratory volume for virus retention studies in mice. Applied Microbiology. 1972;24(5):812–818. doi: 10.1128/am.24.5.812-818.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischman MW. Relationship between self-reported drug effects and their reinforcing effects: studies with stimulant drugs. NIDA Res Monogr. 1989;92:211–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratantonio J, Andrade L, Febo M. Designer Drugs: A Synthetic Catastrophe. Journal of Reward Deficiency Syndrome. 2015;1(2):82–86. doi: 10.17756/jrds.2015-014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatch MB, Dolan SB, Forster MJ. Comparative behavioral pharmacology of three pyrrolidine-containing synthetic cathinone derivatives. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2015;354:103–110. doi: 10.1124/jpet.115.223586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayton-Ely M, Shakleya DM, Bell SC. Application of a Pyroprobe to Simulate Smoking and Metabolic Degradation of Abused Drugs Through Analytical Pyrolysis. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 2007;52(2):473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1556-4029.2006.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatsukami DK, Fischman MW. Crack cocaine and cocaine hydrochloride: Are the differences myth or reality? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;276(19):1580–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hueza IM, Ponce F, Garcia RC, Marcourakis T, Yonamine M, Mantovani CDC, Kirsten TB. A new exposure model to evaluate smoked illicit drugs in rodents: A study of crack cocaine. Journal of Pharmacological and Toxicological Methods. 2016;77:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeffcoat AR, Perez-Reyes MARIO, Hill JM, Sadler BM, Cook CE. Cocaine disposition in humans after intravenous injection, nasal insufflation (snorting), or smoking. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 1989;17(2):153–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karila L, Reynaud M. GHB and synthetic cathinones: clinical effects and potential consequences. Drug Testing and Analysis. 2011;3(9):552–559. doi: 10.1002/dta.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavanagh P, O'Brien J, Power JD, Talbot B, McDermott SD. ‘Smoking’ mephedrone: The identification of the pyrolysis products of 4-methylmethcathinone hydrochloride. Drug Testing and Analysis. 2013;5(5):291–305. doi: 10.1002/dta.1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PS, Johnson MW. Investigation of “Bath Salts” Use Patterns Within an Online Sample of Users in the United States. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(5):369–378. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2014.962717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Goldberg SR. Nicotine induces conditioned place preferences over a large range of doses in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2005;178(4):481–492. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusich JA, Antonazzo KR, Blough BE, Brandt SD, Kavanagh PV, Partilla JS, Baumann MH. The new psychoactive substances 5-(2-aminopropyl) indole (5-IT) and 6-(2-aminopropyl) indole (6-IT) interact with monoamine transporters in brain tissue. Neuropharmacology. 2016;101:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2015.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusich JA, Antonazzo KR, Wiley JL, Blough BE, Partilla JS, Baumann MH. Pharmacology of novel synthetic stimulants structurally related to the “bath salts” constituent 3, 4-methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV) Neuropharmacology. 2014;87:206–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusich JA, Grant KR, Blough BE, Wiley JL. Effects of synthetic cathinones contained in “bath salts” on motor behavior and a functional observational battery in mice. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33(5):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto T, Kamijo A, Miyakawa T, Endo K, Yabana T, Kishimoto H, et al. Methamphetamine in Japan: the consequences of methamphetamine abuse as a function of route of administration. Addiction. 2002;97(7):809–817. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKetin R, Ross J, Kelly E, Baker A, Lee N, Lubman D, Mattick R. Characteristics and harms associated with injecting versus smoking methamphetamine among methamphetamine treatment entrants. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2008;27(3):277–285. doi: 10.1080/09595230801919486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Dukat M, Bridgen DT, Martin BR, Lichtman AH. Pharmacological effects of methamphetamine and other stimulants via inhalation exposure. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1999;53(2):111–120. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y, Lichtman AH, Bridgen DT. Inhalation studies with drugs of abuse. NIDA Research Monographs. 1997;173:201–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milesi-Hallé A, Hendrickson HP, Laurenzana EM, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Sex-and dose-dependency in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of (+)- methamphetamine and its metabolite (+)-amphetamine in rats. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2005;209(3):203–213. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS) Sentinel Community Site Profile. Atlanta Metro. 2015a Available at: http://ndews.umd.edu/sites/ndews.umd.edu/files/SCS%20Atlanta%20Metro%202015%20Final%20Web.pdf.

- National Drug Early Warning System (NDEWS) Sentinel Community Site Profile. Southeastern Florida (Miami Area) 2015b Available at: http://ndews.umd.edu/sites/ndews.umd.edu/files/SCS%20Southeastern%20Florida%20%28Miami%20Area%29%202015%20Final%20Web.pdf.

- Psychonaut Research Web Mapping Project. MDPV Report. London, UK: Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Rambousek L, Kacer P, Syslova K, Bumba J, Bubenikova-Valesova V, Slamberova R. Sex differences in methamphetamine pharmacokinetics in adult rats and its transfer to pups through the placental membrane and breast milk. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;139:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickli A, Hoener MC, Liechti ME. Monoamine transporter and receptor interaction profiles of novel psychoactive substances: para-halogenated amphetamines and pyrovalerone cathinones. European Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;25(3):365–376. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Hida M, Nagase H. Analysis of pyrolysis products of methamphetamine. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2004;28(8):638–643. doi: 10.1093/jat/28.8.638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheidweiler KB, Plessinger MA, Shojaie J, Wood RW, Kwong TC. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of methylecgonidine, a crack cocaine pyrolyzate. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2003;307(3):1179–1187. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.055434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schifano F, Albanese A, Fergus S, Stair JL, Deluca P, Corazza O, et al. Mephedrone (4- methylmethcathinone; ‘meow meow’): chemical, pharmacological and clinical issues. Psychopharmacology. 2011;214:593–602. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler CW, Bross JG, Thorndike EB. Gender differences in the behavioral effects of methamphetamine. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2002;442(3):231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)01550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine H, Nakahara Y. Abuse of smoking methamphetamine mixed with tobacco: I. Inhalation efficiency and pyrolysis products of methamphetamine. Journal of Forensic Sciences. 1987;32(5):1271–1280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks KG, Dahn T, Behonick G, Terrell A. Analysis of first and second generation legal highs for synthetic cannabinoids and synthetic stimulants by ultra-performance liquid chromatography and time of flight mass spectrometry. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2012;36(6):360–371. doi: 10.1093/jat/bks047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimosato K, Ohkuma S. Simultaneous monitoring of conditioned place preference and locomotor sensitization following repeated administration of cocaine and methamphetamine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2000;66(2):285–292. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rass O, Pacek LR, Johnson PS, Johnson MW. Characterizing use patterns and perceptions of relative harm in dual users of electronic and tobacco cigarettes. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23(6):494. doi: 10.1037/pha0000050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzschentke TM. Measuring reward with the conditioned place preference paradigm: a comprehensive review of drug effects, recent progress and new issues. Progress in Neurobiology. 1998;56(6):613–672. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(98)00060-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Synthetic Cannabinoids and Cathinones - DEA Request for Information. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control. National Forensic Laboratory Information System: Year 2013 Annual Report. Springfield, VA: U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, Office of Diversion Control. National Forensic Laboratory Information System: Year 2014 Annual Report. Springfield, VA: U S Drug Enforcement Administration; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Risk assessment forum. Washington, DC: U.S. EPA; 1998a. Guidelines for neurotoxicity risk assessment. 630/R-95/001F. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA) Health effects guidelines: neurotoxicity screening battery. Washington, DC: U.S. EPA; 1998b. EPA 712-C-98-238. OPPTS 870.6200. [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Mitcheson LR, Deluca P, Davey Z, Corazza O, Schifano F. Mephedrone, new kid for the chop? Addiction. 2011;106(1):154–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winstock AR, Ramsey JD. Legal highs and the challenges for policy makers. Addiction. 2010;105(10):1685–1687. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zakharova E, Leoni G, Kichko I, Izenwasser S. Differential effects of methamphetamine and cocaine on conditioned place preference and locomotor activity in adult and adolescent male rats. Behavioural Brain Research. 2009;198(1):45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]