Abstract

Objective

We conducted this study to report the efficacy of local application of vancomycin powder in the setting of surgical site infection (SSI) of posterior lumbar surgical procedures and to figure out risk factors of SSIs.

Methods

From February 2013 to December 2013, SSI rates following 275 posterior lumbar surgeries of which intrawound vancomycin powder was used in combination with intravenous antibiotics (Vanco group) were assessed. Compared with 296 posterior lumbar procedures with intravenous antibiotic only group from February 2012 to December 2012 (non-Vanco group), various infection rates were assessed. Univariate and multivariate analysis to figure out risk factors of infection among Vanco group were done.

Results

Statistically significant reduction of SSI in Vanco group (5.5%) from non-Vanco group (10.5%) was confirmed (p=0.028). Mean follow-up period was 8 months. Rate of acute staphylococcal SSIs reduced statistically significantly to 4% compared to 7.4% of non-Vanco group (p=0.041). Deep staphylococcal infection decreased to 2 compared to 8 and deep methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection also decreased to 1 compared to 5 in non-Vanco group. No systemic complication was observed. Statistically significant risk factors associated with SSI were diabetes mellitus, history of cardiovascular disease, length of hospital stay, number of instrumented level and history of previous surgery.

Conclusion

In this series of 571 patients, intrawound vancomycin powder usage resulted in significant decrease in SSI rates in our posterior lumbar surgical procedures. Patients at high risk of infection are highly recommended as a candidate for this technique.

Keywords: Surgical wound infection, Vancomycin, Topical administration, Staphylococcal infection

INTRODUCTION

As well known, surgical site infection (SSI) following spine surgery is devastating with significant increase in hospital stay, health care costs and morbidities3,9). Though incidence is reported to be ranging from 1.9%-13%, these days, SSIs are the most frequent hospital-acquired infection outweighing urinary catheter infections, ventilator acquired pneumonias, central line-related infections, and Clostridium difficile infections2,8,15,16,19,21). Most of these SSIs require additional surgical treatments for exploration, sampling and debridement.

In spine surgery, operative wound infections are known to be caused by gram-positive organisms, primarily Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis10,20). Correspondingly, usage of broad spectrum antimicrobial drugs such as cefazolin has been a routine practice to prevent SSI for several decades13,27). Lamentably, the proportion of infections caused by methicillin-resistant staphylococci has been rising, thus decreasing the efficacy of cephalosporins for preventing SSIs26).

Both patient-related and operation-related risk factors contribute to the development of SSIs. Patient-related risk factors include obesity, diabetes and an immunocompromised state, while operation-related factors consist of multilevel surgery, use of instrumentation, revision surgery, and large intraoperative blood loss4,17,18).

Recently, direct use of intrawound vancomycin powder has shown to decrease SSI rates14,16,25). The aim of present study is to assess incidence, risk factors and outcome of SSIs between patients with or without local intrawound vancomycin powder at the surgical site, in addition to standard intravenous prophylaxis. And also, to evaluate risk factors for SSI in setting of local vancomycin instillation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patients and Study Design

All operative procedures were performed by 2 senior surgeons (KHB and HJC) in a single center. From February 2012 to December 2013, consecutive 571 patients undergoing posterior lumbar surgery at Hanyang University Medical Center were enrolled in the present study. Patients were selected according to following inclusion and exclusion criteria. We reviewed the medical charts and radiographic materials of the above patients, retrospectively.

Patients were divided into 2 groups according to the date of operation. Prior to February of 2013, all patients undergoing posterior lumbar surgery received standard prophylactic intravenous antibiotics only. Beginning in February of 2013, all patients undergoing posterior lumbar surgery received between 1 g of vancomycin powder applied directly to the wound just prior to closure, in addition to standard prophylactic intravenous antibiotics.

2. Exclusion Criteria

Following patients were excluded from this analysis: (1) previous history of infections at the surgical site; (2) biopsy procedure; (3) patients with a postoperative follow-up time of less than 12 weeks; (4) patients allergic to vancomycin; (5) patients undergoing minimal invasive spine surgery; (6) surgery due to trauma related lesions.

3. Variables and Data Sources

Following selection of patients, their data were collected including patients' status, operative characteristics and demographic factors.

Patients' status included mean American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade and hospitalized days until discharge or SSI development. Operative characteristics included presence of previous surgery, postoperative diagnosis, hemovac drain usage, operative time, number of levels instrumented, whether decompressed or not and estimated blood loss (mL). Demographic factors assessed patient's sex, age, adult body mass index (BMI) and medical comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, history of respiratory and cardiovascular disease, and smoking habit).

Other measures including number of neurosurgical residents involved in the surgery and method of hair removal (whether clipper or razor usage) were indifferent between 2 groups. Massive surgical site irrigation with normal saline and double glove technique were routinely used in all operative procedures

4. Protocols

Standard prophylactic intravenous antibiotics for spinal surgery included 2 g of cefotetan given intravenously within one hour prior to incision and with repeat dosing every 4 hours during surgery. Postoperatively, patients were given 2 g of cefotetan intravenously every 12 hours for 5 days.

We defined an SSI as an infection occurring within 12 weeks following the operation, requiring an additional operation (i.e., an irrigation and debridement) and having positive wound cultures. Infections were further subdivided into superficial (occurring above the lumbosacral fascia) or deep (beneath the lumbosacral fascia) based on the wound culture reports and operative reports.

5. Statistical Analysis

Variables suitable for nominal scale were converted into categorical variables by dichotomization. The chi-square, Fisher exact test were used when appropriate for group comparisons. Categorized data (gender, age, obesity [adult BMI above 25 kg/m2], hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, history of respiratory diseases and cardiovascular diseases, estimated blood loss over 1,000mL, whether decompression was done or not, history of previous surgery, usage of hemovac) were analyzed using Fisher exact and/or chi-square tests. ASA score, length of hospital stay, operative time and number of level instrumented were analyzed using independent t-test. Univariate analysis was performed to determine associations between the SSI and potential covariates. Covariates with a p-value of <0.05 were entered into a binary logistic regression. We considered a p-value of <0.05 to be significant for all analyses.

RESULTS

1. Patient Characteristics

Since February 2012 to December 2013, total 693 consecutive posterior lumbar surgeries have been performed. Among them, 122 patients were excluded due to trauma-related lesions (n=96), loss of follow-up within 12 weeks (n=17), biopsy procedure (n=3), allergic to vancomycin (n=2), and history of infection (n=4).

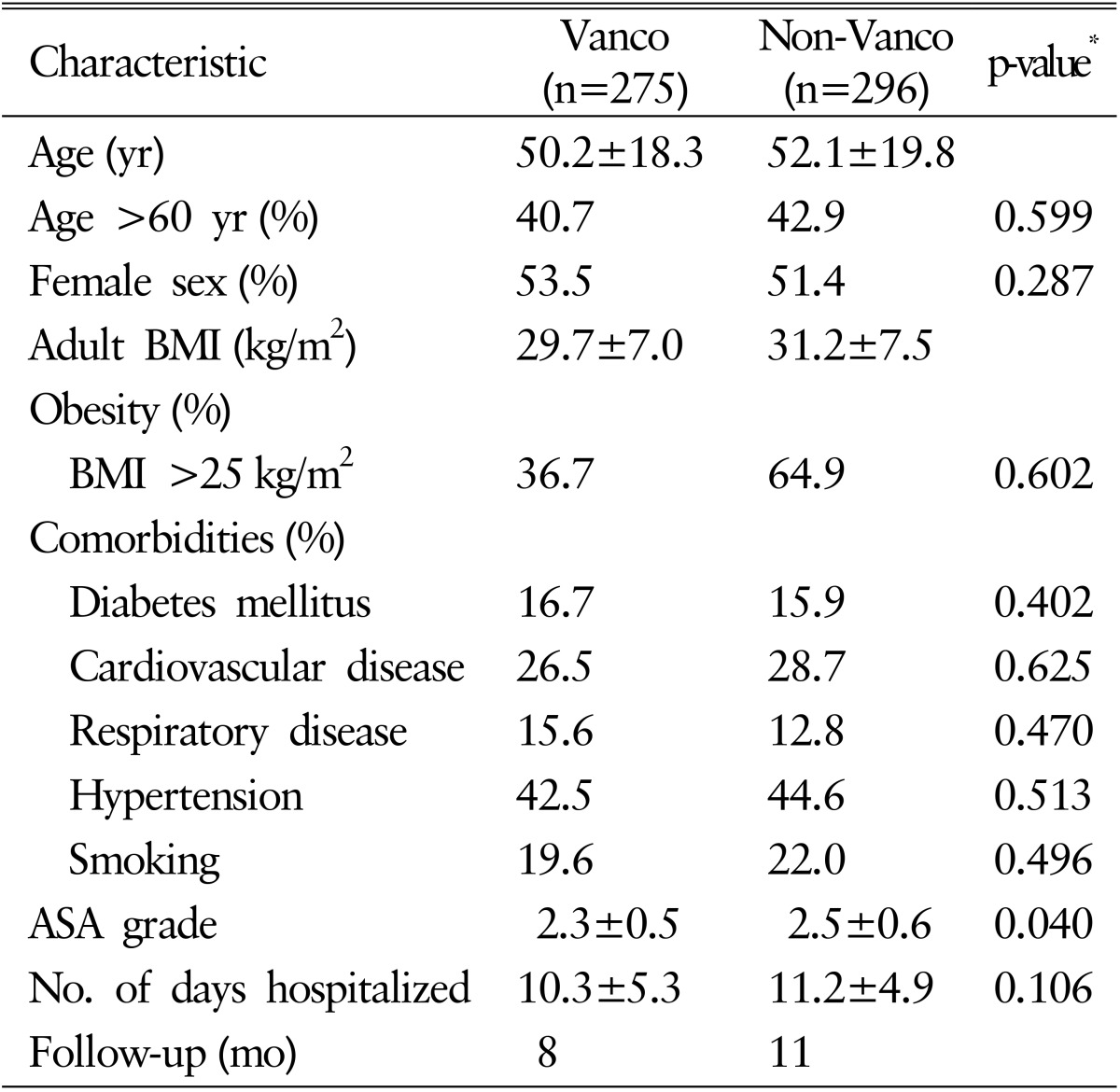

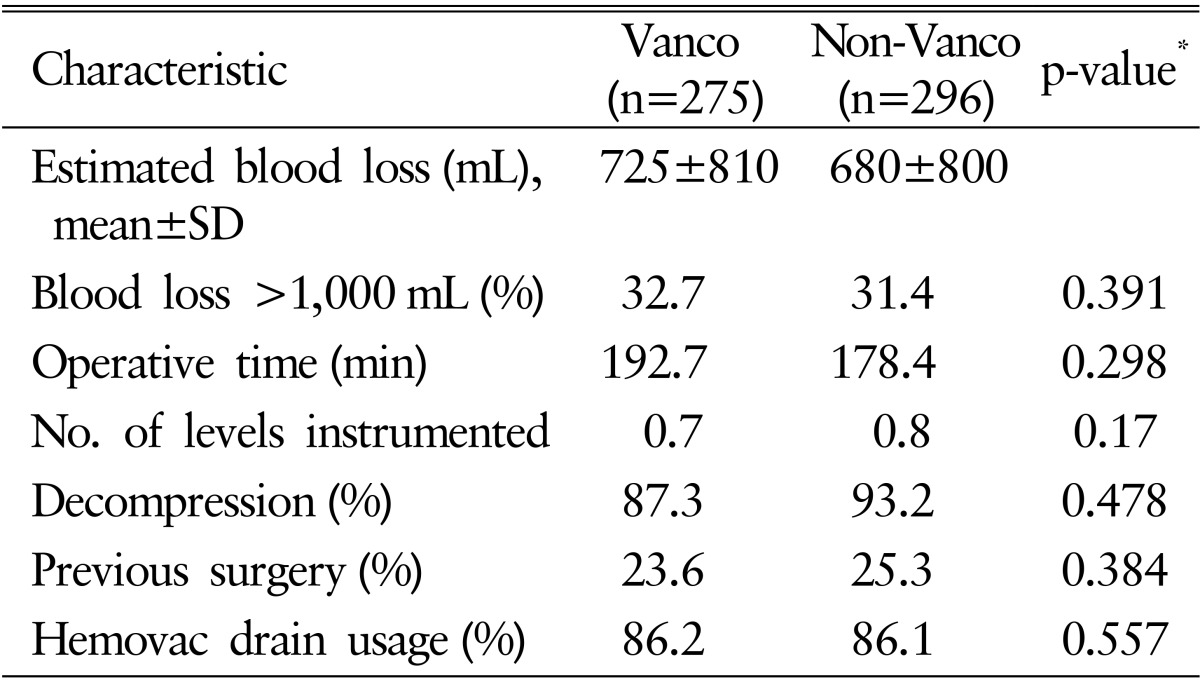

The patient group who underwent surgery from February 2013 to December 2013 and received intrawound vancomycin powder in addition to the standard antimicrobial prophylaxis was defined as Vanco group (n=275). The other group who had surgery from February 2012 to December 2012 and did not receive intrawound vancomycin powder was named as non-Vanco group (n=296). Demographic factors of patients did not show significant difference between 2 groups except mean ASA grade (p<0.05). Operative data also were unable to show statistical significant difference between the 2 groups. The summaries of demographic and operative data are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of patients with or without intrawound vancomycin (Vanco) powder.

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation unless otherwise indicated.

BMI, body mass index; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

*t-test.

Table 2. Operative characteristics of patients with or without intrawound vancomycin (Vanco) powder.

SD, standard deviation.

*t-test.

2. Incidence of SSIs

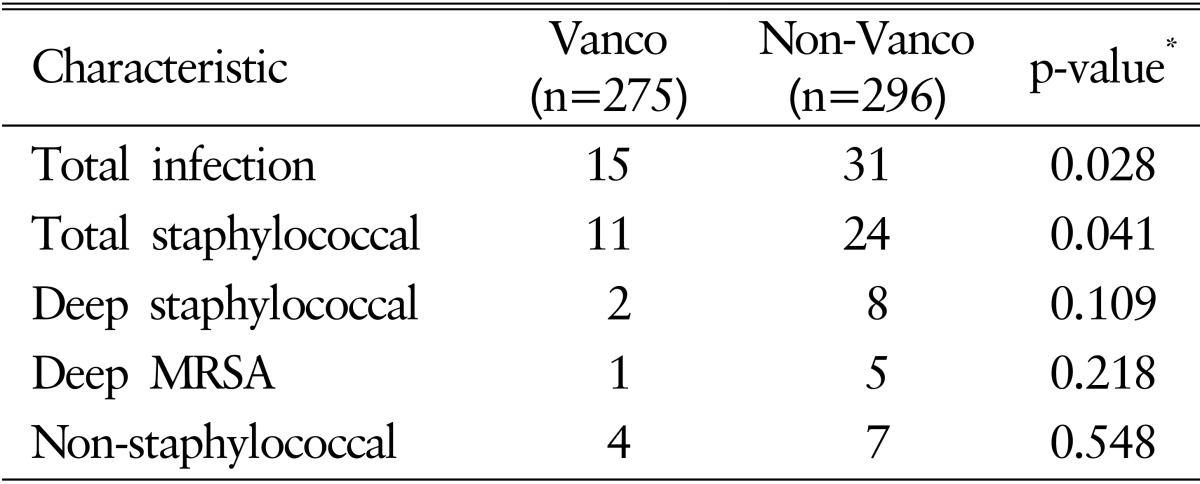

Among 571 patients, the overall incidence of SSIs was 8.1% (46 of 571). Total staphylococcal infection was present in 33 patients (5.8%) with deep methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus(MRSA) infection in 6 patients and deep staphylococcal infection in 10 patients. N onstaphylococcal infection was found in 11 patients (1.9%). In Vanco group, staphylococcal infection was present in 11 patients with deep MRSA infection in 1 case. Nonstaphylococcal infection was observed in 4 patients. In total, 15 patients presented with SSIs in Vanco group. On the other hand, in non-Vanco group, acute SSIs developed in total of 29 patients, 8 of which were staphylococcal infection. Deep MRSA infection was confirmed in 5 patients and nonstaphylococcal infection was found in 7 patients. When 2 groups are compared using chi-square or Fisher exact test, total infection rate and total staphylococcal infection rate showed statistically significant difference (p=0.028 and p=0.041, respectively). The infection rates and statistical analysis are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Rates of infections.

Vanco, vancomycin; MRSA, Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

*Chi-square/Fisher exact text.

3. Outcome

After surgery, perioperative complications regarding neuritis, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, pseudoarthrosis rate, implant failure, return to the operating room did not show significant difference between the 2 groups. Meanwhile, common adverse effect of vancomycin powder such as hypotension and renal toxicity was not observed in Vanco group.

4. Risk Factors

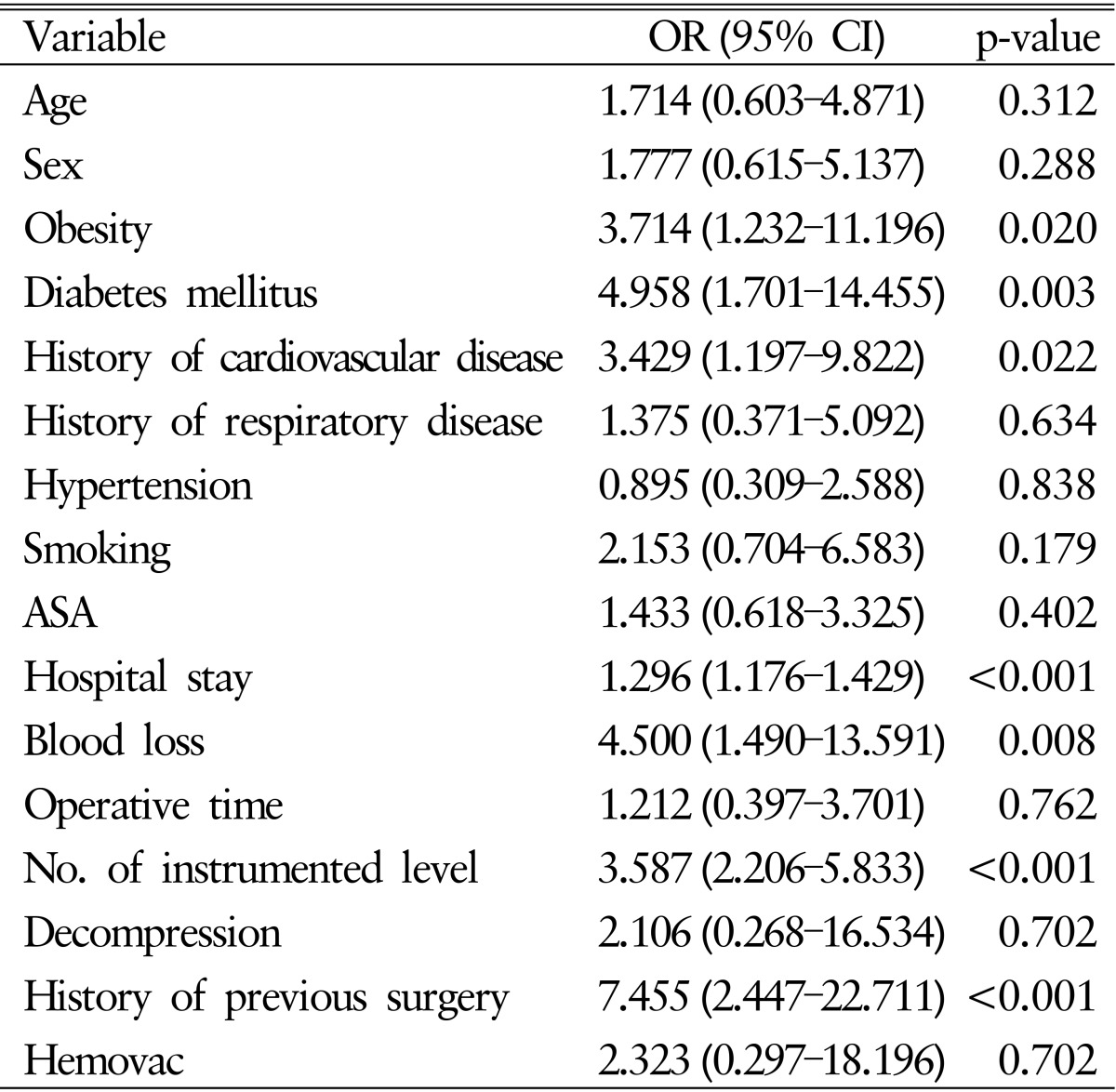

In the univariate analysis of potential risk factors for acute SSIs among Vanco group, statistically significant risk factors were obesity (odds ratio [OR], 3.714; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.232-11.196), diabetes mellitus (OR, 4.958; 95% CI, 1.701-14.455), history of cardiovascular disease (OR, 3.429; 95% CI, 1.197-9.822), length of hospital stay (OR, 1.296; 95% CI, 1.176-1.429), loss of blood during surgery over 1,000mL (OR, 4.500; 95% CI, 1.490-13.591), number of instrumented levels (OR, 3.587; 95% CI, 2.206-5.833) and history of previous surgery (OR, 7.455; 95% CI, 2.447-22.711).

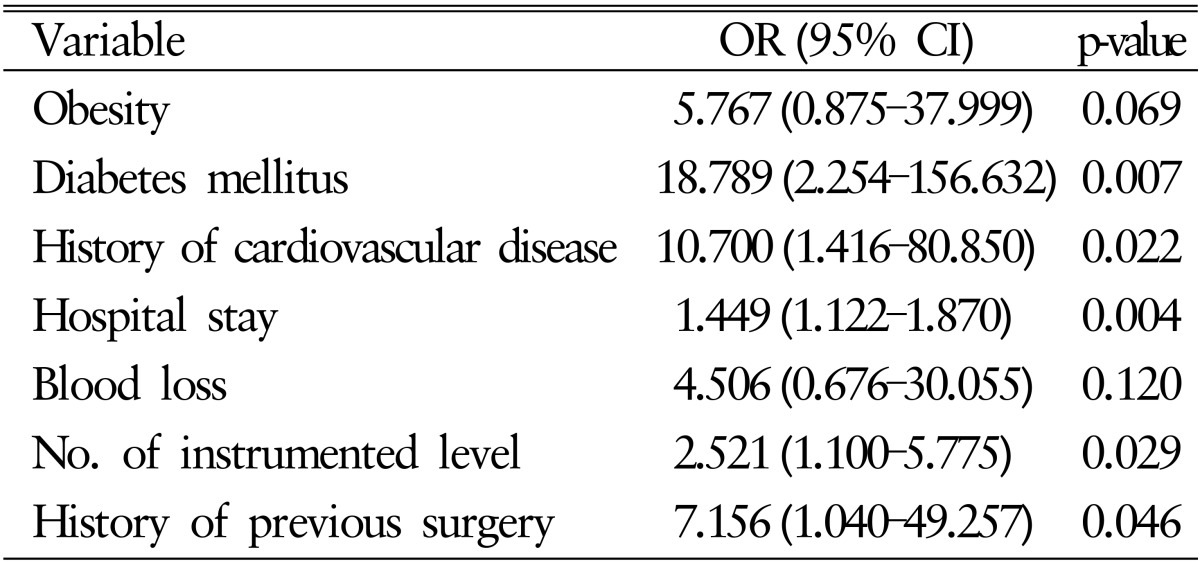

In the multivariate analysis using binary logistic regression model, diabetes mellitus (OR, 18.787; 95% CI, 2.254-156.632), history of cardiovascular disease (OR, 10.700; 95% CI, 1.416-80.850), length of hospital stay (OR, 1.449; 95% CI, 1.122-1.870), number of instrumented levels (OR, 2.521; 95% CI, 1.100-5.775) and history of previous surgery (OR, 7.156; 95% CI, 1.040-49.257) were statistically significant risk factors increasing the risk of acute SSIs. Detailed univariate and multivariate statistical analysis are presented in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

Table 4. Univariate statistical analysis of potential risk factors.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists.

Table 5. Multivariate statistical analysis of potential risk factors.

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

DISCUSSION

1. Incidence of SSIs

Our study was designed to clarify incidence, risk factors and outcome of SSIs between intrawound vancomycin applied group and nonvancomycin group. Our incidence of overall SSIs was 7.7%(44 of 571): Vanco group 5.5%(15 of 275) and non-Vanco group 9.8%(29 of 296). Though addition of superficial infection to analysis might have influenced infection rate of our study higher than others, this rate is in line with other reports which reported incidence of SSIs between 2.8% and 10% after instrumented thoracolumbar spine fusion without use of topical vancomycin powder1,6,12,19,24).

When limiting the result to the deep infection rate, study done by Scoliosis Research Society Morbidity and Mortality Committee reported deep infection rate of 1.3% among 108,419 surgical cases though adjunctive measures for infection prophylaxis were not considered23). Molinari et al.14) reported deep wound infection rate of 1.2% for instrumented spinal surgery and 0.82% for uninstrumented surgeries. One of most meaningful studies done by Sweet et al.25) have shown deep infection rate of 2.6% among non-Vanco group compared to 0.2% in Vanco group though result is limited to posterior instrumented thoracic and lumbar spinal arthrodesis. As in other studies, our study demonstrated statistically significant decrement in postoperative deep infection rates with application of intrawound vancomycin powder.

2. Mechanism of Intrawound Vancomycin Powder

One of the important causes for postoperative spinal infection is intraoperative contamination of wounds11). Hence, antibiotics and surgical wound irrigation have been a routine perioperative measures throughout various hospitals. In addition, to reduce SSI, various techniques including topical wound antibiotic instillation, closed wound suction drainage, shaving, silver dressings and wound irrigation with 0.35% povidoneiodine solution have been tested. None have proved superior to others except the use of betadine solution which showed some moderate evidence in preventing SSI22).

Lately, the efficacy of prophylactic intraoperative instillation of vancomycin is becoming a matter of interest for many clinicians undergoing spinal surgery due to emerging spinal infection. Vancomycin has been selected as prophylactic topical antibiotic of choice due to its cost-effectiveness, easy-to-use powdered form, and its effective broad coverage against organisms such as MRSA.

Sweet et al.25) have demonstrated that intrawound vancomycin powder is not readily absorbed into the systemic circulation, but rather stays in the wound and acts locally to prevent infection. Also, Gans et al.5) reported systemic level of vancomycin lower than 2.0 µg/mL in 49 out of 50 patients which is lower than level required to cause systemic toxicitiy. This may be largely due to large molecular size of vancomycin, thus interrupting vancomycin from absorbed systematically7). Zebala et al.28) conducted in vivo rabbit study by comparing vancomycin and control group which injected S. aureus into the wound after surgery and concluded that intrawound vancomycin concentration was high enough to defeat known staphylococcal infection.

Our study supports conclusions of above mentioned studies because reduction of SSI was effectively achieved and no side effect due to vancomycin was observed.

3. Risk Factors for SSIs

Risk factors for SSI in spine surgery have long been a matter of interest and can be divided into patient factors and surgical factors4,5,7,12,17,24). Patient risk factors include advanced patient age, obesity, diabetes, urinary incontinence, smoking, and malnutrition. Surgical risk factors are composed of revision surgery, increased surgical blood loss, prolonged surgical time, use of instrumentation, and multilevel posterior fusions.

In our study, risk factors associated with development of SSI were diabetes mellitus, hypertension, history of previous surgery, length of hospital stay, and level of instrumentation. In context of patient factors, diabetes, hypertension, history of previous surgery, and length of hospital stay were statistically significant factors. Surgical factor was number of level instrumented.

4. Limitations

Our study has a limitation in that it is retrospectively designed. Lack of measurement in blood/wound vancomycin level could be weakness of our study. Also, deep MRSA and deep staphylococcal infection rates failed to show statistically significant reduction between the Vanco and non-Vanco groups. This may well be explained by small sample size. Thus, further investigation on larger group study should be conducted to confirm the actual difference between the 2 groups.

CONCLUSION

In this series of 571 patients, intrawound vancomycin powder usage resulted in significant decrease in SSI rates in our posterior lumbar surgical procedures. Presence of diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and longer hospital stay were statistically significant risk factors associated with SSI. Patients at high risk of infection are highly recommended as a candidate for this technique.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Borkhuu B, Borowski A, Shah SA, Littleton AG, Dabney KW, Miller F. Antibiotic-loaded allograft decreases the rate of acute deep wound infection after spinal fusion in cerebral palsy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2008;33:2300–2304. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818786ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins I, Wilson-MacDonald J, Chami G, Burgoyne W, Vineyakam P, Berendt T, et al. The diagnosis and management of infection following instrumented spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 2008;17:445–450. doi: 10.1007/s00586-007-0559-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engemann JJ, Carmeli Y, Cosgrove SE, Fowler VG, Bronstein MZ, Trivette SL, et al. Adverse clinical and economic outcomes attributable to methicillin resistance among patients with Staphylococcus aureus surgical site infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:592–598. doi: 10.1086/367653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fang A, Hu SS, Endres N, Bradford DS. Risk factors for infection after spinal surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:1460–1465. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000166532.58227.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gans I, Dormans JP, Spiegel DA, Flynn JM, Sankar WN, Campbell RM, et al. Adjunctive vancomycin powder in pediatric spine surgery is safe. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:1703–1707. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31829e05d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodges SD, Humphreys SC, Eck JC, Covington LA, Kurzynske NG. Low postoperative infection rates with instrumented lumbar fusion. South Med J. 1998;91:1132–1136. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Humphrey JS, Mehta S, Seaber AV, Vail TP. Pharmacokinetics of a degradable drug delivery system in bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;349:218–224. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199804000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan NR, Thompson CJ, DeCuypere M, Angotti JM, Kalobwe E, Muhlbauer MS, et al. A meta-analysis of spinal surgical site infection and vancomycin powder. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;21:974–983. doi: 10.3171/2014.8.SPINE1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kirkland KB, Briggs JP, Trivette SL, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. The impact of surgical-site infections in the 1990s: attributable mortality, excess length of hospitalization, and extra costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:725–730. doi: 10.1086/501572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee DG, Park KB, Kang DH, Hwang SH, Jung JM, Han JW. A clinical analysis of surgical treatment for spontaneous spinal infection. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2007;42:317–325. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2007.42.4.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lonstein J, Winter R, Moe J, Gaines D. Wound infection with Harrington instrumentation and spine fusion for scoliosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1973;96:222–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Massie JB, Heller JG, Abitbol JJ, McPherson D, Garfin SR. Postoperative posterior spinal wound infections. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;284:99–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeod LM, Keren R, Gerber J, French B, Song L, Sampson NR, et al. Perioperative antibiotic use for spinal surgery procedures in US children's hospitals. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:609–616. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e318289b690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Molinari RW, Khera OA, Molinari WJ., 3rd Prophylactic intraoperative powdered vancomycin and postoperative deep spinal wound infection: 1,512 consecutive surgical cases over a 6-year period. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(Suppl 4):S476–S482. doi: 10.1007/s00586-011-2104-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Muilwijk J, Walenkamp GH, Voss A, Wille JC, van den Hof. Random effect modelling of patient-related risk factors in orthopaedic procedures: results from the Dutch nosocomial infection surveillance network ‘PREZIES’. J Hosp Infect. 2006;62:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Neill KR, Smith JG, Abtahi AM, Archer KR, Spengler DM, McGirt MJ, et al. Reduced surgical site infections in patients undergoing posterior spinal stabilization of traumatic injuries using vancomycin powder. Spine J. 2011;11:641–646. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2011.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen MA, Mayfield J, Lauryssen C, Polish LB, Jones M, Vest J, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection in spinal surgery. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(2 Suppl):149–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olsen MA, Nepple JJ, Riew KD, Lenke LG, Bridwell KH, Mayfield J, et al. Risk factors for surgical site infection following orthopaedic spinal operations. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:62–69. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rechtine GR, Bono PL, Cahill D, Bolesta MJ, Chrin AM. Postoperative wound infection after instrumentation of thoracic and lumbar fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:566–569. doi: 10.1097/00005131-200111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasso RC, Garrido BJ. Postoperative spinal wound infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:330–337. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200806000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schimmel JJ, Horsting PP, de Kleuver M, Wonders G, van Limbeek J. Risk factors for deep surgical site infections after spinal fusion. Eur Spine J. 2010;19:1711–1719. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1421-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuster JM, Rechtine G, Norvell DC, Dettori JR. The influence of perioperative risk factors and therapeutic interventions on infection rates after spine surgery: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010;35(9 Suppl):S125–S137. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d8342c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith JS, Shaffrey CI, Sansur CA, Berven SH, Fu KM, Broadstone PA, et al. Rates of infection after spine surgery based on 108,419 procedures: a report from the Scoliosis Research Society Morbidity and Mortality Committee. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:556–563. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181eadd41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sponseller PD, LaPorte DM, Hungerford MW, Eck K, Bridwell KH, Lenke LG. Deep wound infections after neuromuscular scoliosis surgery: a multicenter study of risk factors and treatment outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2461–2466. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200010010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sweet FA, Roh M, Sliva C. Intrawound application of vancomycin for prophylaxis in instrumented thoracolumbar fusions: efficacy, drug levels, and patient outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;36:2084–2088. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ff2cb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tubaki VR, Rajasekaran S, Shetty AP. Effects of using intravenous antibiotic only versus local intrawound vancomycin antibiotic powder application in addition to intravenous antibiotics on postoperative infection in spine surgery in 907 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38:2149–2155. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams DN, Gustilo RB, Beverly R, Kind AC. Bone and serum concentrations of five cephalosporin drugs. Relevance to prophylaxis and treatment in orthopedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;179:253–265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zebala LP, Chuntarapas T, Kelly MP, Talcott M, Greco S, Riew KD. Intrawound vancomycin powder eradicates surgical wound contamination: an in vivo rabbit study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:46–51. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]