Abstract

Exposure to persistent organic pollutants, including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) is correlated with multiple vascular complications including endothelial cell dysfunction and atherosclerosis. PCB-induced activation of the vasculature subsequently leads to oxidative stress and induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines and adhesion proteins. Gene expression of these cytokines/proteins is known to be regulated by small, endogenous oligonucleotides known as microRNAs that interact with messenger RNA. MicroRNAs are an acknowledged component of the epigenome, but the role of environmentally-driven epigenetic changes such as toxicant-induced changes in microRNA profiles are currently understudied. The objective of this study was to determine the effects of PCB exposure on microRNA expression profile in primary human endothelial cells using the commercial PCB mixture Aroclor 1260. Samples were analyzed using Affymetrix GeneChip® miRNA 4.0 arrays for high throughput detection and selected microRNA gene expression was validated (RT-PCR). Microarray analysis identified 557 out of 6658 microRNAs that were changed with PCB exposure (p <0.05). In-silico analysis using MetaCore database identified 21 of these microRNAs to be associated with vascular diseases. Further validation showed that Aroclor 1260 increased miR-21, miR-31, miR-126, miR-221 and miR-222 expression levels. Upregulated miR-21 has been reported in cardiac injury while miR-126 and miR-31 modulate inflammation. Our results demonstrated evidence of altered microRNA expression with PCB exposure, thus providing novel insights into mechanisms of PCB toxicity.

Keywords: Aroclor 1260, PCBs, miRNAs, vascular diseases, endothelial cells

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small, endogenous, non-coding RNAs (~22-25 nucleotides long) that have recently been shown to play a critical role in regulating gene expression and protein production (Bartel, 2004). Ever since their discovery in the early 90's, over 1000 miRNAs have been identified in the human genome, and these miRNAs are predicted to regulate approximately 30% of the human protein-coding genome (Ardekani and Naeini, 2010). Traditionally, miRNAs were thought to be negative regulators of gene expression (RNA silencing) that act either by base pairing with complementary sequences on the mRNA transcript and promoting its degradation or by repressing translation (Bartel, 2004). However, emerging studies have demonstrated that miRNAs can also positively regulate gene expression by targeting promoter sequences of specific genes (Place et al., 2008). Because of their regulatory role, miRNAs have the ability to regulate biological and physiological processes such as cell proliferation, differentiation, metastasis, inflammation and apoptosis. In fact, the pivotal role of miRNAs in influencing the development and progression of diseases is becoming increasingly recognized (Li and Kowdley, 2012). Changes in miRNA profile can be induced by pathophysiology or exposure to environmental stimuli that eventually results in altered cellular responses, making these molecules potential biomarkers for disease prognosis and diagnosis as well as targets for therapeutic implications (Duong Van Huyen et al., 2014; Srinivasan et al., 2013). Advances in oligonucleotide microarrays and next generation sequencing technologies have enabled the entire miRNAome to be analyzed. Altered miRNA expression profile has been implicated in almost all cancer types (Pichler and Calin, 2015); however, the role of these noncoding molecules is not limited to neoplasia but extends to other pathologies including vascular diseases and cardiac complications, neuro-developmental diseases and liver diseases (Chang et al., 2016; Fernandez-Hernando and Baldan, 2013; Kim and Kim, 2014; Pirola et al., 2015).

Cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are the primary cause of mortality and morbidity in developed countries and includes atherosclerosis, vascular inflammation and endothelial cell dysfunction among other complications (Pagidipati and Gaziano, 2013). These pathological states are accompanied by modified expression profile of genes associated with cardiac function/inflammation such as vascular cell adhesion molecules e.g. (VCAM-1, ICAM-1) and cytokines. Interestingly, with the advent of miRNA research, multiple studies have shown that cellular homeostasis of these CVD-related genes is regulated by specific miRNAs (Fernandez-Hernando and Baldan, 2013; Ono et al., 2011; Small et al., 2010). Our laboratory has previously demonstrated that exposure to environmental toxicants such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) caused endothelial cell dysfunction by activating the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), subsequently leading to induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, adhesion proteins and cytochrome P450s (Arzuaga et al., 2007; Petriello et al., 2014).

PCBs are persistent organic pollutants that were commercially manufactured and used mainly as dielectric fluids in electrical transformers. Epidemiologic studies have correlated PCB exposure with multiple health complications such as liver injury, hypertension and vascular inflammation (Cave et al., 2010; Perkins et al., 2016). PCBs have been shown to interact with a myriad of receptors in the body including the AhR and hepatic nuclear receptors, and this has been attributed as a mechanism of PCB-induced toxicity (Luthe et al., 2008; Wahlang et al., 2014). Furthermore, these receptors are intimately involved in maintaining energy homeostasis, cell proliferation, differentiation and inflammation by activating their target gene battery. Importantly the gene expression of these receptors and their target genes may also be under the regulatory control of miRNAs. However, literature regarding which miRNAs are affected with exposure to environmental chemicals such as PCBs is still scarce. We therefore hypothesize that PCBs can induce changes in miRNA profiles in endothelial cells that potentially affect downstream protein turnover. In order to test our hypothesis, we utilized microarray technology for evaluation and the MetaCore database for data interpretation. This could potentially be a new mechanism of action for PCB-induced toxicity in the vasculature.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Aroclor 1260 was purchased from AccuStandard (New Haven, CT, USA). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and ethyl alcohol were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Chloroform and 2-propanol were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH, USA).

2.2. Cell culture

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, 10-donor pool) were obtained from Lifeline Cell Technology (Walkersville, MD, USA). Cells were maintained in VascuLife Basal Medium supplemented with components of the VascuLife VEGF LifeFactors Kit (containing Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor, 2% fetal bovine serum and other appropriate life factors) and 1% antimicrobial supplement (penicillin, streptomycin and amphotericin B). The cells were incubated in a 5% carbon dioxide atmosphere and 95% humidity at 37 °C in T75 flasks and fresh media was added every 2 days. Cells were passaged at 80% confluence. Before passaging, cells were washed with 10 mL of sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and incubated with 6 mL of Lifeline's 0.05% Trypsin/0.02% EDTA for 3 minutes. Then, 6 mL of Lifeline's Trypsin Neutralizing Medium was added to the cells. The entire 12 mL was collected and centrifuged at 150 × g for 5 minutes. The liquid above the cell pellet was aspirated, and cells were resuspended in fresh medium and seeded in 6-well plates.

In order to choose an incubation time for the study, HUVECs were initially exposed to Aroclor 1260 for either 12, 16 or 24 hours and assessed for Cyp1A1 (an AhR target gene) as well as miR-21 induction. The concentrations of Aroclor used for these preliminary studies were 1, 5 and 10 μM. The 12 h incubation did not significantly induce miR-21 even at 10 μM while the 24 h incubation elicited a biphasic concentration-response with CYP1A1 induction. Because the study primarily focused on miRNA induction with PCB exposure, without taking into account factors such as time and concentration dependence, the 16 h time point was chosen.

2.3. RNA isolation

For microarray analysis, cells were harvested after a 16 h exposure to Aroclor 1260. RNA was extracted using the mirVana™ miRNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) to obtain high quality intact RNA that includes the low molecular weight RNA, using an efficient glass fiber filter-based method. The RNA integrity was determined on the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). All samples had an RNA integrity number (RIN) >9. For real time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), cells were harvested and RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc). RNA purity and quantity were assessed with the NanoDrop 2000/2000c (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc) using the NanoDrop 2000 (Installation Version 1.6.198) software.

2.4. Microarray studies

500 ng of total RNA was labeled using Affymetrix Flashtag Biotin HSR RNA Labeling kit (P/N 901910, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The labelling process begins with a brief tailing reaction followed by ligation of the biotinylated signal molecule to the target RNA sample. 450ng of biotin labeled RNA was hybridized to Affymetrix GeneChip® miRNA 4.0 Arrays at 48 °C and 60 rpm for 16-18 h. The chip contains miRNAs and pre-miRNAs that covers 100% of the miRBase version 20 database. Each array contains 30,434 total mature miRNA probe sets. The arrays were washed and stained using the Hybridization Wash and Stain Kit in the 450 Fluidics Station (Affymetrix). Chips were scanned using the Affymetrix GeneChip 7G scanner to acquire fluorescent images of each array. Data were collected using Affymetrix Command Console Software. The data discussed in this study have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus which is accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE79005.

2.5. Real-time PCR

Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from total RNA using the QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA). PCR was performed on the CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using the Taqman Fast Advanced Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc). Primer sequences from Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc) were as follows: actin, beta (ACTB); (Hs01060665_g1), miR-21; (Hs04231424_s1), miR-31; (Hs04231431_s1), miR-126; (Hs04273250_s1), miR-221; (Hs04231481_s1), and miR-222; (Hs04415495_s1). The levels of mRNA were normalized relative to the amount of ACTB mRNA, and expression levels in cells that were not exposed to PCBs were set at 1. Gene expression levels were calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

2.6. In-silico network analysis

The miRNAs that were determined to be statistically altered due to PCB treatment were filtered by selecting only the annotated miRNAs using miRBase v21 database. Target gene information was obtained using TargetScan, miRDB (predicted targets) and TARBASE (validated targets). The mir2disease database and Human microRNA Disease Database (v2.0) were initially utilized to identify miRNAs related to vascular diseases by using the search term ‘vascular diseases’ or ‘cardiovascular diseases’. The miRNAs that were correlated to vascular diseases were also identified using MetaCore (Thomson Reuters, New York City, NY, USA). MetaCore is an integrated software suite for functional analysis of microarray, siRNA, Next Generation Sequencing, proteomics, miRNA, and screening data. A single-network pathway was then built for selected miRNAs to find the shortest path that link a miRNA-mRNA pair. The analysis was ran in MetaBase using the homo sapiens data. MetaBase is an integrated database that MetaCore utilizes and it houses over 6 million experiment findings related to mammalian biology.

2.7. Data and statistical analysis

The CEL files generated by the arrays were processed using the Affymetrix Expression Console Software. The human probe sets were selected and reported in the analysis output. A two sample t-tests was used to compare the two groups for each miRNA. For other data, results were expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism version 6.07 for Windows (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Multiple group data were compared using One Way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post-hoc test. p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The heat map was generated using the Partek Genomics Suite v6.6 software. All studies were overseen by biostatisticians at the University of Kentucky.

3. Results

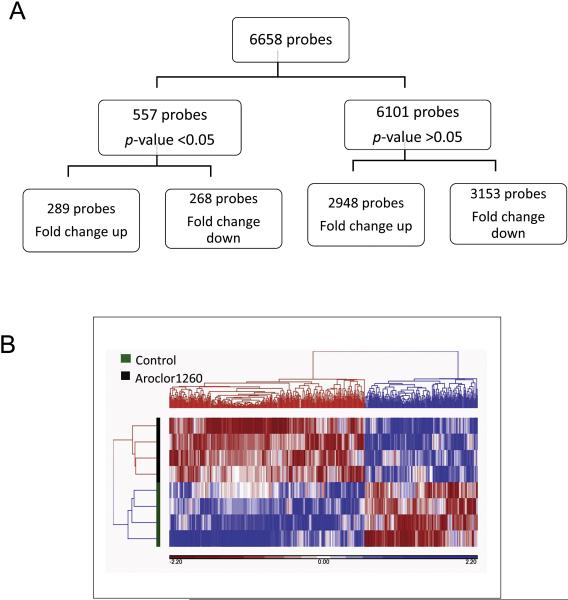

3.1. Aroclor 1260 altered the microRNA profile in HUVECs

To determine the effects of the PCB mixture Aroclor 1260 on the miRNA expression profile in HUVECs, cells were exposed to either the vehicle control (DMSO) or Aroclor 1260 (10 μM) for 16 h. In preliminary studies, Aroclor 1260 at 10 μM significantly induce Cyp1A1 (an AhR target gene) and miR-21 (versus 1 μM or 5 μM). Moreover, a similar concentration for Aroclor 1260 has been used in previous in vitro transfection studies (Wahlang et al., 2014). The 16 h time-point was chosen based on preliminary studies that evaluate if Aroclor 1260 exposure could induce significant changes in miRNA expression at 12, 16 and 24 h. The Affymetrix GeneChip® miRNA 4.0 Array detected over 6000 small non-coding RNAs or probes in the control and Aroclor 1260-exposed samples. The miRNA expression profile in the Aroclor 1260-exposed cells was significantly different from the unexposed cells (Fig. 1 A & B). Out of the 6658 probes detected, 557 probes (402 of these probes are registered in the miRBase v21 database) were either upregulated (289 probes) or downregulated (268 probes) with Aroclor 1260 exposure (p <0.05) versus unexposed cells.

Figure 1.

A. Exposure to the PCB mixture Aroclor 1260 at 10 μM altered the miRNA profile in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs). The HUVECs used were from a 10-donor pool and the cells were divided into Aroclor 1260-exposed group versus unexposed group (control group), n=4. B. Heat map representing color-coded expression levels of differentially expressed miRNAs after hierarchical clustering. The heat map illustrates the unsupervised hierarchical clustering of the microarray data with p <0.05. Deeper red is associated with decreased relative gene expression; deeper blue is associated with greater relative gene expression. Analysis was performed using Partek Genomics Suite software.

Multiple databases were used to identify miRNAs associated with vascular diseases including MetaCore, mir2disease database and Human microRNA Disease Database and only the annotated miRNAs (miRBase) were selected (Table 1 a & b). Search results reported a total of 98 miRNAs associated with vascular diseases using the aforementioned databases and 21 of these miRNAs had altered expression levels with Aroclor 1260 exposure in HUVECs (Table 2).

Table 1a.

List of miRNAs associated with vascular diseases obtained from the mir2disease and human microRNA disease databases. Bold represents miRNAs that were not present in the MetaCore database.

| www.mir2disease.org | ||

|---|---|---|

| miRNA | Relationship type | Expression Pattern |

| hsa-miR-133a | Unspecified | down-regulated |

| hsa-miR-21 | Causal | up-regulated |

| hsa-miR-214 | Unspecified | up-regulated |

| hsa-miR-143 | Unspecified | down-regulated |

| hsa-miR-347 | Unspecified | down-regulated |

| hsa-miR-352 | Unspecified | up-regulated |

| hsa-miR-365 | Unspecified | down-regulated |

| hsa-miR-125a | Unspecified | down-regulated |

| hsa-miR-125b | Unspecified | down-regulated |

| hsa-miR-146a | Unspecified | up-regulated |

| hsa-miR-145 | Causal | down-regulated |

| HMDD (the Human microRNA Disease Database) | |

|---|---|

| miRNA | Description |

| hsa-mir-21 | miR-21:miR-21 might be a novel therapeutic target in cardiovascular diseases |

| hsa-mir-34a | MiR-34a:MicroRNA-34a regulation of endothelial senescence |

| hsa-mir-126 | miR-126, miR-24 and miR-23a are selectively expressed in microvascular endothelial cells in vivo |

| hsa-mir-126 | plasma;Aspirin treatment hampers the use of plasma microRNA-126 as a biomarker for the progression of vascular disease |

| hsa-mir-145 | elevated levels of miR-145 reduced migration of microvascular cells in response to growth factor gradients in vitro |

| hsa-mir-145 | MicroRNA-modulated targeting of vascular smooth muscle cells |

| hsa-mir-17 | miR-17-92 and miR-17-5p/miR-20a; MicroRNA-modulated targeting of vascular smooth muscle cells |

| hsa-mir-18a | miR-17-92 and miR-17-5p/miR-20a; MicroRNA-modulated targeting of vascular smooth muscle cells |

| hsa-mir-19a | miR-17-92 and miR-17-5p/miR-20a; MicroRNA-modulated targeting of vascular smooth muscle cells |

| hsa-mir-20a | miR-17-92 and miR-17-5p/miR-20a; MicroRNA-modulated targeting of vascular smooth muscle cells |

| hsa-mir-21 | miR-21 is found to play important roles in vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and apoptosis, cardiac cell growth and death, and cardiac fibroblast functions |

| hsa-mir-23a | miR-126, miR-24 and miR-23a are selectively expressed in microvascular endothelial cells in vivo |

| hsa-mir-23a | miRNA-23/27/24 cluster has potential therapeutic application in vascular disorders and ischemic heart disease |

| hsa-mir-24-2 | miRNA-23/27/24 cluster has potential therapeutic application in vascular disorders and ischemic heart disease |

| hsa-mir-27a | miRNA-23/27/24 cluster has potential therapeutic application in vascular disorders and ischemic heart disease |

| miRNA | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-mir-21 | hsa-mir-17 | hsa-mir-93 | hsa-mir-10b |

| hsa-mir-452 | hsa-mir-106b | hsa-mir-152 | hsa-mir-125a |

| hsa-mir-365a | hsa-mir-15b | hsa-mir-30d | hsa-miR-133b |

| hsa-mir-140 | hsa-mir-99b | hsa-mir-374a | hsa-mir-20a |

| hsa-mir-146a | hsa-mir-186 | hsa-let-7b | hsa-mir-125b-1 |

| hsa-mir-22 | hsa-mir-133b | hsa-mir-99a | hsa-mir-214 |

| hsa-mir-222 | hsa-mir-193b | hsa-mir-501 | hsa-mir-199a-1 |

| hsa-mir-126 | hsa-mir-342 | hsa-mir-25 | hsa-mir-32 |

| hsa-mir-15a | hsa-mir-148a | hsa-mir-1-2 | hsa-mir-92a-1 |

| hsa-mir-181a-1 | hsa-mir-10a | hsa-miR-451a | hsa-mir-135b |

| hsa-mir-224 | hsa-miR-155-5p | hsa-miR-150-5p | hsa-mir-320a |

| hsa-mir-221 | hsa-mir-196b | hsa-miR-210-3p | hsa-mir-139 |

| hsa-mir-29c | hsa-mir-106a | hsa-mir-642a | hsa-mir-130a |

| hsa-mir-194-2 | hsa-mir-155 | hsa-mir-194-1 | hsa-mir-133a-1 |

| hsa-mir-192 | hsa-miR-1-3p | hsa-let-7c | hsa-mir-375 |

| hsa-mir-193a | hsa-let-7d | hsa-mir-223 | hsa-miR-186-5p |

| hsa-mir-30e | hsa-mir-196a-1 | hsa-mir-650 | hsa-mir-582 |

| hsa-mir-362 | hsa-mir-203a | hsa-mir-195 | hsa-mir-215 |

| hsa-mir-572 | hsa-mir-451a | hsa-mir-197 | hsa-miR-133a-3p |

| hsa-mir-34a | hsa-mir-95 | hsa-mir-16-1 | hsa-mir-486-1 |

| hsa-mir-19a | hsa-miR-146a-5p | hsa-mir-449a | |

| hsa-mir-33a | hsa-mir-181b-1 | hsa-mir-184 | |

| hsa-mir-181a-2 | hsa-mir-19b-1 | hsa-mir-200b |

Table 2.

List of miRNAs associated with vascular diseases whose expression profile was altered when exposed to Aroclor 1260.

| Probe_Set_ID | Transcript ID | p_value | p_value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 20500489 | hsa-miR-224-5p | 0.0201 | 2.26 |

| 20500141 | hsa-miR-21-5p | 0.0283 | 2.07 |

| 20500745 | hsa-miR-140-5p | 0.0458 | 2 |

| 20502451 | hsa-miR-452-5p | 0.0163 | 1.89 |

| 20501182 | hsa-miR-30e-5p | 0.0272 | 1.88 |

| 20500483 | hsa-miR-221-5p | 0.0386 | 1.79 |

| 20500385 | hsa-miR-192-5p | 0.0393 | 1.75 |

| 20500443 | hsa-miR-34a-3p | 0.0398 | 1.6 |

| 20501159 | hsa-miR-29c-5p | 0.04 | 1.53 |

| 20534539 | hsa-mir-222 | 0.036 | 1.31 |

| 20534832 | hsa-mir-362 | 0.0266 | 1.31 |

| 20534633 | hsa-mir-193a | 0.0332 | 1.3 |

| 20500779 | hsa-miR-146a-3p | 0.0224 | 1.26 |

| 20534362 | hsa-mir-22 | 0.0262 | 1.23 |

| 20534617 | hsa-mir-126 | 0.0374 | 1.19 |

| 20534351 | hsa-mir-15a | 0.0332 | 1.18 |

| 20534529 | hsa-mir-181a-1 | 0.0408 | 1.17 |

| 20534837 | hsa-mir-365a | 0.0425 | 0.91 |

| 20504295 | hsa-miR-572 | 0.0112 | 0.84 |

| 20534356 | hsa-mir-19a | 0.0104 | 0.77 |

| 20534809 | hsa-mir-194-2 | 0.0064 | 0.65 |

3.2. Functional role of microRNAs that were altered with Aroclor 1260 exposure

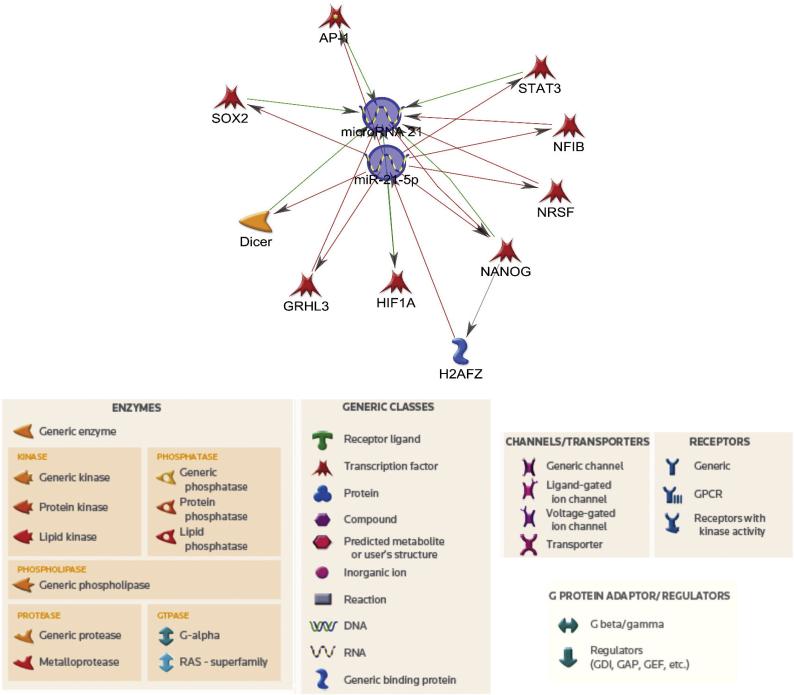

The MetaCore pathway analysis was performed on the 21 miRNAs associated with vascular diseases that were altered with Aroclor 1260 exposure. The in-silico network analyses generate visual representation schemes of biological molecules linking miRNAs with their target mRNAs and identifying miRNA-mRNA pairs. The miRNA-mRNA interactions are represented for miR-21 since it is a widely studied miRNA (Fig. 2) and for other miRNAs as well (Supplementary Figs).

Figure 2.

Network analysis showing pathways linking miR-21 to its suggested target genes. The annotations of symbols in the regulatory network are shown. The arrowheads indicate the direction of the predicted interaction. Red lines represent downregulation and green lines represent upregulation, while gray lines represent an unspecified effect.

The network analysis suggested a direct binding of miR-21-5p to hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1A), leading to its activation whereas there was a direct and negative interaction with other target genes, notably activator protein 1 (AP-1), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and nuclear factor 1 B-type (NF1B) (Fig. 2). There was a negative correlation between miR-146a-3p and TRAF-6 as well as CXCR4 which also appeared complex because TRAF6 and CXCR4 had opposite effects on STAT3 (Supplementary Fig. 1). For the other miRNAs linked to vascular diseases, miR-31 had a direct interaction with SOX4, miR-15a-5p interacted directly with c-Myb and AP-4 and miR-224-5p negatively inhibits SMAD4 and E-cadherin amongst other targets.

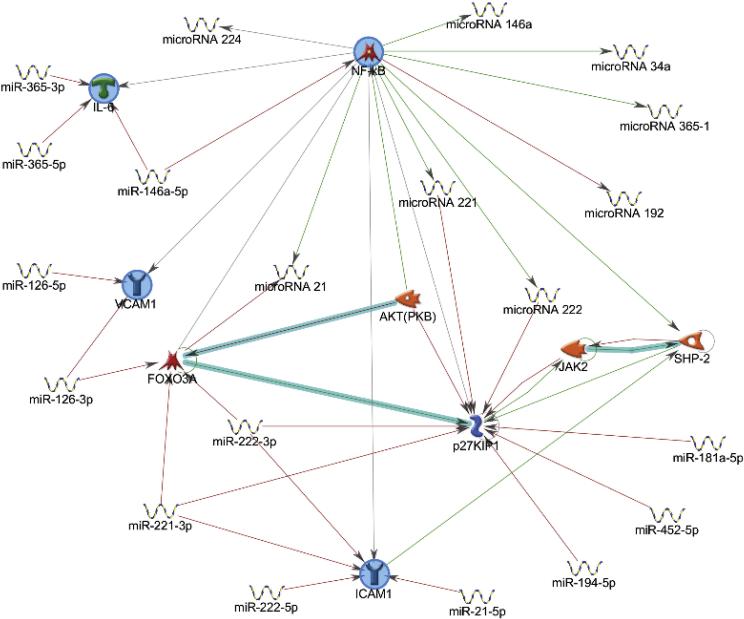

Because this particular network analysis only gave pathways directly linking miRNAs to their targets using Dijkstra's shortest paths algorithm (calculating the shortest directed paths between selected objects), another set of network analysis was ran to identify pathways linking miRNAs and genes that were reported to play a role in PCB-induced vascular endothelial toxicity. This was performed using the auto expand mode in the MetaCore program. This mode draws sub-networks around the selected objects and expansion halts when the sub-networks intersect. The network analysis looking at inflammatory genes, namely NF-ĸB, IL-6, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 suggested a direct correlation between certain miRNAs including miR-21-5p, miR-146a-5p, and miR-222 with these genes (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Network analysis showing interactions between different miRNAs with A. caveolin proteins and p53 and B. pro-inflammatory cytokines.

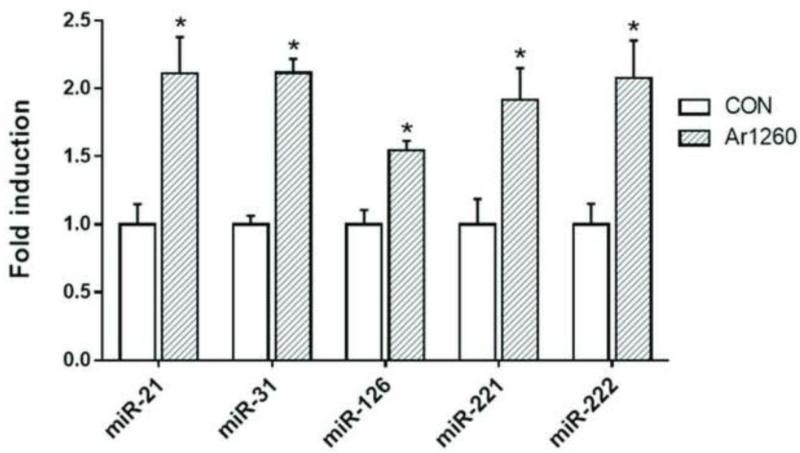

3.3. Validation of selected microRNA expression in HUVECs

To validate the microarray findings, the effects of Aroclor 1260 exposure on miRNA gene expression was tested using HUVECs. Primary endothelial cells were exposed to Aroclor 1260 at 10 μM and gene expression was measured by real time-PCR. Consistent with the microarray results, the mRNA expression of miRNAs namely miR-21, miR-31, miR-126, miR-221 and miR-222 were significantly induced with Aroclor 1260 exposure in the primary human endothelial cells (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Exposure to the PCB mixture Aroclor 1260 increased the gene expression of selected miRNAs in HUVEC cells. Gene expression was measured using real time-PCR. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. (*) denotes statistical significance, p <0.05.

4. Discussion

The role of environmental pollutants such as PCBs on epigenetic regulation has been investigated only recently (Casati et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015; Ovesen et al., 2011). Clearly there is concrete evidence that environmental chemicals have the ability to alter certain chemical processes and interactions related to DNA methylation, histone modifications, and miRNA regulation, among others that consequently affect gene transcription, translation and protein turnover. Moreover, with the emerging concept of the ‘exposome’, which relates to all types of environmental exposures in a human's life course, it has become increasingly important to identify the mechanistic actions of environmental chemicals and how these environmental exposures can influence health outcomes. In this particular study, a component of the gene regulation pathway pertaining to miRNA expression profiles is addressed. Because miRNAs have been proposed as biomarkers for diseased states (Wang et al., 2016), they can also potentially be used as biomarkers for PCB exposure and PCB-induced diseases. Environmental exposure to PCBs have been positively correlated to various diseases directed to either a particular or multiple organ systems such as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatosis, diabetes and insulin resistance, obesity, and hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke (Bergkvist et al., 2015; Bergkvist et al., 2014; Cave et al., 2010; Donat-Vargas et al., 2015). Furthermore, a number of diagnostic markers have been proposed for PCB exposure such as elevated serum liver enzymes and elevated cholesterol and triglycerides which are risk factors for either liver diseases or cardiovascular diseases.

The PCB congeners most commonly associated with cardiovascular complications, predominantly hypertension, are the mono-ortho chlorinated PCBs, coplanar congeners and dioxin-like PCBs (PCBs 74, 101, 118, 126 and 138) and to a certain degree, non-coplanar PCBs (PCB 153 and 180) (Goncharov et al., 2011; Peters et al., 2014; Van Larebeke et al., 2015). In the current study, a commercial PCB mixture, Aroclor 1260 was used whose composition represents highly chlorinated, non-metabolizable PCBs. Because the PCB congeners that bioaccumulate in humans and are responsible for the effects of chronic exposure are the non-metabolizable ones, the study therefore focused on human exposure paradigms. Moreover, the congener composition in Aroclor 1260 resembles that of human adipose tissue (Wahlang et al., 2014) which consists of mostly non-coplanar, highly chlorinated congeners. The findings of the current study indicated that PCB exposure changes the miRNA profile in human endothelial cells. These miRNAs were then filtered and only those reported to be involved in vascular diseases were chosen for further evaluation. Based on preliminary studies and information obtained from available databases, 21 miRNAs were then shortlisted and some of them, namely miR-21, miR-31, miR-126, miR-221 and miR-222, were further validated. The expression levels of these randomly selected miRNAs were assessed using real time PCR and the results confirmed the microarray data findings. Importantly, these miRNAs have been reported to influence vascular inflammation and atherosclerotic vascular disease (Ono et al., 2011).

The role of miR-21 in CVD is controversial with some studies reporting induction of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by miR-21 while others reporting its anti-hypertrophic activity (Cheng et al., 2007; Tatsuguchi et al., 2007). Nevertheless, miR-21expression is upregulated in cardiac injury and has become an increasingly relevant miRNA marker for CVD. Additionally, miR-21 also functions as an oncogene by inhibiting apoptosis and its upregulation promotes proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (Kang et al., 2012). It has also been reported that miR-21 negatively regulates PPARα and VCAM-1 expression (Chamorro-Jorganes et al., 2013). In this study, Aroclor 1260 exposure at 10 μM induced miR-21-5p expression in HUVECs. Further in-silico analysis suggested that miR-21-5p can directly activate HIF1A, a subunit of the heterodimeric transcription factor hypoxia-inducible factor 1 that regulates cellular response to hypoxia. HIF1A over expression has been linked to vascularization and angiogenesis (Wang et al., 1995). Additionally, the in-silico analysis suggested that miR-21 can directly inhibit AP-1 and STAT3 transcription, and both proteins are transcription factors for genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis. Interestingly a recent study demonstrated that AP-1, whose expression is induced by cytokines and growth factors, is a transcriptional activator for miR-21 (Lorenzen et al., 2015). Moreover, the study reported a significant increase in miR-21 in patients with myocardial fibrosis. This implicates that PCB exposure may have induced vascular cell injury leading to cytokine induction and consequently upregulating miR-21. Exposure to metal-rich particulate matter has also been reported to upregulate miR-21 which was also implicated in the etiology of atherosclerosis (Raitoharju et al., 2011; Vrijens et al., 2015).

Other in-silico findings suggested that the selected miRNAs can interact with proteins involved in the inflammatory response and cell proliferation such as TRAF-6 and CXCR4 (miR-146a-3p), AP-4 (miR-15a-5p) and SMAD4 and E-cadherin (miR-224-5p). For example, TRAF6 mediates signal transduction in the NF-ĸB pathway in response to pro-inflammatory cytokines (Qian et al., 2001). Other miRNAs that were induced by exposure to Aroclor 1260, such as miR-31, can interact with target genes including SOX4 that are required for B-lymphocyte development (Smith and Sigvardsson, 2004). Also, miR-31 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine (TNFα)-induced miRNA that regulates E-selectin and ICAM-1 expression and is implicated in the negative feedback loop that controls inflammation (Suarez et al., 2010). On the other hand, the in-silico findings suggested that miR-126 can inhibit VCAM-1 expression, thereby modulating leukocyte trafficking in the endothelium and vascular inflammation (Harris et al., 2008).

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the miRNA expression profile with regards to PCB exposure in human endothelial cells. However, another study did report alterations in miRNA expression profile in differentiating mouse cardiomyocytes exposed to the PCB mixture, Aroclor 1254 (Zhu et al., 2012). In conclusion, in the current study we evaluated the miRNA expression profile associated with PCB exposure to human endothelial cells. PCB exposure clearly upregulate a number of miRNAs associated with inflammation and CVDs. The study suggest that miRNA regulation may be another potential mechanisms of PCB action. Furthermore, these changes in miRNA levels could be an applicable approach for disease prognosis and diagnosis in PCB-exposed human cohorts. These data provide some insight and direction toward understanding some of the unanswered questions related to toxicant mechanism of action and implicates the relevance of miRNAs as potential biomarkers for environmental toxicant-induced diseases.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The PCB mixture, Aroclor 1260 induced changes in microRNA expression profile in human umbilical vein endothelial cells

Microarray analysis identified 557 out of 6658 microRNAs that were changed with PCB exposure

In-silico analysis using MetaCore database identified 21 of these microRNAs to be associated with vascular diseases

Further validation showed increased miR-21, miR-31, miR-126, miR-221 and miR-222 expression levels with PCB exposure

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Kuey-Chu Chen and Donna Wall of the UK Microarray Core and the University of Louisville for assistance in the microarray experiments and MetaCore software respectively.

Funding statement

This work is supported by the NIH/NIEHS grant P42ES007380 and the NIGMS/NIH grant 5P20GM103436-15.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article

References

- Ardekani AM, Naeini MM. The Role of MicroRNAs in Human Diseases. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol. 2010;2(4):161–179. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arzuaga X, Reiterer G, Majkova Z, Kilgore MW, Toborek M, Hennig B. PPARalpha ligands reduce PCB-induced endothelial activation: possible interactions in inflammation and atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2007;7(4):264–272. doi: 10.1007/s12012-007-9005-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergkvist C, Berglund M, Glynn A, Wolk A, Akesson A. Dietary exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls and risk of myocardial infarction - a population-based prospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol. 2015:183242–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergkvist C, Kippler M, Larsson SC, Berglund M, Glynn A, Wolk A, Akesson A. Dietary exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls is associated with increased risk of stroke in women. J Intern Med. 2014;276(3):248–259. doi: 10.1111/joim.12194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casati L, Sendra R, Poletti A, Negri-Cesi P, Celotti F. Androgen receptor activation by polychlorinated biphenyls: epigenetic effects mediated by the histone demethylase Jarid1b. Epigenetics. 2013;8(10):1061–1068. doi: 10.4161/epi.25811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cave M, Appana S, Patel M, Falkner KC, McClain CJ, Brock G. Polychlorinated biphenyls, lead, and mercury are associated with liver disease in American adults: NHANES 2003-2004. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(12):1735–1742. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro-Jorganes A, Araldi E, Suarez Y. MicroRNAs as pharmacological targets in endothelial cell function and dysfunction. Pharmacol Res. 2013:7515–27. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Lui TN, Lin JW, Lin YL, Hsing CH, Wang JJ, Chen RM. Roles of microRNA-1 in hypoxia-induced apoptotic insults to neuronal cells. Arch Toxicol. 2016;90(1):191–202. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1364-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y, Ji R, Yue J, Yang J, Liu X, Chen H, Dean DB, Zhang C. MicroRNAs are aberrantly expressed in hypertrophic heart: do they play a role in cardiac hypertrophy? Am J Pathol. 2007;170(6):1831–1840. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.061170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donat-Vargas C, Gea A, Sayon-Orea C, de la Fuente-Arrillaga C, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Association between dietary intake of polychlorinated biphenyls and the incidence of hypertension in a Spanish cohort: the Seguimiento Universidad de Navarra project. Hypertension. 2015;65(4):714–721. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong Van Huyen JP, Tible M, Gay A, Guillemain R, Aubert O, Varnous S, Iserin F, Rouvier P, Francois A, Vernerey D, Loyer X, Leprince P, Empana JP, Bruneval P, Loupy A, Jouven X. MicroRNAs as non-invasive biomarkers of heart transplant rejection. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(45):3194–3202. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehu346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Hernando C, Baldan A. MicroRNAs and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2013;1(1):30–38. doi: 10.1007/s40142-013-0008-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncharov A, Pavuk M, Foushee HR, Carpenter DO. Blood pressure in relation to concentrations of PCB congeners and chlorinated pesticides. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119(3):319–325. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris TA, Yamakuchi M, Ferlito M, Mendell JT, Lowenstein CJ. MicroRNA-126 regulates endothelial expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1516–1521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707493105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang H, Davis-Dusenbery BN, Nguyen PH, Lal A, Lieberman J, Van Aelst L, Lagna G, Hata A. Bone morphogenetic protein 4 promotes vascular smooth muscle contractility by activating microRNA-21 (miR-21), which down-regulates expression of family of dedicator of cytokinesis (DOCK) proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(6):3976–3986. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.303156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KM, Kim SG. Autophagy and microRNA dysregulation in liver diseases. Arch Pharm Res. 2014;37(9):1097–1116. doi: 10.1007/s12272-014-0439-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Kowdley KV. MicroRNAs in common human diseases. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2012;10(5):246–253. doi: 10.1016/j.gpb.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Perkins JT, Petriello MC, Hennig B. Exposure to coplanar PCBs induces endothelial cell inflammation through epigenetic regulation of NF-kappaB subunit p65. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2015;289(3):457–465. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzen JM, Schauerte C, Hubner A, Kolling M, Martino F, Scherf K, Batkai S, Zimmer K, Foinquinos A, Kaucsar T, Fiedler J, Kumarswamy R, Bang C, Hartmann D, Gupta SK, Kielstein J, Jungmann A, Katus HA, Weidemann F, Muller OJ, Haller H, Thum T. Osteopontin is indispensible for AP1-mediated angiotensin II-related miR-21 transcription during cardiac fibrosis. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(32):2184–2196. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthe G, Jacobus JA, Robertson LW. Receptor interactions by polybrominated diphenyl ethers versus polychlorinated biphenyls: a theoretical Structure-activity assessment. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2008;25(2):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2007.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Kuwabara Y, Han J. MicroRNAs and cardiovascular diseases. FEBS J. 2011;278(10):1619–1633. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08090.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ovesen JL, Schnekenburger M, Puga A. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligands of widely different toxic equivalency factors induce similar histone marks in target gene chromatin. Toxicol Sci. 2011;121(1):123–131. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfr032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagidipati NJ, Gaziano TA. Estimating deaths from cardiovascular disease: a review of global methodologies of mortality measurement. Circulation. 2013;127(6):749–756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.128413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins JT, Petriello MC, Newsome BJ, Hennig B. Polychlorinated biphenyls and links to cardiovascular disease. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23(3):2160–2172. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-4479-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JL, Fabian MP, Levy JI. Combined impact of lead, cadmium, polychlorinated biphenyls and non-chemical risk factors on blood pressure in NHANES. Environ Res. 2014:13293–99. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2014.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petriello MC, Han SG, Newsome BJ, Hennig B. PCB 126 toxicity is modulated by cross-talk between caveolae and Nrf2 signaling. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2014;277(2):192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichler M, Calin GA. MicroRNAs in cancer: from developmental genes in worms to their clinical application in patients. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(4):569–573. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirola CJ, Fernandez Gianotti T, Castano GO, Mallardi P, San Martino J, Mora Gonzalez Lopez Ledesma M, Flichman D, Mirshahi F, Sanyal AJ, Sookoian S. Circulating microRNA signature in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: from serum non-coding RNAs to liver histology and disease pathogenesis. Gut. 2015;64(5):800–812. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, Noonan EJ, Dahiya R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(5):1608–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707594105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Y, Commane M, Ninomiya-Tsuji J, Matsumoto K, Li X. IRAK-mediated translocation of TRAF6 and TAB2 in the interleukin-1-induced activation of NFkappa B. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(45):41661–41667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raitoharju E, Lyytikainen LP, Levula M, Oksala N, Mennander A, Tarkka M, Klopp N, Illig T, Kahonen M, Karhunen PJ, Laaksonen R, Lehtimaki T. miR-21, miR-210, miR-34a, and miR-146a/b are up-regulated in human atherosclerotic plaques in the Tampere Vascular Study. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219(1):211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small EM, Frost RJ, Olson EN. MicroRNAs add a new dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1022–1032. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.889048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith E, Sigvardsson M. The roles of transcription factors in B lymphocyte commitment, development, and transformation. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75(6):973–981. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Selvan ST, Archunan G, Gulyas B, Padmanabhan P. MicroRNAs -the next generation therapeutic targets in human diseases. Theranostics. 2013;3(12):930–942. doi: 10.7150/thno.7026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez Y, Wang C, Manes TD, Pober JS. Cutting edge: TNF-induced microRNAs regulate TNF-induced expression of E-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 on human endothelial cells: feedback control of inflammation. J Immunol. 2010;184(1):21–25. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsuguchi M, Seok HY, Callis TE, Thomson JM, Chen JF, Newman M, Rojas M, Hammond SM, Wang DZ. Expression of microRNAs is dynamically regulated during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42(6):1137–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Larebeke N, Sioen I, Hond ED, Nelen V, Van de Mieroop E, Nawrot T, Bruckers L, Schoeters G, Baeyens W. Internal exposure to organochlorine pollutants and cadmium and self-reported health status: a prospective study. Int J Hyg Environ Health. 2015;218(2):232–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2014.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrijens K, Bollati V, Nawrot TS. MicroRNAs as potential signatures of environmental exposure or effect: a systematic review. Environ Health Perspect. 2015;123(5):399–411. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1408459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahlang B, Falkner KC, Clair HB, Al-Eryani L, Prough RA, States JC, Coslo DM, Omiecinski CJ, Cave MC. Human receptor activation by aroclor 1260, a polychlorinated biphenyl mixture. Toxicol Sci. 2014;140(2):283–297. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfu083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Jiang BH, Rue EA, Semenza GL. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 is a basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS heterodimer regulated by cellular O2 tension. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(12):5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Chen J, Sen S. MicroRNA as Biomarkers and Diagnostics. J Cell Physiol. 2016;231(1):25–30. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, Yu ZB, Zhu JG, Hu XS, Chen YL, Qiu YF, Xu ZF, Qian LM, Han SP. Differential expression profile of MicroRNAs during differentiation of cardiomyocytes exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(12):15955–15966. doi: 10.3390/ijms131215955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.