Summary

Our goal was to describe prevalence of β-HPVs at three anatomic sites among 717 men from Brazil, Mexico and US enrolled in the HPV Infection in Men (HIM) Study. β-HPVs were genotyped using Luminex technology. Overall, 77.7%, 54.3% and 29.3% men were positive for any β-HPV at the genitals, anal canal, and oral cavity, respectively. Men from US and Brazil were significantly less likely to have β-HPV at the anal canal than men from Mexico. Older men were more likely to have β-HPV at the anal canal compared to younger men. Prevalence of β-HPV at the oral cavity was significantly associated with country of origin and age. Current smokers were significantly less likely to have β-HPV in the oral cavity than men who never smoked. Lack of associations between β-HPV and sexual behaviors may suggest other routes of contact such as autoinoculation which need to be explored further.

Keywords: cutaneous human papillomavirus, males, HIM Study, prevalence, anogenital, oral

Introduction

Most human papillomaviruses (HPV) encompass three genera: alpha papillomavirus (α-HPV), which are primarily isolated from mucosal and genital lesions, and beta and gamma papillomavirus (β- and γ-HPV), which have mostly been detected on the skin. β- and γ-HPV together comprise >100 viral types ubiquitously distributed throughout the body since early infancy, suggesting these may be part of the commensal flora 1,2. Next-generation sequencing further points towards the existence of hundreds of putative novel cutaneous HPV types 3,4. β-HPV 5 and 8 are recognized etiological agents of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) among epidermodysplasia verruciformis patients primarily in sun-exposed skin 5. In addition, some studies provide data suggesting a possible role of certain β-HPVs in early stages of skin carcinogenesis among immunocompetent individuals 6–11. Nevertheless, further research is needed to better understand the widespread distribution of these viruses, and the potential association with SCC development 8,12,13.

We and others have recently described the high prevalence and diversity of β-HPVs at non-cutaneous anatomic sites 14–19. The purpose of this study was to describe the prevalence of 43 β-HPV types among samples collected at the same time point from the external genital skin, the anal canal, and oral cavity from men enrolled in the multinational HPV Infection in Men (HIM) cohort study.

Materials and Methods

Clinical samples

Over 4,000 HIM Study participants were enrolled in São Paulo, Brazil; Cuernavaca, Mexico; and Tampa, US between 2005 and 2009, and followed every six months for a median of four years. Inclusion criteria were age 18–70 years at enrollment, no prior anogenital cancer or warts (Note: no exclusion was based on head and neck cancer), and no current sexually transmitted disease (STD) diagnosis, including HIV. No exclusion was made for head and neck cancer. Detailed study methods are described elsewhere 20–22. The study was approved by Human Subjects Committees at each study site. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to enrollment.

Men completed a self-administered computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) questionnaire gathering information about participant demographic characteristics, substance use, and sexual behaviors 20,21. During the clinical examination, three different prewetted Dacron applicators were used to sample the external genitalia and scrotum of participants, and were later combined to form a single sample 20. Using a separate swab, exfoliated cells were collected from between the anal verge and the dentate line 21. Oral gargle specimens were collected via mouthwash and processed as described 22. For the present study, we selected the first 243 men enrolled in each country who had provided specimens from all three anatomic sites (genitals, anal canal, and oral cavity) at the same study visit.

β-HPV detection and characterization

Specimens were digested with proteinase K-SDS 1% and HPV DNA was obtained by organic extraction 23. HPV DNA was measured in all samples using type-specific PCR bead-based multiplex genotyping (TS-MPG) assays that combine multiplex polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and bead-based Luminex technology (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX, USA), as described elsewhere 18,24–29. A mixture of specific biotinylated primers was used to amplify simultaneously ~250 bp of the E7 gene of 43 β-HPV from five different species 25. Two primers for β-globin amplification were included to evaluate the quality of template DNA 30. Multiplex PCRs were performed with the QIAGEN multiplex PCR kit according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany). Following PCR amplification, 10μL of each reaction mixture was analyzed by a bead-based multiplex HPV genotyping protocol 24 in a Luminex 200 reader (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). The results are expressed as the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of at least 100 beads per bead set. For each probe, the MFI values obtained when no PCR product was added to the hybridization mixture were considered the background values. Cutoffs were computed by adding 20 MFI to 1.1X the median background values.

Statistical analysis

Questionnaire data for each participant were obtained from the same visit that the genital, anal canal and oral specimens were acquired. We compared demographic and sexual characteristics between men that were positive for any of the β-HPV types to men that were negative for all of the β-HPV types at each anatomic site using Pearson Chi-square tests. Multiple infections were defined as the presence of >1 β-HPV type at the same anatomic site. Sexual orientation was categorized based on self-reported recent (previous 3–6 months) and lifetime sexual behavior (vaginal, anal, and oral sex). Men were defined as “virgins” when they reported no female or male sexual partners ever.

Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using logistic regression to assess factors associated with any β-HPV detection at each anatomic site. Backwards elimination was used to determine factors independently associated with any β-HPV detection at each anatomic site with p value ≤ 0.20 chosen as the a priori cutoff for retention in the multivariable model. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

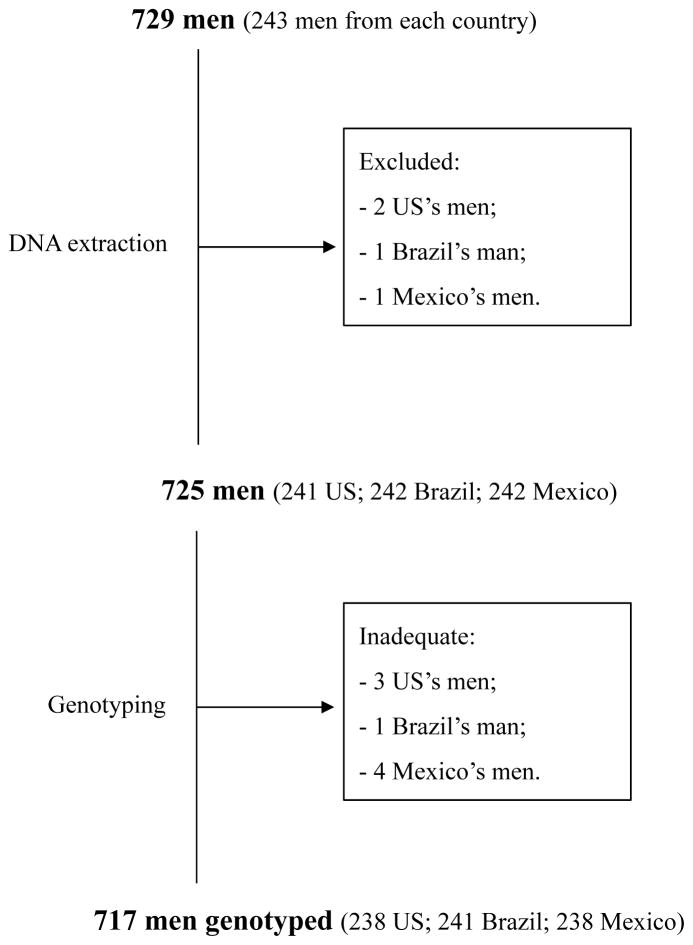

β-globin amplification was successful for 697 (97.2%), 713 (99.4%) and 717 (100%) samples from the genital, anal canal, and oral regions, respectively. Twelve men were excluded from the analysis: eight men had at least one inadequate specimen (β-globin negative/HPV negative) and for four men DNA isolation failed in one of the samples. Thus, the current analysis included 717 men (238 US, 241 Brazil and 238 Mexico) for whom results were considered adequate for all three anatomic sites (β-globin positive/β-HPV negative or β-globin negative/β-HPV positive) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study design indicating number of participants in the HPV Infection in Men Study analyzed by anatomic site (external genital skin, anal canal and oral cavity) and country (US, Mexico and Brazil).

Overall, the majority of the study population (n=717) was less than 44 years old (87%), white (52%), non-Hispanic (56%), not circumcised (63%), married or cohabiting (51%), and never smoked (60%). A large proportion of these men reported having sex with women (85%) and the majority reported nine or less sexual partners (55%) (data not shown).

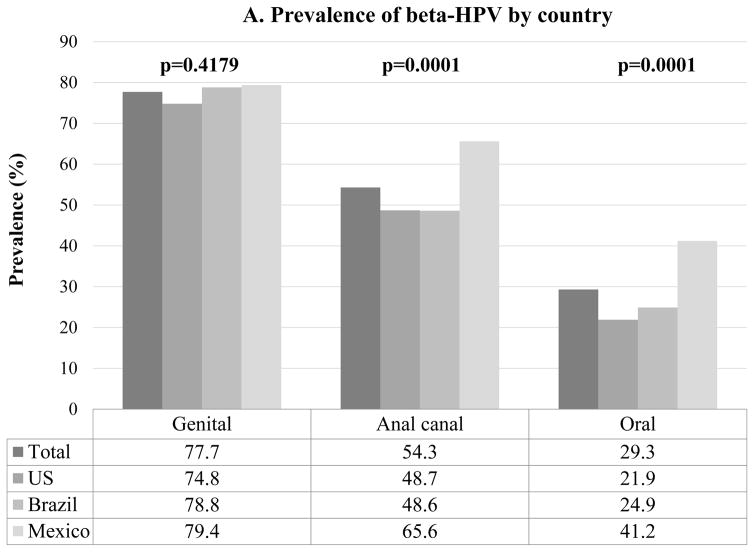

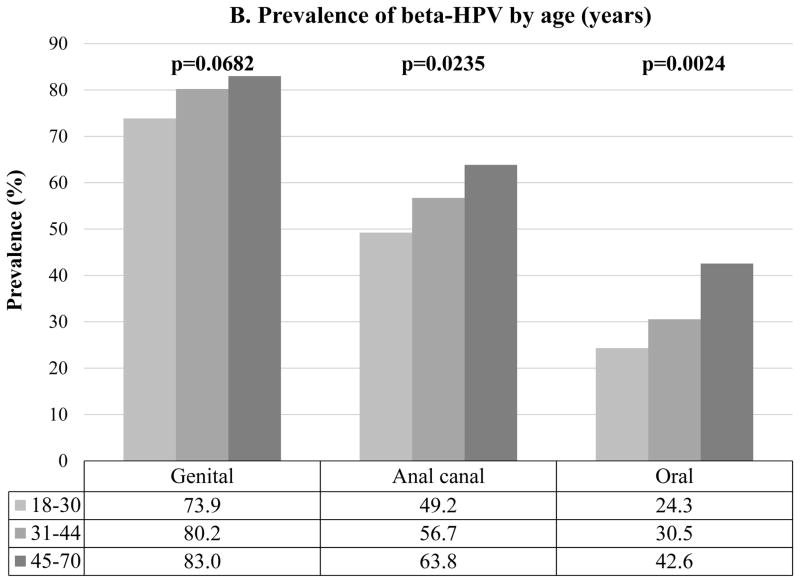

At least one β-HPV type was detected at any one of the three anatomic sites in 637 (89%) men. Any β-HPV was detected among 557 (77.7%) men at the genital, 389 (54.3%) at the anal canal and 210 (29.3%) at the oral cavity (Figure 2A). Men in Mexico had significantly higher prevalence of β-HPV at the anal canal (p=0.0001) and oral cavity (p=0.0001) compared to both men from the US and Brazil (Figure 2A). At the anal canal and oral cavity, β-HPV prevalence significantly increased with increasing age (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Overall β-HPV (Human papillomavirus) prevalence by (A) country and (B) age at the genital, anal canal and oral cavity of men participating in the HIM study (n=717). p value (p) were calculated by the Chi-square test.

A total of 3,302 single β-HPV infections across all anatomic sites were detected among the 717 men. Major β-HPV species detected were β-1 (1281/3302, 38.8%) and β-2 (1682/3302, 50.9%) regardless of the anatomic site. The most prevalent viral types at all three anatomic sites were HPV-21 and HPV-24 (β-1), and HPV-22 and HPV-38 (β-2) (Table 1). HPV-150 was the only type not detected in any of the samples tested. Multiple β-HPV types were more likely to be detected at the genital (ranged from 2–19 types detected) than at the anal canal (2–9) or oral cavity (2–11) (Table 1).

Table 1.

β-HPV (Human papillomavirus) type distribution at the genital, anal canal and oral cavity collected at the same visit of 717 men participating in the HPV Infection in Men Study.

| Species | Type | Genital n(%) |

Anal canal n(%) |

Oral cavity n(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B1 | HPV-5 | 70 (9.8) | 34 (4.7) | 11 (1.5) |

| HPV-8 | 86 (12.0) | 45 (6.3) | 20 (2.8) | |

| HPV-12 | 77 (10.7) | 25 (3.5) | 14 (2.0) | |

| HPV-14 | 36 (5.0) | 10 (1.4) | 3 (4.0) | |

| HPV-19 | 15 (2.1) | 7 (1.0) | 4 (0.6) | |

| HPV-20 | 16 (2.2) | 6 (0.8) | 1 (0.1) | |

| HPV-21 | 128 (17.9) | 79 (11.0) | 56 (7.8) | |

| HPV-24 | 110 (15.3) | 53 (7.4) | 30 (4.2) | |

| HPV-25 | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | |

| HPV-36 | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.4) | 5 (0.7) | |

| HPV-47 | 49 (6.8) | 15 (2.1) | 11 (1.5) | |

| HPV-93 | 10 (1.4) | 7 (1.0) | 8 (1.1) | |

| HPV-98 | 29 (4.0) | 17 (2.4) | 8 (1.1) | |

| HPV-99 | 10 (1.4) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HPV-105 | 46 (6.4) | 19 (2.6) | 2 (0.3) | |

| HPV-118 | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HPV-124 | 72 (10.0) | 17 (2.4) | 2 (0.3) | |

| HPV-143 | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||

| B2 | HPV-9 | 46 (6.4) | 15 (2.1) | 5 (0.7) |

| HPV-15 | 27 (3.8) | 7 (1.0) | 7 (1.0) | |

| HPV-17 | 57 (7.9) | 14 (2.0) | 9 (1.3) | |

| HPV-22 | 127 (17.7) | 62 (8.6) | 21 (2.9) | |

| HPV-23 | 87 (12.1) | 26 (3.6) | 2 (0.3) | |

| HPV-37 | 19 (2.6) | 7 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HPV-38 | 198 (27.6) | 87 (12.1) | 45 (6.3) | |

| HPV-80 | 17 (2.4) | 10 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HPV-100 | 54 (7.5) | 19 (2.6) | 15 (2.1) | |

| HPV-104 | 13 (1.8) | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HPV-107 | 79 (11.0) | 30 (4.2) | 4 (0.6) | |

| HPV-110 | 86 (12.0) | 34 (4.7) | 17 (2.4) | |

| HPV-111 | 97 (13.5) | 44 (6.1) | 19 (2.6) | |

| HPV-113 | 32 (4.5) | 9 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| HPV-120 | 63 (8.8) | 23 (3.2) | 2 (0.3) | |

| HPV-122 | 54 (7.5) | 16 (2.2) | 4 (0.6) | |

| HPV-145 | 18 (2.5) | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | |

| HPV-151 | 35 (4.9) | 9 (1.3) | 3 (0.4) | |

|

| ||||

| B3 | HPV-49 | 57 (7.9) | 25 (3.5) | 8 (1.1) |

| HPV-75 | 24 (3.3) | 8 (1.1) | 2 (0.3) | |

| HPV-76 | 94 (13.1) | 43 (6.0) | 19 (2.6) | |

| HPV-115 | 22 (3.1) | 13 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||

| B4 | HPV-92 | 8 (1.1) | 5 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

|

| ||||

| B5 | HPV-96 | 6 (0.8) | 5 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| HPV-150 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

|

| ||||

| Multiple Infection* | 2 types | 109 (15.2) | 89 (12.4) | 46 (6.4) |

| 3 types | 80 (11.2) | 52 (7.3) | 17 (2.4) | |

| 4 types | 65 (9.1) | 23 (3.2) | 7 (1.0) | |

| 5 types | 49 (6.8) | 15 (2.1) | 5 (0.7) | |

| 6 types | 32 (4.5) | 15 (2.1) | 1 (0.1) | |

| ≥7 types | 83 (11.6) | 11 (1.5) | 3 (0.4) | |

- number of men within each category; frequencies refers to n/total number of men (717)

In multivariable logistic regression analyses, age, sexual orientation, and number of alcoholic drinks per month were retained in the final model as explanatory variables for detection of β-HPV at the external genital skin. However, none of these factors reached statistical significance in either unadjusted or multivariable analyses (Table 2). Although not statistically significant, trends were observed for higher prevalence and risk of at least one β-HPV type at the genitals with increasing age (Figure 2B; Table 2) and MSM sexual orientation (Table 2). In addition, men that reported any alcohol intake tended to present lower risk of at least one β-HPV type at the genitals compared to men that never drank alcohol.

Table 2.

Demographic and sexual characteristics associated with at least one β-HPV type DNA detected at the genital in 717 men participating in the HPV Infection in Men Study.

| Characteristics | Genital (N=717) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Negative (N=160) | Positive (N=557) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | |

| Country of residence | ||||

| US | 60 (37.5) | 178 (32.0) | 0.77 (0.50–1.18) | - |

| Brazil | 51 (31.9) | 190 (34.1) | 0.97 (0.62–1.50) | - |

| Mexico | 49 (30.6) | 189 (33.9) | Ref. | - |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–30 | 85 (53.1) | 240 (43.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 31–44 | 59 (36.9) | 239 (42.9) | 0.96 (0.66–1.38) | 1.45 (0.98–2.15) |

| 45–70 | 16 (10.0) | 78 (14.0) | 1.73 (0.96–3.12) | 1.82 (0.98–3.36) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 88 (55.0) | 282 (50.6) | Ref. | - |

| Black or African American | 24 (15.0) | 70 (12.6) | 0.91 (0.54–1.53) | - |

| Asian/pacific islander | 2 (1.3) | 10 (1.8) | 1.56 (0.34–7.26) | - |

| Other/mixed race | 42 (26.3) | 169 (30.3) | 1.26 (0.83–1.90) | - |

| Refused | 4 (2.5) | 26 (4.7) | 2.03 (0.69–5.97) | - |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 63 (39.6) | 248 (44.8) | Ref. | - |

| Non-Hispanic | 96 (60.4) | 306 (55.2) | 0.81 (0.57–1.16) | - |

| Education (years) | ||||

| ≤12 | 64 (40.5) | 248 (44.8) | Ref. | - |

| 13–15 | 49 (31.0) | 148 (26.7) | 0.78 (0.51–1.19) | - |

| ≥16 | 45 (28.5) | 158 (28.5) | 0.91 (0.59–1.39) | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 77 (48.4) | 209 (37.7) | Ref. | - |

| Married/Cohabiting | 66 (41.5) | 296 (53.3) | 1.65 (1.14–2.40) | - |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 16 (10.1) | 50 (9.0) | 1.15 (0.62–2.14) | - |

| Circumcision | ||||

| Not Circumcised | 100 (62.5) | 354 (63.6) | Ref. | - |

| Circumcised | 60 (37.5) | 203 (36.5) | 0.96 (0.66–1.38) | - |

| Lifetime number of female sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 29 (18.1) | 69 (12.6) | Ref. | - |

| 1 | 11 (6.9) | 49 (8.9) | 1.87 (0.85–4.10) | - |

| 2–9 | 60 (37.5) | 215 (39.1) | 1.51 (0.90–2.53) | - |

| 10–49 | 47 (29.4) | 193 (35.1) | 1.73 (1.01–2.96) | - |

| +50 | 13 (8.1) | 24 (4.4) | 0.78 (0.35–1.73) | - |

| Lifetime number of male anal sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 135 (87.7) | 466 (85.7) | Ref. | - |

| 1–9 | 15 (9.7) | 48 (8.8) | 0.93 (0.50–1.71) | - |

| +10 | 4 (2.6) | 30 (5.5) | 2.17 (0.75–6.28) | - |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| MSW | 111 (70.3) | 413 (75.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| MSM | 3 (1.9) | 16 (2.9) | 1.43 (0.41–5.01) | 1.43 (0.40–5.06) |

| MSWM | 20 (12.7) | 68 (12.4) | 0.91 (0.53–1.57) | 1.02 (0.58–1.80) |

| Virgins | 24 (15.2) | 53 (9.6) | 0.59 (0.35–1.00) | 0.60 (0.34–1.04) |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Current | 33 (20.6) | 109 (19.6) | 0.96 (0.66–1.38) | - |

| Former | 34 (21.3) | 112 (20.1) | 0.91 (0.59–1.43) | - |

| Never | 93 (58.1) | 335 (60.3) | Ref. | - |

| Alcoholic drinks (per month) | ||||

| 0 | 31 (20.1) | 144 (26.5) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 1–30 | 121 (78.6) | 393 (72.4) | 0.70 (0.45–1.08) | 0.68 (0.43–1.07) |

| >30 | 2 (1.3) | 6 (1.1) | 0.65 (0.12–3.35) | 0.70 (0.13–3.70) |

Ref. – Reference value (1.00). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using logistic regression to assess factors associated with any β-HPV detection. Backwards elimination was used to determine factors independently associated with any β-HPV detection at each anatomic site with p value ≤ 0.20 chosen as the priori cutoff for retention in the multivariable model.

Approximately half of the study population (54.3%) had at least one β-HPV type detected at the anal canal. Men from Brazil (adjusted OR(aOR)=0.49, 95% CI 0.33–0.73) and the US (aOR=0.55, 95% CI 0.38–0.80) were significantly less likely to have a β-HPV type detected at the anal canal compared to men from Mexico (Figure 2A, Table 3) after adjusting for age. Older age (aOR=1.59, 95% CI 0.98–2.58) was marginally associated with increased detection of at least one β-HPV type at the anal canal compared to younger aged men after adjusting for country. In models that also included lifetime number of male anal sex partners there was no change in the odds ratios for the association with country or age (data not shown).

Table 3.

Demographic and sexual characteristics associated with at least one β-HPV type DNA detected in the anal canal in 717 men participating in the HPV Infection in Men Study.

| Characteristics | Anal canal (N=717) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Negative (N=328) | Positive (N=389) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | |

| Country of residence | ||||

| US | 122 (37.2) | 116 (29.8) | 0.50 (0.35–0.72) | 0.55 (0.38–0.80) |

| Brazil | 124 (37.8) | 117 (30.1) | 0.50 (0.34–0.72) | 0.49 (0.33–0.73) |

| Mexico | 82 (25.0) | 156 (40.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–30 | 165 (50.3) | 160 (41.1) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 31–44 | 129 (39.3) | 169 (43.4) | 1.35 (0.99–1.85) | 1.30 (0.93–1.82) |

| 45–70 | 34 (10.4) | 60 (15.4) | 1.82 (1.13–2.92) | 1.59 (0.98–2.58) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 185 (56.4) | 185 (47.6) | Ref. | - |

| Black or African American | 53 (16.2) | 41 (10.5) | 0.77 (0.49–1.22) | - |

| Asian/pacific islander | 3 (0.9) | 9 (2.3) | 3.00 (0.80–11.26) | - |

| Other/mixed race | 75 (22.9) | 136 (35.0) | 1.81 (1.28–2.57) | - |

| Refused | 12 (3.7) | 18 (4.6) | 1.50 (0.70–3.20) | - |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 119 (36.5) | 192 (49.6) | Ref. | - |

| Non-Hispanic | 207 (63.5) | 195 (50.4) | 0.58 (0.43–0.79) | - |

| Education (years) | ||||

| ≤12 | 123 (38) | 189 (48.7) | Ref. | - |

| 13–15 | 100 (30.9) | 97 (25.0) | 0.63 (0.44–0.91) | - |

| ≥16 | 101 (31.2) | 102 (26.3) | 0.66 (0.46–0.94) | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 147 (45.1) | 139 (35.8) | Ref. | - |

| Married/Cohabiting | 151 (46.3) | 211 (54.4) | 1.48 (1.08–2.02) | - |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 28 (8.6) | 38 (9.8) | 1.44 (0.84–2.46) | - |

| Circumcision | ||||

| Not Circumcised | 200 (61.0) | 254 (65.3) | Ref. | - |

| Circumcised | 128 (39.0) | 135 (34.7) | 0.83 (0.61–1.13) | - |

| Lifetime number of female sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 41 (12.6) | 57 (14.8) | Ref. | - |

| 1 | 28 (8.6) | 32 (8.3) | 0.82 (0.43–1.57) | - |

| 2–9 | 116 (35.7) | 159 (41.3) | 0.99 (0.62–1.57) | - |

| 10–49 | 117 (36.0) | 123 (32.0) | 0.76 (0.47–1.22) | - |

| +50 | 23 (7.1) | 14 (3.6) | 0.44 (0.2–0.95) | - |

| Lifetime number of male anal sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 274 (85.9) | 327 (86.3) | Ref. | - |

| 1–9 | 29 (9.1) | 34 (9.0) | 0.98 (0.58–1.65) | - |

| +10 | 16 (5.0) | 18 (4.8) | 0.94 (0.47–1.88) | - |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| MSW | 242 (74.7) | 282 (73.4) | Ref. | - |

| MSM | 8 (2.5) | 11 (2.9) | 1.18 (0.47–2.98) | - |

| MSWM | 42 (13.0) | 46 (12.0) | 0.94 (0.60–1.48) | - |

| Virgins | 32 (9.9) | 45 (11.7) | 1.21 (0.74–1.96) | - |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Current | 65 (19.9) | 77 (19.8) | 0.94 (0.64–1.37) | - |

| Former | 73 (22.3) | 73 (18.8) | 0.79 (0.54–1.15) | - |

| Never | 189 (57.8) | 239 (61.4) | Ref. | - |

| Alcoholic drinks (per month) | ||||

| 0 | 69 (21.8) | 106 (27.9) | Ref. | - |

| 1–30 | 245 (77.3) | 269 (70.8) | 0.72 (0.50–1.01) | - |

| >30 | 3 (1.0) | 5 (1.3) | 1.09 (0.25–4.69) | - |

Ref. – Reference value (1.00). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using logistic regression to assess factors associated with any β-HPV detection. Backwards elimination was used to determine factors independently associated with any β-HPV detection at each anatomic site with p value ≤ 0.20 chosen as the priori cutoff for retention in the multivariable model.

Oral β-HPV prevalence was lower compared to that at the genital and anal canal, regardless of country (Figure 2A). Men from Brazil (aOR=0.39, 95% CI 0.26–0.60) and the US (aOR=0.46, 95% CI 0.31–0.70) were significantly less likely to have at least one β-HPV type detected at the oral cavity compared to men from Mexico after adjust for age and smoking status (Figure 2A, Table 4). Older age (aOR=1.79, 95% CI 1.09–2.96 for men ages 45–70 years compared to men 18–30 years) was significantly associated with increased detection of at least one β-HPV type at the oral cavity after adjusting for country and smoking status. Finally, current (aOR=0.50, 95% CI 0.32–0.80) smokers were significantly less likely to have at least one β-HPV type detected at the oral cavity compared to men who never smoked after adjusting for age and country.

Table 4.

Demographic and sexual characteristics associated with at least one β-HPV type DNA detected in the oral cavity in 717 men participating in the HPV Infection in Men Study.

| Characteristics | Oral (N=717) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Negative (N=507) | Positive (N=210) | Unadjusted OR (95%CI) | Adjusted OR (95%CI) | |

| Country of residence | ||||

| US | 186 (36.7) | 52 (24.8) | 0.40 (0.27–0.6) | 0.39 (0.26–0.60) |

| Brazil | 181 (35.7) | 60 (28.6) | 0.47 (0.32–0.7) | 0.46 (0.31–0.70) |

| Mexico | 140 (27.6) | 98 (46.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–30 | 246 (48.5) | 79 (37.6) | Ref. | Ref. |

| 31–44 | 207 (40.8) | 91 (43.3) | 0.84 (0.58–1.22) | 1.19 (0.82–1.74) |

| 45–70 | 54 (10.7) | 40 (19.1) | 2.31 (1.43–3.73) | 1.79 (1.09–2.96) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 284 (56) | 86 (41.0) | Ref. | - |

| Black or African American | 70 (13.8) | 24 (11.4) | 1.13 (0.67–1.91) | - |

| Asian/pacific islander | 9 (1.8) | 3 (1.4) | 1.10 (0.29–4.16) | - |

| Other/mixed race | 123 (24.3) | 88 (41.9) | 2.36 (1.64–3.40) | - |

| Refused | 21 (4.1) | 9 (4.3) | 1.42 (0.63–3.20) | - |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 194 (38.6) | 117 (55.7) | Ref. | - |

| Non-Hispanic | 309 (61.4) | 93 (44.3) | 0.50 (0.36–0.69) | - |

| Education (years) | ||||

| ≤12 | 207 (41.2) | 105 (50.0) | Ref. | - |

| 13–15 | 145 (28.9) | 52 (24.8) | 0.71 (0.48–1.05) | - |

| ≥16 | 150 (29.9) | 53 (25.2) | 0.70 (0.47–1.03) | - |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single | 219 (43.5) | 67 (31.9) | Ref. | - |

| Married/Cohabiting | 239 (47.4) | 123 (58.6) | 1.68 (1.19–2.39) | - |

| Divorced/Separated/Widowed | 46 (9.1) | 20 (9.5) | 1.42 (0.79–2.57) | - |

| Circumcision | ||||

| Not Circumcised | 310 (61.1) | 144 (68.6) | Ref. | - |

| Circumcised | 197 (38.9) | 66 (31.4) | 0.72 (0.51–1.02) | - |

| Lifetime number of female sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 70 (13.9) | 28 (13.5) | Ref. | - |

| 1 | 44 (8.8) | 16 (7.7) | 0.91 (0.44–1.87) | - |

| 2–9 | 188 (37.5) | 87 (41.8) | 1.16 (0.70–1.92) | - |

| 10–49 | 171 (34.1) | 69 (33.2) | 1.01 (0.60–1.70) | - |

| +50 | 29 (5.8) | 8 (3.9) | 0.69 (0.28–1.69) | - |

| Lifetime number of male anal sex partners | ||||

| 0 | 420 (85.5) | 181 (87.4) | Ref. | - |

| 1–9 | 43 (8.8) | 20 (9.7) | 1.08 (0.62–1.89) | - |

| +10 | 28 (5.7) | 6 (2.9) | 0.50 (0.20–1.22) | - |

| Sexual orientation | ||||

| MSW | 366 (73.2) | 158 (76.0) | Ref. | - |

| MSM | 14 (2.8) | 5 (2.4) | 0.83 (0.29–2.34) | - |

| MSWM | 66 (13.2) | 22 (10.6) | 0.77 (0.46–1.30) | - |

| Virgins | 54 (10.8) | 23 (11.1) | 0.99 (0.59–1.66) | - |

| Cigarette smoking status | ||||

| Current | 111 (21.9) | 31 (14.8) | 0.58 (0.37–0.90) | 0.50 (0.32–0.80) |

| Former | 107 (21.2) | 39 (18.6) | 0.75 (0.49–1.14) | 0.74 (0.48–1.13) |

| Never | 288 (56.9) | 140 (66.7) | Ref. | Ref. |

| Alcoholic drinks (per month) | ||||

| 0 | 119 (24.1) | 56 (27.6) | Ref. | - |

| 1–30 | 368 (74.5) | 146 (71.9) | 0.84 (0.58–1.22) | - |

| >30 | 7 (1.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.30 (0.04–2.53) | - |

Ref. – Reference value (1.00). Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated using logistic regression to assess factors associated with any β-HPV detection. Backwards elimination was used to determine factors independently associated with any β-HPV detection at each anatomic site with p value ≤ 0.20 chosen as the priori cutoff for retention in the multivariable model.

Discussion

We previously reported the high prevalence of β- and γ-HPVs in the anogenital skin of HIM study participants presumably α-HPV negative by means of not hybridizing to any type-specific probe using the Linear Array methodology and thus categorized as unclassified HPV 16,17,20. We now widen our analysis to assess β-HPV prevalence at the genital and anal canal of men at the same study visit independent of α-HPV status using a methodology that allows simultaneous detection of 43 β-HPV genotypes 24. Furthermore, we report for the first time β-HPV prevalence in the oral cavity of HIM Study participants.

β-HPV DNA was detected in 77.7% of the genital specimens, similar to previously reported data in external genital lesions (EGLs) (61.1%) and preceding normal genital skin specimens of HIM participants using the Luminex technology 31. Nevertheless, these findings contrast with the 40% of β-HPV prevalence observed in male genital skin specimens using a PCR-sequencing protocol 16,32. A similar prevalence was observed regarding β-HPV detection at the anal canal of HIM participants (54.3% by Luminex versus 31.6% with PCR-sequencing) 17. Therefore, recently most studies take advantage of the higher sensitivity inherent of the Luminex technology for cutaneous HPV DNA detection (Gheit et al. 2007; Donà et al. 2015; Torres et al. 2015).

β-HPV DNA was significantly less likely to be detected at the anal canal of men from the US (48.7%) and Brazil (48.6%) compared to men from Mexico (65.6%). Using the same methodology, β-HPV DNA was observed in 65.5% and 27.2% of anal canal specimens from HIV-negative men in Spain and Italy, respectively 18,29. We found that the β-HPV prevalence in oral gargle samples was also significantly higher in Mexican men (41.2%), compared to men from Brazil (24.9%) and the US (21.9%). Overall, β-HPV prevalence in oral specimens of healthy men in the HIM Study (29.3%) was similar to a study conducted in Italy among healthy individuals (25.0%) 33, but otherwise lower than what has been observed among HIV-negative men and women with normal from the US (74%) 14. Although the small number of studies conducted to date preclude further conclusions, taken together these data suggest that β-HPV prevalence at the anal canal and oral cavity may vary widely by country and world region.

In general, we observed increased β-HPV detection with age, however this trend did not reach statistical significance for anogenital specimens. Nevertheless, these results are consistent with our prior findings using a PCR-sequencing method 17. Higher β-HPV prevalence was observed at the anal canal among middle-aged adults (31–44 years) and older men (>45 years) compared to younger men (18–30 years), whereas no age associations were observed for the external genital skin. In this same study population, men aged >45 years were also more likely to have prevalent and incident β-infection in eyebrow hairs and skin swabs 28.

The most prevalent viral types at all three anatomic sites were HPV-21 and HPV-24 (β-1), and HPV-22 and HPV-38 (β-2). Only HPV-38 has been consistently reported in the literature across multiple anatomic sites in men, including anal canal, genital, EGL, eyebrow hair and skin specimens 16–18,28,29,31. Multiple β-HPV type detection is a common finding throughout the human body and hair follicles appears to be the natural reservoir for these viruses 1,15,18,29. Our prior reports relying on PCR-sequencing indicated high prevalence of multiple β-HPV types in samples that were HPV positive by PCR but unclassified genotype due to overlapping peak patterns in sequence chromatograms 17,32. In the present study, taking advantage of the Luminex methodology which improved our ability to detect a large number of viral types at once, we confirmed that multiple β-HPVs types is a common finding, especially at the external genital skin for which up to 19 viral types were simultaneously detected. Among HIM Study participants, detection of multiple cutaneous HPV types was also a common finding on EGLs and the normal cutaneous skin 28,31.

Among behavioral factors assessed in the present study, only smoking was significantly associated with β-HPV detection in the oral cavity, where current smokers had a significantly lower likelihood of infection than never smokers. The association with smoking status was only observed at the oral cavity leading us to hypothesize that β-HPV dynamics vary by anatomic site of infection. Clearly, additional research is needed to further elucidate the biological underpinnings of these observations.

In contrast to the strong association between sexual behavior and α-HPV detection among men and women, our results, together with reports of others, suggest that sexual behaviors are not associated with the detection of cutaneous HPV types at the oral cavity and anogenital sites 16,17,28,29. A limitation of the current study is that the HIM Study questionnaire did not assess sexual behaviors regarding masturbation, rimming, or other non-penetrative sexual practices (only information about oral sex is collected). For this reason, it was not possible to evaluate the influence of direct hand, mouth, or object to penis, anal canal and mouth contact or other sexual practices that could be central to understanding the mechanisms of transmission of these viruses 34. Nevertheless, the high prevalence of β-HPV in the normal skin (67.3%) and eyebrow hairs (56.5%) of HIM Study participants enrolled in the US 28 strongly supports that detection of β-HPVs in the oral cavity and anogenital region of men may simply reflect deposition of virions shed from other body sites 35. It has to be noted that we examined only 43 of the 51 β-HPV types (see http://www.hpvcenter.se/html/refclones.html) characterized to date, and the current analysis was not extended to γ-HPV genomes. Assuming new HPV cutaneous types are continually identified, our study likely underestimated the prevalence of untested and unknown viral genotypes.

Cutaneous skin infected with specific β-HPV types have a higher susceptibility to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) induced DNA damage 28. Although recent functional studies suggest that cutaneous HPV types may also have oncogenic potential, these viruses are unlikely to cause disease at anatomic sites not exposed to UVR 31. The possible role of β-HPV as co-factors in lesion development in the genital region and oral cavity of men remains to be clarified. Larger studies with extended follow up conducted prospectively in men and women are needed.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research to [LLV]; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) [Grants numbers 13/01440-4 to LS; 13/20470-1 and 15/12557-5 to EMN; 08/57889-1 to LLV]; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tencnológico (CNPq) [Grant number 573799/2008-3 to LLV]. The infrastructure of the HIM Study cohort was supported through a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 CA098803 to ARG).

The authors would like to thank the Infections and Cancer Biology Group (International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France), HIM Study Teams in the USA (Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL), Brazil (Centro de Referência e Treinamento em DST/AIDS, Fundação Faculdade de Medicina, Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo, Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, São Paulo) and Mexico (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública, Cuernavaca). This work was supported by Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research to [LLV]; Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) [Grants numbers 13/01440-4 to LS; 13/20470-1 and 15/12557-5 to EMN; 08/57889-1 to LLV]; Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tencnológico (CNPq) [Grant number 573799/2008-3 to LLV]. The infrastructure of the HIM Study cohort was supported through a grant from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 CA098803 to ARG).

Abbreviations

- HPV

Human papillomavirus

- HIM Study

HPV Infection in Men Study

- β-HPV

beta-HPV

- α-HPV

alpha-HPV

- γ-HPV

gamma-HPV

- β-globin

beta-globin

- MSM

men who have sex with men

- MSW

men who have sex with women

- MSMW

men who have sex with men and women

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence intervals

- aOR

adjusted OR

- EGL

External Genital Lesions

- PeIN

penile intraepithelial neoplasia

Footnotes

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was given by the University of South Florida (IRB# 102660), Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Centro de Referência e Treinamento em Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis e AIDS, and Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública de México.

Conflict of Interest

ARG (IISP39582) and SLS (IISP53280) are current recipient of grant funding from Merck, and ARG and LLV are members of the Merck Advisory Board for HPV prophylactic vaccines. No conflicts of interest are declared for any of the remaining authors.

References

- 1.Antonsson A, Forslund O, Ekberg H, Sterner G, Hansson BG. The ubiquity and impressive genomic diversity of human skin papillomaviruses suggest a commensalic nature of these viruses. J Virol. 2000;74(24):11636–41. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.24.11636-11641.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Antonsson A, Karanfilovska S, Lindqvist PG, Hansson BG. General Acquisition of Human Papillomavirus Infections of Skin Occurs in Early Infancy. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41(6):2509–14. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bzhalava D, Mühr LS, Lagheden C, Ekström J, Forslund O, Dillner J, et al. Deep sequencing extends the diversity of human papillomaviruses in human skin. Sci Rep. 2014;4:1–7. doi: 10.1038/srep05807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chouhy D, Bolatti EM, Pérez GR, Giri AA. Analysis of the genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationships of putative human papillomavirus types. J Gen Virol. 2013;94(Pt 11):2480–8. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.055137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jablonska S, Dabrowski J, Jakubowicz K. Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis as a Model in Studies on the Role of Papovaviruses in Oncogenesis. Cancer Res. 1972;32(3):583–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arron ST, Ruby JG, Dybbro E, Ganem D, Derisi JL. Transcriptome Sequencing Demonstrates that Human Papillomavirus is not Active in Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(8):1745–53. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weissenborn SJ, Nindl I, Purdie K, Harwood C, Proby C, Breuer J, et al. Human papillomavirus-DNA loads in actinic keratoses exceed those in non-melanoma skin cancers. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(1):93–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23733.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. A review of human carcinogens—Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(4):321–2. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rollison DE, Pawlita M, Giuliano AR, Iannacone MR, Sondak VK, Messina JL, et al. Measures of cutaneous human papillomavirus infection in normal tissues as biomarkers of HPV in corresponding nonmelanoma skin cancers. Int J Cancer. 2008;123(10):2337–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Astori G, Lavergne D, Benton C, Höckmayr B, Egawa K, Garbe C, et al. Human papillomaviruses are commonly found in normal skin of immunocompetent hosts. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110(5):752–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1998.00191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howley Peter M, Pfister Herbert J. Beta genus papillomaviruses and skin cancer. Virology. 2015;479–480:290–6. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bzhalava D, Guan P, Franceschi S, Dillner J, Clifford G. A systematic review of the prevalence of mucosal and cutaneous human papillomavirus types. Virology. 2013;445(1–2):224–31. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chahoud J, Semaan A, Chen Y, Cao M, Rieber AG, Rady P, et al. Association Between beta-Genus Human Papillomavirus and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Immunocompetent Individuals-A Meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatology. 2015:77004. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bottalico D, Chen Z, Dunne A, Ostoloza J, McKinney S, Sun C, et al. The oral cavity contains abundant known and novel human papillomaviruses from the Betapapillomavirus and Gammapapillomavirus genera. J Infect Dis. 2011;204:787–92. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jir383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Forslund O, Johansson H, Madsen KG, Kofoed K. The nasal mucosa contains a large spectrum of human papillomavirus types from the betapapillomavirus and gammapapillomavirus genera. J Infect Dis. 2013;208(8):1335–41. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sichero L, Pierce Campbell CM, Fulp W, Ferreira S, Sobrinho JS, Baggio M, et al. High genital prevalence of cutaneous human papillomavirus DNA on male genital skin: the HPV Infection in Men Study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0677-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sichero L, Nyitray AG, Nunes EM, Nepal B, Ferreira S, Sobrinho JS, et al. Diversity of human papillomavirus in the anal canal of men: the HIM Study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(5):502–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Torres M, Gheit T, McKay-Chopin S, Rodríguez C, Romero JD, Filotico R, et al. Prevalence of beta and gamma human papillomaviruses in the anal canal of men who have sex with men is influenced by HIV status. J Clin Virol. 2015;67:47–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agalliu I, Gapstur S, Chen Z, Wang T, Anderson RL, Teras L, et al. Associations of Oral α-, β-, and γ-Human Papillomavirus Types With Risk of Incident Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;10461:1–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giuliano AR, Lazcano-Ponce E, Villa LL, Flores R, Salmeron J, Lee JH, et al. The Human Papillomavirus Infection in Men Study: Human Papillomavirus Prevalence and Type Distribution among Men Residing in Brazil, Mexico, and the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(8):2036–43. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nyitray AG, Carvalho da Silva RJ, Baggio ML, Lu B, Smith D, Abrahamsen M, et al. Age-Specific Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Anal Human Papillomavirus (HPV) among Men Who Have Sex with Women and Men Who Have Sex with Men: The HPV in Men (HIM) Study. J Infect Dis. 2011;203(1):49–57. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kreimer AR, Villa A, Nyitray AG, Abrahamsen M, Papenfuss M, Smith D, et al. The Epidemiology of Oral HPV Infection among a Multinational Sample of Healthy Men. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(1):172–82. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0682.The. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green MR, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. 4. New York: John Inglis; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmitt M, Bravo IG, Snijders JF, Gissmann L, Pawlita M, Waterboer T. Bead-based multiplex genotyping of human papillomaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(2):504–12. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.504-512.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gheit T, Billoud G, de Koning MN, Gemignani F, Forslund O, Sylla BS, et al. Development of a Sensitive and Specific Multiplex PCR Method Combined with DNA Microarray Primer Extension To Detect Betapapillomavirus Types. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(8):2537–44. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00747-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ruer JB, Pépin L, Gheit T, Vidal C, Kantelip B, Tommasino M, et al. Detection of alpha- and beta-human papillomavirus (HPV) in cutaneous melanoma: a matched and controlled study using specific multiplex PCR combined with DNA microarray primer extension. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18(10):857–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00866.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markus Schmitt, Bolormaa Dondog, Tim Waterboer, Michael Pawlita, Massimo Tommasino, Tarik Gheit. Abundance of Multiple High-Risk Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infections Found in Cervical Cells Analyzed by Use of an Ultrasensitive HPV Genotyping Assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(1):143–9. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00991-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hampras SS, Giuliano AR, Lin HY, Fisher KJ, Abrahamsen ME, McKay-Chopin S, et al. Natural History of Cutaneous Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Infection in Men: The HIM Study. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e104843. doi: 10.1080/87559129.2014.981826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donà MG, Gheit T, Latini A, Benevolo M, Torres M, Smelov V, et al. Alpha, beta and gamma Human Papillomaviruses in the anal canal of HIV-infected and uninfected men who have sex with men. J Infect. 2015;71(1):74–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saiki RK, Gelfand DH, Stoffel S, Scharf SJ, Higuchi R, Horn GT, et al. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science. 1988;239(4839):487–91. doi: 10.1126/science.2448875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce Campbell CM, Messina JL, Stoler MH, Jukic DM, Tommasino M, Gheit T, et al. Cutaneous human papillomavirus types detected on the surface of male external genital lesions: A case series within the HPV Infection in Men Study. J Clin Virol. 2013;58(4):652–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sichero L, Pierce Campbell CM, Ferreira S, Sobrinho JS, Luiza Baggio M, Galan L, et al. Broad HPV distribution in the genital region of men from the HPV infection in men (HIM) study. Virology. 2013;443(2):214–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2013.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paolini F, Rizzo C, Sperduti I, Pichi B, Mafera B, Rahimi SS, et al. Both mucosal and cutaneous papillomaviruses are in the oral cavity but only alpha genus seems to be associated with cancer. J Clin Virol. 2013;56(1):72–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu Z, Rashid T, Nyitray AG. Penises not required: a systematic review of the potential for human papillomavirus horizontal transmission that is non-sexual or does not include penile penetration. Sex Health. 2015;13(1):10–21. doi: 10.1071/SH15089. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/SH15089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hazard K, Karlsson A, Andersson K, Ekberg H, Dillner J, Forslund O. Cutaneous human papillomaviruses persist on healthy skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(1):116–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]