Abstract

Background

Digital rectal examination (DRE) is part of the assessment of trauma patients as recommended by ATLS®. The theory behind is to aid early diagnosis of potential lower intestinal, urethral and spinal cord injuries. Previous studies suggest that test characteristics of DRE are far from reliable. This study examines the correlation between DRE findings and diagnosis and whether DRE findings affect subsequent management.

Materials and methods

Patients with ICD-10 codes for spinal cord, urethral and lower intestinal injuries were identified from the trauma registry at an urban university hospital between 2007 and 2011. A retrospective review of electronic medical records was carried out to analyse DRE findings and subsequent management.

Results

253 patients met the inclusion criteria with a mean age of 44 ± 20 years and mean ISS of 26 ± 16. 160 patients had detailed DRE documentation with abnormal findings in 48%. Sensitivity rate was 0.47. Correlational analysis between examination findings and diagnosis gave a kappa of 0.12. Subsequent management was not altered in any case due to DRE findings.

Conclusion

DRE in trauma settings has low sensitivity and does not change subsequent management. Excluding or postponing this examination should therefore be considered.

Keywords: Traumatic injury, Digital rectal examination

List of abbreviations: DRE, Digital Rectal Examination; ATLS®, Advanced Trauma Life Support; GIT, gastrointestinal tract; ICD-10, International Statistical Classification of Diseases & Related Health Problems; ISS, Injury Severity Score; AIS, American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale

Highlights

-

•

There appears to be low correlation between examination and diagnosis.

-

•

Rectal examination shows poor test characteristics for detection of traumatic injury.

-

•

Digital rectal examination could be postponed following initial trauma assessment.

1. Introduction

Digital rectal examination (DRE) is carried out as part of the initial assessment of trauma patients in accordance with the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS®) concept [1]. Organised trauma protocols such as ATLS® has been developed with the intention of improving survival in the severely injured patient. DRE is performed as part of the secondary survey in order to enable early detection of lower gastrointestinal tract (GIT), urethral and spinal cord injuries. Signs indicating the presence of such injuries include positive blood per rectum, reduced or absent anal tone and a high-riding prostate, the latter two requiring a certain level of subjectivity.

The objective for this study is two-fold. Firstly, to investigate whether traumatic injuries to bowel, urethra and prostate are correctly identified through the rectal examination. Previous studies demonstrate both low rates of sensitivity and specificity for identifying these types of traumatic injuries [2]. Secondly, to assess whether the findings from the examination have any effect on subsequent management and decision-making such as whether the trauma patients is moved from assessment to the CT scanner or to the operating theatre. It has been demonstrated that whole body CT scanning both improves mortality rates [3] and reduces costs [4], compared to selective CT scanning. So if DRE does not affect management, one has to ask the question as to why we are persisting with this invasive examination as a ‘mandatory’ part of the ATLS® protocol.

2. Material and methods

This is a retrospective observational study. After obtained approval by the Institutional Ethics Review Board a retrospective medical records review of an urban university hospital trauma centre registry of a consecutive case series of trauma patients was carried out.

2.1. Participants and setting

A query on the Karolinska University Hospital's trauma database between January 2007 and December 2011 resulted in a cohort of trauma patients. This cohort was reduced in numbers after the application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria were based on all patients with ICD-10 diagnosis codes for injuries to lower GIT (S36.5), urethra (S37.3) or spinal cord (S14, S24, S34, T09.3, G95.2) resulting from both blunt and penetrating trauma. Patients were excluded if transferred from another hospital to Karolinska University Hospital for higher levels of care, if diagnosed with an isolated small bowel injury, and patients who died in the trauma room prior to the trauma team having been able to complete the full trauma assessment protocol. There were no restrictions in terms of gender or age. Consequently, data analysis is based on a subset of all trauma patients during the specified study period meeting the outlined criteria. The electronic medical records for these patients were reviewed to collect data regarding documented DRE findings in association with the initial assessment of the patient in the trauma room and for diagnosis confirmation.

2.2. Data collection and variables

Medical records were reviewed in order to identify those patients with documented DRE findings and those where the documentation for the examination was missing or not recorded. The collected information included; age, gender, diagnosis, mechanism of injury, Injury Severity Score (ISS), DRE findings and disposition of patient following completed assessment in the trauma room.

At our institution DRE is performed when the patient is log-rolled to assess if there are any injuries to the back. This is carried out either by a trauma surgery attending or senior resident as part of the E (exposure) of the ATLS protocol. The following elements of the DRE is performed: inspection for blood on the glove, palpation of the location of the prostate and the presence of anal tone. The examination is subsequently documented in the patient's electronic records as part of their ‘trauma assessment entry’. The bulbocavernous reflex is not routinely assessed. In order to avoid false positive findings, patients who were pharmacologically paralysed at the time of the initial trauma assessment were excluded from the subgroup with documented positive DRE for reduced or absent anal tone in the context of spinal injury. DRE findings were only considered positive if clearly specified in the documentation of the examination and considered negative if not stated as present. If no DRE documentation was found then the patient was included in the subgroup of patients who lacked DRE information. In this context no assumption of a normal DRE was made.

2.3. Statistical methods

Data abstraction from medical records was performed by medical professionals. Data obtained was analysed using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science; version 21). Patients were analysed as a single group for demographics and as two subgroups for subsequent analysis due to the proportion of patients lacking DRE documentation. Cohen's kappa statistic was used for correlational analysis as a measurement of agreement beyond chance between examination findings and established diagnosis where a value of zero indicates no agreement beyond chance and a value of one indicates perfect agreement.

3. Results

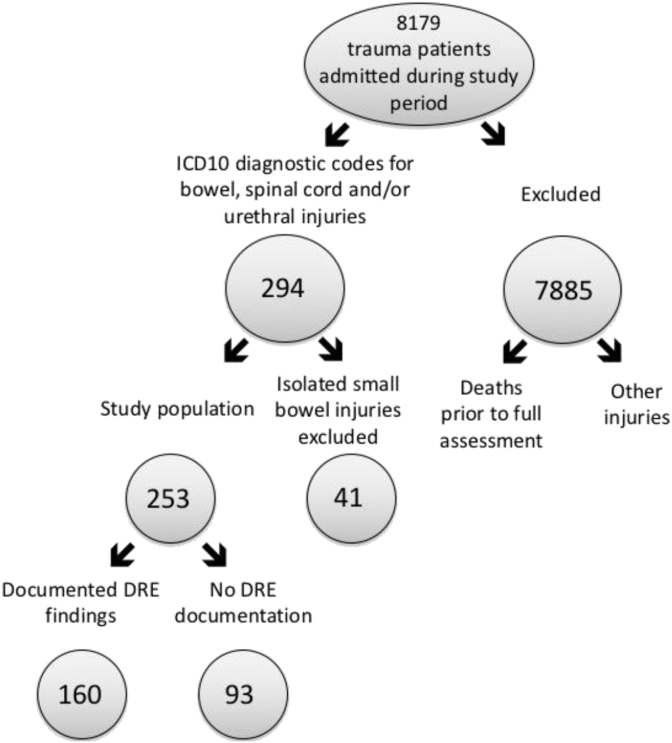

Out of 8179 trauma team activations, a total of 253 (3.1%) patients were put forward for data analysis, all with a confirmed injury in one or more organs according to the above stated inclusion criteria. The selection process is outlined in Fig. 1. The mean age was 44 ± 20 years, 75% were male and 90% of injuries were caused from blunt trauma with mean ISS of 26 ± 16. Review of medical records resulted in documented DRE findings in 160 out of 253 (63%) patients and missing DRE documentation in 93 (37%). Table 1 outlines the demographics and clinical characteristics of the total cohort with confirmed traumatic injuries.

Fig. 1.

Selection process of participating patients.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical information of the total cohort (n = 253).

| Variable | Cohort information | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender distribution (%) | 75% male; 25% female | ||||

| Injury | Type | Spinal cord | Lower intestinal | Urethral | Multiple |

| Prevalence (%) | 79% | 17% | 3% | 1% | |

| Mean Injury severity score ± SD | 26 ± 16 | ||||

| Injury mechanism (%) | 10% penetrating; 90% blunt | ||||

| Mean age ± SD | 44 ± 20 years | ||||

In the subgroup of patients with documented DRE findings, an abnormal examination was only detected in 48% of patients (n = 77) despite the fact that all of the patients in the cohort were diagnosed with at least one type of injury to either lower intestine, urethra or spinal cord. Table 2 demonstrates the sensitivity of DRE by comparing the documented finding from the examination with the actual diagnosed injury. The sensitivity rate is 0.47. Correlational analysis between DRE findings and confirmed diagnosis produced a kappa value of 0.12 reflecting a ‘slight agreement’ between the two. It is generally accepted in statistics that a kappa >0.60 denotes a substantial relationship between variables [5]. Specificity rate cannot be calculated since this study solely focuses on patients with diagnosed injuries.

Table 2.

Distribution of diagnosed injury and detection of injury through DRE.

| DRE finding (n): | Confirmed diagnosis to (n): |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower GIT (21) | Urethra (5) | Spinal cord (134) | |

| Blood (3) | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| High-riding prostate (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Reduced or absent anal tone (74) | 2 | 0 | 72 |

| Normal examination (83) | 17 | 5 | 61 |

| Total = 160 | |||

N.b. Numbers in bold indicate matching between examination findings and confirmed diagnosis.

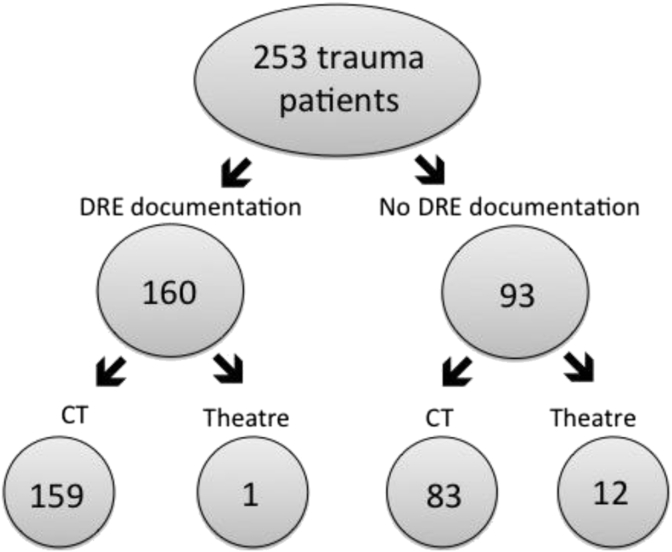

Fig. 2 outlines a comparison between the two subgroups of patients. It demonstrates that the majority of trauma patients in this cohort went straight to CT and a very small percentage were taken directly to the operating theatre. A total of 5% of the total cohort were taken directly to the operating theatre (n = 13). Most of these (n = 12) were from the subgroup without any DRE documentation. Medical records review of these 13 patients shows that the decision to go directly to the operating theatre was exclusively based on clinical deterioration due to hypotension. A review of the records for patients with documented DRE also demonstrates that identification of an abnormal finding (n = 77) does not appear to bear any impact on subsequent decision-making regarding complementary investigations e.g. sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy or retrograde urethrogram.

Fig. 2.

Disposition of patients following initial trauma assessment.

4. Discussion

DRE is currently part of the secondary survey of the ATLS® protocol. There is, however, controversy as to whether it contributes to the initial assessment of trauma patients and the degree to which the test can accurately detect early diagnosis of injuries to lower GIT, urethra and spinal cord. This study evaluates the correlation between DRE in the initial assessment of traumas and subsequent impact on diagnosis and more importantly the subsequent management.

Previous studies have demonstrated an estimated composite sensitivity of DRE to be as low as 22.9% in trauma patients [6]. Studies focusing on the sensitivity of the examination for specified injuries do not appear to demonstrate any improvement. For example, Ball et al. [7] found that the sensitivity for identifying urethral disruption from blunt trauma through DRE can be as low as 2% while alternative methods of assessment such as blood at the meatus or initial haematuria showed sensitivities ten times higher. Detection of a high-riding prostate is notoriously difficult due to limited physician exposure to this rare injury, but even for signs such as compromised anal tone, sensitivity rates still do not exceed 50% [8]. DRE evaluation has also been carried out in the paediatric population where Kristinsson et al. [9] found that sensitivity and specificity of physical examination, with or without DRE as part of it, do not differ significantly. A systematic review by Hankin et al. [2] suggests that specificity of DRE is somewhat higher with a range from 91% to 95%. Guldner et al. [10] demonstrate that DRE led to false positives in 36% of cases.

Outlined results in this study support previous findings in this field that DRE in the context of traumatic injuries provides low sensitivity rates. The correlation between DRE finding and diagnosis was 0.12 and the sensitivity rate was 0.47. Consequently, only a small proportion of diagnoses were reflected in the examination findings. Table 2 demonstrates high false negatives and this is particularly emphasised in the context of spinal cord injuries. 61 patients diagnosed with a spinal cord injury were documented as having a normal DRE. In addition, 19 patients with injury to the lower GIT were not detected through DRE. In the current study, all patients with urethral disruption were missed through DRE. These findings suggest that the DRE may in certain injuries result in limited information. It is, however, important to emphasize that the studied cohort contained a large majority of isolated spinal cord injuries resulting from blunt trauma. For example, urethral injuries were only present in 3% of the studied cohort which makes this subgroup more sensitive to bias. Consequently, we abstain from drawing any conclusions about the sensitivity of the DRE on individual type of traumatic injuries.

This study is limited by the fact that patients with no injury to spinal cord, urethra or lower GIT were excluded. This limits the possibility of analysis in terms of specificity or false positive calculations. No standardised study-specific data forms were used due to the retrospective nature of the study. DRE documentation was therefore identified through review of patient records, stated in the record entry of the team leader during the trauma assessment. Due to the reviewer relying on the assessing physicians' documentation this variability in record keeping does increase the risk of missing data. This could partly explain why 93 patients were recorded as lacking DRE documentation. A future study on this topic would benefit from a prospective design with clear DRE documentation according to a standard assessment form.

Full body CT scan including the brain, cervical spine, thorax, abdomen and pelvis has become part of the initial assessment of the multi-injured patient in most, if not all, trauma centers. The exception to the rule is if a patient is in immediate need of surgery. Of the studied cohort, a total of 13 out of 253 patients (5%) were taken directly to the operating theatre from the trauma room. 92% of these were from the subgroup that lacked DRE documentation. While this does not necessarily subtract from the purpose of the DRE, it does suggest that DRE does not play a pivotal role in immediate management decision-making in the trauma room. Of the 160 patients with DRE documentation only a single patient was taken to the operating theatre without prior CT scans. This decision was based on a clinically deteriorating hypotensive patient.

The importance of whole-body CT in improving mortality has recently been demonstrated by Caputo and colleagues [3]. However, many argue that it is a slippery slope to start excluding clinical examination from the assessment of patients and solely rely on imaging, and that DRE may have prognostic value that could guide later decision-making even if not immediately useful in early management. Katoh & el Masry [11] have shown that the best predictor of good recovery in patients with cervical cord injuries is the presence of spinothalamic sensory preservation between the level of cord injury and the last sacral dermatomes. They also demonstrated that the subgroup who showed least recovery was that which had spared rectal sensation in the DRE but lacked sacral dermatome sensation. While their study does not specifically address anal tone it does suggest that at least the sensory aspect of the rectal exam has little prognostic value in clinical outcome. A similar study was carried out by Poyton et al. [12] who demonstrated that preservation of sensation to pin-prick in the relevant dermatome, despite complete absence of power, indicated a 85% chance of motor recovery following spinal cord injury. Additionally, Singhal et al. [13] showed that Frankel classification grading [14] in combination with the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) motor scoring [15] at initial assessment were good predictors of neurological outcome. However, voluntary anal contraction is only a small component of the overall ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) and it is not possible to conclude that anal tone alone offers independent prognostic indication. To the best of our knowledge there are no studies directly testing the prognostic value of the presence of anal tone in DRE. However, with sensitivity rates that do not exceed 50% it can be discussed whether we should rely on DRE as a prognostic indicator.

5. Conclusion

Since the digital rectal examination causes no physical harm it does not need to actively be avoided should the examining physician feel it may contribute to the clinical assessment. However, it does not appear to affect immediate decision-making in the initial management of trauma patients. Presenting results in accordance with previous studies, the current study supports the conclusion that the digital rectal examination demonstrates suboptimal test characteristics in the context of detecting traumatic injuries to lower GIT, urethra and spinal cord. We therefore suggest that DRE could be deferred from the initial assessment of trauma patients and instead performed when the patient has been transferred to the ward or intensive care, yet still within the first 24 h of management. Thus, the examination does not risk increasing patient agitation or delaying subsequent management.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval has been granted for this study. It was granted by the Regional Ethics Committee Stockholm with reference number: 2014/1848-31/1.

Funding

No sponsors or external sources of funding for this study. This study was funded by the department’s own research fund.

Author contribution

The study concept and design was formed by Shahin Mohseni, Rebecka Ahl and Louis Riddez. Data collection, analysis and interpretation was carried out by Rebecka Ahl and Shahin Mohseni. The manuscript was written, edited and finally approved by all three authors.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Registration of research studies

This is a retrospective electronic records review study that did not involve or change the care or treatment of patients, as such, it is not registered.

Guarantor

Guarantor for this study is Louis Riddez, associate professor of surgery at Karolinska University Hospital.

Consent

As this is a retrospective patient records study that does not impact on the treatment or care of any patients, patient consent was not sought. This was declared to the ethics committee and approved.

Contributor Information

Rebecka Ahl, Email: rebecka.ahl@cantab.net.

Louis Riddez, Email: louis.riddez@karolinska.se.

Shahin Mohseni, Email: mohsenishahin@yahoo.com.

References

- 1.American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma Initial Assessment and Management . seventh ed. American College of Surgeons; Chicago: 2004. Advanced Trauma Life Support for Doctors; pp. 18–19. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hankin A.D., Baren J.M. Should the digital rectal examination be a part of the trauma secondary survery? Ann. Emerg. Med. 2009;53:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2008.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caputo N.D., Stahmer C., Lim G., Shah K. Whole-body computed tomographic scanning leads to better survival as opposed to selective scanning in trauma patients. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:534–539. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viera A.J., Garrett J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005;37:360–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee W.S., Parks N.A., Garcia A. Pan computed tomography versus selective computed tomography in stable, young adults after blunt trauma with moderate mechanism. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:527–533. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shlamovitz G.Z., Mower W.R., Bergman J. Poor test characteristics for the digital rectal examination in trauma patients. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2007;50:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2007.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ball C.G., Jafri S.M., Kirkpatrick A.W. Traumatic urethral injuries: does the digital rectal examination really help us? Injury. 2009;40:984–986. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guldner G.T., Brzenski A.B. The sensitivity and specificity of the digital rectal examination for detecting spinal cord injury in adult patients with blunt trauma. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2006;24:113–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kristinsson G., Wall S.P., Crain E.F. The digital rectal examination in pediatric trauma: a pilot study. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2007;32:59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guldner G., Babbitt J., Boulton M. Deferral of the rectal examination in blunt trauma patients: a clinical decision rule. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2004;11:635–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katoh S., el Masry W.S. Motor recovery of patients presenting with motor paralysis and sensory sparing following cervical spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1995;33:506–509. doi: 10.1038/sc.1995.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poyton A.R., O'Farrell D.A., Shannon F. Sparing of sensation to pin prick predicts recovery of a motor segment after injury to the spinal cord. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 1997;79-B:952–954. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b6.7939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singhal B., Mohammed A., Samuel J. Neurological outcome in surgically treated patients with incomplete closed traumatic cervical spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2008;46:603–607. doi: 10.1038/sc.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frankel H.L., Hancock D.O., Hyslop G. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia. 1969;7:179–192. doi: 10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Spinal Injury Association: ASIA Learning Center Materials – International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI) Exam Worksheet. http://www.asia-spinalinjury.org/elearning/ASIA_ISCOS_high.pdf. (accessed 23.03.15).