Introduction

Definition

Degenerative shoulder (glenohumeral) osteoarthritis is characterized by degeneration of articular cartilage and subchondral bone with narrowing of the glenohumeral joint. It causes significant pain, functional limitation and disability with an estimated prevalence of between 4% and 26%.1

Shared decision-making

The General Medical Council’s Good Medical Practice – Duties of a Doctor guide2 clearly states in the section on working in partnership with patients that doctors should:

Listen to patients and respond to their concerns and preferences.

Give patients the information they want or need in a way they can understand.

Respect patients’ right to reach decisions with the doctor about their treatment and care.

Support patients in caring for themselves to improve and maintain their health.

This can only be achieved by direct consultation between the patient and their treating clinician. Decisions about treatment taken without such direct consultation between patient and treating clinician are not appropriate because they do not adhere to principles of good medical practice.

Continuity of care

Continuity and co-ordination of care are essential parts of the General Medical Council’s Good Medical Practice guidance.2 It is therefore inappropriate for a clinician to treat a patient if there is no clear commitment from that clinician or the healthcare provider to oversee the complete care pathway of that patient, including their diagnosis, treatment, follow-up and adverse event management.

Background

The prevalence of shoulder complaints in the UK is estimated to be 14%, with 1% to 2% of adults over the age of 45 years consulting their general practitioner annually regarding new-onset shoulder pain.3 Shoulder osteoarthritis is the underlying cause of shoulder pain in 2% to 5% of this group, although few truly population-based studies have been conducted.1,4

Painful shoulders pose a substantial socio-economic burden. Disability of the shoulder can impair ability to work or perform household tasks and can result in time off work.4,5 Shoulder problems account for 2.4% of all general practitioner consultations in the UK and 4.5 million visits to physicians annually in the USA.6,7 There are a number of occupational risk factors that may be relevant in the development of shoulder pain but the available evidence is inconsistent and the associations are are not strong.8 The annual financial burden of shoulder pain management has been estimated to be US$3 billion.8

Glenohumeral arthritis: care pathway

Aims of treatment

The overall treatment aim for shoulder osteoarthritis is to relieve pain and improve function. Treatment success needs to be defined individually with patients in a shared decision-making process.

Pre-primary care (at home)

For causes of glenohumeral shoulder pain, there is potential for simple patient self-management strategies and prevention strategies at home prior to the need for a general practitioner consultation, although research to develop and assess the impact of such strategies would be needed.

Primary care/community triage services

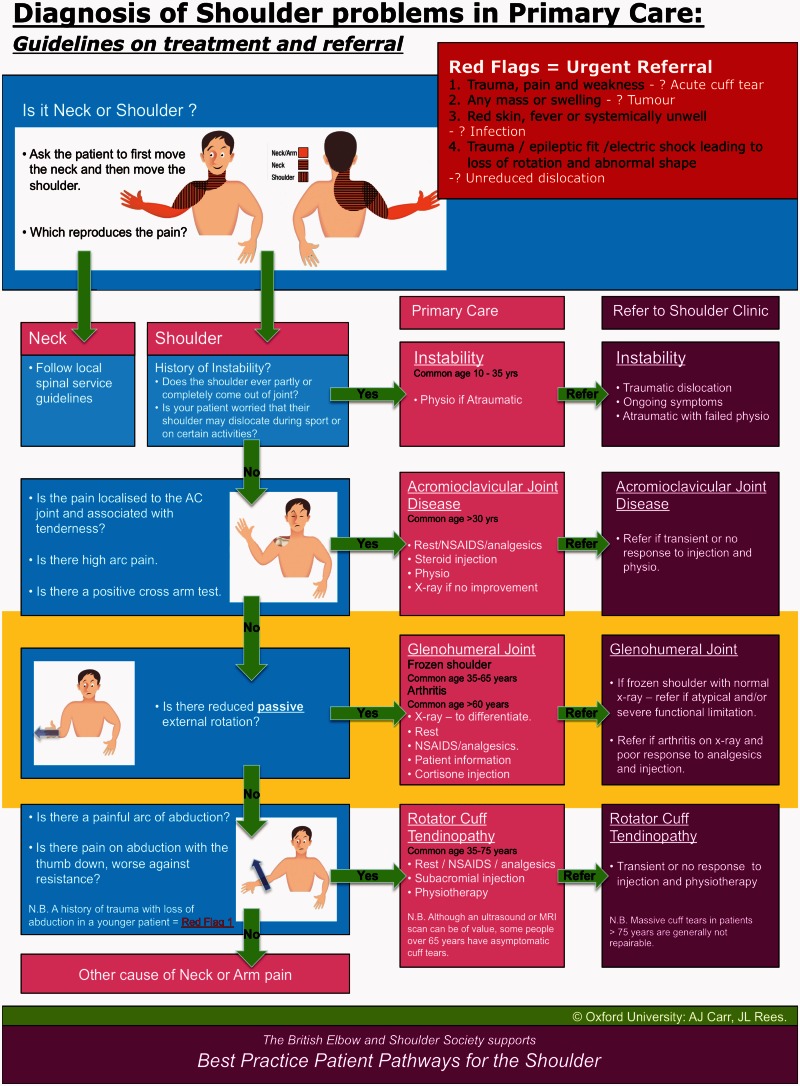

Diagnosis is based on History and Examination (see Figure 1, which gives guidance on treatment and referral).

Making the correct diagnosis is crucial, and will ensure an efficient and optimum treatment for the patient.

Plain radiographs of the shoulder are essential for confirming the diagnosis. True anteroposterior view (in scapular plane) and axillary view are recommended for this purpose. Specialist imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) scans are not indicated for treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis in primary care.

Figure 1.

Diagnosis of shoulder problems in primary care. Guidelines on treatment and referral.

Features of importance are;

Hand dominance.

Occupation and level of activity or sports.

Location, radiation and onset of pain.

Duration of symptoms.

Global reduction in range of motion, especially severe loss of passive external rotation in the affected shoulder with arm by the side.

History of multiple joint involvement or systemic manifestations.

X-rays to confirm glenohumeral arthritis, avascular necrosis or dislocation of the shoulder, which produce a similar clinical picture. X-rays are essential if there is history of significant trauma.

Red flags for the shoulder

Acute severe shoulder pain needs proper and competent diagnosis. Any shoulder ‘red flags’ identified during primary care assessment needs urgent secondary care referral.

A suspected infected joint needs same day urgent referral.

An unreduced dislocation needs same day urgent referral.

Suspected malignancy or tumour needs urgent referral following the local two-week cancer referral pathway.

Suspected inflammatory oligo or poly-arthritis or systemic inflammatory disease should be considered as a ‘rheumatological red flag’ and local rheumatology referral pathways should be followed.

Treatment in primary care and community triage services

- Treatment depends on the severity of symptoms and degree of restriction of work, domestic and leisure activities. The aims of treatment are:

- ^ Pain relief

- ^ Improving range of motion

- ^ Reducing duration of symptoms

- ^ Return to normal activities

- The following interventions are suitable for primary care:

- ^ Analgesics/non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- ^ Local injections

- ^ Acupuncture

- ^ Physical therapy

This is a painful and debilitating condition, where the pain is often severe. The onset of stiffness is progressive over many years and will cause significant functional deficit, typically presenting in patients over 60 years of age, where 32% of patients have been reported to have shoulder arthritis.9

Treatment should be tailored to individual patients’ needs depending on response and severity of symptoms.

Beware of red flags such as tumour, infection, unreduced dislocation, or inflammatory polyarthritis.

Most patients with established osteoarthritis will respond poorly to conservative treatment. The most frequent indications for invasive treatments are pain and persistent and severe functional restrictions that are resistant to conservative measures.

Failure of functional adaptation should trigger referral for consideration of surgical options.

Shared decision-making is important, and individual patients’ needs are different. Failure of initial treatment to control pain, if degree of stiffness causes considerable functional compromise, or if there is any doubt about diagnosis, prompt referral to secondary care is indicated.

Secondary care

In a UK study of patterns of referral of shoulder conditions, 22% of patients were referred to secondary care up to 3 years following initial presentation, although most referrals occurred within 3 months.9

Confirm diagnosis with history and examination.

Obtain imaging with plain radiographs to confirm the diagnosis of glenohumeral osteoarthritis, to rule out other differentials such as avascular necrosis of humeral head (without arthritis) or dislocation and to exclude other pathology that might also be contributing to the shoulder pain such as acromioclavicular joint arthritis. Specialist imaging with ultrasound, CT or MRI scans may be indicated for evaluation of the state of the rotator cuff and bone stock as well as to aid pre-operative planning.

Counsel patient fully regarding surgical and nonsurgical options.

Ensure multidisciplinary approach to care with availability of specialist physiotherapists and shoulder surgeons.

- The following nonsurgical interventions maybe considered in secondary care for temporary alleviation of symptoms, for example where surgery is not desired, contraindicated or needs to be delayed:

- ^ Glucocorticoid injection

- ^ Sodium hyaluronate therapy

- ^ Autologous platelet preparations

- ^ Nerve blocks or local injections

If symptoms fail to resolve with nonsurgical treatment, then arthroscopic or open surgical interventions may be considered. This choice depends mainly on clinical indication and surgical expertise.

- Surgical secondary care interventions include:

- ^ Arthroscopic interventions including debridement with or without biological resurfacing.

- ^ Biological glenoid resurfacing with hemiarthroplasty

- ^ Hemiarthroplasty (including resurfacing)

- ^ Total shoulder replacement (TSR)

Arthroscopic debridement is performed under general anaesthesia. The surgery aims to remove loose bodies, osteophytes, treat damage to articular cartilage with microfracture techniques and release the contracted capsule. This potentially may reduce pain and improve range of movement. This procedure may be appropriate for younger patients with early arthritis.

Suprascapular nerve block can be performed by either by single or series of injections or by nerve ablation (percutaneous or arthroscopic) and is a purely pain relieving intervention. It is thought that the suprascapular nerve is sensory to the shoulder capsule and nerve block therefore reduces symptoms of pain. This intervention is not an alternative to shoulder replacement for definitive treatment of arthritis.

Biological glenoid resurfacing is a technique used particularly in younger patients. This can be in conjunction with a shoulder hemiarthroplasty in order to avoid the insertion of a glenoid component. The technique can also be performed arthroscopically. Described methods include the use of biological material, for example meniscal allograft or semi-synthetic material using typically human dermis or alternative xenografts as an interposition arthroplasty, glenoid microfracture or a glenoid reaming debridement technique.

Hemiarthroplasty, TSR and reverse shoulder replacement are arthroplasty procedures performed under general anaesthesia with or without regional anaesthesia. They may be stemmed, stemless or resurfacing and may be cemented, uncemented or a combination of both. Hemiarthroplasty addresses only the humeral arthritis. By contrast, TSR and reverse shoulder replacements address arthritis on both humeral and glenoid sides of the joint. TSR is used for patients with an intact rotator cuff, whereas reverse shoulder replacement is reserved for patients with cuff tear arthropathy or older patients with a torn or insufficient cuff.

- It would be expected that surgical units performing surgery for shoulder osteoarthritis:

- ^ Ensure patients undergo appropriate pre-operative assessment to ensure fitness for surgery and to confirm discharge planning

- ^ Perform surgery in appropriately resourced and staffed units

- ^ Have access to specialist anaesthesia services including availability of nerve blocks for postoperative pain relief

- ^ Have radiology services available during the peri-operative period

- ^ Have arrangements for adequate postoperative physiotherapy and appropriate follow-up as clinically indicated

- ^ Have suitable resources to manage surgical and medical complications

Linked metrics

Alternative model

Arthroscopic debridement

Diagnosis Codes M19.0, M19.1, M19.2

Procedure Codes (OPCS 4.7) – Y76.7, W80.8, W80.9

Hemiarthroplasty of head of humerus

Diagnosis Codes M19.0, M19.1, M19.2

Procedure Codes (OPCS 4.7) W49.1, W49.4, W49.8, W50.9, W51.1, W51.8, W51.5, W51.8, W51.9

Total prosthetic replacement of shoulder joint

Diagnosis Codes M19.0, M19.1, M19.2

Procedure Codes (OPCS 4.7) W96.1,W96.8, W97.1, W97.8, W97.9, W98.1, W98.8, W98.9, W49.9, W50.1, W50.4, W50.8

Hybrid prosthetic replacement of shoulder joint

Diagnosis Codes M19.0, M19.1, M19.2

Procedure Codes (OPCS 4.7) O06.1, O06.8,O06.9, O07.1, O07.8, O07.9, O08.1, O08.8, O08.9

Outcome metrics

For shoulder arthroplasty, details on patient demographics, shoulder pathology, arthroplasty type and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) are now entered onto the National Joint Registry.

Length of stay.

Re-admission rate within 90 days.

PROM pre-procedure, and minimum 6 months post procedure.

Infection/other adverse events.

Revision of prosthetic replacement.

Research and audit

PROM: a validated clinical score, preferably a PROM should be used pre-operatively and following treatment.

Acceptable scores include the Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand, Constant Score and the Oxford Shoulder Score. Other measures such as EQ5D may be used for economic analysis.

Scores should be captured pre-operatively and a minimum of 6 months following intervention, which allows longitudinal analysis to determine magnitude of treatment effect and consequences of any treatment-related adverse events.

Arthroplasty or replacement procedures should be entered onto the National Joint Registry to monitor outcomes, complications and longer-term survivorship of implanted prostheses.

Patient/public/clinician information

Patient and public information: ensure all available information is provided regarding the benefits and risks of all treatment options.

Clinician information: ensure access to available evidence.

Evidence: shoulder osteoarthritis

Evidence for effectiveness and cost effectiveness of non-invasive treatment

It is important to note that the evidence to support conservative treatments and the advantages between different treatments remains limited. Until evidence becomes available, clinical and shared decision-making on accessing available interventions is based on level of symptoms and functional restrictions is recommend.

Additionally, the effectiveness of many nonsurgical interventions has been investigated in terms of improvement in shoulder pain in relation to the entire spectrum of shoulder conditions. Therefore, despite not being proven to be effective in the management of shoulder arthritis specifically, such interventions as acupuncture or injections maybe effective in symptom control from arthritis as opposed to management of the disease process itself.

Oral drug treatment

There is strong evidence for the use of oral paracetamol given regularly to modify the pain caused osteoarthritis in general.10 Paracetamol is safe and has a minimal adverse effect profile. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications also have proven effectiveness in the management of osteoarthritis in general because they reduce pain associated with inflammation and synovitis, although they are not recommended as first-line medication as a result of a significant adverse effect profile.11 Similarly, opiate-based analgesia, although shown to be effective for pain relief, is not recommended for long-term use due the adverse effect profile and the risk of dependence.12

Corticosteroid injections

There is no evidence to support the routine use of corticosteroid injections for the management of shoulder arthritis.13 What evidence supporting the use of such agents comes from the literature relating to the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. However, as above, corticosteroid injections may have a short-term effect of up to 1 month, which could make them useful as a diagnostic aid when shoulder arthritis presents with concomitant pathology or for managing an acute exacerbation of pain as a result of inflammation within the joint.

Sodium hyaluronate injection

Blaine et al.14 published a randomized controlled trial (RCT) comparing the use of weekly saline injections for five weeks with a series of three or five sodium hyaluronate injections for shoulder pain. Patients had multiple pathologies but, of the 660 patients enrolled in the study, 398 had osteoarthritis. The study found statistically significant improvement in visual analogue scale (VAS) scores at the 7 weeks and 26 weeks time points in patients with shoulder arthritis with/without rotator cuff tear. However, the maximum follow-up period was 26 weeks and thus no data are available with respect to the longer term.14

Additionally, Merolla et al.15 completed a retrospective cohort study comparing the outcome of two cohorts undergoing glenohumeral injection for shoulder arthritis. Forty-one and 51 patients had received corticosteroid therapy and hyaluronate therapy, respectively. Those patients in the hyaluronate group had statistically better VAS, Constant–Murley and Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) scores in comparison to pre-intervention scores at time points 1 month, 3 months and 6 months. By contrast, patients in the corticosteroid group had no improvement 1 month post injection for any of the parameters.15

Autologous platelet preparations

There is no evidence to support the use of platelet gel or platelet-poor products in the management of shoulder arthritis. Again, evidence for the use of these products comes from the literature relating to the management of knee osteoarthritis, of which Level 1 evidence is present.16 Clinical trials comparing the using of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) preparations with hyaluronic acid preparations have shown superior outcome in terms of pain relief, reduction in stiffness and functional improvement in the PRP group, with a follow-up of up to 24 months.17 It is considered that these agents allow tissue generation and growth through a process of inflammation, cell proliferation and remodeling. This treatment method may be the focus of future research, with the development of well-designed clinical trials specific to the non-operative management of shoulder osteoarthritis.

Acupuncture

Lathia et al.18 conducted a RCT looking at the role of acupuncture in the treatment of chronic shoulder pain. The groups included a control versus two different forms of acupuncture. The patients in the acupuncture groups had statistically significant improvement in SPADI scores.18 However, the patients had a variety of pathologies (e.g. frozen shoulder, impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears) and so the results cannot be extrapolated to recommend the use of acupuncture in shoulder arthritis.

Suprascapular nerve block or ablation

Several studies have demonstrated short-term benefit from suprascapular nerve block for a variety of shoulder conditions, including shoulder osteoarthritis, frozen shoulder, rheumatoid arthritis, rotator cuff tears. Most studies have demonstrated improvement of up to 12 weeks post intervention. In cases of arthritis, this may be diagnostic but, because the injection is relatively safe, this can be repeated if required. Although evidence for these interventions is limited to case series, there are several studies in the literature; therefore, suprascapular nerve modulation is useful in the management of shoulder symptoms, in the short-term in most cases.19 Suprascapular nerve ablation is not indicated and should not be performed for glenohumeral osteoarthritis with an intact rotator cuff.

Evidence regarding the effectiveness of surgery

Arthroscopic debridement

Namdari et al.20 conducted a literature review on the role of arthroscopic debridement in the management of shoulder arthritis. After exclusions, only five studies were deemed suitable for analysis all of which were appraised at level IV evidence. In total, 245 shoulders were included. Patients reported statistically significant improvement in range of motion from forward flexion of 136° and 36° external rotation to 159° and 58°, respectively. Functional outcome, satisfaction and pain scores used differed between series included in the review but had improved in all series included in the study. Thirteen percent of patients from all included series were ‘converted’ to a shoulder arthroplasty procedure at a mean of 13 months.20 The study concluded that arthroscopic management does not have sufficient quality evidence to support its routine use. However, because of the short-term benefit of reduced pain and improved function, it maybe useful in a younger cohort of patient who are looking for joint-preserving options for advanced osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint.21

Shoulder (replacement) arthroplasty

Shoulder replacement surgery is an established and effective surgical treatment for glenohumeral arthritis. Hemiarthroplasty or TSR provides significant improvement in pain, global health assessment, function and quality-of-life scores, as demonstrated in the medical literature.22–24 These benefits are comparable to other surgical treatments in orthopaedic surgery (e.g. total hip replacement and other interventions in medicine, generally including coronary artery bypass grafting).25

Biological glenoid resurfacing with or without hemiarthroplasty

Namdari et al.26 performed a systematic review to critically examine the outcomes of biological glenoid resurfacing in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Seven level IV case series were included in the review: 128 patients underwent glenoid resurfacing with hemiarthroplasty and 52 patients underwent arthroscopic glenoid resurfacing, giving a total of 180 patients. The mean age was 46 years. Pre-operative indications for resurfacing were multiple and not limited to primary osteoarthritis. There were no control groups in any of the studies chosen. Patients were followed up for a mean of 46.6 months. Outcome measures reported were multiple with no uniformity amongst studies. Statistically significant improvements were found in most outcome measures evaluated postoperatively, which indicated that resurfacing can be successful in the short term; however, little evidence exists with respect to the long-term results. The overall complication rate was 13.3% and the reoperation rate was 26%, which is higher than reported values for other treatment options. It is suggested that biological glenoid resurfacing could be a good alternative treatment for young patients with glenohumeral arthritis because it avoids many of the concerns associated with TSR in that age group. It was found that, as a result of the quality of the primary studies and inconsistencies in reporting outcomes, it is not possible to draw meaningful conclusions to confirm or refute this. None of the studies evaluated compared resurfacing to other treatments. Many patients had already undergone at least one previous shoulder surgery prior to resurfacing and it is not clear what influence this may have on outcome, complications and reoperation rates. All studies lacked the power to define outcomes based on individual aetiologies for resurfacing.26

Additional case series focusing on biological resurfacing have consistently produced unsatisfactory longer-terms results, using a variety of materials including dermal and meniscal allografts. Puskas et al.27 reported an 83% revision rate with dermal allograft at a mean of 16 months. In the meniscal group, the revision rate was 60% at 22 months. Similarly Hammond et al.28 compared the results of two cohorts of patients, one having undergone hemiarthroplasty and the second hemiarthroplasty with biological resurfacing. The revision rates were 26% and 60%, respectively.

Current evidence does not support the use of biological glenoid resurfacing using interposition arthroplasty for shoulder osteoarthritis, with or without the use of hemiarthroplasty.

Microfracture of the glenoid and humerus have demonstrated improvement in pain and function for focal cartilage defects.29 The greatest improvement was in small defects on the humeral side, with less benefit for lesions on both sides of the glenohumeral articulation. Microfracture replaces normal articular cartilage with fibrocartilage, as demonstrated by studies in the knee. Although there is evidence to support microfracture, there is currently no evidence supporting glenoid microfracture in conjunction with hemiarthroplasty.30

Reaming techniques of the glenoid in younger patients of less than 55 years of age have demonstrated improvements in pain and function when utilized with hemiarthroplasty. Concentric reaming at described by Saltzman et al.31 in 65 patients showed improvement in pain and function. Similarly, Clinton et al.32 published a case–control study with 35 patients comparing a ‘ream and run’ technique with TSR, demonstrating similar improvement in pain and function in both patient groups.

Humeral head resurfacing arthroplasty

Humeral head resurfacing has been shown in multiple case series to reduce pain and improve function in patients with osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint. Maximum follow-up in these series extends to a mean of 28 years (21 years to 40 years).33 Although glenoid access may be difficult to achieve without humeral head removal, TSR and hemiarthroplasty have been reported using resurfacing in osteoarthritis, with similar results reported at 7 years in a population group with a mean age of 72 years.34. In the longer term, glenoid erosion, as with other forms of hemiarthroplasty (stemmed and stemless), may be seen and has been reported in 12% of cases at 4 years radiologically.35

The cumulative 5-year revision rates following humeral resurfacing from the Australian36 and Danish arthroplasty registers37 have been reported as 11.2% and 9.9%, respectively. The Danish report, however, makes the observation: ‘The difference in the rate of revision between resurfacing hemiarthroplasty and stemmed hemiarthroplasty may also be influenced by the fact that the resurfacing procedure can be more easily revised than other designs of arthroplasty. This will thus favour other designs when the rates of revision are compared’.

Resurfacing has been recommended particularly in younger patients to preserve bone stock where implanting a polyethylene glenoid prosthesis with potential wear and failure needs to be weighed against the potential long-term risk of glenoid erosion sometimes seen in hemiarthroplasty.33–35,38

Stemless shoulder arthroplasty

Stemless shoulder replacement is the latest development to combat potential stem related problems in shoulder arthroplasty. The concept allows the resection of the humeral head to facilitate glenoid exposure to insert a glenoid prosthesis to perform a TSR, which is more technically demanding in conventional surface replacement arthroplasty.

The number of stemless implants reported in the literature is small and follow-up remains limited. All but one published case series available quote less than 4 years of mean follow-up, for both hemiarthroplasty39 and TSR.39–41 One report describes 39 patients treated for osteoarthritis with a mean follow-up of 68 months showing similar results achieved using hemiarthroplasty and TSR.42 In the short and medium term, the results reported for stemless arthroplasty appear to be comparable to conventional stemmed arthroplasty surgery.40,42

Hemiarthroplasty versus anatomical TSR

Most of the literature on surgical interventions focuses on the debate about TSR versus resurfacing or stemmed hemiarthroplasty. Although the studies so far report consistent improvements in patient quality-of-life and shoulder function following shoulder replacement, well-designed studies are required to determine which implant provides most benefit in specific types of pathology. The conclusions drawn by the current literature should therefore be interpreted with a degree of caution.

Fevang et al.43 reported the outcomes of patients treated with shoulder arthroplasty using data from the Norwegian arthroplasty register. They observed significantly better functional and quality-of-life outcomes in patients with osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint treated with TSR compared to either stemmed or resurfacing hemiarthroplasty. A shortcoming of their study was the response rate of 65%. There is also no information provided concerning the state of the rotator cuff in these patient groups.

Rasmussen et al.44 compared the patient-reported outcomes and revision rates of humeral resurfacing with stemmed hemiarthroplasty and TSR using data from the Danish shoulder arthroplasty register. They found that patients treated with TSR had a better Western Ontario Osteoarthritis Index score at 1 year compared to humeral resurfacing and stemmed hemiarthroplasty. There was no difference in the revision rate between the groups.

Gartsman et al.45 randomized 51 shoulders to stemmed hemiarthroplasty or TSR for osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint and reported the results in 2000 at a mean of 35 months follow-up. There was no difference in the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) outcome scores, although the TSR group achieved significantly better pain relief and internal rotation compared to the hemiarthroplasty group. Furthermore, during the follow-up period, three of 24 patients in the hemiarthroplasty group required revision with glenoid resurfacing for progressive and painful glenoid erosion, whereas there were no revisions in the TSR group.

Edwards et al.46 reported a multi-centre study comparing 601 TSRs with 89 stemmed hemiarthroplasties. The study compared constant score, active forward elevation and external rotation in patients with a minimum follow-up of 2 years. It was found that the functional outcome measures in those undergoing TSR were significantly better than those undergoing hemiarthroplasty. There was no significant difference in pain scores between the two groups. However, a substantially higher revision rate was reported in the TSR group, which was explained by the use of metal-backed glenoid components in 238 patients. The overall revision rate at 7 years was 30% in the TSR group versus 4% in the hemiarthroplasty group.

Radnay et al.47 performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of 23 studies, including that of Gartsman et al.45, totalling 1952 patients, evaluating TSR and stemmed hemiarthroplasty. The findings showed that, compared with hemiarthroplasty, TSR provided statistically significant improvement in pain relief, forward elevation, external rotation and patient satisfaction. Revision rates were reported as 10.2% for hemiarthroplasties as opposed to 6.5% for TSR. Some 8.1% of Hemiarthroplasties required conversion to TSR as a result of pain, suggesting the glenoid progressively erodes over time resulting in worsening outcomes. In TSR, the type of glenoid component employed appeared to have an impact on revision rates with 6.8% of TSRs with metal backed glenoids requiring revision compared to 1.7% of TSRs with all-polyethylene glenoids. However, a low level of evidence was noted for the majority of studies evaluated (mean level of evidence 3.73) and therefore caution is advised with respect to any conclusions drawn.

Lo et al.23 performed a prospective trial with 42 patients randomized to receive either TSR or stemmed hemiarthroplasty. The patients were followed up for 2 years and assessed using a number of validated shoulder scores, as well as a pain score. Significant improvements were found in all domains for both patient groups, although there was no statistical difference between TSR and hemiarthroplasty groups. Of the 20 patients randomized to hemiarthroplasty, three patients had persistent pain from glenoid arthrosis and two of these were revised to a TSR, whereas the third patient was considering revision within the 2-year follow-up period. The shortcomings of the trial are low patient numbers and follow-up length.

Bryant et al.48 performed a systematic review in 2005 and meta-analysis of four studies, including both those of Gartsman et al.45 and Lo et al.23, totalling 112 patients. Their finding were similar to those of Radnay et al.47 TSR showed a significantly better improvement over stemmed hemiarthroplasty in the UCLA shoulder score, pain score and forward elevation. It is noted that all of the studies included in the review had design weaknesses and thus any conclusions drawn should be considered with caution.

Sandow et al.49, when reporting on the results of a randomized study comparing stemmed hemiarthroplasty with TSR in patients with osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint with an intact rotator cuff at a minimum follow-up of 10 years, observed that patients in the TSR group had less pain and better function at 2 years and there was no substantial deterioration in function at 10 years. Furthermore, none of the hemiarthroplasty patients were pain-free at 10 years, whereas approximately half the TSR patients were pain-free. The revision rate in the hemiarthroplasty group was 31% compared to 10% for the TSR group and revision of hemiarthroplasty to TSR was challenging as a result of glenoid erosion.

Singh et al.50 performed a Cochrane review on surgery for shoulder osteoarthritis. They included seven studies with 238 patients who were RCTs/quasi-RCTs. Their reported findings were that TSR provided significantly better American Shoulder and Elbow Society (ASES) functional scores than stemmed hemiarthroplasty. Pain and quality-of-life scores were, however, not significantly different. It should be noted that this assumption was based on the results from only one paper of the seven reviewed. Equally, revision rates were found to be higher with hemiarthroplasty based on the findings of one paper.

Izquierdo et al.22 provided an American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guideline based on a thorough literature search. The quality of scientific data found on interventions for glenohumeral osteoarthritis was noted to be poor. Nineteen suitable studies were found, which were used to formulate recommendations. Many interventions commonly used in clinical practice were found not to have any evidence of suitable quality to afford recommendation. Weak and moderate evidence was found to support the use of surgery. Weak evidence supported the use of TSR and stemmed hemiarthroplasty. Moderate evidence was found to suggest that TSR is preferable to stemmed hemiarthroplasty in terms of improvement in global health assessment score and pain scores; however, functional and quality-of-life outcomes were no different.

Cemented versus uncemented stems in TSR

Lichfield et al.51 performed a double-blind RCT across seven tertiary centres in Canada to evaluate cemented versus uncemented humeral components. In total, 161 patients were randomized intra-operatively to receive either cemented humeral stem or uncemented press fit stem. The implant used was the same and patients were followed up for 2 years. The study showed that the group receiving a cemented stem had a significantly better Western Ontario Osteoarthritis Shoulder index score. Two other outcome measures used did not detect any difference (McMaster-Toronto Arthritis Patient Preference Disability Questionnaire; ASES). Range of motion and strength improvement were similar for both groups. Baseline epidemiological data were well matched, apart from the sex ratios of the two groups, with more males in the cemented group and more females in the uncemented group. It was suggested that the perceived benefits found in the cemented group may be sex-specific towards males. It is of note that only one TSR went on to revision.

Revision rates for TSR

Singh et al.52 used the Mayo Clinic Total Joint Registry to conduct a study on revision surgery following TSR. A total of 2588 joints were analyzed between 1976 and 2008 with up to a 20-year follow-up. The study included TSR performed for a number of diagnoses; thus, it is difficult to extract data pertaining solely to TSR performed for osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis was the underlying diagnosis for 1640 joints of which 114 underwent revision over the 20-year period. This equates to 81% of TSRs surviving 20 years. It is not possible from the study to define risk factors for the osteoarthritis group; however, it was generally found that male sex, underlying rotator cuff disease and tumour where associated with increased risk of revision. Body mass index and comorbidity were not found to increase revision risk.

Overall effectiveness of available treatments

Oral drug treatment

- Likely to be beneficial.

- ^ Oral paracetamol

- ^ NSAIDs

Local injections

- Likely to be beneficial.

- ^ Sodium hyaluronate

- ^ Suprascapular nerve block

- Unknown effectiveness.

- ^ Platelet-derived products

Non-drug treatment

Unknown effectiveness.

Acupuncture

Surgery

- Known effectiveness.

- ^ Hemiarthroplasty (humeral head resurfacing, stemless and stemmed)

- ^ Anatomical TSR

- Unknown effectiveness.

- ^ Arthroscopic debridement

- ^ Biological glenoid resurfacing

Summary

The scope of this Patient Care Pathway has been to summarize the evidence on the management of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. Other aetiologies of shoulder arthritis include inflammatory, avascular necrosis, cuff failure and sequelae of trauma. A comprehensive review of the evidence in relation to these aetiologies is beyond the scope of the present article but is likely to be the focus of future evidence-based care pathways.

Acknowledgements

Contributions from the BESS Working Group: Michael Thomas, Amit Bidwai, Amar Rangan, Jonathan Rees, Peter Brownson, Duncan Tennent, Clare Connor and Rohit Kulkarni.

Contributions from the BOA Guidance Development Group: Rohit Kulkarni (Chair), Jonathan Rees, Andrew Carr, Chris Deighton, Vipul Patel, Federico Moscogiuri, Jo Gibson, Clare Connor, Tim Holt, Chris Newsome and Mark Worthing.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Royal College of General Practitioners; Office of Populations, Censuses and Surveys. Third national morbidity survey in general practice, 1980–1981; Department of Health and Social Security, series MB5 No 1, London: HMSO, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Good Medical Practice. http://www.gmc-uk.org/guidance/good_medical_practice.asp (accessed 26 December 2014).

- 3.Urwin M, Symmons D, Allison T, et al. Estimating the burden of musculoskeletal disorders in the community: the comparative prevalence of symptoms at different anatomical sites, and the relation to social deprivation. Ann Rheum Dis 1998; 557: 649–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harkness EF, Macfarlane GJ, Nahit ES, Silman AJ, McBeth J. Mechanical and psychosocial factors predict new onsent shoulder pain: A prospective cohort study of newly employed workers. Occup Environ Med 2003; 60: 850–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van der Windt D, Thomas E, Pope DP, et al. Occupational risk factors for shoulder pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med 2000; 57: 433–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linsell L, Dawson J, Zondervan K, et al. Prevalence and incidence of adults consulting for shoulder conditions in UK primary care; patterns of diagnosis and referral. Rheumatology 2006; 45: 215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oh LS, Wolf BR, Hall MP, Levy BA, Marx RG. Indications for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007; 455: 52–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Windt DA, Koes BW, Boeke AJ, Devillé W, De Jong BA, Bouter LM. Shoulder disorders in general practice: prognostic indicators of outcome. Br J Gen Pract 1996; 46: 519–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chillemi C and Francesschini V. Shoulder osteoarthritis. Arthritis 2013; 370213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Bijlsma JW. Analgesia and the patient with osteoarthritis. Am J Ther 2002; 9: 189–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Seed SM, Dunican KC, Lynch AM. Osteoarthritis: a review of treatment options. Geriatrics 2009; 64: 20–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jawad AS. Analgesics and osteoarthritis: are treatment guidelines reflected in clinical practice? Am J Ther 2005; 12: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross C, Dhawan A, Harwood D, Gochanour E, Romeo A. Glenohumeral joint injections: a review. Sports Health 2013; 5: 153–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blaine T, Moskowitz R, Udell J, et al. Treatment of persistent shoulder pain with sodium hyaluronate: a randomized, controlled trial. A multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008; 90: 970–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merolla G, Sperling JW, Paladini P, Porcellini G. Efficacy of Hylan G-F 20 versus 6-methylprednisolone acetate in painful shoulder osteoarthritis: a retrospective controlled trial. Musculoskelet Surg 2011; 95: 215–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xie X, Zhang C, Tuan RS. Biology of platelet-rich plasma and its clinical application in cartilage repair. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16: 204–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu Y, Yuan M, Meng HY, et al. Basic science and clinical application of platelet-rich plasma for cartilage defects and osteoarthritis: a review. Osteoarthr Cartilage 2013; 21: 1627–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lathia AT, Jung SM, Chen LX. Efficacy of acupuncture as a treatment for chronic shoulder pain. J Altern Complement Med 2009; 15: 613–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jang JS, Choi HJ, Kang SH, Yang JS, Lee JJ, Hwang SM. Effect of pulsed radiofrequency neuromodulation on clinical improvements in the patients of chronic intractable shoulder pain. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2013; 54: 507–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Namdari S, Skelley N, Keener JD, Galatz LM, Yamaguchi K. What is the role of arthroscopic debridement for glenohumeral arthritis? A critical examination of the literature. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 1392–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millett PJ, Horan MP, Pennock AT, Rios D. Comprehensive Arthroscopic Management (CAM) procedure: clinical results of a joint-preserving arthroscopic treatment for young, active patients with advanced shoulder osteoarthritis. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 440–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Izquierdo R, Voloshin I, Edwards S, et al. Treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2010; 18: 375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo IKY, Litchfield RB, Griffin S, Faber K, Patterson SD, Kirkley A. Quality-of-life outcome following hemiarthroplasty or total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis. A prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 2178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norris TR, Iannotti JP. Functional outcome after shoulder arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis: a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2002; 11: 130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boorman RS, Kopjar B, Fehringer E, Churchill RS, Smith K and Matsen FA III. The effect of total shoulder arthroplasty on self-assessed health status is comparable to that of total hip arthroplasty and coronary artery bypass grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12: 158–163. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Namdari S, Alosh H, Baldwin K, Glaser D, Kelly JD. Biological glenoid resurfacing for glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 1184–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puskas GJ, Meyer DC, Lebschi JA, Gerber C. Unacceptable failure of hemiarthroplasty combined with biological glenoid resurfacing in the treatment of glenohumeral arthritis in the young. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 1900–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond LC, Lin EC, Harwood DP, et al. Clinical outcomes of hemiarthroplasty and biological resurfacing in patients aged younger than 50 years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22: 1345–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van der Meijden OA, Gaskill TR, Millett PJ. Glenohumeral joint preservation: a review of management options for young, active patients with osteoarthritis. Adv Orthop 2012. Article ID 160923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bhatia S, Hsu A, Emery CL, et al. Surgical treatment options for the young and active middle-aged patient with glenohumeral arthritis. Adv Orthop 2012. Article ID 846843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saltzman MD, Chamberlain AM, Mercer DM, Warme WJ, Bertelsen AL, Matsen FA., III Shoulder hemiarthroplasty with concentric glenoid reaming in patients 55 years old or less. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 609–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clinton J, Franta AK, Lenters TR, Mounce D, Matsen FA., III Nonprosthetic glenoid arthroplasty with humeral hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty yield similar self-assessed outcomes in the management of comparable patients with glenohumeral arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16: 534–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pritchett JW. Long-term results and patient satisfaction after shoulder resurfacing. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 771–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy O, Copeland SA. Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty (Copeland CSRA) for osteoarthritis of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004; 13: 266–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alizadehkhaiyat O, Kyriakos A, Singer MS, Frostick SP. Outcome of Copeland shoulder resurfacing arthroplasty with a 4-year mean follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22: 1352–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Graves S. National Joint Replacement Registry – Shoulder arthroplasty annual report 2015. Australian Orthopaedic Association.https://aoanjrr.dmac.adelaide.edu.au/documents/10180/217645/Shoulder%20Arthroplasty.

- 37.Rasmussen JV, Polk A, Sorensen AK, Olsen BS, Brorson S. Outcome, revision rate and indication for revision following resurfacing hemiarthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the shoulder 837 operations reported to the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry. Bone Joint J 2014; 96: 519–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Hadithy N, Domos P, Sewell MD, Naleem A, Papanna MC, Pandit R. Cementless surface replacement arthroplasty of the shoulder for osteoarthritis: results of fifty Mark III Copeland prosthesis from an independent center with four-year mean follow-up. Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012; 21: 1776–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huguet D, DeClercq G, Rio B, Teissier J, Zipoli B. Results of a new stemless shoulder prosthesis: radiologic proof of maintained fixation and stability after a minimum of three years’ follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 19: 847–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bell SN, Coghlan JA. Short stem shoulder replacement. Int J Shoulder Surg 2014; 8: 72–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berth A, Pap G. Stemless shoulder prosthesis versus conventional anatomic shoulder prosthesis in patients with osteoarthritis: a comparison of the functional outcome after a minimum of two years follow-up. J Orthop Traumatol 2013; 14: 31–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Habermeyer P, Lichtenberg S, Tauber M, Magosh M. Midterm results of stemless shoulder arthroplasty: a prospective study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 1463–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fevang B-TS, Lygre SHL, Bertelsen G, Skredderstuen A, Havelin LI, Furnes O. Pain and function in eight hundred and fifty nine patients comparing shoulder hemiprostheses, resurfacing prostheses, reversed total and conventional total prostheses. Int Orthop 2013; 37: 59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rasmussen JV, Polk A, Brorson S, Sørensen AK, Olsen BS. Patient-reported outcome and risk of revision after shoulder replacement for osteoarthritis 1,209 cases from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry, 2006–2010. Acta Orthopaedica 2014; 85: 117–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gartsman GM, Roddey TS, Hammerman SM. Shoulder arthroplasty with or without resurfacing of the glenoid in patients who have osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82: 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Edwards TB, Kadakia NR, Boulahia A, et al. A comparison of hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: results of a multicenter study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2003; 12: 207–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Radnay CS, Setter KJ, Chambers L, et al. Total shoulder replacement compared with humeral head replacement for the treatment of primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007; 16: 396–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bryant D, Litchfield R, Sandow M, et al. A comparison of pain, strength, range of motion, and functional outcomes after hemiarthroplasty and total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with osteoarthritis of the shoulder. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 1947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandow MJ, David H, Bentall SJ. Hemiarthroplasty vs total shoulder replacement for rotator cuff intact osteoarthritis: how do they fare after a decade? J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013; 22: 877–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singh JA, Sperling J, Buchbinder R, McMaken K. Surgery for shoulder osteoarthritis: a Cochrane systematic review. J Rheumatol 2011; 38: 594–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Litchfield RB, McKee MD, Balyk R, et al. Cemented versus uncemented fixation of humeral components in total shoulder arthroplasty for osteoarthritis of the shoulder: a prospective, randomized, double-blind clinical trial – A JOINTs Canada Project. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011; 20: 529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh J, Sperling J, Cofield R. Revision surgery following total shoulder arthroplasty: analysis of 2588 shoulders over three decades (1976 to 2008). J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93B: 1513–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]