Abstract

Objective

To determine the influence of obesity on neonatal outcomes of pregnancies resulting from assisted reproductive technology.

Methods

Population-based retrospective cohort study of all non-anomalous, live births in Ohio from 2007 to 2011, comparing differences in the frequency of adverse neonatal outcomes of women who conceived with assisted reproductive technology versus spontaneously conceived pregnancies and stratified by obesity status. Primary outcome was a composite of neonatal morbidities defined as ≥1 of the following: neonatal death, Apgar score of <7 at 5 min, assisted ventilation, neonatal intensive care unit admission, or transport to a tertiary care facility.

Results

Rates of adverse neonatal outcomes were significantly higher for assisted reproductive technology pregnancies than spontaneously conceived neonates; non-obese 25% versus 8% and obese 27% versus 10%, p < 0.001. Assisted reproductive technology was associated with a similar increased risk for adverse outcomes in both obese (adjusted odds ratio (aOR): 1.33, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.11–1.59) and non-obese women (aOR: 1.34, 95% CI: 1.18–1.51) even after adjustment for coexisting risk factors. This increased risk was driven by higher preterm births in assisted reproductive technology pregnancies; obese (aOR: 1.06, 95% CI: 0.86–1.31) and non-obese (aOR: 1.15, 95% CI: 1.00–1.32).

Discussion

Assisted reproductive technology is associated with a higher risk of adverse neonatal outcomes. Obesity does not appear to adversely modify perinatal risks associated with assisted reproductive technology.

Keywords: Obesity, assisted reproductive technology, perinatal outcomes

Background

Obesity is a worldwide epidemic affecting more than one-third of US adults. It is associated with multiple medical co-morbidities including cardiovascular and diabetic conditions in addition to the reproductive challenges of menstrual irregularity, anovulation, and increased frequency of miscarriages.1,2 One in five pregnant women are obese and over 50% are overweight or obese.3 Obesity has been associated with an increased risk in pregnancy complications including but not limited to gestational diabetes mellitus, preeclampsia, cesarean delivery, prematurity, stillbirth, congenital anomalies, macrosomia, and postoperative complications.1,3

Obese women are at a higher risk for infertility secondary to impaired ovarian function and poorer oocyte quality, menstrual irregularities, and metabolic alterations.4,5 Assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) comprised 1.56% (n = 61,610) of all US live born infants in 2011.6 Of women who undergo ART, obese women more frequently require high levels of gonadotropins to achieve ovarian stimulation, experience longer periods of ovarian stimulation, and have higher cycle cancellation rates compared to non-obese women.4,5

While women who undergo ART are at higher risk for perinatal mortality, preterm delivery, congenital anomalies, multiple gestation, and low birth weight, there remains a paucity of literature focusing on pregnancy outcomes of obese women who undergo ART.7,8 With significant perinatal risks associated with both ART and obesity, the purpose of this study is to determine if the risks related to ART are influenced by obesity status. We hypothesize that obesity increases the risk for adverse perinatal outcomes above the background risk associated with ART.

Methods

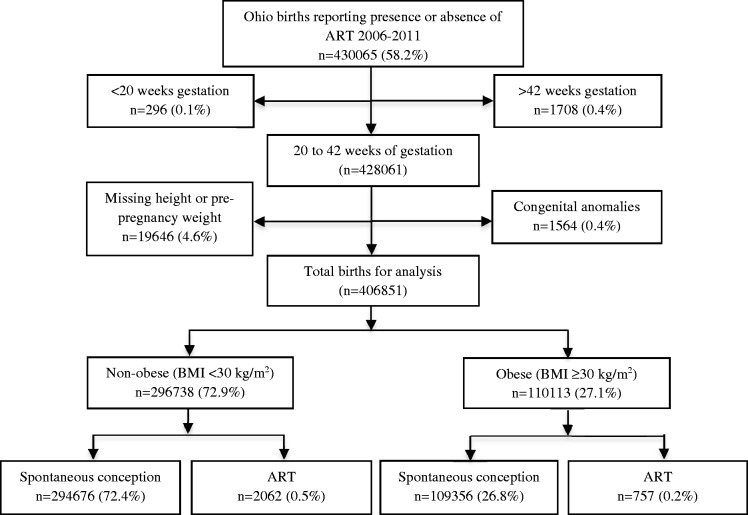

Study approval was obtained from the Ohio Department of Health and Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (2013-05 A) and review exemption from the University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH, USA. We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using the Ohio Department of Health’s birth certificate database from 2007 through 2011 to compare birth outcomes of women who conceived through ART and women with spontaneous conception. Our analysis of 430,065 births (58.2% of total Ohio births) included all births with recorded information for the presence or absence of ART. Congenital anomalies, patients who delivered at less than 20 or greater than 42 weeks of gestation, and women with missing maternal height or pre-pregnancy weight data were excluded from analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study population. BMI: body mass index; ART: assisted reproductive technology.

The primary exposure of interest for this study was ART. The referent group comprised births conceived spontaneously, coded as “no ART” in the birth record. The exposure group was stratified into obese and non-obese women, based on pre-pregnancy body mass index (BMI). Obesity was defined as a BMI of ≥30 kg/m2, and non-obese was categorized as women with BMI < 30 kg/m2. ART status was assigned as recorded on the birth certificate (as yes or no), and BMI was calculated from the recorded pre-pregnancy weight and height.

The primary outcome was a composite of neonatal adverse outcomes which was defined as one or more of the following indicators of poor newborn health: Apgar score of <7 at the 5 min evaluation, assisted ventilation >6 h duration, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, neonatal transport to a tertiary care facility, or neonatal death. This study concentrated on neonatal morbidities that occurred in the immediate 24 to 48 h after delivery as all later neonatal outcomes would not be recorded on the birth certificate. Data for neonatal death, defined as a neonatal demise <28 days of life, were obtained through a separate comprehensive death certificate database that was linked to the birth certificate dataset. Secondary perinatal outcomes were as reported on linked birth-death certificate record, including gestational diabetes and hypertension, maternal admission to the intensive care unit (ICU), eclampsia, and blood transfusion. Gestational hypertension is defined as hypertension and/or preeclampsia that is diagnosed during the current pregnancy.9

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software (STATA, release 10; Stata-Corp, College Station, TX). Demographic characteristics were compared between women who conceived using ART versus spontaneous conception using student’s t test for continuous variables and Chi square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. A stratified analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of obesity on adverse perinatal outcomes in women with and without ART. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to estimate the independent risk of ART on adverse neonatal outcome with adjustment for statistically significant and biologically plausible coexisting risk factors including maternal age, race, hypertension, diabetes, tobacco use, parity, multifetal gestation, mode of delivery, fetal growth restriction (FGR) defined as birthweight <10th percentile for week of gestation and preterm birth (PTB) (<37 weeks of gestation).10 Stepwise regression analyses of the composite adverse neonatal outcome were performed using multiple sequential models in order to determine the relative impact of each group of covariates on adjusted odds ratio (aOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) estimates in both non-obese and obese ART groups. Comparisons with a probability value <0.05 or 95% CI without inclusion of the null were considered statistically significant.

Results

Women who received ART represented 2819 (0.7%) of all births included in this analysis (n = 406,851) and were stratified into two groups based on obesity status. Of the births conceived with ART, 757 (0.2%) were to obese women and 2062 (0.5%) were non-obese. Spontaneously conceived pregnancies included 109,356 (26.8%) obese and 294,676 (72.4%) non-obese women. The dataset consisted of minimal missing information for primary outcomes of interest and covariates included in the adjusted analysis (<5%). Additionally, 0.24% of records were missing data for maternal age, 1.0% for NICU admission and ventilator support, and 0.3% for neonatal transport to a tertiary care center.

The demographic characteristic differences by ART group are displayed in Table 1. Spontaneously conceived pregnancies were more likely tobacco users and multiparous. Women who received ART were older and more likely to be Caucasian, to have a multifetal gestation (31% versus 3%, p < 0.001), and to experience PTB even with singleton pregnancies (12% versus 8%, p < 0.001) compared with the referent group. The rates of multifetal gestation were similar in both non-obese and obese ART groups (31.0% versus 31.3%, p = 0.48).

Table 1.

Maternal demographic and pregnancy characteristics.

| Characteristic | ART (n = 2381) | Spontaneous conception (n = 399,244) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 33 ± 6 | 27 ± 6 | <0.001 |

| Race and ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| Caucasian | 2094 (89) | 304113 (77) | |

| African American | 111 (5) | 64640 (16) | |

| Hispanic | 40 (2) | 16336 (4) | |

| Asian | 103 (4) | 10061 (3) | |

| Body mass index | 26 ± 7 | 26 ± 7 | 0.918 |

| Tobacco | 160 (7) | 98190 (25) | <0.001 |

| Pre-gestational diabetes | 27 (1) | 3253 (1) | 0.086 |

| Chronic hypertension | 65 (3) | 7619 (2) | 0.005 |

| Parity (IQR) | 1 (1,2) | 2 (1,3) | <0.001 |

| Multifetal gestation | 733 (31) | 9787 (3) | <0.001 |

| Preterm birtha | 1070 (37) | 43941 (10) | <0.001 |

| Singleton preterm birth | 202 (12) | 34400 (8) | <0.001 |

ART: assisted reproductive technology.

Dichotomous variables are presented as number (percent). Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range (IQR)) for non-normally distributed data and as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data.

Preterm birth including multiple gestation pregnancies.

Maternal complications and pregnancy outcome frequencies for spontaneous pregnancies and ART were compared and stratified by obesity status; summarized in Table 2. No difference in BMI was found between women who received ART to those who conceived spontaneously within each weight strata (non-obese spontaneous conception 23.0 ± 3.0 kg/m2 versus ART 23.1 ± 2.9 kg/m2, p = 0.40; obese spontaneous conception 35.3 ± 5.6 kg/m2 versus ART 35.1 ± 5.2 kg/m2, p = 0.61). All women who received ART were more likely to develop gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders, FGR, and to deliver preterm. ART pregnancies had increased frequencies of cesarean deliveries but obese women with ART had the highest rate of cesarean delivery compared to obese and non-obese spontaneous pregnancies (63% versus 41% and 26%, p < 0.001). Non-obese women who received ART had higher rates of maternal blood transfusions and admissions to the ICU compared to spontaneously conceived pregnancies.

Table 2.

Maternal and pregnancy outcomes.

| Obese |

Non-obese |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | ART (n = 641) | Spontaneous conception (n = 107,956) | p | ART (n = 1740) | Spontaneous conception (n = 291,288) | p |

| Gestational HTNa | 91 (14) | 8771 (8) | <0.001 | 120 (7) | 10273 (4) | <0.001 |

| Gestational DM | 110 (17) | 11358 (11) | <0.001 | 140 (8) | 10987 (4) | <0.001 |

| Eclampsia | 10 (2) | 1165 (1) | 0.070 | 22 (1) | 1527 (1) | <0.001 |

| Blood transfusion | 4 (<1) | 208 (<1) | 0.129 | 12 (1) | 597 (<1) | <0.001 |

| Admit to ICU | 1 (<1) | 133 (<1) | 0.547 | 7 (<1) | 278 (<1) | 0.002 |

| Preterm birth | 281 (37) | 12198 (11) | <0.001 | 730 (35) | 29124 (10) | <0.001 |

| FGR | 87 (12) | 9407 (9) | 0.006 | 331 (16) | 30794 (11) | <0.001 |

| Route of delivery | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Vaginal delivery | 210 (33) | 58959 (55) | 750 (43) | 198120 (68) | ||

| Cesarean delivery | 399 (63) | 44576 (41) | 856 (49) | 75126 (26) | ||

DM: diabetes mellitus; ICU: intensive care unit; FGR: fetal growth restriction; ART: assisted reproductive technology.

Dichotomous variables are presented as number (percent). Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range (IQR)) for non-normally distributed data and as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data.

Hypertension and/or preeclampsia diagnosed in the current pregnancy.

The primary outcome of composite adverse neonatal morbidity was compared between women who received ART and the referent, spontaneous conception group, stratified by obesity status (Table 3). Individual neonatal morbidity was highest for births to women who conceived with ART. The overall rate of composite neonatal morbidity was higher for ART groups, both non-obese (26%; 95% CI: 23.3–27.0%) and obese (27%; 95% CI: 23.8–30.1%) compared to the referent non-obese (8%; 95% CI: 8.1–8.3%; p < 0.001) and obese group (10%; 95% CI: 9.9–10.3%; p < .001).

Table 3.

Neonatal outcomes.

| Obese |

Non-obese |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | ART (n = 757) | Spontaneous conception (n = 109,356) | p | ART (n = 2062) | Spontaneous conception (n = 294,676) | p |

| Gestational age | 36 ± 4 | 38 ± 2 | <0.001 | 37 ± 4 | 39 ± 2 | <0.001 |

| Birth weight (g) | 2863 ± 899 | 3317 ± 661 | <0.001 | 2802 ± 849 | 3249 ± 605 | <0.001 |

| Mechanical ventilation >6 h | 36 (5) | 943 (1) | <0.001 | 113 (6) | 2116 (1) | <0.001 |

| NICU admission | 175 (23) | 8225 (8) | <0.001 | 435 (22) | 18510 (6) | <0.001 |

| 5 min Apgar < 7 | 40 (5) | 3259 (3) | 0.001 | 95 (5) | 6235 (2) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal transport | 66 (9) | 3293 (3) | <0.001 | 224 (11) | 7395 (3) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal death | 24 (3) | 565 (1) | <0.001 | 37 (2) | 1024 (<1) | <0.001 |

| Neonatal composite morbiditya | 203 (27) | 11044 (10) | <0.001 | 517 (26) | 24270 (8) | <0.001 |

NICU: neonatal intensive care unit; ART: assisted reproductive technology.

Dichotomous variables are presented as number (percent). Continuous variables are presented as median (interquartile range (IQR)) for non-normally distributed data and as mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data.

Composite morbidity defined as ≥1 of the following: NICU admission, Apgar score of <7 at 5 min, assisted ventilation for >6 h, neonatal death, or neonatal transport to a tertiary care facility.

Births following ART had significantly higher aOR for composite neonatal morbidity for both obese and non-obese pregnancies (see Table 4). The risk of adverse neonatal outcome was increased similarly by 34% in non-obese and 33% in obese women who underwent ART, aOR 1.34 (95% CI: 1.18–1.51) and 1.33 (95% CI: 1.11–1.59), despite adjustment for age, race, multifetal gestation, tobacco use, parity, diabetes, hypertension, FGR, and route of delivery. All of the included covariates had a statistically significant contribution within the regression model with p ≤ 0.001 except diabetes, hypertension, and FGR in obese women and FGR in non-obese women with ART. The difference in risk of composite neonatal morbidity with ART did not differ significantly when compared between the obese and non-obese ART groups, p = 0.435.

Table 4.

Logistic regression analysis of composite adverse neonatal outcome.

| Obese | Non-obese | |

|---|---|---|

| Model: Covariates | aOR (95% CI) | aOR (95% CI) |

| Model I: Age only | 3.06 (2.62–3.58) | 3.74 (3.37–4.14) |

| Model II: Model I + demographic factors | 3.25 (2.79–3.80) | 3.95 (3.56–4.38) |

| Model III: Model II + prenatal and pregnancy factors | 1.37 (1.15–1.63) | 1.40 (1.24–1.58) |

| Model IV: Model III + pregnancy complications and delivery factors | 1.33 (1.11–1.59) | 1.34 (1.18–1.51) |

| Model V: Model IV + PTB | 1.06 (0.86–1.31) | 1.15 (1.00–1.32) |

PTB: preterm birth; aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval.

Covariates included in each model: demographic factors = maternal race, tobacco use; prenatal and pregnancy factors = parity, multiple gestation; pregnancy complications and delivery factors = route of delivery, pre- and gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorder, fetal growth restriction.

Gestational age at delivery and multifetal gestation were the most influential factors contributing to the risk of adverse neonatal outcome associated with ART. The fully adjusted risk for composite adverse neonatal outcome became non-significant for women who conceived with ART after the addition of PTB to the multivariate logistic regression model; aOR: 1.06 (95% CI: 0.86–1.31) obese and aOR: 1.15 (95% CI: 1.00–1.32) non-obese women.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that obese women who conceive with ART have an increased risk of adverse perinatal outcomes similar to non-obese ART pregnancies. The results support the null hypothesis as the degree of adverse neonatal outcomes attributable to ART does not appear to be altered by the presence of obesity, despite the higher frequency of gestational co-morbidities observed in obese women. The main influence on adverse neonatal outcome risk with ART, regardless of obesity status, appears to be related primarily to the higher frequency of PTB in women undergoing ART.

In previous studies, women who received ART were more likely to be Caucasian, older, develop gestational hypertension and diabetes, deliver preterm, and via cesarean method.7,11–13 A large population study from Florida compared PTB rates between classifications of BMI categories in only women who had assisted conception and found the highest risk for early PTB in underweight women with no difference between BMI categories for late PTB.7 Our study is consistent in that obesity does not modify the risks for PTB in women who achieve pregnancy after ART. However, our study is unique because we quantify the risk attributable to ART by comparison to a non-ART referent group and then further analyze the influence of obesity to both ART and non-ART groups. The frequencies of gestational hypertension and diabetes were higher in ART pregnancies, with rates twice as high in the obese ART group compared to the non-obese ART group.

The major strength of this study is that it addresses two important areas in reproductive health; ART and obesity. This study compared ART perinatal risks to spontaneously conceived pregnancies and stratified the analysis by obesity status, which has its own independent pregnancy risks. Previous studies that have addressed the risks of obesity with ART have focused on implantation, live birth rates, spontaneous miscarriages, effects of weight loss, and factors related to the ART process.13–15 Our study aimed to identify pregnancy and neonatal risks of ART and the effect of obesity on these risks as maternal and neonatal health are important outcomes of interest for all women. The large sample size allowed for comparison of our primary outcome by assisted conception and stratification by obesity status. The inclusion of pregnancies within Ohio over a five-year period represents a population-based sample including various levels of obstetric acuity, different fertility and obstetric practice styles, and wide demographic diversity.

There are several limitations to this study most inherently to vital statistics research: quality data collection and entry, variable content available for analysis, and ascertainment bias of various outcomes. The demographic and outcome variables chosen for this study are common components described in the neonatal and maternal prenatal and hospital admission record, therefore, more likely representing higher quality and consistency between the chart and birth certificate.16 The components of the primary composite outcome have minimal missing data in the dataset and are clearly defined, expecting greater coding and entry accuracy. Analyzing the neonatal morbidities as a composite helps minimize under-reporting of individual outcomes and also represents morbidities with significant impact. ART and obesity have been associated with an increased risk for congenital anomalies which we have excluded in this study, under-representing complications that may occur more frequently in these populations. Long-term childhood outcomes or perinatal outcomes specific to particular ART techniques and cycle data cannot be differentiated from birth certificate data.

In Ohio vital statistics, ART is defined as “Assisted reproductive technology (e.g. in vitro fertilization, gamete intrafallopian transfer) - if yes check box” which represents a more heterogeneous group of women with potential confounders that cannot be accounted for in this study but can be generalized to all women who receive fertility assistance.9 The documented prevalence of ART in our Ohio birth cohort (0.7%) is lower than the reported national prevalence (1.56%).6 Excluding women who had ART but had missing data on the birth record from this analysis likely resulted in a smaller sample size in the exposure group. Lynch et al.18 studied birth certificates as a means of identifying births from assisted conception. We suspect differential under-reporting (i.e. missing data) of both the presence and absence of ART exposure in Ohio birth certificates, influencing the calculated population prevalence, but those coded as ART and those coded with no ART are likely accurately reported.17 They reported high specificity between maternal and birth certificate reporting of infertility treatment.18 The most common error documentation was the type of fertility drug used, which was not included in our study. Roohan et al.19described 80% sensitivity and 100% specificity of ART reporting in New York birth certificates in comparison to medical records. Therefore, despite the smaller exposure group than would be representative of the true population we suspect our risk estimates are accurate in effect size but may have wider confidence intervals than if measured in prospectively collected data.

ART is significantly associated with adverse neonatal outcomes including neonatal death and NICU admission which has been reported in the literature, but these associations appear to be mostly explained by increased rates of PTB and our study suggests that obesity alone does not alter these adverse perinatal outcomes.11,20 Prior reports have acknowledged higher rates of elective cesarean deliveries and induced labor in ART pregnancies, which can contribute to higher rates of PTB over and above the independent influence of ART on PTB risk.11,20 It is difficult to achieve significant numbers in prospective trials of cohorts of obese women undergoing ART and these are currently lacking in the literature. As the proportions of obese and ART populations in obstetrics increase, prospective analysis of outcomes will be essential as the benefits of delaying pregnancy for weight loss versus the challenges of advancing age with fertility and perinatal outcomes are a difficult balance and do not appear to improve outcome. Future studies to characterize the role of weight gain and inflammatory markers with adverse outcomes in this population are warranted to further understand the effects on fetal programming and health. This study provides important information to provide informed counseling to obese mothers who desire assisted conception and to educate clinicians who provide preconception and perinatal care to this growing group of high-risk women.

Acknowledgements

All authors of this manuscript actively participated and fulfill the conditions of authorship as outlined in the author instructions for Obstetric Medicine.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. DeFranco received research funding from the Perinatal Institute, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio; March of Dimes Grant 22-FY14-470.

Ethical approval

Ohio Department of Health and Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (2013-05 A) and review exemption from the University of Cincinnati Office of Research Integrity Institutional Review Board.

Guarantor

AMV

Contributorship

AV was involved in every aspect of the article submission including but not limited to the conception and design of the project, gathered and analyzed the data, drafted and revised the article submitted. EH was involved in data organization and design of the project as well as revising the article submitted. ED was intimately involved in the project design and served as a mentor in the data analysis and critical revisions of the article submitted.

References

- 1.Kumbak B, Oral E, Bukulmez O. Female obesity and assisted reproductive technologies. Semin Reprod Med 2012; 30: 507–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of obesity in the United States, 2009–2010. NCHS Data Brief 2012; 82: 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG committee opinion no. 549: obesity in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013; 121: 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bellver J, Busso C, Pellicer A, et al. Obesity and assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Reprod Biomed Online 2006; 12: 562–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pasquali R, Patton L, Gambineri A. Obesity and infertility. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2007; 14: 482–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.CDC, American Society for Reproductive Medicine, Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies. 2011 assisted reproductive technology national summary report, www.cdc.gov/ART/ (2013, accessed 27 January 2014).

- 7.Sauber-Schatz EK, Sappenfield W, Grigorescu V, et al. Obesity, assisted reproductive technology, and early preterm birth—Florida, 2004–2006. Am J Epidemiol 2012; 176: 886–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen VM, Wilson RD, Cheung A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technology. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2006; 28: 220–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Center for Health Statistics. Guide to completing the facility worksheets for the certificate of live birth and report of fetal death (2003 version). Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vital_certificate_revisions.htm (2012, accessed 1 December 2015).

- 10.Alexander GR, Himes JH, Kaufman RB, et al. A United States national reference for fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 1996; 87(2): 163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmerhorst FM, Perquin DA, Donker D, et al. Perinatal outcome of singletons and twins after assisted conception: a systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ 2004; 328: 261–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schieve LA, Ferre C, Peterson HB, et al. Perinatal outcome among singleton infants conceived through assisted reproductive technology in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103(6): 1144–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dokras A, Baredziak L, Blaine J, et al. Obstetric outcomes after in vitro fertilization in obese and morbidly obese women. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 108(1): 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moragianni VA, Jones SM, Ryley DA. The effect of body mass index on the outcomes of first assisted reproductive technology cycles. Fertil Steril 2012; 98(1): 102–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maheshwari A, Stofberg L, Bhattacharya S. Effect of overweight and obesity on assisted reproductive technology—a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 2007; 13: 433–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichman NE, Schwartz-Soicher O. Accuracy of birth certificate data by risk factors and outcomes: analysis of data from New Jersey. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007; 197: 32.e1–32.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thoma ME, Boulet S, Martin JA, et al. Births resulting from assisted reproductive technology: comparing birth certificate and National ART Surveillance System Data, 2011. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2014; 63: 1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lynch CD, Louis GM, Lahti MC, et al. The birth certificate as an efficient means of identifying children conceived with the help of infertility treatment. Am J Epidemiol 2011; 174: 211–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roohan PJ, Josberger RE, Acar J, et al. Validation of birth certificate data in New York State. J Community Health 2003; 28: 335–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson RA, Gibson KA, Wu YW, et al. Perinatal outcomes in singletons following in vitro fertilization: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103(3): 551–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]