Abstract

Background and Purpose

Ceftriaxone is a β‐lactam antibiotic and glutamate transporter activator that reduces the reinforcing effects of psychostimulants. Ceftriaxone also reduces locomotor activation following acute psychostimulant exposure, suggesting that alterations in dopamine transmission in the nucleus accumbens contribute to its mechanism of action. In the present studies we tested the hypothesis that pretreatment with ceftriaxone disrupts acute cocaine‐evoked dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens.

Experimental Approach

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats were pretreated with saline or ceftriaxone (200 mg kg−1, i.p. × 10 days) and then challenged with cocaine (15 mg kg−1, i.p.). Motor activity, dopamine efflux (via in vivo microdialysis) and protein levels of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), the dopamine transporter and organic cation transporter as well as α‐synuclein, Akt and GSK3β were analysed in the nucleus accumbens.

Key Results

Ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats challenged with cocaine displayed reduced locomotor activity and accumbal dopamine efflux compared with saline‐pretreated controls challenged with cocaine. The reduction in cocaine‐evoked dopamine levels was not counteracted by excitatory amino acid transporter 2 blockade in the nucleus accumbens. Pretreatment with ceftriaxone increased Akt/GSK3β signalling in the nucleus accumbens and reduced levels of dopamine transporter, TH and phosphorylated α‐synuclein, indicating that ceftriaxone affects numerous proteins involved in dopaminergic transmission.

Conclusions and Implications

These results are the first evidence that ceftriaxone affects cocaine‐evoked dopaminergic transmission, in addition to its well‐described effects on glutamate, and suggest that its ability to attenuate cocaine‐induced behaviours, such as psychomotor activity, is due in part to reduced dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens.

Abbreviations

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DHK

dihydrokainic acid

- EAAT2

excitatory amino acid transporter 2

- GSK3

glycogen synthase kinase 3

- OCT3

organic cation transporter 3

Tables of Links

These Tables list key protein targets and ligands in this article which are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY (Pawson et al., 2014) and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013/14 (a,b Alexander et al., 2013a,2013b).

Introduction

The nucleus accumbens is a locus of converging glutamatergic afferents from the amygdala, ventral hippocampus and prefrontal cortex and of dopaminergic afferents from the midbrain (Sesack and Grace, 2010). This anatomical organization enables the nucleus accumbens to integrate affective and motivational signals produced by salient stimuli to initiate a proper motor response (Wise, 2004; Stuber et al., 2008). The behavioural effects of psychomotor stimulant drugs are highly dependent on dopamine, glutamate and dopamine–glutamate interactions in the nucleus accumbens (Sesack et al., 2003; Kalivas et al., 2009). Dopamine negatively regulates the expression of astrocytic glutamate transporters in the striatum, while excitatory glutamatergic activity locally controls dopamine release in the accumbens (Attarian and Amalric, 1997; Vezina and Kim, 1999; Brito et al., 2009; Massie et al., 2010). Dopamine depletion abolishes the enhanced locomotion produced by accumbal glutamate receptor activation (Meeker et al., 1998). Thus, dopamine and glutamate interact to modulate one another's release and postsynaptic modulation of accumbal output neurons.

In addition to its well‐established antibacterial effects, the β‐lactam antibiotic ceftriaxone increases cellular glutamate uptake in the mammalian brain by activating excitatory amino acid transporter 2 (EAAT2) (Rothstein et al., 2005). EAAT2 is predominantly an astrocytic transporter responsible for clearing the majority of extracellular glutamate (Rothstein et al., 1995; Mitani and Tanaka, 2003). Repeated ceftriaxone treatment increases EAAT2 transporter expression and reduces extracellular glutamate levels in the nucleus accumbens of rats (Rasmussen et al., 2011). Repeated ceftriaxone treatment also attenuates the acute motor responses to amphetamine in rats (Rasmussen et al., 2011), inhibits the induction of behavioural sensitization in rats and mice (Sondheimer and Knackstedt, 2011; Tallarida et al., 2013) and diminishes cocaine self‐administration (Sari et al., 2009; Knackstedt et al., 2010; Ward et al., 2011; Trantham‐Davidson et al., 2012). Because both extracellular glutamate and dopamine regulate these behaviours, ceftriaxone treatment may alter dopaminergic as well as glutamatergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens. In support of this, ceftriaxone attenuates the acute motor‐stimulant effects of caffeine (Sondheimer and Knackstedt, 2011), which only requires increased dopamine signalling for this behavioural effect. Furthermore, ceftriaxone has been shown to be neuroprotective of dopaminergic neurons and dopamine‐regulated behavioural activity in rodent models of Parkinson's disease. However, how ceftriaxone mediates these therapeutic effects is still unclear (Leung et al., 2012; Bisht et al., 2014; Chotibut et al., 2014; Kelsey and Neville, 2014).

With regard to the neuroprotective effects of ceftriaxone in Parkinson's disease models, a recent study has demonstrated that ceftriaxone binds to α‐synuclein (Ruzza et al., 2014), which is an important regulator of dopaminergic transmission that interacts with the dopamine transporter (DAT) and TH, the rate‐limiting enzyme in dopamine synthesis (Abeliovich et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2001; Perez et al., 2002; Yu et al., 2004). α‐synuclein levels are elevated in midbrain dopamine neurons and in the striatum of chronic cocaine abusers, and the serum concentrations of α‐synuclein in cocaine‐dependent individuals are correlated with the intensity and frequency of cocaine craving. (Mash et al., 2003; Qin et al., 2005; Mash et al., 2008). α‐Synuclein expression is also increased in psychostimulant‐treated rodents, and overexpression of α‐synuclein in the nucleus accumbens induces an increase in locomotor activity and cocaine self‐administration, whereas inhibition of α‐synuclein in the nucleus accumbens reverses these effects (Brenz Verca et al., 2003; Boyer and Dreyer, 2007). In addition, rats that do not extinguish cocaine place preference have enhanced α‐synuclein expression when compared with rats that extinguished cocaine‐induced place preference (del Castillo et al., 2009). These data suggest a role for α‐synuclein in the neuropharmacological effects of psychostimulants and indicate that ceftriaxone may modulate dopaminergic activity and cocaine‐induced behavioural effects through interactions with α‐synuclein.

The present study investigated the effects of ceftriaxone pretreatment on cocaine‐induced dopaminergic neurotransmission and on protein levels of the principal regulatory components of dopaminergic neurotransmission in the rat nucleus accumbens, including α‐synuclein.

Methods

Animals

Seventy‐two male Sprague–Dawley rats (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN, USA; 250–275 g at start of experiments) were maintained on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 0700 h), and provided food and water ad libitum. At the end of each experiment, rats were killed by exposure to CO2 until unconscious (10–15 s) and decapitated. All studies are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010). Animal use procedures were conducted in strict accordance with the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (8th edition, 2011) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Temple University.

Effects of ceftriaxone pretreatment on acute cocaine‐induced hyperactivity

Thirty‐two rats were administered ceftriaxone (200 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Chicago, IL, USA) or saline once daily for 10 days (Tallarida et al., 2013). Twenty‐four hours following the last injection of saline or ceftriaxone, behavioural activity was evaluated following the administration of saline (1 mL kg−1, i.p.) or cocaine (15 mg kg−1, i.p.) (n = 8/group; saline–saline, ceftriaxone–saline, saline–cocaine and ceftriaxone–cocaine) in automated monitors containing 16 infrared light emitters and sensors mounted on a frame within which a standard plastic animal cage was positioned (45 × 20 × 20 cm; AccuScan Instruments, Inc, Columbus, OH, USA). The number of photocell beam breaks was recorded throughout a session (60 min post‐injection) by a Digiscan DMicro software system (AccuScan Instruments). Activity was divided into ambulation, defined as the number of consecutive beam breaks, and stereotypy, defined by the number of repetitive breaks of the same beam (Sanberg et al., 1987).

Effects of ceftriaxone pretreatment on cocaine‐induced changes in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens

Rats underwent surgery to implant chronic indwelling cannulae targeting the nucleus accumbens for later insertion of a microdialysis probe, as described previously (Barr et al., 2014). Twelve rats were anaesthetized with a mixture of ketamine hydrochloride (80 mg kg−1, i.p.) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1, i.p.) and placed within a small mammal stereotaxic frame (Kopf, Tujunga, CA, USA). Sterilized stainless steel guide cannulae (21 gauge, Plastic One, Roanoke, VA, USA) were implanted using stereotaxic coordinates of (in mm): +1·4 anterior and 1·0 lateral to bregma, and 5·8 ventral from dura for the nucleus accumbens, based on Paxinos and Watson (2009). Dummy cannulae that extended 2 mm beyond the tip of the microdialysis guide cannula were inserted immediately after surgery. Following surgery, rats were housed individually and allowed to recover for 2 days. Ceftriaxone (200 mg kg−1 day−1, i.p. n = 6) or saline (n = 6) was administered once daily for 10 days. Microdialysis was conducted in freely moving rats, 24 h following the last administration of ceftriaxone. The dummy cannulae were removed from the guide cannulae, and a laboratory‐made concentric microdialysis probe (2 mm exposed membrane length) was inserted into the guide cannula. A two‐channel liquid swivel (Instech Lab. Inc., Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA) connected to a microinfusion pump (CMA/102) guided the inlet and outlet tubing of the probe. Artificial CSF (containing 147 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 1.4 mM Na2HPO4, 2.1 mM MgCl2 and 1.6 mM CaCl2, pH 7.4) was continuously perfused through the probe at a rate of 0.5 μL min−1. Dialysate collection began 4–6 h following probe insertion at 15 min intervals (at 1300–1400 h). Following collection of four baseline samples, cocaine (15 mg kg−1, i.p.) was administered, and dialysates were then collected for an additional 90 min. Following the experiments, rats were killed. Brains were histologically evaluated for probe placement and dialysates subsequently analysed for dopamine using HPLC with electrochemical detection.

Effects of a glutamate transporter inhibitor dihydrokainate on the ability of ceftriaxone to reduce cocaine‐induced extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens

Repeated ceftriaxone treatment reduces extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens, and the effect is prevented by the astroglial EAAT2 inhibitor dihydrokainic acid (DHK) (Sari et al., 2009; Rasmussen et al., 2011). Therefore, we conducted an additional experiment with DHK to determine if glutamate transporter activation was necessary for ceftriaxone to reduce cocaine‐induced extracellular dopamine. Eight rats underwent microdialysis experiments 24 h after the last ceftriaxone or saline (n = 4 per group) injection using the general procedures outlined for Experiment 2. Experiments were initiated following the collection of three baseline samples. To assess the effects of ceftriaxone on extracellular concentrations of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens following blockade of glutamate transporters, perfusion with aCSF was changed to perfusion with aCSF containing DHK (1 mM, Tocris Bioscience, Cat No 0111; Rasmussen et al., 2011) via the microdialysis probe for the remainder of the experiment. After 45 min (three additional samples), cocaine was administered at a dose of 15 mg kg−1, i.p., and dialysates collected for another 45 min. Following the experiments, rats were killed. Brains were histologically evaluated for probe placement and dialysates subsequently analysed for dopamine using high‐performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection.

Histological analysis

Brains were removed, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and sectioned at 60 µm on a Vibratome (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA). Sections were examined under a light microscope to determine probe placement for each animal. Only data from rats with correct placements in the nucleus accumbens were included in the analyses.

Dopamine quantification by HPLC

Dopamine was quantified from dialysates as described previously (Barr et al., 2014). The mobile phase (containing in 500 mL: 340 mg EDTA, 250 mg sodium octane sulfonate, 4.7 g NaH2PO4, 250 μL trimethylamine and 85 mL methanol, pH 5.75; all obtained from Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) was pumped through a UniJet 3 µm C18 microbore column (Bioanalytical Systems; West Lafayette, IN, USA) under nitrogen gas pressure (1.4 x 107 Pa). Dialysates were injected onto the chromatographic system using a rheodyne injector via a 5 μL loop (Bioanalytical Systems). Following separation by the column, dopamine was detected by a glassy carbon electrode (Bioanalytical Systems), which was maintained at +0.5 V with respect to an Ag /AgCl2 reference electrode using an LC‐4C potentiostat (Bioanalytical Systems). The voltage output was recorded by Clarity v2.4 Chromatography Station for Windows (DataApex, Prague, Czech Republic). Dopamine peaks were identified by comparison with a dopamine standard (9.2 pg 5 μL−1 dopamine). The 2:1 signal‐to‐noise detection limit for dopamine using this system was 0.026±0.009 pg.

Effects of ceftriaxone pretreatment on levels of dopaminergic signalling‐related proteins in the nucleus accumbens

A separate cohort of 20 rats was administered saline (n = 10, 1 mL kg−1, i.p.) or ceftriaxone (n = 10, 200 mg kg−1, i.p.) once daily for 10 days, killed 24 h after the last injection (coinciding with time of activity and microdialysis measures), and the nucleus accumbens was dissected rapidly on ice. Samples were prepared by homogenizing tissue from individual animals in boiling 1% (g 100 mL−1) SDS with 1 mM NaF and 1 mM Na3VO4 as phosphatase inhibitors. Samples were then boiled for 5 min and stored at −80°C.

For Western immunoblotting, equal amounts of protein (20 µg, determined using a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 2000 spectrometer) from all samples were loaded on 7.5% or 4–20% mini‐Protean TGX gels (Bio Rad) for separation and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. After being blocked for 60 min at room temperature, membranes were incubated either overnight at 4°C with anti‐DAT (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc‐1433), organic cation transporter 3 (OCT3) (1:1000; OCT31‐A; α Diagnostics International, 1:1000), phospho‐α‐synuclein (Ser129, 1:500, EMD Millipore Corp. AB9850), α‐synuclein (1:500, cell signalling #4179), phospho‐Akt‐Ser 473 (1:1000 cell signalling, #4051), phospho‐ GSK3β‐S9 (1:1000 #9323), Akt (1:2000 cell signalling, #9272), GSK3β (1:1000, cell signalling, #9832) or for 90 min at room temperature with rabbit anti‐TH (1:1000, cell signalling, #2792). After being washed, membranes were further incubated with appropriate IRDye 800 or 680‐conjugated IgG second antibody (Li‐Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA; 1:20 000) for 1 h at room temperature. Control for protein loading was achieved by using primary antibodies to β‐tubulin (1:800 000; cell signalling, #4466). Proteins were detected using the Odyssey infrared imaging system (LI‐COR Biosciences). Ratios of densities of phosphorylated proteins to β‐tubulin levels and total specific proteins to β‐tubulin were calculated.

Statistical analyses

All statistical tests were conducted with Graphpad Prism 5 (La Jolla, CA) with the α level set at 0.05. Locomotor time‐course data were presented in 10 min intervals and analysed by two‐way (pretreatment × time) repeated measures anova followed by a Bonferroni's post test. Cumulative locomotor data were analysed by one‐way anova followed by a Bonferroni's post test. Dopamine levels from microdialysis experiments were expressed as % change from baseline levels. Two‐way repeated‐measures anova (pretreatment × time) was used to compare dopamine levels across time between saline‐administered and ceftriaxone‐administered rats. Significant main effects were followed by Bonferroni's post test. Significant main effects of time were followed by separate one‐way repeated‐measures anova for each group, with significant effects across time identified by post hoc Holm–Sidak tests for multiple comparisons with a single control, where the last baseline sample served as the control. Quantification of immunoblots was analysed by Student's t‐test.

Results

Ceftriaxone pretreatment reduced acute cocaine‐induced hyperactivity

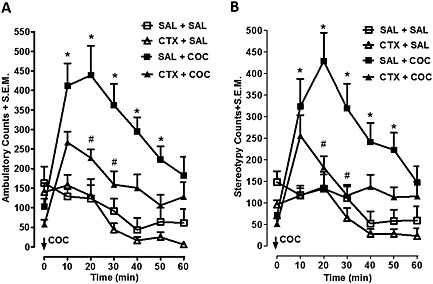

Time course of ambulatory activity counts over 60 min is shown in Figure 1A. Two‐way repeated‐measures anova of the ambulatory activity showed main effects of treatment (F 3, 196 = 52.99; P < 0.001) and time (F 6, 196 = 11.86; P < 0.001) and a significant interaction (F 18, 196 = 3.353; P < 0.001). Bonferroni post tests indicated that cocaine increased ambulatory activity 10–50 min post‐injection in saline‐pretreated controls (P < 0.001). Ceftriaxone decreased ambulatory activity compared with saline controls at 20 and 30 min post‐cocaine injection (P < 0.01). Stereotypic activity recorded following cocaine injection is shown in Figure 2 for rats pretreated with ceftriaxone or saline. Two‐way repeated‐measures anova demonstrated significant differences between treatment groups (interaction: F 18, 196 = 3.135, P < 0.0001; time: F 6, 196 = 10.73, P < 0.0001; treatment: F 3, 196 = 39.93, P < 0.0001).). Bonferroni post tests indicated that cocaine increased stereotype activity 10–50 min post‐injection in saline‐pretreated controls (P < 0.001). Bonferroni post hoc analysis revealed that ceftriaxone pretreatment produced a significant reduction in sterotype behaviours compared with saline‐injected controls at 20 and 30 min post‐cocaine injection (P < 0.01).

Figure 1.

Time course of acute cocaine‐induced behaviour following ceftriaxone pretreatment. (A) The time course of ambulatory activity is shown for mice injected with saline or ceftriaxone (200 mg kg−1 for 10 days) before cocaine (15 mg kg−1). Cocaine increased ambulatory activity in saline pretreated controls from 10–50 min post‐injection (P < 0.05). Pretreatment with ceftriaxone significantly attenuated cocaine‐induced ambulation compared to saline‐injected controls (P < 0.05). (B) The time course of changes in stereotype activity is shown for rats pretreated with ceftriaxone or saline prior to cocaine (15 mg kg−1). Cocaine increased ambulatory activity in saline pretreated controls from 10 to 50 min post‐injection (P < 0.05). Ceftriaxone significantly reduced the number of stereotypy counts observed in cocaine‐injected rats (P < 0.05). Data points represent mean + SEM (n = 8 per group). * Significantly different from saline controls. # Significantly different from SAL + COC group. SAL = saline, COC = cocaine. CTX = ceftriaxone.

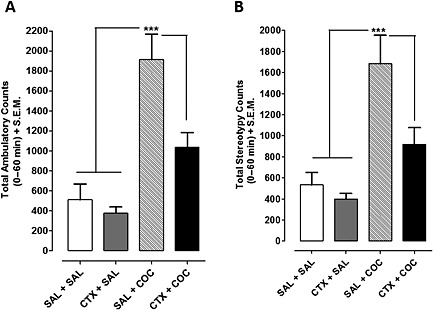

Figure 2.

Cumulative acute cocaine‐induced behavioural activity following ceftriaxone pretreatment. (A) Cumulative ambulatory activity for 60 min post‐cocaine is shown for rats pretreated with ceftriaxone or saline. (B) Stereotypy counts recorded for 60 min from rats pretreated with ceftriaxone or saline before cocaine (15 mg kg−1) injection are shown. Cocaine significantly increased ambulatory activity and stereotypy counts in saline‐pretreated rats compared with all other groups (P < 0.05). Data points represent mean + SEM (n = 8 per group). SAL = saleforeine, COC = cocaine. CTX = ceftriaxone.

Cumulative ambulatory activity counts over 60 min are shown in Figure 2A. One‐way anova of the ambulatory activity showed effects of treatment (F 3,31 = 17, P < 0.0001). Cocaine‐induced ambulatory activity in saline‐pretreated rats was significantly greater than all other groups (P < 0.05), whereas ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats administered cocaine showed ambulatory activity similar to saline controls (P > 0.05). Cumulative stereotype activity over 60 min is represented in Figure 2B. Pretreatment with ceftriaxone significantly reduced cocaine‐induced stereotype activity compared with saline‐pretreated controls (F 3, 31 = 11.57, P < 0.0001). Pretreatment with ceftriaxone alone had no effect on stereotypy following saline injections (P > 0.05). Therefore, 10 day pretreatment of ceftriaxone diminished acute cocaine‐induced ambulatory and stereotype activity.

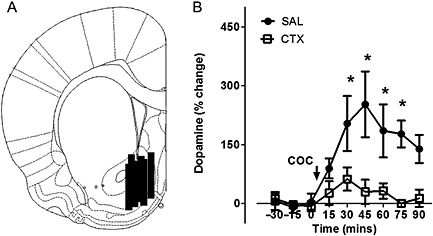

Ceftriaxone pretreatment reduced cocaine‐induced extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens

Baseline levels of dopamine for saline‐pretreated rats were 0.89 ± 0.8 pg 5 μL−1, and for ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats were 0.74 ± 0.7 pg 5 μL−1 (uncorrected for recovery). There was no statistical difference in baseline dopamine levels between groups (P > 0.05). Analysis of dopamine levels following cocaine administration (Figure 2A), showed a significant effect of time (F 9,121 = 8.53; P < 0.001), pretreatment (F 1,121 = 7.98; P = 0.016) and a significant interaction between pretreatment and time (F 9, 121 = 4.64; P < 0.001). Post hoc analysis revealed that the cocaine‐evoked increase in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats pretreated with saline was greater than ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats from 30 to 75 min post‐infusion (P < 0.05; Figure 2A). One‐way repeated‐measures ANOVA revealed an effect of cocaine over time for the saline‐pretreated rats (F 5,56 = 7.276; P < 0.001), apparent at 30 to 75 min post‐injection (Holm–Sidak; P < 0.05). No significant effect of cocaine over time was observed for the ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats (F 6,64 = 1.241; P = 0.293).

Post hoc examination of placement of microdialysis probes ensured that the 2 mm length of dialysis membrane sampled from the nucleus accumbens (Figure 2B) were similarly distributed in saline‐administered and ceftriaxone‐administered rats. One saline‐treated rat was removed from analysis due to missed probe placement. These data demonstrate that ceftriaxone pretreatment abolished acute cocaine‐evoked increase in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens.

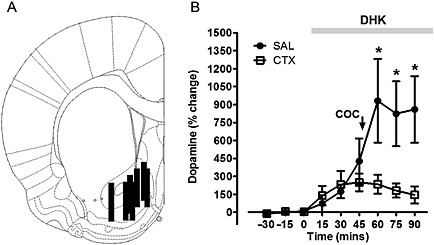

DHK did not counteract the ability of ceftriaxone to reduce cocaine‐induced extracellular dopamine levels in the nucleus accumbens

Baseline levels of dopamine for saline‐pretreated rats were 1.97 ± 0.68 pg 5 μL−1, and for ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats were 2.19 ± 0.69 pg 5 μL−1(uncorrected for recovery). There was no statistical difference in baseline dopamine levels between groups (P > 0.05). Analysis of dopamine levels, following perfusion of the glutamate transporter inhibitor DHK and cocaine administration (Figure 3A), showed a significant effect of time (F 8,61 = 11.80; P < 0.001), pretreatment (F 1,61 = 7.34; P = 0.042) and a significant interaction between pretreatment and time (F 8,61 = 5.29; P < 0.001). One‐way repeated‐measures ANOVA revealed an effect over time for the saline‐pretreated rats (F 2·26 = 6.698; P < 0.001), apparent at 15 to 75 min post‐infusion, and an effect over time was also observed for ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats (F 3·34 = 6.362; P < 0.001) at 15 to 60 min (Holm–Sidak; P < 0.05). Acute administration of cocaine evoked an increase in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of rats pretreated with saline that was greater than in ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats from 60 to 90 min post‐infusion (P < 0.05; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Pretreatment with ceftriaxone attenuated acute cocaine‐induced dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens. Effects of acute cocaine on extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of saline‐pretreated and ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats expressed as a percentage of baseline. (A) Representative coronal diagram of microdialysis probe membrane placements in saline and ceftriaxone pretreatment groups. Black bars represent the membrane of one or more probes. Figure adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2009), bregma −1.44 mm) (B) Ceftriaxone pretreatment restrained extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens following acute cocaine administration. *Significant difference between saline‐pretreated and ceftriaxone‐pretreated groups (P < 0.05). Data represent mean + SEM. (n = 5–6 per group).

Post hoc examination of placement of microdialysis probes ensured that the 2 mm length of dialysis membrane sampled from the nucleus accumbens (Figure 3B) were similarly distributed in saline‐administered and ceftriaxone‐administered rats. These data demonstrate that ceftriaxone pretreatment induced attenuation of acute cocaine‐evoked increase in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens was independent of glutamate transporter blockade.

Ceftriaxone reduced dopamine regulatory proteins and altered Akt/GSK3 signalling in the nucleus accumbens

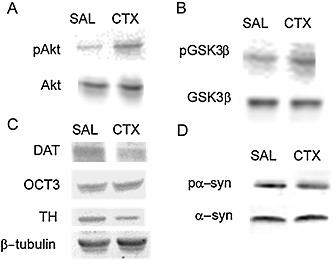

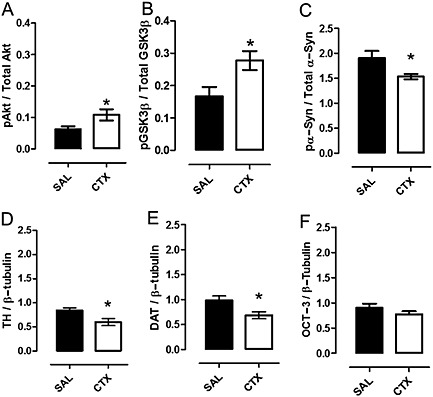

This experiment was conducted to examine whether ceftriaxone pretreatment alters the activity of proteins implicated in dopamine synthesis and clearance mechanisms. Significant increases in the phosphorylation of Akt‐Ser473 (t 11 = 2·35; P < 0·05) and GSK3β‐Ser9 (t16 = 2.7; P < 0.05) were found in the nucleus accumbens of rats pretreated with ceftriaxone as compared with the levels in rats that were pretreated with saline (Figures 4 and 5A and B). The levels of total Akt/tubulin, GSK3β/tubulin and α‐synuclein /tubulin did not differ between experimental groups (data not shown). Following ceftriaxone pretreatment, there was a significant decrease in phospho‐α‐synuclein (Figures 4D and 5C, t 11 = 2.65; P < 0.05), TH (Figures 4C and 5D; t18 = 2.644, P < 0.05) and DAT (Figure 4C, 5E; t16 = 2.626, P < 0.05). There was no significant effect of ceftriaxone on OCT3 levels (Figures 4C and 5 F). Therefore, chronic pretreatment with ceftriaxone alters cellular signalling pathways and proteins involved in both dopamine synthesis and clearance mechanisms. (Figure 6)

Figure 4.

Increased extracellular glutamate via blockade of EAAT2 does not prevent ceftriaxone‐induced attenuation of acute cocaine‐evoked dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens. Effects of acute cocaine on extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of saline‐pretreated and ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats expressed as a percentage of baseline. (A) Representative coronal diagram of microdialysis probe membrane placements in saline and ceftriaxone pretreatment groups. Black bars represent the membrane of one or more probes. Figure adapted from Paxinos and Watson (2009, bregma −1.44 mm) (B) Ceftriaxone pretreatment restrained extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens following acute cocaine administration in the presence of EAAT2 blockade with the selective inhibitor DHK (grey bar). *Significant difference between saline‐pretreated and ceftriaxone‐pretreated groups (P < 0·05). Data represent mean + SEM. (n = 4 per group).

Figure 5.

Representative immunoblots for dopamine signalling related proteins in the nucleus accumbens. Representative immunoblots for (A) phosphorylated Akt and total Akt (60 kD). (B) phosphorylated Ser9‐GSK3β and total GSK3β (46 kD). (C) DAT (70 kD), OCT3 (53 kD), TH (58 kD) and β‐tubulin (50 kD). (D) phosphorylated α‐synuclein and total α‐synuclein (18 kD).

Figure 6.

Pretreatment with ceftriaxone altered dopamine signalling related proteins in the nucleus accumbens. Ceftriaxone (200 mg kg−1, i.p., 10 days) reduced the phosphorylation of pAkt‐Ser473, pGSK3β‐Ser9 and α‐synuclein measured by Western blot analysis in rat nucleus accumbens as compared with saline. Bars represent the mean ± SEM (n = 7–10 per group) and are expressed as a ratio of pAkt: total Akt (A), pGSK3β: total GSK3β (B) or pα‐synuclein: total α‐synuclein (C). Protein expression of TH (D) and DAT (E) were significantly reduced in rats pretreated with ceftriaxone. (F) Pretreatment with ceftriaxone did not significantly alter levels of OCT3 in the nucleus accumbens.*Significant difference between saline and ceftriaxone groups (P < 0.05). Means±SEM are shown. (n = 10 per group).

Discussion and conclusions

The present study investigated the influence of the β‐lactam antibiotic ceftriaxone on dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens of rats treated with acute cocaine. Chronic pretreatment with ceftriaxone attenuated acute cocaine‐induced increases of both locomotor activity (ambulation and stereotypy) and extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. Augmented glutamate neurotransmission, through DHK‐mediated uptake blockade, increased extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens of both saline‐pretreated and ceftriaxone‐pretreated groups similar to previous studies (Segovia et al., 1997; Segovia and Mora, 2001). Additional administration of cocaine, in the presence of DHK, further increased extracellular dopamine in saline‐pretreated rats but did not further increase dopamine levels in ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats, suggesting that a glutamate uptake block did not restore the ability of cocaine to elicit an increase in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens.

Cocaine increases extracellular monoamine availability by blocking cellular uptake of dopamine. The capacity of acute cocaine to induce motor activity is dependent on the dopamine transporter (DAT; Shen et al., 2004; Hall et al., 2009). Reduced DAT expression in ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats may therefore underlie the reduced ability of cocaine to increase synaptic dopamine and therefore motor activity. The organic cation transporter‐3 (OCT3) is also capable of transporting dopamine, along with other monoamines, and is expressed in the nucleus accumbens (Gasser et al., 2009; Duan and Wang, 2010; Graf et al., 2013). Pretreatment with ceftriaxone did not alter OCT3 protein levels in the nucleus accumbens, and therefore, OCT3 could not account for the reduced cocaine‐evoked increases in extracellular dopamine observed in the ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats. In addition, a reduction of TH was also detected in ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats, suggesting a constrained pool of releasable dopamine. Although baseline levels of dopamine were not significantly different between rats treated with ceftriaxone and saline, average extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens is low (Owesson‐White et al., 2012), suggesting that induction of phasic dopamine release may be necessary to reveal potential ceftriaxone‐mediated alterations in dopamine signalling. Overall, it appears that the reduced behavioural and pharmacological effects of cocaine following chronic ceftriaxone treatment could be due to reduced substrate (DAT and dopamine stores) for cocaine to target within the nucleus accumbens.

The activation of Akt in astrocytes is promoted by ceftriaxone (Feng et al., 2014). In the present study, an increase in phosphorylation of Akt (activation) and GSK3β (inactivation) was found in the nucleus accumbens of ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats. Acute cocaine administration decreases Akt activity and increases GSK3β activity in the striatum and nucleus accumbens core (Kim et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2014), which regulates cocaine‐induced behavioural sensitization (Xu et al., 2009). Inhibitors of GSK3 can block cocaine‐induced motor activity and sensitization (Miller et al., 2009). The nucleus accumbens core is also more sensitive to psychostimulant‐induced and ceftriaxone‐induced alterations to EAAT2 expression and cocaine‐seeking behaviour (Fischer‐Smith et al., 2012; Fischer et al., 2013). Given that cocaine‐induced activation of GSK3β can be inhibited by both dopamine and glutamate receptor blockade (Miller et al., 2014), it is likely that ceftriaxone acts through the Akt‐GSK3 pathway to influence regulatory peptides of both dopamine (Garcia et al., 2005) and glutamate (Ji et al., 2013) that are important for ceftriaxone effects on cocaine‐induced behavioural activity and reward.

Ceftriaxone has recently been shown to bind to α‐synuclein, a potent regulator of dopaminergic transmission (Abeliovich et al., 2000; Guo et al., 2008; Ruzza et al., 2014). α‐synuclein interacts with TH as well as aromatic amino acid decarboxylase in the striatum (Perez et al., 2002; Tehranian et al., 2006) and also regulates cell surface expression of DAT (Kisos et al., 2014). Therefore, the interaction of ceftriaxone with α‐synuclein may directly influence multiple proteins involved in dopamine homeostasis. No change in protein levels of α‐synuclein was detected in ceftriaxone‐pretreated rats, although ceftriaxone did reduce phosphorylation of α‐synuclein. Phosphorylation of α‐synuclein reduces its inhibition of TH activity (Lou et al., 2010) and is associated with aggregation of α‐synuclein, which is also coupled with greater GSK3β activity (Yuan et al., 2015). Therefore, ceftriaxone, by inhibiting GSK3β and reducing α‐synuclein phosphorylation, may enable α‐synuclein to inhibit TH and promote DAT internalization. Further assessment of the role of the interaction between ceftriaxone and α‐synuclein in regulating dopamine synthesis and reuptake is required to resolve the functional consequences of these proteins on endogenous dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens. Importantly, while the present study examined cocaine‐evoked dopamine and protein measures in whole nucleus accumbens, the nucleus accumbens contains two sub‐regions; the core and shell, which have separate afferent and efferent projections (Brog et al., 1993). Cocaine has been shown to increase dopamine preferentially in the nucleus accumbens shell during cocaine self‐administration (Lecca et al., 2007). Therefore, differences in connectivity and dopamine responsivity indicate that these sub‐regions are differentially involved in dopamine‐regulated behaviours. Further study is required to determine sub‐regional differences in ceftriaxone effects on dopaminergic activity. It should also be mentioned that antibiotics containing a β‐lactam core have a strong metal chelating ability (Ji et al., 2005), and this effect (e.g. chelation of calcium ions) could result in reduced neurotransmission.

In conclusion, we provide initial evidence that ceftriaxone exerts effects on the dopamine system in addition to its effects on glutamate. Ceftriaxone reduced the locomotor‐activating and dopamine‐activating effects of cocaine through a mechanism that is not sensitive to a glutamate re‐uptake blocker and affected some of the principal regulatory components of dopamine transmission. Our findings indicate that ceftriaxone may produce its well‐documented inhibition of cocaine's behavioural effects through a mechanism involving reduced dopaminergic transmission in the nucleus accumbens.

Author contributions

J. L. B., B. A. R., C. S. T., J. L. S. and G. L. F. performed the research. S. M. R. and J. L. B. designed the research study. G. L. F. and E. M. U. contributed essential reagents and tools. J. L. B., G. L. F. and S. M. R. analysed the data. J. L. B., G. L. F., E. M. U. and S. M. R. wrote the paper.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIDA T32 DA007237, P30 DA013429, R21 DA030676 and R01 DA019921. We would like to thank Ms. Mary McCafferty for her valued assistance and the NIDA Drug Supply Programme for supplying cocaine hydrochloride for our studies.

Barr, J. L. , Rasmussen, B. A. , Tallarida, C. S. , Scholl, J. L. , Forster, G. L. , Unterwald, E. M. , and Rawls, S. M. (2015) Ceftriaxone attenuates acute cocaine‐evoked dopaminergic neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens of the rat. British Journal of Pharmacology, 172: 5414–5424. doi: 10.1111/bph.13330.

References

- Abeliovich A, Schmitz Y, Fariñas I, Choi‐Lundberg D, Ho WH, Castillo PE et al. (2000). Mice lacking alpha‐synuclein display functional deficits in the nigrostriatal dopamine system. Neuron 25: 239–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al. (2013a). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013: transporters. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1706–1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander SPH, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Spedding M et al. (2013b). The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2013: enzymes. Br J Pharmacol 170: 1797–1867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attarian S, Amalric M (1997). Microinfusion of the metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist 1S, 3R‐1‐aminocyclopentane‐1, 3‐dicarboxylic acid into the nucleus accumbens induces dopamine‐dependent locomotor activation in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 9: 809–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr JL, Forster GL, Unterwald EM (2014). Repeated cocaine enhances ventral hippocampal‐stimulated dopamine efflux in the nucleus accumbens and alters ventral hippocampal NMDA receptor subunit expression. J Neurochem 130: 583–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht R, Kaur B, Gupta H, Prakash A (2014). Ceftriaxone mediated rescue of nigral oxidative damage and motor deficits in MPTP model of Parkinson's disease in rats. Neurotoxicology 44: 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer F, Dreyer JL (2007). Alpha‐synuclein in the nucleus accumbens induces changes in cocaine behaviour in rats. Eur J Neurosci 26: 2764–2776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenz Verca MS, Bahi A, Boyer F, Wagner GC, Dreyer JL (2003). Distribution of alpha‐ and gamma‐synucleins in the adult rat brain and their modification by high‐dose cocaine treatment. Eur J Neurosci 18: 38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brito V, Rozanski VE, Beyer C, Küppers E (2009). Dopamine regulates the expression of the glutamate transporter GLT1 but not GLAST in developing striatal astrocytes. J Mol Neurosci 39: 372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brog JS, Salyapongse A, Deutch AY, Zahm DS (1993). The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the “accumbens” part of the rat ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro‐gold. J Comp Neurol 338: 255–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Castillo C, Morales L, Alguacil LF, Salas E, Garrido E, Alonso E et al. (2009). Proteomic analysis of the nucleus accumbens of rats with different vulnerability to cocaine addiction. Neuropharmacology 57: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chotibut T, Davis RW, Arnold JC, Frenchek Z, Gurwara S, Bondada V et al. (2014). Ceftriaxone increases glutamate uptake and reduces striatal tyrosine hydroxylase loss in 6‐OHDA Parkinson's model. Mol Neurobiol 49: 1282–1292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan H, Wang J (2010). Selective transport of monoamine neurotransmitters by human plasma membrane monoamine transporter and organic cation transporter 3. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 335: 743–753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng D, Wang W, Dong Y, Wu L, Huang J, Ma Y et al. (2014). Ceftriaxone alleviates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage by increasing excitatory amino acid transporter 2 expression via the PI3K/Akt/NF‐κB signaling pathway. Neuroscience 268: 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer KD, Houston AC, Rebec GV (2013). Role of the major glutamate transporter GLT1 in nucleus accumbens core versus shell in cue‐induced cocaine‐seeking behavior. J Neurosci 33: 9319–9327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer‐Smith KD, Houston AC, Rebec GV (2012). Differential effects of cocaine access and withdrawal on glutamate type 1 transporter expression in rat nucleus accumbens core and shell. Neuroscience 210: 333–339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia BG, Wei Y, Moron JA, Lin RZ, Javitch JA et al. (2005). Akt is essential for insulin modulation of amphetamine‐induced human dopamine transporter cell‐surface redistribution. Mol Pharmacol 68: 102–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser PJ, Orchinik M, Raju I, Lowry CA (2009). Distribution of organic cation transporter 3, a corticosterone‐sensitive monoamine transporter, in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 512: 529–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf EN, Wheeler RA, Baker DA, Ebben AL, Hill JE, McReynolds JR et al. (2013). Corticosterone acts in the nucleus accumbens to enhance dopamine signaling and potentiate reinstatement of cocaine seeking. J Neurosci 33: 11800–11810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo JT, Chen AQ, Kong Q, Zhu H, Ma CM, Qin C (2008). Inhibition of vesicular monoamine transporter‐2 activity in alpha‐synuclein stably transfected SH‐SY5Y cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol 28: 35–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall FS, Li XF, Randall‐Thompson J, Sora I, Murphy DL, Lesch KP et al. (2009). Cocaine‐conditioned locomotion in dopamine transporter, norepinephrine transporter and 5‐HT transporter knockout mice. Neuroscience 162: 870–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji HF, Shen L, Zhang HY (2005). Beta‐lactam antibiotics are multipotent agents to combat neurological diseases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 333: 661–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji YF, Zhou L, Xie YJ, Xu SM, Zhu J, Teng P et al. (2013). Upregulation of glutamate transporter GLT‐1 by mTOR‐Akt‐NF‐кB cascade in astrocytic oxygen‐glucose deprivation. Glia 61: 1959–1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Lalumiere RT, Knackstedt L, Shen H (2009). Glutamate transmission in addiction. Neuropharmacology 56: 169–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsey JE, Neville C (2014). The effects of the β‐lactam antibiotic, ceftriaxone, on forepaw stepping and L‐DOPA‐induced dyskinesia in a rodent model of Parkinson's disease. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 231: 2405–2415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG (2010). Animal research: reporting in vivo experiments: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1577–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim WY, Jang JK, Lee JW, Jang H, Kim JH (2013). Decrease of GSK3β phosphorylation in the rat nucleus accumbens core enhances cocaine‐induced hyper‐locomotor activity. J Neurochem 125: 642–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisos H, Ben‐Gedalya T, Sharon R (2014). The clathrin‐dependent localization of dopamine transporter to surface membranes is affected by α‐synuclein. J Mol Neurosci 52: 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knackstedt LA, Melendez RI, Kalivas PW (2010). Ceftriaxone restores glutamate homeostasis and prevents relapse to cocaine seeking. Biol Psychiatry 67: 81–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecca D, Cacciapaglia F, Valentini V, Acquas E, Di Chiara G (2007). Differential neurochemical and behavioral adaptation to cocaine after response contingent and noncontingent exposure in the rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 191: 653–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FJ, Liu F, Pristupa ZB, Niznik HB (2001). Direct binding and functional coupling of alpha‐synuclein to the dopamine transporters accelerate dopamine‐induced apoptosis. FASEB J 15: 916–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung TC, Lui CN, Chen LW, Yung WH, Chan YS, Yung KK (2012). Ceftriaxone ameliorates motor deficits and protects dopaminergic neurons in 6‐hydroxydopamine‐lesioned rats. ACS Chem Neurosci 3: 22–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou H, Montoya SE, Alerte TN, Wang J, Wu J, Peng X et al. (2010). Serine 129 phosphorylation reduces the ability of alpha‐synuclein to regulate tyrosine hydroxylase and protein phosphatase 2A in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem 285: 17648–17661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash DC, Ouyang Q, Pablo J, Basile M, Izenwasser S, Lieberman A et al. (2003). Cocaine abusers have an overexpression of alpha‐synuclein in dopamine neurons. J Neurosci 23: 2564–2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mash DC, Adi N, Duque L, Pablo J, Kumar M et al. (2008). Alpha synuclein protein levels are increased in serum from recently abstinent cocaine abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend 94: 246–250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massie A, Goursaud S, Schallier A, Vermoesen K, Meshul CK, Hermans E et al. (2010). Time‐dependent changes in GLT‐1 functioning in striatum of hemi‐Parkinson rats. Neurochem Int 57: 572–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath JC, Drummond GB, McLachlan EM, Kilkenny C, Wainwright CL (2010). Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol 160: 1573–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker D, Kim JH, Vezina P (1998). Depletion of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens prevents the generation of locomotion by metabotropic glutamate receptor activation. Brain Res 812: 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JS, Tallarida RJ, Unterwald EM (2009). Cocaine‐induced hyperactivity and sensitization are dependent on GSK3. Neuropharmacology 56: 1116–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JS, Barr JL, Harper LJ, Poole RL, Gould TJ, Unterwald EM (2014). The GSK3 Signaling Pathway Is Activated by Cocaine and Is Critical for Cocaine Conditioned Reward in Mice. PLoS ONE 9: e88026. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0088026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitani A, Tanaka K (2003). Functional changes of glial glutamate transporter GLT‐1 during ischemia: an in vivo study in the hippocampal CA1 of normal mice and mutant mice lacking GLT‐1. J Neurosci 23: 7176–7182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owesson‐White CA1, Roitman MF, Sombers LA, Belle AM, Keithley RB, Peele JL et al. (2012). Sources contributing to the average extracellular concentration of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem 121: 252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawson AJ, Sharman JL, Benson HE, Faccenda E, Alexander SP, Buneman OP et al. (2014). The IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY: an expert‐driven knowledgebase of drug targets and their ligands. Nucl Acids Res 42: D1098–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C (2009). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 6th edn. Academic: London. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez RG, Waymire JC, Lin E, Liu JJ, Guo F, Zigmond MJ (2002). A role for alpha‐synuclein in the regulation of dopamine biosynthesis. J Neurosci 22: 3090–3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Y, Ouyang Q, Pablo J, Mash DC (2005). Cocaine abuse elevates alpha‐synuclein and dopamine transporter levels in the human striatum. Neuroreport 16: 1489–1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen BA, Baron DA, Kim JK, Unterwald EM, Rawls SM (2011). β‐Lactam antibiotic produces a sustained reduction in extracellular glutamate in the nucleus accumbens of rats. Amino Acids 40: 761–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Van Kammen M, Levey AI, Martin LJ, Kuncl RW (1995). Selective loss of glial glutamate transporter GLT‐1 in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann Neurol 38: 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, Haenggeli C, Huang YH, Bergles DE et al. (2005). Beta‐lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature 433: 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzza P, Siligardi G, Hussain R, Marchiani A, Islami M, Bubacco L et al. (2014). Ceftriaxone blocks the polymerization of α‐synuclein and exerts neuroprotective effects in vitro. ACS Chem Neurosci 5: 30–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanberg PR, Zoloty SA, Willis R, Ticarich CD, Rhoads K, Nagy RP et al. (1987). Digiscan activity: automated measurement of thigmotactic and stereotypic behavior in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 27: 569–572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sari Y, Smith KD, Ali PK, Rebec GV (2009). Upregulation of GLT1 attenuates cue‐induced reinstatement of cocaine‐seeking behavior in rats. J Neurosci 29: 9239–9243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segovia G, Mora F (2001). Involvement of NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptors in the effects of endogenous glutamate on extracellular concentrations of dopamine and GABA in the nucleus accumbens of the awake rat. Brain Res Bull 54: 153–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segovia G, Del Arco A, Mora F (1997). Endogenous glutamate increases extracellular concentrations of dopamine, GABA, and taurine through NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptors in striatum of the freely moving rat: a microdialysis study. J Neurochem 69: 1476–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Grace AA (2010). Cortico–Basal Ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology 35: 27–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Carr DB, Omelchenko N, Pinto A (2003). Anatomical substrates for glutamate–dopamine interactions: evidence for specificity of connections and extrasynaptic actions. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1003: 36–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HW, Hagino Y, Kobayashi H, Shinohara‐Tanaka K, Ikeda K, Yamamoto H et al. (2004). Regional differences in extracellular dopamine and serotonin assessed by in vivo microdialysis in mice lacking dopamine and/or serotonin transporters. Neuropsychopharmacology 29: 1790–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sondheimer I, Knackstedt LA (2011). Ceftriaxone prevents the induction of cocaine sensitization and produces enduring attenuation of cue‐ and cocaine‐primed reinstatement of cocaine‐seeking. Behav Brain Res 225: 252–258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuber GD, Klanker M, de Ridder B, Bowers MS, Joosten RN, Feenstra MG et al. (2008). Reward‐predictive cues enhance excitatory synaptic strength onto midbrain dopamine neurons. Science 321: 1690–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallarida CS, Corley G, Kovalevich J, Yen W, Langford D, Rawls SM (2013). Ceftriaxone attenuates locomotor activity induced by acute and repeated cocaine exposure in mice. Neurosci Lett 556: 155–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tehranian R, Montoya SE, Van Laar AD, Hastings TG, Perez RG (2006). Alpha‐synuclein inhibits aromatic amino acid decarboxylase activity in dopaminergic cells. J Neurochem 99: 1188–1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trantham‐Davidson H, LaLumiere RT, Reissner KJ, Kalivas PW, Knackstedt LA (2012). Ceftriaxone normalizes nucleus accumbens synaptic transmission, glutamate transport, and export following cocaine self‐administration and extinction training. J Neurosci 32: 12406–12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezina P, Kim JH (1999). Metabotropic glutamate receptors and the generation of locomotor activity: interactions with midbrain dopamine. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 23: 577–589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward SJ, Rasmussen BA, Corley G, Henry C, Kim JK, Walker EA et al. (2011). Beta‐lactam antibiotic decreases acquisition of and motivation to respond for cocaine, but not sweet food, in C57Bl/6 mice. Behav Pharmacol 22: 370–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA (2004). Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 483–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu CM, Wang J, Wu P, Zhu WL, Li QQ, Xue YX et al. (2009). Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in the nucleus accumbens core mediates cocaine‐induced behavioral sensitization. J Neurochem 111: 1357–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu S, Zuo X, Li Y, Zhang C, Zhou M, Zhang YA et al. (2004). Inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase expression in alpha‐synuclein‐transfected dopaminergic neuronal cells. Neurosci Lett 367: 34–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan YH, Yan WF, Sun JD, Huang JY, Mu Z, Chen NH (2015). The molecular mechanism of rotenone‐induced α‐synuclein aggregation: emphasizing the role of the calcium/GSK3β pathway. Toxicol Lett 233: 163–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]