Abstract

Background

Oral manifestations are common in Crohn's disease (CD). Here we characterized the subgingival microbiota in pediatric CD patients initiating therapy and after 8 weeks to identify microbial community features associated with CD and therapy.

Methods

Pediatric CD patients were recruited from The Children's Hospital of Pennsylvania. Healthy control subjects were recruited from primary care or orthopedics clinic. Subgingival plaque samples were collected at initiation of therapy and after 8 weeks. Treatment exposures included 5-ASAs, immunomodualtors, steroids, and infliximab. The microbiota was characterized by 16S rRNA gene sequencing. The study was repeated in separate discovery (35 CD, 43 healthy) and validation cohorts (43 CD, 31 healthy).

Results

A majority of subjects in both cohorts demonstrated clinical response after 8 weeks of therapy (discovery cohort 88%, validation cohort 79%). At week 0, both antibiotic exposure and disease state were associated with differences in bacterial community composition. Seventeen genera were identified in the discovery cohort as candidate biomarkers, of which 11 were confirmed in the validation cohort. Capnocytophaga, Rothia, and TM7 were more abundant in CD relative to healthy controls. Other bacteria were reduced in abundance with antibiotic exposure among CD subjects. CD-associated genera were not enriched compared to healthy controls after 8 weeks of therapy.

Conclusions

Subgingival microbial community structure differed with CD and antibiotic use. Results in the discovery cohort were replicated in a separate validation cohort. Several potentially pathogenic bacterial lineages were associated with CD but were not diminished in abundance by antibiotic treatment, suggesting targets for additional surveillance.

Keywords: 16S, microbiome, infliximab

Introduction

Interactions between the host genome and environmental factors, notably the gut microbiota, are implicated in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Multiple recent studies have demonstrated associations between the composition of the intestinal microbiota and IBD, but the microbiota of the oral mucosa in CD is less well characterized. Oral manifestations are observed in 5-80% of pediatric CD patients.1-3 Pediatric patients with oral CD frequently develop manifestations prior to onset of gastrointestinal symptoms, allowing earlier diagnosis.2 All areas of the oral cavity can be involved in CD, with the most commonly affected being the buccal, gingival, and labial mucosa. Manifestations include prototypical gingival lesions, aphthous lesions, edema of the mucosa, gingivitis, and periodontitis. Gingival CD, a common oral finding, is described as cobblestone-like gingival alterations and significant thickening of the tissue. These are similar to the intestinal findings of active CD, often associated with isolated edema of the mucosa and aphthous lesions. As with intestinal CD, oral lesions frequently respond to therapy with antibiotics such as metronidazole.3 Thus, we sought to determine if alterations of the subgingival microbiota are associated with Crohn's disease and antibiotic therapy.

The structure of the oral microbiota has been previously associated with the development of periodontitis, gingivitis and dental caries.4-8 The epithelial layer in the subgingival crevice is the initial interface between peridontopathic organisms and the host.9, 10 The presence of bacteria in the subgingival environment can lead to the development of a biofilm, leading to an innate immune response associated with production of cytokines and anti-microbial peptides, reminiscent of responses at the mucosal interface in the gut.

Two prior studies evaluated the oral microbiota and CD, showing decreased diversity in patients with CD compared to healthy controls11 and bacterial infections associated with chronic periodonititis.11, 12 However, the reproducibility of these studies was not assessed, the effects of antibiotic use were not probed in detail, and longitudinal changes were not investigated.

In this study, we compared the subgingival oral microbiota in longitudinal samples from pediatric patients with CD and healthy controls to determine associations with disease, relative disease activity, and specific CD phenotypes. We then confirmed our findings with a second validation cohort. Our data demonstrate that CD and antibiotic exposure are each associated with separate components of the oral microbiota.

Materials and Methods

Study Subjects

The study was approved by The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board (protocol IRB 11-008043). Patients with CD and healthy controls were recruited from The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia between July 2011 and April 2013. Subjects aged 2 - 21 were eligible for inclusion, a range spanning early childhood to late adolescence as defined in NICHD pediatric terminology.13 Patients with CD were recruited from the Gastroenterology inpatient and outpatient service. Healthy control subjects were recruited from primary care or orthopedics clinic. Subjects with a known history of medical or systemic disease, including medical conditions likely to influence nutrient intake, intestinal transit, or bowel health were excluded from the healthy control group. Demographic, dietary, and phenotypic data were collected on each subject enrolled. Subjects were asked to continue their routine, and all subjects had nothing to eat or drink for 30 minutes prior to oral sampling. Mouthwash use was recorded at the time of sampling. Sampling occurred once at the start of the study (week 0) and again following 8 weeks of therapy (week 8). The entire study was repeated using independent discovery and validation cohorts.

Disease activity was measured using the Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) and fecal calprotectin (FCP). The PCDAI was measured at baseline and week 8. Moderate disease activity was defined as PCDAI ≥ 20. Clinical response was defined as a reduction in PCDAI from week 0 to week 8 by ≥ 12.5 points or PCDAI ≤ 10 at week 8. FCP concentration was measured (Genova Diagnostics) at week 0 and week 8 as a marker of intestinal mucosal inflammation in a subset of patients. For this study, moderate disease activity was defined as an FCP level ≥ 250 μg/g. Response was defined as greater than 30% reduction in FCP level between week 0 and week 8. If FCP was missing at either week, an analysis for FCP response was not performed.

Subgingival Sampling

Subgingival plaque samples were collected at week 0 and week 8. The subgingival area was selected for sequencing because bacterial populations embedded in mucus and biofilms in this area are likely to be in more direct contact with the host immune system, compared to saliva or other oral locations. Samples were collected from the subgingival space via a sterile microbrush and stored at -80°C. The oral mucosa was examined at the time of sampling for the presence of gingival disease and ulceration. No patient had evidence of periodontitis or gingival disease.

Sample Processing and DNA Sequencing

DNA was isolated from the microbrush using the PSP Spin Stool DNA Plus Kit (STRATEC Molecular, Berlin, Germany). The microbrush tips were cut directly into bead tubes containing 300μL stool stabilizer, and bead beaten for 1 minute. For liquid samples, 1.4mL was centrifuged at 13,400g for 10 minutes. Tubes were incubated at 70°C for 10 minutes. DNA was then extracted per manufacturer's instructions and stored at -20°C. We amplified bacterial 16S rRNA genes using barcoded V1V2 primers14 and AccuPrime Taq DNA polymerase High Fidelity (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Products were pooled, purified, and pyrosequenced on a 454 Life Sciences FLX instrument (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Brandford, CT).

Sequence data was processed using the QIIME analytical pipeline (version 1.8).15 To assign reads to samples, we required an exact match to the sample-specific barcode and the PCR primer sequence. Reads were discarded if more than one base call was undetermined (N) or the expected PCR primer sequence was not found at the end of the read. Reads were assigned to operational taxonomic units (OTUs) in the Greengenes database (version 13_8) at a threshold of 97% similarity using UCLUST (version 1.2.22q).16,17 Reads not matching to a 16S sequence in the reference database were removed from the analysis (2% of input).

Sequence data was deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under accession numbers SRP057992 (discovery cohort data) and SRP058007 (validation cohort data).

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed in R.18 Community structure was compared using pairwise UniFrac distances, which measure the fraction of total phylogenetic branch length that is unique to bacteria from either sample in the pair. Communities were analyzed both on the basis of shared membership (unweighted UniFrac)19 and differences in OTU proportions (weighted UniFrac).20 The relationship of community structure to metadata was assessed with the PERMANOVA test, which uses pairwise sample distances to test a null hypothesis of no difference between groups.21 Type II sums of squares were used to assess the effects of antibiotics and disease state. Pairwise sample distances were ordinated using principal coordinates analysis.

The Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare genus abundance between three groups. The Mann-Whitney test was used for two-group comparisons. We did not test for abundance differences when a genus appeared in fewer than 10 samples (for rank tests with 9 non-zero values, the best case scenario yields only 126/2=63 possible orderings for a two-tailed test). When multiple comparisons were performed, P-values were corrected using the procedure of Benjamini and Hochberg to control for false discovery rate.22

Results

Clinical characteristics

The discovery cohort was comprised of 35 patients with CD and 46 heathy control subjects. The age range was 6 – 17 years old in the CD group and 5 – 20 years old in the healthy control group. The median age was 13 in both groups. Disease location in the CD group was predominately ileocolonic (80% of patients). Duration of disease ranged from one month to six years. Disease activity was moderate or severe at week 0 in 83% (PCDAI) and 82% (FCP) of patients with CD. Medications at week 0 included corticosteroids, immunomodulators (6-MP, methotrexate), enteral therapy, antibiotics, and 5-ASAs. The majority of patients in this cohort were recruited at week 0 of initiation of infliximab therapy. At week 8, the 30 patients scheduled to receive infliximab had completed the induction regimen and received three doses. At week 8, 88% and 82% of all patients with CD demonstrated response in PCDAI and FCP respectively, reflecting improvement in disease status.

For the validation cohort, 44 patients with CD and 31 healthy control subjects were recruited. The age ranged from 2 to 18 years in the CD group and 3 to 21 years in the healthy control group. Median age was 13 years for both groups. Duration of disease ranged from 1 week to 6 months. Disease activity was quantified primarily by PCDAI, and was moderate or severe in 83% of CD patients at week 0. FCP levels were available for only 15 patients in the validation cohort, and no patient was measured at both week 0 and week 8. Medications at week 0 included 5-ASAs, antibiotics, immunomodulators, corticosteroids and nutritional therapy. Patients had no prior biologic therapy (including infliximab) exposure at week 0. Fourteen CD patients were initiated on infliximab therapy by week 8. At week 8, 88% of CD patients in the validation cohort demonstrated a response in PCDAI.

Several characteristics of the discovery cohort differed from those of the validation cohort (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which lists details for both study cohorts). The validation cohort contained substantially fewer patients initiating therapy with infliximab relative to the discovery cohort (13/43 vs. 30/35 patients, respectively). The proportion of patients with moderate or severe disease activity was lower in the validation cohort. Despite these differences, the two cohorts are representative of clinical response across a wide range of ages and therapies.

Sequencing results

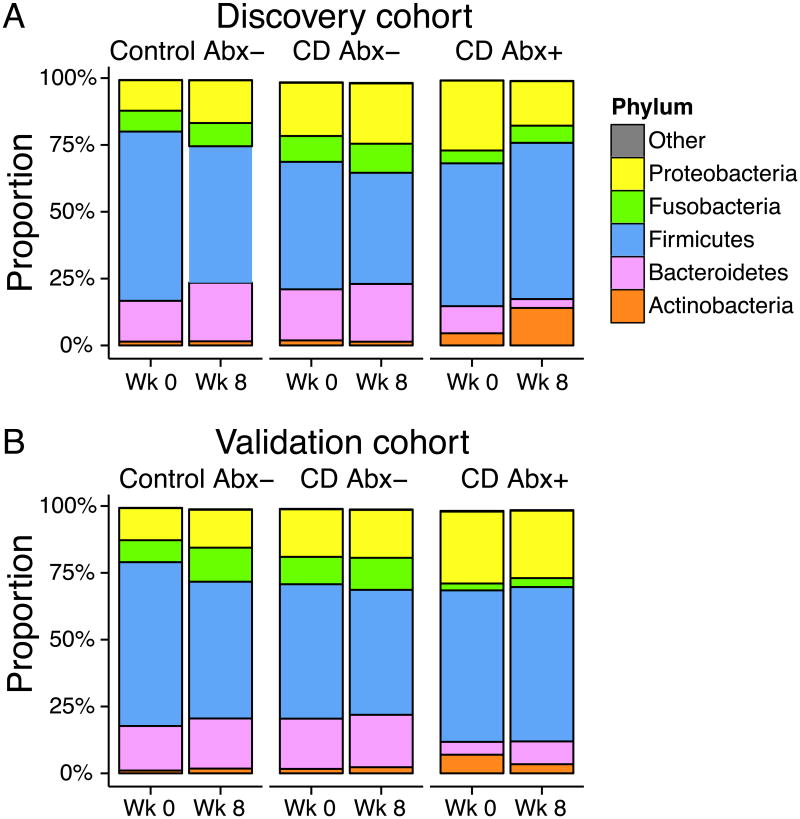

A total of 322,000 reads were obtained for samples in the discovery cohort, and 304,000 for the validation cohort. Samples having fewer than 200 reads were removed from the analysis. The median number of reads per sample was 1506 for the discovery cohort and 1377 for the validation cohort. Taxonomic assignment of sequence reads revealed a bacterial community composition similar to that reported previously for subgingival plaque (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which contains heat maps of bacterial taxa observed).23 Five phyla were prominent in the data set: Actinobacteria, Bacteroides, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Summary of bacterial phyla observed in the discovery and validation cohorts.

Proportions of the five dominant bacterial phyla identified in 16S tag sequencing results from subgingival brushing samples. Patients with CD were sampled prior to initiation of therapy and again after 8 weeks. CD subjects currently receiving antibiotics (CD Abx+) are summarized separately from other CD patients (CD Abx-). Healthy control subjects (Control Abx-) were sampled at the same time interval and were not exposed to antibiotics during the study or 2 months prior. The study was repeated using separate (A) discovery and (B) validation cohorts.

A combined model of bacterial community composition reveals independent signatures of Crohn's disease and antibiotic use

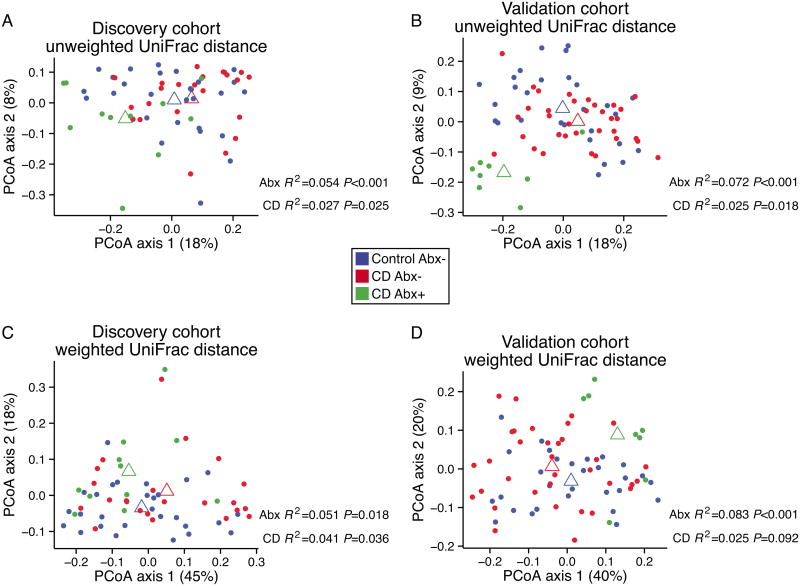

We first compared the subgingival microbial community structure in CD to that of healthy controls at week 0. Figure 2 presents ordinations of pairwise UniFrac distances for the discovery and validation cohorts. To assess the magnitude and significance of differences in UniFrac distance between groups, we built a combined model that fit the effects of antibiotic use and disease state.

Figure 2. Analysis of bacterial community composition in the discovery and validation cohorts.

Communities were compared to determine differential membership using unweighted UniFrac distance (A, B) or community proportional abundance using weighted UniFrac distance (C, D). Samples were ordinated using principal coordinate analysis. Open triangles represent the group centroid position for healthy control subjects (blue), CD patients not on antibiotics (red), and CD patients on antibiotics (green). The PERMANOVA test was used to assess association of sample-sample distance with disease state (CD) and current antibiotic usage (Abx).

We found that current antibiotic use produced substantial alterations in the bacterial community structure of the discovery cohort (unweighted UniFrac P<0.001, weighted UniFrac P=0.02). This observation was confirmed in data from the validation cohort (unweighted UniFrac P<0.001, weighted UniFrac P<0.001).

Patients in the discovery cohort showed differences associated with CD in both unweighted (P=0.025) and weighted UniFrac distance (P=0.036), though the size of the effect was roughly half that of antibiotic use. For the validation cohort, we observed a difference in unweighted UniFrac distance associated with disease state (P=0.018), but only a trend in the weighted analysis (P=0.09). The estimated effect size for unweighted UniFrac distance was similar in the discovery and validation cohorts (R2=0.027 and 0.025, respectively).

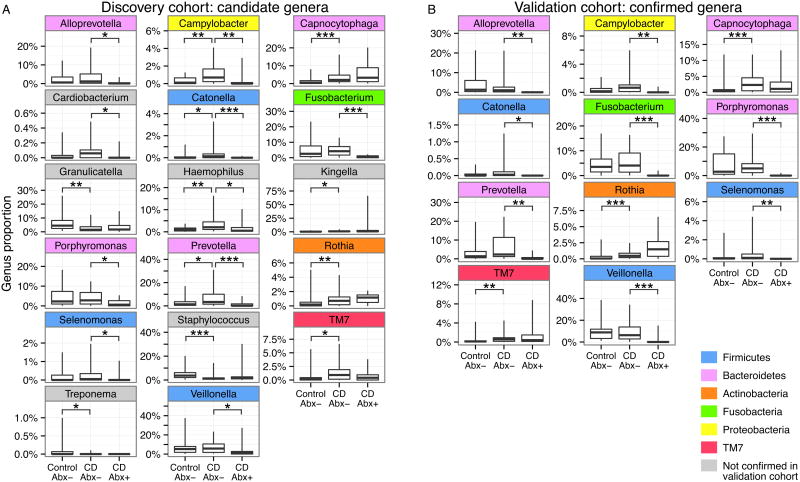

We next sought to determine the specific bacterial lineages responsible for the differences in community composition. Using a Kruskal-Wallis test, we identified 17 candidate genera in the discovery cohort that contributed to the difference in the subgingival microbiota between healthy controls, CD without current antibiotics, and CD with current antibiotics (Figure 3A). We also found that the abundance of the TM7 phylum differed between the three groups. Because TM7 appeared in low abundance (about 1% of total) and because the phylum contained no genera in the Greengenes taxonomy, we chose to include it in the list of candidate genera.

Figure 3. Genera identified as candidate biomarkers in the discovery cohort and confirmed in the validation cohort.

(A) Candidate genera differing between healthy control subjects (Control Abx-), CD subjects not on antibiotics (CD Abx-), and CD subjects currently on antibiotics (CD Abx+) in the discovery cohort at week 0 (* P<0.05, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001). (B) Genera confirmed to be differing in the validation cohort at week 0. Confirmed genera are color-coded according to phylum.

Eleven of the 17 candidate genera were confirmed in the validation cohort (Figure 3B). We again used the Kruskal-Wallis test to detect differences between healthy controls, CD subjects not on antibiotics, and CD subjects receiving antibiotics. The confirmed genera were Alloprevotella (P=0.003), Campylobacter (P=0.02), Capnocytophaga (P=0.01), Catonella (P=0.02), Fusobacterium (P=0.003), Porphyromonas (P=0.003), Prevotella (P=0.006), Rothia (P=0.003), Selenomonas (P=0.01), TM7 (P=0.02), and Veillonella (P=0.005).

In the validation cohort, we found that Capnocytophaga (P=0.001), Rothia (P=0.001), and TM7 (P=0.004) were significantly different between healthy controls and CD subjects not on antibiotics (Mann-Whitney test; see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which lists test results for all comparisons at week 0). All were increased in the CD group relative to healthy controls. We performed the same comparisons on the discovery cohort data and obtained identical results. Thus, we observed reproducible differences in the subgingival microbiota associated with pediatric Crohn's disease.

We returned to the validation cohort to make follow-up comparisons of genus abundance between subjects in the CD group receiving antibiotics and CD subjects not on antibiotics. Patients on antibiotics had a decreased proportion of Alloprevotella (P=0.002), Campylobacter (P=0.005), Catonella (P=0.02), Fusobacterium (P<0.001), Porphyromonas (P<0.001), Prevotella (P=0.002), Selenomonas (P=0.003), and Veillonella (P=0.005). The antibiotics used were Ciprofloxicin, Flagyl, and Vancomycin, which have broad specificities that include the above lineages. The taxonomic alterations associated with antibiotic use here resemble some of those previously described in the oral microbiota following therapy for periodontitis.7, 8 The antibiotics-associated differences in genus abundance were also observed in the discovery cohort. Thus, we conclude that antibiotics affected a separate set of genera, apart from those associated with CD.

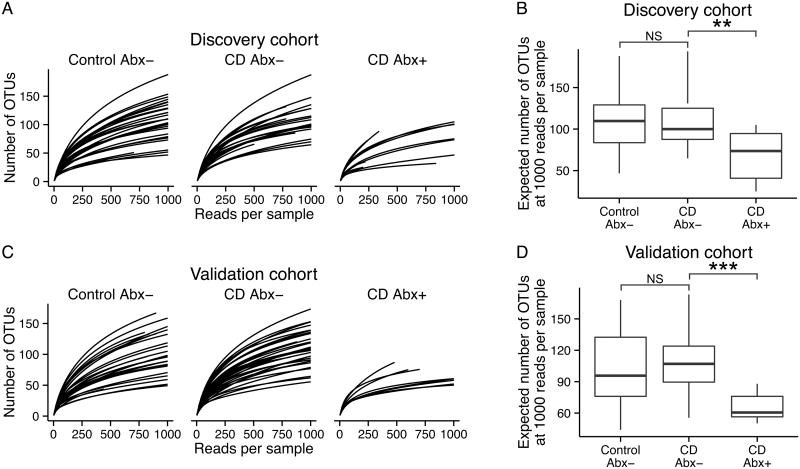

We wondered whether the changes associated with antibiotic use might be attributable to loss of species within the identified genera. Rarefaction analysis (Figure 4) showed that community richness was lower in CD subjects treated with antibiotics relative to other CD subjects, for both the discovery (Mann-Whitney P=0.009) and validation (P<0.001) cohorts. We did not detect differences in richness between healthy controls and CD subjects not on antibiotics (discovery cohort P=0.6, validation cohort P=0.16).

Figure 4. Antibiotic use is associated with lower bacterial diversity.

(A) Rarefaction curves representing the expected number of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) observed in 16S sequencing results from healthy controls (Control Abx-), CD patients not on antibiotics (CD Abx-), and CD patients receiving antibiotics (CD Abx+) at week 0 in the discovery cohort. (B) Boxplots showing expected number of OTUs at 1000 reads per sample in the discovery cohort at week 0. (C) Rarefaction curves and (D) boxplots for the validation cohort at week 0. In both cohorts, CD patients on antibiotics have fewer OTUs per sample than CD patients not on antibiotics or healthy controls (Mann-Whitney test, ** P<0.01, *** P<0.001).

Disease activity is not associated with alteration of the subgingival microbiota

We then analyzed samples to determine whether community structure or specific taxa correlated with the level of disease activity. At week 0 in the discovery cohort, 83% of subjects had active disease, based on PCDAI value. We observed no association between community composition and PCDAI value (unweighted UniFrac P=0.46, weighted UniFrac P=0.46). FCP level was likewise not correlated with pairwise UniFrac distance in the discovery cohort (unweighted UniFrac P=0.55, weighted UniFrac P=0.26). No differences were found in particular subgingival bacterial lineages correlating with measures of disease activity in the discovery cohort.

In the validation cohort at week 0, 49% of subjects had active disease based on PCDAI value. As in the discovery cohort, bacterial community composition was not associated with PCDAI (unweighted UniFrac P=0.18, weighted UniFrac P=0.26). Evidently, disease activity at week 0 was not strongly correlated with subgingival community structure.

Differences in microbial community structure associated with CD resolve after 8 weeks of therapy

We next asked whether the subgingival microbiota changed following effective treatment. Bacterial community composition was analyzed by comparing pairwise UniFrac distances in the set of samples obtained at week 8 (see Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 4). Differences between CD and healthy control samples observed at baseline were not detected at week 8 (unweighted UniFrac P=0.19, weighted UniFrac P=0.28 for discovery cohort; unweighted UniFrac P=0.18, weighted UniFrac P=0.28 for validation). Conversely, differences due to antibiotic use persisted at week 8 (P≤0.001, weighted and unweighted UniFrac in both cohorts).

Analysis of confirmed genera from week 0 reinforced the conclusions from the community-level analysis (see Table, Supplemental Digital Content 5, and Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 6). Four genera that were reduced with antibiotic use at week 0 also decreased at week 8 for both cohorts: Alloprevotella (discovery cohort P=0.03, validation cohort P=0.04), Fusobacterium (P=0.02 and P<0.001), Porphyromonas (P=0.01 and P=0.001), and Prevotella (P=0.007 and P=0.009). Other antibiotic-associated genera were not found to be different in both cohorts. The taxa associated with disease state at week 0 did not differ between healthy controls and CD subjects in either the discovery or validation cohort at week 8 (Capnocytophaga P=0.2 and P=0.5, Rothia P=0.3 and P=0.2, TM7 P=0.4 and P=0.5 in the discovery and validation cohorts, respectively). Thus, we conclude that 8 weeks of therapy was sufficient to resolve observed differences in the subgingival microbiota associated with CD.

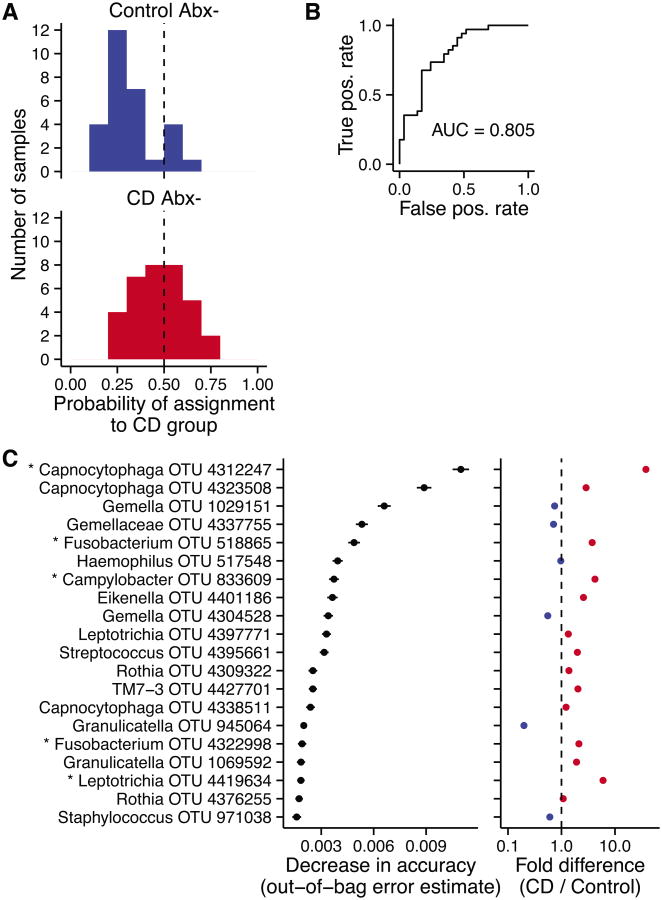

A machine learning approach identifies a characteristic signature of CD in pediatric subgingival samples

Given that a distinctive signal was seen in week 0 samples associated with CD, we asked whether we could identify a predictive microbial signature potentially of use in molecular diagnosis. We used the random forest method to create a predictive classifier that sorted CD subjects from healthy controls based solely on data from the discovery cohort.24 Because of the relatively strong antibiotics effect, we excluded CD subjects taking antibiotics at week 0 from the random forest analysis. Using the discovery cohort data, we were able to make a classifier that sorted CD samples from healthy control samples with 27% error. The classifier was then applied to the validation cohort (Figure 5A), where 83% of the healthy samples were classified correctly. However, only 15 of the 34 total CD samples were correctly identified, indicating that random forest classification is relatively specific but not sensitive at a probability threshold of 0.5.

Figure 5. A random forest classifier trained on Discovery Cohort samples.

(A) Probability of CD assignment for samples in the validation cohort at week 0 based on a random forest classifier trained on the week 0 discovery cohort data. (B) The receiver operating characteristic curve for the classifier, which plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate. A perfect classifier would have an “area under the curve” of 1, and a random classifier would score 0.5. (C) The 20 most important OTUs for classification are shown, ordered by an out-of-bag estimate for mean decrease in accuracy when that OTU is removed. The fold difference in OTU proportion is shown to the right: OTUs that are more abundant in CD samples appear to the right of the dashed line.

Classification sensitivity can be improved if more false positives are acceptable. To evaluate the performance of the classifier at all threshold values, we constructed a receiver operating characteristic curve (Figure 5B). The area under the curve was 0.8, meaning that 80% of the time a randomly selected CD sample will have a higher probability for CD assignment than a randomly selected healthy sample.

The random forest classifier placed high importance on OTUs from Capnocytophaga, Rothia, and TM7, taxa identified as differentially abundant between the CD and healthy groups at week 0. Figure 5C lists the 20 most important OTUs as determined by a mean decrease in accuracy for the classifier (out-of-bag estimate). Two Capncytophaga OTUs were ranked highest in importance for the classifier, the first of which was found to be increased more than tenfold in the CD group. Other OTUs had a modest difference between groups but were used collectively by the classifier to improve accuracy. Thus, the random forest signature provides a molecular marker for discriminating CD and healthy controls.

Discussion

Here we report that the composition of the subgingival oral microbiota in active Crohn's disease differs from healthy control subjects. The CD signature was seen in the absence of gingival disease, and was replicated in a validation cohort, demonstrating the reproducibility of these findings. The CD signature was not present in samples obtained after 8 weeks of the study, suggesting that the CD community structure was altered in association with successful therapy.

We identified three taxa that were enriched in the CD group at the initial time point: Capnocytophaga, Rothia, and TM7. Although these taxa are part of the normal subgingival flora, they have each been implicated in disease and provide a basis for further investigation as environmental mediators of CD pathogenesis. We found that 8 weeks of therapy were sufficient to return these taxa to healthy levels. These three taxa were not among those affected by antibiotic use.

Capnocytophaga, a facultative anaerobic Gram-negative bacillus, is part of the commensal oral flora, but is enriched in subgingival plaque relative to other oral surfaces.23 It is an opportunistic pathogen, and is associated with periodontal disease, particularly in immunocompromised patients.25-27 It is most often detected in the setting of mucosal ulcerations, gingivitis and bleeding gums. It has been shown to lead to systemic infection in immunocompromised patients, particularly children, presenting with oral ulcers and decreased granulocytes.28 Additionally, it has been detected in higher abundance in patients with Type 1 diabetes mellitus.29

The genus Rothia is also a member of the commensal subgingival flora. Although early studies found it to be enriched in periodontitis subjects,30 it has been associated with periodontal health in several deep sequencing studies.31-33 Rothia species may have important interactions with the host immune system that give rise to a role in inflammatory diseases such as CD. The type species, Rothia dentocariosa, was previously shown to increase TNF-α production in vitro, and thus may act as an agent for increased inflammation in the oral cavity.34 More importantly, Rothia may be an opportunistic pathogen in subjects with impaired immune function. Recently, R. dentocaiosa was implicated in a case of bacteremia in a subject receiving infliximab, the same therapy used in this study.35

The TM7 division was previously associated with CD in samples of colonic mucosa. The diversity of TM7 organisms in colonic biopsies, many showing >99% 16S similarity to oral clones, was increased in a previous study of adult subjects with Crohn's disease.36 In the same study, the diversity of TM7 bacteria was not increased in subjects with ulcerative colitis, indicating an involvement with CD specifically.36 In the oral cavity, a number of studies have found associations between TM7 bacteria and periodontitis.31, 37, 38 Because the organisms have never been grown in culture, mechanisms for involvement in inflammatory disease remain unclear. However, assembly of a TM7 genome from metagenomic data revealed some potential virulence factors in one study.38

We found that Alloprevotella, Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, and Prevotella were consistently decreased in the antibiotic-exposed CD group, compared to CD subjects not using antibiotics. The measurement was repeated at two time points in each of two independent study cohorts. Previous studies have documented similar microbial changes following antibiotic therapy in periodontitis.7 Species from all four genera, Alloprevotella, Fusobacterium, Porphyromonas, and Prevotella, were previously reported to be less prevalent in subjects responding to antibiotic therapy for periodontitis.7 Here we report parallel changes in the patients with IBD exposed to antibiotics. The same study reported increased prevalence of the CD-associated genera identified here, Capnocytophaga and Rothia. Although these groups were not increased in association with antibiotic use in our data, the published data suggest the possibility that antibiotic exposure promoted colonization by these CD-associated organisms.

In summary, we document extensive alterations of the subgingival microbiota associated with CD and antibiotic use. These findings and those of others39-42 provide a tractable model for studies of microbiota interactions at the subgingival mucosal surface, where sampling is simpler than for intestinal sites. This accessibility was leveraged here to allow acquisition of separate discovery and validation cohorts, providing much more secure conclusions than is possible in studies of single cohorts in isolation. The lineages consistently enriched in abundance provide specific candidates for new rounds of studies of mechanisms of disease and antibiotic therapies. The random forest analysis provides a diagnostic signature, allowing potential discrimination of CD and healthy controls based on convenient oral sampling. In future work, it will be of interest to determine whether such signatures can be sharpened and used to partition patients into groups that are relatively more responsive to specific IBD therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by Project UH3DK083981; Molecular Biology Core of the Penn Digestive Disease Center (P30 DK050306); The Joint Penn-CHOP Center for Digestive, Liver, and Pancreatic Medicine; S10RR024525; UL1RR024134, and K24-DK078228; and the University of Pennsylvania Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) P30 AI 045008, and CCFA Career Development Award (3276). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health, or Pennsylvania Department of Health.

Footnotes

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

References

- 1.Plauth M, Jenss H, Meyle J. Oral manifestations of Crohn's disease. An analysis of 79 cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991;13:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pittock S, Drumm B, Fleming P, et al. The oral cavity in Crohn's disease. J Pediatr. 2001;138:767–771. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.113008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harty S, Fleming P, Rowland M, et al. A prospective study of the oral manifestations of Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:886–891. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00424-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hovav AH. Dendritic cells of the oral mucosa. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:27–37. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Benedetto A, Gigante I, Colucci S, et al. Periodontal disease: linking the primary inflammation to bone loss. Clin Dev Immunol. 2013;2013:503754. doi: 10.1155/2013/503754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teles R, Teles F, Frias-Lopez J, et al. Lessons learned and unlearned in periodontal microbiology. Periodontol 2000. 2013;62:95–162. doi: 10.1111/prd.12010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colombo AP, Bennet S, Cotton SL, et al. Impact of periodontal therapy on the subgingival microbiota of severe periodontitis: comparison between good responders and individuals with refractory periodontitis using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1279–1287. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mdala I, Olsen I, Haffajee AD, et al. Multilevel analysis of bacterial counts from chronic periodontitis after root planing/scaling, surgery, and systemic and local antibiotics: 2-year results. J Oral Microbiol. 2013;5 doi: 10.3402/jom.v5i0.20939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Handfield M, Mans JJ, Zheng G, et al. Distinct transcriptional profiles characterize oral epithelium-microbiota interactions. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:811–823. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung WO, An JY, Yin L, et al. Interplay of protease-activated receptors and NOD pattern recognition receptors in epithelial innate immune responses to bacteria. Immunol Lett. 2010;131:113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Docktor MJ, Paster BJ, Abramowicz S, et al. Alterations in diversity of the oral microbiome in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:935–942. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brito F, Zaltman C, Carvalho AT, et al. Subgingival microflora in inflammatory bowel disease patients with untreated periodontitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:239–245. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835a2b70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams K, Thomson D, Seto I, et al. Standard 6: Age Groups for Pediatric Trials. Pediatrics. 2012;129:S153–S160. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0055I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenna P, Hoffmann C, Minkah N, et al. The macaque gut microbiome in health, lentiviral infection, and chronic enterocolitis. Plos Pathog. 2008;4 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. 2010;7:335–336. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2460–2461. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald D, Price MN, Goodrich J, et al. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012;6:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.R Core Team. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lozupone C, Knight R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:8228–8235. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lozupone CA, Hamady M, Kelley ST, et al. Quantitative and qualitative beta diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:1576–1585. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01996-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson MJ. A new method for non-parametric multivariate analysis of variance. Austral Ecol. 2001;26:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate - a Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. J Roy Stat Soc B Met. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Segata N, Haake SK, Mannon P, et al. Composition of the adult digestive tract bacterial microbiome based on seven mouth surfaces, tonsils, throat and stool samples. Genome Biol. 2012;13 doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-6-r42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Breiman L. Random forests. Mach Learn. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonatti H, Rossboth DW, Nachbaur D, et al. A series of infections due to Capnocytophaga spp in immunosuppressed and immunocompetent patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2003;9:380–387. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0691.2003.00538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sixou JL, Aubry-Leuliette A, De Medeiros-Battista O, et al. Capnocytophaga in the dental plaque of immunocompromised children with cancer. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006;16:75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim JA, Hong SK, Kim EC. Capnocytophaga sputigena bacteremia in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Lab Med. 2014;34:325–327. doi: 10.3343/alm.2014.34.4.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell JR, Edwards MS. Capnocytophaga species infections in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1991;10:944–948. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199112000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakalauskiene J, Kubilius R, Gleiznys A, et al. Relationship of clinical and microbiological variables in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus and periodontitis. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1871–1877. doi: 10.12659/MSM.890879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kumar PS, Griffen AL, Barton JA, et al. New bacterial species associated with chronic periodontitis. J Dent Res. 2003;82:338–344. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abusleme L, Dupuy AK, Dutzan N, et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. Isme Journal. 2013;7:1016–1025. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kistler JO, Booth V, Bradshaw DJ, et al. Bacterial Community Development in Experimental Gingivitis. Plos One. 2013;8 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Griffen AL, Beall CJ, Campbell JH, et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. Isme Journal. 2012;6:1176–1185. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kataoka H, Taniguchi M, Fukamachi H, et al. Rothia dentocariosa induces TNF-alpha production in a TLR2-dependent manner. Pathog Dis. 2014;71:65–68. doi: 10.1111/2049-632X.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yeung DF, Parsa A, Wong JC, et al. A Case of Rothia dentocariosa Bacteremia in a Patient Receiving Infliximab for Ulcerative Colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:297–298. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuehbacher T, Rehman A, Lepage P, et al. Intestinal TM7 bacterial phylogenies in active inflammatory bowel disease. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1569–1576. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brinig MM, Lepp PW, Ouverney CC, et al. Prevalence of bacteria of division TM7 in human subgingival plaque and their association with disease. Appl Environ Microb. 2003;69:1687–1694. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.3.1687-1694.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu B, Faller LL, Klitgord N, et al. Deep Sequencing of the Oral Microbiome Reveals Signatures of Periodontal Disease. Plos One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Teles R, et al. Effect of periodontal therapy on the subgingival microbiota over a 2-year monitoring period. I. Overall effect and kinetics of change. J Clin Periodontol. 2013;40:771–780. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santos BR, Demeda CF, Silva EE, et al. Prevalence of subgingival Staphylococcus at periodontally healthy and diseased sites. Braz Dent J. 2014;25:271–276. doi: 10.1590/0103-6440201302285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lourenco TG, Heller D, Silva-Boghossian CM, et al. Microbial signature profiles of periodontally healthy and diseased patients. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:1027–1036. doi: 10.1111/jcpe.12302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scher JU, Bretz WA, Abramson SB. Periodontal disease and subgingival microbiota as contributors for rheumatoid arthritis pathogenesis: modifiable risk factors? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2014;26:424–429. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0000000000000076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.