Abstract

Introduction

Little current research examines associations between infant mortality and US states’ funding for family planning services and for abortion, despite growing efforts to restrict reproductive rights and services and documented associations between unintended pregnancy and infant mortality.

Material and methods

We obtained publicly available data on state-only public funding for family planning and abortion services (years available: 1980, 1987, 1994, 2001, 2006, and 2010) and corresponding annual data on US county infant death rates. We modeled the funding as both fraction of state expenditures and per capita spending (per woman, age 15–44). State-level covariates comprised: Title X and Medicaid per capita funding, fertility rate, and percent of counties with no abortion services; county-level covariates were: median family income, and percent: black infants, adults without a high school education, urban, and female labor force participation. We used Possion log-linear models for: (1) repeat cross-sectional analyses, with random state and county effects; and (2) panel analysis, with fixed state effects.

Results

Four findings were robust to analytic approach. First, since 2000, the rate ratio for infant death comparing states in the top funding quartile vs. no funding for abortion services ranged (in models including all covariates) between 0.94 and 0.98 (95% confidence intervals excluding 1, except for the 2001 cross-sectional analysis, whose upper bound equaled 1), yielding an average 15% reduction in risk (range: 8–22%). Second, a similar risk reduction for state per capita funding for family planning services occurred in 1994. Third, the excess risk associated with lower county income increased over time, and fourth, remained persistently high for counties with a high percent of black infants.

Conclusions

Insofar as reducing infant mortality is a government priority, our data underscore the need, despite heightened contention, for adequate public funding for abortion services and for redressing health inequities.

Keywords: Abortion, Family planning, Health inequities, Infant mortality, Reproductive justice, Social policy

Highlights

-

•

Topic: US infant death rates + state abortion & family planning funding (1980–2010).

-

•

US infant deaths & state funding for abortion inversely associated (2001, 2006, 2010).

-

•

Inverse association of infant deaths & state funding for family planning only in 1994.

-

•

Excess mortality risk for black infants high throughout and rose for low income.

-

•

For reproductive justice, need adequate public funding for abortion & health equity.

1. Introduction

The infant mortality rate is well-recognized as a fundamental measure of societal well-being (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, David and Collins, 2014). Acutely sensitive to economic, racial/ethnic, and gender inequality and to abridgment of reproductive rights (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, David and Collins, 2014), infant mortality is both associated with unintended pregnancy (SACIM, 2016; Finer & Zolna, 2014; Tsui, McDonald-Mosley & Burke, 2010), and serves as a gauge for infant morbidity and maternal mortality (SACIM, 2016). In 2008, an estimated 41% of births globally (Singh, Sedgh & Hussain, 2010) and 49% of US births (Finer & Zolna, 2014) were unintended pregnancies, with risk highest among impoverished women (Finer and Zolna, 2014, Tsui et al., 2010, Singh et al., 2010).

Contributing to risk of unintended pregnancies and their sequelae are inadequate reproductive health policies and resources (Gruskin, 2013, Frost et al., 2015). These include lack of awareness of and access to such goods and services as appropriate contraceptives, family planning services, and abortion procedures (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, David and Collins, 2014, Finer and Zolna, 2014, Tsui et al., 2010, Singh et al., 2010, Gruskin, 2013, Frost et al., 2015). Within the United States, evidence that increased state funding for family planning and abortion services can lower infant mortality rates, especially for low-income women of color (Grossman and Jacobwitz, 1981, Corman and Grossman, 1985, Joyce, 1987a, Joyce, 1987b, Meier and McFarlane, 1994, McFarlane and Meier, 1998, McFarlane and Meier, 2001), is provided by a handful of studies, initially conducted in the 1980s (Grossman and Jacobwitz, 1981, Corman and Grossman, 1985, Joyce, 1987a, Joyce, 1987b), and followed by a few that extended the data through 1998 (Meier and McFarlane, 1994, McFarlane and Meier, 1998, McFarlane and Meier, 2001). No studies to our knowledge have reported on these associations since 1998.

Suggesting it would be worthwhile to extend the time frame of analyses are several salient temporal changes: (a) declines in the infant mortality rate and changes in its recognized determinants (e.g., socially patterned declines in smoking during pregnancy and increases in gestational diabetes) (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, Singh and Kogan, 2007); (b) declines in state funding for both reproductive health services (Sonfield and Gold, 2012, Schreiber and Traxler, 2015) and other social services influencing risk of infant mortality (Clayton and Pontusson, 1998, Rabarison, 2016); and (c) shifts in rates of contraceptive use (by type), unintended pregnancies, and use of abortion services (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, Finer and Zolna, 2014, Rabarison, 2016, Jones et al., 2012, Frost et al., 2010, Kost, 2015, Jones and Kavanaugh., 2011, Jacobs and Stanfors, 2015). Thus, at this time of sharp debate over growing restrictions affecting provision of family planning and abortion services (Gruskin, 2013, Schreiber and Traxler, 2015, Gee, 2014, Devi, 2015), it is important to test the hypothesis that inverse associations continue to exist between provisions of these services and infant mortality rates.

We obtained data to analyze, for 1980–2010, associations between infant mortality and US state-only funding for family planning and abortion services, using data for the six years for which high quality publicly available data exist for these state expenditures (1980, 1987, 1994, 2001, 2006, and 2010) (Sonfield & Gold, 2012).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Exposure data: state expenditures on family planning and abortion services

Numerous theoretical frameworks for analyzing societal determinants of health and health inequities, as employed in social epidemiology, political sociology, and health policy, emphasize the joint importance of resources, rights, and governance, including for reproductive health and reproductive justice (Krieger, 2011, Cottingham et al., 2010, Silliman et al., 2004). We accordingly focused on state-only expenditures for family planning and abortion services as the exposure of interest. These measures provide quantifiable evidence of state support for these services (Corman and Grossman, 1985, Joyce, 1987a, Joyce, 1987b, Meier and McFarlane, 1994, McFarlane and Meier, 1998, McFarlane and Meier, 2001) and avoid well-known difficulties in assessing implementation and enforcement of enacted legislation (Winter, 2012, Cole and Fielding, 2007). We obtained these high quality state-only funding data from a unique series of periodic reports issued by the Guttmacher Institute, which were designed to be compared validly over time (Sonfield & Gold, 2012). State family planning services, as defined in these reports, comprise “the package of direct patient care services provided through family planning programs to clients receiving reversible contraceptives” [Sonfield & Gold, 2012, p. 5].

For each of the six years for which the Guttmacher data were available (1980, 1987, 1994, 2001, 2006, and 2010) (Sonfield & Gold, 2012), we computed, for both types of services: (1) the fraction of total state expenditures they comprised, and (2) per capita state spending (per woman, age 15–44), with amounts expressed in 2010 constant dollars (US Department of Labor, 2016, Census Bureau, 2016a). We used both measures because research on the political sociology of the welfare state demonstrates both matter: the fraction of state spending aligns with the "welfare effort" conceptualization of the welfare state, and the per capita approach captures the level of public resources that are available to the average person in a state (Clayton & Pontusson, 1998).

So that we could meaningfully compare parameter estimates for these two variables, we modeled each measure as an ordinal categorical variable, ranging from 0 to 4. For the abortion expenditure data, we created a 5-category variable, whereby the lowest category included states which reported $0 funding (ranging from 8 in 1980 to 20 in 2006; mean (standard deviation [SD])=14.0 (3.6)) plus the small number with unreported funding (ranging from 4 in 1987 and 2006 to 9 in 2001; mean (SD)=5.6 (1.7)), and categories 1 to 4 were quartiles based on distribution of funding > $0. We used the same 5 categories for state family planning expenditures, noting however that these expenditures exceeded $0 in all states in all years.

2.2. Outcome data: infant death rates

Using data from the publicly available National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) US compressed mortality file (CMF)(National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a), we computed the infant death rate, defined as: [deaths<age 1]/[population < age 1], in the same calendar year (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a). We used this metric instead of the infant mortality rate ([deaths<age 1]/births, in the same calendar year) to enable results to be compared to other long-term analyses of US infant death rates (including in relation to reproductive policies)(Krieger et al., 2008, Krieger et al., 2015, Krieger et al., 2015; Krieger, Chen, Coull, Waterman & Beckfield, 2013) that extend back to 1960, a period that precedes public availability (starting in 1968) of US data on live births (US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2016, MacDorman et al., 2013). Robust evidence demonstrates the infant death rate and infant mortality rate are very highly correlated (r>0.95) (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a, MacDorman et al., 2013), and both provide an acceptable proxy for the gold-standard infant mortality rate computed using linked data on births and deaths, which are not publicly available until after 1980 (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016b).

The individual-level mortality records and census denominator data, stratified by age, gender, and race/ethnicity, were available aggregated to the county level; counties are the primary legal division of most states and most are functioning governmental units (US Census Bureau, 2016b). We report on the infant death rate lagged by one year after the exposure (state expenditure data), to reflect time elapsed since conception, and note that results were substantively identical to analyses with no lag, as would be expected given relatively little year-to-year variability in our dependent and independent variables.

2.3. Covariates

We included data on nine key state- and county-level sociodemographic and health service covariates identified in the literature as being associated with risk of infant mortality (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, David and Collins, 2014, Finer and Zolna, 2014, Tsui et al., 2010, Singh et al., 2010, Gruskin, 2013, Frost et al., 2015, Grossman and Jacobwitz, 1981, Corman and Grossman, 1985, Joyce, 1987a, Joyce, 1987b, Meier and McFarlane, 1994, McFarlane and Meier, 1998, McFarlane and Meier, 2001, Singh and Kogan, 2007, Sonfield and Gold, 2012, Schreiber and Traxler, 2015) and which could potentially confound or mediate its association with the state expenditures on family planning and abortion services. Using the data sources and methods described below, the state-level covariates comprised: Title X and Medicaid per capita funding, fertility rate, and percent of counties with no abortion services; county-level covariates were: median family income, and percent: black infants, adults with less than a high education, urban, and female labor force participation). Despite technical changes in the precise US census definition of “urban” over time, conceptually the territories included encompass populous and densely settled areas (US Census Bureau, 2016b).

2.4. County income data

The CMF contains no socioeconomic data. We therefore linked the mortality data to county median family income obtained from US census decennial 1980–2010 data (missingness <1%), which we adjusted for inflation and regional cost of living (US Department of Labor, 2016, Krieger et al., 2008). We used linear interpolation for intercensal years and then assigned counties to income quintiles, weighted by county population size, given its enormous variation (Krieger et al., 2008). For 1980–1988, the lack of county data for Alaska required the state׳s data to be analyzed as one county (Krieger et al., 2008).

2.5. Racial/ethnic data

We included data on racial/ethnic composition as a covariate, at the county level, with race/ethnicity conceptualized as a social category arising out of and reinforcing inequitable race relations (Krieger, 2011, Winant, 2000). Warranting its inclusion are well-known racial/ethnic inequities in infant mortality, both within and across socioeconomic levels (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, David and Collins, 2014, Finer and Zolna, 2014). For 1980–2010, the only racial/ethnic categories available in the CMF were “white,” “black,” and “other” populations of color. We were unable to control for individual-level race/ethnicity or to run models stratified by race/ethnicity due to model non-convergence caused by joint distributions that produced many empty cells.

2.6. Additional covariates

At the state-level, to address different funding streams affecting access to reproductive and other health services, we included year-specific data on Title X funding per capita (Sonfield & Gold, 2012) and Medicaid funding per capita (Sonfield & Gold, 2012), and as a marker for need for reproductive health services, we included year-specific data on state fertility rates (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016c). At the county-level, additional census-derived covariates were: percent of adults age 25 and older with less than a high school education; percent urban; and percent female labor force participation (US Census Bureau, 2016c, 2016d; Minnesota Population Center, 2016), and we estimated year-specific data by logistic interpolation between decennial census values. We additionally included, as a potential mediator, state-level data on the percent of counties with no abortion providers (Henshaw & Kost, 2008), and estimated year-specific values by interpolating and extrapolating based on the 1974–2004 data available (Henshaw & Kost, 2008).

2.7. Human subjects protection

Because our analyses solely used publicly available de-identified pre-existing coded data aggregated to the US county level along with county and state-level economic data, our study was exempted from Institutional Review Board review (HSC Protocol #20630-102).

2.8. Statistical analyses

To provide robust tests of our hypotheses, we triangulated (UNAIDS, 2010, Reiss, 2009, Baggaley and Fraser, 2010, Richmond et al., 2014) complementary and appropriate multilevel statistical analyses, each employing Poisson log-linear models (Goldstein, 2011), albeit with different assumptions. Triangulation encompasses using both diverse sources of data and diverse modeling techniques, ideally with uncorrelated biases and errors, with robust results more likely to be unbiased (UNAIDS, 2010, Reiss, 2009, Baggaley and Fraser, 2010, Richmond et al., 2014).

For the first approach, we employed year-specific multilevel Poisson log-linear mixed models with random state and county effects (Goldstein, 2011). These analyses address the question: in any given year, is state funding associated with state infant death rates, controlling for covariates? All models included random state effects (vi) and a randomly-distributed county-level error term (uij), along with the specified covariates. The basic model is as follows:

and where yij and nij represent the number of infant deaths and population size, respectively, observed in county j in state i; additional models added the relevant covariates. For the second approach, we employed a multilevel panel analysis (Goldstein, 2011), using overdispersed Poisson log-linear models with fixed state effects and a dummy variable for year. We also included interactions between year and covariates to allow for temporal changes in covariate effects. This latter approach asks the question: within states, what is the association between changes in state funding and changes in infant death rates, controlling for covariates?

We opted to use both modeling approaches because although panel data treating states as a unit of analysis are often used to analyze policy impacts, including via a difference-in-difference modeling approach, the strong assumption of fixed state effects over time may not necessarily hold (Goldstein, 2011). In our case, preliminary inspection of model results for approach #2 indicated that although some states were fairly consistent in their random effects over time, others were much more variable, thereby rendering problematic an assumption of fixed state effects over time (data available upon request). By using both the random-effects and fixed-effects approaches to unmeasured between-state heterogeneity, however, our analyses effectively control for all unmeasured covariates that do not change over time within states, but nevertheless make states different.

For each approach, we analyzed five models. Model 1 included, as fixed effects, county income quintile and county racial/ethnic composition (percent of population under age 1 categorized as “black”). Building on Model 1, Models 2 through 5 respectively employed our two different approaches to modeling the state expenditure data: per capita (the “a” models) and as fraction of total state expenditures (the “b” models). Model 2 added the state-level expenditure data on family planning and abortion services. Model 3 next added the state-level data on Title X funding per capita, Medicaid funding per capita, and fertility rate. Model 4 then added the county-level data on education, urbanicity, and female labor force participation. Finally, Model 5 added the state-level data on percent of counties with no abortion provider. We fit models in R (R core team, 2014), and assessed model fit using the AIC and BIC diagnostic tests, as implemented by the lme4 package for mixed-effects models (Bates, Maechler, Bolker & Walker S, 2014).

3. Results

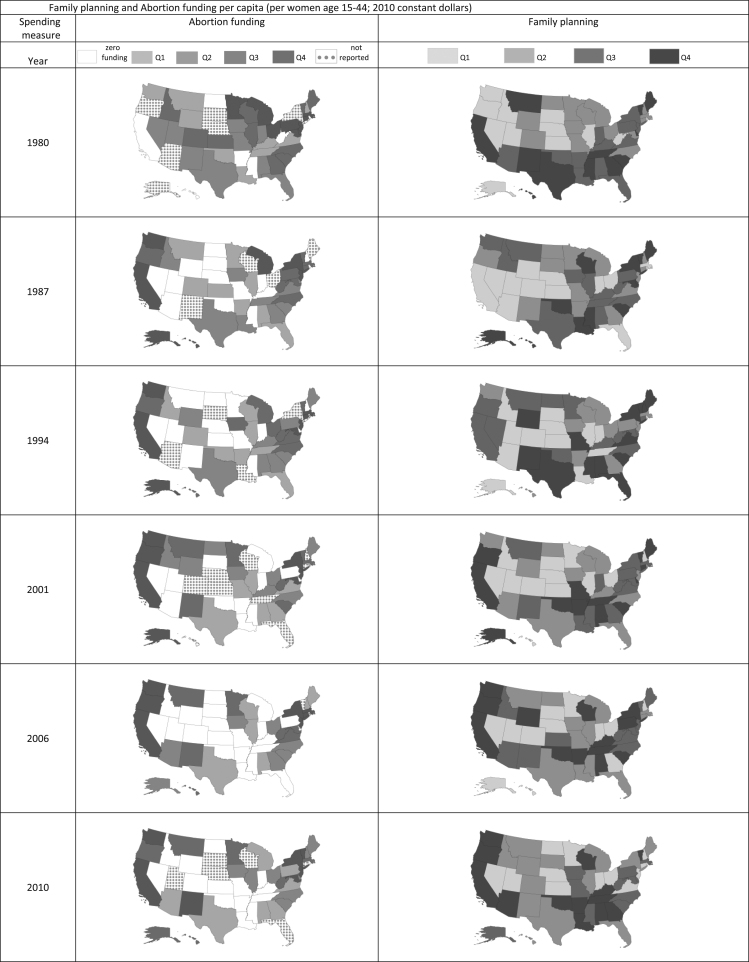

During the study period, the mean US county infant death rate declined by half (1980: 13.2 per 1000 (SD 9.0); 2010: 6.6 (SD 7.5)). Second, regarding the study exposures, between 1980 and 2010, the mean value (in 2010 constant dollars) for state-only per capita funding (per woman, age 15–44) for family planning doubled (1980: $16.2 (SD 5.0); 2010: $33.1 (SD 13.7)), and state variability also increased, as indicated by the near tripling of the SD (Table 1). For state-only abortion funding per capita (per woman, age 15–44), the far smaller values rose then dropped (1980: $0.4 (SD 0.8); 1987: $1.3 (SD 2.5); 2010: $0.8 (SD 1.3)). Similar trends characterized funding as a percent of total state expenditures (Table 1). Fig. 1 in turn displays the state variation in funding, by year; in 2010, state per capita funding (per woman, age 15–44) for family planning ranged from $10.4 to $76.9, and, for abortion, from $0 to $4.6.

Table 1.

US infant death rate, state-only funding for family planning and abortion services, and covariates.

| Variable |

Year |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 1987 | 1994 | 2001 | 2006 | 2010 | |

| Outcome: infant death rate | ||||||

| US county infant death rate (deaths <1 yr/population < 1 yr): mean (SD), per 1000 | 13.2 (9.0) | 9.4 (7.5) | 8.4 (10.1) | 7.2 (8.0) | 7.0 (7.4) | 6.6 (7.5) |

| N of infant deaths (in 1000 s) | 45.5 | 38.4 | 31.7 | 27.6 | 28.5 | 24.6 |

| Person-years at risk (N, in 1000 s) | 3269.7 | 3610.5 | 3837.1 | 4012.7 | 4041.7 | 3944.2 |

| Exposures: state-only expendituresa | ||||||

| Family planningb | ||||||

| $ per capita (women age 15–44): mean (SD) | 16.0 (5.8) | 13.2 (5.0) | 16.2 (6.9) | 22.2 (11.3) | 30.0 (19.7) | 33.1 (13.7) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (6.1; 33.9) | (4.0; 24.7) | (4.6; 34.6) | (6.5; 60.8) | (5.7; 97.4) | (10.4; 76.9) |

| % of state expenditures: mean (SD) | 0.12 (0.05) | 0.09 (0.04) | 0.08 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.11 (0.07) | 0.10 (0.05) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0.02; 0.28) | (0.03; 0.17) | (0.01; 0.17) | (0.02; 0.24) | (0.02; 0.33) | (0.04; 0.24) |

| Abortion services | ||||||

| $ per capita (women age 15–44): mean (SD) | 0.4 (0.8) | 1.3 (2.5) | 1.1 (2.2) | 0.9 (1.8) | 0.8 (1.7) | 0.8 (1.3) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0.0; 4.7) | (0.0; 9.4) | (0.0; 9.2) | (0.0; 6.9) | (0.0; 7.0) | (0.0; 4.6) |

| % of state expenditures: mean (SD) | 0.0033 (0.0051) | 0.0063 (0.0118) | 0.0046 (0.0094) | 0.0032 (0.0063) | 0.0025 (0.0054) | 0.0021 (0.0035) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0.0000; 0.0309) | (0.0000; 0.0441) | (0.0000; 0.0381) | (0.0000; 0.0264) | (0.0000; 0.0251) | (0.0000; 0.0134) |

| Covariates | ||||||

| State | ||||||

| Title X funding per capita: mean (SD) | 0.0089 (0.0033) | 0.0050 (0.0016) | 0.0042 (0.0013) | 0.0046 (0.0017) | 0.0049 (0.0022) | 0.0050 (0.0025) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0.0039; 0.0189) | (0.0025; 0.0086) | (0.0021; 0.0079) | (0.0024; 0.0095) | (0.0019; 0.0139) | (0.0014; 0.0136) |

| Medicaid funding per capita: mean (SD) | 0.0028 (0.0026) | 0.0047 (0.0033) | 0.0078 (0.0054) | 0.01215 (0.0096) | 0.02047 (0.01836) | 0.02339 (0.01317) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0; 0.0105) | (0; 0.0150) | (0; 0.0243) | (0.0009; 0.04193) | (0.0005; 0.08750) | (0.0046; 0.06589) |

| State fertility rate per 1000 | 71.72 (12.44) | 65.98 (7.28) | 63.89 (6.10) | 63.70 (7.10) | 68.41 (8.05) | 69.52 (8.34) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (53.50; 123.00) | (53.50; 92.00) | (52.20; 82.30) | (48.50; 89.70) | (52.20; 94.10) | (52.57; 92.61) |

| State percent of counties with no access to abortion providers | 67.6 (30.0) | 70.6 (29.4) | 73.4 (27.6) | 76.0 (27.3) | 76.3 (26.6) | 76.3 (26.6) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0; 98.7) | (0; 98.1) | (0; 98.0) | (0; 98.3) | (0; 99.0) | (0; 99.0) |

| County | ||||||

| County median family income ($)a: mean (SD) | 39,171 (8,546) | 39,268 (9,402) | 41,480 (9,973) | 43,880 (10,223) | 43,523 (10,238) | 43,231 (10,677) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (16,431; 78,578) | (15,543; 87,102) | (16,562; 92,962) | (15,163; 103,295) | (18,474; 110,657) | (16,290; 116,546) |

| % of county population < age 1 categorized as black: mean (SD) | 10.5 (17.3) | 10.3 (17.0) | 10.7 (17.7) | 10.7 (16.7) | 10.9 (16.5) | 11.5 (16.9) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0; 90.7) | (0; 90.0) | (0; 95.5) | (0; 93.9) | (0; 96.6) | (0; 95.7) |

| Percent adults age 25 and older with less than a high school education: mean (SD) | 40.7 (12.3) | 33.4 (10.9) | 27.1 (9.6) | 21.9 (8.5) | 18.3 (7.61) | 15.9 (7.0) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (4.7; 74.9) | (0.1; 70.0) | (4.2; 67.2) | (3.0; 64.3) | (2.7; 59.3) | (2.5; 55.1) |

| Percent urban: mean (SD) | 11.8 (27.0) | 16.0 (27.8) | 36.3 (29.7) | 39.5 (30.6) | 39.9 (31. 0) | 40.9 (31.1) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (0; 99.9) | (0; 100.0) | (0; 99.9) | (0; 100.0) | (0; 100.0) | (0; 100.0) |

| Percent female labor force participation: mean (SD) | 57.4 (7.9) | 65.6 (7.5) | 69.4 (7.2) | 69.5 (7.2) | 65.7 (7.8) | 62.5 (9.0) |

| (minimum; maximum) | (21.2; 84.3) | (29.2; 87.3) | (35.6; 87.2) | (36.2; 87.6) | (31.2; 88.6) | (15.7; 92.4) |

Note: Sources of expenditure data (Sonfield and Gold, 2012): (1) R.B. Gold, Publicly funded abortions in FY 1980 and FY 1981, Fam Plan Perspec. 14 (1982) 204–207; (2) B. Nestor, Public funding of contraceptive services, 1980–1982, Fam Plan Perspec. 14 (1983) 198–203; (3) R.B. Gold, S. Guardado, Public funding of family planning, sterilization and abortion services, 1987, Fam Plan Perspec. 20 (1988) 228–233; (4) T. Sollom, R.B. Gold, R. Saul, Public funding for contraception, sterilization and abortion services, 1994, Fam Plan Perspec. 28 (1996) 166–173; (5) A. Sonfield, R.B. Gold, Public Funding for Contraceptive, Sterilization and Abortion Services, FY 1980–2001. Guttmacher Institute, New York, 2005; (6) A. Sonfield, C. Alrich, R.B. Gold, Public Funding for Family Planning, Sterilization and Abortion Services, FY 1980–2006. Occasional Report, No. 38. Guttmacher Institute, New York, 2008; (7) A. Sonfield, R.B. Gold, Public Funding for Family Planning, Sterilization and Abortion Services, FY 1980–2010. Guttmacher Institute, New York, 2012

all dollars expressed in 2010 constant dollars.

defined as: “the package of direct patient care services provided through family planning programs to clients receiving reversible contraceptives,” comprising “client counseling and education, contraceptive drugs and devices, related diagnostic tests (e.g., those for pregnancy, Pap, HIV and other STIs) and treatment after diagnosis (e.g., for urinary tract infections and STIs other than HIV)”[16, p. 5].

Fig. 1.

US state-only family planning and abortion funding per capita (per woman, age 15–44), by year.

Additionally, regarding the covariates (Table 1), between 1980 and 2010, the mean of county median family income (in 2010 constant dollars) rose by 10% (1980: $39,171 (SD 8,545); 2010: $43,231 (SD 10,677) and, in any given year, widely varied across counties – for example, in 2010, it ranged from $16,290 to $116,546. By contrast, the mean percent of county population <age 1 categorized as “black” remained around 11% in all years, but in any given year the values across counties spanned from 0% to over 90% (Table 1). The average state value of Title X funding per capita equaled 0.0089 (SD 0.0033) in 1980 and thereafter ranged between 0.0042 and 0.0050. By contrast, the average state value of Medicaid funding per capita increased from 0.0028 (SD 0.0026) in 1980 to 0.02339 (SD 0.01317) in 2010. The average value for state fertility was highest in 1980 and 2010 (approximately 70/1000) and lowest in 1994 and 2001 (approximately 64/1000). At the county level, the average percent of adults age 25 and over with less than a high school education declined from 40.7 (SD 12.3) in 1980 to 15.9 (SD 7.0) in 2010; the average percent urban rose from 11.8 (SD 27.0) in 1980 to 40.9 (SD 31.1) in 2010; and the average percent female labor force participation was lowest in 1980 and 2010 (57% and 62%, respectively) and highest in 1994 and 2001 (approximately 70%). The average state-level percent of counties with no abortion providers was high throughout the study period, and increased from 67.6% (SD 30.0) in 1980 to 76.3% (SD 26.6) in 2010.

Table 2, Table 3 present the multivariate results, respectively, for the repeat cross-sectional and the panel analyses. Since 2000, in all models, an inverse association existed between state funding for abortion services and the infant death rates, with virtually identical results observed for 2001, 2006, and 2010, regardless of analytic approach or method of modeling the expenditure data. Thus, for abortion funding, in models including all covariates (i.e., Table 2, Table 3, Models 5a and 5b), the rate ratio for infant death for a one-unit change in funding quartile for abortion services ranged between 0.94 to 0.98 (95% confidence intervals excluding1, except for the 2001 cross-sectional analysis, whose upper bound equaled 1), yielding an average 15% reduction in risk (i.e., 0.964) (range: 8 to 22%), comparing the top-funding versus no funding categories. For state-only funding for family planning services, an inverse association with infant death rates, robust to analytic approach, was observed only in 1994 for per capita funding, and the reduction of risk of infant death, per a one-unit change in funding quartile, was similarly lower (Table 2, Model 5a: RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.93, 0.96); Table 3 Model 5a: RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.94, 0.98).

Table 2.

Rate ratios for state spending on family planning and abortion services on US infant death ratesa, net of specified county-level sociodemographic and socioeconomic covariates: 1980, 1987, 1994, 2001, 2006, and 2010.b

| Year | Parameter | Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 3a | Model 3b | Model 4a | Model 4b | Model 5a | Model 5b | ||

| 1980 | (intercept: infant deaths per 1000 persons <age 1) | 9.81 (9.38, 10.25) | 10.27 (9.40, 11.23) | 10.28 (9.41, 11.22) | 10.64 (8.62, 13.13) | 10.70 (8.67, 13.20) | 9.97 (7.72, 12.87) | 9.99 (7.73, 12.91) | 9.99 (7.73, 12.92) | 10.04 (7.76, 13.00) |

| County income quintile | ||||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.05, 1.20) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.21) | 1.12 (1.05, 1.20) | 1.12 (1.05, 1.21) | |

| 2 | 1.10 (1.05, 1.15) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.09 (1.04, 1.15) | 1.09 (1.04, 1.15) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.17) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) | |

| 3 | 1.10 (1.05, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | |

| 4 | 1.11 (1.05, 1.17) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.17) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.09 (1.03, 1.16) | |

| 5 (highest; referent group) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| County: % persons < age 1="black" (per 10% increase) | 2.70 (2.46, 2.95) | 2.74 (2.49, 3.01) | 2.74 (2.50, 3.01) | 2.74 (2.49, 3.02) | 2.74 (2.49, 3.01) | 2.32 (2.11, 2.56) | 2.32 (2.10, 2.56) | 2.32 (2.11, 2.56) | 2.32 (2.10, 2.56) | |

| State expenditures on family planning: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | ||||||

| State expenditures on abortion services: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | ||||||

| State Title X funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | ||||

| State Medicaid funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | ||||

| State fertility rate: live births per 1000 women age 15–44 (per change in rate of 10 per 1000) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | ||||

| County: % urban (per 10% increase) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) | ||||||

| County: % less than high school education (per 10% increase) | 1.23 (1.00, 1.51) | 1.21 (0.98, 1.48) | 1.22 (0.99, 1.51) | 1.20 (0.97, 1.48) | ||||||

| County: % female labor force participation | 0.76 (0.59, 0.97) | 0.77 (0.60, 0.98) | 0.76 (0.59, 0.97) | 0.77 (0.60, 0.98) | ||||||

| State: % of counties with no abortion provider | 1.01 (0.93, 1.08) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.09) | ||||||||

| State random effect (standard deviation (SD)) | 0.018 (0.133) | 0.018 (0.135) | 0.018 (0.134) | 0.018 (0.135) | 0.018 (0.134) | 0.019 (0.138) | 0.019 0.138) | 0.019 (0.138) | 0.019 (0.138) | |

| County random effect (SD) | 0.004 (0.060) | 0.003 (0.052) | 0.003 (0.054) | 0.003 0.051) | 0.003 (0.052) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| AIC | 14049.32 | 12932.11 | 12931.55 | 12936.53 | 12935.70 | 12691.36 | 12694.17 | 12693.35 | 12696.06 | |

| BIC | 14097.66 | 12991.63 | 12991.07 | 13013.90 | 13013.07 | 12786.41 | 12789.22 | 12794.34 | 12797.05 | |

| 1987 | (intercept: infant deaths per 1000 persons <age 1) | 7.37 (7.08, 7.68) | 7.49 (6.91, 8.11) | 7.78 (7.16, 8.46) | 6.79 (2.74, 16.81) | 7.15 (2.83, 18.05) | 7.28 (2.55, 20.75) | 7.19 (2.52, 20.51) | 8.00 (2.70, 23.67) | 7.78 (2.63, 23.04) |

| County income quintile | ||||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) | 1.16 (1.11, 1.20) | 1.16 (1.11, 1.21) | 1.17 (1.12, 1.22) | 1.17 (1.12, 1.22) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) | |

| 2 | 1.18 (1.14, 1.23) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.23) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.23) | 1.20 (1.15, 1.24) | 1.20 (1.15, 1.24) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22) | |

| 3 | 1.20 (1.16, 1.25) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.25) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.25) | 1.21 (1.17, 1.26) | 1.21 (1.17, 1.26) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | |

| 4 | 1.14 (1.10, 1.18) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.15 (1.11, 1.19) | 1.15 (1.11, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.10, 1.19) | |

| 5 (highest; referent group) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| County: % persons < age 1="black" (per 10% increase) | 3.87 (3.60, 4.16) | 3.86 (3.59, 4.16) | 3.88 (3.59, 4.19) | 3.88 (3.59, 4.19) | 2.53 (2.27, 2.81) | 2.53 (2.27, 2.81) | 2.53 (2.27, 2.81) | 2.53 (2.27, 2.81) | ||

| State expenditures on family planning: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.08) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.89, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.10) | ||||||

| State expenditures on abortion services: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.10) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.09) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) | 0.99 (0.90, 1.08) | ||||||

| State Title X funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.91, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) | 1.01 (0.91, 1.12) | 1.02 (0.92, 1.13) | 1.01 (0.92, 1.12) | ||||

| State Medicaid funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.09) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.08) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.09) | 0.98 (0.89, 1.09) | ||||

| State fertility rate: live births per 1000 women age 15–44 (per change in rate of 10 per 1000) | 1.01 (0.96, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.95, 1.06) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | ||||

| County: % urban (per 10% increase) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.29) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.29) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.29) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.29) | ||||||

| County: % less than high school education (per 10% increase) | 1.66 (1.33, 2.07) | 1.66 (1.33, 2.07) | 1.65 (1.33, 2.07) | 1.66 (1.33, 2.07) | ||||||

| County: % female labor force participation | 0.86 (0.63, 1.18) | 0.86 (0.63, 1.18) | 0.86 (0.63, 1.18) | 0.86 (0.63, 1.18) | ||||||

| State: % of counties with no abortion provider | 0.87 (0.58, 1.32) | 0.89 (0.58, 1.35) | ||||||||

| State random effect (SD) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| County random effect (SD) | 0.010 (0.098) | 0.008 (0.087) | 0.007 (0.084) | 0.080 0.283) | 0.080 (0.283) | 0.080 (0.283) | 0.080 (0.283) | 0.080 (0.283) | 0.080 (0.283) | |

| AIC | 13006.29 | 12056.05 | 12052.05 | 12114.63 | 12114.14 | 11645.80 | 11645.80 | 11647.38 | 11647.50 | |

| BIC | 13054.64 | 12115.80 | 12111.79 | 12192.29 | 12191.80 | 11741.07 | 11741.08 | 11748.61 | 11748.73 | |

| 1994 | (intercept: infant deaths per 1000 persons <age 1) | 5.40 (5.14, 5.68) | 5.88 (5.51, 6.27) | 5.80 (5.43, 6.20) | 7.98 (6.57, 9.69) | 8.00 (6.58, 9.74) | 6.72 (4.59, 9.83) | 8.86 (2.98, 26.32) | 6.10 (4.10, 9.08) | 7.72 (2.38, 25.05) |

| County income quintile | ||||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.44) | 1.36 (1.29, 1.43) | 1.36 (1.29, 1.44) | 1.36 (1.28, 1.43) | 1.36 (1.29, 1.44) | 1.22 (1.15, 1.31) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.35) | 1.21 (1.13, 1.29) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.35) | |

| 2 | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) | 1.29 (1.22, 1.36) | 1.30 (1.23, 1.37) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.35) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.29) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.31) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.28) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.31) | |

| 3 | 1.20 (1.12, 1.27) | 1.19 (1.12, 1.27) | 1.20 (1.12, 1.27) | 1.19 (1.12, 1.26) | 1.19 (1.12, 1.27) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.16) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.10 (1.06, 1.16) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.18) | |

| 4 | 1.17 (1.11, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.10, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.11, 1.25) | 1.17 (1.10, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.10, 1.24) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.20) | 1.13 (1.08, 1.18) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.20) | |

| 5 (highest; referent group) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| County: % persons < age 1="black" (per 10% increase) | 2.69 (2.43, 2.97) | 2.86 (2.60, 3.14 | 2.87 (2.61, 3.17) | 2.78 (2.52, 3.07) | 2.77 (2.51, 3.06) | 2.85 (2.61, 3.11) | 2.71 (2.41, 3.05) | 2.84 (2.60, 3.10) | 2.71 (2.41, 3.05) | |

| State expenditures on family planning: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.96) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.96) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.88, 1.05) | 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) | ||||||

| State expenditures on abortion services: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.94, 1.06) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.10) | ||||||

| State Title X funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.90, 1.13) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.12) | ||||

| State Medicaid funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.88, 1.11) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.89, 1.12) | ||||

| State fertility rate: live births per 1000 women age 15–44 (per change in rate of 10 per 1000) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | ||||

| County: % urban (per 10% increase) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.18) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.23) | ||||||

| County: % less than high school education (per 10% increase) | 2.00 (1.53, 2.61) | 1.97 (1.47, 2.64) | 2.05 (1.57, 2.67) | 1.98 (1.48, 2.65) | ||||||

| County: % female labor force participation | 1.03 (0.72, 1.48) | 0.85 (0.56, 1.28) | 1.05 (0.73, 1.51) | 0.85 (0.56, 1.29) | ||||||

| State: % of counties with no abortion provider | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) | 1.14 (0.75, 1.73) | ||||||||

| State random effect (SD) | 0.019 (0.136) | 0.021 (0.146) | 0.022 (0.148) | 0.021 (0.144) | 0.021 (0.146) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| County random effect (SD) | 0.004 (0.065) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.080 (0.283) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.080 (0.283) | |

| AIC | 12032.75 | 11432.89 | 11440.93 | 11427.41 | 11432.44 | 11263.56 | 11266.04 | 11262.94 | 11267.67 | |

| BIC | 12081.16 | 11492.90 | 11500.94 | 11505.43 | 11510.46 | 11359.28 | 11361.76 | 11364.66 | 11369.37 | |

| 2001 | (intercept: infant deaths per 1000 persons <age 1) | 4.65 (4.43, 4.88) | 4.99 (4.63, 5.39) | 5.06 (4.67, 5.48) | 6.24 (4.92, 7.89) | 6.54 (5.23, 8.17) | 6.04 (3.57, 10.24) | 6.38 (3.84, 10.61) | 5.54 (3.27, 9.41) | 5.98 (3.59, 9.96) |

| County income quintile | ||||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 1.47 (1.39, 1.56) | 1.41 (1.33, 1.50) | 1.41 (1.33, 1.50) | 1.42 (1.34, 1.51) | 1.42 (1.34, 1.51) | 1.46 (1.34, 1.59) | 1.46 (1.34, 1.59) | 1.43 (1.31, 1.55) | 1.43 (1.31, 1.56) | |

| 2 | 1.40 (1.32, 1.48) | 1.36 (1.27, 1.45) | 1.36 (1.27, 1.45) | 1.36 (1.28, 1.45) | 1.36 (1.28, 1.45) | 1.39 (1.29, 1.49) | 1.39 (1.29, 1.49) | 1.37 (1.27, 1.47) | 1.37 (1.27, 1.47) | |

| 3 | 1.34 (1.25, 1.43) | 1.30 (1.22, 1.39) | 1.30 (1.21, 1.39) | 1.31 (1.22, 1.40) | 1.31 (1.22, 1.40) | 1.33 (1.24, 1.43) | 1.33 (1.24, 1.43) | 1.32 (1.23, 1.41) | 1.32 (1.23, 1.41) | |

| 4 | 1.27 (1.19, 1.35) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.32) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.32) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.32) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | |

| 5 (highest; referent group) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| County: % persons < age 1="black" (per 10% increase) | 2.79 (2.52, 3.08) | 2.63 (2.36, 2.91) | 2.63 (2.37, 2.92) | 2.53 (2.27, 2.82) | 2.53 (2.26, 2.82) | 2.64 (2.34, 2.97) | 2.64 (2.34, 2.98) | 2.58 (2.29, 2.91) | 2.59 (2.30, 2.93) | |

| State expenditures on family planning: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.04) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.03) | ||||||

| State expenditures on abortion services: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | ||||||

| State Title X funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.06) | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | ||||

| State Medicaid funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | ||||

| State fertility rate: live births per 1000 women age 15–44 (per change in rate of 10 per 1000) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | ||||

| County: % urban (per 10% increase) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.12) | 1.03 (0.95, 1.12) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | 1.05 (0.96, 1.14) | ||||||

| County: % less than high school education (per 10% increase) | 0.97 (0.65, 1.43) | 0.97 (0.65, 1.44) | 0.97 (0.65, 1.43) | 0.96 (0.65, 1.43) | ||||||

| County: % female labor force participation | 1.06 (0.65, 1.71) | 1.04 (0.64, 1.67) | 0.96 (0.59, 1.55) | 0.94 (0.58, 1.53) | ||||||

| State: % of counties with no abortion provider | 1.21 (1.07, 1.37) | 1.19 (1.05, 1.35) | ||||||||

| State random effect (SD) | 0.031 (0.176) | 0.028 (0.168) | 0.028 (0.167) | 0.027 (0.164) | 0.027 (0.163) | 0.023 (0.151) | 0.023 (0.150) | 0.023 (0.151) | 0.023 (0.150) | |

| County random effect (SD) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| AIC | 12006.38 | 10184.33 | 10182.90 | 10181.45 | 10179.21 | 9973.99 | 9972.15 | 9966.80 | 9966.77 | |

| BIC | 12054.79 | 10243.03 | 10241.60 | 10257.76 | 10255.52 | 10067.69 | 10065.86 | 10066.36 | 10066.33 | |

| 2006 | (intercept: infant deaths per 1000 persons <age 1) | 4.90 (4.64, 5.18) | 5.07 (4.67, 5.51) | 4.92 (4.53, 5.35) | 5.28 (3.72, 7.50) | 5.60 (4.47, 7.01) | 4.54 (2.86, 7.20) | 4.74 (3.04, 7.37) | 4.52 (2.85, 7.18) | 4.76 (3.06, 7.41) |

| County income quintile | ||||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.45) | 1.36 (1.28, 1.44) | 1.35 (1.27, 1.43) | 1.35 (1.28, 1.44) | 1.34 (1.27, 1.42) | 1.33 (1.23, 1.44) | 1.33 (1.23, 1.44) | 1.32 (1.22, 1.43) | 1.32 (1.22, 1.43) | |

| 2 | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) | 1.27 (1.19, 1.35) | 1.27 (1.19, 1.35) | 1.27 (1.19, 1.35) | 1.26 (1.19, 1.34) | 1.26 (1.18, 1.35) | 1.26 (1.18, 1.35) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.34) | 1.26 (1.18, 1.34) | |

| 3 | 1.25 (1.17, 1.33) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.16, 1.32) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) | 1.21 (1.14, 1.30) | 1.22 (1.14, 1.30) | 1.21 (1.13, 1.29) | 1.22 (1.14, 1.30) | |

| 4 | 1.18 (1.11, 1.26) | 1.17 (1.10, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.10, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.10, 1.24) | 1.16 (1.09, 1.23) | 1.16 (1.09, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.24) | 1.16 (1.09, 1.23) | 1.16 (1.09, 1.24) | |

| 5 (highest; referent group) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |

| County: % persons < age 1="black" (per 10% increase) | 2.68 (2.40, 2.99) | 2.64 (2.38, 2.94) | 2.65 (2.38, 2.94) | 2.66 (2.38, 2.96) | 2.67 (2.42, 2.94) | 2.66 (2.39, 2.96) | 2.65 (2.38, 2.95) | 2.64 (2.37, 2.94) | 2.63 (2.35, 2.93) | |

| State expenditures on family planning: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.07) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | ||||||

| State expenditures on abortion services: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | ||||||

| State Title X funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | ||||

| State Medicaid funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.99 (0.95, 1.04) | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | ||||

| State fertility rate: live births per 1000 women age 15–44 (per change in rate of 10 per 1000) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | ||||

| County: % urban (per 10% increase) | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.13) | 1.05 (0.97, 1.14) | ||||||

| County: % less than high school education (per 10% increase) | 1.64 (1.11, 2.43) | 1.60 (1.08, 2.37) | 1.65 (1.11, 2.44) | 1.61 (1.09, 2.38) | ||||||

| County: % female labor force participation | 1.27 (0.84, 1.92) | 1.27 (0.84, 1.91) | 1.22 (0.80, 1.87) | 1.22 (0.80, 1.86) | ||||||

| State: % of counties with no abortion provider | 1.06 (0.93, 1.19) | 1.05 (0.93, 1.19) | ||||||||

| State random effect (SD) | 0.024 (0.156) | 0.024 (0.155) | 0.024 (0.155) | 0.024 (0.154) | 0.027 (0.165) | 0.024 (0.156) | 0.024 (0.155) | 0.024 (0.156) | 0.024 (0.155) | |

| County random effect (SD) | 0.007 (0.084) | 0.004 (0.065) | 0.004 (0.061) | 0.004 (0.065) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| AIC | 12206.57 | 12088.69 | 12086.52 | 12094.02 | 12101.03 | 11883.03 | 11876.43 | 11884.31 | 11877.82 | |

| BIC | 12254.98 | 12149.12 | 12146.95 | 12172.58 | 12179.59 | 11979.53 | 11972.93 | 11986.85 | 11980.35 | |

| 2010 | (intercept: infant deaths per 1000 persons <age 1) | 4.33 (4.08, 4.59) | 4.93 (4.57, 5.31) | 5.02 (4.65, 5.41) | 7.50 (5.70, 9.87) | 7.51 (5.70, 9.90) | 10.36 (6.64, 16.17) | 10.24 (6.62, 15.86) | 10.39 (6.64, 16.24) | 10.31 (6.66, 15.98) |

| County income quintile | ||||||||||

| 1 (lowest) | 1.45 (1.36, 1.54) | 1.43 (1.34, 1.53) | 1.42 (1.33, 1.52) | 1.44 (1.35, 1.54) | 1.43 (1.34, 1.53) | 1.37 (1.26, 1.50) | 1.36 (1.24, 1.48) | 1.37 (1.26, 1.51) | 1.36 (1.25, 1.49) | |

| 2 | 1.32 (1.24, 1.41) | 1.29 (1.21, 1.38) | 1.28 (1.20, 1.37) | 1.30 (1.22, 1.40) | 1.29 (1.21, 1.38) | 1.27 (1.18, 1.36) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.35) | 1.27 (1.17, 1.37) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.36) | |

| 3 | 1.29 (1.21, 1.39) | 1.28 (1.19, 1.38) | 1.26 (1.18, 1.36) | 1.27 (1.19, 1.37) | 1.27 (1.18, 1.36) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.36) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.34) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.36) | 1.25 (1.16, 1.35) | |

| 4 | 1.16 (1.08, 1.24) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.15 (1.07, 1.23) | 1.15 (1.07, 1.23) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.13 (1.06, 1.21) | 1.14 (1.06, 1.22) | 1.13 (1.06, 1.21) | |

| 5 (highest; referent group) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | 1.0 (ref) | |||||

| County: % persons < age 1="black" (per 10% increase) | 2.19 (1.94, 2.47) | 2.27 (2.03, 2.54) | 2.30 (2.06, 2.56) | 2.22 (1.99, 2.49) | 2.26 (2.02, 2.52) | 2.35 (2.09, 2.65) | 2.37 (2.11, 2.67) | 2.36 (2.08, 2.66) | 2.39 (2.12, 2.70) | |

| State expenditures on family planning: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | ||||||

| State expenditures on abortion services: | ||||||||||

| per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | ||||||

| fraction of total state expenditures (categories: 0-4c) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.95 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | ||||||

| State Title X funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | ||||

| State Medicaid funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.93, 1.00) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.94, 1.01) | ||||

| State fertility rate: live births per 1000 women age 15–44 (per change in rate of 10 per 1000) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | ||||

| County: % urban (per 10% increase) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) | 0.92 (0.84, 1.00) | 0.91 (0.84, 1.00) | ||||||

| County: % less than high school education (per 10% increase) | 0.89 (0.58, 1.38) | 0.92 (0.59, 1.42) | 0.89 (0.57, 1.39) | 0.90 (0.58, 1.41) | ||||||

| County: % female labor force participation | 0.71 (0.47, 1.08) | 0.71 (0.47, 1.07) | 0.72 (0.47, 1.08) | 0.72 (0.48, 1.09) | ||||||

| State: % of counties with no abortion provider | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) | 0.97 (0.85, 1.11) | ||||||||

| State random effect (SD) | 0.030 (0.172) | 0.033 (0.182) | 0.032 (0.179) | 0.033 (0.181) | 0.032 (0.178) | 0.027 (0.165) | 0.026 (0.162) | 0.027 (0.165) | 0.026 (0.162) | |

| County random effect (SD) | 0.007 (0.081) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | 0.000 (0.000) | |

| AIC | 11402.75 | 10341.75 | 10323.14 | 10333.45 | 10318.33 | 10149.36 | 10142.14 | 10151.34 | 10143.89 | |

| BIC | 11451.15 | 10401.12 | 10382.51 | 10410.64 | 10395.51 | 10244.18 | 10236.96 | 10252.09 | 10244.63 | |

Based on year-specific Poisson loglinear mixed models with state and county random effects. All infant death rates are lagged by one year.

all dollars expressed in 2010 constant dollars

categories: 0=either $0 or funding not reported; 1 to 4=quartiles based on distribution of funding >$0

Table 3.

Panel analysisa: state family planning and abortion services expendituresb and US infant death rates (1980–2010).

| Rate ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2a | Model 2b | Model 3a | Model 3b | Model 4a | Model 4b | Model 5a | Model 5b | |

| Intercept: infant deaths per 1000 persons <age 1 | 12.33 (11.13, 13.66) | 11.61 (10.19, 13.24) | 11.54 (10.12, 13.14) | 7.98 (6.29, 10.14) | 9.31 (7.26, 11.95) | 8.36 (6.01, 11.63) | |||

| Year | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1980 | 0.77 (0.74, 0.81) | 0.76 (0.70, 0.82) | 0.76 (0.70, 0.82) | 0.90 (0.72, 1.12) | 0.87 (0.70, 1.08) | 0.84 (0.56, 1.26) | 0.74 (0.50, 1.11) | 0.83 (0.55, 1.26) | 0.74 (0.49, 1.11) |

| 1987 | 0.54 (0.52, 0.56) | 0.59 (0.55, 0.64) | 0.58 (0.53, 0.63) | 0.78 (0.63, 0.96) | 0.74 (0.60, 0.92) | 0.73 (0.45, 1.20) | 0.71 (0.43, 1.16) | 0.69 (0.41, 1.14) | 0.63 (0.38, 1.05) |

| 1994 | 0.46 (0.44, 0.49) | 0.51 (0.47, 0.55) | 0.51 (0.46, 0.56) | 0.68 (0.53, 0.86) | 0.74 (0.59, 0.93) | 0.71 (0.41, 1.22) | 0.73 (0.43, 1.24) | 0.69 (0.40, 1.19) | 0.71 (0.42, 1.22) |

| 2001 | 0.48 (0.46, 0.50) | 0.52 (0.48, 0.57) | 0.50 (0.46, 0.54) | 0.55 (0.43, 0.70) | 0.60 (0.47, 0.76) | 0.55 (0.34, 0.89) | 0.60 (0.38, 0.96) | 0.55 (0.34, 0.89) | 0.59 (0.37, 0.94) |

| 2006 | 0.42 (0.40, 0.44) | 0.49 (0.45, 0.54) | 0.49 (0.45, 0.54) | 0.71 (0.54, 0.93) | 0.75 (0.56, 0.98) | 1.16 (0.72, 1.86) | 1.14 (0.71, 1.81) | 1.14 (0.71, 1.84) | 1.11 (0.69, 1.77) |

| 2010 | |||||||||

| County % persons<age1="black" (per 10% increase) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 2.82 (2.63, 3.01) | 2.80 (2.61, 3.01) | 2.80 (2.61, 3.00) | 2.87 (2.67, 3.08) | 2.88 (2.68, 3.09) | 2.38 (2.18, 2.61) | 2.39 (2.18, 2.62) | 2.39 (2.18, 2.62) | 2.38 (2.18, 2.61) |

| 1987 | 3.78 (3.52, 4.05) | 3.81 (3.54, 4.10) | 3.74 (3.47, 4.03) | 3.79 (3.51, 4.08) | 3.77 (3.50, 4.06) | 2.83 (2.56, 3.12) | 2.80 (2.54, 3.09) | 2.83 (2.57, 3.13) | 2.80 (2.54, 3.08) |

| 1994 | 3.00 (2.78, 3.24) | 3.05 (2.81, 3.31) | 3.08 (2.84, 3.34) | 3.05 (2.80, 3.32) | 3.05 (2.80, 3.32) | 2.83 (2.55, 3.14) | 2.89 (2.60, 3.21) | 2.84 (2.56, 3.15) | 2.90 (2.61, 3.22) |

| 2001 | 2.97 (2.74, 3.23) | 2.79 (2.56, 3.05) | 2.78 (2.54, 3.03) | 2.63 (2.40, 2.89) | 2.60 (2.37, 2.85) | 2.94 (2.64, 3.28) | 2.93 (2.63, 3.27) | 2.90 (2.60, 3.24) | 2.89 (2.59, 3.23) |

| 2006 | 2.92 (2.70, 3.17) | 2.81 (2.59, 3.05) | 2.84 (2.62, 3.09) | 2.88 (2.64, 3.13) | 2.86 (2.63, 3.11) | 2.98 (2.70, 3.28) | 2.94 (2.67, 3.25) | 2.97 (2.69, 3.28) | 2.94 (2.66, 3.24) |

| 2010 | 2.50 (2.28, 2.75) | 2.47 (2.25, 2.71) | 2.50 (2.27, 2.75) | 2.42 (2.20, 2.67) | 2.47 (2.24, 2.73) | 2.69 (2.41, 3.00) | 2.69 (2.42, 3.00) | 2.71 (2.42, 3.03) | 2.75 (2.46, 3.08) |

| County income quintile 1 (relative to quintile 5) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.09 (1.05, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.17) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.16) | 1.10 (1.04, 1.17) | 1.10 (1.03, 1.17) |

| 1987 | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.16 (1.11, 1.21) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.25) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.26) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.26) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.26) |

| 1994 | 1.31 (1.25, 1.37) | 1.35 (1.29, 1.41) | 1.35 (1.29, 1.41) | 1.37 (1.30, 1.43) | 1.36 (1.30, 1.42) | 1.27 (1.18, 1.37) | 1.27 (1.18, 1.37) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.36) | 1.26 (1.16, 1.36) |

| 2001 | 1.37 (1.31, 1.44) | 1.34 (1.27, 1.41) | 1.35 (1.28, 1.42) | 1.35 (1.29, 1.42) | 1.36 (1.29, 1.43) | 1.44 (1.33, 1.55) | 1.44 (1.34, 1.56) | 1.43 (1.32, 1.54) | 1.44 (1.33, 1.55) |

| 2006 | 1.35 (1.29, 1.41) | 1.31 (1.25, 1.37) | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.29 (1.20, 1.38) | 1.29 (1.20, 1.38) | 1.29 (1.20, 1.39) | 1.29 (1.20, 1.38) |

| 2010 | 1.36 (1.29, 1.43) | 1.32 (1.25, 1.39) | 1.31 (1.24, 1.38) | 1.32 (1.25, 1.40) | 1.32 (1.25, 1.39) | 1.28 (1.19, 1.39) | 1.26 (1.17, 1.37) | 1.30 (1.20, 1.41) | 1.29 (1.19, 1.40) |

| County income quintile 2 (relative to quintile 5) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.07 (1.03, 1.11) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.14) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) |

| 1987 | 1.13 (1.08, 1.17) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.22) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.23) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.23) |

| 1994 | 1.26 (1.20, 1.32) | 1.29 (1.23, 1.35) | 1.29 (1.23, 1.35) | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.25 (1.18, 1.32) | 1.26 (1.19, 1.33) | 1.25 (1.18, 1.32) | 1.25 (1.18, 1.32) |

| 2001 | 1.36 (1.30, 1.42) | 1.32 (1.26, 1.39) | 1.33 (1.26, 1.40) | 1.33 (1.27, 1.40) | 1.34 (1.28, 1.41) | 1.38 (1.30, 1.46) | 1.38 (1.30, 1.46) | 1.37 (1.29, 1.45) | 1.38 (1.30, 1.46) |

| 2006 | 1.30 (1.24, 1.36) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.31) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.30) | 1.24 (1.19, 1.31) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.30) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.31) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.31) | 1.25 (1.18, 1.32) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.31) |

| 2010 | 1.32 (1.25, 1.38) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.31) | 1.23 (1.16, 1.29) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.31) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.31) | 1.22 (1.15, 1.30) | 1.21 (1.13, 1.28) | 1.23 (1.16, 1.32) | 1.23 (1.15, 1.31) |

| County income quintile 3 (relative to quintile 5) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.12) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.12) | 1.07 (1.03, 1.12) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) | 1.08 (1.04, 1.13) |

| 1987 | 1.14 (1.09, 1.18) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.26) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.26) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.26) | 1.21 (1.16, 1.26) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) |

| 1994 | 1.17 (1.12, 1.22) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.19 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.25) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.24) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.13 (1.08, 1.19) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.18) |

| 2001 | 1.29 (1.23, 1.35) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.31) | 1.25 (1.19, 1.32) | 1.27 (1.21, 1.34) | 1.28 (1.21, 1.35) | 1.32 (1.25, 1.40) | 1.33 (1.25, 1.40) | 1.32 (1.24, 1.39) | 1.32 (1.25, 1.40) |

| 2006 | 1.21 (1.15, 1.26) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.12, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) |

| 2010 | 1.24 (1.18, 1.30) | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.20 (1.14, 1.26) | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27) | 1.21 (1.14, 1.27) | 1.20 (1.13, 1.27) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.25) | 1.21 (1.14, 1.28) | 1.20 (1.13, 1.27) |

| County income quintile 4 (relative to quintile 5) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.12 (1.08, 1.16) | 1.12 (1.08, 1.17) | 1.12 (1.07, 1.16) | 1.11 (1.07, 1.16) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.15) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.15) | 1.10 (1.06, 1.15) | 1.11 (1.06, 1.15) | 1.10 (1.06, 1.15) |

| 1987 | 1.14 (1.09, 1.18) | 1.15 (1.11, 1.20) | 1.16 (1.12, 1.21) | 1.15 (1.11, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) |

| 1994 | 1.18 (1.13, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.18 (1.13, 1.24) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.21) | 1.15 (1.10, 1.21) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.20) | 1.15 (1.09, 1.20) |

| 2001 | 1.26 (1.20, 1.32) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.28) | 1.22 (1.16, 1.28) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.30) | 1.23 (1.17, 1.30) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.31) | 1.24 (1.18, 1.31) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.30) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.30) |

| 2006 | 1.18 (1.12, 1.23) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.21) | 1.16 (1.11, 1.21) | 1.16 (1.10, 1.21) | 1.17 (1.11, 1.22) | 1.17 (1.12, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) | 1.17 (1.12, 1.23) | 1.18 (1.12, 1.24) |

| 2010 | 1.15 (1.09, 1.21) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 1.12 (1.06, 1.18) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.08, 1.20) | 1.13 (1.07, 1.20) |

| State-only expenditures on family planning: per capita (women age 15–44) (categories 0–4b) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | |||||

| 1987 | 0.98 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | |||||

| 1994 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | |||||

| 2001 | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | |||||

| 2006 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | |||||

| 2010 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | |||||

| State-only expenditures on family planning: fraction of total state expenditures (categories 0–4b) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | |||||

| 1987 | 0.98 (0.97, 0.99) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | |||||

| 1994 | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.98) | |||||

| 2001 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.05) | |||||

| 2006 | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 1.06 (1.04, 1.09) | 1.05 (1.02, 1.07) | 1.04 (1.02, 1.06) | |||||

| 2010 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | |||||

| State-only expenditures on abortion: per capita (women age 15–44) (categories 0–4b) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | |||||

| 1987 | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.03 (1.01, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | |||||

| 1994 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | |||||

| 2001 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.95 (0.94, 0.96) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | |||||

| 2006 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | |||||

| 2010 | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.96) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.95 (0.93, 0.97) | |||||

| State-only expenditures on abortion: fraction of total state expenditures (categories 0–4b) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 0.99 (0.98, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | |||||

| 1987 | 1.03 (1.02, 1.04) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | |||||

| 1994 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | |||||

| 2001 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | |||||

| 2006 | 0.96 (0.95, 0.97) | 0.95 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.96 (0.95, 0.98) | |||||

| 2010 | 0.95 (0.94, 0.96) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.96) | 0.95 (0.94, 0.97) | 0.94 (0.93, 0.96) | |||||

| State Title X funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0-4c) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.02) | |||

| 1987 | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.98, 1.05) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | |||

| 1994 | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | |||

| 2001 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | |||

| 2006 | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.01) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00) | |||

| 2010 | 1.03 (1.00, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.97, 1.05) | 1.02 (0.99, 1.06) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.04) | 1.02 (0.98, 1.05) | 0.99 (0.96, 1.03) | |||

| State Medicaid funding per capita (women age 15–44) (categories: 0–4) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | |||

| 1987 | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.99) | 0.97 (0.95, 0.98) | |||

| 1994 | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.97, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | |||

| 2001 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.95) | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | |||

| 2006 | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.94 (0.92, 0.97) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.98 (0.95, 1.00) | 0.96 (0.94, 0.99) | |||

| 2010 | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) | 0.93 (0.90, 0.96) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.93, 0.99) | 0.96 (0.93, 1.00) | 0.97 (0.94, 1.01) | |||

| State fertility rate: live births per 1000 women age 15–44 (per change in rate of 10 per 1000) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.02) | 1.02 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | |||

| 1987 | 1.01 (1.00, 1.03) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | |||

| 1994 | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | |||

| 2001 | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | |||

| 2006 | 1.02 (1.01, 1.04) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.99, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.01) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | |||

| 2010 | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.98 (0.97, 1.00) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) | |||

| County Percent Urban (per 10% change) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.15 (1.10, 1.20) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | 1.14 (1.09, 1.19) | |||||

| 1987 | 1.19 (1.13, 1.25) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.25) | 1.19 (1.13, 1.25) | 1.19 (1.14, 1.25) | |||||

| 1994 | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | 1.10 (1.02, 1.19) | |||||

| 2001 | 0.98 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.98 (0.91, 1.07) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.08) | 0.99 (0.92, 1.08) | |||||

| 2006 | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) | |||||

| 2010 | 0.89 (0.82, 0.96) | 0.89 (0.82, 0.96) | 0.88 (0.81, 0.96) | 0.87 (0.81, 0.95) | |||||

| County Percent Less Than High School Education (per 10% change) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.35 (1.11, 1.64) | 1.34 (1.11, 1.63) | 1.36 (1.11, 1.65) | 1.35 (1.11, 1.64) | |||||

| 1987 | 1.71 (1.35, 2.15) | 1.74 (1.38, 2.19) | 1.71 (1.35, 2.15) | 1.73 (1.37, 2.18) | |||||

| 1994 | 1.97 (1.46, 2.67) | 1.98 (1.47, 2.69) | 2.00 (1.48, 2.72) | 2.04 (1.51, 2.77) | |||||

| 2001 | 0.85 (0.59, 1.22) | 0.85 (0.59, 1.22) | 0.85 (0.59, 1.23) | 0.84 (0.58, 1.21) | |||||

| 2006 | 1.57 (1.10, 2.24) | 1.58 (1.11, 2.24) | 1.57 (1.10, 2.23) | 1.57 (1.10, 2.24) | |||||

| 2010 | 1.06 (0.71, 1.57) | 1.12 (0.75, 1.66) | 1.01 (0.68, 1.51) | 1.05 (0.70, 1.56) | |||||

| County Percent Female Labor Force Participation (per 10% change) | |||||||||

| 1980 | 0.86 (0.67, 1.09) | 0.83 (0.65, 1.06) | 0.87 (0.68, 1.11) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.09) | |||||

| 1987 | 1.12 (0.82, 1.52) | 1.15 (0.85, 1.56) | 1.14 (0.84, 1.55) | 1.16 (0.86, 1.58) | |||||

| 1994 | 1.11 (0.73, 1.67) | 1.10 (0.73, 1.67) | 1.13 (0.75, 1.71) | 1.14 (0.75, 1.72) | |||||

| 2001 | 1.15 (0.72, 1.83) | 1.15 (0.72, 1.84) | 1.08 (0.68, 1.74) | 1.08 (0.67, 1.73) | |||||

| 2006 | 1.24 (0.83, 1.86) | 1.20 (0.80, 1.78) | 1.23 (0.82, 1.85) | 1.19 (0.79, 1.79) | |||||

| 2010 | 0.75 (0.50, 1.11) | 0.73 (0.49, 1.08) | 0.77 (0.51, 1.15) | 0.77 (0.52, 1.15) | |||||

| State Percent of Counties with No Abortion Provider | |||||||||

| 1980 | 1.08 (0.94, 1.23) | 1.10 (0.96, 1.27) | |||||||

| 1987 | 1.09 (0.93, 1.27) | 1.12 (0.95, 1.31) | |||||||

| 1994 | 1.15 (0.97, 1.36) | 1.21 (1.02, 1.44) | |||||||

| 2001 | 1.19 (1.00, 1.43) | 1.21 (1.01, 1.45) | |||||||

| 2006 | 1.10 (0.92, 1.32) | 1.11 (0.93, 1.32) | |||||||

| 2010 | 1.02 (0.86, 1.22) | 1.00 (0.84, 1.18) | |||||||

| Overdispersion parameter | 1.304377 | 1.277615399 | 1.276587305 | 1.27027751 | 1.26779766 | 1.232979544 | 1.231788362 | 1.23298756 | 1.231407699 |

| Residual deviance | 24662.73469 | 22400.66622 | 22381.31827 | 22277.60526 | 22248.41626 | 21345.10392 | 21328.71126 | 21337.89213 | 21316.4696 |

Based on overdispersed Poisson loglinear models with state fixed effects. All infant death rates are lagged by one year.

categories: 0=either $0 or funding not reported; 1 to 4=quartiles based on distribution of funding >$0.

Two additional findings robust to analytic approach pertained to increased risk associated with county lower income and higher proportion of black infants. For county income, the inverse association increased over time, e.g., the RR comparing the lowest to highest county income quintile in 1980 equaled 1.12 (95% CI 1.07, 1.18) in the year-specific analysis (Table 2, Model 1) and 1.09 (95% CI 1.05, 1.13) in the panel analysis (Table 3, Model 1); in 2010, these RRs equaled, respectively, 1.45 (95% CI 1.36, 1.54) and 1.36 (95% CI 1.29, 1.43). For race/ethnicity, the excess risk associated with a 10% increase in the county percent of black infants rose from 1980 to 1987 and then modestly declined, with values for 2010 on par with those for 1980. Thus, in the repeat cross-sectional analysis (Table 2, Model 1), the RR rose from 2.70 in 1980 (95% CI 2.46, 2.95) to 3.86 in 1987 (95% CI 3.60, 4.16) and declined to 2.19 in 2010 (95% CI 1.94, 2.47); the analogous RR for the panel analysis (Table 3, Model 1) were 2.82 (95% CI 2.63, 3.01), 3.78 (95% CI 3.52, 4.05), and 2.50 (95% CI 2.28, 2.75).

4. Discussion

Our analysis of US county infant death rates during the 1980–2010 period provides robust new evidence that, since 2000, state-only expenditures on abortion services have become inversely associated with risk of infant death. Additionally, between 1980 and 2010, the socioeconomic gradient for infant death steepened and the excess risk observed in counties with a high proportion of black infants persisted in all years. Inverse associations between state-only funding for family planning and risk of infant death, however, were observed only in 1994.

Before interpreting these results, it is important to consider study limitations. An ideal data set would have: (a) employed 1960–2010 US national annual individual-level data on infant deaths linked to live births, in records containing socioeconomic data and other relevant covariates (e.g., maternal age, intended vs. unintended pregnancy, gestational length, maternal residence in the year prior to and including the birth and death of the infant, and access to both public and private health insurance); (b) nested these records within counties (and hence states), and (c) linked them to detailed annual high-quality data on (i) federal, state, county, and private charitable expenditures on family planning and abortion services and other maternal and child health services, including those focused on reducing postnatal mortality, as utilized by state residents and non-residents, and (ii) state-level data on abortion rates and unintended pregnancy rates. No such linked data sets exist (Finer and Zolna, 2014, Singh and Kogan, 2007, Sonfield and Gold, 2012, National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a, National Center for Health Statistics, 2016b, Guttmacher Institute, 2016, Pazol et al., 2013, Mosher et al., 2012).

Our alternative approach thus entailed using the best measured exposure data (Sonfield & Gold, 2012), in conjunction with the corresponding national mortality data (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a), additionally linked to relevant state- and county-level covariates (Krieger et al., 2008, National Center for Health Statistics, 2016c, Census Bureau, 2016c, Census Bureau, 2016, Minnesota Population Center, 2016, Henshaw and Kost, 2008). Suggesting our approach is reasonable, the infant death rate, as noted above, is highly correlated with the infant mortality rate (National Center for Health Statistics, 2016a, MacDorman et al., 2013). Socioeconomic gradients in infant mortality rates and their trends detected using county-level economic data (Krieger et al., 2008, Blumenshine et al., 2010) are similar to those observed using individual- and household-level economic data (Blumenshine et al., 2010). Our approach also takes into account documented high correlations between the social indicator of county racial/ethnic composition (% black, for persons < age 1) and geographic variation in US infant mortality rates (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, David and Collins, 2014, Singh and Kogan, 2007, Christopher and Simpson, 2014), and also documented high correlations in rates of abortion in relation to women׳s state of residence and the state in which the abortion occurred (Guttmacher Institute, 2016, Pazol et al., 2013). Additional potential data limitations, moreover, would likely lead to conservative, not inflated, effect estimates, including: (1) measurement error regarding funding levels (especially since no evidence indicates any systematic bias in relation to state, time, or funding source (Sonfield & Gold, 2012)); (2) women׳s travel to other states to have abortions; (3) including the handful of states not reporting funding with the two-fold larger number of states reporting $0 funding; and (4) lack of data on alternative sources of abortion funding (e.g., charitable donations).

Drawing on methods employed from political sociology (Clayton & Pontusson, 1998), our study innovatively modeled the state-only family planning and abortion service expenditures both in per capita terms (per woman, age 15–44) and as fraction of total state spending. An additional strength is that our exposure variable (actual state funding) avoids reliance on defining exposures in relation to laws that may or may not be implemented or enforced (Winter, 2012, Cole and Fielding, 2007) and, given the time period examined, also avoids complications of comparisons before and after passage of the Affordable Care Act (SACIM, 2016).

Furthermore, in contrast to the handful of prior analyses of US state reproductive health funding and birth outcomes (Grossman and Jacobwitz, 1981, Corman and Grossman, 1985, Joyce, 1987a, Joyce, 1987b, Meier and McFarlane, 1994, McFarlane and Meier, 1998, McFarlane and Meier, 2001), we employed two complementary multilevel statistical approaches (Goldstein, 2011), each premised on different statistical assumptions, which allowed us to examine (controlling for the same covariates) both: (a) the year-specific exposure-outcome associations across states (with random state effects), and (b) the associations within states (with state fixed effects) over time. By triangulating (UNAIDS, 2010, Reiss, 2009, Baggaley and Fraser, 2010, Richmond et al., 2014) these different analytic approaches and different methods of modeling the exposure variable, each with their different assumptions, we were able to identify associations robust to analytic and modeling approach. The similarity of our findings to those of the earlier studies (Grossman and Jacobwitz, 1981, Corman and Grossman, 1985, Joyce, 1987a, Joyce, 1987b, Meier and McFarlane, 1994, McFarlane and Meier, 1998, McFarlane and Meier, 2001) is especially noteworthy because the time periods analyzed by these earlier studies (i.e., 1970–1972 (Grossman & Jacobwitz, 1981), 1969–1978 (Corman & Grossman, 1985), 1976–1978 (Joyce, 1987a), and 1982–1998 (Meier & McFarlane, 1994; McFarlane & Meier, 1998,2001)) differed with respect to available contraceptive technologies and laws regulating access to both contraception and abortion (Frost et al., 2015, Schreiber and Traxler, 2015).

One plausible explanation for why an inverse association between state-only expenditures and infant death rates occurred for family planning services prior to 2000 (in 1994) and for abortion services after 2000 (for 2001, 2006, and 2010) involves changing patterns of access to and use of these publicly funded reproductive health services (Frost et al., 2015, McFarlane and Meier, 2001, Schreiber and Traxler, 2015, Kost, 2015, Jones and Kavanaugh., 2011, Jacobs and Stanfors, 2015). In particular, the use of abortion services in the US has become increasingly concentrated among low-income women of color (Jones and Kavanaugh., 2011, Jacobs and Stanfors, 2015, Guttmacher Institute, 2016), far more so than use of contraceptives (whether or not publicly funded) (Frost et al., 2015, Jones et al., 2012, Frost et al., 2010, MacDorman et al., 2013, Guttmacher Institute, 2016). Because deficiencies in policies and resources render infants born impoverished at the highest risk for infant mortality (Report of the Secretary׳s Advisory Committee on Infant Mortality (SACIM), 2016, David and Collins, 2014, Singh and Kogan, 2007, Krieger et al., 2008, Blumenshine et al., 2010, Christopher and Simpson, 2014), it logically follows that infant deaths would be more sensitive (in relative terms) to reductions in public funding for abortion services as compared to contraceptive services. Our finding that parameter estimates were robust to inclusion of state-level data on percent of counties with no abortion services likely reflects the high value of this percentage over time (on-average range: 67–76%).